Bruce Bairnsfather

Bruce Bairnsfather, the son of Thomas Bairnsfather and Amelia Every, was born in Muree, on 9th July 1888. Bruce's father was a Lieutenant in the Bengal Infantry. He attended schools in India and Stratford-upon-Avon. While taking evening classes in art he sold his first drawing (an advertisement for Player's Navy Mixture) at the age of 17 for two guineas.

Bairnsfather joined the British Army but he found army life boring and left the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and enrolled as an art student at the Hassall School of Art. After completing his training he produced advertising posters for products such as Lipton Tea, Players's Tobacco, Beechams and Flowers Beer.

On the outbreak of the First World War Bairnsfather rejoined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and within a couple of weeks had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant. After the Battle of Mons the British Army was desperately short of trained soldiers and Bairnsfather was quickly rushed to the Western Front where he served with people such as Captain Bernard Montgomery and Lieutenant A. A. Milne.

Bairnsfather, who was put in charge of a Maxim Machine-Gun section. He later recalled: "An extraordinary sensation - the first time of going into trenches.... It was a long and weary night, that first one of mine in the trenches. Everything was strange and wet and horrid. First of all I had had to go and fix up my machine guns at various points, and find places for the gunners to sleep in. This was no easy matter, as many of the dug-outs had fallen in and floated off down stream." Bairnsfather was so shocked by trench-life that he refused to take leave, fearing that once he left, he would find it too difficult to return. During the Christmas of 1914, Bairnsfather came close to being court-martialed after joining German soldiers in what later became known as the Christmas Truce.

While on the Western Front, Bairnsfather drew pictures of trench life and in 1915 The Bystander magazine began publishing his drawings. Bairnsfather's work was extremely popular with the soldiers in the trenches and this helped sales of the magazine. However, some people objected to his drawings and one member of the House of Commons condemned "these vulgar caricatures of our heroes."

In April 1915, Bairnsfather took part in the 2nd Battle of Ypres. After enduring a chlorine gas attack, Bairnsfather was badly wounded by a shell explosion. He was taken back to England and at London General Hospital his doctors diagnosed him as suffering from shellshock. While in hospital, The Bystander commissioned him to do a weekly drawing for the magazine. Later Bairnsfather's drawings were published in a series of books entitled, Fragments From France. A book that sold over 250,000 copies. He also published two books on his war experiences, Bullets & Billets (1916) and From Mud to Mufti (1919).

Instead of being sent back to the Western Front, Captain Bairnsfather was given the task of training new recruits at the Albany Barracks on the Isle of Wight. It was during this period that Bairnsfather created his famous cartoon character, Old Bill. Some people believe the character was based on his commanding officer in France, Sir Herbert Plumer, others claimed the inspiration came from Sydney Godley, the first private to win the Victoria Cross in the First World War. Later, Godley played the role of Old Bill to raise funds for the Royal British Legion Poppy Appeal.

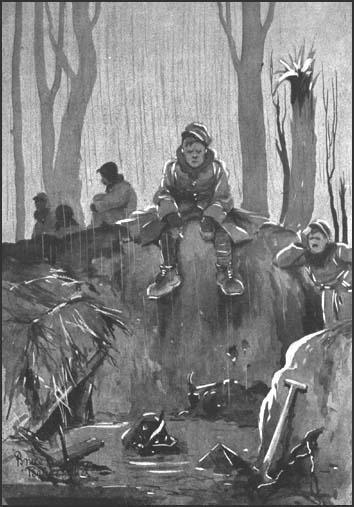

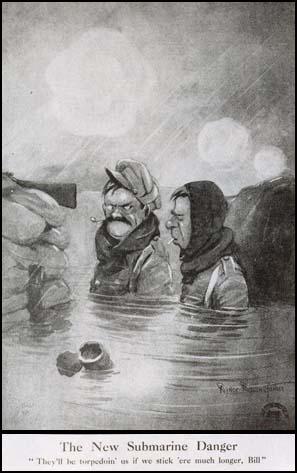

Bairnsfather's cartoons were extremely popular with soldiers in the trenches. As Martin Walker has pointed out, cartoons like A Hopeless Dawn (1916) and The New Submarine Danger (1917) were "the nearest thing to anti-war propaganda which the British media had to offer during the war." Walker goes onto argue in his book, Daily Sketches: A Cartoon History of Twentieth Century Britain (1978): "The cartoons were by a man who had fought in the trenches and who knew what that kind of wholly new warfare was like. Veterans of the Western Front have paid almost universal testimony to Bairnsfather as a historian of the conditions in which they fought and the sense of humour which the soldiers brought to bear against the life, or more precisely, against the death."

