Britain at War: 1939-1940

Maxim Litvinov, Commissar for Foreign Affairs, denounced Hitler's decision to occupy Prague. Later that day, the British Foreign Office, asked Litvinov what would be the Soviet Union's attitude be towards Hitler if he ordered the invasion of countries such as Poland and Rumania. Joseph Stalin replied when he proposed an alliance between Britain, France and the Soviet Union, where the three powers would jointly guarantee all the countries between the Baltic and the Black Sea against aggression. (1)

On 18th March, 1939, the Cabinet met to discuss Stalin's proposal to convene a conference of Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Poland, Rumania and Turkey to find a collective means of resisting further aggression. Neville Chamberlain did not like the idea. He wrote to a friend: "I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears." (2)

After the successful invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hitler began to make demands on the Polish government. This included a request for the return of the free city of Danzig and the amendment of the Polish corridor. Not surprisingly, Poland called on the British government for help. On 24th April, 1939, Colonel Józef Beck, the Polish foreign minister, arrived in London and proposed a secret understanding involving Britain, France and Poland. Chamberlain welcomed the suggestion as he wanted to pursue a policy of deterrence, without extreme provocation." (3)

John Charmley, the author of Chamberlain and the Lost Peace (1989) has argued: "All this was part of Chamberlain's policy of constructing a diplomatic barrier to German expansion in the east. The distrust felt by these countries for Russia had been one of the three reasons for not getting too closely involved with the Soviets... Then there was the problem of the Russian alliance; for all that the Cabinet, the Labour Party and the Adullamites (Churchill and other Conservative rebels) favoured it, Chamberlain saw that it might disrupt his peace front by frightening off Poland and Romania." (4)

The guarantee to Poland, which France joined, was officially announced on 31st March, 1939. David Lloyd George, immediately objected to the agreement. As he pointed out: "If war occurred tomorrow, you could not send a single battalion to Poland." (5) Chamberlain responded that he believed the guarantee would point "not towards war, which wins nothing or settles nothing, cures nothing, ends nothing" but would open the way towards "a more wholesome era, when reason will take place of force." (6)

On 13th April, further Anglo-French guarantees were offered to Rumania, Greece and Turkey. The following week the government introduced conscription for all males aged twenty and twenty-one. It also announced that spending limits on the army, navy and air force were abandoned and a ministry of supply to co-ordinate the supply of war materials was established. Hitler and Mussolini responded by signing a military alliance - the Pact of Steel - which added further to the idea of an inevitable war. (7)

The chiefs of staff supported the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance. On 16th May, Ernle Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, Minister for Coordination of Defence, strongly urged the conclusion of an Anglo-Soviet agreement. He warned that if the Soviet Union stood aside in a European war it might "secure an advantage from the exhaustion of the western powers" and that if negotiations failed, a Nazi-Soviet agreement was a strong possibility. Chamberlain rejected the advice and said he preferred to "extend our guarantees" in eastern Europe rather than sign an Anglo-Soviet alliance. (8)

A debate on the subject took place in the House of Commons on 19th May, 1939. The debate was short and was "practically confined to the leaders of Parties and to prominent ex-Ministers". Chamberlain made it clear that he had severe doubts about Stalin's proposal. David Lloyd George, the former prime minister called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. Clement Attlee had been campaigning for a military alliance with the Soviet Union since September, 1938, during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. (9) Attlee argued in the House of Commons that the government should form a "firm union between Britain, France and the USSR as the nucleus of a World Alliance against aggression". The government was "dilatory and fumbling" and was in danger of letting Stalin slip out of their grasp and into Hitler's hands." (10)

Winston Churchill, made a passionate speech where he urged Chamberlain to accept Stalin's offer: "There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge." (11)

On 24th May, 1939, the Cabinet discussed whether to open negotiations for an Anglo-Soviet alliance. The Cabinet was overwhelmingly in favour of an agreement. This included Lord Halifax who feared that if Britain did not do so the Soviet Union would sign an alliance with Nazi Germany. Chamberlain conceded that "in present circumstances, it was impossible to stand out against the conclusion of an agreement" but he stressed the "question of presentation was of the utmost importance." He therefore insisted that attempts should be made to hide any agreement under the banner of the League of Nations. (12)

In June, 1939, a public opinion poll showed that 84 per cent of the British public favoured an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. Negotiations progressed very slowly and it has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998), that "Chamberlain did not seem to care less whether an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed at all, kept placing obstructions in the way of concluding an agreement swiftly." (13) Chamberlain admitted: "I am so sceptical of the value of Russian help that I should not feel that our position was greatly worsened if we had to do without them." (14)

Russian and German Cooperation (1939)

Stalin's own interpretation of Britain's rejection of his plan for an anti-fascist alliance, was that they were involved in a plot with Germany against the Soviet Union. This belief was reinforced when Chamberlain met with Adolf Hitler at Munich and gave into his demands for the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Stalin now believed that the main objective of British foreign policy was to encourage Germany to head east rather than west. Stalin now decided to develop a new foreign policy. Stalin realized that war with Germany was inevitable. However, to have any chance of victory he needed time to build up his armed forces. The only way he could obtain time was to do a deal with Hitler. Stalin was convinced that Hitler would not be foolish enough to fight a war on two fronts. If he could persuade Hitler to sign a peace treaty with the Soviet Union, Germany was likely to invade Western Europe instead. (15)

Stalin was frustrated by the British approach and dismissed Maxim Litvinov, his Jewish Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Litvinov had been closely associated with the Soviet Union's policy of an anti-fascist alliance. Time Magazine reported that there were several possible reasons for the replacement of Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov. "Most ominous - and least likely - explanation of the change: Comrade Stalin had decided to ally himself with Führer Hitler. Obviously Comrade Litvinov, born of Jewish parents in a Polish town (then Russian), could not be expected to complete such an alliance with rabidly Aryan Nazis. More likely: the Soviet Union was going to follow an isolationist policy (almost as bad for the British and French). By turning isolationist it would let Herr Hitler know that as long as he keeps away from Russia's vast stretches he need not fear the Red Army. Russia might even supply the Nazis with needed raw materials for conquests. Comrade Stalin still hankered after an alliance with Great Britain and France and by dismissing his experienced, alliance-seeking Foreign Commissar was simply trying to scare the British and French into signing up. But the most likely explanation was that in the bluff and counter-bluff of present European diplomacy, Dictator Stalin was simply clearing the decks to be ready at a moment's notice to jump either way." (16)

Walter Krivitsky, a former NKVD agent, who had fled to America in the early months of 1939 was asked by a journalist what he thought were the reasons for Stalin's sacking of Litvinov. He replied, "Stalin has been driven to the parting of roads in his foreign policy and had to choose between the Rome-Berlin axis and the Paris-London axis... Litvinov personified the policy which brought the Soviet government into the League of Nations which raised the slogan of collective security, which raised the slogan of collective security, which claimed to seek collaboration with democratic powers. That policy has collapsed." (17)

However, despite the fact that Krivitsky knew Stalin very well, his warnings were ignored. (18) Negotiations continued between Britain and the Soviet Union. The main stumbling-block concerned the rights of the Soviets to "rescue any Baltic state from Hitler, even if it did not want to be rescued". Britain insisted that they would only cooperate with Soviet Russia if Poland were attacked and agreed to accept Soviet assistance. This deadlock could not be broken and Molotov suggested that they concentrated on military talks. However, the British representatives in the talks were instructed to "go very slowly". The negotiations finally ended in failure on 21st August. (19)

