On this day on 11th November

On this day in 1860 the artist George Scharf died. Scarf was born in Mainburg, Bavaria on 23rd April, 1788. At the age of sixteen he went to Munich to study painting and lithography under Professor Hauber. A talented artist, Scarf soon found work producing lithographs for printers in Munich.

In 1810 Scarf left Munich and began travelling through France and Holland. He caught up in the Allied siege of Antwerp in January, 1814. He managed to escape and then enlisted in the English Army where he was employed to draw maps, sketches of fortifications and diagrams of troop movements. After seeing action at the Battle of Waterloo, Scarf returned to Paris.

In 1816, Scarf decided to emigrate to England. At first Scarf concentrated on political prints and cartoons. He produced pictures of the Spa Fields Riots (1817), the Westminster Election (1818), the Cato Street Conspirators (1820) a portrait of Arthur Thistlewood (1820) and the Coronation of George IV (1821) and London Street Advertisers (1824).

Scharf began working with German lithograph publishers who had settled in England. This included Rudolph Ackermann, Charles Hullmandel and Francis Moser. This involved the production of a large number of prints and paintings of London. These were mainly street scenes and incidents of ordinary London life. Scharf was especially interested in men at work. Two of his most paintings of this period were Laying a Water-Main in Tottenham Court Road (1834) and Railway Construction at Camden Town (1836).

On this day in 1866 Martha Annie Whiteley, English chemist and mathematician was born. During the First World War the chemical laboratories at the Imperial College were utilized to analyze samples collected from battlefields and areas that had been bombed. She and her colleagues focused on analyzing lachrymators and irritants. Whiteley worked with seven other female scientists in an experimental trench at Imperial College testing chemical weapons and explosives. The work was hazardous: Whitely wounded her arm whilst testing mustard gas on herself. She also worked on developing syntheses of drugs that had previously been imported from Germany including Beta-Eucaine, Phenacetin and Procaine.

On this day in 1880 Lucretia Mott, campaigner for women's rights died. Lucretia Coffin was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts, on 3rd January, 1793. At the age of thirteen Lucretia was sent to a boarding school run by the Society of Friends. She eventually became a teacher at the school. Her interest in women's rights began when she discovered that male teachers at the school were paid twice as much as the female staff.

In 1811 Lucretia married James Mott, another teacher at the school. Ten years later, she became a Quaker minister. Lucretia and her husband were both opposed to the slave trade and were active in the American Anti-Slavery Society. In 1840, Mott and her friend, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, travelled to London as delegates to the World Anti-Slavery Convention. Both women were furious when they, like the British women at the convention, were refused permission to speak at the meeting. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women."

However, it was not until 1848 that Mott and Stanton organised the Women's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls. Stanton's resolution that it was "the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves the sacred right to the elective franchise" was passed, and this became the focus of the group's campaign over the next few years. In 1866 Mott joined with Stanton and Lucy Stone to establish the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organisation became active in Kansas where Negro suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote.

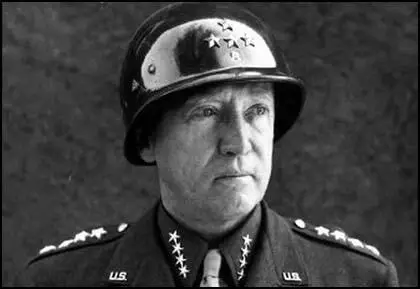

On this day in 1885 George Patton, American general was born. On 1st October 1940 Patton was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the 2nd Armed Division based at Fort Benning. Rated highly by General George Marshall, in January 1942, Patton was placed in charge of the Desert Training Centre at Indio, California. Later that year Patton joined General Dwight D. Eisenhower in organizing Operation Torch.

Patton's troops arrived in North Africa in November 1942. After liberating Morocco he worked on planning the invasion of Sicily with Mark Clark before being sent to Tunisia as head of the 2nd Corps. Patton was a strict disciplinarian and he insisted that his men shaved every day and wore a tie in battle.

