On this day on 24th December

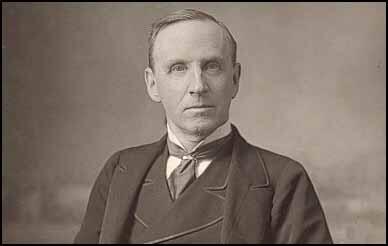

On this day in 1838 John Morley, the son of a doctor, was born in Blackburn. His father, Jonathan Morley, sent John to Lincoln College, Oxford, with the belief that he intended to become a clergyman. When John changed his mind, his father refused to support him financially and he had to leave university.

Morley decided to become a journalist and managed to find work with the Saturday Review. A follower of John Stuart Mill, Morley found the journal too conservative and in 1866 was offered the post of editor of the Fortnightly Review. Morley published the work of writers of different opinions, but his own articles, revealled him to be an advanced liberal. This included support for universal suffrage and a national education system. Morley was also an agnostic and upset most of his religious readers by spelling God with a small "g".

Morley made several times to enter the House of Commons. This included failures at Preston (1867), Blackburn (1869) and the London seat of Westminster (1880). In May 1880 he was appointed editor of the crusading newspaper, the Pall Mall Gazette. As editor Morley gave staunch support to William Gladstone and his government that had come to power following the 1880 General Election. As well as parliamentary reform, Morley was a staunch supporter of Irish Home Rule. With the help of two political allies, Joseph Chamberlain and Charles Dilke, Morley was given the safe Liberal seat of Newcastle.

After being elected to the House of Commons in 1883, Morley handed over the editorship of the Pall Mall Gazette to his able deputy, William Stead. However, he continued to edit the journal, Macmillans's Magazine, until being appointed by William Gladstone as Irish Secretary in 1885. A post he held until Gladstone was replaced as Prime Minister by the Marquess of Salisbury.

When William Gladstone became Prime Minister in 1892, he again appointed Morley as his Irish Secretary. However, attempts to persuade Parliament to accept Irish Home Rule ended in failure. In 1899 Morley re-established his credentials as a radical when he became one of the leading opponents of the Boer War.

Morley returned to the government when Henry Cambell-Bannerman became Prime Minister in 1905. He served as Secretary for India under Cambell-Bannerman and his successor, Herbert Asquith. In 1908 Morley was raised to the peerage and as Lord President of the Council played an important role in the reform of the House of Lords. It was Viscount Morley's speech threatening to create as many new peers as was necessary, that finally persuaded the Lords to back-down in its conflict with Asquith's Liberal Government.

John Morley was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War and along with Charles Trevelyan and John Burns, resigned from the government. The Daily News reported: "Whether men approve of that action (resigning) or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates. We could have wished that the long and honourable public career of Lord Morley had closed in peace. He has played a great and ennobling role in our national life and in losing him we lose a moral force that we can ill spare. He has brought distinction alike to literature and politics and wherever he has moved he has left the impress of an elevated purpose and unsullied character."

In September 1915, Morley's attempts to persuade the Liberal government to accept a negotiated peace with Germany ended in failure. Morley wrote several biographies in his lifetime including Edmund Burke (1867), Voltaire (1872), Rousseau (1876), Richard Cobden (1881) and William Gladstone (1903). John Morley died on 23rd September 1923.

On this day in 1865 Maud Robison, the daughter of a bank manager, was born on 24th December 1865 at Mudgee, New South Wales, the third of ten children of William Smoult Robison, a bank manager. The family moved to New Zealand when Maud was a child.

Sally Alexander described her as "tall and striking, with a handsome face, full red lips, dark eyes, and brown hair". She met her husband, William Pember Reeves (1857–1932), a journalist and politician eight years her senior, when she was nineteen. They married at Christchurch on 10th February 1885.

Maud's first child, William, lived only a few hours. Her second child, Amber Reeves, was born in 1887. After the birth of her second daughter, Beryl, in 1889, Maud took the first part of a BA in French, mathematics, and English at Canterbury College. Maud's studies were abandoned so that she could concentrate on the struggle for women's suffrage. In September 1893 New Zealand was the first country in the world to grant women the vote, and Maud chaired the first public meeting of enfranchised women in Christchurch soon afterwards.

