On this day on 15th April

On this day in 1053 Earl Godwin died. Godwin, the son of the late tenth-century renegade and pirate Wulfnoth Cild of Compton, West Sussex, who had rebelled against Ethelred the Unready, was born in about 1001. In 1009 Wulfnoth was accused of unspecified crimes at a muster of the fleet; he fled with twenty ships and a force sent to pursue him was destroyed in a storm.

Godwin was a strong supporter of King Cnut the Great, and in 1018 he was given the title of Earl of Wessex. Cnut commented that he found Godwin "the most cautious in counsel and the most active in war". He took him to Denmark, where he "tested more closely his wisdom", and "admitted him to his council". Cnut introduced him to Gytha. Her brother Ulf, was married to Cnut's sister.

Godwin married Gytha, in about 1020. She gave birth to a least six sons: Swein, Harold, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth; and three daughters: Edith, Gunhild and Elfgifu. The birth dates of the children are unknown.

During Harold's childhood his father held an important positioned, helping, along with Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, to govern England during the king's extended absences. In 1042, Godwin helped to arrange for Edward the Confessor, the seventh son of Ethelred the Unready, to become king. The following year Godwin's eldest son, Swein, became Earl of the South-West Midlands.

In 1045, Godwin's 20-year-old daughter, Edith, married 42-year-old Edward. Godwin hoped that his daughter would have a son but Edward had taken a vow of celibacy and it soon became clear that the couple would not produce an heir to the throne. Christopher Brooke, the author of The Saxon and Norman Kings (1963), has suggested that this story might have been made up as a part of the legend of royal piety, and as a delicate compliment to a queen who suffered from the common misfortune of failing to bear children."

Harold's older brother, Swein, lost support from his father and the king, when in 1046 he was sent into exile for seducing the abbess of Leominister. At this time Harold became Earl of Eastern England. The area extended across East Anglia, Essex, Huntingdonshire, and Cambridgeshire. During this period that Harold doubtless took as his concubine Edith Swanneck. Such relationships, in spite of increasing pressures from Church leaders were common. Harold and Edith had at least five children. This "Danish marriage", as contemporaries called it, "must have bound Harold closely through ties of kinship and marriage to many Anglo-Scandinavian lords settled in his earldom".

Edward the Confessor became concerned about the growth in power of Earl Godwin and his sons. According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward promised William of Normandy that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. Tostig moved to mainland Europe and married Judith of Flanders in the autumn of 1051. Harold and Leofwine went to seek help in Ireland. Earl Godwin, Swein and the rest of the family went to live in Bruges.

Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Queen Edith was removed from court. Jumièges urged Edward to divorce Edith, but he refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery. Edward also appointed other Normans to official positions. This caused great resentment amongst the English and many of them crossed the Channel to offer Godwin their support.

Godwin and his sons were furious by these developments and in 1052 they returned to England with a mercenary army. Edward was unable to raise significant forces to stop the invasion. Most of the men in Kent, Surrey and Sussex joined the rebellion. Godwin's large fleet moved round the coast and recruited men in Hastings, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich. He then sailed up the Thames and soon gained the support of Londoners.

Negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester. Robert left England and was declared an outlaw. Pope Leo IX condemned the appointment of Stigand as the new Archbishop of Canterbury but it was now clear that the Godwin family was back in control.

At a meeting of the King's Council, Godwin cleared himself of the accusations brought against him, and Edward restored him and his sons to land and office, and received Edith once more as his queen. Earl Swein did not return and instead set off from Bruges on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, "to look to the salvation of his soul". John of Worcester says that he walked barefoot all the way and that on the journey home he became ill and died in Lycia on 29th September 1052.

Godwin now forced Edward the Confessor to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. Earl Godwin died on 15th April, 1053. Some accounts say he choked on a piece of bread. Others say he was accused of being disloyal to Edward and died during an Ordeal by Cake. Another possibility is that he died from a stroke. His place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his eldest son, Harold.

