The Struggle for Women's Rights: 1500-1870

It was not until the 16th century that women began to advocate the right of women to become involved in politics. In 1526 Elizabeth Barton, a nun, began making public speeches. According to Barton's biographer, Edward Thwaites, a crowd of about 3,000 people attended one of the meetings where she told of her visions. (1)

Bishop Thomas Cranmer was one of those who saw Barton. He wrote a letter to Hugh Jenkyns explaining that he had seen "a great miracle" that had been created by God: "Her trance lasted... the space of three hours and more... Her face was wonderfully disfigured, her tongue hanging out... her eyes were... in a manner plucked out and laid upon her cheeks... a voice was heard... speaking within her belly, as it had been in a cask... her lips not greatly moving.... When her belly spoke about the joys of heaven... it was in a voice... so sweetly and so heavenly that every man was ravished with the hearing thereof... When she spoke of hell... it put the hearers in great fear." (2)

Diane Watt has pointed out: "In the course of this period of sickness and delirium she began to demonstrate supernatural abilities, predicting the death of a child being nursed in a neighbouring bed. In the following weeks and months the condition from which she suffered, which may have been a form of epilepsy, manifested itself in seizures (both her body and her face became contorted), alternating with periods of paralysis. During her death-like trances she made various pronouncements on matters of religion, such as the seven deadly sins, the ten commandments, and the nature of heaven, hell, and purgatory. She spoke about the importance of the mass, pilgrimage, confession to priests, and prayer to the Virgin and the saints." (3)

Gradually she began to experience revelations of a controversial character. Elizabeth, now known as the Nun of Kent, was taken to see Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher. On 1st October 1528, Warham wrote to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey recommending her as "a very well-disposed and virtuous woman". He told of how "she had revelations and special knowledge from God in certain things concerning my Lord Cardinal (Wolsey) and also the King's Highness". (4)

Archbishop Warham arranged a meeting between Elizabeth Barton to see Cardinal Wolsey. She told him that she had seen a vision of him with three swords - one representing his power as Legate (the representative of the Pope), the second his power as Lord Chancellor, and the third his power to grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. (5)

Wolsey arranged for Elizabeth Barton to see the King. She told him to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain loyal to the Pope. Elizabeth then warned the King that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions". (6) William Tyndale was less convinced by her trances and claimed that her visions were either feigned or the work of the devil. (7)

In October 1532 Henry VIII agreed to meet Elizabeth Barton again. According to the official record of this meeting: "She (Elizabeth Barton) had knowledge by revelation from God that God was highly displeased with our said Sovereign Lord (Henry VIII)... and in case he desisted not from his proceedings in the said divorce and separation but pursued the same and married again, that then within one month after such marriage he should no longer be king of this realm, and in the reputation of Almighty God should not be king one day nor one hour, and that he should die a villain's death." (8)

In the summer of 1533 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer wrote to the prioress of St Sepulchre's Nunnery asking her to bring Elizabeth Barton to his manor at Otford. On 11th August she was questioned, but was released without charge. Thomas Cromwell then questioned her and, towards the end of September, Edward Bocking was arrested and his premises were searched. Bocking was accused of writing a book about Barton's predictions and having 500 copies published. (9) Father Hugh Rich was also taken into custody. In early November, following a full scale investigation, Barton was imprisoned in the Tower of London. (10)

Elizabeth Barton was examined by Thomas Cromwell, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer. During this period she had one final vision "in which God willed her, by his heavenly messenger, that she should say that she never had revelation of God". In December 1533, Cranmer reported "she confessed all, and uttered the very truth, which is this: that she never had visions in all her life, but all that ever she said was feigned of her own imagination, only to satisfy the minds of them the which resorted unto her, and to obtain worldly praise." (11)

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested that Barton had been tortured: "It may be that she was put on the rack. In any case it was declared that she had confessed that all her visions and revelations had been impostures... It was then determined that the nun should be taken throughout the kingdom, and that she should in various places confess her fraudulence." (12) Barton secretly sent messages to her adherents that she had retracted only at the command of God, but when she was made to recant publicly, her supporters quickly began to lose faith in her. (13)

Eustace Chapuys, reported to King Charles V on 12th November, 1533, on the trial of Elizabeth Barton: "The king has assembled the principal judges and many prelates and nobles, who have been employed three days, from morning to night, to consult on the crimes and superstitions of the nun and her adherents; and at the end of this long consultation, which the world imagines is for a more important matter, the chancellor, at a public audience, where were people from almost all the counties of this kingdom, made an oration how that all the people of this kingdom were greatly obliged to God, who by His divine goodness had brought to light the damnable abuses and great wickedness of the said nun and of her accomplices, whom for the most part he would not name, who had wickedly conspired against God and religion, and indirectly against the king." (14)

A temporary platform and public seating was erected at St. Paul's Cross and on 23rd November, 1533, Elizabeth Barton made a full confession in front of a crowd of over 2,000 people. "I, Dame Elizabeth Barton, do confess that I, most miserable and wretched person, have been the original of all this mischief, and by my falsehood have grievously deceived all these persons here and many more, whereby I have most grievously offended Almighty God and my most noble sovereign, the King's Grace. Wherefore I humbly, and with heart most sorrowful, desire you to pray to Almighty God for my miserable sins and, ye that may do me good, to make supplication to my most noble sovereign for me for his gracious mercy and pardon." (15)

Over the next few weeks Elizabeth Barton repeated the confession in all the major towns in England. It was reported that Henry VIII did this because he feared that Barton's visions had the potential to cause the public to rebel against his rule: "She... will be taken through all the towns in the kingdom to make a similar representation, in order to efface the general impression of the nun's sanctity, because this people is peculiarly credulous and is easily moved to insurrection by prophecies, and in its present disposition is glad to hear any to the king's disadvantage." (16)

Execution of Elizabeth Barton

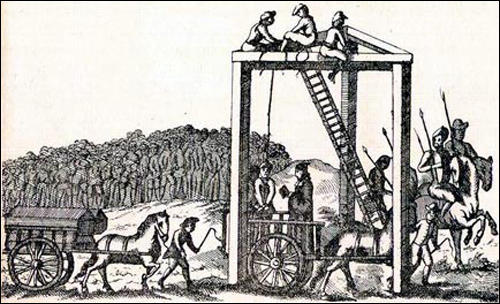

Parliament opened on 15th January 1534. A bill of attainder charging Elizabeth Barton, Edward Bocking, Henry Risby (warden of Greyfriars, Canterbury), Hugh Rich (warden of Richmond Priory), Henry Gold (parson of St Mary Aldermary) and two laymen, Edward Thwaites and Thomas Gold, with high treason, was introduced into the House of Lords on 21st February. It was passed and then passed by the House of Commons on 17th March. (29) They were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed on 20th April, 1534. They were "dragged through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn". (17)