On 10th July 1943, General Bernard Montgomery and the 8th Army landed at five points on the south-eastern tip of the island and the US 7th Army at three beaches to the west of the British forces. The Allied troops met little opposition and Patton and his troops quickly took Gela, Licata and Vittoria. The British landings were also unopposed and Syracuse was taken on the the same day. This was followed by Palazzolo (11th July), Augusta (13th July) and Vizzini (14th July), whereas the US troops took the Biscani airfield and Niscemi (14th July).

General Patton now moved to the west of the island and General Omar Bradley headed north and the German Army was forced to retreat to behind the Simeto River. Patton took Palermo on 22nd July cutting off 50,000 Italian troops in the west of the island. Patton now turned east along the northern coast of the island towards the port of Messina.

Meanwhile General Bernard Montgomery and the 8th Army were being held up by German forces under Field Marshal Albrecht Kesselring. The Allies carried out several amphibious assaults attempted to cut off the Germans but they were unable to stop the evacuation across the Messina Straits to the Italian mainland. This included 40,000 German and 60,000 Italian troops, as well as 10,000 German vehicles and 47 tanks.

On 17th August 1943, Patton and his troops marched into Messina. The capture of the island made it possible to clear the way for Allied shipping in the Mediterranean. It also helped to undermine the power of Benito Mussolini and Victor Emmanuel III forced him to resign.

During the campaign seventy-three Italian prisoners were murdered by soldiers in the 45th Division. General Omar Bradley ordered two men to face a general court-martial for premeditated murder. The men's main defence was that they were obeying orders issued by Patton in a speech he made to his soldiers on 27th June. Several soldiers said they were willing to give evidence that Patton had told then to take no prisoners. One officer claimed that Patton had said: "The more prisoners we took, the more we'd have to feed, and not to fool with prisoners." In order to protect Patton from the charge of war crimes, Bradley decided to drop the investigation into the murder of the Italian soldiers.

Patton also created controversy when he visited the 15th Evacuation Hospital on 3rd August 1943. In the hospital he encountered Private Charles H. Kuhl, who had been admitted suffering from shellshock. When Patton asked him why he had been admitted, Kuhl told him "I guess I can't take it." According to one eyewitness Patton "slapped his face with a glove, raised him to his feet by the collar of his shirt and pushed him out of the tent with a kick in the rear." Kuhl was later to claim that he thought Patton, as well as himself, was suffering from combat fatigue.

Two days after the incident at the 15th Evacuation Hospital Patton sent a memo to all commanders in the 7th Army: "It has come to my attention that a very small number of soldiers are going to the hospital on the pretext that they are nervously incapable of combat. Such men are cowards and bring discredit on the army and disgrace to their comrades, whom they heartlessly leave to endure the dangers of battle while they, themselves, use the hospital as a means of escape. You will take measures to see that such cases are not sent to the hospital but are dealt with in their units. Those who are not willing to fight will be tried by court-martial for cowardice in the face of the enemy."

On 10th August 1943, Patton visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital to see if there were any soldiers claiming to be suffering from combat fatigue. He found Private Paul G. Bennett, an artilleryman with the 13th Field Artillery Brigade. When asked what the problem was, Bennett replied, "It's my nerves, I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton exploded: "Your nerves. Hell, you are just a goddamned coward, you yellow son of a bitch. Shut up that goddamned crying. I won't have these brave men here who have been shot seeing a yellow bastard sitting here crying. You're a disgrace to the Army and you're going back to the front to fight, although that's too good for you. You ought to be lined up against a wall and shot. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself right now, God damn you!" With this Patton pulled his pistol from its holster and waved it in front of Bennett's face. After putting his pistol way he hit the man twice in the head with his fist. The hospital commander, Colonel Donald E. Currier, then intervened and got in between the two men.