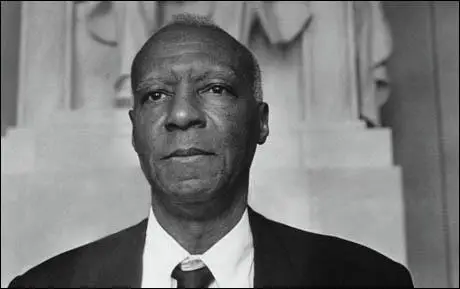

On this day in 1889 Asa Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City, Florida. The son of a Methodist minister, he was educated locally before moving to New York City where he studied economics and philosophy at the City College.

While in New York he worked as an elevator operator, a porter and a waiter. In 1917 Randolph founded a magazine, The Messenger (later the Black Worker), which campaigned for black civil rights. During the First World War he was arrested for breaking the Espionage Act. It was claimed that Randolph and his co-editor, Chandler Owen was guilty of treason after opposing African Americans joining the army.

After the war Randolph lectured at the Rand School of Social Science. A member of the Socialist Party, Randolph made several unsuccessful attempts to be elected to political office in New York. He was was involved in organizing black workers in laundries, clothes factories and cinemas and in 1929 became president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). Over the next few years he built it into the first successful black trade union.

The BSCP were members of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) but in protest against its failure to fight discrimination in its ranks, Randolph took his union into the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

Disturbed by the growing power of Adolf Hitler, in 1940 he helped establish the Union for Democratic Action, an organisation that called for American assistance to defeat fascism. Other members included Reinhold Niebuhr, George S. Counts, Louise Bowen and Louis Fraina.

After threatening to organize a March on Washington in June, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on 25th June, 1941, barring discrimination in defence industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act).

After the Second World War Randolph led a campaign in favour of racial equality in the military. This resulted in Harry S. Truman issuing executive order 9981 on 26th July, 1948, banning segregation in the armed forces.

When the AFL merged with the CIO, Randolph became vice president of the new organisation. He also became president of the Negro American Labor Council (1960-66).

In 1963 Randolph began involved in what became known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was a great success and estimates on the size of the crowd varied from between 250,000 to 400,000. Speakers along with Randolph included Martin Luther King (SCLC), Floyd McKissick (CORE), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Witney Young (National Urban League) and Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO). King was the final speaker and made his famous I Have a Dream speech.

In his final years Randolph worked closely with Bayard Rustin in the AFL-CIO funded, Philip Randolph Institute, that was established in 1966.

Asa Philip Randolph died in New York on 16th May, 1979.

On this day in 1894 Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, the grandson of a serf and the son of a coal miner, was born in Kalinovka, Ukraine. After a brief formal education Khrushchev found work as a pipe fitter in Yuzovka.

During the First World War Khrushchev became involved in trade union activities and after the October Revolution joined the Bolsheviks.

In January, 1919, Khrushchev joined the Red Army and fought against the Whites in the Ukraine during the Civil War. After leaving the army he returned to Yuzovka where he returned to school to finish his education.

Khrushchev remained active in the Communist Party and in 1925 was employed as party secretary of the Petrovsko-Mariinsk. Lazar Kaganovich, the general-secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, was impressed with Khrushchev and invited him to accompany him to the 14th Party Congress in Moscow. With the support of Kaganovich, Khrushchev made steady progress in the party hierarchy. In 1938 Khrushchev became secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party and was employed by Joseph Stalin to carry out the Great Purge in the Ukraine. The following year he became a full member of the Politburo.

Khrushchev was aware that he had to be very careful in his dealings with Stalin: "Even though I agreed with Stalin completely, I knew I had to watch my step in answering him. One of Stalin's favourite tricks was to provoke you into making a statement - or even agreeing with a statement - which showed your true feelings about someone else. It was perfectly clear to me that Stalin and Beria were very close. To what extent this friendship was sincere, I couldn't say, but I knew it was no accident that Beria had been Stalin's choice for Yezhov's replacement."

Khrushchev also worked closely with Lavrenti Beria. "Beria and I started to see each other frequently at Stalin's. At first I liked him. We had friendly chats and even joked together quite a lot, but gradually his political complexion came clearly into focus. I was shocked by his sinister, two-faced, scheming hypocrisy."

