On this day on 10th February

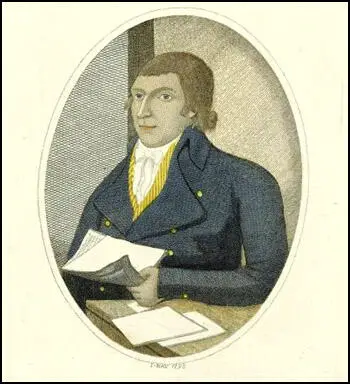

On this day in 1768 parliamentary reformer George Mealmaker was born. Mealmaker, the son of a weaver, was born in Dundee on 10th February, 1768. George followed his father's trade and became a successful handloom weaver. During the 1780s Mealmaker became interested in politics and with Thomas Fyshe Palmer helped to form the Dundee Friends of Liberty group.

In 1793 Mealmaker wrote a pamphlet Dundee Address to the Friends of Liberty that criticised the "despotism and tyranny" of the British government and opposed the war with France. On 12th September 1793 Thomas Fyshe Palmer was arrested and charged with writing the pamphlet. The authorities claimed that the pamphlet was "calculated to produce a spirit of discontent in the minds of the people against the present happy constitution and government of this country, and to rouse them up to acts of outrage and violence". At the trial, George Mealmaker, gave evidence that he, and not Palmer, had written this pamphlet. Despite this evidence Palmer was found guilty and sentenced to be transported to Australia for seven years.

The British government hoped that the transporting of Palmer and the other leaders of the Scottish Radicals, Thomas Muir and William Skirving, would bring an end to the demands for parliamentary reform. However, George Mealmaker refused to be silenced and continued to campaign for universal suffrage. Mealmaker explained his ideas on democracy in his pamphlet The Moral and Political Catechism of Man (1797). As a result of the publication of this pamphlet, Mealmaker was arrested and charged with sedition. In January 1798 he was found guilty and sentenced to 14 years transportation.

Mealmaker arrived at Port Jackson aboard the Royal Admiral on 21st November 1800. He was no doubt looking forward to being with the other members of the Friends of Liberty who had been transported earlier. However, only Maurice Margarot of the original five Scottish Martyrs was still in captivity. William Skirving, Joseph Gerrald and Thomas Muir were dead and Thomas Fyshe Palmer had finished his sentence and was just about to travel back to Britain.

Governor Philip King was pleased to have a skilled worker in the colony and put Mealmaker in charge of a weaving factory in Parramatta. George Mealmaker died on 30th March, 1808. In a letter written to his wife, Marjory Mealmaker, Lord Liverpool, Secretary of State for the Colonies, claimed that her husband had "suffocated by drinking spirits".

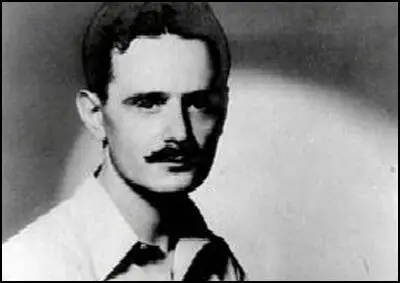

On this day in 1890 Fanya Kaplan was born, into a poor peasant family and her four brothers and two sisters were all educated at home. Her parents both emigrated to the United States.

Kaplan became involved in radical politics and joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party. In 1906 she took part in a plot to kill a Tsarist official in Kiev. Kaplan was caught and sentenced to a life of hard labour in Siberia. She later recalled: "I was exiled to Akatoi for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent eleven years at hard labour."

After eleven years in Siberia she was released after the February Revolution. Like many Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, Kaplan was furious when the Bolsheviks closed down the Constituent Assembly and decided that she would assassinate Lenin as a means of protesting against this measure.

On 30th August, 1918, Lenin spoke at a meeting in Moscow. Victor Serge later explained what happened: "Lenin arrived alone; no one escorted him and no one formed a reception party. When he came out, workers surrounded him for a moment a few paces from his car." As he left the building Kaplan tried to ask Lenin some questions about the way he was running the country. Just before he got into his car Lenin turned to answer the woman. Serge then explained what happened next: "It was at this moment Kaplan fired at him, three times, wounding him seriously in the neck and shoulder. Lenin was driven back to the Kremlin by his chauffeur, and just had the strength to walk upstairs in silence to the second floor: then he fell in pain. There was great anxiety for him: the wound in the neck could have proved extremely serious; for a while it was thought that he was dying."

Fanya Kaplan was soon captured and in a statement she made to Cheka that night, she explained that she had attempted to kill him because he had closed down the Constituent Assembly. In a statement to the police she confessed to trying to kill Lenin. "My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot at Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it."

Fanya Kaplan was shot by Pavel Malkov, a Baltic Fleet sailor, on 3rd September, 1918. Yakov Sverdlov, who organized the execution, gave instructions that she was not to be buried. He told Malkov: "her remains are to be destroyed so that not a trace remains." Malkov later recalled: "The execution of a human being, especially a woman, was no easy thing. It was a heavy, very heavy responsibility. But I had never been ordered to carry out a more just sentence than this."

The attempt on Lenin's life and the assassination of Moisei Uritsky, chief of the Petrograd Secret Police, concerned the leadership of the Bolsheviks. Joseph Stalin, who was in Tsaritsyn at the time, sent a telegram to Yakov Sverdlov suggesting: "having learned about the wicked attempt of capitalist hirelings on the life of the greatest revolutionary, the tested leader and teacher of the proletariat, Comrade Lenin, answer this base attack from ambush with the organization of open and systematic mass terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents."

Leon Trotsky agreed and argued in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930): "The Socialist-Revolutionaries had killed Volodarsky and Uritzky, had wounded Lenin seriously, and had made two attempts to blow up my train. We could not treat this lightly. Although we did not regard it from the idealistic point of view of our enemies, we appreciated the role of the individual in history. We could not close our eyes to the danger that threatened the revolution if we were to allow our enemies to shoot down, one by one, the whole leading group of our party."

The Bolsheviks newspaper, Krasnaya Gazeta, reported on 1st September, 1918: "We will turn our hearts into steel, which we will temper in the fire of suffering and the blood of fighters for freedom. We will make our hearts cruel, hard, and immovable, so that no mercy will enter them, and so that they will not quiver at the sight of a sea of enemy blood. We will let loose the floodgates of that sea. Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands; let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky, Zinovief and Volodarski, let there be floods of the blood of the bourgeois - more blood, as much as possible."

The advice of Stalin, who had used these tactics successfully in Tsaritsyn, was accepted and in September, 1918, Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the Cheka, instigated the Red Terror. It is estimated that in the few months after the attempt on the life of Lenin, over 800 socialists were arrested and shot without trial. A Foreign Office report in February, 1919, claimed: "The political parties which have been most oppressed by the Bolsheviks are the Socialists, Social Democrats and Social Revolutionaries. Owing to bribery and corruption - those notorious evils of the old regime which are now multiplied under Bolshevism - capitalists were able to get their money from the banks and their securities from safe deposits, and managed to get away. On the other hand, many members of the Liberal and Socialist parties who have worked all the time for the revolution, have been arrested or shot by the Bolsheviks."