On the scaffold she told the assembled crowd: "I have not only been the cause of my own death, which most justly I have deserved, but also I am the cause of the death of all these persons which at this time here suffer. And yet, to say the truth, I am not so much to be blamed considering it was well known unto these learned men that I was a poor wench without learning - and therefore they might have easily perceived that the things that were done by me could not proceed in no such sort, but their capacities and learning could right well judge from whence they proceeded... But because the things which I feigned was profitable unto them, therefore they much praised me... and that it was the Holy Ghost and not I that did them. And then I, being puffed up with their praises, feel into a certain pride and foolish fantasy with myself." (18)

John Husee witnessed their deaths: "This day the Nun of Kent, with two Friars Observants, two monks, and one secular priest, were drawn from the Tower to Tyburn, and there hanged and headed. God, if it be his pleasure, have mercy on their souls. Also this day the most part of this City are sworn to the King and his legitimate issue by the Queen's Grace now had and hereafter to come, and so shall all the realm over be sworn in like manner." (19) The executions were clearly intended as a warning to those who opposed the king's policies and reforms. Elizabeth Barton's head was impaled on London Bridge, while the heads of her associates were placed on the gates of the city. (20)

Sharon L. Jansen, the author of Dangerous Talk and Strange Behaviour: Women and Popular Resistance to the Reforms of Henry VIII (1996) has pointed out that historians have either "defended her as a saint or condemned her as a charlatan." (21) Jack Scarisbrick argues that most historians have dismissed her as a "mere hysteric or fraud". However, "whatever else she may or may not have been, she was indisputably a powerful, courageous and dangerous woman whom the wracking anxiety of the late summer and autumn of 1533 required should be destroyed." (22)

Anne Askew

Anne Askew was another woman who became involved in politics during the Tudor period. Askew was a supporter of Martin Luther, while her husband was a Catholic. From her reading of the Bible she believed that she had the right to divorce her husband. For example, she quoted St Paul: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? Askew was well connected. One of her brothers, Edward Askew, was cup-bearer to the king, and her half-brother Christopher, was gentleman of the privy chamber. (23)

Alison Plowden has argued that "Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them." (24)

In 1544 Askew decided to travel to London to meet Henry VIII and request a divorce from her husband. This was denied and documents show that a spy was assigned to keep a close watch on her behaviour. (25) She made contact with Joan Bocher, a leading figure in the Anabaptists. One spy who had lodgings opposite her own reported that "at midnight she beginneth to pray, and ceaseth not in many hours after." (26) Another contact was John Lascelles, who had previously worked for Thomas Cromwell, and was involved in the downfall of Catherine Howard. (27)

Rumours circulated that Askew was a close associate of Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII. As David Loades, the author of has pointed out, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007): "The Queen meanwhile continued to discuss theology, piety and the right use the bible, both with her friends and also with her husband. This was a practice, which she had established in the early days of their marriage, and Henry had always allowed her a great deal of latitude, tolerating from her, it was said, opinions which no one else dared to utter. In taking advantage of this indulgence to urge further measures of reform, she presented her enemies with an opening." (28)

Catherine Parr also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine Parr ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature". (29)

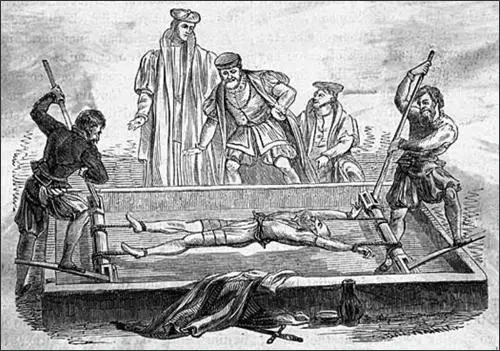

Bishop Stephen Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." (30) Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. (31)

Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. (32) It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. (33)

Anne Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. (34) Also executed at the same time was John Lascelles, John Hadlam and John Hemley. (35) John Bale wrote that “Credibly am I informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, and abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements both declared wherein the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents." (36)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII after the execution of Anne Askew and raised concerns about his wife's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine Parr and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible. (37)

Henry then went to see Catherine to discuss the subject of religion. Probably, aware what was happening, she replied that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." (38) Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." (39) Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. (40)

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. (41) However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women." (42)

The Levellers

During the English Civil War a group of men, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn, John Wildman, Thomas Prince, and Edward Sexby were described as Levellers. In demonstrations they wore sea-green scarves or ribbons. (43) In September, 1647, William Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. However, they had not demanded the vote for women. (44)

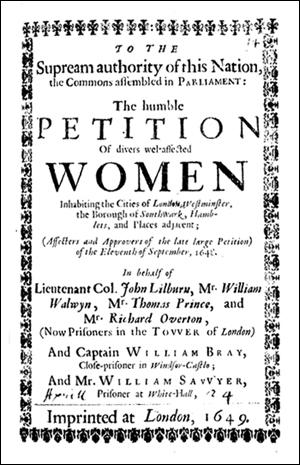

The leaders of the Levellers were imprisoned on the orders of Oliver Cromwell. The movement called for the release of these men. This included Britain's first ever all-women petition, that was supported by over 10,000 signatures. This group, led by Elizabeth Lilburne, Mary Overton and Katherine Chidley, presented the petition to the House of Commons on 25th April, 1649. (45) They justified their political activity on the basis of "our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportionable share in the freedoms of this commonwealth". (46)

MPs reacted intolerantly, telling the women that "it was not for women to petition; they might stay home and wash their dishes... you are desired to go home, and look after your own business, and meddle with your housewifery". One woman replied: "Sir, we have scarce any dishes left us to wash, and those we have not sure to keep." When another MP said it was strange for women to petition Parliament one replied: "It was strange that you cut off the King's head, yet I suppose you will justify it." (47)

The following month Elizabeth Lilburne produced another petition: "That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House. Have we not an equal interest with the men of this nation in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and other the good laws of the land? Are any of our lives, limbs, liberties, or goods to be taken from us more than from men, but by due process of law and conviction of twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood? Would you have us keep at home in our houses, when men of such faithfulness and integrity as the four prisoners, our friends in the Tower, are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by soldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children, and families?" (48)

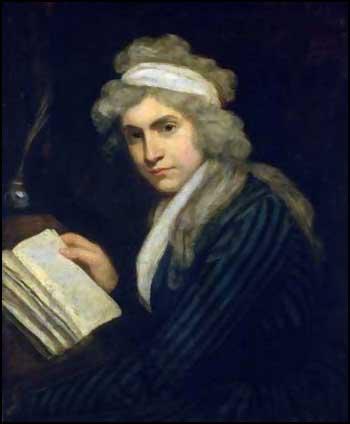

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft, the eldest daughter of Edward Wollstonecraft and Elizabeth Dixon Wollstonecraft, was born in Spitalfields, London on 27th April 1759. At the time of her birth, Wollstonecraft's family was fairly prosperous: her paternal grandfather owned a successful Spitalfields silk weaving business and her mother's father was a wine merchant in Ireland. (49)

