On this day on 3rd March

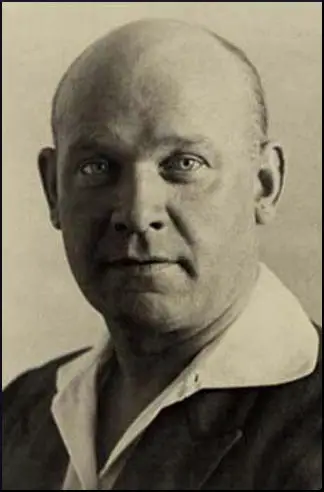

On this day in 1752 parliamentary reformer Thomas Hardy was born in Larbert in Scotland on 3rd March 1752. Hardy's father had been a sailor who died at sea on 1760. After a brief education at the local school, Hardy went to work for his grandfather who taught him the trade of shoemaking.

At the age of twenty-two, Hardy moved to London where he found work as a shoemaker. In 1781 he married the daughter of a carpenter. The couple had six children but they all died young. After working for several different employers, in 1791 Hardy decided to open his own shop in the Piccadilly Road. Soon after starting his business, Hardy heard about Thomas Paine and eventually read his book The Rights of Man.

Trade was difficult and Hardy gradually came to the conclusion that his economic problems were being caused by a corrupt Parliament. Hardy was especially angry about the costs of the war with France. Thomas Hardy later wrote that he now knew that the men in the House of Commons were "falsely calling themselves the representatives of the people, but who were, in fact, selected by a comparatively few individuals, who preferred their own particular aggrandisement to the general interest of the community."

Thomas Hardy and three friends began meeting to discuss whether or not working men should have the vote. After much discussion they decided that they should have that right and on the 25th January 1792 they held a public meeting on parliamentary reform. Only eight people attended but the men decided to form a parliamentary reform group called the London Corresponding Society.

As well as campaigning for the vote, the strategy was to create links with other reforming groups in Britain. Hardy was appointed as treasurer and secretary of the organisation. The society passed a series of resolutions and after being printed on handbills, they were distributed to the public. These resolutions also included statements attacking the government's foreign policy. A petition was started and by May 1793, 6,000 members of the public had signed saying their supported the resolutions of the London Corresponding Society.

In July, 1793, Hardy made a speech where he argued: "We conceive it necessary to direct the public eye, to the cause of our misfortunes, and to awaken the sleeping reason for our countrymen, to the pursuit of the only remedy which can ever prove effectual, namely; a thorough reform of Parliament, by the adoption of an equal representation obtained by annual elections and universal suffrage. To obtain a complete representation is our only aim - condemning all party distinctions, we seek no advantage with every individual of the community will not enjoy equally with ourselves."

At the end of 1793 Thomas Muir began plans to hold a a convention in Edinburgh for supporters of parliamentary reform. The London Corresponding Society sent two delegates but the men and other leaders of the convention were arrested, tried for sedition, and sentenced to fourteen years transportation. The reformers were determined not to be beaten and Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall began to organise another convention.

When the authorities heard what was happening, Hardy and the other two men were arrested and committed to the Tower of London and charged with high treason. The government recruited cartoonists such as James Gillray to mount a propaganda campaign against the leaders of the London Corresponding Society. The main objective of this campaign was to link the reformers with with the actions of the revolutionaries in France.

As a result, of this campaign, a mob attacked Thomas Hardy's house. Mrs. Hardy, pregnant with her sixth child, was forced to escape out of a back window. Hardy later explained: "A mob of ruffians assembled before my house and assailed the windows with stones and brick-bats. They then attempted to break down the shop door, and swore, with the most horrid oaths, that they would either burn or pull down the house. Weak and enfeebled from her situation, Mrs Hardy shouted to her neighbours, who advised her to escape through a small back window. This she attempted, but being very large around the waist, she stuck fast, and it was only by main force that she could be dragged through, much injured by the bruises she had received." Soon after this incident, Mrs. Hardy died in childbirth and the child was still-born.

