Mississippi Burning

In 1964 the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) organised its Freedom Summer campaign. Its main objective was to try an end the political disenfranchisement of African Americans in the Deep South. Volunteers from the three organizations decided to concentrate its efforts in Mississippi. In 1962 only 6.7 per cent of African Americans in the state were registered to vote, the lowest percentage in the country.

CORE, SNCC and NAACP also established 30 Freedom Schools in towns throughout Mississippi. Volunteers taught in the schools and the curriculum now included black history, the philosophy of the civil rights movement. During the summer of 1964 over 3,000 students attended these schools and the experiment provided a model for future educational programs such as Head Start.

Freedom Schools were often targets of white mobs. So also were the homes of local African Americans involved in the campaign. That summer 30 black homes and 37 black churches were firebombed.

On 21st June, 1964 James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, went to Longdale to visit Mt. Zion Methodist Church, a building that had been fire-bombed by the Ku Klux Klan because it was going to be used as a Freedom School.

On the way back to the CORE office in Meridian, the three men were arrested by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price. Later that evening they were released from the Neshoba jail only to be stopped again on a rural road where a white mob shot them dead and buried them in a earthen dam.

When Attorney General Robert Kennedy heard that the men were missing, he arranged for Joseph Sullivan of the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) to go to Mississippi to discover what has happened. On 4th August, 1964, FBI agents found the bodies in an earthen dam at Old Jolly Farm.

On 13th October, Ku Klux Klan member, James Jordon, confessed to FBI agents that he witnessed the murders and agreed to co-operate with the investigation. Aware that it would be impossible to persuade a white Mississippi jury to convict the murderers, the government decided to arrange for nineteen of the men to be charged under an 1870 federal law of conspiring to deprive Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney of their civil rights. This included Sheriff Lawrence Rainey and Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price.

On 24th February, 1967, Judge William Cox dismissed seventeen of the nineteen indictments. However, the Supreme Court overruled him and the Mississippi Burning Trial started on 11th October, 1967. The main evidence against the defendants came from James Jordon, who had taken part in the killings. Another man, Horace Barnette had also confessed to the crime but refused to give evidence at the trial.

Jordan claimed that Price had released Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney at 10.25. but re-arrested them before they were able to cross the border into Lauderdale County. Price then took them to to the deserted Rock Cut Road where he handed them over to the Ku Klux Klan.

On 21st October, 1967, seven of the men were found guilty of conspiring to deprive Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney of their civil rights and sentenced to prison terms ranging from three to ten years. This included James Jordon (4 years) and Cecil Price (6 years) but Sheriff Lawrence Rainey was acquitted.

Civil Rights activists led by Ruth Schwerner-Berner, the former wife of Michael Schwerner and Ben Chaney, the brother of James Chaney, continued to campaign for the men to be charged with murder. Eventually, it was decided to charge Edgar Ray Killen, a Ku Klux Klan member and part-time preacher, with more serious offences related to this case. On June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the crime, Killen was found guilty of the manslaughter of the three men.

Primary Sources

(1) Erskine Caldwell, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

Mississippi: The white farmer has not always been the lazy, slipshod, good-for-nothing person that he is frequently described as being. Somewhere in his span of life he became frustrated. He felt defeated. He felt the despair and dejection that comes from defeat. He was made aware of the limitations of life imposed upon those unfortunate enough to be made slaves of sharecropping. Out of his predicament grew desperation, out of desperation grew resentment. His bitterness was a taste his tongue would always know.

In a land that has long been glorified in the supremacy of the white race, he directed his resentment against the black man. His normal instincts became perverted. He became wasteful and careless. He became bestial. He released his pent-up emotions by lynching the black man in order to witness the mental and physical suffering of another human being. He became cruel and inhuman in everyday life as his resentment and bitterness increased. He released his energy from day to day by beating mules and dogs, by whipping and kicking an animal into insensibility or to death. When his own suffering was more than he could stand, he could live only by witnessing the suffering of others.

(2) Jonathan Steele, Summer of Hate, The Guardian (18th June, 1964)

The voice on the line was polite but insistent. The FBI was conducting a nationwide manhunt for three men who had disappeared in Mississippi. My car had been found abandoned in suspicious circumstances in nearby Louisiana. Would I come immediately to explain why, and whether I knew anything about the men?