Mark Bryant has pointed out: "Old Bill appeared in books, plays, musicals, two feature films and comic strips. In addition he was reproduced on pottery, playing cards, jigsaw puzzles, postcards and other merchandise. An Old Bill waxwork was produced by Madame Tussaud's and a bus named after him now resides in the Imperial War Museum."

In the 1920s and 1930s several plays and films were produced featuring Bairnsfather's Old Bill character. Other books written and drawn by Bairnsfather during this period included Carry on Sergeant! (1927), Laughing Through the Orient(1933), Old Bill Looks at Europe (1935) and Old Bill Stands By (1939).

During the Second World War Captain Bairnsfather was appointed as an official cartoonist to the American Forces in Europe. This included contributing drawings for the American Forces newspaper, Stars and Stripes.

Bruce Bairnsfather died of acute renal failure after treatment for cancer of the bladder in Worcester Royal Infirmary on 29th September 1959.

Primary Sources

(1) Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets (1916)

An extraordinary sensation - the first time of going into trenches. The first idea that struck me about them was their haphazard design. There was, no doubt, some very excellent reason for someone making those trenches as they were; but they really did strike me as curious when I first saw them.

It was a long and weary night, that first one of mine in the trenches. Everything was strange and wet and horrid. First of all I had had to go and fix up my machine guns at various points, and find places for the gunners to sleep in. This was no easy matter, as many of the dug-outs had fallen in and floated off down stream.

(2) Bruce Bairnsfather was put in charge of a machine-gun unit on the Western Front.

No one gets a better idea of the general lie of the position than a machine-gun officer. In those early, primitive days, when we had so few of each thing, we, of course, had few machine guns, and these had to be sprinkled about a position to the best possible advantage. The consequence was that people like myself had to cover a considerable amount of ground before our rambles in the dark each night were done.

One machine gun might be, say, in "Dead Man Farm"; another at the 'Barrier' near the cross roads; whilst another couple were just at some effective spot in a trench, or in a commanding position in a shattered farm or cottage behind the front line trenches.

(3) Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets (1916)

It was during this first time up in the trenches that I got a soldier servant. As I had arrived only just in time to go with the battalion to the trenches, the acquisition had to be made by a search in the mud. I found a fellow who hadn't been an officer's servant before, but he wanted to be. I liked the look of him; so feeling rather like Robinson Crusoe, when he booked up Friday, "I got me a man."

This fellow of mine did all my cooking, such as it was, and worked in conjunction with my friend, the platoon commander's servant. Cooking, at the times I write about, consisted of making innumerable brews of tea, and opening tins of bully and Maconochie. Occasionally bacon had to be fried in a mess-tin lid. One day my man soared off into culinary fancies and curried a Maconochie. I have never quite forgiven him for this; I am nearly right now.

Soldier servants never had to leave the trench. It was their job to try and find something to make a fire with, and to do all they could to keep the water out of the dug-out, a task which not one of us succeeded in doing.

(4) Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets (1916)

Dug-outs had no wooden linings in those days; no corrugated iron roofs; no floorboards. They were just holes in the clay side of the fire trench, with any old thing for a roof, and old straw or tobacco leaves, which we pinched from some abandoned farm, for a floor.

(5) On 24th and 25th December, Bruce Bairnsfather took part in what became known as the Christmas Truce.

A voice in the darkness shouted in English, with a strong German accent, "Come over here!" A ripple of mirth swept along our trench, followed by a rude outburst of mouth organs and laughter. Presently, in a lull, one of our sergeants repeated the request, "Come over here!"

"You come half-way - I come half-way," floated out of the darkness.

"Come on, then!" shouted the sergeant. "I'm coming along the hedge!"

After much suspicious shouting and jocular derision from both sides, our sergeant went along the hedge which ran at right-angles to the two lines of trenches.

Presently, the sergeant returned. He had with him a few German cigars and cigarettes which he had exchanged for a couple of Machonochie's and a tin of Capstan, which he had taken with him.

On Christmas morning I awoke very early and emerged from my dug-out into the trench. It was a perfect day. A beautiful, cloudless blue sky. The ground hard and white, fading off towards the wood in a thin low-lying mist.

"Fancy all this hate, war, and discomfort on a day like this! I thought to myself. The whole spirit of Christmas seemed to be there, so much so that I remember thinking, "This indescribable something in the air, this Peace and Goodwill feeling, surely will have some effect on the situation here to-day!"