In March 1896 William Reeves was appointed New Zealand agent-general in London. On their arrival in England they joined the Fabian Society and became friends with Hubert Bland, Edith Nesbit, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells. Maud also became active in the women's suffrage movement and in 1906 she was appointed to the executive of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. In 1908 she helped establish the Fabian Women's Group.

In 1909 Pember Reeves, Ethel Bentham and the Fabian Women's Group began a four year study of the daily lives of working-class families in Lambeth. Maud's biographer, Sally Alexander, has argued: "The Lambeth mothers' project, initiated by Maud, was prompted by the recognition that more infants died in the London slums than in Kensington or Hampstead... Forty-two families were selected from a lying-in hospital in Lambeth, London, to have weekly visits, medical examinations from Dr Ethel Bentham every two weeks, and 5s. to be paid to the mother for extra nourishment for three months before the birth of the baby and for one year afterwards. The money came from private donations, and the mothers wrote down their weekly expenditure. Eight families withdrew because the husbands objected to this weekly scrutiny. Eight other mothers who could not read or write dictated their sums to their husbands or children."

The report, written by Pember Reeves, was published as a Fabian pamphlet, Family Life on a Pound a Week in 1912. The material later appeared as a book Round About a Pound a Week. In the report, Pember Reeves argued for a series of government reforms including child benefit, free health clinics and the provision of school meals. She wrote: "If people living on £1 a week had lively imaginations, their lives, and perhaps the face of England, would be different."

During the First World War, Pember Reeves worked as Director of the Education and Propaganda Department of the Ministry of Food. Her son Fabian was killed while serving in the trenches in June, 1917. She was devastated by this news and she withdrew from public life.

Maud Pember Reeves died in a nursing home at 27 Powis Gardens, Golders Green, on 13th September 1953.

On this day in 1894 Frances Buss died. Frances, the daughter of Robert Buss and Frances Fleetwood was born on 16th August 1827. Robert Buss was an engraver but he was fairly unsuccessful and the family were extremely poor. Frances was the eldest of ten children, but only five of them survived beyond childhood.

Frances attended a local free school. Frances Buss did very well with her studies and at the age of fourteen she was asked to help teach the other children. Inspired by her daughter's educational achievements, Mrs. Buss decided to open her own school and Frances was given the job of teaching the older children. Frances had a strong desire to improve the standard of her teaching and in 1849 she became an evening student at the recently established Queen's College.

Inspired by her training, Buss decided to start her own school and in 1850 she established the North London Collegiate School for Girls. In an attempt to achieve and maintain high standards, Buss only employed qualified teachers. She also made use of visiting lecturers from Queen's College.

The North London Collegiate School soon developed a reputation for providing an excellent education for its students. Other women involved in the campaign to improve the education of women visited the school. This included Emily Davies who was to persuade the authorities to allow women to become students at London University. The two women became close friends and became involved in the campaign to secure the admission of girls to the Oxford and Cambridge examinations. In 1864 the Schools Enquiry Commission agreed to look into gender inequalities in education. In 1865 Frances Buss gave evidence to the commission.

In 1865 Frances Buss joined with Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Helen Taylor and Dorothea Beale to form a woman's discussion group called the Kensington Society. The following year the group formed the London Suffrage Committee and began organizing a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

Buss remained a strong supporter of universal suffrage. She also worked closely with Josephine Butler and helped her with campaigns against the white slave trade and the Contagious Diseases Act.

In 1871 Frances took the decision to change her North London Collegiate School from a private school to an endowed grammar school. Although this resulted in a loss of income, Buss was now able to offer a good education for those girls whose families could not afford the fees of a private school.

In 1880 Frances Buss began to suffer from a debilitating kidney disease, although she continued running the North London Collegiate School until her death on 24th December 1894.

On this day in 1907 Isador Feinstein Stone was born in Philadelphia. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia who owned a store in Haddonfield, New Jersey. He studied philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania and while a student he wrote for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

After leaving university he joined the Camden Courier-Post. Influenced by the work of Jack London, Stone became a committed radical journalist. A member of the Socialist Party of America, Stone campaigned for Norman Thomas in 1928.

In the 1930s he played an active role in the Popular Front opposition to Adolf Hitler. Stone moved to the New York Post in 1933 and during this period supported Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. His first book, The Court Disposes (1937), was a defence of Roosevelt's attempt to expand the Supreme Court.