Molotov now began secret negotiations with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. He later claimed: "To seek a settlement with Russia was my very own idea which I urged on Hitler because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict. After a short ceremonial welcome the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and myself.... Stalin spoke - briefly, precisely, without many words; but what he said was clear and unambiguous and showed that he, too, wished to reach a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin used the significant phrase that although we had 'poured buckets of filth' over each other for years there was no reason why we should not make up our quarrel." (20)

On 28th August, 1939, the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed in Moscow. It was reported: "Late Sunday night - not the usual time for such announcements - the Soviet Government revealed a pact, not with Great Britain, not with France, but with Germany. Germany would give the Soviet Union seven-year 5% credits amounting to 200,000,000 marks ($80.000,000) for German machinery and armaments, would buy from the Soviet Union 180,000.000 marks' worth ($72,000,000) of wheat, timber, iron ore, petroleum in the next two years". (21) Apparently, the day after the agreement was signed, Stalin told Lavrenti Beria: "Of course, it's all a game to see who can fool whom. I know what Hitler's up to. He thinks he's outsmarted me, but actually it's I who have tricked him." (22)

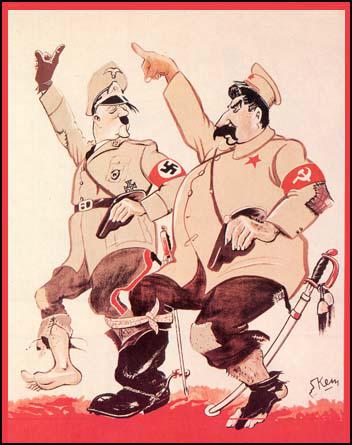

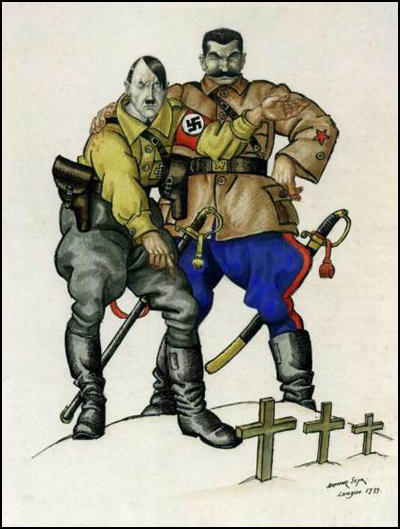

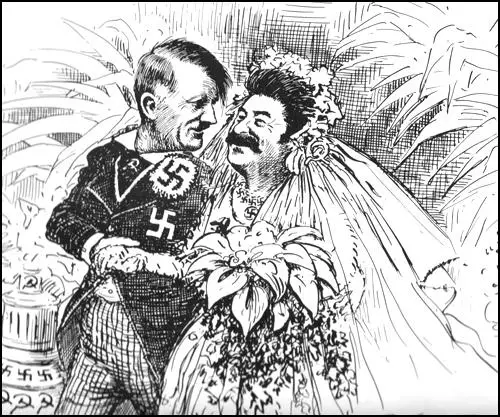

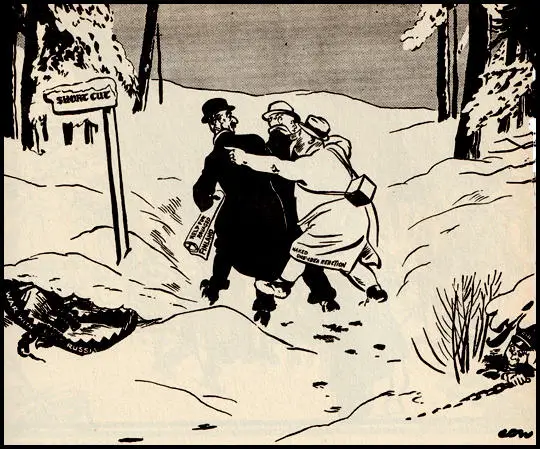

Under the terms of the agreement, both countries promised to remain neutral if either country became involved in a war. The cartoonist, David Low, who had long campaigned for an alliance with the Soviet Union, wrote: "Britain and France were dragged to war under such uninspiring and disadvantageous circumstances that it seemed hardly possible for them to win. What a situation! In gloomy wrath at missed opportunity and human stupidity I drew the bitterest cartoon of my life, Rendezvous, the meeting of the 'Enemy of the People' with the 'Scum of the Earth' in the smoking ruins of Poland." (23)

Walter Krivitsky, whose predictions had proved correct, argued in The New Leader: "Not only are the American people shocked, but far more the unhappy masses of Germany and Russia who have paid and will continue to pay for this triumph with their blood. Such master strokes are eloquent proof of the return by the totalitarian states to the darkest phases of secret diplomacy such as characterized the epoch of Absolutism... For the democratic world the importance of the pact lies in that it has finally ripped the mask from Stalin's face. I believe that in those countries where the free word still exists, the master stroke of diplomacy is the death stroke of Stalinism as an active force. I believe this because after nearly 20 years of service for the Soviet government, I am convinced that democracy; despite its present perilous position, is the sole path for progressive humanity." (24)

Lord Halifax argued that the Nazi-Soviet Pact did not make any difference as British policy had "always discounted Russia, so materially the position is not really changed." (25) On 22nd August, 1939, Chamberlain told the Cabinet, "It is unthinkable that we would not carry out our obligations to Poland." (26) Despite these comments he sent Hitler and unequivocal letter, approved by the Cabinet, which stated that Britain intended to stand by Poland. On 24th August, Chamberlain gained parliamentary agreement to pass the Emergency Powers Act. The following day, a formal Anglo-Polish military alliance was signed, to reinforce the British resolve not to abandon Poland. (27)

Herbert Morrison, the Labour MP, commented: "I believe that in 1938 and 1939 he (Chamberlain) genuinely felt that God had sent him into this world to obtain peace. That he failed may or may not be due to the inevitable ambition of Hitler to dominate the world, but there can be little doubt that in his mental attitude Chamberlain went the wrong way about it. He decided in the early stages of his discussions to treat Hitler as a normal human being and an important human being at that. At the time of the Munich crisis I said extremely critical things in public speeches about the German Chancellor with the result that I was approached by one of Chamberlain's more important ministers who asked whether I would be good enough to desist, as the prime minister had been informed that Hitler resented it." (28)

On 25th August, 1939, Hitler sent a letter to Chamberlain in which he demanded the Danzig and Polish corridor questions be settled immediately. In return for a settlement, Hitler offered a non-aggression pact to Britain and promised to guarantee the British Empire and to sign a treaty of disarmament. (29) Some appeasers such as Nevile Henderson, Richard Austen Butler and Horace Wilson, wanted to do a deal with Hitler. They were accused by Oliver Harvey of "working like beavers for a Polish Munich". (30)

The reply to Hitler went through several drafts, until it was finally agreed by the whole Cabinet on 28th August. In the letter, Chamberlain suggested direct Polish-German talks to settle the issue peacefully, but would not "acquiesce in a settlement which put in jeopardy the independence of the state to whom they had given their guarantee." (31) In response, Hitler demanded a Polish emissary "with full powers" go to Berlin on 30th August 1939, but the Polish government refused. (32)

On 31st August, 1939, Adolf Hitler gave the order to attack Poland. The following day fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility". (33)

At a meeting of the Cabinet on 2nd September, the Cabinet wanted the prime minister to declare war on Nazi Germany. Chamberlain refused and argued it was still possible to avoid conflict. That night he announced in the House of Commons that he was offering Hitler a conference to discuss the subject of Poland if the "Germans agreed to withdraw their forces (which was not the same as actually withdrawing them), the British government would forget everything that had happened, and diplomacy could start again." (34)