After the invasion of Poland in 1940 Khrushchev was given the responsibility of suppressing the Polish and Ukrainian nationalists. When the German Army invaded the Soviet Union in June, 1941, Khrushchev arranged the evacuation of much of the region's industry. During the Second World War Khrushchev granted the rank lieutenant general, and was given the task of organizing guerrilla warfare in the Ukraine against the Germans.

When the German Army retreated in 1944 Khrushchev was once again placed in control of the Ukraine and the rebuilding of the region. Khrushchev job was made more difficult by the famine of 1946. This brought him into conflict with Joseph Stalin who accused Khrushchev of concentrating too much on feeding the people living of the Ukraine rather than exporting food to the rest of the Soviet Union.

Khrushchev was demoted in 1951 and replaced as the minister responsible for agriculture. On the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, Gregory Malenkov became both prime minister and head of the Communist Party. He appeared to be a reformer and called for a higher priority to be given to consumer goods. He later argued that he was not fully aware of the crimes committed by Stalin: "I still mourned Stalin as an extraordinary powerful leader. I knew that his power had been exerted arbitrarily and not always in the proper direction, but in the main Stalin's strength, I believed, had still been applied to the reinforcement of Socialism and to the consolidation of the gains of the October Revolution. Stalin may have used methods which were, from my standpoint, improper or even barbaric, but I hadn't yet begun to challenge the very basis of Stalin's claim to a special honour in history. However, questions were beginning to arise for which I had no ready answer. Like others, I was beginning to doubt whether all the arrests and convictions had been justified from the standpoint of judicial norms. But then Stalin had been Stalin. Even in death he commanded almost unassailable authority, and it still hadn't occurred to me that he had been capable of abusing his power."

In September, 1953, Khrushchev became first secretary of the Communist Party. He arranged for the execution of Lavrenti Beria, head of the Secret Police and gradually he gained control of the party machinery. In 1955 he joined with Nikolai Bulganin to oust Gregory Malenkov from power. He also decided to condemn Stalin's period of rule in the Soviet Union.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He argued: "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism."

Khrushchev condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. During the speech he suggested that Stalin had ordered the assassination of Sergy Kirov. Later Khrushchev launched an investigation into the assassination of Kirov and other Stalin crimes. However, according to one insider, Feliks Chuev, the Shvernik Commission "found nothing against Stalin" but "Khrushchev refused to publish it - it was of no use to him."

In the summer of 1956 Gregory Malenkov, Nikolai Bulganin, Vyacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich attempted to oust Khrushchev This was unsuccessful and Khrushchev now purged his opponents in the Communist Party. Mikhail Gorbachev was one of those who supported Khrushchev's actions: "Khrushchev's secret speech at the XXth Party Congress caused a political and psychological shock throughout the country. At the Party krai committee I had the opportunity to read the Central Committee information bulletin, which was practically a verbatim report of Khrushchev's words. I fully supported Khrushchev's courageous step. I did not conceal my views and defended them publicly. But I noticed that the reaction of the apparatus to the report was mixed; some people even seemed confused."

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact.

Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. Imre Nagy was imprisoned and executed in 1958.

In 1958 Khrushchev replaced Gregory Malenkov as prime minister and was now the undisputed leader of both state and party. In the Soviet Union he promoted reform of the Soviet system and began to place an emphasis on the production of consumer goods rather than on heavy industry.

Nikita Khrushchev eased censorship in the Soviet Union and allowed One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Alexander Solzhenitsyn to be published. Some pointed out that this was part of his de-Stalinization policy and did not reflect a genuine increase in freedom. His critics pointed out that books such as Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak were still banned.

In 1959 Khrushchev announced a change in foreign policy. In 1959 visited the United States and offered "the capitalist countries peaceful competition". Khrushchev was due to attend the Paris Summit Conference in 1960 when a reconnaissance plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. He cancelled the meeting and later that year at the Union Nations he attacked Western influence in the Congo.

When John F. Kennedy replaced Dwight Eisenhower as president of the United States he was told about the CIA plan to invade Cuba. Kennedy had doubts about the venture but he was afraid he would be seen as soft on communism if he refused permission for it to go ahead. Kennedy's advisers convinced him that Castro was an unpopular leader and that once the invasion started the Cuban people would support the ClA-trained forces.