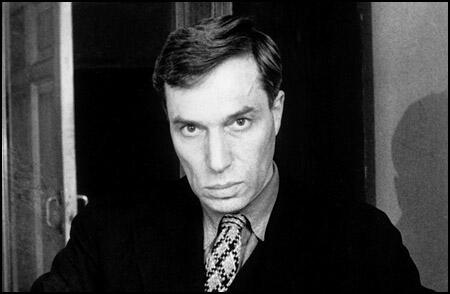

On this day in 1890 the novelist Boris Pasternak, the son of Jewish parents, was born in Moscow, Russia. His father was a painter and his mother a talented pianist.

Pasternak studied music and philosophy at Moscow University and the University of Marburg in Germany. He began writing poetry and his first volume, A Twin in the Clouds (1914).

During the First World War Pasternak worked in a chemical factory in the Urals. He continued writing and the publication of My Sister Life (1922), Spektorski (1926), 1905 (1925), Lieutenant Schmidt (1926) and The Second Birth (1932) established him as the Soviet Union's most important poet.

Pasternak's poetry did not reflect the dominant ideology of Socialist Realism and during the purges in the 1930s he stayed out of prison by concentrating on translating the work of other European writers.

In 1956 Pasternak submitted a novel, Doctor Zhivago, for publication. It was rejected because the publisher disapproved of its treatment of the October Revolution. The manuscript was smuggled out of the country and over the next two years was published in 18 different languages. The Soviet government threatened to deport Pasternak and he was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers. Boris Pasternak died in Peredelkino, on 30th May, 1960.

On this day in 1894 Harold Macmillan, the grandson of Daniel Macmillan (1813-1857), the publisher, was born in 1894. In his memoirs he described his mother as having "high standards and demanding high performances". He added: "I can truthfully say that I owe everything all through my life to my mother's devotion and support".

Macmillan attended Summer Fields School in Oxford. He later admitted that his shyness caused him problems at school and that he returned home with a "perpetual terror of becoming in any way conspicuous". He also suffered from periods of depression: "I was oppressed by some kind of mysterious power which would be sure to get me in the end. One felt that something unpleasant was more likely to happen than anything pleasant."

In 1906 Macmillan won a scholarship to Eton. However, over the next three years he suffered poor health. His biographer, Alistair Horne, wrote in Macmillan: The Making of a Prime Minister (1988): "Harold never finished Eton. He seems to have suffered from poor health and in his first half contracted pneumonia, from which he only just survived. Three years later some form of heart trouble was evidently diagnosed, and in 1909 he returned home as a semi-invalid."

Macmillan won a place at Balliol College in 1912. His personal tutor was Ronald Knox, who became an important influence on his intellectual development. Macmillan later recalled: "He influenced me because he was a saint... the only man I have ever known who really was a saint." Soon afterwards Knox became an Anglican Chaplain.

While at university Macmillan became involved in politics. He joined the Canning Club (Conservative), the Russell Club (Liberal) and the Fabian Society (Socialist). At meetings of the Oxford Union he supported progressive causes such as women's suffrage. He also voted for the motion: "That this House approves the main principles of socialism." Macmillan supported the "radical wing" of the Liberal Party during this period and was greatly impressed with David Lloyd George, who made an entertaining speech at the university in 1913.

He was elected Secretary of the Oxford Union in November 1913 and was fully expected to eventually become President of the Union if it had not been for the outbreak of the First World War. At the time Macmillan was suffering from appendicitis but as soon as he recovered he joined the Grenadier Guards. He was commissioned and as a second lieutenant he was sent to a training battalion at Southend-on-Sea.

Harold Macmillan left for France on 15th August, 1915. When they arrived on the Western Front one of Macmillan's tasks was to read and censor the letters that his men sent home to their loved ones. He wrote to his mother about this task: "They have big hearts, these soldiers, and it is a very pathetic task to have to read all their letters home. Some of the older men, with wives and families who write every day, have in their style a wonderful simplicity which is almost great literature.... And then there comes occasionally a grim sentence or two, which reveals in a flash a sordid family drama."

On 27th September 1915, Macmillan took part in the offensive at Loos. Macmillan remembered being addressed by the Corps Commander, who assured them, "Behind you, gentlemen, in your companies and battalions, will be your Brigadier; behind him your Divisional Commander, and behind you all - I shall be there." At that point Macmillan heard a fellow officer comment in a loud stage whisper, "Yes, and a long way behind too!".

Macmillan was shot through his right hand towards the end of the battle. He was evacuated to hospital and although it was not a serious wound he never recovered the strength of that hand, which affected the standard of his handwriting. It also was responsible for what became known as "limp handshake". The British Army lost nearly 60,000 men at Loos for the advance of just a couple of miles.

After receiving treatment in London Macmillan was sent back to the Western Front in April 1916. The following month he gave an insight into life in the trenches. "Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about a modern battlefield is the desolation and emptiness of it all.... One cannot emphasise this point too much. Nothing is to be seen of war or soldiers -only the split and shattered trees and the burst of an occasional shell reveal anything of the truth. One can look for miles and see no human being. But in those miles of country lurk (like moles or rats, it seems) thousands, even hundreds of thousands of men, planning against each other perpetually some new device of death. Never showing themselves, they launch at each other bullet, bomb, aerial torpedo, and shell."

Macmillan took part in the offensive at the Somme. In July 1916, Macmillan was wounded while leading a patrol in No Man's Land: "They challenged us, but we could not see them to shoot, and of course they were entrenched while we were in the open. So I motioned to my men to lie quite still in the long grass. Then they, began throwing bombs at us at random. The first, unluckily, hit l me in the face and back and stunned me for the moment."

Macmillan was only in hospital for a couple of days and by the end of the month he moved with his battalion to Beaumont-Hamel. He wrote to his mother that the area was beautiful and that it was "not the weather for killing people." In another letter he said "the flies are again a terrible plague, and the stench from the dead bodies which lie in heaps around is awful."

On 15th September 1916 Macmillan was wounded again during an attack on the German trenches. Shot in the leg he took refuge in a shell-hole where he "pretended to be dead when any Germans came near." He took morphine which sent him into a deep sleep until he was found by members of the Sherwood Foresters.

Once again he described to his mother what happened during the attack: "The German artillery barrage was very heavy, but we got through I the worst of it after the first half-hour. I was wounded slightly in the right knee. I bound up the wound at the first halt, and was able to go on... About 8.20 we halted again. We found that we were being held up on the left by Germans in about 500 yards of uncleared trench. We attempted to bomb and rush down the trench. I was taking a party across to the left with a Lewis gun, to try and get in to the trench, when I was wounded by a bullet in the left thigh (apparently at close range). It was a severe wound, and I was quite helpless. I dropped into a shell-hole, shouted to Sgt. Robinson to take command of my party and go on with the attack."

Macmillan had received serious wounds and the surgeons decided it would be too risky to attempt to remove the bullet fragments from his pelvis. As Alistair Horne pointed out: "Because of the length of time it had taken to get him to proper medical care, combined with the primitiveness and lack of modern drugs in First World War hospitals, the wound closed up before being drained of all infection. Abscesses formed inside, poisoning his whole system."

