On this day on 23rd April

On this day in 1702 Margaret Fell, aged eighty-eight, died at Swarthmoor Hall. Margaret Askew was born at Marsh Grange, near Dalton in Furness, Lancashire, in 1614. She was the eldest of two daughters of John Askew, landowner, of Marsh Grange. Her father was a man of "considerable estate which had been in his name and family for several generations". Askew insisted that Margaret and her sister were taught to read and write. Her social standing and education made her an excellent prospect for marriage.

In 1632, at the age of seventeen, Margaret married the thirty-three year old Thomas Fell. He was a barrister,who owned Swarthmoor Hall. In 1641, Thomas became a Justice of the Peace for Lancashire, and in 1645 a member of the House of Commons for Lancaster and a close ally of Oliver Cromwell, although he later became critical of the way he ruled the country.

In 1649 Thomas Fell became vice-chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and an attorney at Gray's Inn, and a judge of assize for the Chester and North Wales circuit. With her husband rarely at home Margaret "as a literate woman - a rare phenomenon in the period" she oversaw the family estates and businesses, that included the mining of iron ore.

It has been claimed that the "isolation of the north and the dearth of places for lodging brought out Margaret's hospitality. She received the rich and poor alike; her open table brought a variety of interesting, notable, and oftentimes garrulous conversationalists. Everyone in Lancashire knew of this and passed on what they knew of it to strangers."

In late June 1652, George Fox interrupted a service at a church in Ulverston. His words had an impact on Margaret Fell, who was in the congregation. She gave him refuge and by the time he left Swarthmoor Hall he had converted Margaret and her daughters, and most of her household to Quakerism. Margaret's husband was in London at the time. Margaret was unsure of what her absent husband's reaction would be to these happenings, was, as she put it, "stricken with such sadness that I knew not what to do."

As Bonnelyn Young Kunze has pointed out: "Upon his return Judge Fell was troubled by his wife's sudden conversion to this new dissenting sect, but Margaret convinced her husband of her new-found faith and introduced Fox to him. After her conversion to Quakerism she ceased to attend St Mary's, Ulverston, although her husband continued to attend regularly without her, and never converted to the sect. However, his sympathy towards Quakers was important, especially given his judicial position, and he allowed the Friends to hold their meetings at Swarthmoor Hall free from persecution."

Margaret Fell was one of the most important converts to Quakerism. Her name and connections, practical organizational abilities and energies, as well as her husband's influence, were all assets Fell brought to the effort. She wrote to her husband "the truth will stand when all other things shall be as stubble". Margaret was described by informers that she was the "chief maintainer" of the sect in the region.

At first Quaker meetings were in people's homes, barns or by the roadside. The Quakers built "Meeting Houses" only when their own homes became too small. Given the idea of spiritual equality, anyone could speak when prompted by God. Prayer involved the speaker kneeling and everyone else standing and removing their hats, the only time Quakers did so. "Quakers also performed signs, such as 'going naked', as part of their public witness to the new covenant they had established with God and the apostasy of the old ways of believing."

In 1653 Fox was arrested in Carlisle after he said he considered himself God's son, that he had seen God's face, and that God was the original word and that the Scriptures were mere human writings. He was accused of blasphemy and heresy and remanded in the city dungeon. He was beaten with a cudgel by his jailer after he refused to buy the food his keepers sold. He was released after Margaret Fell wrote a letter for general circulation attacking those in government who professed to favour reformation and liberty of conscience while imprisoning people like Fox.

Fox always insisted that God called women to be preachers and evangelists just as he had traditionally called men. It has been estimated that ministry of women, made up 45% of the early Quaker movement. Margaret Fell and Elizabeth Hooton, became two of the Quakers most respected leaders. These women also raised important questions about overturning other traditional relationship between the sexes. Men began to argue that women preachers would lead to immorality. One critic complained that even conversing with women seduced and drew them away from their husbands. One observer claimed that the Quakers "hold a community of women and other men's wives and practice living upon one another too much."

As Jacqueline Broad pointed out: "Margaret Fell is not an advocate of an egalitarian concept of reason or a supporter of equal educational opportunities for women. Her arguments in favour of female preaching rest on a principle of spiritual equality, or the idea that both men and women have the supernatural light of Christ within them. But for Fell, the ability to hearken to that light implicitly requires that women possess a natural capacity to discern the truth for themselves, to exercise strength of will, and to exhibit moral virtue or excellence of character. In these respects, Fell's arguments for female preaching contain an implicit feminist challenge to negative perceptions about women's moral and intellectual abilities in her time."