On April 14, 1961, B-26 planes began bombing Cuba's airfields. After the raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs. The attack was a total failure. Two of the ships were sunk, including the ship that was carrying most of the supplies. Two of the planes that were attempting to give air-cover were also shot down. Within seventy-two hours all the invading troops had been killed, wounded or had surrendered.

At the beginning of September 1962, U-2 spy planes discovered that the Soviet Union was building surface-to-air missile (SAM) launch sites. There was also an increase in the number of Soviet ships arriving in Cuba which the United States government feared were carrying new supplies of weapons. President Kennedy complained to the Soviet Union about these developments and warned them that the United States would not accept offensive weapons (SAMs were considered to be defensive) in Cuba.

On September 27, a CIA agent in Cuba overheard Castro's personal pilot tell another man in a bar that Cuba now had nuclear weapons. U-2 spy-plane photographs also showed that unusual activity was taking place at San Cristobal. However, it was not until October 15 that photographs were taken that revealed that the Soviet Union was placing long range missiles in Cuba.

President Kennedy's first reaction to the information about the missiles in Cuba was to call a meeting to discuss what should be done. Fourteen men attended the meeting and included military leaders, experts on Latin America, representatives of the CIA, cabinet ministers and personal friends whose advice Kennedy valued. This group became known as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. Over the next few days they were to meet several times.

At the first meeting of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, the CIA and other military advisers explained the situation. After hearing what they had to say, the general feeling of the meeting was for an air-attack on the missile sites. Remembering the poor advice the CIA had provided before the Bay of Pigs invasion, John F. Kennedy decided to wait and instead called for another meeting to take place that evening. By this time several of the men were having doubts about the wisdom of a bombing raid, fearing that it would lead to a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. The committee was now so divided that a firm decision could not be made.

The Executive Committee of the National Security Council argued amongst themselves for the next two days. The CIA and the military were still in favour of a bombing raid and/or an invasion. However, the majority of the committee gradually began to favour a naval blockade of Cuba. Kennedy accepted their decision and instructed Theodore Sorensen, a member of the committee, to write a speech in which Kennedy would explain to the world why it was necessary to impose a naval blockade of Cuba.

As well as imposing a naval blockade, Kennedy also told the air-force to prepare for attacks on Cuba and the Soviet Union. The army positioned 125,000 men in Florida and was told to wait for orders to invade Cuba. If the Soviet ships carrying weapons for Cuba did not turn back or refused to be searched, a war was likely to begin. Kennedy also promised his military advisers that if one of the U-2 spy planes were fired upon he would give orders for an attack on the Cuban SAM missile sites.

The world waited anxiously. A public opinion poll in the United States revealed that three out of five people expected fighting to break out between the two sides. There were angry demonstrations outside the American Embassy in London as people protested about the possibility of nuclear war. Demonstrations also took place in other cities in Europe. However, in the United States, polls suggested that the vast majority supported Kennedy's action.

On October 24, President John F. Kennedy was informed that Soviet ships had stopped just before they reached the United States ships blockading Cuba. That evening Khrushchev sent an angry note to Kennedy accusing him of creating a crisis to help the Democratic Party win the forthcoming election.

On October 26, Khrushchev sent Kennedy another letter. In this he proposed that the Soviet Union would be willing to remove the missiles in Cuba in exchange for a promise by the United States that they would not invade Cuba. The next day a second letter from Khrushchev arrived demanding that the United States remove their nuclear bases in Turkey.

While the president and his advisers were analyzing Khrushchev's two letters, news came through that a U-2 plane had been shot down over Cuba. The leaders of the military, reminding Kennedy of the promise he had made, argued that he should now give orders for the bombing of Cuba. Kennedy refused and instead sent a letter to Khrushchev accepting the terms of his first letter.

Khrushchev agreed and gave orders for the missiles to be dismantled. Eight days later the elections for Congress took place. The Democrats increased their majority and it was estimated that Kennedy would now have an extra twelve supporters in Congress for his policies.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was the first and only nuclear confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. The event appeared to frighten both sides and it marked a change in the development of the Cold War.

