On this day on 13th November

On this day in 1869 Helene Stöcker, German feminist and peace campaigner, was born. Stöcker studied at the University of Bern, where she became one of the first German women to receive her doctorate. In 1905 she helped found the League for the Protection of Mothers. In 1909, she joined Magnus Hirschfeld in successfully lobbying German parliament from including lesbian women in the law criminalising homosexuality. Stöcker's influential new philosophy, called the New Ethic, advocated the equality of illegitimate children, legalisation of abortion, and sexual education, all in the service of creating deeper relationships between men and women which would eventually achieve women's political and social equality.

During the First World War Stöcker joined the women's pace movement. In February 1915 an international meeting of women met in Amsterdam. Several women that had been involved in the struggle for the vote before the war took part, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Chrystal Macmillan. Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett both accused the women of treason and urged their supporters not to attend.

Over 180 women from Britain were refused permission to travel to the meeting. Even so, fifteen hundred delegates representing Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Britain, Hungary, Italy, Holland, Norway, Sweden and the United States managed to overcome their government's attempt to stop them reaching Amsterdam.

At the meeting the women discussed ways of ending the war. Delegates also spoke about the need to introduce measures that would prevent wars in the future such as international arbitration and the state nationalization of munitions. As a result of the conference a Women's Peace Party was formed. Other women who joined this party included Sylvia Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard, Helena Swanwick, Olive Schreiner, Helen Crawfurd, Al ice Wheeldon, Hettie Wheeldon and Winnie Wheeldon

In 1921 she helped form an organisation with the name Paco and later known as War Resisters' International. She was also very active in the Weimar sexual reform movement. Working for Bund für Mutterschutz, an organisation that sponsored a number of sexual health clinics, which employed both lay and medical personnel, where women and men could go for contraception, marriage advice, and sometimes abortions and sterilisation.

On 31 December 1930 the Pope Pius XI denounced sex without the intent to procreate. Stöcker and the radical sexual reform movement collaborated with the German Social Democratic Party and the German Communist Party to make abortion legal. This campaign came to an end when Adolf Hitler came to power. Stöcker fled first to Switzerland and then to England when the Nazis invaded Austria . Stöcker was attending a PEN writers conference in Sweden when war broke out and remained there until the Nazis invaded Norway, at which point she took the Trans-Siberian Railway to Japan and finally ended up in the United States in 1942. Helene Stöcker died of cancer in 1943.

On this day in 1869 Ariadna Tyrkova, Russian political activist, was born in Novogorod, Russia. She studied in St. Petersburg and married an engineer, and in 1891 gave birth to a son. Ariadna took no interest in politics until her brother was arrested and exiled for being a member of the People's Will. As a schoolgirl she became a close friend of Nadezhda Krupskaya.

Ariadna had wanted to become a doctor but the policies of Alexander III made this an impossibility. She joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party and in 1903 was arrested and charged with smuggling radical newspapers into Russia. She managed to escape and fled to Germany.

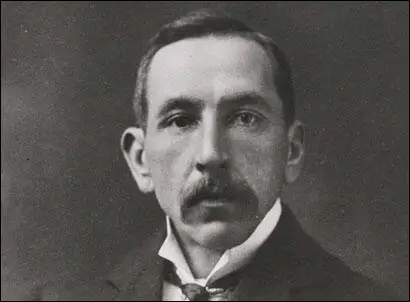

In exile Ariadna lived with Peter Struve and his family in Stuttgart. She returned to Russia after the 1905 Revolution. Ariadna became disillusioned with the various revolutionary groups and helped Paul Milyukov establish the Constitutional Democrat Party (Cadets). Over the next few years she became one of the most important leaders of the Women's Liberation movement in Russia. One wit said that "there was only one real man among the Kadets, and she was a woman." In 1906 she married the English journalist, Harold Williams.