It was important for Margaret Fell to explain to Charles II that despite her anti-authoritarian beliefs she was not an advocate of active resistance to political authority. In a letter to the king she was one of the first writers to articulate the Quaker philosophy of peace and non-resistance she declared that the Quakers aspire "to live peaceably with all men, And not to Act any thing against the King nor the peace of the Nation, by any plots, contrivances, insurrections, or carnal weapons to hurt or destroy either him or the Nation thereby, but to be obedient unto all just & lawful Commands".

In Fell's 1660 publication, A Declaration and an Information from Us, the People Called Quakers, we have the first official public statement affirming pacifism as a tenet of Quaker belief and practice. She delivered her peace testimony on horseback to King Charles II on the event of her new husband George Fox's arrest while worshipping at Swarthmoor Hall: "Wherein have we offended any man any otherwise then in that we worship God in the Spirit...and for this must we be made the object of merciless men's cruelty... We are a people that follow after the things that make for peace, love and unity. It is our desire that others' feet walk in the same. We do deny and bear our testimony against all strife, wars, and contentions that come from the lusts that war in their members, that war against the soul, which we wait for, and watch for in all people. We love and desire the good of all."

On 6 January, 1661, Thomas Venner and a group of fifty members of the Fifth Monarchists, attempted to overthrow the the seven-month-old regime of Charles II, by taking over St. Paul's Cathedral. A combined group of volunteers and regular forces had little difficulty in dealing with the rebels and they were either killed or captured. Venner and thirteen others were hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason. Their heads were stuck up on London Bridge as a warning to others who might attempt similar rebellious acts.

Two days after Venner's execution Fox and eleven other Quakers issued what latter became known as the "Peace Testimony". The signers did not include militants such as Edward Burrough and Thomas Salthouse. The statement said it wanted to remove "the ground of jealously and suspicion" regarding "the harmless and innocent people of God, called Quakers." It then went on to argue: "We utterly deny all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatsoever; and this is our testimony to the whole world. The spirit of Christ, by which we are guided, is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we do certainly know, and so testify to the world, that the spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the kingdom of Christ, nor for the kingdoms of this world."

Despite this statement the Venner's Rising led to repressive legislation to suppress non-conformist sects. This included the Quakers. George Fox and other leaders were taking into custody. Margaret Fell wrote to the king asking for Fox to be released. She warned that "the people of God, called Quakers," had limited patience; they would "love, own, and honor the king, and these our present governors, so far as they do rule for God and his truth and do not impose anything upon people's consciences."

Thomas Fell died in 1658. This deprived the Quakers of a judicial protector. Margaret Fell was left a widow, aged forty-four, with eight unmarried children. She later wrote of her husband that he had been "a tender loving husband to me, and a tender father to his children", and had "left a good and competent estate for them". Margaret was left Swarthmoor Hall and 50 adjacent acres (she had already inherited the Askew estate at Marsh Grange from her father). Fell's death allowed Margaret to become an active Quaker minister who wrote and travelled and who became a political spokeswoman of the movement. She emerged as in effect a co-leader of early Quakerism with Fox.

Fox often described Margaret as the "nursing mother" of the movement. Her status and experience gave her self-assurance in her dealings with powerful men. This included communicating with Charles II over the persecution of Quakers. It was claimed that within the Society of Friends she "doled out assignments like a Quaker bishop". She was also extremely loyal to Fox and gave him her full support in his conflicts with James Nayler, John Perrot and Isaac Penington. Despite her own strong opinions she always deferred to Fox about issues within the movement.

In May 1669 Fox aged 35 and Margaret aged 45 agreed to marry. In mid-October 1669 the couple duly informed the Bristol meeting of their intentions, first to the men's meeting and then to a joint meeting of men and women. They married on 27 October with Margaret's daughters and their husbands present. Margaret's only son, George Fell, who disapproved of the match, did not attend. Fox signed a contract waiving his rights to Margaret's property, and her daughters, who were to inherit Swarthmoor Hall should she remarry, agreed to allow her to live there. A few days after the wedding Fox continued on his missionary visits while Margaret returned to Swarthmoor.

It has been argued that there "were no passionate feelings on either side" and that Fox expressed "all the excitement of someone completing a business deal". (25) In an explanatory letter addressed to all Quakers Fox said he had been "commanded" to take Margaret as his wife and added that the marriage testified to "the church coming out of the wilderness, and the marriage of the Lamb before the foundation of the world". Fox wanted it to be understood that his was an "honorable marriage and in an undefiled bed" in an effort to undermine the rumours of sexual misconduct between the two by anti-Quaker authors such as John Harwood.