Mary did not have a happy childhood. Claire Tomalin, the author of The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (1974) has pointed out: "Mary's father was sporadically affectionate, occasionally violent, more interested in sport than work, and not to be relied on for anything, least of all for loving attention. Her mother was indolent by nature and made a darling of her first-born, Ned, two years older than Mary; by the time the little girl had learned to walk in jealous pursuit of this loving pair, a third baby was on the way. A sense of grievance may have been her most important endowment." (50)

In 1765 her grandfather died and her father, his only son, inherited a large share of the family business. He sold the business and purchased a farm at Epping. However, her father had no talent for farming. According to Mary, he was a bully, who abused his wife and children after heavy drinking sessions. She later recalled that she often had to intervene to protect her mother from her father's drunken violence (51) William Godwin claims this had a major impact on the development of her personality as Mary "was not formed to be the contented and unresisting subject of a despot". (52)

Mary had several younger brothers and sisters: Henry (1761), Eliza (1763), Everina (1765), James (1768) and Charles (1770). When she was nine years of age, the family moved to a farm in Beverley where Mary received a couple years at the local school, where she learned to read and write. It was the only formal schooling she was to receive. Ned, on the other hand, received a good education, with the hope that eventually he would become a lawyer. Mary was upset by the amount of attention Ned received and said of her mother "in comparison with her affection for him, she might be said not to love the rest of her children". (53)

In 1673 Mary became friends with another fourteen-year-old, girl, Jane Arden. Her father, John Arden, was a highly educated man who gave public lectures on natural philosophy and literature. Arden also gave lessons to his daughter and her new friend. (54) "Sensitive about the failings she was beginning to perceive in her own family, and contrasting them with the dignified, sober and well-read Ardens, Mary envied Jane her entire situation and attached herself determinedly to the family." (55)

Mary and Jane had a argument and stopped seeing each other. However, they did keep in contact by letter: "Before I begin I beg pardon for the freedom of my style. If I did not love you I should not write so; I have a heart that scorns disguise, and a countenance which will not dissemble: I have formed romantic notions of friendship. I have been once disappointed - I think if I am a second time I shall only want some infidelity in a love affair, to qualify me for an old maid, as then I shall have no idea of either of them. I am a little singular in my thoughts of love and friendship; I must have the first place or none. - I own your behaviour is more according to the opinion of the world, but I would break such narrow bounds" (56)

In 1774 Edward Wollstonecraft's financial situation forced the family to move again. This time they returned to a house in Hoxton. Her brother, Ned, was being trained as a lawyer, and used to come home at weekends. Mary continued to have a bad relationship with her brother and constantly undermined her confidence. She later recalled that he took "particular pleasure in tormenting and humbling me". (57)

While in London she met Fanny Blood. "She was conducted to the door of a small house, but furnished with peculiar neatness and propriety. The first object that caught her sight, was a young woman of slender and elegant form... busily employed in feeding and managing some children, born of the same parents, but considerably her inferior in age. The impression Mary received from this spectacle was indelible; and before the interview was concluded, she had taken, in her heart, the vows of eternal friendship." (58)

Mary identified closely with her new friend: "Fanny was eighteen to Mary's sixteen, slim and pretty and set apart from the rest of her family by her manners and talents. Mary could see in her a mirror-image of herself: an eldest daughter, superior to her surroundings, often in charge of a brood of little ones, with an improvident and a drunken father and a mother charming and gentle but quite broken in spirit." (59)

After two years in London the family moved to Laugharne in Wales but Mary continued to correspond with Fanny, who had been promised in marriage to Hugh Skeys, who was living in Lisbon. Mary said in one letter that her feeling for her "resembled a passion" and was "almost (but not quite) that of an intending husband". Mary explained to Jane Arden that her relationship with Fanny was difficult to explain: "I know my resolution may appear a little extra-ordinary, but in forming it I follow the dictates of reason as well as the bent of my inclination." (60)

Mary's mother died in 1782. She now went to live with Fanny Blood and her pa rents at Waltham Green. Her sister Eliza, married Meredith Bishop, a boat-builder from Bermondsey. In August, 1783, after the birth of her first child, she suffered a mental breakdown and Mary was asked to look after her. When she arrived at her sister's home Mary found Eliza in a very disturbed state. Eliza explained that she had "been very ill-used by her husband".

Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, explaining that "Bishop cannot behave properly - and those who attempt to reason with him must be mad or have very little observation... My heart is almost broken with listening to Bishop while he reasons the case. I cannot insult him with advice which he would never have wanted if he was capable of attending to it." In January, 1784, the two sisters escaped from Bishop and went to live under a false name in Hackney. (61)

A few months later Mary Wollstonecraft opened a school in Newington Green, with her sister Eliza and a friend, Fanny Blood. Soon after arriving in the village, Mary made friends with Richard Price, a minister at the local Dissenting Chapel. Price and his friend, Joseph Priestley, were the leaders of a group of men known as Rational Dissenters. Price told her that the "love of God meant attacking injustice". (62)

Price had written several books including the very influential Review of the Principal Questions of Morals (1758) where he argued that individual conscience and reason should be used when making moral choices. Price also rejected the traditional Christian ideas of original sin and eternal punishment. As a result of these religious views, some Anglicans accused Rational Dissenters of being atheists. (63)

Fuseli was forty-seven and Mary twenty-nine. He was recently married to his former model, Sophia Rawlins. Fuseli shocked his friends by constantly talking about sex. Mary later told William Godwin that she never had a physical relationship with Fuseli but she did enjoy "the endearments of personal intercourse and a reciprocation of kindness, without departing in the smallest degree from the rules she prescribed to herself". (69)

Mary fell deeply in love with Fuseli: "From him Mary learnt much about the seamy side of life... Obviously there was a time when they were in love with one another, and playing with fire; the increase of Mary's love to the point where it became torture to her is hard to explain if it remained at all times entirely platonic." (70) Mary wrote that she was enraptured by his genius, "the grandeur of his soul, that quickness of comprehension, and lovely sympathy". She proposed a platonic living arrangement with Fuseli and his wife, but Sophia rejected the idea and he broke off the relationship with Wollstonecraft. (71)

In 1788 Joseph Johnson and Thomas Christie established the Analytical Review. The journal provided a forum for radical political and religious ideas and was often highly critical of the British government. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote articles for the journal. So also did the scientist, Joseph Priestley, the philosopher, Erasmus Darwin, the poet William Cowper, the moralist William Enfield, the physician John Aikin, the author Anna Laetitia Barbauld; the Unitarian minister William Turner; the literary critic James Currie; the artist Henry Fuseli; the writer Mary Hays and the theologian Joshua Toulmin. (72)

Mary and her radical friends welcomed the French Revolution. In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. "I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priest giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience." (73)

