Gas Masks

The British government believed that some form of poison gas would be used on the civilian population during the war. The government issued a warning on 3rd September, 1939, that people must go to their nearest air raid shelter during bombing attacks: "If poison gas has been used, you will be warned by means of hand rattles. If you hear hand rattles do not leave your shelter until the poison gas has been cleared away. Hand bells will tell you when there is no longer any danger from poison gas." (1)

It was therefore decided to issue a gas masks to everyone living in Britain. Over 38 million gas masks were distributed to regional centres. Gas masks contained chrysotile (white asbestos) or crocidolite (blue asbestos) in their filters. While the masks were effective in terms of being able to filter out poisonous gases like mustard gas, phosgene or chlorine gas, the filters were in fact very dangerous to humans as it was later discovered that exposure to asbestos could causes asbestosis, pleuritis, and lung cancer, as well as a number of other lethal and incurable diseases. (2)

The gas masks were produced by a company in Blackburn and after the war factory workers making the masks started showing abnormally high numbers of deaths from cancer. Tests showed that asbestos fibres can also be inhaled by wearing the masks. However, it was at late as May 2014 that the Health and Safety Executive issued a warning to schools that they should not let children touch or try on gas masks as they contained asbestos. (3)

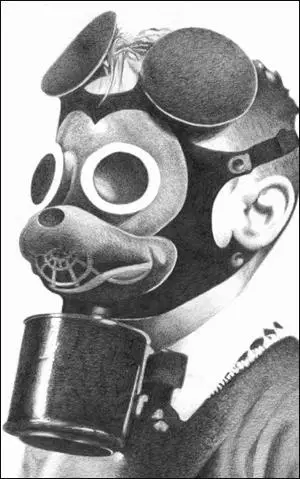

Adult gas masks were black whereas children had 'Micky Mouse' masks with red rubber pieces and bright eye piece rims. There were also gas helmets for babies into which mothers would have to pump air with a bellows. People carried their gas masks in cardboard cases for many months. (4) Neville Chamberlain went on to radio to explain the measures the government was taking: "How horrible, fantastic, incredible, it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing." (5)

Joyce Storey lived in Bristol: "Elsie remarked that she had spoken to Mr. Fry, the local Councillor and her next-door neighbour, and he had told her in confidence that the first consignment of gas masks due to be delivered the following week would be far from adequate and it was a question of distribution. Whoever got there first would be lucky. Elsie was right about the gas masks, and several weeks later there was a mad panic for these frightful looking things at local school rooms, where they were being distributed. People reacted in the most uncivilised way because they were so certain that poison gas would be used by the Germans and there were not enough gas masks issued on that first delivery. " (6)

People were encouraged to wear gas-masks for 15 minutes a day to get used to the experience. The government threatened to punish people for not carrying gas masks. However, legislation was never passed to make it illegal. The government published posters that said: "Hitler will send no warning - so always carry your gas mask". Government advertisements appeared in newspapers pleading with people to carry their gas masks with them at all times. Teachers were instructed to send children back home to fetch their masks if they had forgotten them. Entry was occasionally refused to restaurants, or places of entertainment, to patrons who were without their survival kit. John Lewis, the department store, reminded staff that "those who come without their gas mask must not be surprised if they are dismissed as unsuitable in time of war". (7)

Gas masks were neither easy nor comfortable to wear. The gas-like odour of rubber and disinfectant made many people feel sick. One child wrote: "Although I could breathe in it. I felt as if I couldn't. It didn't seem possible that enough air was coming through the filter. The covering over my face, the cloudy Perspex in front of my eyes, and the overpowering smell of rubber, made me feel slightly panicky, though I still laughed each time I breathed out, and the edges of the mask blew a gentle raspberry against my cheeks. The moment you put it on, the window misted up, blinding you. Our mums were told to rub soap on the inside of the window, to prevent this. It made it harder to see than ever, and you got soap in your eyes. There was a rubber washer under your chin, that flipped up and hit you, every time you breathed in... The bottom of the mask soon filled up with spit, and your face got so hot and sweaty you could have screamed." (8)