Although she was 55 years old Margaret told friends that she hoped to give birth to another child. The couple spent ten days together before Fox continued his missionary work. In April 1670, Margaret was arrested and detained at Lancaster jail. She claimed that she was pregnant and this news was welcomed by other Quakers. However, no baby was born and it has been suggested that Margaret had convinced herself that she was carrying a child, a condition known as pseudocyesis (imaginary or false pregnancy).

In September 1662 Charles II had announced the Declaration of Indulgence that suspending laws against dissenters. This resulted in the release of 491 Quakers from prison. An angry House of Commons forced the king to withdraw the declaration and implement, in its place, the Test Act (1673). Although aimed at Catholics, Fox saw that this law could be applied to them because of their testimony against oaths and protested vigorously against it. William Penn was the main figure in Parliament who argued against this legislation.

On 17th December, 1673, Fox was arrested and sent to Worcester Jail. He was twice freed briefly on writs of habeas corpus and allowed to go to London. However, he was unwilling to accept a pardon and returned to prison. Fox fell ill, and for a time became so weak he could hardly utter a word and needed fresh air in his closed dungeon. He spent fourteen months in prison until his final release in February 1675.

Fox now concentrated on sorting out the conflict that emerged between men and women in Bristol. Isabel Yeamans, the daughter of Margaret Fell, had upset men in the city by setting up a monthly meetings for women. This was in response to her mother's call for women's rights in Quaker meetings in Women's Speaking Justified (1666) where she argued: "Let this Word of the Lord, which was from the beginning, stop the Mouths of all that oppose Women's Speaking in the Power of the Lord; for he hath put Enmity between the Woman and the Serpent; and if the Seed of the Woman speak not, the Seed of the Serpent speaks; for God hath put Enmity between the two Seeds; and it is manifest, that those that speak against the Woman and her Seed's Speaking, speak out of the Envy of the old Serpent's Seed."

William Rogers, a leading Quaker in the city, demanded to know why the women had proceeded on their own. A committee of six, including some of the most powerful Quakers in Bristol, was instructed to attend the next women's meeting to discuss the matter. The women eventually agreed to defer "to the wisdom of God in the Friends of the men's meeting". At a meeting of thirty male Quakers it was agreed that in future women had a "duty to mind only those things that tend to peace." The Bristol women acquiesced to this demand.

Fox, who had been in America at the time of this dispute, published details of new rights for women in the movement. He instructed that couples seeking to be married must have their proposed union examined twice by both men's and women's meetings. This was confirmed in a letter to his wife in May 1674. In an epistle the following year Fox defended women's meetings in general terms, rebuking those who called them into question, but it neglected to address what many male Quakers considered the demeaning requirement that men seek approval for marriage from women.

At a meeting in May 1675, Quaker leaders in London, including William Penn, Thomas Salthouse. Alexander Parker and George Whitehead, published a document concerning the role of women in the movement. It stated that all marriages be cleared twice by women's and men's meetings, to make sure that "all foolish and unbridled affections" be speedily brought under God's judgment. It also reminded Quakers that women's meetings, just like men's meetings, had been set up with God's counsel and sharply admonished those who sneered at them as "synods" and "Popish impositions". Violators of these instructions - "disorderly walkers" - should have their names recorded.

It has been claimed by one Quaker historian "Separate men's and women's Business Meetings were recommended at all levels of the structure, each with their own areas of responsibility. Fox argued this was necessary for women to have their own voice, although their areas of influence were highly gendered and limited to pastoral duties such as marriage arrangements and poor relief. It seems that whilst the ideal of spiritual equality persisted, political equality did not."

In his final years Fox lived in London. Margaret continued to live in Swarthmoor Hall. However, in April, 1690, aged seventy-six, did visit her husband. On 11 January 1691, Fox attended the Gracechurch Street meeting and, as usual, preached. At the end of the meeting he complained of a "coldness near his heart" and went to bed at the nearby house of Henry Gouldney, a local Quaker with whom Fox had stayed several times before. He died of congestive heart failure two days later.

After the death of her husband Margaret remained at Swarthmoor, apart from one trip to London in 1697. In June 1698 she wrote a letter to William III to commend him on his "Gentle Government and Clemency, and Gracious Acts". In an epistle to Quakers, written in April 1700, she criticized the emerging interest in Quaker conformity of dress. She called the grey costume that was becoming popular a 'silly poor gospel'. The new style of dress was setting Quakers apart from the world as God's special people, and it was not an indicator of their interior spiritual religion and purity.