Thomas Hardy's trial began at the Old Bailey on 28th October, 1794. The prosecution, led by Lord Eldon, argued that the leaders of the London Corresponding Society were guilty of treason as they organised meetings where people were encouraged to disobey King and Parliament. Attempts were made to link the activities of However, the prosecution was unable to provide any evidence that Hardy and his co-defendents had attempted to do this and the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty".

The poor case against Hardy, and the death of his wife had created a great deal of public sympathy for the shoemaker and a large crowd was waiting outside the Old Bailey. The jubilant crowd took the horses from his carriage and drew him through the streets to his home where they observed a short period of silence in memory of his wife and dead child.

After his trial Hardy ceased to be active in politics. He ran a small shoeshop in Covent Garden until his retirement in 1815. Thomas Hardy died in Pimlico on 11th October 1832.

On this day in 1756 William Godwin was born at Wisbech. After three years at day school and three years with a private tutor in Norwich, Godwin entered Hoxton Presbyterian College. Godwin left college as a Tory but after five years as a minister he had developed radical political views. While he was a minister in Beaconsfield William Godwin became friendly with the Rational Dissenters, Richard Price and Joseph Priestley.

In 1787 Godwin left the ministry and became a full-time writer. Inspired by the writings of Tom Paine, Godwin published Enquiry into Political Justice in 1793. In the book Godwin argued that as long as people acted rationally, they could live without laws or institutions. The following year Godwin's pioneering novel, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, was published.

In 1797 Godwin married Mary Wollstonecraft but she died soon after their daughter was born. The following year he wrote Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Women (1798). He also spent several years on the Life of Chaucer (1804).

Godwin's political ideas had a great influence on writers such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. Godwin and Shelley became close friends. However, their relationship was damaged when in 1814, Shelley fell in love and eloped with Mary, Godwin's sixteen-year-old daughter. In later life Godwin concentrated on writing novels, the most popular being Mandeville (1817), Cloudesley (1830) and Deloraine (1833). William Godwin died in 1836.

On this day in 1865 the Freeman's Bureau was established by Congress. The bureau was designed to protect the interests of former slaves. This included helping them to find new employment and to improve educational and health facilities. In the year that followed the bureau spent $17,000,000 establishing 4,000 schools, 100 hospitals and providing homes and food for former slaves.

General Oliver Howard commented: "The government did not establish the Freedmen's Bureau in order to put Army officers in fat places. It does not wish to multiply positions. The object of the Bureau is to aid these people in their transition from the darkness of slavery to the light, to the privileges and the enjoyments of freedom. I have proposed all the time to myself to be always looking forward to the end of the Freedmen's Bureau; and just as soon as any State will show by the action of its officers, by the action of its people, by the sentiments put forth, that they are ready and willing to keep the promise and pledge of our beloved President, endorsed by our Congress, to our freedmen, then they may have the privilege of doing it, and it will relieve me from the responsibility."

The Freeman's Bureau also helped to establish Howard University in Washington in 1867. Instigated by the Radical Republicans in Congress it was named after General Oliver Howard, a Civil War hero and commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees and a leading figure in the Freeman's Bureau. President Andrew Johnson caused great controversy when he said: "Everyone would, and must admit, that the white race was superior to the black, and that while we ought to do our best to bring them up to our present level, that, in doing so, we should, at the same time raise our own intellectual status so that the relative position of the two races would be the same."

Attempts by Congress to extend the powers of the Freemen's Bureau was vetoed by President Johnson in February, 1866. Johnson said: "The bill proposes to establish, by authority of Congress, military jurisdiction over all parts of the United States containing refugees and freedmen. It would by its very nature apply with most force to those parts of the United States in which the freedmen most abound, and it expressly extends the existing temporary jurisdiction of the Freedmen's Bureau, with greatly enlarged powers, over those states in which the ordinary course of judicial proceedings has been interrupted by the rebellion."