Macmillan was returned to England and for a while his life seemed to be in danger. His mother arranged for him to be transferred to a private hospital in Belgrave Square. Later Macmillan claimed that "my life was saved by my mother's action. The pain was so bad that over the next two years he had to submit to anesthetic each time his dressings were changed.

After the Armistice, Macmillan joined the family publishing company. He took a keen interest in politics and for a while he was tempted to join the Liberal Party. However, he calculated that the party was in decline and decided instead to join the Conservative Party. In the 1924 General Election he became the Conservative MP for Stockton-on-Tees. Defeated in the 1929 General Election he returned in to the House of Commons in 1931.

On this day in 1898 Bertolt Brecht was born in Augsburg, Germany. His father was a respected and well-to-do citizen, the managing director of a paper mill, his mother the daughter of a civil servant. "He was a sensitive and taciturn child, non-conformist and rebellious in a quiet, negative way."

Brecht later wrote: "I grew up as the son of well-to-do people. My parents put a collar round my neck and taught me the habit of being waited on and the art of giving orders. But when I had grown up and looked around me I did not like the people of my class. And I left my own class and joined the common people."

Always a rebel, Brecht maintained that he had learned more from opposition than emulation at school. "Elementary school bored me for four years. During my nine years at the Augsburg Realgymnasium (Grammar School) I did not succeed in imparting any worthwhile education to my teachers. My sense of leisure and independence was tirelessly fostered by them... By indulgence in all kinds of sport I acquired some heart trouble which introduced me to the mysteries of metaphysics."

In 1916 he left school and studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Munich. However, after a few terms he had to interrupt his studies when he was called up into the German Army to take part in the First World War. As he was a medical orderly in a military hospital. He told Sergei Tretyakov: "I was mobilized in the war and placed in a hospital. I dressed wounds, applied iodine, gave enemas, performed blood-transfusions. If the doctor ordered me: 'Amputate a leg, Brecht!' I would answer: 'Yes, Your Excellency!' and cut off the leg. If I was told: 'Make a trepanning!' I opened the man's skull and tinkered with his brains. I saw how they patched people up in order to ship them back to the front as soon as possible."

Brecht later wrote a poem about his experiences, entitled Legend of a Dead Soldier: "They poured some brandy down his throat/The rotten corpse to rouse/Two hefty nurses grabbed his arms/And his half-naked spouse/Because the rotten body stank/A parson limped ahead/And over him his incense swung/To cover the stench of the dead/The band in the van with rum-tum-tum/Played him a rousing march/The soldier as he had been drilled/Kicked his legs high from his arse."

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany.

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks."

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Brecht was whole-heartedly on the side of the revolutionaries and took part in the rebellion in Augsburg: "I was... twenty when I saw the reflection of the great fire (of the Russian Revolution) in my own home town. I was a medical orderly in an Augsburg military hospital. The barracks and even the military hospitals emptied, the ancient city suddenly filled up with new people, who came in large numbers from the outskirts."

Brecht later explained: "I was a member of the Augsburg Revolutionary Committee. The hospital was the only military unit in the town. It elected me... We did not boast a single Red Guardsman. We didn't have time to issue a single decree or to nationalize a single bank or to close a single church. After two days General Epp's troops came to town on their way to Munich. One of the members of the revolutionary committee hid at my house until he managed to escape."

Brecht wrote a play and took it to show the left-wing writer and theatre critic, Lion Feuchtwanger. The play that eventually became known as Drums in the Night. "Shortly after the outbreak of the so-called German Revolution, a very young man came to my Munich apartment, thin, badly shaved, and unkempt in appearance. He slunk around the walls, spoke Swabian dialect, had written a play, and was called Bertolt Brecht. The play was called Spartakus. Unlike most young authors, who on handing over their manuscripts have a habit of pointing to their bleeding hearts from which their work has been torn, this young man stressed that he had written his play Spartakus exclusively to make money."

The play was about a member of the Spartacus League who after becoming a member of the German Army during the First World War, had taken part in the failed German Revolution. Feuchtwanger was impressed with the play but upset Brecht. "I telephoned the unkempt young man and asked him why he had lied to me; he could not possibly have written this play merely out of material necessity. At this the young author became very violent and dialectical almost to the point of incoherence and declared that he had indeed written this play for money's sake only; but that he had another play as well, which was really good and he would bring it to me. He brought it. It was called Baal... and turned out to be an even wilder, even more extravagant and very splendid piece of work."

Brecht also wrote songs about his war experiences and his socialist beliefs. He sung them in taverns and coffee houses, accompanying himself on the guitar or banjo and bawling out the verse in his high-pitched voice. Sometimes, ex-soldiers in the audience, who still had patriotic sympathies, took exception at the sentiments expressed in these ballads and gave him a good beating at the end of the session.

Although he was disliked by the men the women loved him: "Brecht... was always unshaven. But the way he made his hair grow over his forehead had a kind of naive coquettishness. He smelt like soldiers on the march. Nor did his angular, malicious sense of humour seem the right thing for the ladies. There was an unmistakable odour of revolution about him. Clearly it was his way of singing his crude ballads that did it. When he sang them with his shrill voice women swooned."

Another friend, George Grosz, commented: "He (Brecht) dressed like nobody else in the circle, and looked like some kind of engineer or car mechanic, always wearing a thin leather tie - without oil stains, of course. Instead of the usual sort of waistcoat, he wore one with long sleeves; the cut of all his suits were baggy and somewhat American, with padded shoulders and wedge-shaped trousers. Without his monkish face and the hair combed down on his forehead he might have been mistaken for a cross between a German chauffeur and a Russian commissar."

After the encouragement of Feuchtwanger, Brecht concentrated on the revision of Bael, a story that concerns a young man who becomes involved in several sexual affairs and at least one murder. He had a routine of writing from six in the morning till midday. He used to read his new version of the play to his friends. According to Hanns Otto Münsterer: "Large sections of the first part have been cut, especially the newspaper office scenes, in which Bael reaches out for an orderly life, so the overall effect is now more anarchic and anti-bourgeois."

In October 1919, Brecht began to act as theatre critic for the newspaper owned by the left-wing Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). His notices were distinguished mainly by their rudeness: "The man who has leased the Augsburg Municipal Theatre as his milch-cow knows today, after so many years, about as much about literature as an engine driver knows about geography."

Brecht also became friends with Arnolt Bronnen, who worked as a clerk but wanted to become a novelist. He later described how he first met him at the apartment of the journalist, Otto Zarek."From one of the rooms I could hear guitar music... I went in. It was rather dark there; at first I could only hear a croaking voice... Then I saw the singer: an emaciated young man of twenty-four with steel-rimmed glasses and untidy dark hair that fell over his forehead. I stared at him. I was as if under a spell. I experienced a sensation which perhaps is only given to very lonely human beings: to be suddenly confronted with man in all the richness of his being. He sang, he spoke, he read aloud, there were four other young people in the room; I did not see them. I only stared at this one young man."