In 1908 she met Nadezhda Krupskaya for the last time in Geneva. She was with her husband, Lenin, who was furious with Tyrkova for abandoning socialism. She told him that she had no desire to live in a Russia ruled by illiterate factory workers. Lenin, smiling coldly, replied that this was why, when the revolution came, she would be amongst the first to hang from a lamp post. Tyrkova said she would never forget the look on his face as he said it.

After the abdication of Nicholas II in March, 1917, she was elected to the Petrograd Duma, where she led the Constitutional Democratic faction. George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown."

On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Kerensky was perhaps the only member of the Government who knew how to deal with the masses, since he instinctively understood the psychology of the mob. Therein lay his power and the main source of his popularity in the streets, in the Soviet, and in the Government."

Ariadna Tyrkova was a candidate in the elections for the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. The Constitutional Democratic Party only won 17 seats. The election was won by the Socialist Revolutionaries. The Bolsheviks were bitterly disappointed with the result as they hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups were banned in Russia.

Ariadna Tyrkova and Harold Williams now fled the country. The following year she published her account of the Russian Revolution in her book, From Liberty to Brest-Litovsk (1918). In 1919 she returned to Russia as a supporter of the White Army in the Russian Civil War. She had now moved to the far-right and had completely rejected the idea of democracy. She wrote: "We must support the army first and place the democratic programs in the background. We must create a ruling class and not a dictatorship of the majority. The universal hegemony of Western democracy is a fraud, which politicians have foisted upon us. We must have the courage to look directly into the eye of the wild beast -- which is called the people."

On this day in 1887 marchers in London protesting about unemployment were badly beaten by police. This event became known as Bloody Sunday. The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) organised a meeting for 13th November, 1887 in Trafalgar Square to protest against the policies of the Conservative Government headed by the Marquess of Salisbury. Sir Charles Warren, the head of the Metropolitan Police wrote to Herbert Matthews, the Home Secretary: "We have in the last month been in greater danger from the disorganized attacks on property by the rough and criminal elements than we have been in London for many years past. The language used by speakers at the various meetings has been more frank and open in recommending the poorer classes to help themselves from the wealth of the affluent." As a result of this letter, the government decided to ban the meeting and the police were given the orders to stop the marchers entering Trafalgar Square.

Henry Hamilton Fyfe was one of the special constables on duty that day: "When the unemployed dockers marched on Trafalgar Square, where meetings were then forbidden, I enrolled myself as a special constable to defend the classes against the masses. The dockers striking for their sixpence an hour were for me the great unwashed of music-hall and pantomime songs. Wearing an armlet and wielding a baton, I paraded and patrolled and felt proud of myself."

The SDF decided to continue with their planned meeting with Henry M. Hyndman, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham being the three main speakers. Edward Carpenter explained what happened next: "The three leading members of the SDF - Hyndman, Burns and Cunninghame Graham - agreed to march up arm-in-arm and force their way if possible into the charmed circle. Somehow Hyndman was lost in the crowd on the way to the battle, but Graham and Burns pushed their way through, challenged the forces of Law and Order, came to blows, and were duly mauled by the police, arrested, and locked up. I was in the Square at the time. The crowd was a most good-humoured, easy going, smiling crowd; but presently it was transformed. A regiment of mounted police came cantering up. The order had gone forth that we were to be kept moving. To keep a crowd moving is I believe a technical term for the process of riding roughshod in all directions, scattering, frightening and batoning the people."

Walter Crane was one of those who witnessed this attack: "I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again."

The Times took a different view of this event: "It was no enthusiasm for free speech, no reasoned belief in the innocence of Mr O'Brien, no serious conviction of any kind, and no honest purpose that animated these howling toughs. It was simple love of disorder, hope of plunder it may be hoped that the magistrates will not fail to pass exemplary sentences upon those now in custody who have laboured to the best of their ability to convert an English Sunday into a carnival of blood."

George Barnes was one of those who was badly injured by the charging police horses. Some of the protesters were arrested and later two of the leaders of the march, John Burns and Robert Cunninghame Graham, were arrested and later sentenced to a six-week prison sentence.