H. G. Wells, the famous novelist, and Kingsley Martin, the editor of The New Statesman, both wrote articles claiming they were unwilling to carry gas masks. Philip Ziegler, the author of London at War (1995), pointed out that the authorities in London carried out a regular survey of those carrying gas-masks on Westminster Bridge in 1939: "On 6 September on Westminster Bridge 71 per cent of the men and 76 per cent of the women carried masks; by 30 October the figures were 58 and 59; by 9 November a mere 24 and 39." (9)

A study at the beginning of the war suggested that only about 75 per cent of people in London were obeying government instructions regarding gas masks. By the beginning of 1940 almost no one bothered to carry their gasmask with them. The government now announced that Air Raid Wardens would be carrying out monthly inspections of gas masks. If a person was found to have lost the gas mask they were forced to pay for its replacement. Muriel Green was in Gloucester when there was a gas leak from a building: "Very few masks were visible except soldiers and an odd child." (10)

Jessica Mitford wrote about the mood the government was creating: "All sorts of emergency measures were being taken by the Government to prepare the people for war. Thousands lined up patiently to be measured for gas-masks, only to find out that because of the haste with which the masks were manufactured the parts which were supposed to intercept gas had been inadvertendy left out. Trenches were dug in Hyde Park, causing mass discontent on the part of nannies, who complained that their little charges were always falling in. Apart from the bitter jokes caused by these inept arrangements, the atmosphere was on the whole one of dreary calm, of apathetic bowing to the inevitable." (11)

Germany did not use chemical weapons during the war but a few year later the authorities began to have worries about the British gas masks that were produced by Baxters of Blackburn. Local GPs noticed factory workers that had been employed in making the masks were showing abnormally high numbers of deaths from cancer. It was pointed out that gas masks contained chrysotile (white asbestos) or crocidolite (blue asbestos) in their filters. One report suggested that working in gas mask factories resulted in the death of 10% of the workforce due to pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma. This rate was three times the normal incidence of lung or respiratory cancers." (12)

As Jay Hemmings pointed out: "Sometimes the hastily-developed technology turns out to be immensely effective, but other times it can backfire, putting the user in as much or more peril as the danger from which it is supposed to be protecting them. One such example of a supposed advance that actually turned out to be dangerous to the user was the British civilian gas mask of the Second World War.... While the masks were effective in terms of being able to filter out poisonous gases like mustard gas, phosgene or chlorine gas, the filters in them contained a chemical that we now know is extremely harmful to humans: asbestos... Asbestos, which was widely used as a heat-resistant insulator... before it was discovered just how harmful prolonged exposure was. It causes asbestosis, pleuritis, and lung cancer, as well as a number of other lethal and incurable diseases." (13)

In 1965, scientists finally confirmed the link between asbestos inhalation and cancer, now referred to as mesothelioma. It was well-documented as a Type 1 carcinogen, but many employers continued to expose their workers to asbestos through the 1970s. "Though asbestos was officially banned outright from the UK in 1999, many employees today still fail to provide safe working environments with asbestos materials still present. In fact, between 2002 and 2010, 128 British school teachers died from mesothelioma. Seventy-five percent of schools in the UK contain asbestos, and due to recent education budget cuts, it’s likely that buildings in need of proper asbestos maintenance are lacking." (14)

However, the government decided not to tell the British public about the possible dangers of wearing gas-masks during the war, fearing no doubt a large number of compensation claims. It was a story that appeared in The Lancashire Telegraph in August 2013, that suggested that gas masks posed a serious health danger. Doris Timbrell died of oesophageal cancer in November 2008. Her daughter, Patricia Nicholas, claimed that this was connected to her working at Baxters of Blackburn between 1941 and 1943 assembling gas masks and fitting filters. A compensation claim was launched against the Ministry of Defence and eventually she won nearly £48,000 in damages. (15)

The following year the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) says it analysed a number of vintage gas masks at the request of the Department for Education (DfE). According to the BBC schools were now being warned about the use of gas masks in the classroom: "The analysis showed that the majority of the masks did contain asbestos, often the more dangerous crocidolite, or blue asbestos.... Schools with these items in their collections are advised to remove them from use, double-bag them and send them for licensed disposal or to be made safe by a licensed contractor or arrange to have them displayed in a sealed cabinet." (16)

Primary Sources

(1) Jessica Mitford, Hons and Rebels (1960)

All sorts of emergency measures were being taken by the Government to prepare the people for war. Thousands lined up patiently to be measured for gas-masks, only to find out that because of the haste with which the masks were manufactured the parts which were supposed to intercept gas had been inadvertendy left out. Trenches were dug in Hyde Park, causing mass discontent on the part of nannies, who complained that their little charges were always falling in. Apart from the bitter jokes caused by these inept arrangements, the atmosphere was on the whole one of dreary calm, of apathetic bowing to the inevitable.