The phone call was unnerving even though I had nothing to hide, and I hastened to obey the summons. Of course I knew that the men had gone missing: the case was rocking America that summer, exactly 40 years ago. America's turbulent civil rights decade was at its height and the missing men were three volunteer activists who had been helping black people stand up for their rights and register to vote in the Deep South's most violent state. They had been arrested by the deputy sheriff of Neshoba county on June 21, held for a few hours, and released after dark. Two days later their burned-out station wagon was discovered on a lonely road, but the men were nowhere to be found.

James Chaney, 21, was a black Mississippian from Meridian, a city in the eastern part of the state. Micky Schwerner, 24, was a Jewish activist from New York City who had spent four months in Meridian, running various civil rights projects. Andrew Goodman, 20, came from an upper-middle-class New York family, and had arrived in Mississippi only the day before he went missing. Their terrible story was later turned into a film, Mississippi Burning.

The three activists had disappeared a few hours after a cavalcade of 200 young people arrived in Mississippi for what was called the Freedom Summer. The term "human shields" was not yet in vogue but that is what we were. The idea was that as outsiders we might shame Mississippi's police and sheriffs into reducing their brutality. With the exception of a handful of foreigners such as myself, the roughly 800 volunteers were American - mostly students from prestigious Ivy League universities and other private colleges. We had to bring $500 for use as bail money in the very probable case of being arrested on trumped-up or minor charges.

There were a few middle-class blacks but the majority were affluent whites, and firm believers in the American dream. In the deep south they were vilified as "outside agitators", as though they had no business to be there. They discovered another America, a society in which they were indeed foreigners. Here was a state where blacks made up 45% of the population but only 6% had managed to overcome the poll taxes, the unfairly administered literacy tests and violent reprisals, just to get on the register to exercise their American right to vote.

(3) Rita Schwerner, interviewed by William Bradford Huie for his book Three Lives for Mississippi (1964)

There was nothing masochistic about Mickey Schwerner. He wanted to live: he loved life. He didn't want to die. He was a capable of fear as any young man. I have seen him afraid. It's true that he didn't fear a few days in jail. And he had no great fear of being slapped, kicked, or beaten. But to save his life, I think he would have done anything within his physical power. Mickey was incapable of believing that a police officer in the United States would arrest him on a highway for the purpose of murdering him, then and there, in the dark.

(4) James Jordon, cross-examined at the Mississippi Burning Trial (October, 1967)

Question: Then what happened?

Answer: About that time the Deputy's car came by, said something to the man in the red car, and the Deputy's car, and we took off to follow them.

Question: What deputy are you talking about?

Answer: Cecil Price.

Question: Then what did you do?

Answer: Turned the cars around come back toward highway 19.

Question: Then where did you go?

Answer: Turned left on highway 19 all the way to, oh about 34 miles to this other cut-off road which wasn't a paved highway and then they said somebody had better stay here and watch in case anything happens, 'til the other car comes.

Question: How about the people, uhh, did you pass the red car going?

Answer: Yes sir.

Question: You were going toward Philadelphia?

Answer: Yes sir.

Question: And was anyone in the red car when you passed it?

Answer: This young man and Sharpe were still there.

Question: Now, did any of these people, uhh did they both stay there?

Answer: No sir, Sharpe got in the, I believe he got in the wagon or the other car that was ahead of us, I don't know where he got in the police car or not.

Question: Will you tell the Court and Jury what you heard and what you did?

Answer: Well, I hear a car door slamming, and some loud talking, I couldn't understand or distinguish anybody's voice or anything, and then I heard several shots.

Question: Then what did you do?

Answer: Walked up the road toward where the noise came from.

Question: And what did you see when you walked up the road?

Answer: Just a bunch of men milling and standing around that had been in the two cars ahead of us and someone said, "better pick up these shells." I hollered, "what do you want me to do?"

Question: Then what did you do?

Answer: Then...

Question: Excuse me, did you see these three boys?

Answer: Yes sir, beside the road.

Question: How were they?

Answer: They were lying down.

Question: Were they dead?

Answer: I presume so, yes sir.

(5) H. C. Wilkins, defence lawyer, Mississippi Burning Trial (October, 1967)

Now, what's the theory of the Government's case? Actually isn't it a theory of this case that here in Mississippi, that there is so much hate and prejudice in Mississippi that we hate all outsiders, and that there is a group of people here in Mississippi so filled with that hate that they conspire together and meet together organize organizations to do away and murder outsiders that come into this State.