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. He also attacked political activists such as Major John Cartwright, John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Walker, who had formed the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation that promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. (74)

Burke attacked the dissenters who were wholly "unacquainted with the world in which they are so fond of meddling, and inexperienced in all its affairs, on which they pronounce with so much confidence". He warned reformers that they were in danger of being repressed if they continued to call for changes in the system: "We are resolved to keep an established church, an established monarchy, an established aristocracy, and an established democracy; each in the degree it exists, and in no greater." (75)

Joseph Priestley was one of those attacked by Burke, pointed out: "If the principles that Mr Burke now advances (though it is by no means with perfect consistency) be admitted, mankind are always to be governed as they have been governed, without any inquiry into the nature, or origin, of their governments. The choice of the people is not to be considered, and though their happiness is awkwardly enough made by him the end of government; yet, having no choice, they are not to be the judges of what is for their good. On these principles, the church, or the state, once established, must for ever remain the same." Priestley went on to argue that these were the principles "of passive obedience and non-resistance peculiar to the Tories and the friends of arbitrary power." (76)

Mary Wollstonecraft also felt that she had to respond to Burke's attack on her friends. Joseph Johnson agreed to publish the work and decided to have the sheets printed as she wrote. According to one source when "Mary had arrived at about the middle of her work, she was seized with a temporary fit of topor and indolence, and began to repent of her undertaking." However, after a meeting with Johnson "she immediately went home; and proceeded to the end of her work, with no other interruption but what were absolutely indispensable". (77)

The pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man not only defended her friends but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society. This included the slave trade and way that the poor were treated. In one passage she wrote: "How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre." (78)

The pamphlet was so popular that Johnson was able to bring out a second edition in January, 1791. Her work was compared to that of Tom Paine, the author of Common Sense. Johnson arranged for her to meet Paine and another radical writer, William Godwin. Henry Fuseli's friend, William Roscoe, visited her and he was so impressed by her that he commissioned a portrait of her by John Williamson. "She took the trouble to have her hair powdered and curled for the occasion - a most unrevolutionary gesture - but was not very pleased with the painter's work." (79)

In 1791 the first part of Paine's Rights of Man was published. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread." (80)

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act." (81)

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy. (82)

Mary Wollstonecraft's publisher, Joseph Johnson, suggested that she should write a book about the reasons why women should be represented in Parliament. It took her six weeks to write Vindication of the Rights of Women. She told her friend, William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject. Do not suspect me of false modesty. I mean to say, that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word." (83)

In the book Mary Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." She added: " I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves". (84)

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. One critic described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing.

Edmund Burke continued his attack on the radicals in Britain. He described the London Corresponding Society and the Unitarian Society as "loathsome insects that might, if they were allowed, grow into giant spiders as large as oxen". King George III issued a proclamation against seditious writings and meetings, threatening serious punishments for those who refused to accept his authority.

In November, 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to move to Paris in an effort to get away from her unhappy love affair with Henry Fuseli: "I intend no longer to struggle with a rational desire, so have determined to set out for Paris in the course of a fortnight or three weeks." She joked that "I am still a spinster on the wing... At Paris I might take a husband for the time being, and get divorced when my truant heart longed again to nestle with old friends." (85)

Mary arrived in Paris on 11th December at the start of the trial of King Louis XVI. She stayed in a small hotel and watched events from the window of her room: "Though my mind is calm, I cannot dismiss the lively images that have filled my imagination all the day... Once or twice, lifting my eyes from the paper, I have seen eyes glare through a glass-door opposite my chair, and bloody hands shook at me... I am going to bed - and, for the first time in my life, I cannot put out the candle." (86)

Also in Paris at this time was Tom Paine, William Godwin, Joel Barlow, Thomas Christie, John Hurford Stone, James Watt and Thomas Cooper. She also met the poet, Helen Maria Williams. Mary wrote to her sister, Everina, that "Miss Williams has behaved very civilly to me, and I shall visit her frequently, because I rather like her, and I meet French company at her house. Her manners are affected, yet her simple goodness of her heart continually breaks through the varnish, so that one would be more inclined, at least I should, to love than admire her." (87)

In March 1793 Mary met the writer, Gilbert Imlay, whose novel, The Emigrants, had just been published. The book appealed to Mary "because it advocated divorce and contained a portrait of a brutal and tyrannical husband". Mary was thirty-four and Imlay was five years older. "He was a handsome man, tall, thin and easy in his manner". Wollstonecraft was immediately attracted to him and described him as "a most natural, unaffected creature". (88)

William Godwin, who witnessed the relationship while he was in Paris, claims that her personality changed during this period. "Her confidence was entire; her love was unbounded. Now, for the first time in her life, she gave a loose to all the sensibilities of her nature... Her whole character seemed to change with a change of fortune. Her sorrows, the depression of her spirits, were forgotten, and she assumed all the simplicity and the vivacity of a youthful mind... She was playful, full of confidence, kindness and sympathy. Her eyes assumed new lustre, and her cheeks new colour and smothness. Her voice became cheerful; her temper overflowing with universal kindness: and that smile of bewitching tenderness from day to day illuminated her countenance, which all who knew her will so well recollect." (89)

Mary decided to live with Imlay. She wrote about those "sensations that are almost too sacred to be alluded to". The German revolutionary, George Forster in July 1793, met Mary soon after her relationship with Imlay began. "Imagine a five or eight and twenty year old brown-haired maiden, with the most candid face, and features which were once beautiful, and are still partly so, and a simple steadfast character full of spirit and enthusiasm; particularly something gentle in eye and mouth. Her whole being is wrapped up in her love of liberty. She talked much about the Revolution; her opinions were without exception strikingly accurate and to the point." (90)

Mary gave birth to a girl on 14th May 1794. She named her Fanny after her first love, Fanny Blood. She wrote to a friend about how tenderly she and Gilbert loved the new child: "Nothing could be more natural or easy than my labour. My little girl begins to suck so manfully that her father reckons saucily on her writing the second part of the Rights of Women." (91)

In August 1794, Gilbert told Mary he had to go to London on business and he would make arrangements for her to join him in a few months. In reality he had deserted her. "When I first received your letter, putting off your return to an indefinite time, I felt so hurt that I know not what I wrote. I am now calmer, though it was not the kind of wound over which time has the quickest effect; on the contrary, the more I think, the sadder I grow... What sacrifices have you not made for a woman you did not respect! But I will not go over this ground. I want to tell you that I do not understand you." (92)

Mary returned to England in April 1795 but Imlay was unwilling to live with her and keep up appearances like a conventional husband. Instead he moved in with an actress "exposing Mary to public humiliation and forcing her to acknowledge openly the failure of her brave social experiment... it is one thing to defy the opinion of the world when you are happy, another altogether to endure it when you are miserable." Mary found it especially humiliating that his "desire for her had lasted scarcely more than a few months". (93)