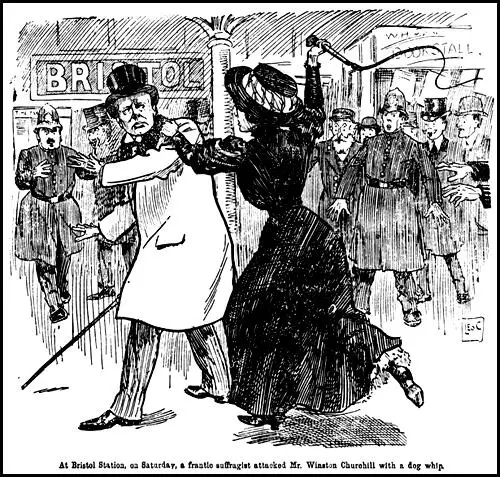

On this day in 1909 Theresa Garnett accosted Winston Churchill with a whip at Bristol Station. She shouted "take that you brute", however, she later admitted she missed him. She was arrested for assault but was found guilty of disturbing the peace and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Horfield Prison. Her friend, Mary Blathwayt, wrote in her diary on 15th November: "Miss Garnett got one month for whipping Mr. Churchill across the face and not hurting him. I bought fruit and sent it to the prisoners before they were taken away."

The following day, her mother, Emily Blathwayt, wrote: The papers were full of Saint Theresa as we call her." Emily went onto say that the movement was "not altogether displeased" that the newspapers had headlines that were not true such as "Winston whipped" and "Churchill flogged". Emily added that her husband Colonel Linley Blathwayt had "sent her photo which he had taken by Mary who gave it to her before she went off to prison."

Theresa Garnett went on hunger-strike while in Horfield Prison. This time, instead of being released, she was forcibly fed. As a protest against this treatment, she set fire to her cell and was then placed in solitary confinement for 11 of the 15 remaining days of her sentence. After being found unconcious, she spent the rest of her sentence in a hospital ward.

In 1910 Garnett became WSPU organizer in Camberwell. However, she disagreed with the WSPU arson campaign and left the movement. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) she "did not join any other suffrage group, although she obviously kept in touch with her erstwhile comrades."

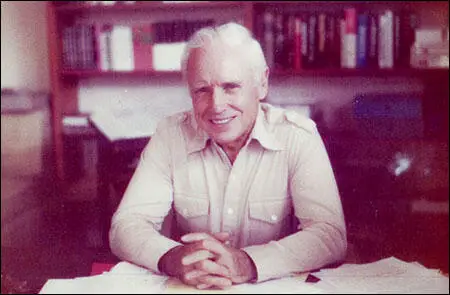

On this day in 1910 William Bradford Huie, campaigning journalist was born in Hartselle, Alabama. Educated at the University of Alabama, first novel, Mud on the Stars (1942) dealt with the Depression in the Deep South. He followed this with the best-selling The Revolt of Mamie Stover (1951).

Huie became involved in the campaign for black civil rights and wrote about the activities of Asa Earl Carter and the Ku Klux Klan for national magazines such as Time. This included cases such as the castration of Edward Aaron and the lynching of Emmett Till. Articles about the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, were later published as a book, Three Lives For Mississippi (1964).

Other books by Huie included The Execution of Private Slovik (1954), The Klansman (1967) and He Slew the Dreamer (1970), an investigation into the assassination of Martin Luther King. Bradford published 21 books and they have sold over 28 million copies. William Bradford Huie died in 1986.

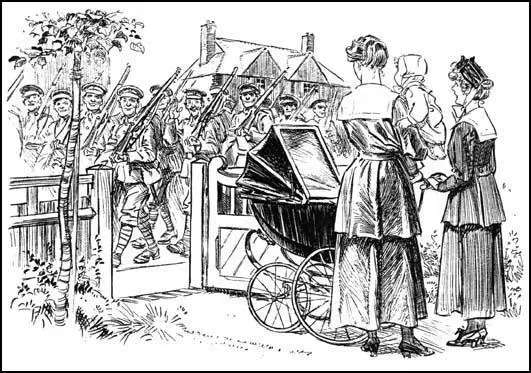

On this day in 1915 a letter is published in The East Grinstead Observer complaining about "women's patrols". In the First World War it was decided to billet the soldiers in local towns and villages. Some people became concerned about the soldiers corrupting local girls. The Headmistresses' Association and the Federation of University Women suggested the formation of Woman's Patrols to stop local woman from becoming too friendly with the soldiers.