On this day in 1794 William Godwin writes a letter of support to Joseph Gerrald, a member of the Society of the Friends of the People, who had been arrested and charged with sedition. "Your trial, if you so please, may be a day such as England, and I believe the world, never saw. It may be the means of converting thousands, and, progressively, millions, to the cause of reason and public justice. You have a great stake, you place your fortune, your youth, your liberty, and your liberty, and your talents on a single throw. If you must suffer, do not I conjure you, suffer without making use of this opportunity of telling a tale upon which the happiness of nations depends. Spare none of the resources of your powerful mind. What an event would it be for England and mankind if you would gain an acquittal!"

On this day on 1796 Thomas Fyshe Palmer writes about the death Joseph Gerrald. "Gerrald was at my house the last two months and lay in my rooms. I attended him night and day, and the attention of my friends who live with me was equal to mine. Some few hours before his death, he called me to his bedside, 'I die', said he, 'in the best of causes and, as you witness, without repining'."

Palmer, Gerrald, Thomas Muir, William Skirving and Maurice Margarot were members of the Society of the Friends of the People, who had been arrested and charged with sedition. The trial of began on 10th March 1794. Gerrard defiantly wore his hair loose and unpowdered in the French style. He made no real attempt to defend himself against the charges and instead concentrated on using the court to express his views on parliamentary reform. Gerrald upset the judge, Lord Braxfield, when he argued that Jesus Christ was a radical reformer. Gerrald ended his speech with the words: "What ever may become of me, my principles will last for ever. Whether I shall be permitted to glide gently down the current of life, in the bosom of my native country, among those kindred spirits whose approbation constitutes the greatest comfort of my living; whether I be doomed to drag out the remainder of my existence amidst thieves and murders, my mind, equal to either fortune, is prepared to meet the destiny that awaits it." Lord Braxfield's response was to sentence Gerrald to fourteen years transportation.

In February 1793, they were all found guilty of writing and publishing pamphlets on parliamentary reform and placed on prison Hulks on the Thames in preparation for their journey to Australia. Radicals in the House of Commons immediately began a campaign to save the men now being described as the Scottish Martyrs. On 24th February, 1793, Richard Sheridan presented a petition to Parliament that described the men's treatment as "illegal, unjust, oppressive and unconstitutional". Charles Fox pointed out in the debate that followed that Palmer had done "no more than what had done by William Pitt and the Duke of Richmond" when they had campaigned for parliamentary reform.

While waiting to be transported to Australia, a government minister, Henry Dundas, offered to arrange for Gerrald to be given his freedom if he promised to stop advocating parliamentary reform. Gerrald refused and on 25th May he left Portsmouth aboard the Sovereign. Gerrald was seriously ill when he arrived in Australia on 5th November, 1795. John Fyshe Palmer looked after him for several months. Gerrald died of tuberculosis on 16th March, 1796.

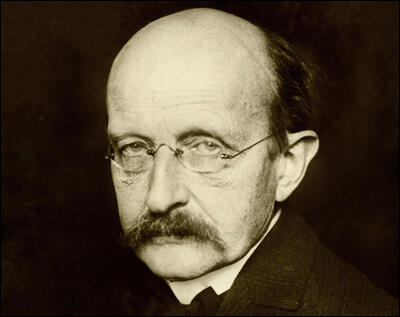

On this day in 1858 scientist Max Planck, the son of a professor of law, was born in Kiel, Germany, on 23rd April, 1858. He studied physics at the University of Munich (1874-1877) and the University of Berlin (1877-78) before receiving his doctorate in 1879.

He taught at the University of Munich before being appointed associate professor at the University of Kiel. Planck researched into the manner in which heated bodies radiate energy led him to argue that energy is emitted only in indivisible amounts, called "quanta", the magnitudes of which are proportional to the frequency of the radiation.

Planck's theories were in conflict with classical physics and his work is said to have marked the commencement of modern science. Albert Einstein used Planck's quantum theory to explain photoelectricity and Niels Bohr successfully applied the quantum theory to the atom. In 1918 Planck was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics.

In 1930 he was appointed as president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in 1930. An opponent of Adolf Hitler, Planck resigned his position in 1937 in protest against the decision by Bernard Rust, the minister of education, to sack Jewish teachers from Germany's universities.

Planck refused to work on any of Germany's war research projects. In 1944 Planck's youngest son, Erwin Planck was arrested and charged with involvement in the July Plot against Adolf Hitler. He was killed while being tortured by the Gestapo in 1945.

Max Planck died on 4th October, 1947.