After leaving the New York Post in 1939, Stone became associate editor of The Nation. Stone also became the Washington correspondent of the PM newspaper. It first began publishing on 18th June, 1940. The newspaper accepted no advertising in an attempt to be free of pressure from business interests. It relied on the financial backing of Marshall Field III. In its first editorial, that appeared on the front page, Ralph Ingersoll, the editor, wrote: "We are against people who push other people around" and demanded support for the Allies in the Second World War.

On 14th March, 1942, Stone attacked Martin Dies the chairman of House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in an article in PM: "It is a pity that Hitler's Reich does not have a Martin Dies. A special Committee of the Reichstag to harass Nazi officials and spread suspicion of Germany's allies could be forgiven the occasional exposure some notorious democrat. On a purely reciprocal basis the Reich might well go in for a Dies committee of its own in exchange for the growing readiness of our Congress to adopt innovations from Berlin."

Stone also pleaded with President Roosevelt to give more help to the Jews in Europe. On 10th June, 1944, he wrote: "I have been over a mass of material, some of it confidential, dealing with the plight of the fast-disappearing Jews of Europe and with the fate of suggestions for aiding them, and it is a dreadful story... I need not dwell upon the authenticated horrors of the Nazi internment camps and death chambers for Jews. That is not tragic but a kind of insane horror. It is our part in this which is tragic. The essence of tragedy is not the doing of evil by evil men but the doing of evil by good men, out of weakness, indecision, sloth, inability to act in accordance with what they knew to be right.... And the longer we delay the fewer Jews there will be left to rescue, the slimmer the chances to get them out. Between 4,000,000 and 5,000,000 European Jews have been killed since August 1942, when the Nazi extermination campaign began."

Stone next book was, Business as Unusual (1941), an attack on the country's failure to prepare for war. Underground to Palestine (1946) dealt with the migration of Eastern European Jews at the end of the Second World War. In 1948 Stone joined the New York Star. Later he moved to the Daily Compass until it ceased publication in 1952. A critic of the emerging Cold War, Stone published the Hidden History of the Korean War (1952).

Inspired by the achievements of George Seldes and his political weekly, In Fact, Stone started his own political paper, the I. F. Stone's Weekly in 1953. Over the next few years Stone led the attack on McCarthyism and racial discrimination in the United States. Stone remarked: "There was nothing to the left of me but The Daily Worker." Arthur Miller later recalled: "Apart from I.F. Stone, whose four-page self-published weekly newsletter persistently examined the issues without obeying the rule that every question had to be couched in anti-Communist declarations, there was no other journalist I can now recall who stood up ro the high wind without trembling.. With the tiniest Communist Party in the world the U.S. was behaving as though on the verge of bloody revolution."

Stone was a passionate supporter of the idea that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone gunman who killed President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on 22nd November, 1963. In the first issue after the assassination Stone wrote: "It is always dangerous to draw rational inferences from the behavior of a psychopath like Oswald."

On the publication of the Warren Commission Report Stone defended it in the I. F. Stone's Weekly, stating that "I believe the Commission has done a first-rate job, on a level that does our country proud and is worthy of so tragic an event. I regard the case against Lee Harvey Oswald as the lone killer of the President as conclusive." However, as John Kelin has pointed out in his book, Praise from a Future Generation, at the time Stone wrote this article: "the Warren Report had just been published and the twenty-six volumes of supporting evidence and testimony were still not available".

Stone then went on to criticise those who had argued that there had been a conspiracy. After attacking the work of Mark Lane he turned on Bertrand Russell, who he described as "my dear and revered friend". He suggested that Russell had dismissed the conclusions of Warren Commission report without even reading it. This was completely untrue. As Russell's assistant, Ralph Schoenman, later pointed out, he had been provided a copy of the report a week before its official release date.

Stone then went onto to look at the role played by Thomas G. Buchanan, Joachim Joesten and Carl Marzani, in the two books that had already been published arguing that there had been a conspiracy: "The Joesten book is rubbish, and Carl Marzani - whom I defended against loose charges in the worst days of the witch hunt - ought to have had more sense of public responsibility than to publish it. Thomas G. Buchanan, another victim of witch hunt days, has gone in for similar rubbish in his book, Who Killed Kennedy? You couldn't convict a chicken thief on the flimsy slap-together of surmise, half-fact and whole untruth in either book… All my adult life as a newspaperman I have been fighting, in defense of the Left and of a sane politics, against conspiracy theories of history, character assassination, guilt by association and demonology. Now I see elements of the Left using these same tactics in the controversy over the Kennedy assassination and the Warren Commission Report."