This decision increased the conflict between Johnson and the Radical Republicans in Congress. However, white racists in the Deep South were completely opposed to the Freemen's Bureau and the first branch of the Ku Klux Klan was established in Pulaski, Tennessee, in May, 1866. A year later a general organization of local Klans was established in Nashville in April, 1867. Most of the leaders were former members of the Confederate Army and the first Grand Wizard was Nathan Forrest, an outstanding general during the American Civil War. During the next two years Klansmen wearing masks, white cardboard hats and draped in white sheets, tortured and killed black Americans and sympathetic whites. Immigrants, who they blamed for the election of Radical Republicans, were also targets of their hatred. Between 1868 and 1870 the Ku Klux Klan played an important role in restoring white rule in North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia.

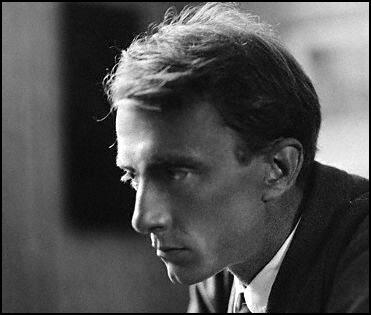

On this day in 1878 Edward Thomas, the son of a civil servant from Wales, was born in London. After his education at St. Paul's School and Lincoln College, Oxford, Thomas became a writer of reviews and topographical works. His first book, The Woodland Life, was published in 1897.

In 1909 Thomas published a biography of Richard Jefferies, the writer and naturalist. Other books by Thomas included The Heart of England (1906), The South Country (1909), The Icknield Way (1913) and the novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913).

In the summer of 1915 Thomas enlisted as a private in the Artists' Rifles. The following year he was made a junior officer and transferred to the Royal Artillery. Lieutenant Edward Thomas began writing war poetry in 1915 but only a couple of these were published before he was killed by an exploding shell at Arras on 9th April, 1917.

After the war, his wife, Helen Thomas wrote about their relationship in As it Was (1926) and World Without End (1931). Their daughter, Myfanwy Thomas, also published her autobiography, One of These Fine Days (1982).

On this day in 1887 the birth of Charlotte Marsh, the daughter of the artist Arthur Hardwick Marsh (1842-1909). She was educated at St Margaret's School, Newcastle upon Tyne, and Roseneath, Wrexham, and then spent a year studying in Bordeaux.

According to her biographer, Michelle Myall, Charlotte was "one of the first women to train as a sanitary inspector but, appalled by the insight her work gave her into the lives of many women, gave up a promising career to join the women's suffrage movement in 1908, to give women a voice in public affairs."

Charlotte Marsh joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) in March 1907 but did not become an active member until she finished her training as a sanitary inspector a year later. As a result of her striking looks she became a WSPU poster girl.

Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "She greatly dislikes her first name Charlotte and all her friends call her Charlie... We liked very much what we saw of her. She is very fair with light hair and a pretty face. She is very tall... She has a wonderful constitution and seems very well after all she has gone through. She has begun the late custom of not taking meat or chicken. She seems a very nice quiet girl."

Charlotte Marsh moved to London and taught by Mary Phillips the art of pavement chalking and it was remarked on how "gamely she stood the jeering and the rough handling we got down Lambeth Way". In May 1908, a wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. Marsh applied for the job of driving the car. However, Vera Holme, got the post, but there were occasions when she worked as Pankhurst's chauffeur.

On 30th June 1908 Charlotte Marsh was one of several suffragettes who jumped up on the railings of the House of Commons. The police pulled them down but when Marsh and Elsie Howey climbed up again they were arrested and charged with obstructing the police. The next day she was found guilty and sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway Prison.

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh, Mary Leigh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper, Patricia Woodcock and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. "The police attempted to move the two women by, among other methods, turning a hosepipe on them and throwing stones. However, Charlotte Marsh and Mary Leigh proved to be formidable opponents and were only brought down from the roof when three policeman dragged them down."

Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work."

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest."

Leigh got four months's imprisonment, Charlotte Marsh three months, the others from a month to fourteen days. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

C.P. Scott wrote to Asquith complaining of the "substantial injustice of punishing a girl like Miss Marsh with two months hard labour plus forcible feeding." According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000): "The Prison Visiting Committee reported that at first she had to be fed by placing food in the mouth and holding the nostrils, but that she later took food from a feeding cup."