One night in October 1795, she jumped off Putney Bridge into the Thames. By the time she had floated two hundred yards downstream she was seen by a couple of waterman who managed to pull her out of the river. She later wrote: "I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured." (94)

Joseph Johnson managed to persuade her return to writing. In January 1796 he published a pamphlet entitled Letters Written During a Short Residence in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Mary was a good travel writer and provided some good portraits of the people she met in these countries. From a literary standpoint it was probably Wollstonecraft's best book. One critic commented that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author this appears to me to be the book". (95)

In March 1796, Mary wrote to Gilbert Imlay to tell them that she had finally accepted that their relationship was over: "I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell... I part with you in peace". (96) Mary was now open to starting another relationship. She was visited several times by the artist, John Opie, who had recently obtained a divorce from his wife. Robert Southey also showed interest and told a friend that she was the person he liked best in the literary world. He said her face was marred only by a slight look of superiority, and that "her eyes are light brown, and, though the lid of one of them is affected by a little paralysis, they are the most meaning I ever saw". (97)

Her friend, Mary Hays, invited her to a small party where renewed her acquaintance with the philosopher, William Godwin. Although aged 40 he was still a bachelor and for most of his life he had shown little interest in women. He had recently published Enquiry into Political Justice and William Hazlitt had commented that Godwin "blazed as a sun in the firmament of reputation". (98)

The couple enjoyed going to the theatre together and going to dinner with painters, writers and politicians, where they enjoyed discussing literary and political issues. Godwin later recalled: "The partiality we conceived for each other, was in that mode, which I have always regarded as the purest and most refined of love. It grew with equal advances in the mind of each. It would have been impossible for the most minute observer to have said who was before, and who was after... I am not conscious that either party can assume to have been the agent or the patient, the toil-spreader or the prey, in the affair... I found a wounded heart... and it was my ambition to heal it." (99)

Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin in March, 1797 and soon afterwards, a second daughter, Mary, was born. The baby was healthy but the placenta was retained in the womb. The doctor's attempt to remove the placenta resulted in blood poisoning and Mary died on 10th September, 1797.

Women and Chartism

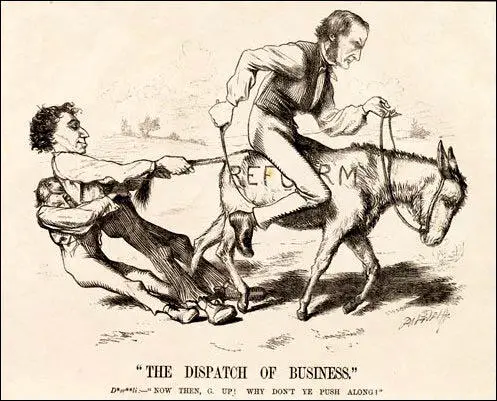

In June 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, Henry Vincent, John Roebuck and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands. (100)

(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime. (ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period." (101)

Although many leading Chartists believed in votes for women, it was never part of the Chartist programme. When the People's Charter was first drafted by the leaders of the London Working Men's Association, a clause was included that advocated the extension of the franchise to women. This was eventually removed because some members believed that such a radical proposal "might retard the suffrage of men". As one author pointed out, "what the LWMA feared was the widespread prejudice against women entering what was seen as a man's world". (102)

In most of the large towns in Britain, Chartist groups had women sections. The East London Female Patriotic Association published its objectives in October, 1839, and made it clear that they wanted to "unite with our sisters in the country, and to use our best endeavours to assist our brethren in obtaining universal suffrage". The organisation made the point that they would use their power as managers of the household to obtain the vote for their men by "to deal as much as possible with those shopkeepers who are favourable to the People's Charter". (103)

These women's groups were often very large, the Birmingham Charter Association for example, had over 3,000 female members. (104) The Northern Star reported on 27th April, 1839, that the Hyde Chartist Society contained 300 men and 200 women. The newspaper quoted one of the male members as saying that the women were more militant than the men, or as he put it: "the women were the better men". (105)

Elizabeth Hanson formed the Elland Female Radical Association in March, 1838. She argued "it is our duty, both as wives and mothers, to form a Female Association, in order to give and receive instruction in political knowledge, and to co-operate with our husbands and sons in their great work of regeneration." (106) She became one of the movement's most effective speakers and one newspaper reported she "melted the hearts and drew forth floods of tears". (107)

In 1839 Elizabeth gave birth to a son, who she named after Feargus O'Connor. She continued to be involved in the campaign for universal suffrage.Her husband, Abram Hanson, acknowledged the importance of "the women who are the best politicians, the best revolutionists, and the best political economists... should the men fail in their allegiance the women of Elland, who had sworn not to breed slaves, had registered a vow to do the work of men and women." (108)

Susanna Inge was another important figure in the Chartist movement. As she explained in an article for The Northern Star in July, 1842. "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved". She went on to urge women to “assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also". (109)

In October 1842, Susanna Inge and Mary Ann Walker attempted to establish a Female Chartist Association. Inge argued that in time women should be given the vote. However, she felt before this could happen women "ought to be better educated, and that, if she were, so far as mental capacity, she would in every respect be the equal of man”. (110)

This plan to form a Female Chartist Association was criticised by some male Chartists. One declared that he "did not consider that nature intended women to partake of political rights". He argued that women were "more happy in the peacefulness and usefulness of the domestic hearth, than in coming forth in public and aspiring after political rights". (111)

It was also suggested that if a "young gentleman" might try "to influence her vote through his sway over her affection". Mary Ann Walker responded by claiming that "she would treat with womanly scorn, as a contemptible scoundrel, the man who would dare to influence her vote by any undue and unworthy means; for if he were base enough to mislead her in one way, he would in another.” (112)

On 6th November, 1842, The Sunday Observer reported that Susanna Inge was giving a lecture at the National Charter Hall in London. With her was another woman, Emma Matilda Miles. The newspaper suggested that the women had joined in response to the arrest and punishment of John Frost after the Newport Uprising. It would seem that Inge was a supporter of the Physical Force movement. (113)

Susanna Inge was not content to be a mere propagandist. She had ideas on how Chartism might be better organised. In one letter to the The Northern Star she suggested that every Chartist locality should have its byelaws and plan of organisation hung in a prominent place, that these should be read before every meeting, and that any officer who failed to abide by them should be called to account. (114)

Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force chartists, was not in favour of women having equal political rights with men. He claimed that the role of the woman was to be a "housewife to prepare meals, to wash, to brew, and look after my comforts, and the education of my children." (115) Anna Clark has pointed out that O'Connor demanded "entry into the public sphere for working men" and "the privileges of domesticity for their wives". (116)

Susanna Inge wrote letters to O’Connor's newspaper complaining about his views. These were rejected for publication and in July, 1843, it admitted that Inge "very much questions the propriety or right of Mr O’Connor to name or suggest to the people, through the medium of the Northern Star, any person to fill any office whatever" as "it is not according to her ideas of democracy." The newspaper dismissed her comments with the words: "We dare say Miss Inge is greatly in love with her ideas of democracy; and so she ought, for we fancy they will suit nobody else” (117)