Members of the Jury, I know you know what an old scapegoat is. It's nothing but just a billy goat with a bell on it, and they used to bring all of the other innocent animals into the slaughtering house, or the slaughtering pen, and when they get there and they go on with their slaughtering, and that's exactly what Jim Jordan is. But the most miraculous thing about that, I knew the government used that before, they have in years gone by, and all the times I've been engaged in the practice of law I never knew a State of a Government in the presentation of their case to try to blow hot and cold in the same breath. They got in here and they put Jim Jordan on the stand and he sat up there with his eyes all bugged out and he just rattles it off like that, just exactly what happened, he said. Then, the government, just a little bit later, brings statement and say you ought to convict somebody on which impeaches almost everything he said. I just don't see how the government can have so many theories of these cases and then represent to you there's no reasonable doubts, there's no mistake.

(6) Kenneth Fairly and Harold Martin, The Saturday Evening Post (October, 1967)

Deep angers and frustrations now motivate the Klansman. He is rebelling against his own ignorance, ignorance that restricts him to the hard and poorly paid jobs that are becoming scarcer every day. He is angered by the knowledge that the world is passing him by, that he is sinking lower and lower in the social order. The Negro is his scapegoat, for he knows that so long as the Negro can be kept "in his place," there will be somebody on the social and economic scale who is lower than be. In the Klavern in his robes, repeating the ancient ritual, he finds the status that is denied him on the outside.

(7) Stanley Kauffman, review of the film, Mississippi Burning, The New Republic (9th January, 1989)

Docudrama is a dubious genre; something that pretends to be docudrama is even more dubious. Mississippi Burning was patently based on the murder of three civil rights workers in June 1964 - a local black, James Chaney, and two white Northerners, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. Admittedly it would be difficult to make a film on that subject and keep it more document than invention, but this film doesn't try very hard. It wants praise for facing facts fearlessly without being bound by them. A few lines, tucked in at the very end after the long closing list of credits, tell us that Mississippi Burning is not factual, that it was only suggested by the facts. This strategy licensed the filmmakers - Chris Gerolmo, the writer, Alan Parker, the director, Frederick Zollo and Robert F. Colesberry, the producers-to lard the story with movie stuff in order to make it "play".

The biggest surprise in the film is that the states of Mississippi and Alabama cooperated in the making of Mississippi Burning of course the production put money in the pockets of residents in the area-many of them are seen in the film-but I doubt that this would have been decisive 24 years ago. Perhaps the clearest sign of progress in race relations down there is that the location shooting was done where it was.

(8) Les Bayless, People's Weekly World (25 May, 1996)

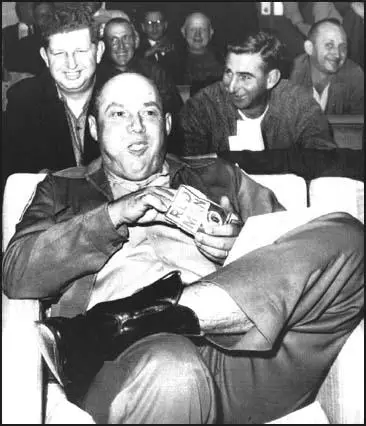

Buford Posey was stunned when he picked up the March 13 copy of the Neshoba Democrat, a local newspaper. Prominently featured was a photo of the newly sworn-in officers of the Neshoba County Shriners club. Among the men in the photo was Cecil Price who had just taken the oath as the Shriners' vice president.

"Cecil Price was the chief deputy sheriff of Neshoba County in 1964," Posey told the People's Weekly World in an exclusive interview. "He led the Ku Klux Klan that lynched Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman on Sunday night, June 21, 1964.I have tried without success to get Mississippi newspapers to comment on this outrage of Cecil Price being elected as a high-ranking Masonic leader," Posey said.

Although Posey comes from a prominent Mississippi family, he was active in the civil rights movement in the early '60s. He will tell you, with not a little bit of pride in his voice, that he was the first white person in Mississippi to join the NAACP. He now lives in Oxford, where he receives a small disability pension.

Posey said that the FBI knew who murdered the civil rights workers within hours of the grisly event. "In those days I was in Neshoba County, where I was born and raised. Though I traveled around a lot, I had been at my father's in Philadelphia because he was dying of prostate cancer," Posey said.

"The murders took place on a Sunday night, June 21, 1964 on Rock Cut Road, right off Highway 19. I was sitting home that night. It was late, 2 o'clock or something like that, and I received a call. I recognized the voice at once." The caller was Edgar Ray Killen, the "chaplain" of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. "We took care of your three friends tonight and you're next," Killen told Posey.