(2) Government leaflet published just after the outbreak of the Second World War.

If poison gas has been used you will be warned by means of hand rattles. Keep off the streets until the poison gas has been cleared away. Hand bells will be rung when there is no longer any danger. If you hear the rattle when you are out, put on your gas mask at once and get indoors as soon as you can.

(3) Joyce Storey, Joyce's War (1992)

Elsie remarked that she had spoken to Mr. Fry, the local Councillor and her next-door neighbour, and he had told her in confidence that the first consignment of gas masks due to be delivered the following week would be far from adequate and it was a question of distribution. Whoever got there first would be lucky.

Elsie was right about the gas masks, and several weeks later there was a mad panic for these frightful looking things at local school rooms, where they were being distributed. People reacted in the most uncivilised way because they were so certain that poison gas would be used by the Germans and there were not enough gas masks issued on that first delivery. We carried them everywhere with us. In fact, it became a kind of ritual to say each time we ventured forth, 'Don't forget, Gas Mask, Identity Card and Torch.'

The Identity Cards had to be carried in wallets and handbags at all times. My identity number was TKBR/82/10. There was a brisk trade done with identity bracelets and necklaces. We bought special ones for loved ones and friends. Shelters were erected in back gardens. Ours took up all the small dirt square, with the opening coming right up to the edge of the path. Each street had an Air Raid Warden. My father was the warden for our street. He had no flowers to look at now, but spent hours looking up into the sky.

(4) Winston Churchill, letter to the Secretary of State for War (15th April, 1941)

I remain far from satisfied with the state of our preparations for offensive chemical warfare, should this be forced upon us by the actions of the enemy.

I have before me a report on this matter by the Inter-Service Committee on Chemical Warfare, together with a commentary thereon by the Ministry of Supply. From these two documents the following special points emerge:

(1) The deficiency of gas shell is still serious. Although the production of 6-inch and 5.5-inch gas shell was due to start in February, none has yet been produced. I understand that the shortage of 25-pounder gas-filled shell is due to the lack of empty shell cases.

(2) The production of 30-lb. L.C. bomb, Mark I, will not keep pace with the production of the 5-inch U.P. weapon, the new mobile projector for use with the Army. Indeed, supplies will be insufficient even for training purposes.

(3) The production of phosgene gas is inadequate. The output from the plant is now about 65 per cent of capacity, having previously been only 50 per cent over a period of some months. I propose to examine the whole position at an early meeting of the Defence Committee (Supply).

In order that this examination may be as complete as possible, I shall be glad to receive from the Minister of Aircraft Production and the Minister of Supply, for circulation in advance of the meeting, brief comprehensive statements of the position so far as each is concerned, showing in respect of each of the main gas weapons and components (including gases):

(1) Total requirements notified to them, with dates.

(2) Stocks of components in the custody of each on April 1st.

(3) Supplies delivered by April to R.A.F. or Army authorities.

(4) Estimated output during each of the next six months.

I shall be glad if these statements can be submitted within a week. They should be addressed to Sir Edward Bridges.

(5) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969)

Failure to carry gas masks was never a punishable offence though in many cases factory and office workers were compelled to bring them to work by the management, and sudden mock attacks were staged in crowded streets from time to time. Even in the first week of war, no more than three-quarters of Londoners seen in the streets were carrying gas masks. By November it was a minority habit, weaker among men than among women, some of whom had replaced the official containers with nattier ones sold by the department stores. By the following spring almost no one bothered. Meanwhile, the Government had instituted a monthly inspection of masks by the air raid wardens; the citizen would be charged for the replacement or repair of a mask which he had allowed to deteriorate, or had mislaid. (The lost property offices of the railways were stacked high with unclaimed containers.)