One of the most militant women's groups was the Female Political Union of Newcastle. They completely rejected the idea that they should not become involved in politics. "We have been told that the province of women is her home, and that the field of politics should be left to men; this we deny. It is not true that the interests of our fathers, husbands, and brothers, ought to be ours? If they are oppressed and impoverished, do we not share those evils with them? If so, ought we not to resent the infliction of those wrongs upon them? We have read the records of the past, and our hearts have responded to the historian's praise of those women, who struggled against tyranny and urged their countrymen to be free or die." (118)

In 1840, R. J. Richardson, a Chartist from Salford, wrote the pamphlet, The Rights of Women, while he was in Lancaster Prison. "If a woman is qualified to be a queen over a great nation, armed with power of nullifying the powers of Parliament. If it is to be admissible that the queen, a woman, by the constitution of the country can command, can rule over a nation, then I say, women in every instance ought not to be excluded from her share in the executive and legislative power of the country." (119)

William Lovett argued that women's rights should be equal to those of men. However, Lovett added that woman's duties were different from that of her male partner. "His being to provide for the wants and necessaries of the family; hers to perform the duties of the household." However, when in March 1841, Lovett, Henry Hetherington and Henry Vincent, launched the National Association, the new organisation included women's suffrage in their programme. (120)

It has been estimated that up to 20% of those who signed Chartist petitions were women. As well as holding meetings they fully participated at open-air rallies. Henry Vincent reports that when he was addressing a meeting in Cirencester he was pelted with stones. A group of local women gave one of the culprits "a good thrashing". A similar incident involving an anti-Chartist heckler occurred at Stockton-upon-Tees, and women also "occasionally featured among Chartists charged with public order offences." (121)

William Pattison, a leading Chartist in Scotland, explained that it was very difficult for women to play an active role in politics: “He knew that the females were maligned, more perhaps than any other party, for taking a part in politics. He did assure them that the position which females ought to occupy, was the duties of home and the family circle. But, under the present system of legislation, instead of being allowed to remain at home, they were forced to go and toil in the factory for their existence.” (122)

The main argument put forward by Chartist women was that their husbands should earn enough to support them and their children at home. Female Chartists were concerned with women and children replacing men in factories. Three leading women chartists, Elizabeth Pease, Jane Smeal and Anne Knight, were all Quakers. These women had also been involved in the anti-slavery campaign.

Pease pointed out in a letter to a friend why she was active in the Chartist movement: "The grand principle of the natural equality of man - a principle alas almost buried, in the land, beneath the rubbish of an hereditary aristocracy and the force of a state religion. Working people are driven almost to desperation by those who consider they are but chattels made to minister to their luxury and add to their wealth." (123)

Women who spoke at Chartist meetings were described in the national press as "she-orators". The Sunday Observer reported on a meeting where Emma Matilda Miles told the audience: "It was the duty of women to step forth, and, in all the majesty of her native dignity, assist her brother slaves in effecting the political redemption of the country. It was not ambition, it was not vanity that induced her to become a public woman; no, it was the oppression which had fallen upon every poor man's house that made her speak.... She did not doubt the ultimate success of Chartism any more than she doubted her own existence; but then it would not, as she said, be granted by the justice - no, it must be extorted from the fears of their oppressors". (124)

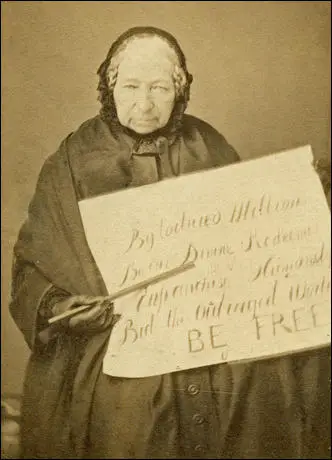

Anne Knight was the most outspoken of the women in the movement. She was concerned about the way women campaigners were treated by some of the male leaders in the organisation. Knight criticised them for claiming "that the class struggle took precedence over that for women's rights". (125) Knight wrote "can a man be free, if a woman be a slave." (126) In a letter published in the Brighton Herald in 1850 she demanded that the Chartists should campaign for what she described as "true universal suffrage". (127)

An anonymous leaflet was published in 1847. It has been persuasively argued that the author of the work was Anne Knight. In argued: "Never will the nations of the earth be well governed, until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws". (128)

Knight also became involved in international politics. In 1848 she was the first French government elected by universal manhood suffrage repressed freedom of association. The decree prohibited women from forming clubs or attending meetings of associations. Knight published a pamphlet criticising this action: "Alas, my brother, is it then true that thy eloquent voice has been heard in the heart of the National Assembly expressing a sentiment so contrary to real republicanism? Can it be that thou hast really protested not only against women's rights to form clubs but also against their right to attend clubs formed by men?" (129)

placard reads: "By tortured millions, By the Divine Redeemer,

Enfranchise Humanity, Bid the Outraged World, BE FREE".

At a conference on world peace held in 1849, Anne Knight met two of Britain's reformers, Henry Brougham and Richard Cobden. She was disappointed by their lack of enthusiasm for women's rights. For the next few months she sent them several letters arguing the case for women's suffrage. In one letter to Cobden she argued that it was only when women had the vote that the electorate would be able to pressurize politicians into achieving world peace. (130)

Anne Knight established the Sheffield Female Political Association. Their first meeting was held in Sheffield in February, 1851. Later that year it published an "Address to the Women of England". This was the first petition in England that demanded women's suffrage. It was presented to the House of Lords by George Howard, 7th Earl of Carlisle. (131) The following year she was "forbidden to vote for the man who inflicts the laws I am compelled to obey - the taxes I am compelled to pay". She added that "taxation without representation is tyranny". (132)

Caroline Norton

Caroline Sheridan, the daughter of Thomas Sheridan, colonial official, and his wife, Caroline Henrietta Callender Sheridan, was born on 22nd March 1808. Her grandfather was Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright and politician. Caroline's father died when she was eight years old, leaving the family in serious financial problems. (133)

For a while Caroline lived with her uncle, the writer, Charles Sheridan. At an early age she developed literary ambitions. She spent time with her uncle and at the age of eleven she wrote: "I invariably left his study with an enthusiastic determination to write a long poem of my own." (134)

Caroline was considered to be a high spirited and rather uncontrollable. "She even looked strange when she was young, with huge dark eyes and a great mass of wild black hair. Her habit of lowering her head and looking at people through her thick black eyelashes was thought of as furtive. People were not comfortable with her nor she with them. In spite of her quick tongue she was actually quite shy." (135)