The Military and the leaders of the Communist Party felt humiliated by Khrushchev climbdown over Cuba. His agricultural policy was also a failure and the country was forced to import increasing amounts of wheat from Canada and the United States.

On 14th October, 1964, the Central Committee forced Khrushchev to resign. He lived in retirement in Moscow where he wrote his memoirs, Khrushchev Remembers (1971). Nikita Khrushchev died on 11th September, 1971.

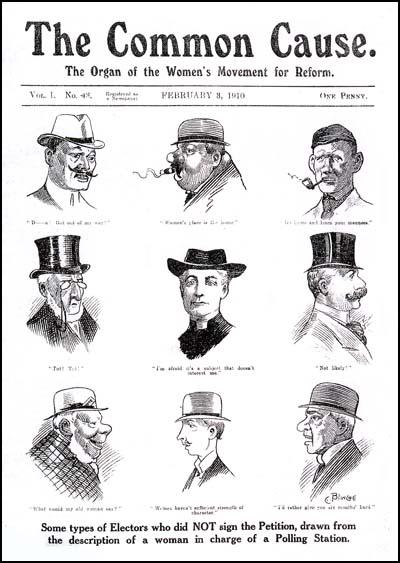

On this day in 1909 the first edition of the suffrage newspaper, Common Cause was published. Mainly financed by Margaret Ashton, it supported the policies of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and in its first edition it stated that it was "the organ of the women's movement for reform". Helena Swanwick was the newspaper's first editor, at an annual salary of £200. Clementina Black and Maude Royden also had spells as editor.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), the newspaper "enabled the local societies to keep in touch weekly with both the activities of the executive committee and with each other." It also helped to increase membership from 13,429 in 1909 to 21,571 to 1910. It now had 207 societies and its income had reached £14,000.

In 1913 the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had nearly had 100,000 members. Katherine Harley, a senior figure in the NUWSS, suggested holding a Woman's Suffrage Pilgrimage in order to show Parliament how many women wanted the vote. According to Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women (1987) argued: "A pilgrimage refused the thrill attendant on women's militancy, no matter how strongly the militancy was denounced, but it also refused the glamour of an orchestrated spectacle." Members of the NUWSS set off on 18th June, 1913.

During the next six weeks held a series of meetings all over Britain where they sold Common Cause and other NUWSS literature. The meetings held on the way were nearly all peaceful. However, the women had to endure a great deal of abuse. Harriet Blessley of Portsmouth recalled: "It is difficult to feel a holy pilgrim when one is called a brazen hussy." The campaign was a great success and b y 1914 the NUWSS had over 600 societies and an estimated 100,000 members.

Soon after the 1918 Qualification of Women Actwas passed, that gave women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities, the vote, Common Cause, ceased publication.

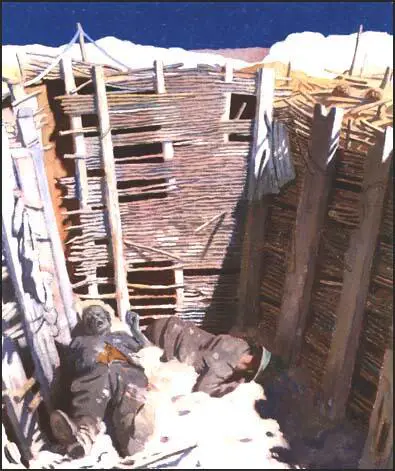

On this day in 1917 war artist William Orpen wrote a letter to his wife describing the Western Front.

"I cannot describe the impression I have formed from what I have already seen - that such a machine has been going on in over 2 years and growing bigger everyday is past comprehension, it makes one look on human beings as a different breed than one had ever imagined them before, the nobility and self sacrifice are beyond understanding. The whole thing is fine noble and bold.

Of course there is the other side, today when I had finished work, I went over some country that was really terrible, it was fought over last about 3 weeks ago, everything is left practically as it was, they have now started to bury the dead in some parts of it Germans and English mixed, this consists of throwing some mud over the bodies as they lie, they don't even worry to cover them altogether arms and feet showing in lots of cases.

