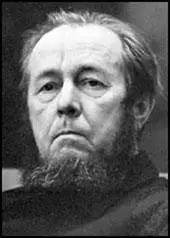

Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsky on 11th December, 1918. He attending Rostov University where he studied mathematics and took a correspondence course in literature at Moscow State University.

During the Second World War Solzhenitsyn joined the Red Army and rose to the rank of artillery captain and was decorated for bravery. While serving on the German front in 1945 he was arrested for criticizing Joseph Stalin in a letter to a friend.

Solzhenitsyn was found guilty and sent to a Soviet Labour Camp in Kazakhstan. His first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, set in a labour camp, was initially banned but after the intervention of Nikita Khrushchev, it was published in 1962.

His next novel, The First Circle (1968), described the lives of a group of scientists forced to work in a Soviet research centre, and Cancer Ward (1968), based on his experiences as a cancer patient, were both banned after Nikita Khrushchev fell from power. In 1969 Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers' Union and deported from Moscow.

In 1970 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature but was not allowed to collect it in Stockholm. Solzhenitsyn continued to write and his novel, August 1914 (1971) on the First World War, was banned in the Soviet Union but was published abroad. This was followed by his reminiscences, The Gulag Archipelago (1973). This led to his arrest and after being charged with treason, stripped of his citizenship, and was deported from the Soviet Union.

Solzhenitsyn, who collected the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1974, went to live in Vermont in the USA. He continued to write and Lenin in Zurich was published in 1975. This was followed by two works of non-fiction, The Oak and the Calf(1980) and The Mortal Danger (1983) and the novel, November 1916 (1993).

In 1994 Mikhail Gorbachev restored Solzhenitsyn's citizenship and the charge of treason was dropped. Later that year he returned to the Soviet Union where he called for a return to pre-Bolshevik autocratic government.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn died of heart failure near Moscow on 3rd August 2008, at the age of 89.

Primary Sources

(1) Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (1973)

Following an operation, I am lying in the surgical ward of a camp hospital. I cannot move. I am hot and feverish, but nonetheless my thoughts do not dissolve into delerium, and I am grateful to Dr. Boris Nikolayevich Kornfeld, who is sitting beside my cot and talking to me all evening. The light has been turned out, so it will not hurt my eyes. There is no one else in the ward.

Fervently he tells me the long story of his conversion from Judaism to Christianity. I am astonished at the conviction of the new convert, at the ardor of his words.

We know each other very slightly, and he was not the one responsible for my treatment, but there was simply no one here with whom he could share his feelings. He was a gentle and well-mannered person. I could see nothing bad in him, nor did I know anything bad about him. However, I was on guard because Kornfeld had now been living for two months inside the hospital barracks, without going outside. He had shut himself up in here, at his place of work, and avoided moving around camp at all.

This meant that he was afraid of having his throat cut. In our camp it had recently become fashionable to cut the throats of stool pigeons. This has an effect. But who could guarantee that only stoolies were getting their throats cut? One prisoner had had his throat cut in a clear case of settling a sordid grudge. Therefore the self-imprisonment of Kornfeld in the hospital did not necessarily prove that he was a stool pigeon.

It is already late. The whole hospital is asleep. Kornfeld is finishing his story:

"And on the whole, do you know, I have become convinced that there is no punishment that comes to us in this life on earth which is undeserved. Superficially it can have nothing to do with what we are guilty of in actual fact, but if you go over your life with a fine-tooth comb and ponder it deeply, you will always be able to hunt down that transgression of yours for which you have now received this blow."

I cannot see his face. Through the window come only the scattered reflections of the lights of the perimeter outside. The door from the corridor gleams in a yellow electrical glow. But there is such mystical knowledge in his voice that I shudder.

Those were the last words of Boris Kornfeld. Noiselessly he went into one of the nearby wards and there lay down to sleep. Everyone slept. There was no one with whom he could speak. I went off to sleep myself.

I was wakened in the morning by running about and tramping in the corridor; the orderlies were carrying Kornfeld's body to the operating room. He had been dealt eight blows on the skull with a plasterer's mallet while he slept. He died on the operating table, without regaining consciousness.

(2) Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (1973)

It was granted to me to carry away from my prison years on my bent back, which nearly broke beneath its load, this essential experience: how a human being becomes evil and how good. In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer and an oppressor. In my most evil moments I was convinced that I was doing good, and I was well supplied with systematic arguments. It was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the first stirrings of good. Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either, but right through every human heart, and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. Even within hearts overwhlemed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained; and even in the best of all hearts, there remains a small corner of evil.