On this day on 18th April

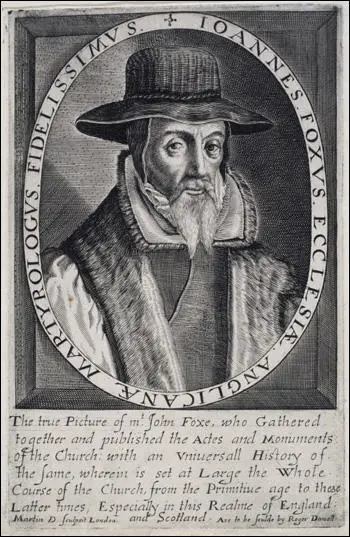

On this day in 1587 John Foxe died, at his house in Grub Street, London. John Foxe was born at Boston, Lincolnshire, in about 1516. His father died when he was young and his mother subsequently married Richard Melton, a prosperous yeoman of the nearby village of Coningsby. In 1534 he entered Brasenose College.

While at Oxford University he became a supporter of the ideas of Martin Luther and his opposition to the selling of pardons by Pope Leo X. As Foxe later explained: "In 1516 Pope Leo X began selling pardons, by which he gained a large amount of money from people who were eager to save the souls of their loved ones. His collectors assured the people that for every ten shillings they gave, one specified soul would be delivered from the pains of purgatory."

While at university he was a witness to the burning of William Cowbridge in September 1538 for being involved in the publishing of the Bible in the English language. "The fruitful seed of the gospel at this time had taken such root in England, that now it began manifestly to spring and show itself in all places, and in all sorts of people, as it may appear in this good man Cowbridge; who, coming of a good stock and family, whose ancestors, even from Wickliff's time hitherto, had been always favourers of the gospel, and addicted to the setting forth thereof in the English tongue... At that time Dr. Smith and Dr. Cotes governed the divinity schools, who, together with other divines and doctors, seemed not in this point to show the duty which the most meek apostle requireth in divines toward such as are fallen into any error, or lack instruction or learning."

John Foxe was elected fellow of Magdalen College in July 1539 and became one of the college lecturers in logic. He was strongly opposed to the idea that priests should not marry. A college statute required every fellow to take priest's orders. He was unwilling to do this. In a letter to one friend he explained that he could not remain at Magdalen "unless I castrate myself and leap into the priestly caste". To another friend he declared that "I do not intend to be circumcised this year".

John Foxe became highly critical of the Church during the reign of Henry VIII. "By reading this history, a person should be able to see that the religion of Christ, meant to be spirit and truth, had been turned into nothing but outward observances, ceremonies, and idolatry. We had so many saints, so many gods, so many monasteries, so many pilgrimages. We had too many churches, too many relics (true and fake), too many untruthful miracles. Instead of worshipping the only living Lord, we worshipped dead bones; in place of immortal Christ, we worshipped mortal bread. No care was taken about how the people were led as long as the priests were fed. Instead of God's Word, man's word was obeyed; instead of Christ's testament, the pope's canon. The law of God was seldom read and never understood, so Christ's saving work and the effect on man's faith were not examined. Because of this ignorance, errors and sects crept into the church, for there was no foundation for the truth that Christ willingly died to free us from our sins - not bargaining with us but giving to us."

After leaving university he stayed with Hugh Latimer, the Bishop of Worcester. Eventually Foxe secured a position as tutor in the household of Sir William Lucy, one of Latimer's friends, at Charlecote, Warwickshire. There he married Agnes Randall on 3rd February 1547. The couple moved to Stepney and over the next few years they had six children. During this period he began translating and publishing the sermons of Martin Luther. Simeon Foxe, later claimed that his father worked as a tutor to the children of Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey. Foxe's pupils were Surrey's three eldest children, Thomas, Jane and Henry. Foxe taught them at Mountjoy House, the Duchess of Richmond's London residence.

After the execution of her friend Anne Askew on 16th July 1546, Joan Bocher, an Anabaptist, began distributing pamphlets, and expressed the opinion that Christ, the perfect God, had not been born as a man to the Virgin Mary. She was arrested and brought to trial before Bishop Nicholas Ridley and found guilty of heresy. Boucher's views upset both Catholics and Protestants. John Rogers, who had been involved in the publishing of English Bible that had been translated by William Tyndale, was brought in to persuade her to recant. After failing in his mission he declared that she should be burnt at the stake.

John Foxe, who had been active in opposing the burning of heretics during the reign of Henry VIII was very distressed that Joan Bocher was now to be burned under the Protestant government of Edward VI. Although he disagreed with her views he thought that the life of "this wretched woman" should be spared and suggested that a better way of dealing with the problem was to imprison her so that she could not propagate her beliefs. Rogers insisted that she must die. Foxe replied she should not be burned: "at least let another kind of death be chosen, answering better to the mildness of the Gospel." Rogers insisted that burning alive was gentler than many other forms of death. Foxe took Rogers' hand and said: "Well, maybe the day will come when you yourself will have your hands full of the same gentle burning."

It has been claimed by Christian Neff that the 12-year-old King Edward at first refused to sign the death warrant. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer insisted that "she should be punished with death for her heresy according to the law of Moses".He is said to have told Cranmer with tears, "Cranmer, I will sign the verdict at your risk and responsibility before God’s judgment throne." Cranmer was deeply impressed, and he tried once more to induce her to recant but she still refused.

Joan Bocher was burnt at Smithfield on 2nd May 1550. "She died still upbraiding those attempting to convert her, and maintaining that just as in time they had come to her views on the sacrament of the altar, so they would see she had been right about the person of Christ. She also asserted that there were a thousand Anabaptists living in the diocese of London."