Brecht's play Bael, had its first stage performance in Leipzig. It did not have very good reviews with the theatre critic of Leipziger Neueste Nachrichten, called the play a "mud bath" and added: "It would have been wiser and in better taste if the municipal theatre had left this boy's tour-de-force to people to read this kind of thing and had spared us, Brecht, and itself this wild evening."

The first performance of Drums in the Night took place on 29th September, 1922. Brecht asked the influential Berlin critic Herbert Ihering to come to Munich for the first night: "I know exactly how much I am asking, but very much indeed depends on it for me. Since Berlin has ceased to make experiments, it has become extremely difficult to obtain decent criticism at a time when one needs it most."

Ihering was impressed with the play: "The twenty-four-year-old poet Bert Brecht has changed the literary physiognomy of Germany overnight. With Bert Brecht a new tone, a new melody, a new vision has entered our time... Brecht is impregnated with the horror of this age in his nerves, in his blood. This horror creates a pallid atmosphere, a half-light round men and things... Brecht physically feels the chaos and putrid decay of the times. Hence the unparalleled force of his images. This language can be felt on the tongue, on the palate, in one's ears, in one's spine... It is brutally sensuous and melancholically tender. It contains malice and bottomless sadness, grim wit and plaintive lyricism."

In 1922 Brecht was awarded the Kleist Prize, an annual award to the best young dramatic talent in Germany. Arnolt Bronnen claimed that Brecht had an unusual way of writing: "Comfortably puffing his cigar Brecht stalked through the room listening to arguments and counter-arguments from dozens of people, cracked jokes, but stuck unshakably to his main line of work. He rode his thought until, magnificently formulated, he could dictate it to the miniature audience of his ever-present aides."

On this day in 1901 Stella Adler was born in New York. She joined the Group Theatre was formed in New York by Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg in 1931. Others involved in the group included Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, Franchot Tone, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

Adler, who later married Harold Clurman, played leading roles in Gentle Woman(John Howard Lawson) and Awake and Sing! and Paradise Lost (Clifford Odets).

While working with the group Lee Strasberg developed what became known as the Method. Based on the ideas of the Russian director, Konstantin Stanislavsky, it was a system of training and rehearsal for actors which bases a performance upon inner emotional experience, discovered largely through the medium of improvisation. Adler was influenced by Strasberg's approach to acting and this can be seen in her performances in the films, Love on Toast (1938), Shadow of the Thin Man (1941) and My Girl Tisa (1948).

After the Second World War, most of the members of the group were investigated by House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Some like Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb testified and named other members of left-wing groups in the 1930s. Those that refused to do this such as Stella Adler, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, John Randolph, and Joseph Bromberg were blacklisted.

Unable to find work in the cinema and on television, Adler became primarily a teacher of other actors. Whereas Lee Strasberg placed an emphasis on self, Adler urged students to transcend their own experiences and by investigating the play's circumstances rather than their own. Her students included Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Warren Beatty and Harvey Keitel.

Stella Adler died in Los Angeles, California on 21st December, 1992.

On this day in 1903 Abel Meeropol was born into a Jewish family. After leaving college he became a teacher in New York City. His students included Paddy Chayefsky, Neil Simon and James Baldwin. Meeropol was also a member of the American Communist Party.

Meeropol was also a writer and worried about anti-semitism and chose to publish his poem under the pseudonym "Lewis Allan", the first names of his two stillborn children.

In 1937 Meeropol saw a photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. Meeropol later recalled how the photograph "haunted me for days" and inspired the writing of the poem, Strange Fruit. The poem was published the poem in the New York Teacher and later, the Marxist journal, New Masses.

After seeing Billie Holiday perform at the club, Café Society, in New York City, Meeropol showed her the poem. Holiday liked it and after working on it with Sonny White turned the poem into the song, Strange Fruit. The record made it to No. 16 on the charts in July 1939. However, the song was denounced by Time Magazine as "a prime piece of musical propaganda" for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg were executed on 19th June, 1953. As Joanna Moorhead pointed out: "From the time of their parents' arrests, and even after the execution, they (Rosenberg's two sons) were passed from one home to another - first one grandmother looked after them, then another, then friends. For a brief spell, they were even sent to a shelter. It seems hard for us to understand, but the paranoia of the McCarthy era was such that many people - even family members - were terrified of being connected with the Rosenberg children, and many people who might have cared for them were too afraid to do so."

Abel Meeropol and his wife Anne, eventually agreed to adopt Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg. According to Robert: "Abel didn't get any work as a writer throughout most of the 1950s... I can't say he was blacklisted, but it definitely looks as though he was at least greylisted." Both boys later changed their name to Meeropol.

Meeropol taught at the De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx for 27 years, but continued to write songs, including the Frank Sinatra hit, The House I Live In and Apples, Peaches and Cherries that was successfully recorded by Peggy Lee. A French version of this song, Scoubidou, was a number one hit in France for Sacha Distel.

Abel Meeropol died on 30th October, 1986, at the Jewish Nursing Home in Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

On this day in 1907 William Howard Russell died. Russell was born in Tallaght, Ireland, on 28th March 1820. His father, John Russell (1796–1867) was a Protestant and his mother, Mary Kelly (1803–1840), a Roman Catholic. In the early years of William's life his father's business failed and he moved to Liverpool.

Russell was educated at private schools in Dublin. As a fifteen year old he attempted unsuccessfully to join the army. In October 1838 he entered Trinity College. Although an able student he left in 1841 without a degree in order to work for his cousin, Robert Russell, a journalist reporting on the Irish General Election. Later that year he moved to London.

In 1842 Russell became a teacher of mathematics at Kensington Grammar School. He also did some freelance writing for The Times. The editor, John Thadeus Delane, was impressed by his work that by 1843 he was employed full-time by the newspaper. This included reporting the trial of Daniel O'Connell for sedition. He also covered the subject of Railway Mania.

In 1845 he joined the staff of The Morning Chronicle. Russell held conservative political views and in April 1848, he enrolled as a special constable against the Chartists. Later that year he rejoined The Times. According to his biographer, Roger T. Stearn: "In June 1850 he was called to the bar at the Middle Temple, but never applied himself enough to succeed, though it was some years before he ceased to take an occasional brief. In 1850 he accompanied the Schleswig-Holstein forces in their campaign against the Danes and was present at the decisive Danish victory of Idstedt (25 July). Convivial and amusing company, Billy Russell spent much time at clubs, especially the Garrick, and enjoyed brandy, billiards, and whist." He also became friends with Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray and Douglas Jerrold.

John Thadeus Delane, sent Russell to cover the Crimean War. He left London on 23rd February 1854. After spending time with the army in Gallipoli and Varna, he reported the battles and the Siege of Sevastopol. He found Lord Raglan uncooperative and wrote to Delane alleging unfairly that "Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army".

Roger T. Stearn has argued: "Unwelcomed and obstructed by Lord Raglan, senior officers (except de Lacy Evans), and staff, yet neither banned, controlled, nor censored, Russell made friends with junior officers, and from them and other ranks, and by observation, gained his information. He wore quasi-military clothes and was armed, but did not fight. He was not a great writer but his reports were vivid, dramatic, interesting, and convincing.... His reports identified with the British forces and praised British heroism. He exposed logistic and medical bungling and failure, and the suffering of the troops."