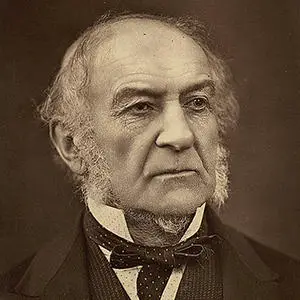

On this day in 1880, finally and with great reluctance, Queen Victoria appoints William Gladstone as prime minister. In the 1880 General Election Gladstone contested the seat of Midlothian. He made eighteen important speeches. "The verbatim reporting of Gladstone's speeches ensured that they were available to every newspaper-reading household the next morning". Gladstone defeated his conservative opponent, William Montagu Douglas Scott, on 5th April 1880 by 1,579 votes to 1,368.

It was a great victory for the Liberal Party who won 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. Benjamin Disraeli resigned and Queen Victoria invited Spencer Cavendish, Lord Hartington, the official leader of the party, to become her new prime minister. He replied that the Liberal majority appeared to the nation as being a "Gladstone-created one" and that Gladstone had already told other senior figures in the party he was unwilling to serve under anybody else.

Victoria explained to Hartington that "there was one great difficulty, which was that I could not give Mr. Gladstone my confidence." She told her private secretary, Sir Henry Frederick Ponsonby: "She will sooner abdicate than send for or have any communication with that half mad firebrand who would soon ruin everything and be a dictator. Others but herself may submit to his democratic rule but not the Queen."

Victoria now asked to see Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville. He also refused to be prime minister, explaining that Gladstone had a "great amount of popularity at the present moment amongst the people". He also suggested that Gladstone, now aged 70, would probably retire by 1881. Victoria now agreed to appoint Gladstone as her prime minister. That night he recorded in his diary that the Queen received him "with the perfect courtesy from which she never deviates".

Queen Victoria attempted to select Gladstone's cabinet ministers. He rejected this idea and appointed those who he felt would remain loyal to him. Gladstone who was described as looking "very ill and haggard, and his voice feeble" surprised the Queen by telling her that he intended to be his own Chancellor of the Exchequer. Joseph Chamberlain, the only member of the left-wing group within the Liberal Party, who was given a senior post in the government.

On this day in 1907 photographer Lee Miller is born in Ploughkeepsie, New York.. Her father was an engineer and an amateur photographer and trained her to use the camera at an early age.

Lee moved to New York in 1927 where she worked as a model. Photographed by Edward Steichen, she appeared on the front cover of Vogue. However, determined to become a photographer, she studied at the Arts Students League (1927-29) and opened her own studio in the city in 1932.

After her marriage to the the art historian, Roland Penrose, Miller moved to London where she worked as a photographer for Vogue. Miller also photographed the impact of the Blitz on the British people and this was published in the book Grim Glory.

In 1942 Miller became an official war correspondent for U.S. forces in Europe. She accompanied Allied troops during the liberation of France and photographed the scenes when the Red Army and the US Army joined up for the first time on the Elbe River. Miller was also with the troops when they liberated Buchenwald and Dachau.

At the end of the war Miller returned to England where she continued to work as a freelance journalist and photographer. Lee Miller died in Chiddingly, Sussex, on 21st July, 1977.

On this day in 1909 Emily Blathwayt writes in her diary about Clara Clodd. "Beautiful day for the tree planting and Linley photographed the three in a group at each tree. Annie put the West one, Mrs. P. Lawrence, South, and Lady Constance the East. Miss Codd came to the field. Then Linley took others indoors and they left in his motor."

In 1907 Clodd was asked by Aeta Lamb to become a steward of meeting being addressed by Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney at a local Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) meeting. The following year she became the honorary secretary of the newly founded Bath branch of the WSPU. Codd became a frequent visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston, the home of fellow WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt. Her father, Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest".

Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay at Eagle House. Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU at Batheaston. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account.

The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time."

Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary about how Clara and Annie Kenney were attacked during a meeting in Bath. "Clara Codd was not allowed to speak but the chairman Annie said everything to the purpose as she always does and the reporters have put it all in. When the platform was about to be rushed they broke up the meeting and got some of the ladies into a smaller room where they spoke... Annie was begged to go out by the back, but she said she would not sneak out like a Cabinet Minister. The police with difficulty protected our poor man from Bence's with the fly and our four got off safely. We read Clara who walked was sadly hustled and the police got her party into the York House Mews."

On 13th October 1908 Clara Codd was arrested at a demonstration outside the House of Commons and sentenced to one month's imprisonment. Christabel Pankhurst suggested that Clara should become a full-time WSPU organiser working under Flora Drummond at a salary of £2 a week. However, she turned down the offer and after this seems to have left the WSPU.