Clement Attlee was not in the House of Commons as he was recovering from a serious operation. It was acting leader, Arthur Greenwood, who replied to Chamberlain's statement. As he stood up, Leo Amery shouted "Speak for England, Arthur!". Greenwood said: "I am gravely disturbed. An act of aggression took place 38 hours ago. The moment that act of aggression took place one of the most important treaties of modern times automatically came into operation. There may be reasons why instant action was not taken. I am not prepared to say - and I have tried to play a straight game - I am not prepared to say what I would have done had I been one of those sitting on those Benches. That delay might have been justifiable, but there are many of us on all sides of this House who view with the gravest concern the fact that hours went by and news came in of bombing operations, and news today of an intensification of it, and I wonder how long we are prepared to vacillate at a time when Britain and all that Britain stands for, and human civilisation, are in peril. We must march with the French." (35)

Chamberlain had lost the support of his own MPs. He was shocked by this reaction and Lord Halifax commented that he had "never seen the Prime Minister so disturbed". Members of the Cabinet were also angry with Chamberlain's performance in the House of Commons. Several members of the Cabinet assembled in the office of John Simon. He later recalled: "The language and feelings of some of my colleagues were so strong and deep that I thought it right at once to inform the Prime Minister." The men drafted a letter that said "that our view was that in no circumstances should the expiry of the ultimatum go beyond 12 noon tomorrow, and even this extension of twelve hours beyond the Cabinet's earlier decision would only be acceptable if it was the necessary price of French co-operation". (36)

Edward Murrow was a critic of appeasement and heard rumours that Chamberlain was still trying to continue the negotiations with Hitler via Mussolini: "Some people have told me tonight that they believe a big deal is being cooked up which will make Munich and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia look like a pleasant tea party. I find it difficult to accept this thesis. I don't know what's in the mind of the government, but I do know that to Britishers their pledged word is important, and I should be very much surprised to see any government which betrayed that pledge remain long in office. And it would be equally surprising to see any settlement achieved through the mediation of Mussolini produce anything other than a temporary relaxation of the tension. Most observers here agree that this country is not in the mood to accept a temporary solution. And that's why I believe that Britain in the end of the day will stand where she is pledged to stand, by the side of Poland in a war that is now in progress. Failure to do so might produce results in this country, the end of which cannot be foreseen. Anyone who knows this little island will agree that things happen slowly here; most of you will agree that the British during the past few weeks have done everything possible in order to put the record straight. When historians come to sum up the last six months of Europe's existence, when they come to write the story of the origins of the war, or of the collapse of democracy, they will have many documents from which to work. As I said, I have no way of ascertaining the real reason for the delay, nor am I impatient for the outbreak of war." (37)

Shortly before midnight, on 2nd September, 1939, the Cabinet met for a second time. Members, led by Leslie Hore-Belisha, argued that the government must stop procrastinating and declare war or else he would be defeated in the House of Commons. It was agreed to issue an ultimatum which would be delivered by Nevile Henderson to the German government in Berlin at 9.00 a.m. on 3rd September 1939. It stated that unless Hitler made a firm promise to withdraw his troops from Poland by 11.00 a.m. then Britain would declare war. (38)

The following day Neville Chamberlain went on radio to announce: "Britain is at war with Germany" and went on to say: "This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established." (39)

Richard Lamb, the author of The Ghosts of Peace (1987) described it as a "pathetic broadcast" and "instead of promising speedy help to the ally on whose behalf Britain was going to war, he spoke of his personal grief." Although the people of Poland "expected immediate help, Britain had no intention of coming to Poland's aid." On 9th September, 1939, a Polish military mission led by General Norwid Neugebauer, arrived in London to have talks with William Ironside the Chief of the General Staff. However, all Ironside could offer was a few thousand old rifles and a few million rounds of ammunition, and he advised them to buy arms from neutral countries such as Spain and Belgium. (40)

The British declaration of war automatically brought in India and the colonies. The Dominions, however, were free to decide for themselves. The governments of Australia and New Zealand followed the British example at once without consulting their parliament. The Canadian government waited for their parliament and declared war on 10th September. In South Africa, J. M. B. Herzog, the prime minister, wished to remain neutral, but he lost the vote 80 to 67. Herzog resigned and Jan Smuts became prime minister and declared war on 6th September, 1939. (41)

In his diary Chamberlain attempted to explain what had happened. "The communications with Hitler and Goering looked rather promising at one time, but came to nothing in the end, as Hitler apparently got carried away by the prospect of a short war in Poland, and then a settlement... They gave the impression, probably with intention, that it was possible to persuade Hitler to accept a peaceful and reasonable solution of the Polish question, in order to get to an Anglo-German agreement, which he continually declared to be his greatest ambition... With such an extraordinary creature one can only speculate. But I believe he did seriously contemplate an agreement with us, and that he worked seriously at proposals which to his one-track mind seemed almost fabulously generous." (42)

On 17th September, the Soviet Red Army invaded Eastern Poland, the territory that fell into the Soviet "sphere of influence" according to the secret protocol of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. On 6th October, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. Joseph Stalin now demanded not only Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, as part of the Soviet sphere. He aimed both to recover the land of the Russian Empire and to secure a compact area of defence for the Soviet Union. Hitler, unwilling to fight a war on two fronts, immediately accepted these terms. (43)

On the outbreak of the Second World War Chamberlain asked Winston Churchill to join his cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill suggested that Anthony Eden and Archibald Sinclair, the Liberal Party leader, should be appointed to the War Cabinet. "Aren't we a very old team? I make out that the six you mentioned to me yesterday aggregate 386 years, or an average of over 64, only one year short of the old age Pension! If, however, you added Sinclair (49) and Eden (42), the average comes down to 57½. If the Daily Herald is right that Labour will not come in, we shall certainly have to face a constant stream of criticism, as well as the many disappointments and surprises of which war largely consists. Therefore it seems to me all the more important to have the Liberal Opposition firmly incorporated in our ranks." (44)

Eden was appointed as Secretary of State for the Dominions, but Sinclair and Clement Attlee were not invited to join Chamberlain's government. Once in office Churchill he wrote a paper where he assessed the possibility of defeating Nazi Germany. He reassured his colleagues that Germany was short "of certain vital materials, and some at least of their population was gravely disaffected... after a few months weaknesses would begin to show in the German military machine." (45)

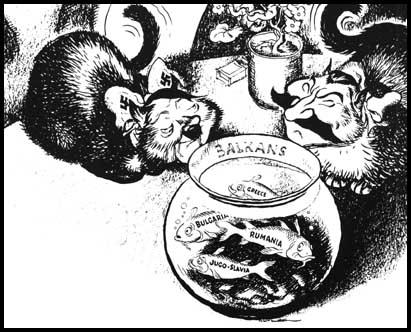

goldfish!" The Daily Mail (17th November, 1939)

In September 1939, public opinion polls showed that Chamberlain's popularity was 55 per cent. By December it had increased to 68 per cent. It would seem that some members of the general public saw him as the man who could negotiate Britain out of the war. Chamberlain reported on 23rd September: "All the injustices, inconveniences, hardships and uncertainties of wartime are resented more and more, because they are felt to be unnecessary... Last week 17% of my correspondence was on the theme of 'stop the war'. If I were in Hitler's shoes, I think I should let the present menacing lull go on for several weeks, and then put out a very reasonable offer." (46) A few weeks later he wrote: "In 3 days last week I had 2,450 letters, and 1,860 of them were 'stop the war' in one form or another." (47)