His reports revealled the sufferings of the British Army during the winter of 1854-1855. These accounts upset Queen Victoria who described them as these "infamous attacks against the army which have disgraced our newspapers". Prince Albert, who took a keen interest in military matters, commented that "the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country." Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed military information potentially useful to the enemy.

Russell reported that British soldiers began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. When Mary Seacole heard about the cholera epidemic she travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When Russell publicised the fact that a large number of soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale volunteered her services and was eventually given permission to take a group of thirty-eight nurses to Turkey.

Russell's reports led to attacks on the government by the the Liberal M.P. John Roebuck. He claimed that the British contingent had 23,000 men unfit for duty due to ill health and only 9,000 fit for duty. When Roebuck proposal for an inquiry into the condition of the British Army, the government was passed by 305 to 148. As a result the Earl of Aberdeen, resigned in January 1855. The Duke of Newcastle told Russell " It was you who turned out the government".

When he arrived back in England he was treated like a national hero. In 1856 Trinity College awarded him an honorary degree. On the advice of Charles Dickens he went on a very financially successful lecture tour on the Crimean War. It is estimated that during this period he received £1,600 for his talks. Russell also published The War: from the Landing at Gallipoli to the Death of Lord Raglan (1856). This was followed by a series of books on military matters.

In December 1857 John Thadeus Delane sent Russell to report on the Indian Mutiny and to investigate rebel atrocities. Roger T. Stearn points out: "Russell... accompanied Sir Colin Campbell (Lord Clyde), who welcomed and assisted him, on the 1858 campaign, and narrowly escaped being killed by a rebel. Russell criticized British snobbery as well as attitudes to and treatment of Indians, and advocated leniency and conciliation. His Times articles were attacked by the Anglo-Indian press. Delane attributed the cessation of indiscriminate executions to Russell's first report from Cawnpore."

In 1861, The Times sent Russell to cover the American Civil War. He was paid the amazing sum of £1,200 a year and expenses. He opposed slavery and supported the Union Army. However, his criticism of their tactics at Bull Run he was forbidden to accompany the army. He returned to England in April 1862. He retired in 1863 and received a pension of £300 a year from the newspaper. However he continued to work for them on a freelance basis. This included the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). As private secretary to Prince of Wales (later George V), he went to South Africa in 1879.

Throughout this period he edited and owned the Army and Navy Gazette. In the newspaper he advocated army reforms, breech-loading artillery, and conscription. He also worked as a freelance writer for the Daily Telegraph. He was considered the best reporter in England and could command very high fees for his work. On the recommendation of Lord Rosebery he was knighted in 1895.

Roger T. Stearn has argued: "He was about 5 feet 7 inches, portly, with blue eyes. He had a pleasant baritone and retained his Irish brogue. In the Crimea and India he was bearded, later only moustached. Latterly he was overweight. Sociable, affectionate, charming, lively, amusing, and a raconteur... He was brave, impulsive, moved by indignation and pity, and sometimes outspoken. However, he was sometimes careless, unfair, and - as apparently with Raglan - motivated by a personal grudge. He continued to spend much time at his clubs, which included the Carlton and the Marlborough, and he ate and drank much. Despite his post-Crimea substantial income, he spent extravagantly and was repeatedly in debt."

Stearn adds: "Though only a small minority of his working life was spent reporting wars, Russell's greatest achievement was as a war correspondent, a term he disliked. Though not the first person to report a war for a newspaper, in the Crimea he established the concept and credibility of the war correspondent and strong public support for the role. Largely because of him war correspondence emerged as a new branch of journalism, and he largely set the pattern for British war correspondents."

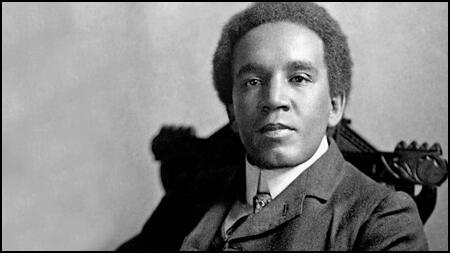

On this day in 1912 Samuel Coleridge Taylor wrote a letter about racism to the Croydon Guardian. "It is amazing that grown-up, and presumably educated people, can listen to such primitive and ignorant nonsense-mongers, who are men without vision, utterly incapable of penetrating beneath the surface of things There is an appalling amount of ignorance amongst English people regarding the Negro and his doings. Personally, I consider myself the equal of any white man who ever lived, and no one could change me in that respect; on the other hand, no man reverences worth more than I, irrespective of colour and creed. May I further remind the lecturer that really great people always see the best in others; it is the little man who looks for the worst - and finds it. It was an arrogant 'little' white man who dared to say to the great Dumas, 'and I hear you actually have negro blood in you!' 'Yes', said the witty writer; 'My father was a Mulatto, his father a Negro, and his father a monkey. My ancestry begins where yours ends!' Somehow I always manage to remember that wonderful answer when I meet a certain type of white man (a type, thank goodness! as far removed from the best as the Poles from each other) and the remembrance makes me feel quite happy- wickedly happy, in fact!'

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was born in Holban, London, on 15th August, 1875. His father, Daniel Taylor, came to England from Sierra Leone to study medicine. After graduating he found his race was a barrier to maintaining a medical practice in England. He therefore decided to return to Sierra Leone, soon after Samuel was born.

Samuel was raised by his mother, Alice Taylor. Named after the poet Samuel Coleridge, he took a keen interest in music and at the age of 15 applied to enter the Royal College of Music (RCM). Sir George Grove, the principal of the RCM, originally said no as he feared other students might complain about having to study with a black man.

In 1896 he met Paul Laurence Dunbar. The son of a former slave, Dunbar had written a great deal of poetry about Africa. He decided to set some of Dunbar's poems to music and African Romances was published in 1897.

Edward Elgar, Britain's leading composer, was very impressed with Samuel Coleridge Taylor's work. He wrote that he was "far and away the cleverest fellow amongst the young men" in the country. This was reinforced by the first performance of Hiawatha's Wedding Feast (1899). It was an immediate success and for the next ten years was the country's most popular English choral-orchestral work. This was followed by Ethiopia Saluting the Colours (1902), Four African Dances (1902) and Twenty-Four Negro Melodies (1904).

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was a leading exponent of Pan-Africanism, which emphasized the importance of a shared African heritage. Along with his friend Duse Mohammed, he founded The African and Orient Review, a Pan-Africanist newspaper in London. In 1904 he wrote about his work Twenty-Four Negro Melodies: "What Brahms has done for the Hungarian folk music, Dvorak for the Bohemian, and Grieg for the Norwegian, I have tried to do for these Negro Melodies."

While living in Croydon he experienced a great deal of racial prejudice. Samuel Coleridge Taylor's white wife (Jessie Walmisley) was also a target of abuse when she was out walking with her husband. His daughter later reported that gangs of local youths would often make comments about the colour of his skin: "When he saw them approaching along the street he held my hand more tightly, gripping it until it almost hurt."