Colonel Richard T. Arnest, the man's doctor, sent a report of the incident to General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The story was also passed to the four newsmen attached to the Seventh Army. Although Patton had committed a court-martial offence by striking an enlisted man, the reporters agreed not to publish the story. Quentin Reynolds of Collier's Weekly agreed to keep quiet but argued that there were "at least 50,000 American soldiers on Sicily who would shoot Patton if they had the chance."

Eisenhower told one of his senior officers: "If this thing ever gets out, they'll be howling for Patton's scalp, and that will be the end of George's service in this war. I simply cannot let that happen. Patton is indispensable to the war effort - one of the guarantors of our victory." Instead he wrote a letter to Patton demanding that he should apologize or make "personal amends to the individuals concerned as may be within your power."

Eisenhower now had a meeting with the war correspondents who knew about the incident and told them that he hoped they would keep the "matter quiet in the interests of retaining a commander whose leadership he considered vital." The men agreed to do this but Ernest Cuneo, who worked for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), passed this story to Drew Pearson and in November 1943, he told the story on his weekly syndicated radio program. Some politicians demanded that Patton should be sacked but General George Marshall and Henry L. Stimson supported the way General Eisenhower had dealt with the case.

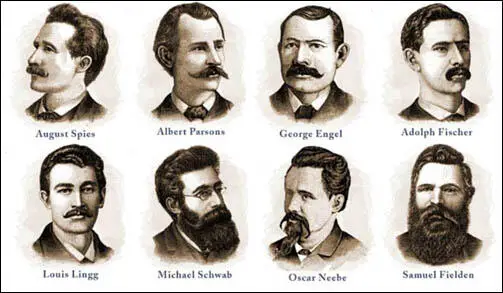

On this day in 1887 August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fisher and George Engel are executed as a result of the Haymarket bombing. On 1st May, 1886 a strike was began throughout the United States in support a eight-hour day. Over the next few days over 340,000 men and women withdrew their labor. Over a quarter of these strikers were from Chicago and the employers were so shocked by this show of unity that 45,000 workers in the city were immediately granted a shorter workday.

The campaign for the eight-hour day was organised by the International Working Men's Association (the First International). On 3rd May, the IWPA in Chicago held a rally outside the McCormick Harvester Works, where 1,400 workers were on strike. They were joined by 6,000 lumber-shovers, who had also withdrawn their labour. While August Spies, one of the leaders of the IWPA was making a speech, the police arrived and opened-fire on the crowd, killing four of the workers.

The following day August Spies, who was editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, published a leaflet in English and German entitled: Revenge! Workingmen to Arms!. It included the passage: "They killed the poor wretches because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them to show you 'Free American Citizens' that you must be satisfied with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed. If you are men, if you are the sons of your grand sires, who have shed their blood to free you, then you will rise in your might, Hercules, and destroy the hideous monster that seeks to destroy you. To arms we call you, to arms." Spies also published a second leaflet calling for a mass protest at Haymarket Square that evening.

On 4th May, over 3,000 people turned up at the Haymarket meeting. Speeches were made by August Spies, Albert Parsons and Samuel Fielden. At 10 a.m. Captain John Bonfield and 180 policemen arrived on the scene. Bonfield was telling the crowd to "disperse immediately and peaceably" when someone threw a bomb into the police ranks from one of the alleys that led into the square. It exploded killing eight men and wounding sixty-seven others. The police then immediately attacked the crowd. A number of people were killed (the exact number was never disclosed) and over 200 were badly injured.

Several people identified Rudolph Schnaubelt as the man who threw the bomb. He was arrested but was later released without charge. It was later claimed that Schnaubelt was an agent provocateur in the pay of the authorities. After the release of Schnaubelt, the police arrested Samuel Fielden, an Englishman, and six German immigrants, August Spies, Adolph Fisher, Louis Lingg, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab. The police also sought Albert Parsons, the leader of the International Working Peoples Association in Chicago, but he went into hiding and was able to avoid capture. However, on the morning of the trial, Parsons arrived in court to standby his comrades.