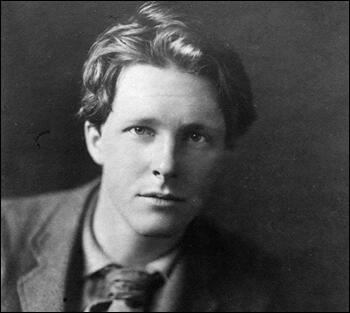

On this day in 1915 poet Rupert Brooke dies. Rupert Chawner Brooke, the second of the three sons born to William Parker Brooke (1850–1910), a housemaster at Rugby School, was born on 3rd August, 1887. According to his biographer, Adrian Caesar: "Brooke attended a preparatory school, Hillbrow, as a day boy, 1897–1901, and then proceeded to take his place at Rugby. Home and school thus became the same place, and psychologically this situation may have represented the worst of both worlds: he experienced the sexually sequestered and confusing world of the public school, while simultaneously coping with the emotional intensities generated by a possessive mother and a distantly affectionate father."

In 1906 he won a scholarship to King's College. While at Cambridge University Brooke joined the Fabian Society. Other members at Cambridge at the time included: Hugh Dalton, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves. During this period Brooke met several leaders of the movement including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb. Like fellow members he developed an enthusiasm for long walks, camping, nude bathing, and vegetarianism.

Brooke wrote at the time about the Fabians: "they're really sincere, energetic, useful people, and they do a lot of good work." He was especially impressed with Wells who he described as being "fantastic". However, he was more critical of other members. He wrote that he wanted the Fabians to take "a more human view... They confound the means with the end; and think that a compulsory living wage is the end, instead of a good beginning."

Beatrice Webb established the National Committee for the Break-Up of the Poor Law. According to the authors of The First Fabians (1977): "Beatrice directed a campaign of meetings, conferences, summer schools, study circles and propaganda leaflets which within a few months had recruited over sixteen thousand members and had set up branches across the country. Its energies came largely from young people. Rupert Brooke, pedalling around the Cambridgeshire villages with his campaign literature, collected the litany of names for his famous poem on Grantchester, and many aspiring politicians on the left served their apprenticeship in the campaign."

Brooke began writing poetry and during the next few years had two collections of verse published, Poems (1911) and Georgian Poetry (1913). Adrian Caesar argues: "Despite this parade of achievement, Brooke's private life proceeded from confusion to chaos and crisis. Paradoxically, his emotional and his psychosexual life were ruled by the puritanism which he dissected in his academic writing. To a revulsion from the body he added a deep uncertainty as to the direction of his desires.... James Strachey also remained a close friend during this period, although Brooke refused at least two invitations to share his bed. Further chaste entanglements developed in 1910 and 1911 with Katherine (Ka) Laird Cox (1887–1938) and Elisabeth van Rysselberghe (1889/90–1980) respectively. Brooke's unresolved relationships with Noel and Ka precipitated a nervous breakdown in early 1912, following which he consummated his relationship with Ka. But this led to more misery, and there is some evidence to suggest that Ka bore his stillborn child later that year."

On the outbreak of the First World War Brooke joined the Royal Naval Division and in October 1914 took part in the Antwerp expedition. After this experience he wrote several poems which made him famous including, Peace, Safety and The Soldier. These poems are now considered as representative of the naïve patriotism of Brooke's generation.

In February 1915 Brooke sailed on the Grantully Castle for the Dardanelles. While on board he developed acute blood poisoning and although transferred to a hospital ship died on 23rd April 1915. Rupert Brooke was buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

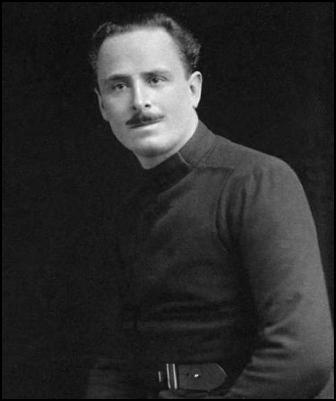

On this day in 1934 the Daily Express comes out in support of Oswald Mosley. The newspaper described him at one of British Union of Fascists rallies: "As a spectacle it was an impressive sight.. The raucous presentrnent of Sir Oswald's voice began to crash round the hall. Musical as it was through the microphone, the voice was weaving its spell-the peroration was perfect. Sir Oswald, his voice rising and falling, talked of the makers of the Empire, of the Constitution and history."