In 1551 John Foxe published De Censura. The book called for the revival of a system of ecclesiastical discipline and for a new code of canon law. Foxe claimed that he had the support of both Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Nicholas Ridley. Foxe also argued that adultery should not be a capital crime. This created a great deal of controversy. While Foxe had argued against imposing the death penalty on adulterers, he had also recommended that clerical sanctions, including excommunication, should be imposed on them.

When Mary I came to the throne Foxe and his wife fled to Europe. He eventually settled in Frankfurt where he wrote about the persecution of religious reformers in the 14th century such as John Wycliffe. This material eventually appeared in his book, Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563): "Wycliffe, seeing Christ's gospel defiled by the errors and inventions of these bishops and monks, decided to do whatever he could to remedy the situation and teach people the truth. He took great pains to publicly declare that his only intention was to relieve the church of its idolatry, especially that concerning the sacrament of communion."

Foxe's friends who remained in England were soon arrested. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer was put on trial for heresy on 12th September 1555. According to Jasper Ridley, the author of Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002): "Cranmer gave a piteous exhibition; he was utterly broken by his imprisonment, by the humiliations heaped upon him, and by the defeat of all his hopes; and the fundamental weakness in his character, his hesitations and his doubts were clearly displayed. But he steadfastly refused to recant and to acknowledge Papal Supremacy. He was condemned as a heretic."

On 16th October, Cranmer was forced to watch his friends, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, burnt at the stake for heresy. "It is reported that he fell to his knees in tears. Some of the tears may have been for himself. He had always given his allegiance to the established state; for him it represented the divine rule. Should he not now obey the monarch and the supreme head of the Church even if she wished to bring back the jurisdiction of Rome? In his conscience he denied papal supremacy. In his conscience, too, he was obliged to obey his sovereign."

Cranmer was guarded by Nicholas Woodson, a devout Catholic, who attempted to persuade him to change his views. It has been claimed that this friendship came to be his only emotional support, and, to please Woodson, he began giving way to everything that he had hated. On 28th January, 1556, he signed his first hesitant submission to papal authority. This was followed by submissions on 14th, 15th and 16th February. On 24th February he was made aware that his execution would take place in a few days time. In an attempt to save his life, he signed a statement that was truly a recantation. He probably did not write it himself; the Catholic commentary on it merely says that Cranmer was ordered to sign it.

Despite these recantations, Queen Mary I refused to pardon him and ordered Thomas Cranmer to be burnt at the stake. When he was told the news he probably remembered what Henry VIII said to him when he successfully persuaded the king not to execute his daughter. According to Ralph Morice Henry warned Cranmer that he would live to regret this action.

On 21st March, 1556, Thomas Cranmer was brought to St Mary's Church in Oxford, where he stood on a platform as a sermon was directed against him. He was then expected to deliver a short address in which he would repeat his acceptance of the truths of the Catholic Church. Instead he proceeded to recant his recantations and deny the six statements he had previously made and described the Pope as "Christ's enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine." The officials pulled him down from the platform and dragged him towards the scaffold.

Cranmer had said in the Church that he regretted the signing of the recantations and claimed that "since my hand offended, it will be punished... when I come to the fire, it first will be burned." According to John Foxe: "When he came to the place where Hugh Latimer and Ridley had been burned before him, Cranmer knelt down briefly to pray then undressed to his shirt, which hung down to his bare feet. His head, once he took off his caps, was so bare there wasn't a hair on it. His beard was long and thick, covering his face, which was so grave it moved both his friends and enemies. As the fire approached him, Cranmer put his right hand into the flames, keeping it there until everyone could see it burned before his body was touched." Cranmer was heard to cry: "this unworthy right hand!"

It was claimed that just before he died Cranmer managed to throw the speech he intended to make in St Mary's Church into the crowd. A man whose initials were J.A. picked it up and made a copy of it. Although he was a Catholic, he was impressed by Cranmer's courage, and decided to keep it and it was later passed on to John Foxe, who later published it. Jasper Ridley has argued that as a propaganda exercise, Cranmer's death was a disaster for Queen Mary. "An event which has been witnessed by hundreds of people cannot be kept secret and the news quickly spread that Cranmer was repudiated his recantations before he died. The government then changed their line; they admitted that Cranmer had retracted his recantations were insincere, that he had recanted only to save his life, and that they had been justified in burning him despite his recantations. The Protestants then circulated the story of Cranmer's statement at the stake in an improved form; they spread the rumour that Cranmer had denied at the stake that he had ever signed any recantations, and that the alleged recantations had all been forged by King Philip's Spanish friars."

In 1557 John Foxe and his growing family moved to Basel. He worked for printer Hieronymus Froben as a translator and proof reader. During this period he became friends with several continental protestant scholars. with much the greatest influence on Foxe's work was Matthias Flacius, who had written several books on early Church history. (20)

While in exile Foxe worked on his history of Christian martyrdom. In August 1559 he published Foxe's Book of Martyrs in Latin. The first section dealt was entitled "Persecution of the Early Christians". Another section looked at at the persecution of Protestants in Europe during the Middle Ages. However, most of the book covered the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary I. It was largely based on history books by people such as Edward Hall and John Bale.

Queen Elizabeth appeared to be a more tolerant monarch and in Foxe decided to return to England in October 1559. He travelled around the country speaking to the survivors, to the friends of the victims and the the people who had witnessed heretics being burnt at the stake. He also made copies of letters written by martyrs to family and friends, while they waited in prison for their executions. Foxe also looked at the official records of their interrogations. Foxe was very concerned with providing a factual record of the names, occupations, age, and the town or village of origin of the martyrs.