There were plenty of witnesses who were able to prove that none of the eight men threw the bomb. The authorities therefore decided to charge them with conspiracy to commit murder. The prosecution case was that these men had made speeches and written articles that had encouraged the unnamed man at the Haymarket to throw the bomb at the police.

The jury was chosen by a special bailiff instead of being selected at random. One of those picked was a relative of one of the police victims. Julius Grinnell, the State's Attorney, told the jury: "Convict these men make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions."

At the trial it emerged that Andrew Johnson, a detective from the Pinkerton Agency, had infiltrated the group and had been collecting evidence about the men. Johnson claimed that at anarchist meetings these men had talked about using violence. Reporters who had also attended International Working Peoples Association meetings also testified that the defendants had talked about using force to "overthrow the system".

During the trial the judge allowed the jury to read speeches and articles by the defendants where they had argued in favour of using violence to obtain political change. The judge then told the jury that if they believed, from the evidence, that these speeches and articles contributed toward the throwing of the bomb, they were justified in finding the defendants guilty.

All the men were found guilty: Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, Louis Lingg and George Engel were given the death penalty. Whereas Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab were sentenced to life imprisonment. On 10th November, 1887, Lingg committed suicide by exploding a dynamite cap in his mouth. The following day Parsons, Spies, Fisher and Engel mounted the gallows. As the noose was placed around his neck, Spies shouted out: "There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

Many people believed that the men had not been given a fair trial and in 1893, John Peter Altgeld, the new governor of Illinois, pardoned Oscar Neebe, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab. Altgeld argued: "It is further shown here that much of the evidence given at the trial was a pure fabrication; that some of the prominent police officials, in their zeal, not only terrorized ignorant men by throwing them into prison and threatening them with torture if they refused to swear to anything desired but that they offered money and employment to those who would consent to do this. Further, that they deliberately planned to have fictitious conspiracies formed in order that they might get the glory of discovering them."

David Roediger has argued: "Haymarket's bomb echoed long and deep. The explosion and ensuing repression decimated the anarchist labor movement, though the martyred defendants became heroes to many and inspired countless individual conversions to anarchism and to socialism... The pardons ruined Altgeld's promising political career. The tactic of the mass strike was far less appealing to pragmatic U.S. labor leaders after Haymarket, and the idea of self-defense by labor never again received so broad a hearing on the national scale."

On this day in 1896 Shirley Graham Du Bois, American author, playwright, composer, and activist for African-American causes was born. In 1932 she composed the opera Tom-Tom: An Epic of Music and the Negro which premiered in Cleveland, Ohio, commissioned by the Stadium Opera Company. It featured an all Black cast and orchestra, structured in three acts; act one taking place in an Indigenous African tribe, act two portraying an American Slave plantation, and the final act taking place in 1920s Harlem. The music features elements of blues and spirituals, as well as jazz with elements of opera.

Shirley Graham worked at the Federal Theatre Project but it was accused of being too left-wing. J. Parnell Thomas objected to the radical message in some of these plays. Thomas claimed that: "Practically every play presented under the auspices of the Project is sheer propaganda for Communism or the New Deal." Martin Dies, the chairman of the Un-American Activities Committee, called for the resignations of Harold Ickes, Harry Hopkins and Frances Perkins, as the three had "associates who were Socialists, Communists, and crackpots."

Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to sack these three members of his government but Congress bring the Federal Theatre Project to an end and allowed the other projects to continue only if they found local sponsors who would bear 25 per cent of the cost. During its four years existence the FTP launched or established the careers of such artists as Orson Welles, John Houseman, Will Geer, Arthur Miller, Paul Green, Marc Blitzstein, Canada Lee and Elmer Rice. (11)

Elmer Rice later wrote: "Nationally, the Theatre Project's record was extraordinary. At one time forty-two separate units were in operation in twenty states, with a total of nearly thirteen thousand employees... In its first three years the Theatre Project had produced more than nine hundred different plays, for a total of nearly 55,000 performances, many of them free, none charging more than a dollar. The attendances figures exceeded 26,000,000... In the project's fourth year, Congress killed it... Its demise was perhaps the most tragic occurrence in the cultural history of the United States. Had funds been provided for continuance, upon an artistic basis divorced from unemployment relief, of those units that had clearly demonstrated their worth, the foundation would have been laid for a nationwide theatrical structure that would have brought enlightenment and enjoyment to millions, and stimulation to artistic creation. The cost, compared to the billions expended annually upon weapons of destruction, would have been infinitesimal."