Members of the House of Commons saw him as an uninspiring war leader. Herbert Morrison, later recalled: "Neville Chamberlain was a sad and to me pathetic man. He appeared to have but little love for his fellow men. The coldness of his character encompassed him like an aura. If he had little heart he certainly had a brain. He was a first-class administrator, probably one of the most capable Ministers of Health of this century. When he became prime minister his personal tragedy was that he was genuinely aghast at the possibility of war and he adopted the role of a man of peace because he was convinced that he had the political acumen to achieve it. But he hadn't. He would not drive for collective security which could have held Hitler, and Hitler would not make a genuine peace." (48)

Conscription

After war was declared Neville Chamberlain asked Parliament to approve the Emergency Powers (Defence Act). Passed on 24th August, it empowered the government to take measures to secure public safety, the defence of the realm and the maintenance of the public order. A string of new ministries was set up - for Home Security, Economic Warfare, Food, Shipping and Information - following lessons learnt in the First World War. (49)

Over the next five days around 100 new measures were taken. This included the calling up all military reservists and Air Raid Precautions (ARP) volunteers to be mobilized. About half a million people enrolled in the ARP and others enlisted in the Territorial Army or the RAF Volunteer Reserve. Sir John Anderson was brought into the cabinet as lord privy seal and put in charge of the ARP. Expenditure on ARP went up from £9½ million a year before Munich to £51 million (including the fire services) in 1939-40. The ministry of health strove to provide some 300,000 beds. (50)

In September, 1939, the government issued a leaflet warning the public of possible air raids. "When air raids are threatened, warning will be given in towns by sirens, or hooters which will be sounded in some places by short blasts and in others by a warbling note, changing every few seconds. The warnings may be given by the police or air-raid wardens blowing short blasts on whistles. When you hear the warning take cover at once. Remember that most of the injuries in an air raid are caused not by direct hits by bombs but by flying fragments of debris or by bits of shells. Stay under cover until you hear the sirens sounding continuously for two minutes on the same note which is the signal Raiders Passed". (51)

On 27th April 1939, Neville Chamberlain made the controversial decision to introduce Conscription, although repeated pledges had been given by him against such a step. It is claimed that Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, had forced Chamberlain to change his mind. Both members of the Labour Party and the Liberal Party objected to the measure and according to Winston Churchill because of "the ancient and deep-rooted prejudice which has always existed in England against Compulsory Military Service." (52)

Clement Attlee argued: "Whilst prepared to take all necessary steps to provide for the safety of the nation and the fulfillment of its international obligations, this House regrets that His Majesty's Government in breach of their pledges should abandon the voluntary principle which has not failed to provide the man-power needed for defence, and is of opinion that the measure proposed is ill-conceived, and, so far from adding materially to the effective defence of the country, will promote division and discourage the national effort, and is further evidence that the Government's conduct of affairs throughout these critical times does not merit the confidence of the country or this House." (53)

Attlee later attempted to explain why he opposed conscription. He thought this was of doubtful military value and that military conscription might pave the way for industrial conscription. He admitted to Mark Arnold-Forster: "But you must remember the hangover from the last war. The generals were given far too many men. They sacrificed men because they wouldn't use their brains. Didn't happen in the second war." (54)

Parliament passed the Military Training Act by 380 to 143 votes. This introduced conscription for men aged 20 and 21, who were now required to undertake six months' full-time military training. Once this decision had been taken, however, the Labour Party quickly accepted it, and it soon ceased to be contentious. A resolution at the Labour Party Conference calling for non-cooperation in defence measures was defeated by a huge majority - 1,670,000 to 286,000. Attlee and the shadow cabinet continued to oppose any further concessions to Adolf Hitler. (55)

Parliament also passed legislation that protected some important occupations from national service. After consulting with business leaders, the government published the Schedule of Reserved Occupations. Employers were also able to ask for individual key workers employed in one of these occupations not to be conscripted into the armed forces. In January 1939, a handbook sent to every household in the country, which catalogued the various full-time and part-time war jobs. It was designed to check impulsive volunteering by skilled workers and to help others to find the appropriate service. Over the next few months more than 200,000 men had been granted deferment at their employers' request. By the summer of 1939 over 300,000 had volunteered for the armed forces and around 500,000 recruits for the Civil Defence services. (56)

Young men who were not wearing the uniform of the armed forces because they were working in reserved occupations, sometimes came under pressure from the local population: "Matt, my boyfriend, was exempted from call-up for a while because he was needed at home. He worked at Devonport Dockyard building ships. It got embarrassing when people in our village started to whisper: Why isn't he fighting like our men?" (57)

On the outbreak of the Second World War,the regular army and its reserves numbered about 400,000, and there was a roughly equal number of territorials. On the first day of war, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. The following May, registration had extended only as far as men aged twenty-seven. Richard Titmuss said that the "call-up" seemed "to progress with the speed of an elephant trying to compete in the Derby". (58)

To others the pace was going too fast. Frank Edwards, a 33-year-old, a businessman from Birmingham, wrote in December, 1939: "I think there were some surprised people today when the 22-year-olds were called up, owing to this being sooner than was expected, especially as it was authoritatively stated after the last call up on 21st October that it was not expected the next age group would be called on until the new year." (59)

Muriel Simkin was on honeymoon when war was declared. Soon after she arrived home her husband, John Simkin, and her brother, Jack Hughes, received their call up papers. "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life... People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that." (60)

Provision was made in the legislation for people to object to military service. Not only on pacifist grounds, which had been accepted in the First World War, but also on political grounds. Of the first batch of men aged 20 to 23, an estimated 22 in every 1,000 objected and went before local conscientious objection tribunals. The tribunals varied greatly in their attitudes towards conscientious objection to military service, and the proportions of conscientious applications totally rejected ranged from 2 per cent in London to 27 per cent in south-west Scotland. The longer the war continued, the lower the percentage objected to conscription. By the summer of 1940 only 16 in every thousand did so." (61)

Anderson Shelters

Sir John Anderson, the Home Secretary and the Minister of Home Security, commissioned the engineer, William Patterson, to design a small and cheap shelter that could be erected in people's gardens. (62) Within a few months nearly one and a half million of these Anderson Shelters were distributed to people living in areas expected to be bombed by the Luftwaffe. Anderson shelters were given free to poor people. Men who earned more than £5 a week could buy one for £7. The main problem was that under a quarter of the public had no gardens. Made from six curved sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end, and measuring 6ft 6in by 4ft 6in (1.95m by 1.35m) the shelter could accommodate six people. These shelters were half buried in the ground with earth heaped on top. The entrance was protected by a steel shield and an earthen blast wall. (63)

Man: "Yes, not even scratched."