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was unable to survive on his royalties and in 1903 he became professor of composition at Trinity College of Music in London. He also worked as a conductor and several times toured the United States. After reading The Souls of Black Folk by William Du Bois he took a keen interest in politics. While in America he met and had discussions with Booker T. Washington and Theodore Roosevelt. In 1906 he gave concerts in several cities including New York, Boston, St Louis, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Washington and Chicago.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor died of pneumonia on 1st September, 1912. His two children, Hiawatha and Avril, both had distinguished careers as composers and conductors.

On this day in 1914 Larry Adler was born in Baltimore. A self-taught musician, he won the Maryland Harmonica Championship at the age of 13 and began his show business career the following year.

He appeared in Sky High (1931), Many Happy Returns (1934), The Big Broadcast (1936), The Singing Marine (1937) and Sidewalks of London (1938). He also toured the USA, Europe, Africa and the Middle East. In 1938 he married Eileen Walser and the couple had three children. In the 1940s Adler played as a soloist with some of the world's leading symphony orchestras.

Adler was particularly liked for his renditions of George Gershwin. His friend, John Calder, has pointed out: "Adler... moved in jazz, modern music and Broadway musical circles, and he was adapting a wide variety of musical scores for his own instrument, as well as composing for it himself. He performed as a soloist with an orchestra in Sydney in 1939 as part of an Australian tour, and thereafter toured the world, either as an individual performer, his playing being interspersed with jokes, chats and anecdotes, or as part of a larger show."

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate people with left-wing views in the entertainment industry. In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organizations before the war but had not so far been blacklisted. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of The Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party.

A free copy of Red Channels was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. Adler was one of those named and after refusing to appear before the HUAC. Adler said, "The only way to get off that blacklist was to go before the committee and shop your friends. There was no way I was going to do that."

Adler moved to England where he wrote the music for films such as Genevieve (1953), The Hook (1963), King and Country (1964) and A High Wind in Jamaica (1965). Humphrey Lyttleton commented: "He made wonderful music, you just can't get away from it, the sound he got out of the harmonica was as great as Yehudi Menuhin could get from a violin. He could express himself equally well in pop, jazz or classical music."

In 1969 Adler married Sally Cline. The couple had one daughter but the marriage was dissolved in 1977. In his later years Adler also worked as a journalist and was food critic for Harper's & Queen. Books by Adler included It Ain't Necessarily So (1985) and Me and My Big Mouth (1994).

John Calder has commented: "It has often been asked why he did not bring his musicianship to a more conventional instrument, but he was not interested in being just a musician. He enjoyed entertaining an audience and his sense of timing when relating a story on stage made him a stand-up comic and raconteur of considerable charisma. During the last 30 years he had spent much time in night-clubs and small theatres and with a one-man show that employed all his talents."

Larry Adler died in London on 6th August 2001.

On this day in 1966 Mary Hamilton died.

Mary Hamilton, the daughter of Robert Adamson and Daisy Duncan, was born on 8th July 1882. Robert Adamson came from a poor, working-class family, but he eventually became Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at Glasgow University. Mary's mother came from a Quaker family and had been one of the first women to become a student at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Robert and Daisy Adamson were both supporters of women's rights and were determined to raise their six children according to these principals. When Mary, the eldest daughter, had reached the age of eighteen, she was sent to Newnham College. At university she became friendly with Margery Corbett and together they joined the Cambridge branch of the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Mary spent many weekends at Margery's home in Danehill, Sussex, and was brought into contact with Marie Corbett, Cicely Corbett, and other committed feminists in Sussex.

Mary obtained a first class honours degree, and this enabled her to obtain a teaching post in the history department of the University College of South Wales. In 1905 she resigned her post after her marriage to a university colleague, Charles Hamilton.

Mary remained an active member of the NUWSS and after her conversion to socialism, she joined the Independent Labour Party. On the outbreak of the First World War, she joined the Union for Democratic Control and became active in the struggle for a negotiated peace.

In 1920 Lady Margaret Rhondda, founded the political magazine Time and Tide. Mary became one of the journal's main contributors. She also worked as a journalist for The Economist magazine and edited Review of Reviews with Philip Gibbs.

In 1923 General Election Mary Hamilton made her first attempt to enter House of Commons. After the passing of the Equal Franchise Act in 1928, which gave all women over the age of twenty-one the vote, it became easier for women to be selected as candidates in winnable constituencies.

In the 1929 General Election Hamilton became Labour MP for Blackburn. Mary Hamilton was appointed as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Clement Attlee, the Postmaster General in the Ramsey MacDonad government. Mary also served on the Royal Commission on the Civil Service where she argued strongly in favour of equal pay for men and women. Mary also became involved in the campaign to remove the marriage bar on women teachers.

Mary Hamilton, strongly opposed to the decision by Ramsay MacDonald to form a National Government. "But greatly as I admire your courage, and ready as I am to believe your gesture may have saved us all, I could not, as I thought the whole situation out on my long journey home, find it possible to support this Government or believe in its policy. It is a very hard decision to make; and this afternoon's party meeting does not make it agreeable to act on - but, there it is. I felt I must write this line to express the deep regret I feel about this, temporary severance between you and the party."

After her defeat in the 1931 General Election, Hamilton remained in public life. Mary was a governor of the BBC (1932-1936) and a member of the London County Council (1937-1940).

During the Second World War Hamilton was head of the American Division of the Ministry of Information. Hamilton also wrote biographies of important labour figures such as Margaret Bondfield and Arthur Henderson.

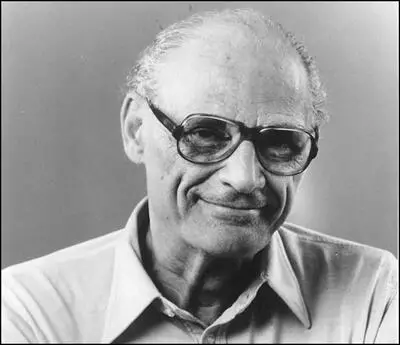

On this day in 2005 Arthur Miller died aged 89, at his home in Roxbury, Litchfield County. Miller, the son of Isidore Miller and Augusta Barnett Miller, was born in New York City on 17th October, 1915. His father was involved in the Manhattan rag trade. The family moved from Harlem to Brooklyn when Arthur was a child.

Isidore Miller's business was destroyed as a result of the Wall Street Crash. The theatre critic, Michael Ratcliffe: "This first great discord of the American century informs all his work. Like Dickens and Ibsen, he drew from his father's financial disaster the lifelong convictions that catastrophe could strike without warning and that the crust of civilised order was perilously thin."

Miller worked in a warehouse after graduating from high school. When he saved enough money he attended the University of Michigan, where he began writing plays. One of these won a $1,250 prize from the Bureau of New Plays run by the New York producers, the Theater Guild. After graduating in 1938 he joined the Federal Theater Project (FTP). As he explained in his biography, Timebends - A Life (1987): "To join the WPA Theatre Project it was necessary to get on the welfare rolls first, in effect to be homeless and all but penniless... and conniving to get myself a twenty-three-dollar-a-week job."

