On this day on 12th January

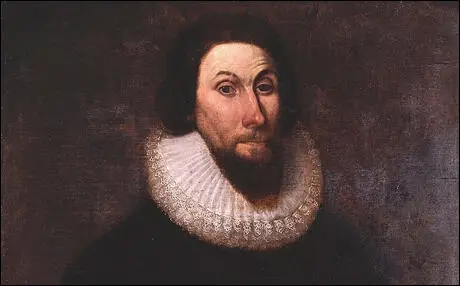

On this day in 1588 John Winthrop, was born in Groton, Suffolk, England. Educated at Cambridge University he practised law in London but was persecuted for his Puritan religious beliefs. Winthrop thought that the Church of England should abolish bishops, ecclesiastical courts and other relics of Roman Catholicism such as kneeling and the use of priestly vestment and altars. The Separatists also believed that the government was too tolerant towards those who were guilty of adultery, drunkenness and breaching the Sabbath.

Winthrop was granted a charter for the Massachusetts Bay Colony and arrived with 700 settlers in 1630. He served as governor of Massachusetts for 12 terms and was considered to be a good leader. However in 1636 he clashed with Roger Williams and was forced to banish from the colony.

One of the settlers, Anne Hutchinson, began to claim that good conduct could be a sign of salvation and affirmed that the Holy Spirit in the hearts of true believers relieved them of responsibility to obey the laws of God. She also criticised New England ministers for deluding their congregations into the false assumption that good deeds would get them into heaven. Complaints were made about Hutchinson's teachings and Winthrop eventually expelled her from the colony.

In 1645 Winthrop became the first president of the Confederation of New England. Winthrop's History of New England was published after his death in 1649.

On this day in 1856 artist John Singer Sargent, the eldest surviving child of American parents, Dr Fitzwilliam Sargent (1820–1889) and his wife, Mary Newbold Singer (1826–1906), was born in Florence on 12th January, 1856. His mother came from a very wealthy family in Philadelphia.

He studied painting in Italy and France and in 1884 caused a sensation at the Paris Salon with his painting of of a young socialite named Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. Exhibited as Madame X, people complained that the painting was provocatively erotic.

His biographers, Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond, have argued: "Its largely hostile reception was one factor spurring his decision to leave Paris for London. Sargent had already been asked to paint members of the Vickers family (connected with the famous armaments firm) in England" Over the next few years he established himself as the country's leading portrait painter. This included portraits of Joseph Chamberlain (1896), Frank Swettenham (1904) and Henry James (1913). Sargent made several visits to the USA where as well as portraits he worked on a series of decorative paintings for public buildings such as the Boston Public Library (1890).

In London he became friends with Henry Tonks and William Rothenstein. He possessed a huge appetite and became corpulent in middle age. Rothenstein pointed out in Men and Memories (1932) that he used to visit "the Hans Crescent Hotel, where, from the table d'hôte luncheon of several courses, he could assuage his Gargantuan appetite".

John Singer Sargent became the most important portrait painter of the period and demand very high prices for his work. He received £2,100 for The Ladies Alexandra, Mary, and Theo Acheson (1902), £3,000 for his group of medical doctors Professors Welch, Halsted, Osler and Kelly (1906)and £2,500 for his painting of the Marlborough family.

Sargent spent most of the First World War in the United States. In 1918 Sargent was commissioned to paint a large painting to symbolize the co-operation between British and American forces during the war. Sargent was sent to France with Henry Tonks. One day Sargent visited a casualty clearing station at Le Bac-de-Sud. While at the casualty station he witnessed an orderly leading a group of soldiers that had been blinded by mustard gas. He used this as a subject for a naturalist allegorical frieze depicting a line of young men with their eyes bandaged. Gassed soon became one of the most memorably haunting images of the war. While in France Sargent also painted The Interior of a Hospital Tent (1918) and A Street in Arras (1918).

It has been claimed by Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond: "The impression that emerges from descriptions by his sitters is of a vigorous, decisive, and driven artist. There are stories of Sargent's rushing to and from the easel, totally absorbed, placing his brushstrokes in gestures of absolute precision, of the cries of frustration as he rubbed out, scraped down, reworked, and grappled with the problems of representation, cries punctuated by his mild expletives... Occasionally, he would dash to the piano and play as a brief respite from painting. He was single-minded about what he wanted to achieve and would brook no interference - an approach born of professional self-belief rather than personal arrogance, from which he was remarkably free. He insisted on the right to select his sitters' costumes and accessories, and took brisk exception to comments from his sitters and their families about the truth of the likenesses and characterizations he created."