Sidney Strube, Daily Express (November, 1940)

People who did not like going into their Anderson shelters. "We had an Anderson shelter in the garden. You were supposed to go into your Anderson shelter every night. I used to take my knitting. I used to knit all night. I was too frightened to go to sleep. You got into the habit of not sleeping. I've never slept properly since. It was just a bunk bed. I did not bother to get undressed. It was cold and damp in the shelter. I was all on my own because my husband was in the army. You would go nights and nights and nothing happened." (64)

Some people adapted their Anderson shelters to give them extra protection: "I think that a dugout is fairly safe if the people inside are a foot or two below the general surface of the ground. A bomb would have to fall right on it to make sure of killing the occupants. But so many of the Andersons I have seen in London are practically on the surface with the soil piled round them and very little on top: not enough to stop a bullet. Our Anderson is in a bank of clay and the top of it is several feet below the high ground at the back. (65)

Gas Masks

The British government believed that some form of poison gas would be used on the civilian population during the war. The government issued a warning on 3rd September, 1939, that people must go to their nearest air raid shelter during bombing attacks: "If poison gas has been used, you will be warned by means of hand rattles. If you hear hand rattles do not leave your shelter until the poison gas has been cleared away. Hand bells will tell you when there is no longer any danger from poison gas." (66)

It was therefore decided to issue a gas masks to everyone living in Britain. Over 38 million gas masks were distributed to regional centres. Gas masks contained chrysotile (white asbestos) or crocidolite (blue asbestos) in their filters. While the masks were effective in terms of being able to filter out poisonous gases like mustard gas, phosgene or chlorine gas, the filters were in fact very dangerous to humans as it was later discovered that exposure to asbestos could causes asbestosis, pleuritis, and lung cancer, as well as a number of other lethal and incurable diseases. (67)

The gas masks were produced by a company in Blackburn and after the war factory workers making the masks started showing abnormally high numbers of deaths from cancer. Tests showed that asbestos fibres can also be inhaled by wearing the masks. However, it was at late as May 2014 that the Health and Safety Executive issued a warning to schools that they should not let children touch or try on gas masks as they contained asbestos. (68)

Adult gas masks were black whereas children had 'Micky Mouse' masks with red rubber pieces and bright eye piece rims. There were also gas helmets for babies into which mothers would have to pump air with a bellows. People carried their gas masks in cardboard cases for many months. (69) Neville Chamberlain went on to radio to explain the measures the government was taking: "How horrible, fantastic, incredible, it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing." (70)

Joyce Storey lived in Bristol: "Elsie remarked that she had spoken to Mr. Fry, the local Councillor and her next-door neighbour, and he had told her in confidence that the first consignment of gas masks due to be delivered the following week would be far from adequate and it was a question of distribution. Whoever got there first would be lucky. Elsie was right about the gas masks, and several weeks later there was a mad panic for these frightful looking things at local school rooms, where they were being distributed. People reacted in the most uncivilised way because they were so certain that poison gas would be used by the Germans and there were not enough gas masks issued on that first delivery. " (71)

People were encouraged to wear gas-masks for 15 minutes a day to get used to the experience. The government threatened to punish people for not carrying gas masks. However, legislation was never passed to make it illegal. The government published posters that said: "Hitler will send no warning - so always carry your gas mask". Government advertisements appeared in newspapers pleading with people to carry their gas masks with them at all times. Teachers were instructed to send children back home to fetch their masks if they had forgotten them. Entry was occasionally refused to restaurants, or places of entertainment, to patrons who were without their survival kit. John Lewis, the department store, reminded staff that "those who come without their gas mask must not be surprised if they are dismissed as unsuitable in time of war". (72)

Gas masks were neither easy nor comfortable to wear. The gas-like odour of rubber and disinfectant made many people feel sick. One child wrote: "Although I could breathe in it. I felt as if I couldn't. It didn't seem possible that enough air was coming through the filter. The covering over my face, the cloudy Perspex in front of my eyes, and the overpowering smell of rubber, made me feel slightly panicky, though I still laughed each time I breathed out, and the edges of the mask blew a gentle raspberry against my cheeks. The moment you put it on, the window misted up, blinding you. Our mums were told to rub soap on the inside of the window, to prevent this. It made it harder to see than ever, and you got soap in your eyes. There was a rubber washer under your chin, that flipped up and hit you, every time you breathed in... The bottom of the mask soon filled up with spit, and your face got so hot and sweaty you could have screamed." (73)

H. G. Wells, the famous novelist, and Kingsley Martin, the editor of The New Statesman, both wrote articles claiming they were unwilling to carry gas masks. Philip Ziegler, the author of London at War (1995), pointed out that the authorities in London carried out a regular survey of those carrying gas-masks on Westminster Bridge in 1939: "On 6 September on Westminster Bridge 71 per cent of the men and 76 per cent of the women carried masks; by 30 October the figures were 58 and 59; by 9 November a mere 24 and 39." (74)

A study at the beginning of the war suggested that only about 75 per cent of people in London were obeying government instructions regarding gas masks. By the beginning of 1940 almost no one bothered to carry their gasmask with them. The government now announced that Air Raid Wardens would be carrying out monthly inspections of gas masks. If a person was found to have lost the gas mask they were forced to pay for its replacement. Muriel Green was in Gloucester when there was a gas leak from a building: "Very few masks were visible except soldiers and an odd child." (75)

Jessica Mitford wrote about the mood the government was creating: "All sorts of emergency measures were being taken by the Government to prepare the people for war. Thousands lined up patiently to be measured for gas-masks, only to find out that because of the haste with which the masks were manufactured the parts which were supposed to intercept gas had been inadvertendy left out. Trenches were dug in Hyde Park, causing mass discontent on the part of nannies, who complained that their little charges were always falling in. Apart from the bitter jokes caused by these inept arrangements, the atmosphere was on the whole one of dreary calm, of apathetic bowing to the inevitable." (76)

Blackouts

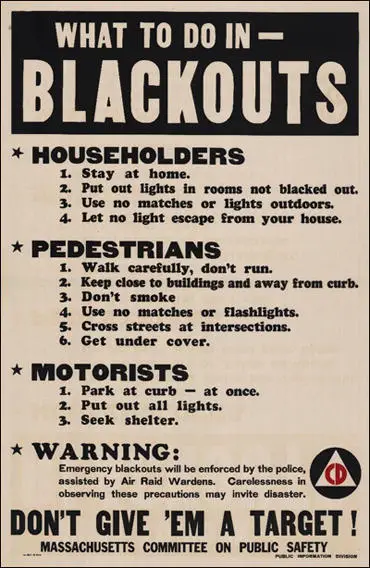

To make it difficult for the German bombers, the British government imposed a total blackout during the war. Every person had to make sure that they did not provide any lights that would give clues to the German pilots that they were passing over built-up areas. All householders had to use thick black curtains or blackout paint to stop any light showing through their windows. Shopkeepers not only had to black out their windows, but also had to provide a means for customers to leave and enter their premises without letting any light escape. (77)

Most people had to spend five minutes or more every evening blacking out their homes. "If they left a chink visible from the streets, an impertinent air raid warden or policeman would be knocking at their door, or ringing the bell with its new touch of luminous paint. There was an understandable tendency to neglect skylights and back windows. Having struggled with drawing pins and thick paper, or with heavy black curtains, citizens might contemplate going out after supper - and then reject the idea and settle down for a long read and an early night." (78)

At first, no light whatsoever was allowed on the streets. All street lights were turned off. Even the red glow from a cigarette was banned, and a man who struck a match to look for his false teeth was fined ten shillings. Later, permission was given for small torches to be used on the streets, providing the beam was masked by tissue paper and pointed downwards. There were several cases where the courts appeared to act unfairly. George Lovell put up his blackout curtain and then went outside to make sure they were effective. They were not and while he was checking he was arrested and later fined by the courts for breaking blackout regulations. One historian has argued that the blackout "transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war". (79)

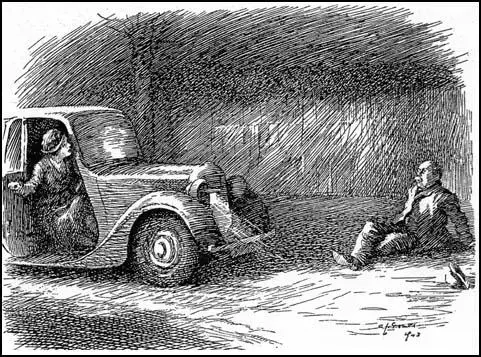

The blackout caused serious problems for people travelling by motor car. In September 1939 it was announced that the only car sidelights were allowed. The results were alarming. Car accidents increased and the number of people killed on the roads almost doubled. The king's surgeon, Wilfred Trotter, wrote an article for the British Medical Journal where he pointed out that by "frightening the nation into blackout regulations, the Luftwaffe was able to kill 600 British citizens a month without ever taking to the air, at a cost to itself of exactly nothing." (80)