In 1563 Foxe published the first English edition of Foxe's Book of Martyrs. It included all the passages that he had already published in Latin, plus all the new material he had collected about the martyrs under Mary. The book had 1,721 pages and ran to 1,450,000 words. It was dedicated to the "most Christian and renowned princess, Queen Elizabeth". After the book was published, many people wrote to Foxe. Some pointed out minor errors in his book. Some gave him information which he had so far been unable to find. This material was included in the second edition published in 1570. This edition had 2,335 pages and 3,150,000 words. It was nearly four times the length of the Bible, and according to Jasper Ridley was the "longest single work which has ever been published in the English language."

Thomas S. Freeman has pointed out that the book made good use of the library accumulated by Archbishop Matthew Parker. "Foxe's second edition also far surpassed any previous English historical work in the range of medieval chronicles and histories on which it was based. Foxe had the immense good fortune to be able to consult the vast collection of historical manuscripts gathered by Archbishop Matthew Parker. Although the primate and the martyrologist had their differences, which later became manifest, Parker saw an opportunity to use Foxe's Acts and Monuments to demonstrate his own interpretation of history in which an apostolic English church was corrupted by the papacy, in a process that began with Augustine of Canterbury's mission and became more virulent as foreign bishops like Lanfranc and Anselm were foisted on the English church after 1066. This in turn led to the establishment in the English church of such popish ‘abuses’ as transubstantiation, clerical celibacy, and auricular confession."

It has been argued that the Foxe's Book of Martyrs is one of the most important books published in the English language: "The Book of Martyrs, with the full force of government propaganda behind it, undoubtedly had a powerful effect on the English people, and is one of the few books which can be said to have changed the course of history."

In 1573 John Foxe edited a collection of the works of William Tyndale, Robert Barnes and John Frith. Foxe admitted that his main objective was to use logical and theological arguments, supported by historical examples, which would induce Catholics and Jews to abandon their "superstitions" and embrace the gospel. In the introduction he expressed the hope that those who "be not yet won to the word of truth, setting aside all partiality and prejudice of opinion, would with indifferent judgements, bestow some reading and hearing likewise of these three authors."

In the spring of 1575 a congregation of Anabaptist was discovered in Aldgate. They were arrested and charged with advocating that infants should not be baptized, that a Christian should neither be a magistrate or a soldier. Five recanted and another fifteen were deported. However, the group's two leaders, John Weelmaker and Henry Toorwoort were condemned to death by burning.

John Foxe took up their case and wrote to Queen Elizabeth pointing out that no burnings had taken place for seventeen years. "I have no favour for heretics, but I am a man and would spare the life of a man. To roast the living bodies of unhappy men, erring rather from blindness of judgement than from the impulse of will, in fire and flames, of which the fierceness is fed by the pitch and brimstone poured over them, in a Romish abomination... for the love of God spare their lives." Elizabeth rejected the request for mercy and they were both burnt at Smithfield.

Thomas S. Freeman points out that his deep abhorrence of the death penalty should not be confused with toleration of Anabaptist beliefs. "Foxe despised the Anabaptists' doctrines and was determined to eradicate such heresies from England. He approved of the banishment of the Anabaptists and urged exile, imprisonment, flogging, or branding as alternatives to execution. Most importantly, his fundamental argument for sparing the lives of the Anabaptists was his conviction that, if they were given enough time, they could be persuaded to recant their errors. Along with Foxe's determination to eliminate false religion went a profound conviction that it should, and could, be eliminated by persuasion rather than by force."

Francis Walsingham and William Cecil decided that Foxe's Book of Martyrs, could be used in the anti-Catholic propaganda campaign deployed in the 1580s against Mary, Queen of Scots and her supporters. A copy was placed in every cathedral and most churches. The English captains of the ships that sailed to the West Indies and South America to raid and plunder the Spanish towns there and to fight the Spaniards at sea, were ordered to have a copy of the book in the ship. All the English ships involved in defeating the Spanish Armada carried a copy of the book. It was argued that "their crews believed that they were fighting to save their country from a repetition of the horrors of Mary's reign if the Spaniards succeeded in invading and conquering England."

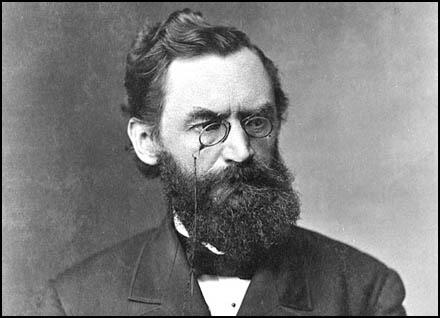

On this day in 1802 Erasmus Darwin died. Erasmus Darwin, the seventh child of Robert Darwin and Elizabeth Hill Darwin, was born on 12th December 1731. His father was a lawyer who came from a wealthy family. He was sent to the Chesterfield School in 1741 and in 1750 became a student at St John's College, where he studied classics and mathematics.

After leaving Cambridge University he studied medicine in Edinburgh which was, at that time, a major centre for medical education in Europe. Darwin established his first medical practice in Nottingham in 1756 but soon afterwards moved to Lichfield. The following year he married Mary Howard and over the next few years had three children, Charles, Erasmus and Robert.

Anna Seward met Darwin for the first time in 1757. "Dr. Darwin... was inclined to corpulence; his limbs too heavy for exact proportion... Florid health, and the earnest of good humour, a sunny smile, on entering a room, and on first accosting his friends, rendering, in his youth, that exterior agreeable, to which beauty and symmetry had not been propitious. He stammered extremely; but whatever he said, whether gravely or in jest, was always worth waiting for, though the inevitable impression it made might not always be pleasant to individual self-love". Another source commented on his "pock-marked face" and "stooping shoulders" that made him "look twice his age".