The project was established by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935 as part of the New Deal attempt to combat the Depression. The FTP was an attempt to offer work to theatrical professionals. Harry Hopkins, hoped it would also provide "free, adult, uncensored theatre". Elmer Rice was placed in charge of the FTP in New York City. In 1936 alone, the FTP employed 5,385 people in the city. Over a three year period over 12 million people attended performances in the city.

In 1939 Miller was offered a contract with Twentieth Century Fox: "My purity was still breathtakingly unmarred through the thirties, so much so that... with the Federal Theatre Project, which was already coming to its end, I had no qualms about turning down a two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar-a-week offer by a Colonel Joy, representing Twentieth Century Fox, to come to work for them."

Arthur Miller held left-wing opinions and was horrified by the views expressed by Charles E. Coughlin on the radio. "Father Charles E. Coughlin, who by 1940 was confiding to his ten million Depression-battered listeners that the president was a liar controlled by both the Jewish bankers and, astonishingly enough, the Jewish Communists, the same tribe that twenty years earlier had engineered the Russian Revolution... He was arguing... that Hitlerism was the German nation's innocently defensive response to the threat of Communism, that Hitler was only against 'bad Jews', especially those born outside Germany."

A college football injury kept him from active service in the Second World War. In 1941 he began work on his play, The Man Who Had All the Luck. It became his first professionally produced play when it arrived on Broadway in November 1944. Miller claimed that "it managed to baffle all but two of the critics (New York had seven daily newspapers then, each with its theatre reviewer)." Directed by Joseph Fields, it opened at the Forrest Theatre, where it ran for only 4 performances.

Miller's next play was All My Sons. Opening at the Coronet Theatre on 29th January, 1947, directed by Elia Kazan, and starring Ed Begley, Karl Malden and Arthur Kennedy. As Michael Ratcliffe pointed out: "A family tale of corrupt profiteering at home that led to the death of US pilots abroad, it exploded in the pause between victory and the attempted press-ganging of show business for Washington's cold war. From this point on, Miller's best scenes display a mastery of conversation, a gift for sketching vivid characters on the margins of a play, and a narrative talent for seizing the spectator's attention from the start." The play won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award and ran for 328 performances.

His next play, Death Of A Salesman, was sent to Elia Kazan. He thought it was "a great play" and that the character of Willy Loman reminded him of his father. Miller later recalled that Kazan was the "first of a great many men - and women - who would tell me that Willy was their father." The play opened at the Morosco Theatre on 10th February, 1949. It was directed by Kazan and featured Lee J. Cobb (Willy Loman), Mildred Dunnock (Linda), Arthur Kennedy (Biff) and Cameron Mitchell (Happy).

Death Of A Salesman played for 742 performances and won the Tony Award for best play, supporting actor, author, producer and director. It also won the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play. Miller was himself highly critical of the play: "I knew nothing of Brecht then or of any other theory of theatrical distancing: I simply felt that there was too much identification with Willy, too much weeping, and that the play's ironies were being dimmed out by all this empathy."

Miller broke with Elia Kazan over his decision to give names of former members of the American Communist Party to the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Miller was himself blacklisted by Hollywood when he refused to testify in front of the HUAC. However, this did not stop his plays being performed on stage as Broadway refused to impose a blacklist.

Miller was distressed by the sight of former friends giving evidence against other former friends as a result of McCarthyism. He decided to write a play about this situation: "What I sought was a metaphor, an image that would spring out of the heart, all-inclusive, full of light, a sonorous instrument whose reverberations would penetrate to the centre of this miasma."

During this period Miller read The Devil in Massachusetts (1949), a book about the 1692 Salem Witch Trials by Marion Lena Starkey. The book included the previously unpublished verbatim transcriptions of documents and papers on witchcraft in Salem. Miller later recalled: "At first I rejected the idea of a play on the subject.... But gradually, over weeks, a living connection between myself and Salem, and between Salem and Washington, was made in my mind - for whatever else they might be, I saw that the hearings in Washington were profoundly and even avowedly ritualistic. After all, in almost every case the Committee knew in advance what they wanted the witness to give them: the names of his comrades in the Party. The FBI had long since infiltrated the Party, and informers had long ago identified the participants in various meetings. The main point of the hearings, precisely as in seventeenth-century Salem, was that the accused make public confession, damn his confederates as well as his Devil master, and guarantee his sterling new allegiance by breaking disgusting old vows - whereupon he was let loose to rejoin the society of extremely decent people."

The Crucible was first performed at the Martin Beck Theater on Broadway on 22nd January, 1953. The cast included Arthur Kennedy (John Proctor), Walter Hampden (Deputy-Governor Danforth), Beatrice Straight (Elizabeth Proctor), E. G. Marshall (Reverend Hale), Jean Adair (Rebecca Nurse), Joseph Sweeney (Giles Corey) and Madeleine Sherwood (Abigail Williams).

The play was not well received by the critics. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Timebends - A Life (1987): "I have never been surprised by the New York reception of a play... What I had not quite bargained for, however, was the hostility in the New York audience as the theme of the play was revealed; an invisible sheet of ice formed over their heads, thick enough to skate on. In the lobby at the end, people with whom I had some fairly close professional acquaintanceships passed me by as though I were invisible." Even so, the production won the Tony Award for best play of 1953.

Miller's next two plays, A View from the Bridge and A Memory of Two Mondays, were badly received. It is believed that this reaction was mainly due to political reasons. During this period Miller left his first wife Mary Slattery and on 25th June, 1956 married the actress Marilyn Monroe.

In 1956 Miller was called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Miller refused to testy, saying "I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him." In May 1957 he was found guilty of contempt of Congress, sentenced to a $500 fine or thirty days in prison, blacklisted, and had his passport withdrawn.

After the Hollywood Blacklist was lifted in 1960, Miller wrote the screenplay for the movie, The Misfits (1961). The film starred his wife but later that year they were divorced. 19 months later, Marilyn Monroe died of an apparent drug overdose. After her death Miller married Inge Morath.

Miller's next play was After the Fall. Starring Barbara Loden, Jason Robards Jr. and Faye Dunaway it opened on 23rd January, 1964 at the Anta Theatre on Washington Square. It appeared to be based on his relationship with Monroe. He later admitted that everything he had written was based on somebody he had seen or known. However, the critics thought it was wrong of him to write about his marriage to a woman who had committed suicide. His next two plays, Incident at Vichy (1964) and The Price (1968), saw a return to form.

Other plays by Arthur Miller included: The Creation of the World and Other Business (1972), The Archbishop's Ceiling (1977) and The American Clock (1980). Miller also wrote an impressive autobiography, Timebends - A Life (1987). Miller continued to write plays and the best of these include The Last Yankee (1991), The Ride Down Mt. Morgan (1991), Broken Glass (1994), Mr Peter’s Connections (1998), Resurrection Blues (2002) and Finishing the Picture (2004), a return to the subject of Marilyn Monroe.