Posey had gone to Meridian the week before and talked to Schwerner, the oldest of the three murdered workers. "I told them to be careful. 'The Klan has sentenced you to death. You know the sheriffs up there, Lawrence Rainey and Cecil Ray Price, are Klan members.'"

The morning after the call from Killen, Posey contacted the FBI, first in Jackson and then New Orleans. "I told them I was a civil rights worker, who I worked for and what had happened. I told them the preachers' name and that I thought the sheriff's office was involved in the murder."

Though the FBI ignored Posey, a chain of events was soon set in motion that led to the discovery of the bodies and another three years later, the conviction of Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, Price and five others on federal charges of violating the civil rights of the three murdered men.

Posey had talked to newspaper columnist Drew Pearson who was a friend of President Lyndon Johnson. Johnson and the "big news organizations," according to Posey, started to put the pressure on.

Mississippi never brought state charges against any of the Klansmen who committed these crimes. Posey thinks there's a reason for that. "When I was coming up most of the white people in Mississippi didn't know it was against the law to murder a Black person," he said. He recalled an incident he witnessed as a child that shaped his thinking on the genocidal cruelty of racism.

"I was in Philadelphia one Saturday afternoon - in the olden days people came to town on Saturday - they were share croppers and the like. Well, to make a long story short, there was this Black teenager. There was this white woman who came out of a store right there on Court Square." The teen accidentally bumped into her. The woman started screaming.

"Well, some men went into Johnson's hardware store and took out some shotguns," Posey said. "They chased the poor young fellow around Court Square, shooting at him. They killed him and chained him to the flag pole."

In 1994 hundreds of veteran civil rights workers gathered in Jackson to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Freedom Summer. Among those attending the conference were Rita Schwerner, widow of Michael Schwerner, and Carolyn Goodman, mother of Andrew Goodman.

A political firestorm was set off when Dick Molphus, then a Democratic candidate for governor, apologized to Carolyn Goodman. Gov. Kirk Fordice rebuked Molphus, saying it did no good to drag up the past. Posey believes this provided the incentive for Neshoba County to "rehabilitate" Cecil Price.

The rededication of the grave site of James Chaney in nearby Meridian was the emotional highlight of the Mississippi homecoming. Chaney's brother, Ben, had a warning for civil rights veterans who had come to honor the three martyrs.

"There are a lot of good people in Mississippi," he said. "But there are still some who haven't learned the lessons of the past. There are still people in Mississippi who don't want my brother to rest in peace."

Chaney told the World that gunshots from a high-powered rifle had been fired into his brother's gravestone. At least one attempt had been made to dig up and steal the body.

Rev. Charles Johnson, who was a government witness in the federal trial of Chaney's murderers, sounded a more optimistic note. "These three men shed their blood in the state of Mississippi and because of them we have the Voting Rights Act. Because of them we have more elected Black officials in Mississippi than in any other state."

Johnson said, "In this state, hatred flowed like a river. Where hatred rolled, freedom and love now flow. We have to get to the young people and let them know what Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman did for them."

(9) Patsy R. Brumfield, Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal (21st June, 2005)

It was 41 years ago today that Mickey Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and Michael Chaney headed to Philadelphia to help some local blacks who had been beaten by the Klan and whose church had been burned. Today, we know that they were lured here to die....

When we had left here Monday night, we were a bit apprehensive that Killen would be acquitted. The jury’s forewoman had announced a 6-6 split. There’s no way to know yet, but on reflection today, it could have been 6 guilty for murder and 6 guilty for manslaughter. That makes more sense in the light of today’s pronouncements.

So, there I sat in the courtroom. Mickey Schwerner’s widow Rita Bender was within my sight as she waited anxiously on the front row on the left side of the courtroom. Killen’s family looked concerned on the right side.

Security was extensive around and within the Neshoba County courthouse. I saw men with rifles entering about 7 a.m. and the entire Philadelphia Swat team assembled nearby. Dozens of Highway Patrolmen were stationed at the doorways and within the courtroom. Just before the sentence was pronounced, the most muscular of the patrolmen came forward in the aisles to discourage any members of the public from doing anything inappropriate upon hearing Killen’s fate.

The jury was escorted in and lined up in a semicircle in front of the judge’s bench. Gordon asked if they had reached a verdict. They had, said the forewoman. Hand me the verdicts, Gordon said, then he read each carefully. He polled each one to determine if these verdicts were their own. Yes, each said. Then clerk Lee read the verdicts: guilty of manslaughter, guilty of manslaughter and guilty of manslaughter.