While living in Litchfield he became friends with Matthew Boulton, the owner of a company in Birmingham that employed 20,000 people. At his Soho Manufactory, considered to be Britain's very first factory made small metal goods such as "gold and silver toys produced trinkets, snuff-boxes, inkstands... and steel toys, chiefly buckles for both shoes and knee-breeches".

Jenny Uglow, the author of The Lunar Men (2002), suggested that "The chief bond between them was the love of invention and experiment. Very quickly they realized how they could complement each other. Darwin the university-educated theorist, Boulton the man with the technical know-how. equally outspoken, energetic and ebullient, they were two sides of a coin."

Erasmus Darwin was interested in natural philosophy and mechanical invention. In 1757 he published a paper where he provided details of an experiment that he carried out which proved that electricity did not affect the mechanical properties of air. A second paper, on his treatment of a patient who was spitting up blood, was published in Philosophical Transactions in 1760. The following year Darwin became a fellow of the Royal Society.

In 1768 Darwin and Boulton formed what became known as the Lunar Society of Birmingham. Other members included Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley, James Brindley, Thomas Day, William Small, John Whitehurst, John Robison, Joseph Black, William Withering, John Wilkinson, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Joseph Wright. This group of scientists, writers and industrialists discussed philosophy, engineering and chemistry.

As Maureen McNeil has pointed out: "These innovating men of science and industry were drawn together by their interest in natural philosophy, technological and industrial development, and social change appropriate to these concerns. The society acquired its name because of the practice of meeting once a month on the afternoon of the Monday nearest the time of the full moon, but informal contacts among members were also important."

Boulton's factory used machines performing tasks such as turning lathes and stamping sheet metal. The engines of these machines were driven by a water mill, but the water source was always running dry, either from drought or diversion to the Birmingham Canal. Boulton and some of his friends at the Lunar Society had many discussions about the possibility of developing an engine powered by steam. Darwin was especially involved in these experiments but he had to admit that he was unable to overcome the problems that Boulton faced.

James Watt, eventually came up with an effective steam-engine. Watt and Boulton formed a new company together. Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character.... Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm."

Darwin continued his work as a doctor and scientist. He kept a book in which he recorded medical case notes, reflected on meteorology, and made mechanical designs of spinning machines, water pumps, and canal locks. "A keen inventor, among his many other mechanical contrivances were a new steering mechanism for carriages, a copying machine, and even a mechanical bird". He also developed a mechanical copying machine and sent the first duplicated letter to the politician Charles Greville.

Darwin had always written poetry and he formed a small literary circle in Lichfield. This included Anna Seward, Thomas Day, and Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Another reason for his poetry writing during this period was his love for Elizabeth Pole, who was not only beautiful but married, and therefore unobtainable. Darwin was almost thirty years older that Elizabeth who was in her late twenties. Elizabeth was described as having "agreeable features; the glow of health; a fascinating smile; a fine form, tall and graceful; playful sprightliness of manners; a benevolent heart and maternal affection."

Mary Darwin became unwell. According to William Small she became much worse in February 1769. (14) She had attacks of violent pain in her head and on her right side, near her liver. Darwin prescribed opium but the more she took the less effect it had and she began supplementing it with wine and brandy. It was claimed she was often drunk and delirious. Mary told her husband that it was "hard so early in life to leave her children and her husband she loved so much - pray take care of yourself and them".

Mary Darwin died on 30th June 1770. He wrote few letters following his wife's death and stopped doing scientific experiments. A month later he employed the seventeen-year-old Mary Parker to look after his four-year-old son, Robert. Parker became his mistress and she gave birth to Susan in May 1772. Mary was born two years later. However, he never married Mary. As Jenny Uglow pointed out: "however liberal his views, class seemingly ruled out the possibility of marriage".

Darwin was an expert on, and advocate of, technological innovation. He recognized the need for good transport systems to facilitate industrialization and, as well as designing canal lifts, he campaigned for canals. This included the Trent & Mersey Canal. The canal began within a few miles of the River Mersey, near Runcorn and finished in a junction with the River Trent in Derbyshire. It is just over ninety miles long with more than 70 locks and five tunnels. At the time it was described as the "greatest civil engineering work built in Britain."

On 27th November 1780, Elizabeth Pole's 63-year-old husband died. She was "thirty-three, dashing, witty and rich: half the young men in the country were after her". Darwin, who was "forty-nine, stout, stuttering and lame, with two grown sons, and two illegitimate daughters" appeared to have little chance as she had told a friend that he was "too old for me". However, despite this objection, she married Darwin on 6th March 1781. In the spring of 1782 Darwin and Elizabeth had their first child, Edward: three more boys and three girls followed over the next eight years.

The first volume of what Darwin described as his medico-philosophical work, Zoonomia: The Laws of Organic Life, appeared in 1794. (19) Drawing on the work of his great friend, Joseph Priestley, the book offered a theory of biological learning which included both mind and body. "Opposed to notions of innate ideas, Darwin showed that ideas resulted from mental development through habits, often based on imitation. Hence he attributed the link between the wavy line and the sense of beauty, proposed by William Hogarth, to the infant's experience of the mother's breast. Darwin's contribution to associationist psychology was to sketch a sequential development of the faculties, through animal interaction with their environment, that fully integrated body and mind: from simple irritative responses to those of volition and association".

The second volume of Zoonomia: The Laws of Organic Life appeared in 1796. It included a catalogue of diseases, classified according to their proximate causes, together with details of substances for use in medical treatment. This included Priestley's recommendation that carbonated water would help people suffering from kidney stones. (10a) The book also included a chapter where he "formulated a theory of the development of life, free from the guiding hand of the Creator". It has been argued by his biographer, Desmond King-Hele, that "too old and hardened to fear a little abuse" he was no longer cowed by the wrath of his religious friends.