The whole country is obliterated. In miles and miles nothing left at all except shell holes full of water you pick your way between them or jump at times, miles and miles of shell holes bodies rifles steel helmets gas helmets and all kinds of battered clothes, German and English, dud shells and wire, all and everything white with mud, and one feels the horrors the water in the shell holes is covering - and not a living soul anywhere near, a truly terrible peace in the new and terribly modern desert - it was a relief to get back to the road and people.

The roads behind the line are wonderful one moving mass of men, horses, mules, ammunition, guns food, fodder, pontoons and every imaginable kind of war material all struggling in one steady stream up these battered thoroughfares, all white with mud halting and struggling on again at regular intervals it is a wonderful sight full of grim determination."

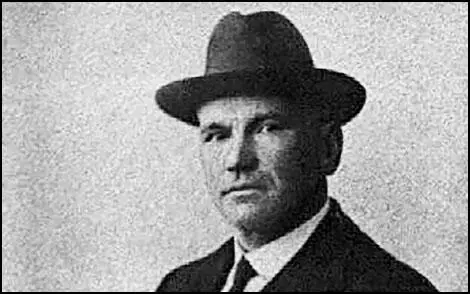

On this day in 1918 John Maclean was arrested for sedition. Maclean was totally against Britain's involvement in the First World War. He wrote an article in Justice where he argued: "It is our business as Socialists to develop a 'class patriotism,' refusing to murder one another for a sordid world capitalism. The absurdity of the present situation is surely apparent when we see British Socialists going out to murder German Socialists with the object of crushing Kaiserism and Prussian militarism. The only real enemy to Kaiserism and Prussian militarism, I assert against the world, was and is German Social-Democracy. Let the propertied class go out, old and young alike, and defend their blessed property. When they have been disposed of, we of the working class will have something to defend, and we shall do it."

In 1915 a group of Scottish socialists, including Maclean, Willie Gallacher, John Muir, David Kirkwood, and John MacLean, formed the Clyde Workers' Committee, an independent organisation of the rank and file. The CWC attempted to confront Government demands over dilution and conscription.

Maclean produced a journal called The Vanguard where he campaigned against the First World War. Maclean and James Maxton were both arrested and charged with sedition under the terms of the Defence of the Realm Act. Found guilty, the men served over a year in prison. The Govan School Board sacked Maclean from his teaching post at Lorne Street School.

Maclean was released from prison in 1916 and returned to work with the Clyde Workers' Committee. Senior members of the CWC, including Willie Gallacher, David Kirkwood and Arthur McManus helped organize production in Beardmore's Mile End Shell Factory. Kirkwood later remarked: "What a team! We organized a bonus system in which everyone benefited by high production... The factory, built for a 12,000 output, produced 24,000. In six weeks, we held the record for output in Great Britain, and we never lost our premier position." Maclean was opposed to this strategy. He wrote: "Lloyd George's purpose is to coax you to relax your Trade Union rules about non-union workers. The dangers... are the weakening of your unions and the lowering of your wages."

McManus had been impressed with the achievements of the Bolshevik Government following the Russian Revolution and in January 1918 Maclean was elected to the chair of the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets. The following month he was appointed Bolshevik consul in Scotland.

On 15th April 1918, John Maclean was arrested for sedition. He was refused bail and his trial fixed for 9th May in Edinburgh. He conducted his own defence. He argued that in his lectures he had "pointed out that as a consequence of the robbery that goes on in all civilised countries today, our respective countries have had to keep armies, and that inevitably our armies must clash together. On that and on other grounds, I consider capitalism the most infamous, bloody and evil system that mankind has ever witnessed.... I wish no harm to any human being, but I, as one man, am going to exercise my freedom of speech. No human being on the face of the earth, no government is going to take from me my right to speak, my right to protest against wrong, my right to do everything that is for the benefit of mankind. I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot."

Maclean was found guilty and sentenced to five years. While in Peterhead Prison Maclean started a hunger strike. His wife wrote to a fellow member of the Socialist Labour Party: "John has been on hunger strike since July. He resisted the forcible feeding for a good while, but submitted to the inevitable. Now he is being fed by a stomach tube twice daily. He has aged very much and has the look of a man who is going through torture... Seemingly anything is law in regard to John. I hope you will make the atrocity public. We must get him out of their clutches. It is nothing but slow murder..."