A collective sigh came from many onlookers, who had been admonished to behave when the verdicts were read. “The court appreciates your attention and services,” Gordon said to jurors just before they were dismissed and escorted to their vehicles. No one else moved or could move in the courtroom.

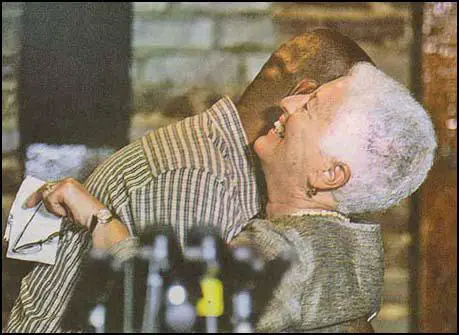

Killen’s white-haired wife rose from her seat near the front row and put her arms around him as he sat impassively in his wheelchair. At 11:26, Gordon said, “Edgar Ray Killen, a jury has found you guilty.” The judge committed him to the custody of the sheriff and Killen was wheeled from the courtroom. As Mrs. Killen sat back in her seat, the people on each side of her embraced her and each put an arm around her quavering shoulders...

After the verdict, the Media Center hosted a massive news conference, live on CNN and other media outlets. First to the microphone was Rita Schwerner Bender, then Ben Chaney, younger brother of James Chaney. I wish I could tell you exactly what they said, but I was busy trying to make sure things were moving along technically. When they completed lengthy remarks and thanks, they were followed by Attorney General Jim Hood of Houston and local District Attorney Mark Duncan. Hood and Duncan spent a lot of time at the mic talking about the trial, how difficult its preparation had been and about information they had that never got into testimony. Duncan would not say if any others could be tried in this crime.

Also making remarks were members of the Philadelphia Coalition, a local group of whites and blacks who had pressed hard for Killen’s indictment. Their faces told the story of how proud they felt of the trial’s conclusion.

I’m seeking to wind down the Media Center in hopes of getting back to the job I signed on for almost two years ago – at the Daily Journal. Thanks to Lloyd Gray and Mike Tonos for allowing me to do this. It has been an unforgettable experience I got to share with my son, a Meridian reporter headed for Ole Miss law school this fall. We’ll always be able to share this. It was a moment, but it was an important one because hopefully it has lifted the stigma of “Mississippi Burning” from our good state.

(10) Budd Mishkin, New York 1 News (21st June, 2005)

A Mississippi jury convicted former Ku Klux Klan leader Edgar Ray Killen of manslaughter Tuesday, 41 years after the murder of three civil rights workers, including two from New York City.

The jury of nine whites and three blacks reached the verdict on their second day of deliberations, rejecting murder charges against the 80-year-old defendant.

Killen sat motionless as the verdict was read and was later comforted by his wife as he sat in his wheelchair, attached to an oxygen tube.

Civil rights workers James Chaney and New Yorkers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were ambushed on June 21, 1964. Their bodies were found 44 days later. They had been beaten and shot.

Here in New York, Goodman's mother told NY1 the verdict is one she has been waiting for ever since her son was killed.

"This is something I was hoping would happen," said Carolyn Goodman in a statement. "I have waited 40 years for this. I hope this man will pay for his crimes and know what he did."

Killen, who was a part-time preacher and sawmill operator, was tried in 1967 on federal charges of violating the victims' civil rights. But the all-white jury deadlocked, with one juror saying she could not convict a preacher.

Seven others were convicted, but none served more than six years.

Killen was indicted on murder charges this time around, which could have carried a life sentence, but the defense appealed to the jury to lessen the conviction to manslaughter charges. Killen now faces a maximum of 20 years in prison on each of the three counts.

The conviction comes exactly 41 years to the day after the three civil rights workers disappeared.