Erasmus Darwin wrote: "Would it be too bold to imagine that in the great length of time since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind, would it to be too bold to imagine that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which the great first cause endowed with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts, attended with new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions and associations; and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity; and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity, world without end!"

Members of the Lunar Society were radical reformers. They supported freedom of the press, religious toleration, parliamentary reform and opposed the slave-trade. Darwin also welcomed the French Revolution. the challenging of the old order in France. Conservatives like Edmund Burke regarded their views as "insidious and foreign". In July 1791, Darwin's close friend, Joseph Priestley, had his house burnt down and his scientic equipment destroyed by anti-radical mob. Darwin was subjected to political attacks by George Canning and others in the conservative press. Other writers accused Darwin of holding "atheistic opinions".

On this day in 1812 Archibald Prentice reports on the Luddite disturbances in Manchester. "On Saturday, the 18th April, a numerous body of women, chiefly women, assembled at the potato market, Shude Hill, where the sellers were asking 14s. and 15s. per load (252 lbs.) for potatoes. Some of the women began forcibly to take possession of the articles; but the civil and military power interposing, to fix a sort of maximum, for eight shillings per load, at which they were sold in small portions. On Monday a cart carrying fourteen loads of meal was stopped, and the meal carried away. On 27th April a riotous assembly took place at Middleton. The weaving factory of Mr. Burton and Sons had been previously threatened in consequence of their mode of weaving being done by the operation of steam. The factory was protected by soldiers, so strongly as to be impregnable to their assault; they then flew to the house of Mr. Emanuel Burton, where they wreaked their vengeance by setting it on fire. On Friday, the 24th April, a large body of weavers and mechanics began to assemble about midday, with the avowed intention of destroying the power-looms, together with the whole of the premises, at Westhoughton. The military rode at full speed to Westhoughton; and on their arrival were surprised to find that the premises were entirely destroyed, while not an individual could be seen to whom attached any suspicion of having acted a part in this truly dreadful outrage."

In the early months of 1811 the first threatening letters from General Ned Ludd and the Army of Redressers, were sent to employers in Nottingham. Workers, upset by wage reductions and the use of unapprenticed workmen, began to break into factories at night to destroy the new machines that the employers were using. In a three-week period over two hundred stocking frames were destroyed. In March, 1811, several attacks were taking place every night and the Nottingham authorities had to enroll four hundred special constables to protect the factories. To help catch the culprits, the Prince Regent offered £50 to anyone "giving information on any person or persons wickedly breaking the frames". These men became known as "Luddites".

Luddism spread to other parts of the country. Throughout 1812 there were attacks on Lancashire cotton mills using power looms. On 20th March, 1812 the warehouse of William Radcliffe, one of the first manufacturers to use the power-loom, was attacked by a group of Luddites in Stockport. The Manchester Gazette reported: "On Monday afternoon a large body, not less than 2,000, commenced an attack, on the discharge of a pistol, which appeared to have been the signal; vollies of stones were thrown, and the windows smashed to atoms; the internal part of the building being guarded, a musket was discharged in the hope of intimidating and dispersing the assailants. In a very short time the effects were too shockingly seen in the death of three, and it is said, about ten wounded."

This was followed by attacks on Burton's Mill at Middleton near Manchester and the burning down of Emanuel Burton's home. The Leeds Mercury reported: "A body of men, consisting of from one to two hundred, some of them armed with muskets with fixed bayonets, and others with colliers' picks, who marched into the village in procession, and joined the rioters. At the head of the armed banditti a man of straw was carried, representing the renowned General Ludd whose standard bearer waved a sort of red flag".

In February 1812 the government of Spencer Perceval proposed that machine-breaking should become a capital offence. Lord Byron made a speech in the House of Lords on the subject of machine-breaking. "During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the the county I was informed that forty Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection.... But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community."

Byron went on to argue that it was wrong to make machine-breaking a capital offence: "As the sword is the worst argument than can be used, so should it be the last. In this instance it has been the first; but providentially as yet only in the scabbard. The present measure will, indeed, pluck it from the sheath; yet had proper meetings been held in the earlier stages of these riots, had the grievances of these men and their masters (for they also had their grievances) been fairly weighed and justly examined, I do think that means might have been devised to restore these workmen to their avocations, and tranquillity to the country."

Despite the warnings made by Byron, Parliament passed the Frame Breaking Act that enabled people convicted of machine-breaking to be sentenced to death. As a further precaution, the government ordered 12,000 troops into the areas where the Luddites were active. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) suggested that "masses of workers were coming to realise as the result of ferocious class legislation... that the state apparatus was in the hands of their oppressors."

Throughout 1812 there were attacks on Lancashire cotton mills using power looms. On 20th March, 1812 the warehouse of William Radcliffe, one of the first manufacturers to use the power-loom, was attacked by a group of Luddites in Stockport. The Manchester Gazette reported: "On Monday afternoon a large body, not less than 2,000, commenced an attack, on the discharge of a pistol, which appeared to have been the signal; vollies of stones were thrown, and the windows smashed to atoms; the internal part of the building being guarded, a musket was discharged in the hope of intimidating and dispersing the assailants. In a very short time the effects were too shockingly seen in the death of three, and it is said, about ten wounded."

Wheat prices soared in 1812. Unable to feed their families, workers became desperate. On 20th April several thousand men attacked Burton's Mill at Middleton near Manchester. Emanuel Burton, who knew that his policy of buying power-looms had upset local handloom weavers, had recruited armed guards and three members of the crowd were killed by musket-fire. The following day the men returned and after failing to break-in to the mill, they burnt down Emanuel Burton's house. The military arrived and another seven men were killed.