In 1824, finding her sixteen-year-old daughter too difficult to manage, Mrs Sheridan sent her to a boarding-school at Shalford. The girls at the school were invited to Wonersh Park, the seat of the local landowner, William Norton (Lord Grantley). Caroline was seen by Grantley's younger brother, George Norton, and informed her governess of his intention to propose marriage to her. Norton put his proposal into writing and Caroline's mother accepted his offer but insisted that he waited three years. (136)

Diane Atkinson, the author of The Criminal Conversation of Mrs Norton (2013) has argued that might have been a good reason why Caroline's mother had suggested that Norton should not marry her daughter straight away: "Caroline was horrified at the prospect of marrying a man she barely remembered seeing, but it was her mother's right and duty to secure a husband for her and there had been no other interest. Perhaps Mrs Sheridan was playing for time, hoping someone else would come along." (137)

Mary Shelley, who knew her well, later recalled that she could understand why Norton wanted to marry her: "I never saw a woman I thought so fascinating. Had I been a man I should certainly have fallen in love with her... I would have been spellbound, and had she taken the trouble, she might have wound me round her finger. There is something in the pretty way in which her witticisms glide, as it were, from her lips, that is charming." (138)

Although she did not love Norton, Caroline agreed to help her mother's financial situation by marrying him. The other reason she married Norton was the fear that she would never receive another offer: "The only misfortune I ever particularly dreaded was living and dying a lonely old maid... An old maid is never anyone's first object therefore I object to that situation." (139)

The marriage took place in 1827 when Caroline was nineteen. The marriage was a disaster from the outset, mainly because they were completely incompatible. "George Norton was slow, rather dull, jealous, and obstinate; Caroline was quick-witted, vivacious, flirtatious, and egotistical." They also disagreed passionately about politics. Norton was a hard-line Tory MP, whereas Caroline had developed liberal opinions. (140)

Caroline Norton later recalled: "We had been married about two months, when, one evening, after we had all withdrawn to our apartments, we were discussing some opinion Mr. Norton had expressed; I said, that I thought I had never heard so silly or ridiculous a conclusion. This remark was punished by a sudden and violent kick; the blow reached my side; it caused great pain for several days, and being afraid to remain with him, I sat up the whole night in another apartment."

This violent behaviour continued: "Four or five months afterwards, when we were settled in London, we had returned home from a ball; I had then no personal dispute with Mr. Norton, but he indulged in bitter and coarse remarks respecting a young relative of mine, who, though married, continued to dance - a practice, Mr. Norton said, no husband ought to permit. I defended the lady spoken of when he suddenly sprang from the bed, seized me by the nape of the neck, and dashed me down on the floor. The sound of my fall woke my sister and brother-in-law, who slept in a room below, and they ran up to the door. Mr. Norton locked it, and stood over me, declaring no one should enter. I could not speak - I only moaned. My brother-in-law burst the door open and carried me downstairs. I had a swelling on my head for many days afterwards." (141)

Caroline had three children, Fletcher (1829), Brinsley (1831) and William (1833). The couple constantly argued about politics. They disagreed intensely on virtually all the main political issues of the day. Caroline, like her grandfather, was a Whig who favoured extensive social reform. George Norton was the Tory MP from Guildford, who had opposed measures favoured by Caroline such as Catholic Emancipation and Parliamentary Reform. (142)

Caroline Norton had always been interested in writing and in 1829 her long poem The Sorrows of Rosalie was published. This was followed by The Undying One in 1830. As a result of these poems, Caroline was invited to become editor of La Belle Assemblee and Court Magazine. Her close friends during this period included Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Mary Shelley, Fanny Kemble, Benjamin Disraeli, Edward Trelawney and Samuel Rogers.

In the 1830 General Election, Norton lost his seat in the House of Commons. His brother, William Norton, argued that the main reason for this was that he had not been around enough for the voters to see him. Caroline Norton wrote to her sister, suggesting that he was unlucky to be defeated: "He assures me that although thrown out he was the popular candidate... that all those who voted against him did it with tears." (143)

Earl Grey, the leader of the Whigs, became Prime Minister. Norton asked his wife if she could use her contacts with the new administration to obtain for him a well-paid government post. In 1831 Caroline met William Lamb, Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary, and he arranged for George Norton to be appointed as a magistrate in the Lambeth Division of the Metropolitan Police Courts, with the generous salary of £1,000 a year. (144)

Lord Melbourne and Caroline Norton became close friends. Melbourne, a widower, had a reputation as a womanizer, and rumours began to circulate about his relationship with Caroline. Melbourne's biographer, Peter Mandler, has pointed out that the relationship "achieved a happiness that had escaped him earlier... it is less likely to have been sexual, but it provided Melbourne with the same emotional reassurance, while allowing him to play mild games of hot-and-cold flirtation and discipline". (145)

Friends pointed out that in her twenties "the dark wildness of her younger days had been replaced by a confidence and control observers found remarkable". Her intellectual abilities also impressed people who met her: "She was bold in her opinions and brilliant in her arguments and never held back from either." (146) Charles Sumner, commented that Caroline Norton combined "the grace and ease of a woman with a strength and skill of which any man might be proud." (147)

George Norton heard rumours about the relationship but did not intervene as he hoped he would benefit from Caroline's friendship with the Home Secretary. Claire Tomalin has argued: "Lord Melbourne was nearly thirty years her senior; his wife (Caroline Lamb) had lately died; and he was a man peculiarly susceptible to the delights of a quasi-paternal relationship. Caroline Norton offered him beauty, charm, a sharp interest in everything that interested him and something like an eighteenth-century sense of fun; more, she idealized him for his urbanity, his power, wealth and well-preserved good looks." (148)

George Norton continued to beat Caroline and after one row in the summer of 1833 she locked herself in the drawing-room. This infuriated George who hurled himself at the door like a battering ram until it not only caved in but the whole framework of the door came away from the wall. Although she was seven months pregnant he "manhandled her down the stairs, punching and slapping her". Eventually, the servants were forced to restrain him. (149)

In 1835 Norton took the opportunity when his wife was visiting her sister to take their three children out of the house, and put them under the charge of a cousin, Miss Vaughan, who refused to let their mother have access to them. Caroline took refuge with her own family, and then found out the dreadful position in which the law placed her. She had nor rights concerning her children, and might never see them again until they were of age, without permission from her husband. (150)

Caroline Norton pointed out that even the money she earned as a writer belonged to her husband: "An English wife cannot legally claim her own earnings. Whether wages for manual labour, or payment for intellectual exertion, whether she weed potatoes, or keep a school, her salary is the husband's; and he could compel a second payment, and treat the first as void, if paid to the wife without his sanction." (151)

Lord Melbourne became prime minister in March, 1835. Norton, who had serious financial problems, told Caroline that he intended to sue Lord Melbourne for adultery. Norton then approached Melbourne and suggested that he should be paid £1,400 to avoid a politically damaging court case. Melbourne, who denied that he had been having a sexual relationship with Caroline, refused to give Norton any money.