Votes for Women, on her release, reported that she had been fed by tube 139 times. Although her father was seriously ill, the authorities refused to release Marsh early. Even though the authorities knew her father was dying, they refused to release her. Marsh left Winson Green Prison on 9th December, 1909. She immediately dashed to her family home in Newcastle upon Tyne but he was already unconscious and he died a few days later.

The hunger-strike and force-feeding had a serious impact on her health. She had lost twenty-one pounds and her throat and chest were very painful and she had a burning sensation in her head. Her doctor described her as being "emaciated, as though recovering from a serious illness and that condition may be extremely prejudicial to her health at some future time."

In February 1910 Charlotte Marsh was WSPU organiser in Oxford. She then moved onto Portsmouth and in September 1910 she ran a WSPU holiday campaign in Southsea. During this period a fellow suffragette described her as "a tall young woman, of quiet, resolute bearing." The Times reported that she was "strikingly beautiful with blue eyes and long corn-coloured hair." Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence described her as one of the "saints of the Church Militant".

On 23rd July, 1910, 10,000 women set out in two processions. The one starting at Westminster was led by the colour-bearer Charlotte Marsh followed by Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence on foot, while the procession from Holland Park in the west was led by Flora Drummond, Eveline Haverfield and Vera Holme, all on horseback. Both processions converged on Hyde Park. On the route over 300 women sold Votes for Women. At the park speeches were given by 150 women including Mabel Tuke, Sylvia Pankhurst, Mary Clarke, Annie Kenney, Ada Flatman, Rachel Barrett, Jane Brailsford, Mary Leigh, Constance Lytton and Emily Wilding Davison.

Marsh visited Eagle House near Batheaston in April 1911 with Annie Kenney and Laura Ainsworth. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Picea Polita, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

In March 1912 Charlotte Marsh took part in a window-smashing campaign in London. It is claimed that she alone smashed nine windows in the Strand during this demonstration. Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "Linley had a nice letter from C. A. L. Marsh in Holloway awaiting her trial as they all refused bail. His birthday letter to her begging her not to take part in violence followed her there. Like the rest, they all think it their duty to take a large share of suffering."

As she had previous convictions Charlotte Marsh was sentenced to six months' in Aylesbury Prison (Holloway was being redecorated). She took part in the hunger-strike and was forcibly fed. She was eleased four and a half months into her sentence.

On her release she and Ada Wright, who was also in very bad health as a result of the hunger-strike ("her throat swelled up so much she could not breathe and her heart became affected") were both sent to Switzerland to recuperate.

On her return she was WSPU organiser in Nottingham. She also spent time in London working alongside Grace Roe. On 14th June 1913 she carried a large wooden cross, she led the funeral procession of her comrade Emily Wilding Davison, who had died as a result of the injuries she sustained when she fell under the hooves of the king's horse at the Epsom Derby on 4th June.

On 24th June, 1914, King George V visited Nottingham. Charlotte Marsh organised protest meetings in order to draw attention to members of the Women Social & Political Union being force-fed in prison. On that day Eileen Casey was arrested at Nottingham and had been found with explosives, detonators, fuses and a substantial amount of flammable material as well as guidebooks to local churches.

The 900-year-old Breadsall All Saints' Church had been destroyed on 4th June. Among the treasures lost in the blaze were a 14th-century door, 16th-century ornate carved wooden benches and an Elizabethan altar. The Rev J. A. Whitaker told a Derby Daily Telegraph reporter: "It has been done by suffragettes, I know it has."

In Nottingham Police Court Eileen Casey was charged with "loitering with intent to commit a felony". In court she claimed: "This will go on till women get the vote... The next time you will find something more important.... I hope I shall be more dangerous before I finish." Charlotte Marsh and other members of the Nottingham WSPU cheered and yelled and were carried out of court kicking and screaming.

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

Charlotte Marsh initially accepted this policy and worked as a motor mechanic before becoming the chauffeur of David Lloyd George "accepting his suggestion that the relationship would promote the victory of the cause of women's enfranchisement". She also worked as a member of the Women's Land Army in Surrey.