Cynthia Asquith claims that he was a "curiously inarticulate man, he used to splutter and gasp, almost growl with the strain of trying to express himself; and sometimes, like Macbeth at the dagger, he would literally clutch at the air in frustrated efforts to find, with many intermediary ‘ers’ and ‘ums’, the most ordinary words." Vernon Lee, a very close friend, added: "He was very shy, having I suppose a vague sense that there were poets about… I think John is singularly unprejudiced, almost too amiably candid in his judgements… He talked art & literature, just as formerly, and then, quite unbidden, sat down to the piano and played all sorts of bits of things."

Evan Charteris, the author of John Sargent (1927), has written: "He read no newspapers; he had the sketchiest knowledge of current movements outside art; his receptive credulity made him accept fabulous items of information without question. He would have been puzzled to answer if he were asked how nine-tenths of the population lived, he would have been dumbfounded if asked how they were governed."

John Singer Sargent died in his sleep on 15th April 1925 at home in Tite Street having suffered a heart attack. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, on 18th April.

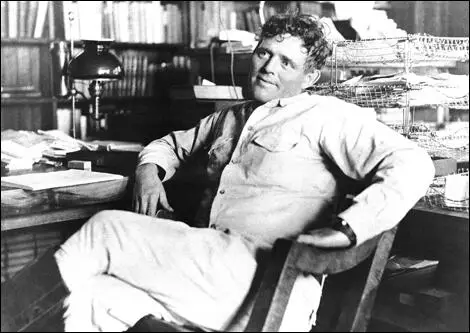

On this day in 1876 novelist and social reformer, Jack London was born in San Francisco. London had a great love of books and spent a lot of time in Oakland Library. His reading included books by Rudyard Kipling, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy and Herman Melville. London also began writing short-stories. When the San Francisco Morning Call announced a competition for young writers, the 17 year old London submitted Typhoon off the Coast of Japan. It won first prize of $25, with second and third prizes going to men in their early twenties studying at the University of California and at Stanford University.

London also developing an interest in politics. He read about Eugene Debs being imprisoned for leading a rail-workers' strike in Chicago. He decided to join a march on Washington led by Jacob S. Coxley. The plan was to demand that Congress allocate funds to create jobs for the unemployed. In Oakland a young printer, Charles T. Kelly, assembled a detachment of two thousand men who would travel to the capital in box-cars provided free of charge by railroad companies anxious to shunt them east and thereby rid the region of potential trouble-makers. When the men reached Des Moines, Iowa, the railroad company decided the journey had come to an end.

It has been estimated that over $60 million was spent by prospectors during the Klondike Gold Rush but gold valued at $10 million was extracted from the ground. Jack London was one of those who arrived back home broke (he claimed he found only $4.50 in gold dust). However, the experience had provided him with some great experiences to write about: "I never realised a cent from any properties I had an interest in up there. Still, I have been managing to pan out a living ever since on the strength of the trip."

His first stories that he produced were rejected by magazine publishers. It took him six months before the highly regarded Overland Monthly, accepted the first of Jack London's Klondike stories, To The Man on Trail. This was followed by The White Silence that appeared in the February 1899 edition. It received a great reviews and established London was one of the country's most promising writers. George Hamlin Fitch, literary critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, concluded: "I would rather have written The White Silence than anything that has appeared in fiction in the last ten years." London was very disappointed that the magazine only paid him $7.50 for the story.

London now sent his short-stories to Atlantic Monthly, the most important literary magazine in New York City. In January 1900 they paid him $120 for An Odyssey of the North. This brought him to the attention of the publishers Houghton Mifflin, who suggested the idea of collecting his Alaska tales in book form. The result was The Son of the Wolf, which appeared in April 1900. Cornelia Atwood Pratt gave the book a great review: "His work is as discriminating as it is powerful. It has grace as well as terseness, and it makes the reader hopeful that the days of the giants are not yet gone by."