Ray Marcus, who was a devoted follower of I.F. Stone had had subscribed to his journal since its first edition in January 1953, was deeply shocked by this article. Marcus later recalled: "What was totally lacking in I. F. Stone's comments was any evidence of the critical analysis he normally employed on assessing official statements." On 8th October, 1964, Marcus wrote Stone a long letter outlining the flaws in the Warren Commission Report. Marcus argued that in order to accept the Warren Commission's lone-gunman scenario, one must accept fifteen points as true. These points were explained in an eight page letter. Marcus never received a reply.

In 1964 Stone was the first American journalist to challenge the account provided by President Lyndon B. Johnson of the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Throughout the 1960s Stone exposed the futility of the Vietnam War. The I. F. Stone's Weekly had a circulation of 70,000 but ill-health forced Stone to cease publication in 1971. However, Isador Feinstein Stone continued to write about politics until his death on 17th July, 1989.

On this day in 1914 there was a spontaneous outburst of hostility towards the killing on the Western Front. Arrangements were made between the two sides to go into No Mans Land to collect the dead. Negotiations also began to arrange a cease-fire for Christmas Day. Edward Hulse, a Lieutenant in the Scots Guards, received a message from the Germans suggesting a five day period without war.

Lieutenant Bruce Bairnsfather later recalled: "On Christmas morning I awoke very early and emerged from my dug-out into the trench. It was a perfect day. A beautiful, cloudless blue sky. The ground hard and white, fading off towards the wood in a thin low-lying mist.... Walking about the trench a little later... we suddenly became aware of the fact we were seeing a lot of evidences of Germans. Heads were bobbing about and showing over the parapet in a most reckless way, and, as we looked, this phenomenon became more and more pronounced.... A complete Boche figure suddenly appeared on the parapet, and looked about itself.... This was the signal for more Boche anatomy to be disclosed, and this was replied to by our men, until in less time than it takes to tell, half a dozen or so of each of the belligerents were outside their trenches and were advancing towards each other in no-man's land. I clambered up and over our parapet, and moved out across the field to look. Clad in a muddy suit of khaki and wearing a sheepskin coat and Balaclava helmet, I joined the throng about half-way across to the German trenches."

Later that day Second Lieutenant Dougan Chater wrote to his mother: "I think I have seen one of the most extraordinary sights today that anyone has ever seen. About 10 o'clock this morning I was peeping over the parapet when I saw a German, waving his arms, and presently two of them got out of their trenches and some came towards ours. We were just going to fire on them when we saw they had no rifles so one of our men went out to meet them and in about two minutes the ground between the two lines of trenches was swarming with men and officers of both sides, shaking hands and wishing each other a happy Christmas."

Another officer serving on the Western Front remarked that a "German climbed out of his trench and came over towards us. My friend and I walked out towards him. We met, and very gravely saluted each other. He was joined by more Germans, and some of the Dublin Fusiliers from our own trenches came out to join us. No German officer came out, it was only the ordinary soldiers. We talked, mainly in French, because my German was not very good, and none of the Germans could speak English well, but we managed to get together all right." One of the German soldiers said, "We don't want to kill you, and you don't want to kill us. So why shoot?"

On other parts of the front-line, German soldiers initiated a cease-fire through song. On Christmas Day the guns were silent and there were several examples of soldiers leaving their trenches and exchanging gifts in No Mans Land. The men even played a game of football.

Some historians have suggested that it was a myth that the Allies and the Germans played in a football match in No Mans Land during the Christmas Truce in 1914. Mark Connelly, Professor of Modern British History at the Center for War, Propaganda and Society at the University of Kent has been quoted as saying that "the entire episode has been romanticized in the intervening years." He says "there is no absolute hard, verifiable evidence of a match" taking place and says "the event has been glorified beyond recognition". (1)

It is true that an account that appeared in The Times on 1st January 1915 about a football match won 3-2 by the Germans is inaccurate. Researchers have discovered that the units named in the report “were separated not only by geographical distance but also by the river Lys."