The War Office gave permission for these patrols to take place outside military camps. They were also very active in public parks and cinemas. After visiting 300 cinemas in three weeks, the Women's Patrol Committee recommended that lights were not dimmed between films. Women's Patrols worked closely with the local police and the Women Police Volunteers. It is estimated that during the First World War over 2,000 patrols were established, including over 400 in London.

It created great controversy in the town of East Grinstead. In an unsigned letter published in the newspaper on 13th November, 1915, a young woman wrote: "Something must be done to stop these so-called 'Ladies' from interfering with respectable girls and their friends. I'm not ashamed to admit that I made friends with several soldiers and I have found them to be perfect gentlemen. On two or three occasions one or two of these ladies spoke to me about the behaviour of the girls and soldiers in the town. These women seem to know all the girls in East Grinstead and Forest Row and all their business. They mentioned several things that I had done. They seem to know the exact place and time so I suppose they were watching me. I trust they will soon find something more useful to occupy their time."

Another unsigned letter said: "It is about time something was done about ancient spinsters following soldiers about with their flash lights. I have seen a great deal of the soldiers who have been here and I consider that they have have been unfairly treated. Walking in the roads and fields accompanied by friends is no crime. What would these spinsters think if soldiers flashed a light upon them in their gardens or darkened drawing rooms?"

Helena Swanwick later defended the behaviour of young women during the war. "Sex before marriage was the natural female complement to the male frenzy of killing. If millions of men were to be killed in early manhood, or even boyhood, it behoved every young woman to secure a mate and replenish the population while there was yet time."

Nursemaid: (unguardedly): "I don't know yet, Ma'am.

On this day in 1916 Prime Minister of Australia, William Hughes is expelled from the Labor Party over his support for conscription. Andrew Fisher found the strain of being prime minister during the First World War exhausting and in 1915 he resigned. Hughes now became head of the government. Hughes was a strong supporter of Australia's participation in the war and General William Birdwood managed to persuade him that conscription was necessary. However, the vast majority of members of the Labor Party were opposed to the measure.

Hughes argued in a speech in December, 1915: "We must put forth all our strength. The more Australia sends to the front the less the danger will be to each man. Not only victory, but safety belongs to the big battalions. Australia turns to you for help. Fifty thousand additional troops are to be raised to form the new units of the expeditionary forces. Sixteen thousand men are required each month for reinforcements at the front. This Australia of ours, the freest and best country on God's earth, calls to her sons for aid. Destiny has given to you a great opportunity. Now is the hour when you can strike a blow on her behalf. If you love your country, if you love freedom, then take your place alongside your fellow-Australians at the front, and help them to achieve a speedy and glorious victory."

On this day in 1956 the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. In the 1950s the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was involved in the struggle to end segregation on buses and trains. In 1952 segregation on inter-state railways was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This was followed in 1954 by a similar judgment concerning interstate buses. However, states in the Deep South continued their own policy of transport segregation. This usually involved whites sitting in the front and blacks sitting nearest to the front had to give up their seats to any whites that were standing.

African American people who disobeyed the state's transport segregation policies were arrested and fined. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant from Montgomery, Alabama, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man.

After her arrest, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, helped organize protests against bus segregation. He was joined by other campaigners for civil rights, including Ralph David Abernathy, Edgar Nixon and Bayard Rustin. The group was persuaded by JoAnn Robinson, of the Women's Political Council, that they should launch a bus boycott. The idea being that the black people in Montgomery should refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court on 13th November, 1956, forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. The following month the buses in Montgomery were desegregated.