Jack London continued to be politically active and made public speeches on the merits of revolutionary socialism. He told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "I should like to have socialism.... yet I know that socialism is not the very next step; I know that capitalism must live its life first, that the world must be exploited to the utmost first; that first must intervene a struggle for life among the nations, severer, more widespread than before. I should much prefer to wake tomorrow in a smoothly-running socialist state but I know I shall not; I know it cannot come that way. I know that the child must go through the child's sickness before it becomes a man. So, always remember that I speak of things that are; not of things that should be."

In 1901 he agreed to exploit his growing fame by becoming the socialist candidate for Mayor of Oakland.The San Francisco Evening Post reported on 26th January, 1901: "Jack London is announced as a candidate for Mayor of Oakland... I don't know what a socialist is, but if it is anything like some of Jack London's stories, it must be something awful. I understand that as soon as Jack London is elected Mayor of Oakland by the Social Democrats the name of the place will be changed. The Social Democrats, however, have not yet decided whether they will call it London or Jacktown." London received just 246 votes (the winning candidate obtained 2,548). However, he was happy that he was able to bring the principles of socialism to a wider audience.

The New York City publisher, Samuel McClure offered to publish virtually anything Jack London produced. To obtain his services he agreed to pay him a retainer of $100. However, he was disappointed with his first novel, A Daughter of the Snows, and refused to serialize it in McClure's Magazine. McClure sold it to another publisher for $750 and it was published in 1902. Alex Kershaw argues that "A Daughter of the Snows was a badly executed jumble of his current intellectual confusions. Its disorganised melodrama and unconvincing characters failed to impress."

In July 1902 Jack London moved to England where he worked with the Social Democratic Federation. He was shocked by the poverty he saw and began writing a book about slum life in London. He wrote a letter to the poet, George Sterling, about the proposed book: "How often I think of you, over there on the other side of the world! I have heard of God's country, but this country is the country God has forgotten he forget. I've read of misery, and seen a bit; but this beats anything I could even have imagined. Actually, I have seen things and looked the second time in order to convince myself that it really is so. This I know, the stuff I'm turning out will have to be expurgated or it will never see magazine publication... You will read some of my feeble efforts to describe it some day. I have my book over one-quarter done and am bowling along in a rush to finish it and get out of here. I think I should die if I had to live two years in the East End of London."

In his notes, he wrote "if I were God one hour, I'd blot out all London and its 6,000,000 people, as Sodom and Gomorrah were blotted out, and look upon my work and call it good." Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997) has pointed out: "He (Jack London) was exhausted and emotionally drained. He had studied pamphlets, books and government reports on poverty, interviewed scores of men and women, taken hundreds of photographs, tramped miles of streets, stood in breadlines, slept in parks. What he had seen had seared his soul. London was more brutal in its unrelenting misery than the Klondike.... What made Jack such an effective but controversial reporter was his personal involvement. His greatest strength was his passionate bias in favour of capitalism's victims. He knew their suffering because he had felt it himself. His critics had not. Throughout his stay in London, memories of his youth had returned. Only by reassuring himself that he had escaped the conditions of his childhood could he control his fear that he might one day return to them."

The People of the Abyss was published by Macmillan in 1903. It was a surprise success, selling over twenty thousand copies in America. It was not as well received in England. Charles Masterman, who lived in the East End, and was the author of From the Abysss (1902) wrote in The Daily News: "Jack London has written of the East End of London as he wrote of the Klondike, with the same tortured phrase, vehemence of denunciation, splashes of colour, and ferocity of epithet. He has studied it 'earnestly and dispassionately' - in two months! It is all very pleasant, very American, and very young."

The reviewer in The Bookman accused Jack London of "snobbishness because of his profound consciousness of the gulf fixed between the poor denizens of the Abyss and the favoured class of which he is the proud representative ... he needs must assure the reader that in his own home he is accustomed to carefully prepared food and good clothes and daily tub - a fact that he might safely have left to be taken for granted".

The Call of the Wild was published in July 1903. It received extremely good reviews and critics hailed it as a "classic enriching American literature", "a spellbinding animal story", "a brilliant dramatisation of the laws of nature". The literary magazine, the Criterion, described it as: "The most virile, freshly conceived, dramatically told, and firmly sustained book of the season is unquestionably Jack London's Call of the Wild... Such books as these clarify the literary atmosphere and give a new, clean vibrant breath in a depression of romances and problems; they act like an invigorating wind from the open sea upon the dullness of a sultry day."