However, there is evidence from other sources that a football match did take place. For example, Company-Sergeant Major Frank Naden of the 6th Cheshire Territorials, told The Newcastle Evening Mail: “On Christmas Day one of the Germans came out of the trenches and held his hands up. Our fellows immediately got out of theirs, and we met in the middle, and for the rest of the day we fraternised, exchanging food, cigarettes and souvenirs. The Germans gave us some of their sausages, and we gave them some of our stuff. The Scotsmen started the bagpipes and we had a rare old jollification, which included football in which the Germans took part. The Germans expressed themselves as being tired of the war and wished it was over. They greatly admired our equipment and wanted to exchange jack knives and other articles. Next day we got an order that all communication and friendly intercourse with the enemy must cease but we did not fire at all that day, and the Germans did not fire at us.”

In 1983, Ernie Williams, who was a 19 year old serving in the 6th Cheshires appeared on television to tell his story of the football match on the Western Front at Wulverghem: “The ball appeared from somewhere, I don't know where, but it came from their side - it wasn't from our side that the ball came. They made up some goals and one fellow went in goal and then it was just a general kickabout. I should think there were about a couple of hundred taking part. I had a go at the ball. I was pretty good then, at 19. Everybody seemed to be enjoying themselves. There was no sort of ill-will between us. There was no referee, and no score, no tally at all. It was simply a melee - nothing like the soccer you see on television. The boots we wore were a menace - those great big boots we had on - and in those days the balls were made of leather and they soon got very soggy.”

J. A. Farrell, was reported in The Bolton Chronicle as saying: “In the afternoon there was a football match played beyond the trenches, right in full view of the enemy.” According to The Guardian newspaper, the "German and British soldiers who famously played football with each other in no man's land on Christmas Day 1914 didn't always have a ball. Instead, they improvised. On certain sections of the front, soldiers kicked around a lump of straw tied together with string, or even an empty jam box."

We also have a German account of a football match. Lieutenant Gustav Riebensahm, of the 2nd Westphalian Regiment, wrote in his diary: “The English are extraordinarily grateful for the ceasefire, so they can play football again. But the whole thing has become slowly ridiculous and must be stopped. I will tell the men that from this evening it's all over.”

Despite this cease-fire on the Western Front 149 British servicemen died on Christmas Day 1914. Sir John French, the Commander of the British Expeditionary Force, reported that when he heard about the fraternization, "I issued immediate orders to prevent any recurrence of such conduct, and called the local commanders to strict account, which resulted in a great deal of trouble."

On this day in 1918 radical journalist Benjamin Flower died. Flower was born in Albion, Illinois on 19th October, 1858. After attending the University of Kentucky he found work as a journalist and by 1880 was editor of the American Sentinel.

In 1889 Flower founded The Arena, an American literary and political magazine. Flower left the journal in 1896 but returned in 1904 determined to make it "one of the great conscience forces in the English-speaking world." He added, "let us agitate, educate, organize and move forward, casting aside timidity and insisting that the Republic shall no longer lag behind in the march of progress."

W. T. Stead, the English investigative reporter, argued: "If we may judge of the editor from the magazine he edits, we should say that Mr. Flower is a young man with strong sympathies for the people, whose humanitarian instincts have not yet crystallized. He has great sympathies with socialism, especially in its protests against the slavery of women, but he recoils against any system which destroys liberty and cripples individualism."

Flower employed investigative journalist to obtain information that was part of his campaign for social, economic and political reform. In doing so, The Arena followed the example of McClure's Magazine and began to specialize in what became known as muckraking journalism. He later wrote: "The Arena (in the 1890s) was one of the fourmost magazines that was fearlessly waging a warfare on the unwarranted aggressions and corrupting influence of privileged wealth. The Arena appealed to thought-moulders. It had an enormous circulation among the clergy, to whom special rates had been granted because of the desire of the management that it should become pre-eminently a public educator, and it was felt that by reaching the public opinion-forming agencies we could in many instances start new centres for the diffusion of the light of justice, fundamental democracy, for intellectual hospitality."

After the closure of The Arena in 1909, Flower moved to Boston where he founded the Twentieth Century Magazine (1909-1913) and wrote Progressive Men, Women and Movements (1914).