On this day in 1941 Charles A. Lindbergh argues for the defeat of Britain in the Second World War.

I have said before and I will say again that I believe it will be a tragedy to the entire world if the British Empire collapses. That is one of the main reasons why I opposed this war before it was declared and why I have constantly advocated a negotiated peace. I did not feel that England and France had a reasonable chance of winning.

France has now been defeated; and despite the propaganda and confusion of recent months, it is now obvious that England is losing the war. I believe this is realized even by the British government. But they have one last desperate plan remaining. They hope that they may be able to persuade us to send another American Expeditionary Force to Europe and to share with England militarily as well as financially the fiasco of this war.

I do not blame England for this hope, or for asking for our assistance. But we now know that she declared a war under circumstances which led to the defeat of every nation that sided with her, from Poland to Greece. We know that in the desperation of war England promised to all those nations armed assistance that she could not send. We know that she misinformed them, as she has misinformed us, concerning her state of preparation, her military strength, and the progress of the war.

In time of war, truth is always replaced by propaganda. I do not believe we should be too quick to criticize the actions of a belligerent nation. There is always the question whether we, ourselves, would do better under similar circumstances. But we in this country have a right to think of the welfare of America first, just as the people in England thought first of their own country when they encouraged the smaller nations of Europe to fight against hopeless odds. When England asks us to enter this war, she is considering her own future and that of her Empire. In making our reply, I believe we should consider the future of the United States and that of the Western Hemisphere.

It is not only our right but it is our obligation as American citizens to look at this war objectively and to weigh our chances for success if we should enter it. I have attempted to do this, especially from the standpoint of aviation; and I have been forced to the conclusion that we cannot win this war for England, regardless of how much assistance we extend.

I ask you to look at the map of Europe today and see if you can suggest any way in which we could win this war if we entered it. Suppose we had a large army in America, trained and equipped. Where would we send it to fight? The campaigns of the war . show only too clearly how difficult it is to force a landing, or to maintain an army, on a hostile coast.

Suppose we took our Navy from the Pacific and used it to convoy British shipping. That would not win the war for England. It would, at best, permit her to exist under the constant bombing of the German air fleet. Suppose we had an air force that we could send to Europe. Where could it operate? Some of our squadrons might be based in the British Isles, but it is physically impossible to base enough aircraft in the British Isles alone to equal in strength the aircraft that can be based on the continent of Europe.

On this day in 1945 Klaus Bonhoeffer is executed. Klaus Bonhoeffer had been entenced to death on 2nd February, but was held in captivity for over two months. He was shot in Berlin as the Red Army approached the city.

Klaus Bonhoeffer, the son of the psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer, and the older brother of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, was born Breslau, Germany, in 1901. He went to the Grunewald Gymnasium in Berlin where he became friends with Hans Dohnányi. He studied as a lawyer and in 1936 was appointed head of the Lufthansa legal department.

An opponent of Adolf Hitler Bonhoeffer became involved in an attempt to overthrow the government in Nazi Germany. According to Louis L. Snyder: "From the beginning of his career he was convinced that the Nazi movement had stained the honour of his country. He therefore worked with various Resistance groups to eliminate it."

Dietrich Bonhoeffer found work as a pastor in London. When he heard that Martin Niemöller and Karl Barth had formed the anti-Nazi Confessional Church, Bonhoffer decided to return and join the struggle. He wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr: "I must live through this difficult period of our national history with the Christian people of Germany…. Christians in Germany are going to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive, or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying our civilization. I know which of these alternatives I must choose."

Elisabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern have argued: "Seeing that the Nazis intended to impose their dogma - that race, not religion, determined one’s civic identity - on the churches, Bonhoeffer joined other pastors in challenging the conservative-reactionary church leaders who acceded to this view. The dissidents organized themselves into what became known as the Confessing Church, which more than two thousand pastors joined, and Bonhoeffer alerted ecumenical organizations abroad to the Nazi threats. In 1935, he readily accepted a teaching position at a remote Pomeranian estate in a quasi-legitimate “preachers’ seminary.” He spent three years there, but went often to Berlin to see his parents - and to talk to his brother-in-law Hans, who was fighting the Nazis on different fronts." By 1937 over 800 pastors had been arrested. Bonhoeffer was banned from public meetings in Berlin, but he continued to teach and guide his students in Pomerania.