It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition of 10,000 copies sold out in 24 hours. Unfortunately for London, he had sold the rights of the book to his publisher for a flat fee of $2,000. Richard O'Connor, the author of Jack London: A Biography (1964), has argued that the novel was as good as anything Rudyard Kipling had written and had finally "struck the chord that awakened the fullest response" in American readers.

London followed The Call of the Wild with The Sea-Wolf (1904), The War of the Classes (1905), The Iron Heel (1907) and Martin Eden (1909), a book that sold a quarter of a million copies within a couple of months of being published in the United States. London, a heavy drinker, wrote about the problems of alcohol in his semi-autobiographical novel, John Barleycorn (1913). This was then used by the Women's Christian Temperance Union in its campaign for prohibition.

On this day in 1881 Mary Gawthorpe, the third of the five children of John Gawthorpe, leather worker in Leeds, and Anne Mountain, was born at 5 Melville Street. Her mother had done well at school but her family was extremely poor so from the age of ten had to work in the local textile mill. She had wanted to be a teacher and was determined to make sure her daughter finished her education.

At the age of thirteen Mary became a pupil teacher in the local Church of England school. Annie wanted her daughter to go to college but family finances meant that this was not possible. Instead, Mary worked during the day and studied in the evening and at weekends. Mary qualified as a schoolteacher just before her twenty-first birthday.

In 1901 Mary became friendly with Tom Garrs, a compositor on the Yorkshire Post. Tom was an active member of the Independent Labour Party and Mary began going to meetings with him. Mary Gawthorpe became converted to socialism and she soon developed a reputation as an extremely good public speaker. Mary also became a leading figure in the Leeds branch of the National Union of Teachers.

Mary Gawthorpe was a strong supporter of women's rights and with the help of her friends, Isabella Ford, and Ethel Annakin formed a Leeds branch of the Nation Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Mary was also active in the Women's Labour League. However, Mary gradually became disillusioned with the Labour Party's failure to organize men to help win the vote for women. In February 1906, Mary met Christabel Pankhurst after she spoke at a meeting in Leeds. Christabel told Mary that: "The further one goes the plainer one sees that men (even Labour men) think more of their own interests than of ours."

Mary joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in October 1905 after reading about the arrest and imprisonment of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney in Manchester. Tom Garrs disagreed with the militant activities of the WSPU and as a result of this disagreement, the couple parted.

In 1906 Mary gave up her job as a teacher and became the full-time organizer of the WSPU in Leeds. In October she was arrested with Dora Montefiore and Minnie Baldock during a demonstration outside the House of Commons and was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. After being released from Holloway Prison she became one of the WSPU's main speakers at rallies and demonstrations.

Mary suffered from poor health and in February 1907 she was operated on by Louisa Garrett Anderson for appendicitis. After leaving hospital she spent her convalescence with Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence at their home in Surrey. They also took Mary and Annie Kenney to Italy.

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Mary Gawthorpe, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Mary Gawthorpe also organised another successful rally at Heaton Park in Manchester that drew over 150,000 people. Her friend, Sylvia Pankhurst commented: "Mary Gawthorpe was a winsome merry creature, with bright hair and laughing hazel eyes, a face fresh and sweet as a flower, the dainty ways of a little bird, and having with all a shrewd tongue and so sparkling a fund of repartee, that she held dumb with astonished admiration, vast crowds of big, slow-thinking workmen and succeeded in winning to good-tempered appreciation the stubbornness opponents." Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy added: "Mary Gawthorpe... is a splendid speaker, full of humour, brilliant and lucid."

In 1909 Mary Gawthorpe heckled a speech given by Winston Churchill. Mary was badly beaten by stewards at the meeting and suffered severe internal injuries. Mary was also imprisoned several times while working for the WSPU. Hunger strikes and force-feeding badly damaged her health and in 1912 she had to abandon her active involvement in the movement.

Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "She (Mary Gawthorpe) went to Manchester to implement there a WSPU decision to hold large meetings in the principle cities in order to capitalize on the publicity and success of Hyde Park. She stayed as chief organizer for the WSPU in Lancashire until ill-health forced her to retire at the end of September 1910."

In March 1911 Dora Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the Women's Freedom League newspaper, The Vote. Marsden attempted to persuade the WFL to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left the journal. She now joined forces with Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Edmund Haynes, Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly."

Dora Marsden argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

During this period Dora Marsden developed loving relationships with several women, including Mary Gawthorpe, Rona Robinson, Grace Jardine and Harriet Shaw Weaver. In her letters to these women she often referred to them as "sweetheart". Her biographer, Les Garner, has argued: "Whether any of her friendships with women were sexual cannot be determined - certainly they were close and certainly too, Dora's personality and fragile beauty inspired many endearing comments from her friends. She appeared to have a special and unique quality that inspired devotion, if not awe, in some women.... Whether Dora was gay in the modern sense is unknown. There is no concrete evidence to support such a claim."

In March 1912, Mary Gawthorpe was unable to continue working as co-editor of The Freewoman. Marsden wrote in the journal that "we earnestly hope that the coming months will see her restored to health". Although Mary was ill, she had not resigned on health grounds, but because of what she claimed was "Dora's bullying" and her "philosophical anarchism". Gawthorpe returned all Dora's letters and asked her not to write again: "The sight of your letters I am obliged to confess turns me white with emotion and I have acute heart attacks following on from that."

Mary Gawthorpe's health gradually recovered and in 1916 she emigrated to the United States. She soon became active in the National Woman's Suffrage Party in New York City. After American women won the vote, Mary became involved in the trade union movement and in 1920 became a full-time official of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union.

On 19th July 1921 Mary married John Sanders and became an American citizen. As Sandra Stanley Holton has pointed out: "Throughout her life she retained her single name. She made a brief return to Britain in 1933, and was also in contact with the Suffragette Fellowship in these years. Little is known of her life after this date, though some of her surviving correspondence from the 1950s and 1960s shows that she remained keenly interested in political issues, and was still in touch with movements in Britain, including the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament."

In 1962 Mary Gawthorpe published Up Hill to Holloway, the story of her life up to her release from prison in November 1906. She died at her home in Long Island on 12th March 1973.

On this day in 1910 Luise Rainer was born into a Jewish family in Dusseldorf, Germany, on 12th January 1910. She was discovered by Max Reinhardt in 1926 and became part of his theatre company in Vienna. Rainer was only a teenager when she made her first film. This was followed by Sehnsucht (1932), Madame hat Besuch (1932) and Heut Kommt's Drauf (1933).

The American journalist, John Gunther, met her in 1934. Gunther's friend, William L. Shirer, pointed out that this caused problems for his relationship with his wife, Frances Fineman Gunther: "He fell for her to an extent that I don't think Frances was pleased. John had a roving eye and liked to flirt." Rainer later recalled: "He was tall, husky, and blond. He was, of course, very bright and had a great sense of humor. I thought he was a terribly nice fellow... However, I must say something simply and brusquely: I was never in love with him, or anything of that kind."

Rainer's Jewish background made her apprehensive w hen Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party gained power. In 1935 she moved to Hollywood and managed to obtain a seven-year contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. She was considered to be very beautiful but she later claimed: “I was nobody to make a pass to. I was very thin like a boy and I was very un-sexy.” Her first American role was in the film Escapade (1935). She was a last minute replacement for Myrna Loy. The star of the film, William Powell, was very impressed with Rainer and told MGM boss Louis B. Mayer, that she was a future star.

Despite this recommendation, she was only given a small part of Anna Held in The Great Ziegfeld (1936). The film was a great success and Rainer won the Oscar for Best Actress. The award was highly controversial at the time because her role was so short and relatively minor that it better qualified for a supporting nomination. One critic, Jon Hopwood has argued: "Most observers agree that Rainer won her Oscar as the result of her moving and poignant performance in just one, single scene in the picture, the famous telephone scene in which the broken-hearted Held congratulates Ziegfeld over the telephone on his upcoming marriage to Billie Burke while trying to retain her composure and her dignity. During the scene, the camera is entirely focused on Rainer, and she delivers a tour-de-force performance. Seventy years later, it remains one of the most famous scenes in movie history."