(11) Jamie Wilson, Klan Member Guilty of 1964 killings, The Guardian (22nd June, 2005)

Exactly 41 years to the day after three young civil rights activists disappeared in Mississippi, Edgar Ray Killen, a Ku Klux Klan member and part-time preacher, yesterday became the first person convicted over their killing. The jury found the 80-year-old guilty of manslaughter in the deaths of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who were ambushed, beaten, and shot while working to promote black voting rights during the "freedom summer" of 1964. Although the jury rejected the more serious murder charges against the former Klan leader, Killen could still face 20 years in prison for his part in the killings, which inspired the 1988 film Mississippi Burning. He will be sentenced tomorrow, Killen, wearing an oxygen mask and in a wheelchair since breaking both legs during a logging accident, showed no emotion as the verdict was read out. Schwerner's widow, Rita Schwerner Bender, welcomed the verdict, calling it "a day of great importance to all of us". But she said others also should be held responsible for the murders. "Preacher Killen didn't act in a vacuum," she said. There are believed to be seven more men involved who are still alive. The three victims - Chaney, a black activist from Mississippi, and Schwerner and Goodman, white activists from New York - were picked up by a local policeman after they visited the ruins of a black church burned down by the Klan the previous week. The men were released in the middle of the night, but the policeman, a Klan member, had tipped off local Klansmen and they were chased down in their car by a mob, who shot and then buried them. Their bodies were found 44 days later. In 1967, 18 men, including Killen, were tried on conspiracy charges. Seven were convicted, but none served more than six years in prison. Killen walked free as a result of a hung jury.

(12) Gary Younge, Mississippi Wins its Long Race for Justice, The Guardian (22nd June, 2005)

The conviction of Edgar Ray Killen for the manslaughter of three civil rights workers has a symbolic significance that goes beyond the families of those who died 41 years ago.

At stake was not just how Killen would spend his fading years, but whether Mississippi - a state Martin Luther King described as "sweltering in injustice" in his "I have a dream" speech - could, and should, address its segregationist past...

Mark Duncan, the prosecuting district attorney countered: "There is only one question. Is a Neshoba county jury going to tell the rest of the world that we are not going to let Edgar Ray Killen get away with murder anymore? Not one day more."

Most of the evidence presented at the trial has been known for 40 years. "It wasn't like there was any one thing that happened that said, 'Here's the magic bullet'," Mr. Duncan told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. "It really was that we had gotten to the end. There was nothing to do."

But as the defendants and the witnesses got older, there was a fear that Killen might die and take Mississippi's reputation down with him. For some this was a race against time to show that the potency of race in the former Confederacy had been extinguished.

Killen's manslaughter conviction, like the conviction of 22 others for civil rights-era killings in the past 16 years, was part of a push to show that the goods, as well as the packaging, had changed...

According to a census report from 2002, the top five residentially segregated metropolitan areas in the US are Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, St Louis and Newark - none of which is in the south. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, you will find higher rates of black poverty in the northern states of Wisconsin, Illinois and West Virginia than in Mississippi.

The only difference between the north and the south, wrote the late James Baldwin, was that "the north promised more. And (there was only) this similarity: what it promised it did not give and what it gave, at length and grudgingly with one hand, it took back with the other."

Nonetheless, if much has changed, much has remained the same. Indeed the Klan still march in town every year, and during the trial Harlan Majure, the mayor of Philadelphia during the 1990s, said he had no problem with the Ku Klux Klan. Mr Majure told the jury the Klan "did a lot of good up here", and claimed that he was not personally aware of the organisation's bloody past.

African Americans in the state remain at a huge disadvantage. Infant mortality rates are twice as high, earnings are half as much as whites, and black people are three times as likely to live in poverty. The state has the lowest wages and highest infant mortality rates and poverty in the country....

And last night Ben Chaney, the brother of one of the victims, James Chaney, a black Mississippian, thanked "the white people who walked up to me and said things are changing. I think there's hope."

In the 40 years since he killed the three young civil rights workers, Edgar Ray Killen has remained unrepentant. He told the New York Times six years ago the ex-Klansman branded his victims "communists" who were threatening Mississippi's way of life. "I'm sorry they got themselves killed" was all the remorse he could muster. That way of life denied black people the vote, kept races separate and unequal and that's how he liked it.

Both reclusive and notorious, he ran a sawmill and lived with his wife in a small house with a tablet displaying the Ten Commandments on his lawn. Until the trial opened last week he denied he had any involvement in the Klan, although those in the town said his involvement was always an open secret. "Killen was one of those rednecks," says 89-year-old Buford Posey. "I know ... I was one of those rednecks." Investigators always insisted he was the leader of the mob that night.

Howard Ball, a civil rights worker who wrote Murder in Mississippi: United States v. Price and the Struggle for Civil Rights, described the preacher as "the mastermind". "He got the gloves, he got the backhoe operator, he was able to work with (a local landowner) to get the site of the burial," Ball told the Los Angeles Times. "If there is one person, it should be him."