Harold Nicolson wrote about the problem in his diary: "Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet." (81)

The Daily Telegraph reported in October, 1939: "Road deaths in Great Britain have more than doubled since the introduction of the black-out, it was revealed by the Ministry of Transport accident figures for September, issued yesterday. Last month 1,130 people were killed, compared with 617 in August and 554 in September last year. Of these, 633 were pedestrians." The Transport Minister Euan Wallace, "made an earnest appeal to all motor-drivers to recognise the need for a general and substantial reduction of speed in blackout conditions." (82)

Evacuation

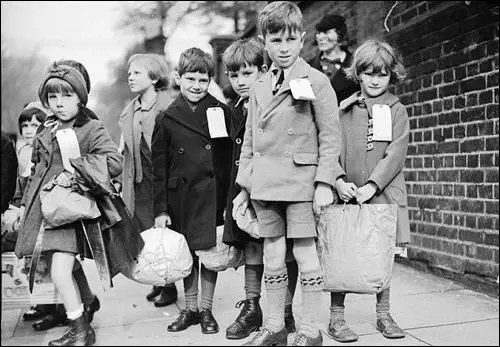

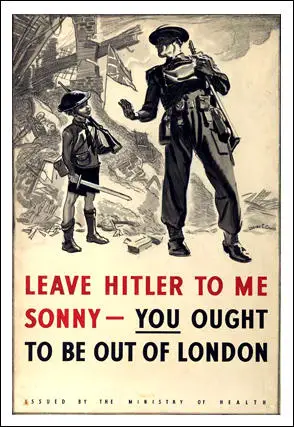

The government made plans for the evacuation of all children from Britain's large cities. Sir John Anderson, who was placed in charge of the scheme, decided to divide the country into three areas: evacuation (people living in urban districts where heavy bombing raids could be expected); neutral (areas that would neither send nor take evacuees) and reception (rural areas where evacuees would be sent). It is estimated that between June and August 1939 some 3,750,000 moved from areas thought vulnerable to those considered safe. (83)

Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, President of the Board of Education, attempted to reassure mothers anxious about their children who had been evacuated from danger zones. "I do wish that some of you parents of evacuated children could see the effects of your children of only a few days in the country. If you are feeling anxious about them, I think it would reassure you. Our task must be to save your children as far as possible from the sufferings and beastliness of modern war. So, however much you may miss them, don't take your children back just because nothing has happened during the first few days of war." (84)

In July, 1939, the government published a leaflet, Evacuation: Why and How?: "If we were involved in war, our big cities might be subjected to determined attacks from the air - at any rate in the early stages - and although our defences are strong and are rapidly growing stronger, some bombers would undoubtedly get through. We must see to it then that the enemy does not secure his chief objects - the creation of anything like panic, or the crippling dislocation of our civil life. One of the first measures we can take to prevent this is the removal of the children from the more dangerous areas. The scheme is entirely a voluntary one, but clearly the children will be much safer and happier away from the big cities where the dangers will be greatest." (85)

After the outbreak of the war the number of evacuees increased rapidly. It is believed that in September 1939 alone around a quater of the population moved. According to Angus Calder: "It was, on the surface, a triumph of calm and order. The parties, clutching gas masks and emergency rations, shepherded by their teachers, were guided and controlled by an elaborate system of banners, armlets and labels." Official records claim that 47 per cent of primary schoolchildren, and about one third of the mothers went to the designated areas. This included 827,000 schoolchildren, 524,000 mothers and children under school age going together, 13,000 expectant mothers, 7,000 blind, crippled or otherwise handicapped people; and 103,000 teachers and helpers. (86)

Jim Woods lived in Lambeth and at the age of six was evacuated with his sister. "I remember going to the station and there were literally hundreds of children lined up waiting to go. Everyone had a cardboard box with their gas masks in and a label tied to their coats to identify them if they got lost. We ended up in South Wales. The first night we slept on the floor of the church hall. The next day my sister and I were allocated to a Mr. and Mrs. Reece. At first it was quite frightening being separated from your mother and not understanding what was going on. However, after a few days we settled down and quite enjoyed being in Wales. After living in London we were now surrounded by countryside. The village was lived in was very small. There were mines close up by and we had great fun exploring the slag heaps. My sister and I got on very well with Mr. and Mrs. Reece. There were upsets sometimes. On one occasion we decided to go home to London. We followed the railway track. We thought it would take us back to London but after following it for about a mile we discovered it was a railway line used by the local mines." (87)

The billetor received received 10s. 6d. from the government for taking a child. Another 8s. 6d. per head was paid if the billetor took more than one. For mothers and infants, the billetor provided lodging only at a cost of 5s. per adult and 3s. per child. The people who took the children into their homes complained about the state of their health. Research suggests that around half of the evacuated children had fleas or headlice. Others suffered from impetigo and scabies. Muriel Green lived in the village of Snettisham in Norfolk: "The village people objected to the evacuees chiefly because of the dirtiness of their habits and clothes." (88)

Billetors were sometimes appalled by the behaviour of the evacuees. It is estimated that about 5 per cent of the evacuees lacked proper toilet training. One billetor reported about how when one six year old boy went to the toilet in the front room his mother shouted: "You dirty thing, messing up the lady's carpet. Go and do it in the corner." (89) Another report suggested: "The state of the children was such that the school had to be fumigated after the reception. Except for a small number the children were filthy, and in this district we have never seen so many verminous children lacking any knowledge of clean and hygienic habits." (90)

Oliver Lyttelton, a Member of Parliament, allowed ten children from London to live in his large country house. He later complained: "I got a shock. I had little dreamt that English children could be so completely ignorant of the simplest rules of hygiene, and that they would regard the floors and carpets as suitable places upon which to relieve themselves." (91) However, according to Richard Titmuss, evacuation meant that the "poor housed the poor... and the wealthier classes evaded their responsibilities throughout the war." (92)

The Dorking branch of the National Federation of Women's Institutes, produced a report on the children evacuated to their area. "It appeared they were unbathed for months... Condition of their boots and shoes - there was hardly a child with a whole pair and most of the children were walking on the ground - no soles, and just uppers hanging together... Many of the mothers and children were bed-wetters and were not in the habit of doing anything else... The appalling apathy of the mothers was terrible to see." (93)

Children evacuated to Oxford and Cambridge were asked to write essays explaining what they liked and disliked about their new homes. A thirteen year old girl wrote: "There isn't much that I really like in Cambridge. I like the meadows and parks in the summer but it is too cold in the winter to go there. I miss my home in Tottenham and I would rather be there than where I am. I cannot find much to do down here. I miss my sister and my friends. I haven't any of my friends living in Newnham (Cambridge) where I live and I never know where to go on Saturday and Sunday as I have no one to go with. At home I can stop in on Saturday if it is cold, but I have to take my brother out because the lady in this house goes to work and sometimes it is too cold to go anywhere. I miss my cup of tea which I always have at home after dinner. I miss my mother's cooking because the lady does not cook very well." (94)

About two million people adults privately evacuated themselves - to Wales, Devon, Scotland and other quiet areas. Constantine Fitzgibbon reported that his mother was inundated with requests to take in wealthy strangers from London: "A constant stream of private cars and London taxis" arrived in September, 1939, "filled with men and women of all ages and in various stages of hunger, exhaustion and fear, offering absurd sums for accommodation in her already overcrowded house, and even for food. This horde of satin-clad, pin-striped refugees poured through for two or three days, eating everything that was for sale, downing all the spirits in the pubs, and then vanished." (95)