In 1937 Rainer married Clifford Odets, a member of the American Communist Party. His plays, Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing! and Till the Day I Die, established him as a champion of the underpriviledged. However, he had accepted a lucrative offer to become a film screenwriter and met Rainer on the set of Escapade.

In her next role, producer Irving Thalberg cast her in The Good Earth, based on the book of the same name by Pearl Buck. This resulted in her second Oscar for Best Actress. Rainer therefore became the first two-time Oscar winner in the two major acting categories. She was later asked if she was proud of these two performances. Rainer replied: "I was never proud of anything," she said. "I just did it like everything else. To do a film - let me explain to you - it's like having a baby. You labor, you labor, you labor, and then you have it. And then it grows up and it grows away from you. But to be proud of giving birth to a baby? Proud? No, every cow can do that." In another interview she said: "I don’t believe in acting. I think that people in life act, but when you are on the stage, or in my case also on screen, you have to be true."

A non-conformist actress, Rainer refused to accept the values of Hollywood. In 1937 Rainer had to be forced by Louis B. Mayer to receive her Oscar. She later claimed that: "For my second and third pictures I won Academy Awards. Nothing worse could have happened to me." Rainer next film was The Emperor's Candlesticks (1937). This was followed by The Big City (1937), Frou Frou (1938), The Great Waltz (1938) and Dramatic School (1938).

The studio insisted on forcing her into roles she considered unworthy of her talents. “All kinds of nonsense... I didn’t want to do it, and I walked out." Mayer said, "That girl is a Frankenstein, she’s going to ruin our whole firm... we made you and we are going to destroy you". Rainer decided to leave Hollywood. The director, Dorothy Arzner, claims that she was being badly treated because she had married a communist.

Louis B. Mayer took a keen interest in Rainer and on one occasion he asked her: "Why don't you sit on my lap when we're discussing your contract, the way the other girls." As Ken Cuthbertson pointed out: "As long as she was making money for him, Mayer tolerated Rainer's feistiness. After a couple of ill-conceived and unsuccessful movies, however, the two exchanged angry words" and their relationship came to an end.

In 1938 Rainer went to Europe where she helped provide aid to children who were victims of the Spanish Civil War. Rainer and her husband moved to New York City. They also spent time in Nichols, Connecticut. Rainer said that Odets was ''my passion’’ but was a possessive man. When Rainer developed a friendship with Albert Einstein, Odets was said to be so consumed with jealousy that he savaged a photograph of Einstein with a pair of scissors. The couple were divorced in 1943.

Rainer married Robert Knitte, a publisher, in 1945. After their marriage, she effectively abandoned film-making, living for a while in Switzerland and then Belgravia. She was later encouraged out of retirement to appear in The Gambler (1997).

When she reached her 100th birthday she told a friend that “The secret of a long life is to never trust a doctor." According to the Daily Telegraph, when a young man got up for her on a London bus, she looked at him and said: “Do I really look that old?” Luise Rainer died aged 104 on 30th December, 2014.

On this day in 1920 James Farmer was born in Marshall, Texas. An outstanding student, he obtained degrees from Wiley College (1938) and Howard University (1941).

Farmer and several Christian pacifists founded the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942. The organization's purpose was to apply direct challenges to American racism by using Gandhian tactics of non-violence. Farmer's religious beliefs resulted in him refusing to serve in the armed forces during the Second World War.

In 1947 Farmer participated in CORE's campaign of sit-ins which successfully ended two Chicago restaurants' discriminatory service practices against blacks. Articulate and charismatic, Farmer became CORE National Director in 1961. In this position he helped organize student sit-ins and Freedom Rides in the Deep South.

In 1966 Farmer resigned from Congress on Racial Equality in order to direct a national adult literacy project. A supporter of the Republican Party, Farmer failed in his attempt to win a seat in Congress in 1968. Shortly afterwards, the new president, Richard Nixon, appointed him Assistant Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare.

After leaving Nixon's administration in 1971, Farmer worked for the African American think tank, Council on Minority Planning and Strategy. In his final years Farmer completed his autobiography, Lay Bare the Heart (1985). James Farmer, who was awarded the Congressional Medal for Freedom in 1998, died on 9th July, 1999.