In 1947 Roy Brewer, a close friend of Ronald Reagan was appointed to the Motion Picture Industry Council. Brewer later commissioned a booklet entitled Red Channels. Published on 22nd June, 1950, and written by Ted C. Kirkpatrick, a former FBI agent and Vincent Hartnett, a right-wing television producer, it listed the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. Shirley Graham Du Bois name appeared in the booklet and her work being pulled from libraries and censored.

On this day in 1914 Daisy Bates, civil rights activist, was born in Huttig, Arkansas, in 1912. When Daisy was eight her mother was killed during an attempt by three white men to rape her. At the age of fifteen Daisy met L. C. Bates. The couple eventually got married and began publishing Arkansas State Press. The newspaper played an important role in the civil rights movement and attacked segregation in Arkansas.

Daisy Bates was an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and in 1952 was elected president of the chapter in Arkansas. After the Supreme Court announced in 1954 that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional. Some states accepted the ruling and began to desegregate. This was especially true of states that had small black populations and had found the provision of separate schools extremely expensive.

However, several states in the Deep South, including Arkansas, refused to accept the judgment of the Supreme Court. Bates now started to campaign for desegregated schools and in 1957 was a key figure in the campaign to get black students accepted by Central High School in Little Rock. Bates involvement in the civil rights movement resulted in a large slump in the advertising revenue of the Arkansas State Press and it closed in 1959. Her book, The Long Shadow of Little Rock, was published in 1962. Bates was the only woman who spoke at the March on Washington in 1963.

President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Bates to help administer his anti-poverty programs. She also worked in Washington for the Democratic National Committee. In 1968 Bates was appointed director of the Mitchellville OEO Self-Help Project.

On this day in 1914 Howard Fast, the son of a factory worker, was born in New York City. Fast became a socialist after reading The Iron Heel, a novel written by Jack London. "The Iron Heel was my first real contact with socialism; the book... had a tremendous effect on me. London anticipated fascism as no other writer of the time did." He dropped out of high school and at the age of 18 published his first novel Two Villages. Fast held strong left-wing views and a large number of his novels dealt with political themes. This included a series of three books on the American Revolutionary War period: Conceived in Liberty (1939), The Unvanquished (1942), and Citizen Tom Paine (1943).

In 1943 Fast joined the American Communist Party. As he later recalled: "In the party I found ambition, narrowness and hatred; I also found love and dedication and high courage and integrity - and some of the noblest human beings I have ever known." His Marxist views were reflected in the novels that he wrote during this period. This included Freedom Road (1944), a novel that dealt with the Reconstruction era; The American (1946) and a fictionalized biography of the radical Illinois governor, John Peter Altgeld.

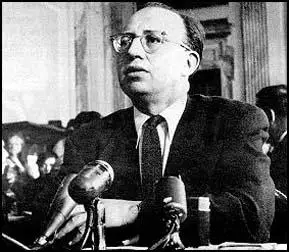

In 1950 Fast was ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. because he had contributed to the support of a hospital for Popular Front forces in Toulouse during the Spanish Civil War. When he appeared before the HUAC he efused to name fellow members of American Communist Party, claiming that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and he was sentenced to three months in prison.

In 1950 Howard Fast attempted to get his novel about, Spartacus, an account of the 71 B.C. slave revolt, published. Eight major publishers rejected it. Alfred Knopf sent the manuscript back unopened, saying he wouldn't even look at the work of a traitor. Fast now realised he was blacklisted and formed his own company, the Blue Heron Press, to publish Spartacus (1951). He continued write and publish books that reflected his left-wing views. This included Silas Timberman (1954), a novel about a victim of McCarthyism and The Story of Lola Gregg (1956), describing the FBI pursuit and capture of a communist trade unionist. Fast also worked as a staff writer for the Daily Worker.