The Leeds Mercury reported: "A body of men, consisting of from one to two hundred, some of them armed with muskets with fixed bayonets, and others with colliers' picks, who marched into the village in procession, and joined the rioters. At the head of the armed banditti a man of straw was carried, representing the renowned General Ludd whose standard bearer waved a sort of red flag".

Three days later, Wray & Duncroff's Mill at Westhoughton, near Manchester, was set on fire. William Hulton, the High Sheriff of Lancashire, arrested twelve men suspected of taking part in the attack. Four of the accused, Abraham Charlston, Job Fletcher, Thomas Kerfoot, and James Smith, were executed. The Charlston's family claimed Abraham was only twelve years old but he was not reprieved. It was reported that Abraham cried for his mother on the scaffold. A local part-time journalist, John Edward Taylor, investigated the case and claimed that the attack had been the result of action taken by spies employed by Colonel Fletcher, one of Manchester's magistrates.

On of the most serious Luddite attacks took place at Rawfolds Mill near Brighouse in Yorkshire. William Cartwright, the owner of Rawfolds Mill, had been using cloth-finishing machinery since 1811. Local croppers began losing their jobs and after a meeting at Saint Crispin public house, they decided to try and destroy the cloth-finishing machinery at Rawfolds Mill. Cartwright was suspecting trouble and arranged for the mill to be protected by armed guards.

Led by George Mellor, a young cropper from Huddersfield, the attack on Rawfolds Mill took place on 11th April, 1812. The Luddites failed in gain entry and by the time they left, two of the croppers had been mortally wounded. Seven days later the Luddites killed William Horsfall, another large mill-owner in the area. The authorities rounded up over a hundred suspects. Of these, sixty-four were indicted. Three men were executed for the murder of Horsfall and another fourteen were hung for the attack on Rawfolds Mill.

In the summer of 1812 eight men in Lancashire were sentenced to death and thirteen transported to Australia for attacks on cotton mills. In June John Knight and thirty-seven handloom weavers were arrested in a a public house in Manchester by Joseph Nadin. Knight was charged with "administering oaths to weavers pledging them to destroy steam looms" and they were accused of attending a seditious meeting. At their subsequent trial all thirty-eight were acquitted. "The effects of this ill-advised prosecution," commented Archibald Prentice, "were long and injuriously felt... as it introduced that bitter feeling of employed against employers".

In 1813 several court cases took place to deal with the Luddites. There were 28 convictions (including eight sentenced to death and thirteen to transportation) at Chester. Fifteen Luddites were executed at York. The judge told the prisoners: "You have been guilty of one of the greatest outrages that ever was committed in a civilized country... It is of infinite importance... that no mercy should be shown to any of you... and the sentence of the law... should be very speedily executed."

By 1815 handloom weavers were having great problems finding enough work. Manchester's 40,000 handloom weavers found it extremely difficult to compete with power looms. In an attempt to earn a living they sold their cloth at a lower price than that being produced by the local factories. As a result, the average wage of a handloom weaver fell from 21s in 1802 to less than 9s in 1817.

Further sporadic outbreaks of violence but by 1817 the Luddite movement had ceased to be active in Britain. However, weavers continued to suffer from the introduction of new machines. A weaver from Bury wrote: "A weaver is no longer able to provide for the wants to a family. We are shunned by the remainder of society and branded as rogues because we are unable to pay our way. If we apply to the shopkeeper, tailor, shoemaker, or any other tradesman for a little credit, we are told that we are unworthy of it, and to trust us would be dangerous."

On this day in 1828 cartoonist Frank Bellew, the son of a British officer, was born in India. After spending his youth in England he moved to New York City in 1850.

Bellew worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for a variety of different journals including Frank Leslie's Illustrated, Harper's Weekly, Scribner's Magazine, and Puck Magazine. Bellew also published a book, The Art of Amusing (1866).

Charles Dickens commented that: "Frank Bellew's pencil is extraordinary. He probably originated more, of a purely comic nature, than all the rest of the artistic brethren put together." Drawings of Abraham Lincoln that exaggerated his height, were particularly popular. Frank Bellew died on 29th June, 1888.

On this day in 1859 Carl Schurz makes important speech on civil rights of the Republican Party in Massachusetts.

I wish the words of the Declaration of Independence, "that all men are created free and equal, and are endowed with certain inalienable rights," were inscribed upon every gatepost within the limits of this republic. From this principle the revolutionary fathers derived their claim to independence; upon this they founded the institutions of this country; and the whole structure was to be the living incarnation of this idea.

Shall I point out to you the consequences of a deviation from this principle? Look at the slave states. This is a class of men who are deprived of their natural rights. But this is not the only deplorable feature of that peculiar organization of society. Equally deplorable is it that there is another class of men who keep the former in subjection. That there are slaves is bad; but almost worse is that there are masters.

Are not the masters freemen? No, sir! Where is their liberty of the press? Where is their liberty of speech? Where is the man among them who dares to advocate openly principles not in strict accordance with the ruling system? They speak of a republican form of government, they speak of democracy; but the despotic spirit of slavery and mastership combined pervades their whole political life like a liquid poison. They do not dare to be free lest the spirit of liberty become contagious.

The system of slavery has enslaved them all, master as well as slave. What is the cause of all this? It is that you cannot deny one class of society the full measure of their natural rights without imposing restraints upon your own liberty. If you want to be free, there is but one way - it is to guarantee an equally full measure of liberty to all your neighbors.