Marsh became increasingly critical of the way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU during the First World War. She was especially upset when the WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral."

Anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans". Another article on the Union of Democratic Control carried the headline: "Norman Angell: Is He Working for Germany?" Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield were described as "Bolshevik women trade union leaders" and Arthur Henderson, who was in favour of a negotiated peace with Germany, was accused of being in the pay of the Central Powers. Her daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, who was now a member of the Labour Party, accused her mother of abandoning the pacifist views of Richard Pankhurst.

Charlotte Marsh became so disillusioned by what she believed was a betrayal of the original ideals of the movement founded the Independent Women's Social and Political Union in March 1916. Marsh became its honorary secretary and the group issued a newspaper, Independent Suffragette. The group proclaimed that it would devote itself to the suffrage campaign and would "work in the spirit of the old WSPU".

After the war Marsh worked for Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She then spent some time with the Department of Social Work in San Francisco and then with the Overseas Settlement League. By 1934 she was working with the Public Assistance Department of the London County Council." Marsh was also, along with Margaret Haig Thomas and Theresa Garnett, an executive member of the Six Point Group. She was also vice-president of the Suffragette Fellowship.

Charlotte Marsh was a member of the Labour Party. Her local MP, Edith Summerskill, who became a minister in the Labour government (1945-51), became her friend and she later commented: "I marvelled that this handsome, fragile woman could have possessed sufficient physical courage to face her tormentors and that she had such reserves of moral courage to declare her beliefs over the years under circumstances which often called for a solitary effort, unsupported by the warmth and comfort of her comrades."

Charlotte Marsh, who never married, died at her home, 31 Copse Hill, Wimbledon, on 21st April 1961.

On this day in 1918 Russia signs the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. After the Russian Revolution Lenin demobilized the Russian Army and announced that he planned to seek an armistice with Germany. In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty.

Trotsky commented: "The circumstances of history willed that the delegates of the most revolutionary regime ever known to humanity should sit at the same diplomatic table with the representatives of the most reactionary caste among all the ruling classes. How greatly our opponents feared the explosive power of their negotiations with the Bolsheviks was shown by their readiness to break off the negotiations rather than transfter them to a neutral country."

Arthur Ransome reported in The Daily News. "I wonder whether the English people realize how great is the matter now at stake and how near we are to witnessing a separate peace between Russia and Germany, which would be a defeat for German democracy in its own country, besides ensuring the practical enslavement of all Russia. A separate peace will be a victory, not for Germany, but for the military caste in Germany. It may mean much more than the neutrality of Russia. If we make no move it seems possible that the Germans will ask the Russians to help them in enforcing the Russian peace terms on the Allies."

Trotsky later wrote: "It was obvious that going on with the war was impossible. On this point there was not even a shadow of disagreement between Lenin and me. But there was another question. How had the February revolution, and, later on, the October revolution, affected the German army? How soon would any effect show itself? To these questions no answer could as yet be given. We had to try and find it in the course of the negotiations as long as we could. It was necessary to give the European workers time to absorb properly the very fact of the Soviet revolution." He hoped that Russia's socialist revolution would spread to Germany. This idea was reinforced when Trotsky heard the rumour on 21st January 1918, that a workers' soviet headed by Karl Liebknecht had been established in Berlin. This story was untrue as Liebknecht was still in a German prison.

Leon Trotsky recalled in his autobiography: "On 21st February, we received new terms from Germany, framed, apparently, with the direct object of making the signing of peace impossible. By the time our delegation returned to Brest-Litovsk, these terms, as is well known, had been made even harsher. All of us, including Lenin, were of the impression that the Germans had come to an agreement with the Allies about crushing the Soviets, and that a peace on the western front was to be built on the bones of the Russian revolution."

Lenin continued to argue for a peace agreement, whereas his opponents, including Leon Trotsky, Nickolai Bukharin, Andrey Bubnov, Alexandra Kollontai, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek and Moisei Uritsky, were in favour of a "revolutionary war" against Germany. This belief had been encouraged by the German demands for the "annexations and dismemberment of Russia". In the ranks of the opposition was Lenin's close friend, Inessa Armand, who had surprisingly gone public with her demands for continuing the war with Germany.