Following the armistice he was released from prison on 3rd December 1918. Maclean formed the Tramp Trust Unlimited in 1919, an organisation that campaigned for a minimum wage, a six-hour day and full wages for the unemployed.

On this day in 1921 the Triple Industrial Alliance called off their planned strike (Black Friday). After the First World War the ending of price controls, prices rose twice as fast during 1919 as they had done during the worst years of the war. That year 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike - this was six times the 1918 rate. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. There were also mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool.

The miners were encouraged to go back to work by the government agreeing to establish a royal commission under John Sankey, a high court judge. Others on the commission included trade unionists, Frank Hodges, Robert Smillie and Herbert Smith. Other progressive figures such as R. H. Tawney, Sidney Webb and Leo Chiozza Money, were also included, but Arthur Balfour, and several conservative businessmen meant that they could not publish a united report.

In June 1919 the Sankey Commission came up with four reports, which ranged from complete nationalization on the part of the workers' representatives to restoration of undiluted private ownership on that of the owners. On 18th August, Lloyd George used the excuse of this disagreement to reject nationalization but offered the prospect of reorganization. When this was rejected by the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, the government kept control of the industry. It also agreed to pass legislation that would guarantee the miners a seven-hour day.

In January 1921, Arthur J. Cook, from South Wales became a member of the executive of the MFGB. Over the next few months he became one of Hodges main critics: In February, "the decontrol of the mining industry was announced, with a consequent end to a national wages agreement and wage reductions. A three-month lock-out from April 1921 ended in defeat for the miners; at its end Cook was again gaoled for two months' hard labour for incitement and unlawful assembly".

On 14th April, 1921, Hodges spoke to a meeting of M.P.s in the House of Commons. An answer he gave in reply to questions was taken up and reported as indicating that the miners were prepared to compromise. However, the MFGB executive refused to enter fresh talks. The other members of the Triple Industrial Alliance, the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the National Transport Workers' Federation (later the Transport & General Workers Union) urged them to change their mind. When they refused, they called off their planned industrial action on Friday, 15th April. This was a great disappointment both to the miners and trade union militants, and the day has gone down in labour industry as "Black Friday".

On this day in 1922 an investigation began into the Teapot Dome Scandal. In the early part of the 20th century large oil reserves were discovered at Elk Hills, California and Teapot Dome, Wyoming. In 1912 President William Taft decided that this government owned land and its oil reserves should be set aside for the use of the United States Navy.

On 4th June, 1920, Congress passed a bill that stated that the Secretary of the Navy would have the power "to conserve, develop, use and operate the same in his discretion, directly or by contract, lease, or otherwise, and to use, store, exchange, or sell the oil and gas products thereof, and those from all royalty oil from lands in the naval reserves, for the benefit of the United States."

In March 1921 President Warren Harding appointed Albert Fall as Secretary of the Interior. Soon afterwards he persuaded Edwin Denby, the Secretary of the Navy, that he should take over responsibility for the Naval Reserves at Elk Hills and Teapot Dome. Later that year Fall decided that two of his friends, Harry F. Sinclair (Mammoth Oil Corporation) and Edward L. Doheny (Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Company), should be allowed to lease part of these Naval Reserves.

Attempts were made to keep this deal secret but rumours began to circulate when it became known that Albert Fall was spending large sums of money. On 14th April, 1922, the Wall Street Journal reported that Fall had leased Teapot Dome to Harry F. Sinclair. President Warren Harding defended Fall by claiming that "the policy which has been adopted by the Secretary of the Navy and the Secretary of the Interior in dealing with these matters was submitted to me prior to the adoption thereof, and the policy decided upon and the subsequent acts have at all times had my entire approval."

Robert La Follette and John B. Kendrick called for a Senate investigation into Albert Fall and the Naval Reserves. President Warren Harding died suddenly on 2nd August, 1923 and was replaced by his vice-president, Calvin Coolidge.