George Norton now approached the Tory peer, William Best, 1st Lord Wynford, about the matter. Wynford believed that a sexual scandal involving Melbourne would bring the Whig government down and advised Norton to bring a suit charging the prime minister with "alienating his wife's affections". Norton now began to leak stories to the Tory press. Between March and June, 1835 a number of articles appeared suggesting that Melbourne was having an affair with Caroline. It was also suggested that other progressives such as Thomas Duncombe, Edward Trelawny and William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire, had also had affairs with Caroline. (152)

Barnard Gregory, the publisher of The Satirist, took up the case. On 29th May 1836, the newspaper reported that George Norton had known for a long time of "the intimacy subsisting between his Lady and Lord Melbourne". (153) Another newspaper, included not only Caroline but her sisters in all the innuendo and speculated openly about their reputations, mentioning in the process every gentleman who had ever been seen with them." (154)

George Norton told Caroline that he intended to go to court over the issue. When she informed Lord Melbourne of the bad news he claimed that this was the end of his political career. She said that she would never forget "the shrinking from me and my burdensome and embarrassing distress". (155)

Melbourne offered his resignation but William IV refused to accept it. However, he was advised to break off all contact with Caroline Norton. When it became known that Lord Wynford was responsible for Norton's action against Melbourne, even some Tory newspapers defended Melbourne. One Tory was quoted as saying that the case brought "disgrace to our party".

In June 1836 Norton brought a case for criminal conversation between Melbourne and his wife to the courts, suing Melbourne for £10,000 in damages for adultery. The case began on 22nd June 1836. Two of George Norton's servants gave evidence that they believed Caroline and Lord Melbourne had been having an affair. She had been prepared for lies but what appalled her was "the loathsome coarseness and invention of circumstances which made me a shameless wretch." One maid testified that she had been "painting her face and sinning with various gentlemen" in the same week that she gave birth to her third child. (156)

Three letters written by Melbourne to Caroline were presented in court. The contents of the three letters were very brief: (i) "I will call about half past four". (ii) "How are you? I shall not be able to come today. I shall tomorrow." (iii) "No house today. I will call after the levee. If you wish it later let me know. I will then explain about going to Vauxhall." Sir W. Follett, George Norton's counsel, argued that these letters showed "a great and unwarrantable degree of affection, because they did not begin and end with the words My dear Mrs. Norton."

One pamphlet reported: "One of the servants had seen kisses pass between the parties. She had seen Mrs Norton's arm around Lord Melbourne's neck - had seen her hand upon his knee, and herself kneeling in a posture. In that room (her bedroom) Mrs Norton has been seen lying on the floor, her clothes in a position to expose her person. There are other things too which it is my faithful duty to disclose. I allude to the marks from the consequences of the intercourse between the two parties. I will show you that these marks were seen upon the linen of Mrs Norton." (157)

The jury was unimpressed with the evidence presented in court and Follett's constant demands for the "payment of damages to his client" and Norton's witnesses were unreliable. Without calling any of the witnesses who would have proved Caroline's innocence the jury threw the case out. However, the case had destroyed Caroline's reputation and ruined and her friendship with Lord Melbourne. He refused to see her and Caroline wrote to him that it had destroyed her hope of "quietly taking my place in the past with your wife Mrs Lamb." (158)

Despite Norton's defeat in court, he still had the power to deny Caroline access to her children. She pointed out: "After the adultery trial was over, I learnt the law as to my children - that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them - for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr. Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney. What I suffered on my children's account, none will ever know or measure. Mr. Norton held my children as hostages, he felt that while he had them, he still had power over me that nothing could control." (159)

Caroline wrote to Lord Melbourne, who continued to refuse to see her in case it caused another political scandal: "God forgive you, for I do believe no one, young or old, ever loved another better than I loved you... I will do nothing foolish or indiscreet - depend on it - either way it is all a blank to me. I don't much care how it ends... I have always the memory of how you received me that day, and I have the conviction that I have no further power than he allows me, over my boys. You and they were my interests in life. No future can ever wipe out the past - nor renew it." (160)

Caroline wrote a pamphlet explaining the unfairness of this entitled The Natural Claim of a Mother to the Custody of her Children as affected by the Common Law Rights of the Father (1837): Caroline argued that under the present law, a father had absolute rights and a mother no rights at all, whatever the behaviour of the husband. In fact, the law gave the husband the legal right to desert his wife and hand over his children to his mistress. For the first time in history, a woman had openly challenged this law that discriminated against women. (161)

Caroline Norton now began a campaign to get the law changed. Sir Thomas Talfourd, the MP for Reading agreed to Caroline's request to introduce a bill into Parliament which allowed mothers, against whom adultery had not been proved, to have the custody of children under seven, with rights of access to older children. "He was driven to do this by some personal experiences of his own, for in the course of his professional career he had twice been counsel for husbands resisting the claims of their wives, and had both times won his case in accordance with law and in violation of his sense of justice." (162)

Talfourd told Caroline about the case of Mrs Greenhill, "a young woman of irreproachable virtue". A mother of three daughters aged two to six, she found out her husband was living in adultery with another woman. She applied to the Ecclesiastical Court for a divorce. At the courts of King's Bench it was decided that she wife must not only deliver up the children, but that the husband had a right to debar the wife of all access to them. The Vice-Chancellor said that "however bad and immoral Mr Greenhill's conduct might be... the Court of Chancery had no authority to interfere with the common law right of the father, and no power to order that Mrs. Greenhill should even see her children". (163)

Talfourd highlighted the Greenhill case in the debate that took place over his proposed legislation. The bill was passed in the House of Commons in May 1838 by 91 to 17 votes (a very small attendance in a house of 656 members). Lord Thomas Denman, who was also the judge in the Greenhill case, made a passionate speech in favour of the bill in the House of Lords. Denman argued: "In the case of King v Greenhill, which was decided in 1836 before myself and the rest of the judges of the Court of the King's Bench, I believe there was not one judge who did not feel ashamed of the state of the law, and that it was such as to render it odious in the eyes of the country." (164)

Despite this speech the House of Lords rejected the bill by two votes. Very few members bothered to attend the debate that took place in the early hours of the morning. Caroline Norton remarked bitterly: "You cannot get Peers to sit up to three in the morning listening to the wrongs of separated wives." (165)

Talfourd was disgusted by the vote and published this response: "Because nature and reason point out the mother as the proper guardian of her infant child, and to enable a profligate, tyrannical, or irritated husband to deny her, at his sole and uncontrolled caprice, all access to her children, seems to me contrary to justice, revolting to humanity, and destructive of those maternal and filial affections which are among the best and surest cements of society." (166)

Caroline Norton now wrote another pamphlet, A Plain Letter to the Lord Chancellor on the Law of Custody of Infants. A copy was sent to every member of Parliament and in 1839 Talfourd tried again. The opponents of the proposed legislation spread rumours that Talfourd and Caroline "were lovers and that he had only became involved with the issue because of their sexual intimacy". (167)