Walking about the trench a little later, discussing the curious affair of the night before, we suddenly became aware of the fact we were seeing a lot of evidences of Germans. Heads were bobbing about and showing over the parapet in a most reckless way, and, as we looked, this phenomenon became more and more pronounced.

A complete Boche figure suddenly appeared on the parapet, and looked about itself. This complaint became infectious. It didn't take "Our Bert" (the British sergeant who exchanged goods with the Germans the previous day) long to be up on the skyline. This was the signal for more Boche anatomy to be disclosed, and this was replied to by our men, until in less time than it takes to tell, half a dozen or so of each of the belligerents were outside their trenches and were advancing towards each other in no-man's land.

I clambered up and over our parapet, and moved out across the field to look. Clad in a muddy suit of khaki and wearing a sheepskin coat and Balaclava helmet, I joined the throng about half-way across to the German trenches.

This was my first real sight of them at close quarters. Here they were - the actual practical soldiers of the German army. There was not an atom of hate on either side that day; and yet, on our side, not for a moment was the will to beat them relaxed. It was just like the interval between the rounds in a friendly boxing match.

The difference in type between our men and theirs was very marked. There was no contrasting the spirit of the two parties. Our men, in their scratch costumes of dirty, muddy khaki, with their various assorted head-dresses of woollen helmets, mufflers and battered hats, were a light-hearted, open, humourous collection as opposed to the sombre demeanour and stolid appearance of the Huns in their grey-green faded uniforms, top boots, and pork-pie hats.

These devils, I could see, all wanted to be friendly; but none of them possessed the open, frank geniality of our men. However, everyone was talking and laughing, and souvenir hunting. Suddenly, one of the Boches ran back to the trench and presently reappeared with a large camera. I posed in a mixed group for several photographs, and I have ever since wished I had fixed up some arrangement for getting a copy.

(6) Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets & Billets (1916)

It was quite the worse trench I have ever seen. A number of men were in it, standing and leaning, silently enduring the following conditions. It was quite dark. The enemy were about two hundred yards away, or rather less. It was raining, and the trench contained over three feet of water. The men, therefore, were standing up to the waist in water. The front parapet was nothing but a rough earth mound which, owing to the water about, was practically non-existent. They were all wet through and through, with a great deal of their equipment below the water at the bottom of the trench. There they were, taking it all as a necessary part of a great game; not a grumble nor a comment.

(7) In April 1915, Bruce Bairnsfather took part in the offensive at Ypres.

Now we were in it! Bullets were flying through the air in all directions. A few men had gone down already, and no wonder - the air was thick with bullets. In front of me an officer was hurrying along when I saw him throw up his hands and collapse on the ground. I hurried across to him, and lifted his head on to my knee. He couldn't speak and was rapidly turning a deathly pallor. I undid his equipment and the buttons of his tunic as fast as I could, to find out where he had been shot. Right through the chest. The left side of his shirt, near his heart, was stained deep with blood. He was a captain in the Canadians.

All movement in the attack had now ceased, but the rifle and shell fire was as strong as ever. I got hold of a subaltern and together we ran back with a stretcher to where I left the captain. We lifted him on the stretcher. He seemed a bit better, but his breathing was very difficult. How I managed to hold up that stretcher I don't know. I was just verging on complete exhaustion by this time. We got him in and put him down in an outbuilding which had been turned into a temporary dressing station.

I left him, and went across towards the farm. As I went I heard the enormous ponderous, gurgling, rotating sound of large shells coming. I looked to my left. Four columns of black smoke and earth shot up a hundred feet into the air, not eighty yards away. Then four mighty reverberating explosions that rent the air.

As I was on the sloping bank of the gully I heard a colossal rushing swish in the air, and then didn't hear the resultant crash. All seemed dull and foggy; a sort of silence, worse than all the shelling, surrounded me. I lay in a filthy stagnant ditch covered with mud and slime from head to foot. I suddenly started to tremble all over. I couldn't grasp where I was. I lay and trembled. I had been blown up by a shell.

I lay there some little time, I imagine, with a most peculiar sensation. All fear of shells and explosions had left me. I still heard them dropping about and exploding, but I listened to them and watched them as calmly as one would watch an apple fall off a tree. I could not make myself out. Was I right or wrong? I tried to get up, and then I knew. The spell was broken. I shook all over, and had to to lie still, with tears pouring down my face. I could see my part in the battle was over.