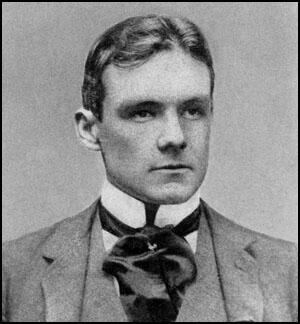

On this day in 1864 journalist Richard Harding Davis, the son of two writers, was born in Philadelphia. After an education at the Episcopal Academy and Johns Hopkins University, he became a journalist. His first job was as a reporter for the Philadelphia Press. In 1888 he moved to the New York Sun and by the age of 26 he was the managing editor of Harper's Weekly.

Davis covered the Spanish War, the Spanish-American War in Cuba, the Greco-Turkish War and the Boer War. As well as articles he wrote several books about his travels, including Rulers of the Mediterranean (1894), About Paris (1895) and Three Gringos in Venezuela and Central America (1896).

By the outbreak of the First World War, Davis was the most experienced and respected war correspondent in America. He was also the best rewarded with the Wheeler syndicate paying him $32,000 a year to report the war in Europe. Captured by the German Army in Belgium in 1914, he was threatened with execution as a British spy as his passport had been issued in London and not Washington. Eventually Davis was able to convince the Germans he was an American reporter and he was released.

Harding remained in Europe until 1915, but was unhappy with the restrictions imposed on him by the Allied authorities. Before returning to America he was quoted as saying he was not staying "to write sidelights". Richard Harding Davis died on 11th April 1916.

On this day in 1867, the executive council of the Reform League met in London and unanimously condemned the proposed 1867 Reform Act as "partial and oppressive" and reaffirmed their commitment to "a vote for a man because he is a man". Charles Bradlaugh called for a national demonstration to take place in Hyde Park. It was pointed out that this would be breaking the law but Bradlaugh's motion was passed by five votes to three. The following day placards started to go up all over the country announcing a mass demonstration for universal manhood suffrage on 6th May.

Spencer Walpole, the Home Secretary, announced that attending such a meeting would be illegal and that "all persons are hereby warned and admonished that they will attend any such meeting at their peril, and all her Majesty's loyal and faithful subjects are required to abstain from attending, aiding or taking part in any such meeting, or from entering the Park with a view to attend, aid or take part in any such meeting."

The Government arranged for troops of Hussars to be deployed in the park and thousands of special constables were sworn in. However, so many demonstrators turned up it was decided to back down. "As always with such demonstrations, versions of the numbers varied hugely - from 20,000 in some Tory papers to 500,000 in the League accounts. Some proof that the latter figure was closer to the reality came from the 14 separate platforms from which the most accomplished speakers could not make themselves heard."

It was the first time that any political organization representing the working class had openly and successfully defied the law. Bradlaugh commented that the reformers who had been killed at Peterloo were now at last victorious. The newspapers called for the arrests of the leaders of the Reform League. The government decided that this would be too dangerous and instead, Walpole, the Home Secretary, resigned.

Benjamin Disraeli realised that he had to make his Reform Bill more popular with the working class. On 20th May he accepted an amendment from Grosvenor Hodgkinson, which added nearly half a million voters to the electoral rolls, therefore doubling the effect of the bill. Gladstone commented: "Never have I undergone a stronger emotion of surprise than when, as I was entering the House, our Whip met me and stated that Disraeli was about to support Hodgkinson's motion."

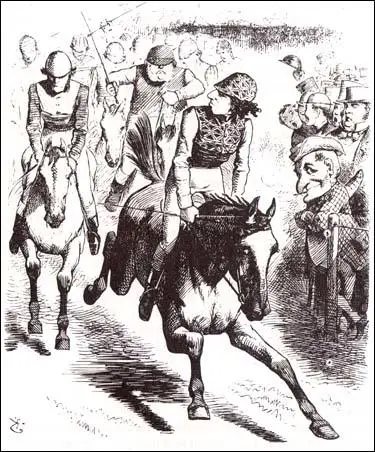

"The Derby, 1867, Dizzy wins with Reform Bill"

John Tenniel, Punch Magazine (25th May, 1867)

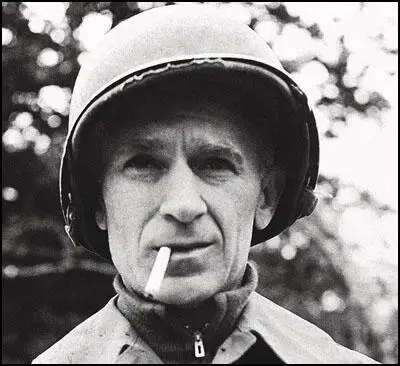

On this day in 1945 Ernie Pyle is killed by a Japanese sniper while on a routine patrol. Ernie Pyle, the son of a farmer, was born in 1900. After studying journalism at Indiana University he found work on a small newspaper in La Porte, Indiana. In 1923 he moved to the Washington Daily News and eventually became the paper's managing editor.

In 1932 he was commissioned to write a travel column for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. He did this until the outbreak of the Second World War when he became a war correspondent. He moved to England in 1940 where he reported on the Blitz for the New York World Telegram.

Pyle went with the US Army to North Africa in November 1942. This was followed by the invasions of Sicily and Italy. He also accompanied Allied troops during the Normandy landings and witnessed the liberation of France. By 1944 Pyle had established himself as one of the world's outstanding reporters and Time hailed him as "America's most widely read war correspondent."

John Steinbeck commented: "There is, the war of maps and logistics, of campaigns, of ballistics, armies, divisions, and regiments. Then there is the war of homesick, weary, funny, violent, common men, who wash their socks in their helmets, complain about food, whistle at Arab girls, or any other girls for that matter, and lug themselves through as dirty a business as the world has ever seen and do it with humanity and dignity and courage - and that is Ernie Pyle's war."