In early 1943 a group of anti-Nazis that included Klaus Bonhoeffer, Wilhelm Canaris, Friedrich Olbricht, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Werner von Haeften, Claus von Stauffenberg, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Peter von Wartenburg, Hans Dohnányi, Erwin Rommel, Franz Halder, Hans Gisevius, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ludwig Beck and Erwin von Witzleben met to discuss what action they should take. Initially the group was divided over the issue of Hitler. Gisevius and a small group of predominantly younger conspirators felt that he should be killed immediately. Canaris, Witzleben, Beck, Rommel and most of the other conspirators believed that Hitler should be arrested and put on trial. By using the legal system to expose the crimes of the regime, they hoped to avoid making a martyr of Hitler. Oster and Dohnanyi argued that after Hitler was arrested he should be brought before a panel of physicians chaired by Dohnanyi's father-in-law, the psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer, and declared mentally ill.

On 5th April 1943, Schutzstaffel (SS) officers entered the Abwehr building in Berlin. Wilhelm Canaris was told that they had received information that Hans Dohnányi had been taking bribes for smuggling Jews into Switzerland. After carrying out a search of the premises Dohnányi was arrested. Later that day Dohnányi's wife, Klaus Bonhoeffer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer were also taken into custody. Dohnányi managed to send out a message to General Ludwig Beck asking him to destroy his records of the conspiracy. However, Beck insisted that they be preserved for historical evidence of what Good Germans had done to fight Nazism.

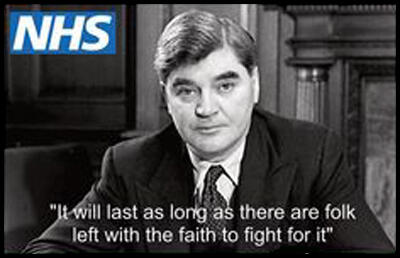

On this day in 1951 Aneurin Bevan resigns from government over cuts to the National Health Service.

I now come to the National Health Service side of the matter. Let me say to my hon. Friends on these benches: you have been saying in the last fortnight or three weeks that I have been quarrelling about a triviality - spectacles and dentures. You may call it a triviality. I remember the triviality that started an avalanche in 1931. I remember it very well, and perhaps my hon. Friends would not mind me recounting it. There was a trade union group meeting upstairs. I was a member of it and went along. My good friend, "Geordie" Buchanan, did not come along with me because he thought it was hopeless, and he proved to be a better prophet than I was. But I had more credulity in those days than I have got now. So I went along, and the first subject was an attack on the seasonal workers. That was the first order. I opposed it bitterly, and when I came out of the room my good old friend George Lansbury attacked me for attacking the order. I said, "George, you do not realise, this is the beginning of the end. Once you start this there is no logical stopping point."

The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million. No, £4,000 million. He has taken £13 million out of the Budget total of £4,000 million. If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct...

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop? I have been accused of 42 having agreed to a charge on prescriptions. That shows the danger of compromise. Because if it is pleaded against me that I agreed to the modification of the Health Service, then what will be pleaded against my right hon. Friends next year, and indeed what answer will they have if the vandals opposite come in? What answer? The Health Service will be like Lavinia - all the limbs cut off and eventually her tongue cut out, too...

Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right hon. and hon. Friends cannot escape. Why, therefore, has it been done in this way?

After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?

Why has the cut been made? He cannot say, with an overall surplus of over £220 million and a conventional surplus of £39 million, that he had to have the £13 million. That is the arithmetic of Bedlam. He cannot say that his arithmetic is so precise that he must have the £13 million, when last year the Treasury were £247 million out. Why? Has the A.M.A. succeeded in doing what the B.M.A. failed to do? What is the cause of it? Why has it been done?

I will tell my hon. Friends something else, too. There was another policy - there was a proposed reduction of 25,000 on the housing programme, was there not? It was never made. It was necessary for me at that time to use what everybody always said were bad tactics upon my part - I had to manœuvre, and I did manœuvre and saved the 25,000 houses and the prescription charge. I say, therefore, to my right hon. and hon. Friends, there is no justification for taking this line at all. There is no justification in the arithmetic, there is less justification in the economics, and I beg my right hon. and hon. Friends to change their minds about it.

I say this, in conclusion. There is only one hope for mankind - and that is democratic Socialism. There is only one party in Great Britain which can do it - and that is the Labour Party. But I ask them carefully to consider how far they are polluting the stream. We have gone a long way - a very long way - against great difficulties. Do not let us change direction now. Let us make it clear, quite clear, to the rest of the world that we stand where we stood, that we are not going to allow ourselves to be diverted from our path by the exigencies of the immediate situation. We shall do what is necessary to defend ourselves - defend ourselves by arms, and not only with arms but with the spiritual resources of our people.