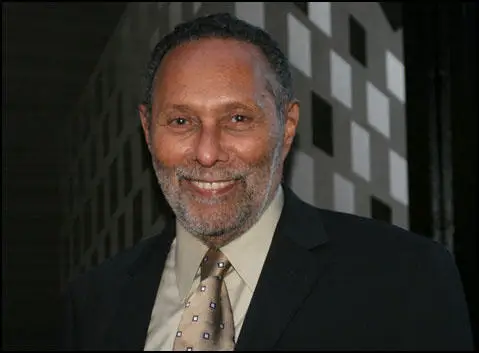

On this day in 2014 Stuart Hall died. Hall was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1932. He later recalled: "We were part Scottish, part African, part Portuguese-Jew." His father, Herman Hall, was the first non-white person to hold a senior position – chief accountant – with United Fruit Company in the country. He was educated at Jamaica College and after he won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University he moved to England in 1951.

While studying English at Merton College he developed radical political views. Hall found he was in a small minority: "In the 1950s universities were not, as they later became, centres of revolutionary activity. A minority of privileged left-wing students, debating consumer capitalism and the embourgeoisement of working-class culture amidst the 'dreaming spires', may seem, in retrospect, a pretty marginal political phenomenon... I began not as somebody formed but as somebody troubled... I thought I might find the real me in Oxford. Civil rights made me accept being a black intellectual."

Hall considered himself as a Marxist but as an opponent of the policies of Joseph Stalin he did not join the Communist Party. Instead he became a member of what became known as the New Left. His political views were based on his reading of history: "Britain is not homogenous; it was never a society without conflict. The English fought tooth and nail over everything we know of as English political virtues – rule of law, free speech, the franchise."

Hall became a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Other members included J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, E. P. Thompson, Fenner Brockway, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, Frank Cousins, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot. At one CND march from Aldermaston to London, Hall met his future wife, Catherine Barrett. They had two children, Becky and Jess.

In 1957 Hall joined with E. P. Thompson, Raphael Samuel, Raymond Williams, Ralph Miliband and John Saville to launch two radical journals, The New Reasoner and the New Left Review, where he was the founding editor. Hall also worked as a supply teacher in Brixton and in 1961, he became a lecturer in film and media at Chelsea College. He published his first book, The Popular Arts, co-authored with Paddy Whannel, in 1964. This resulted in him being invited by Richard Hoggart to join the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham.

In 1968 Hall became director of the CCCS unit. Over the next few years he wrote several books including Situating Marx: Evaluations and Departures (1972), Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse (1973), Reading of Marx's 1857 Introduction to the Grundrise (1973) and Policing the Crisis (1978). As the Guardian pointed out: "The foundations of cultural studies lay in an insistence on taking popular, low-status cultural forms seriously and tracing the interweaving threads of culture, power and politics. Its interdisciplinary perspectives drew on literary theory, linguistics and cultural anthropology in order to analyse subjects as diverse as youth sub-cultures, popular media and gendered and ethnic identities... Hall was always among the first to identify key questions of the age, and routinely sceptical about easy answers. A spellbinding orator and a teacher of enormous influence, he never indulged in academic point-scoring. Hall's political imagination combined vitality and subtlety; in the field of ideas he was tough, ready to combat positions he believed to be politically dangerous. Yet he was unfailingly courteous, generous towards students, activists, artists and visitors from across the globe, many of whom came to love him."

Hall argued that Britain experienced a real revolution in the 1960s: "Remember 1968, when everyone said that nothing changed, that nobody won state power. It’s true. The students didn’t win. But since then life has been profoundly transformed. Ideas of communitarianism, ideas of the collective, of feminism, of being gay, were all transformed by the impact of a revolution that did not succeed… So I don’t believe in judging the historical significance of events in terms of our usually faulty judgment of where they may end up.”

In 1979 Hall was appointed as professor of sociology at the Open University. The university's current Vice-Chancellor, Martin Bean, has pointed out that he was a great success: "Stuart was one of the intellectual founders of cultural studies, publishing many influential books and shaping the conversations of the time. It was a privilege to have Stuart at the heart of The Open University – touching and influencing so many lives through his courses and tutoring. He was a committed and influential public intellectual of the new left, who embodied the spirit of what the OU has always stood for: openness, accessibility, a champion for social justice and of the power of education to bring positive change in peoples' lives."

It was Hall who first used the term "Thatcherism" in an article that appeared in Marxism Today in January 1979, to describe the political influence of Margaret Thatcher. As The Daily Telegraph pointed out: "The Conservative leader had been patronised by many on the Left as little more than a shrill housewife. Hall was one of the first to acknowledge that Britain was entering a new era of politics. He characterised the phenomenon of Thatcherism as something more significant and more insidious than the personal style of one politician... To Hall, Thatcherism’s popularity originated in errors on the Left. Socialists, he argued, had failed to recognise the disillusionment of many working class people with the bureaucratic state, while British trade unions, although industrially strong, had not offered any alternative vision.... Hall called for the Left to fight the cultural battle against Thatcherism by an engagement with new social movements such as multiculturalism, environmentalism and gay rights."

The editor, Martin Jacques, pointed out that this was the beginning of a long-term relationship. "For the next decade, it felt as if we lived in each other's pockets. The way in which Stuart wrote was fascinating. Some, like Eric Hobsbawm, the other Marxism Today great, produced a perfect text first time out. Stuart's first draft, in contrast, would arrive in an extremely incoherent and rambling form, as if trying to clear his throat. Over the next 10 days, one draft would follow another, in quick succession, like a game of ping-pong. His was a restless, inventive intellect, always pushing the envelope, at his best when working in some form of collaboration with others. His end result was always worth savouring, his articles hugely influential."

Other books by Hall include The Hard Road to Renewal (1988), Resistance Through Rituals (1989), Modernity and Its Future (1992), The Formation of Modernity (1992), Questions of Cultural Identity (1996), Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (1997) and Visual Cultural (1999). Professor Henry Louis Gates of Harvard University called him "Black Britain's leading theorist of black Britain."

Hall retired from the Open University in 1997 and became a member of the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, that had been established by the Runnymede Trust. He remained active in politics and was a leading critic of Tony Blair and attacked him for occupying the “terrain defined by Thatcherism”. He later described Blair as "the greatest Tory since Margaret Thatcher” and argued that even though the leadership of the Conservative Party were “divided, exhausted and demoralised,” it was still “their arguments, their philosophy, their priorities, that are defining the agenda on which new Labour thinks and speaks”.

His friend, Martin Jacques, points out: "Tragically, Stuart's ill health slowly but remorselessly curtailed and undermined his ferocious energy. For the last 20 years or so, he was a semi-invalid. But his mind remained as alert and involved as ever. The response to his death has served to demonstrate how much his work has influenced so many people in so many different ways: cultural studies, race and ethnicity, politics, the arts, the media, academe. Little has been left untouched by his intellectual power and insight. Stuart's extraordinary impact was not because he happened to be black and from Jamaica. It was because he was black and from Jamaica. It took an outsider, a black Jamaican, to help us understand and make sense of Britain's continuing decline. He was in so many ways well ahead of his time. It is difficult to think of anyone else that has offered such a powerful insight into what has been happening to us over the past 70 years."