Un-American Activities Committee in 1950.

On this day in 1918 the Armistice brought the First World War to an end. By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks."

The German Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the Reichstag demanded the resignation of Kaiser Wilhem II. When that was refused, they resigned from the Reichstag and called for a general strike throughout Germany. In Munich, Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic.

Later that day, in order to stop the spread of the revolution, the German government agreed to surrender. On 9th November, the Kaiser abdicated fled to Holland. At 5 a.m. on 11th November, 1918, signed the armistice. It came into force at 11 a.m. All territorial conquests achieved by the Central Powers had to be abandoned. The German Army also surrendered 30,000 machine-guns, 2,000 aircraft, 5,000 locomotives, 5,000 lorries and all its submarines.

On this day in 1946 Selina Cooper died, shortly before her eighty-second birthday.

Selina Coombe, the daughter of Charles Coombe and Jane Coombe, was born in Callington on 4th December 1864. Selina's father was a navvy and was away working on a construction job when he died of typhoid fever. Jane, her two youngest children and her seventy-four year old mother were all left destitute by Charles Coomber's death. There was little work in Cornwall so Jane decided to follow the example of two eldest sons, Richard and Charles, and seek work in the textile mills of northern England.

Jane Coombe, and her two youngest children, Selina and Alfred, settled in Barnoldswick in 1876. Selina and Alfred soon found work in the local textile mill. Selina, who was now twelve years old, spent half the day in the factory and the other half at school. She was employed as a "creeler" and it was her responsibility to make sure there was a constant supply of fresh bobbins for the cotton emerging from the card frames. When Selina reached the age of thirteen she was able to leave school and work full-time in the Barnoldswick Mill. Selina received eight shillings for a fifty-six hour week, and this enabled the family to move out of temporary accommodation and rent a small house close to the mill.

Jane's rheumatism continued to get worse and soon after arriving in Barnoldswick she was restricted to staying at home. Jane Coombe carried on taking in work as a dressmaker but by 1882 her rheumatism became so bad that she could no longer walk. Selina now had to leave Barnoldswick to look after her bed-ridden mother. Luckily, Jane retained the use of her hands and so with a small sewing machined fixed to a board, she still able to make the clothes that were so highly valued in the neighbourhood. To raise extra money Selina took in washing.

When Jane Coombe died in 1889, Selina was able to return to work in the factory. Selina joined the Nelson branch of the Cotton Worker's Union. Although the vast majority of members were women, the union was run by men. Selina thought that was unfair as it influenced the issues that the union became involved in. Selina for example, objected to the system of providing toilets without doors. In 1891 Selina became involved in a trade union dispute where attempts were made to force employers to provide decent toilet facilities. Selina also objected to the way that male overlookers treated young women workers in factory. However, the male leadership of the union showed little interest in these complaints about sexual harassment.

As well as her union activities, Selina also began attending education classes organised by the Women's Co-operative Guild in Nelson. By 1889 the General Secretary of the Guild was Margaret Llewelyn Davies, who had recently completed her university studies at Girton College, that had been founded by her aunt, Emily Davies, in 1869.

One of the main objectives of the Women's Co-operative Guild was to encourage women to "discuss matters beyond the narrow confines of their domestic lives." Selina also began reading books about history and was gradually building up her knowledge of politics. She also starting buying medical books so that she would be able to advise fellow workers who were unable to afford a visit to the doctors. Her collection included The Law of Population, a book written by Annie Besant on birth-control.

In 1892 the Independent Labour Party (ILP) was formed in Nelson. Selina was attracted to the party's claims that it supported equal rights for women. It was at the local ILP that Selina met Robert Cooper, a local weaver who was a committed socialist and advocate of women's suffrage. Cooper had previously worked for the Post Office but had been sacked for his trade union activities.