Kate Eggleston, admitted that sometimes the evacuated children were badly treated: "I was at primary school when war broke out, in Nottingham. As a small child I can remember the evacuees coming. We were horrible to them. It's one of my most shameful memories, how nasty we were. We didn't want them to come, and we all ranged up on them in the playground. We were all in a big circle and the poor evacuees were herded together in the middle, and we were glaring at them and saying, 'You made us squash up in our classrooms, you've done this, you're done that.' I can remember them now, looking frightened to death. They were poor little East-Enders, they weren't tough at all, they were poor little thin, puny things. They used to be very quiet, and they only used to talk to themselves. We weren't friendly with them at all, we were very much apart, we just ignored them. It was prejudice from the teachers from the word go. When the evacuees arrived, they were pushed round from classroom to classroom in a big bunch according to their ages, in no welcoming way. All the existing children had to sit three to a bench instead of two, so we all moved up, and the evacuees sat down by the windows, which must have been the coldest and the draughtiest place in the classroom. I remember that we were put into sets, and that the 'duffers' were the ones who sat by the window, so all the evacuees were in the duffers' set." (96)

Some children were very happy with their situation: "I was 5½ years old when war was declared; I lived in Coventry with my parents and two teenage sisters... I was at school at St Joseph's Convent, which was evacuted to Stoneleigh Abbey, a fantastic country manor house with large grounds, huge trees and flowering bushes. I found it very different from life in a busy city. We slept on camp beds in the ballroom and were given navy blue blankets. I was fortunate enough to have my bed by the window and was allowed to put my teddies on the windowsill... I was delighted to find that the teacher who was sleeping with us was our music teacher... She was very kind and would comfort all the children who were homesick and explained why we had to be there. Fortunately, most of the children adapted to the situation fairly quickly." (97)

When the expected bombing of cities did not take place in 1939, parents began to doubt whether they had made the right decision in evacuating their children to safe areas. As Muriel Green pointed out: "Many evacuees returned to London because on the night of 3rd September, and the morning of the 6th there was an air-raid warning. They said they thought they had been sent to safety areas, but they decided they were no safer on the East Coast than in London especially as they have air-raid shelters in their gardens and in the parks. There are none here." (98)

By January 1940, an estimated one million evacuees had returned home. A survey carried out suggested that the lack of bombing was the reason why four out of five decided to leave. Other reasons given were homesickness among the children, dissatisfaction with the foster home and the loneliness of the parents. "Once the retreat from evacuation started, it was sure to become a rout. Parents from the same street or block of flats, travelling down to see their children at the week-ends and travelling back again together, would soon form a common resolution to bring their children back again." (99)

Neville Chamberlain Resigns

The popularity of Neville Chamberlain began to decline in the early months of 1940. It was decided to send troops to help defend Finland against the Soviet Union. This action was criticised: "The motives for the projected expedition to Finland defy rational analysis. For Great Britain and France to provoke war with Soviet Russia when already at war with Germany seems the product of a madhouse, and it is tempting to suggest a more sinister plan: switching the war on to an anti-Bolshevik course, so that the war against Germany could be forgotten or even ended." (100)

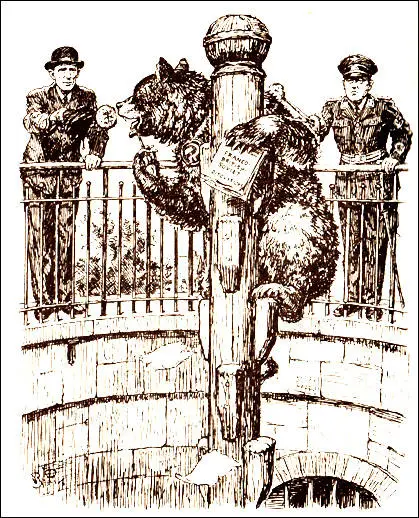

In a cartoon produced by David Low on 13th February, 1940, he attempted to illustrate Chamberlain's thinking on this issue: "When the Soviet Union attacked Finland, France, Britain and the United States sent some arms and supplies to the Finns. Blimps in the democracies, and pro-Nazi anti-Communists who saw a chance of switching enemies, wanted Chamberlain to open war on Soviet Russia, but it was too obvious that this would only play into Hitler's hands." (101)

On 12th March, 1940, Finland agreed to the Soviet demands and made peace. The British and French governments were humiliated. At a Cabinet meeting on 8th April it was agreed to send help to Norway. However, it was too late and Germany took over Denmark unopposed and seized every important Norwegian port from Oslo to Narvik. Chamberlain received a hostile reception in the House of Commons. Chamberlain complained about being "continually interrupted with shouts, sneers, and derisive laughter" and "my depression is increased by the partisanship and personal prejudice shown by the Labour Party". (102)

Harold Nicolson, a Conservative Party MP was not impressed with Chamberlain's performance: "I find that there is a grave suspicion of the Prime Minister. His speech about the Norwegian expedition has created disquiet. The House knows very well that it was a major defeat. But the P.M. said that 'the balance of advantage rested with us' and that 'Germany has not attained her objective'. They know that this is simply not true. If Chamberlain believed it himself, then he was stupid. If he did not believe it, then he was trying to deceive." (103)

In a debate in the House of Commons on 7th May, 1940, Admiral Roger Keyes, the Conservative Party MP for Portsmouth North, attacked the government's military strategy including the role played by Winston Churchill as First Lord of Admiralty: "I came to the House of Commons to-day in uniform for the first time because I wish to speak for some officers and men of the fighting, sea-going Navy who are very unhappy. I want to make it perfectly clear that it is not their fault that the German warships and transports which forced their way into Norwegian ports by treachery were not followed in and destroyed as they were at Narvik. It is not the fault of those for whom I speak that the enemy have been left in undisputable possession of vulnerable ports and aerodromes for nearly a month, have been given time to pour in reinforcements by sea and air, to land tanks, heavy artillery and mechanised transport, and have been given time to develop the air offensive which has had such a devastating effect on the morale of Whitehall. If they had been more courageously and offensively employed they might have done much to prevent these unhappy happenings and much to influence unfriendly neutrals." He then went on to compare the operation with Churchill's failure at Gallipoli. (104)

Leo Amery, another Tory MP, argued in the House of Commons: "Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peace-time statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory." Looking at Chamberlain he then went onto quote what Oliver Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go." (105)

The following day, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party demanded a vote of no confidence in Chamberlain. The 77 year-old David Lloyd George, was one of those MPs who called on the prime minister to resign. The government defeated the Labour motion by 281 to 200 votes. But the abstention of 134 Tory MPs indicated the extent to which the government had haemorrhaged authority. It was clear that drastic changes were essential if the government was to restore its authority. Chamberlain invited Attlee to join a National Government but he refused and said he would only accept if the prime minister resigned. (106)

Chamberlain told King George VI that he had no choice but to resign. In his diary he wrote: "The Amerys, Duff Coopers, and their lot are consciously, or unconsciously, swayed by a sense of frustration because they can only look on, and finally the personal dislike of Simon and Hoare had reached a pitch which I find it difficult to understand, but which undoubtedly had a great deal to do with the rebellion. A number of those who voted against the government have since either told me, or written to me to say, that they had nothing against me except that I had the wrong people in my team." (107)