Pyle became disillusioned with the war and wrote to his wife: "Of course I am very sick of the war and would like to leave it, and yet I know I can't. I've been part of the misery and tragedy of it for so long that I feel if I left it, it would be like a soldier deserting."

In 1945 Ernie Pyle was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for journalism. Later that year he went with US troops to Okinawa.

On this day in 1946 Hans Frank, governor general of Poland, admits to his responsibility for the Holocaust. "In my own sphere I did everything that could possibly be expected of a man who believes in the greatness of his people and who is filled with fanaticism for the greatness of his country, in order to bring about the victory of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist movement. I never participated in far-reaching political decisions, since I never belonged to the circle of the closest associates of Adolf Hitler, neither was I consulted by Adolf Hitler on general political questions, nor did I ever take part in conferences about such problems. Proof of this is that throughout the period from 1933 to 1945 I was received only six times by Adolf Hitler personally, to report to him about my sphere of activities."

Hans Frank, who had recently converted to Roman Catholicism was found guilty of crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial and executed on 1st October, 1946.

On this day in 1946 Hermann Göring explained how the Nazis manipulated the masses. "Why, of course, the people don't want war. Why would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece. Naturally, the common people don't want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship... The people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country."

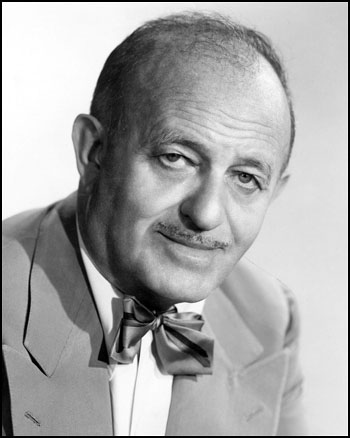

On this day in 1964 Ben Hecht died. Hecht, the son of Russian–Jewish immigrants, Joseph Hecht and Sarah Swernofsky Hecht, was born in New York City on 28th February, 1894. His parents, who worked in the garment industry, spoke Yiddish in the family home.

The family moved to Racine, Wisconsin, in order to run a store. As a child he was a talented violinist. However, he wanted to be a writer and at the age of sixteen he moved to Chicago. He found work as a journalist with the Chicago Journal. He later moved to the Chicago Daily News where he became friends with fellow reporter, Charles MacArthur. While living in the city he became friends with other aspiring writers such as Floyd Dell, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Carl Sandburg and Maxwell Bodenheim.

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Two days later, Emil Eichhorn was appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, ordered the removal of Eichhorn. When this order was rejected, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion.

Hecht was sent to Germany to report on what had become known as the German Revolution. This included the assassination of Kurt Eisner on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, leaders of the J were also murdered by the authorities. Hecht's first novel, Erik Dorn (1921) was based on events he observed in Germany in 1919.

In 1921, Hecht started a Chicago Daily News column called, One Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago . His editor, Henry Justin Smith, later argued that it was a new development in journalism "in this urban life there dwelt the stuff of literature, not hidden in remote places, either, but walking the downtown streets, peering from the windows of sky scrapers, sunning itself in parks and boulevards. He (Hecht) was going to be its interpreter. His was to be the lens throwing city life into new colors, his the microscope revealing its contortions in life and death."

Hecht also published short-stories in magazines such as The Little Review and The Smart Set. In 1926 his friend, Charles MacArthur had joined forces with Edward Sheldon, to write the play, Lulu Belle. The play was very controversial as it featured a prostitute played by Lenore Ulric, who bewitched powerful men in New Orleans. The play was a great success and MacArthur suggested to Hecht that they wrote a play together.

The play was produced by Jed Harris. However, he insisted that the play needed editing and gave the job to George S. Kaufman. As Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972), has pointed out: "The best cutter and the fastest rewriter in the theatre was George Kaufman. He took care of the gangsters. Futhermore, Hecht and MacArthur were newspapermen and so was Kaufman; the three of them spoke a common language. He finally joked and cajoled them into writing a better, tighter, funnier script." Kaufman was also recruited as director of the play.

The play, The Front Page, was a comedy about tabloid newspaper reporters covering the execution of Earl Williams, a white man and a suspected member of the American Communist Party who had been convicted of killing a black policeman. Williams is based on the case of Tommy O'Connor, who escaped from a Chicago courthouse in 1923. It opened at the Times Square Theatre on 14th August, 1928. The play was a smash hit, running 278 performances before closing in April 1929.

MacArthur and Hecht developed a reputation for hard-drinking. Howard Teichmann argues that this caused problems with the director of the play: "Stories of the wonderful wildness of Hecht and MacArthur persist in theatrical circles to this day. Kaufman, with his built-in sense of discipline, almost left the show. When he found them in a speakeasy, they would offer him a drink. Kaufman who took whiskey as though it were medicine managed to go through a lifetime of cocktail parties by quietly pouring his drinks into convenient receptacles."

Hecht now moved to Hollywood and provided the stories or wrote the screenplays for The Unholy Night (1929), Roadhouse Nights (1930), The Front Page (1930), The Unholy Garden (1931), Scarface (1932), Turn Back the Clock (1933), Design for Living (1933), Viva Villa! (1934), Upperworld (1934), Crime Without Passion (1934), Once in a Blue Moon (1935), Barbary Coast (1935), The Scoundrel (1935), Soak the Rich (1936), Nothing Sacred (1937), The Goldwyn Follies (1938), Gunga Din (1939), Wuthering Heights (1939), It's a Wonderful World (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Angels Over Broadway (1940), Comrade X (1940), Lydia (1941), The Black Swan (1941), China Girl (1942), Spellbound (1945), Notorious (1946), Whirlpool (1949), The Indian Fighter (1955), Miracle in the Rain (1956) and A Farewell to Arms (1957).