Hearings on the Teapot Dome oil lease began on October 15, 1923 before the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys. Senator Thomas J. Walsh, a Democrat from Montana, led the committee's investigation. Over the next few months, dozens of witnesses testified before the committee. On January 24, 1924, Edward Doheny admitted that he had lent Fall $100,000.

Seven days later the Senate passed a resolution stating that the leases to the Mammoth Oil Company and the Pan American Petroleum Company "were executed under circumstances indicating fraud and corruption". Albert Fall and Edwin Denby were now both forced to resign from office.

On 17th October, 1927, Harry F. Sinclair appeared on trial charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States. The trial ended prematurely two weeks later when the government presented evidence that Sinclair had hired a detective agency to shadow the jury. The judge declared a mistrial. Sinclair was tried for criminal contempt of court. Found guilty and he was sentenced to six months in prison.

Albert Fall was now charged accepting a bribe from Doheny. On October 7, 1928 the trial began in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. Even though the trial concerned Fall accepting money from Doheny, the judge allowed M. T. Everhart's testimony showing the financial relationship between Sinclair and Fall. That testimony was used to show that Fall had lied to the Senate committee when he declared that he had not accepted any money from Sinclair. Fall was found guilty and sentenced to one year in prison and a $100,000 fine.

On this day in 1944 the German authorities start a new campaign against the Maquis. After Marshal Henri-Philippe Petain signed the armistice in 1940 the Gestapo began hunting down communists and socialists. Most of them went into hiding. The obvious place to go was in the forests of the unoccupied zones. Escaped soldiers from the French Army also fled to these forests. These men and women gradually formed themselves into units based on political beliefs and geographical area. These groups became known as the Maquis (the name comes from the small scrub bushes in that part of the world which they frequently used for cover against the Germans).

In the spring of 1942, communist militants, acting independently of the leadership of the French Communist Party, organized the first Maquis units in the Limousin and the Puy-de-Dôme. Maquis groups were established in other regions of France. As the Maquis grew in strength it began to organize attacks on German forces.

In the Limousin, the Maquis were led by the Communist militant, Georges Guingouin. At this time Guingouin was not supplied with any weapons. Therefore their main method of resisting the German Army was sabotage. This included attacks on bridges, telephone lines and railway tracks.

The Maquis also provided aid and protection to refugees, immigrants, Jews, and others threatened by the Vichy and the German authorities. They also helped to get Allied airman, whose aircraft had been shot down in France, to get back to Britain.

In March 1944, the German Army began a campaign of repression throughout France. This included a policy of reprisals against civilians living in towns and villages close to the scene of attacks carried out by members of the French Resistance. As one official wrote on 15th April, 1944 that the authorities "wanted to strike fear into the population and change their opinion by showing them that the evils they were suffering were the direct consequence of the existence of the Maquis and that they had made the mistake of tolerating them."

On 5th June, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower asked the BBC sent out coded messages to the resistance asking them to carry out acts of resistance during the D-day landings in order to help Allied forces establish a beachhead on the Normandy coast.

After the war General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote: "Throughout France the Resistance had been of inestimable value in the campaign. Without their great assistance the liberation of France would have consumed a much longer time and meant greater losses to ourselves."

On this day in 1980 Jean-Paul Sartre died. Sartre was born in Paris, France, on 21st June, 1905. After studying at the Sorbonne he taught philosophy at La Havre, Paris and Berlin. An existentialist, he published his autobiographical novel, Nausea in 1938.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Sartre joined the French Army and fought during the Western Offensive. Captured by the German Army in June 1940, he remained a prisoner of war until escaping in March 1941.

Sartre returned to Paris and returned to teaching and writing. This included two plays, The Flies and No Exit. He also joined the French Resistance and became co-editor with Albert Camus, of the clandestine newspaper, Combat.

After the war Sartre became a leading figure of the left-wing in France. In 1946 he founded with Simone de Beavoir, the advant-garde monthly Modern Times. He also published an explanation of his philosophy in his book Existentialism and Humanism (1948) and Being and Nothingness (1956). Other notable works include Crime Passionnel and the trilogy Paths of Freedom. His autobiography, Words, was published in 1964.

In the late 1960s Sartre became one of the leaders of the opposition to the United States policy in Vietnam. He also supported the student rebellions in 1968.