The King and Chamberlain wanted Lord Halifax to become prime minister. Halifax had the support of some Labour MPs like Hugh Dalton and Herbert Morrison, but not Attlee who wanted Churchill. The King attempted to insist on Halifax but eventually he agreed to ask Winston Churchill to become prime minister. As Clive Ponting, the author of Winston Churchill (1994) pointed out: "It was perhaps the crowning irony of his career that he should become Prime Minister because of the need to bring the Labour Party, which had so far only formed two minority governments, into a national coalition. One of the main motivating forces of his political life in the previous twenty years was his outright opposition to the claims of Labour and the trade unions, reflected in his often expressed belief that not only were they unfit to govern the country but that they were engaged in a campaign to subvert its political, economic and social institutions." (108)

David Low was pleased when Winston Churchill became prime minister and responded with the cartoon, All Behind You, Winston. The cartoon showed members of his coalition government marching behind Churchill. This included Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin, Herbert Morrison, Leo Amery, Neville Chamberlain, Arthur Greenwood, Lord Halifax, Duff Cooper and Anthony Eden. Low later wrote about the background to this cartoon: "In Britain, criticism of the Government's short-comings reached a climax. Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and formed a National Government including Labour and Liberal leaders. He promised nothing but 'blood, sweat and tears'. The people were inspired with new energy and confidence." (109)

Chamberlain was appointed as Lord President of the Council in Churchill's government but ill health forced him to leave office in October 1940, and died of cancer on 9th November, 1940. His official biographer, Keith Feiling, wrote in 1946: "Though he might fail to show it in public, a man different from what he was to kith and kin and friends: simple, sensitive, and selfless, arduous, just, and merciful. For a short time, measured by the long scale of history, the standards by which he marched have been cast down and trampled on by brute force. But they will be raised again." (110)

References

(1) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949) page 422

(2) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Ida Chamberlain (26th March, 1939)

(3) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 80

(4) John Charmley, Chamberlain and the Lost Peace (1989) page188

(5) David Lloyd George, speech in the House of Commons (3rd April, 1939)

(6) The Times (19th March, 1939)

(7) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 80

(8) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 228

(9) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 226

(10) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (19th May, 1939)

(11) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (19th May, 1939)

(12) Cabinet minutes (24th May, 1939)

(13) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 84

(14) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 236

(15) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) pages 426-427

(16) Time Magazine (15th May, 1939)

(17) Walter Krivitsky, Baltimore Sun (5th May, 1939)

(18) Gary Kern, A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004) page 196

(19) A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) page 546

(20) Joachim von Ribbentrop Memoirs (1953) page 109

(21) Time Magazine (28th August, 1939)

(22) Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev Remembers (1971) page 111

(23) David Low, Autobiography (1956) page 320

(24) Walter Krivitsky, The New Leader (26th August, 1939)

(25) Andrew Roberts, The Holy Fox: A Biography of Lord Halifax (1991) page 167

(26) Cabinet minutes (22nd August, 1939)

(27) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 86

(28) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960) pages 170-171

(29) Adolf Hitler, letter to Neville Chamberlain (25th August, 1939)

(30) John Charmley, Chamberlain and the Lost Peace (1989) page 202

(31) Neville Chamberlain, letter to Adolf Hitler (28th August, 1939)

(32) Adolf Hitler, letter to Neville Chamberlain (30th August, 1939)

(33) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (1st September, 1939)

(34) Neville Chamberlain, speech in the House of Commons (2nd September, 1939)

(35) Arthur Greenwood, speech in the House of Commons (2nd September, 1939)

(36) Robert A. Parker, Chamberlain and Appeasement (1993) page 341

(37) Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London (2nd September 1939)

(38) Cabinet minutes (2nd September, 1939)

(39) Neville Chamberlain, speech on BBC radio (3rd September, 1939)

(40) Richard Lamb, The Ghosts of Peace (1987) page 122

(41) A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) page 553

(42) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (10th September, 1939)

(43) Robert Service, Stalin (2004) page 402

(44) Winston Churchill, letter to Neville Chamberlain (2nd September, 1939)

(45) Winston Churchill, memorandum to Cabinet (19th September, 1939)

(46) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (23rd September, 1939)

(47) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (8th October, 1939)

(48) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960) page 171

(49) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) pages 33-34

(50) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) page 531

(51) British government circular, Air Raid Warnings (3rd September, 1939)

(52) Winston Churchill, Gathering Storm (1948) page 276

(53) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (27th April, 1939)

(54) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 149

(55) Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left in the 1930's (1977) page 183

(56) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) pages 33-34

(57) Irene Harris, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987) page 7

(58) Richard Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy (1950) page 102

(59) Frank Edwards, Mass Observation Archive (1st December, 1939)

(60) Muriel Simkin, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987) pages 5-6

(61) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) page 52

(62) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) page 556

(63) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) pages 179-180

(64) Muriel Simkin, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987) page 6

(65) Herbert Bush, Mass Observation Archive (5th October, 1942)

(66) The Daily Telegraph (3rd September, 1939)

(67) Jay Hemmings, The British Civilian Gas Mask: Full of Chemicals As Dangerous As The Gas it Was Protecting You From (20th January, 2019)

(68) BBC news report (13th May, 2014)

(69) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) page 555

(70) Neville Chamberlain, speech on the radio (27th September, 1939)

(71) Joyce Storey, Joyce's War (1992) page 5

(72) Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004) pages 66-67

(73) Stuart Hylton, The Darkest Hour: The Hidden History of the Home Front (2001) page 93

(74) Philip Ziegler, London at War (1995) pages 73-74

(75) Muriel Green, Mass Observation Archive (11th April, 1942)

(76) Jessica Mitford, Hons and Rebels (1960) page 174

(77) British government circular Lighting Restrictions (July, 1939)

(78) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) page 63

(79) T. H. O'Brien, History of the Second World War: Civil Defence (1955) page 319

(80) Wilfed Trotter, British Medical Journal (October, 1939)

(81) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (1st September, 1939)

(82) The Daily Telegraph (19th October, 1939)

(83) Douglas Reed, A Prophet at Home (1943) page 187

(84) Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, President of the Board of Education, radio broadcast (14th September, 1939)

(85) Government leaflet, Evacuation: Why and How? (July, 1939)

(86) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) page 38

(87) Jim Woods, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987) page 14

(88) Muriel Green, Mass Observation Archive (29th November, 1939)

(89) Richard Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy (1950) page 122

(90) National Federation of Women's Institutes, Town Children Through Country Eyes (1940)

(91) Oliver Lyttelton, Memoirs of Lord Chandos (1963) page 205

(92) Richard Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy (1950) page 393

(93) National Federation of Women's Institutes, Town Children Through Country Eyes (1940)

(94) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) page 46

(95) Constantine Fitzgibbon, The Blitz (1957) page 26

(96) Kate Eggleston, quoted by Jonathan Croall, in his book, Don't You Know There's a War On? (1989) page 114

(97) Sheila A. Renshaw, Voices of the Second World War: A Child's Perspective (2017) page 21

(98) Muriel Green, Mass Observation Archive (29th November, 1939)

(99) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969) pages 46-47

(100) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) pages 572-573

(101) David Low, Years of Wrath (1949) page 101

(102) Keith Feiling, The Life of Neville Chamberlain (1970) page 430

(103) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (4th May, 1940)

(104) Roger Keyes, speech in the House of Commons (7th May, 1940)

(105) Leo Amery, speech in the House of Commons (7th May, 1940)

(106) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 240

(107) Neville Chamberlain, diary entry (11th May, 1940)

(108) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 431

(109) David Low, Years of Wrath (1949) page 109

(110) Keith Feiling, The Life of Neville Chamberlain (1970) page 458

John Simkin