Selina married Robert Cooper in 1896 and despite giving birth to a couple of children in the first three years of marriage, she continued her involvement in politics. Selina's first child, John Ruskin, who was named after the writer who had most influenced her political ideas, died of bronchitis when he was four months old.

In 1900 Selina Cooper joined the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage. Other members at the time included Esther Roper, Eva Gore-Booth, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Cooper wrote at the time: "(a) That in the opinion of your petitioners the continued denial of the franchise to women is unjust and inexpedient. (b) In the home, their position is lowered by such an exclusion from the responsibilities of national life. (c) In the factory, their unrepresented condition places the regulation of their work in the hands of men who are often their rivals as well as their fellow workers."

Selina helped organize a petition that was signed by women working in the Lancashire cotton mills. Selina alone collected the signatures of 800 women from local textile factories. By spring 1901, 29,359 women from Lancashire had signed the petition in favour of women's suffrage and Selina was chosen as one of the delegates to present the petition to the House of Commons.

In 1901 the Independent Labour Party asked Selina to stand as a candidate for the forthcoming Poor Law Guardian elections. Although women had been allowed to stand as candidates since the passing of the Municipal Franchise Act in 1869, no working-class woman had ever been elected to one of these bodies. Although the local newspapers campaigned against Selina Cooper, she was elected.

Selina was outvoted on most issues but she did persuade the Board of Guardians to allow elderly people in the workhouse more freedom of movement. Although her duties as a Guardian took up a lot of her time, Selina continued to campaign for women's suffrage. At the National Conference of the Labour Party in 1905, Selina made a speech where she urged the leadership to fully support women's suffrage. The following year she helped form the Nelson and District Suffrage Society.

Selina developed a national reputation for her passionate speeches in favour of women's rights. Millicent Fawcett was a great admirer of Selina Cooper and she was often asked to speak at NUWSS rallies. In 1910 she was chosen to be one of the four women to present the case for women's suffrage to Herbert Asquith, the British Prime Minister.

In 1911 Selina Cooper and Ada Nield Chew became organizers for the NUWSS. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She spent the next years travelling around the country; in 1908, for instance, she took part in at least eight by-elections. When she was away from home the NUWSS paid the expense of a housekeeper to care for her daughter, who had been born in 1900."

Cooper influenced the NUWSS decision in April 1912 to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. Emily Davies, a member of the Conservative Party, and Margery Corbett-Ashby, an active supporter of the Liberal Party, resigned from the NUWSS over this decision. However, others like Catherine Osler, resigned from the Women's Liberal Federation in protest against the government's attitude to the suffrage question.

The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Catherine Marshall, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden.

In August 1913 Selina Cooper wrote in The Common Cause: "One reason why I am a convinced suffragist is that the mothers (even as wage earners) take the greater share of the responsibility in the upbringing of their children; therefore, they ought to have the greater means, not the less, to enable them to do justice to the rising generation."

During the First World War Selina worked on several committees organizing relief work in Nelson. This included Nelson's first ever Maternity Centre. Selina took great pleasure in the fact that she personally helped to deliver fifteen babies during this period.

Although willing to help people suffering from the consequences of the war, Selina, who was a pacifist, refused to take part in army recruiting campaigns. Selina was totally opposed to military conscription and after its introduction in 1916, became involved in helping those men who were sent to prison for refusing to fight. In 1917 Selina persuaded over a thousand women in Nelson to take part in a Women's Peace Crusade procession. The meeting ended in a riot and mounted police had to be called in to protect Selina Cooper and Margaret Bondfield, the two main speakers at the meeting.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 the NUWSS tried to persuade the Labour Party in Nelson to choose Selina Cooper as their candidate in the forthcoming 1918 General Election. However, the Labour Party was very much a male-dominated organisation and no women were selected to fight winnable seats.

Selina Cooper continued to be involved in local politics. She was elected to the town council and became a local magistrate. In the 1930s she played a prominent role in the campaign against fascism.