After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers and signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "Russia had lost the Ukraine, Finland, her Polish and Baltic territories. In the Caucasus she had to make territorial concessions to Turkey... Three centuries of Russian Territorial expansion was undone."

Trotsky later admitted that he was totally against signing the agreement as he thought that by continuing the war with the Central Powers it would help encourage socialist revolutions in Germany and Austria: "Had we really wanted to obtain the most favourable peace, we would have agreed to it as early as last November. But no one raised his voice to do it. We were all in favour of agitation, of revolutionizing the working classes of Germany, Austria-Hungary and all of Europe."

Herbert Sulzbach recorded in his diary: "The final peace treaty has been signed with Russia. Our conditions are hard and severe, but our quite exceptional victories entitle us to demand these, since our troops are nearly in Petersburg, and further over on the southern front, Kiev has been occupied, while in the last week we have captured the following men and items of equipment: 6,800 officers, 54,000 men, 2,400 guns, 5,000 machine-guns, 8,000 railway trucks, 8,000 locomotives, 128,000 rifles and 2 million rounds of artillery ammunition. Yes, there is still some justice left, and the state which was first to start mass murder in 1914 has now, with all its missions, been finally overthrown."

Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belorus, and Ukraine now became independent countries. The treaty deprived "Russia of a territory nearly as large as Austria-Hungary and Turkey combined, with 56,000,000 inhabitants, or 32 per cent of her whole population; a third of her railway mileage, 73 per cent of her total iron ore, 89 per cent of her total coal production; and more than 5,000 factories and industrial plants. Moreover, Russia was obliged to pay Germany an indemnity of six billion marks." The historian, John Wheeler-Bennett commented that the treaty was a "humiliation without precedent or equal in modern history."

On this day in 1933 Ernst Thaelmann, leader of the German Communist Party (KPD) was arrested by the Gestapo. He was later able to smuggle out details of his interrogation. "It is nearly impossible to relate what happened for four and a half hours, from 5.00pm to 9.30pm in that interrogation room. Every conceivable cruel method of blackmail was used against me to obtain by force and at all costs confessions and statements both about comrades who had been arrested, and about political activities. It began initially with that friendly 'good guy' approach as I had known some of these fellows when they were still members of Severing's Political Police (during the Weimar Republic). Thus, they reasoned with me, etc., in order to learn, during that playfully conducted talk, something about this or that comrade and other matters that interested them. But the approach proved unsuccessful. Was then brutally assaulted and in the process had four teeth knocked out of my jaw. This proved unsuccessful too. By way of a third act they tried hypnosis which was likewise totally ineffective. But the actual high point of this drama was the final act. They ordered me to take off my pants and then two men grabbed me by the back of the neck and placed me across a footstool. A uniformed Gestapo officer with a whip of hippopotamus hide in his hand then beat my buttocks with measured strokes, Driven wild with pain I repeatedly screamed at the top of my voice. Then they held my mouth shut for a while and hit me in the face, and with a whip across chest and back. I then collapsed, rolled on the floor, always keeping face down and no longer replied to any of their questions. I received a few kicks yet here and there, covered my face, but was already so exhausted and my heart so strained, it nearly took my breath away."

Wilhelm Pieck had managed to escape to the Soviet Union. In July 1936 he issued a statement calling for the release of Thälmann: "If we succeeded in raising a tremendous storm of protest throughout the world, it will be possible to break down the prison walls and as in the case of Dimitrov, deliver Thaelmann from the clutches of the Fascist hangmen. The fact that Ernst Thaelmann has got to spend his fiftieth birthday in the gaols of Hitler-Fascism is an urgent reminder to all the anti-Fascists of the whole world that they must intensify to the utmost their campaign for the release of Thaelmann and the many thousands of imprisoned victims of the White Terror."

Ernst Thälmann spent over eleven years in solitary confinement. He was executed in Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 18th August 1944. A few days later the Nazi government announced that Thälmann and Rudolf Breitscheid had been killed in an Allied bombing attack.