On this day on 18th October

On this day in 1775 African-American poet Phillis Wheatley is freed from slavery.

Phillis Wheatley was born in Senegal in about 1753. She was captured by slave traders and brought to America in 1761. Phillis was sold at a slave-market in Boston.

According to one source: "She was purchased by Mr. John Wheatley, a respectable citizen of Boston. This gentleman, at the time of the purchase, was already the owner of several slaves; but the females in his possession were getting something beyond the active periods of life, and Mrs. Wheatley wished to obtain a young negress, with the view of training her up under her own eye, that she might, by gentle usage, secure to herself a faithful domestic in her old age. She visited the slave-market, that she might make a personal selection from the group of unfortunates offered for sale. There she found several robust, healthy females, exhibited at the same time with Phillis, who was of a slender frame, and evidently suffering from change of climate. She was, however, the choice of the lady, who acknowledged herself influenced to this decision by the humble and modest demeanor and the interesting features of the little stranger."

Phillis apparently "gave indications of uncommon intelligence, and was frequently seen endeavoring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal." Phillis was taught to read by one of Wheatley's daughters. Phillis studied English, Latin and Greek and in 1767 began writing poetry. Her first poem, on the death of George Whitefield, was published in 1770. When Phillis was eighteen she travelled to London and while there the Countess of Huntingdon, helped her publish a collection of her work, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773).

After the death of John Wheatley and his wife, Phillis married John Peters, a free black man, who ran a small grocery store in Boston. "At this period of destitution, Phillis received an offer of marriage from a respectable colored man of Boston. The name of this individual was Peters. He kept a grocery in Court-Street, and was a man of very handsome person and manners; wore a wig, carried a cane, and quite acted out 'the gentleman.' In an evil hour he was accepted; and he proved utterly unworthy of the distinguished woman who honored him by her alliance. He was unsuccessful in business, and failed soon after their marriage; and he is said to have been both too proud and too indolent to apply himself to any occupation below his fancied dignity. Hence his unfortunate wife suffered much from this ill-omened union." The business was unsuccessful and Phillis was forced to find work as a servant.

Phillis Wheatley died in poverty in Boston on 5th December, 1784.

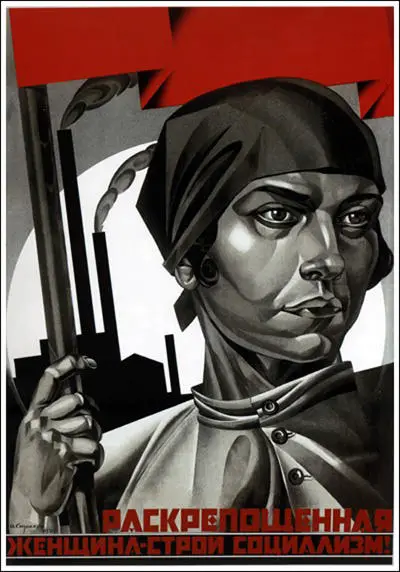

On this day in 1896 Soviet artist Adolf Strakhov was born in the town of Dnipropetrovsk. He graduated from Odessa Art School in 1915.

One of the founders of the Socialist Realist art movement he produced several paintings and posters dedicated to the events of the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War.

Strakhov's most famous work was "The Emancipated Woman is Building Socialism" (1926). However, as David King, the author of Red Star over Russia (2010) has pointed out: "Strakhov portrays the politicised woman factory worker as an integral part of the class struggle. Soviet communist policy, overwhelmingly decided by men, opposed the idea of an independent women's liberation movement."

Adolf Strakhov died in Kharkiv on 3rd January,1979.

On this day in 1831 anti-slavery campaigner Elizabeth Heyrick died and therefore did not live to see the passing of the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act.

Elizabeth Coltman was born in Leicester on 4th December 1769. Her father, John Coltman, was a successful worsted manufacturer. Her mother, Elizabeth Cartwright (1737–1811), was a published poet and book reviewer. John Wesley visited the family home in 1785.

Elizabeth, known as Bess when young, "was singular in her childhood" and it was said that when she gave her "pennies to a beggar and choosing for rescue a plain kitten in preference to a pretty one". Her talent for landscape painting gave her father "half a mind" to "make her artist" like Angelica Kauffman.

On 10th March 1787 Elizabeth married John Heyrick, a Methodist lawyer. Elizabeth Heyrick was still childless when her husband died of a heart-attack eight years later. According to her biographer: "The marriage was said to have been stormy, but she mourned fervently, with lifelong observance of the anniversary of his death. They had no children."

After the death of her husband Elizabeth Heyrick moved back into her parents home. Elizabeth, now a member of the Society of Friends, renounced all worldly pleasures and devoted herself to social reform. A follower of Tom Paine, she campaigned against bull-baiting and became a prison visitor. Elizabeth also wrote eighteen political pamphlets on a wide variety of subjects including, the Corn Laws. In one pamphlet she pointed out that a women was "especially qualified to plead for the oppressed."

Adam Hochschild has pointed out that Elizabeth Heyrick was a committed political reformer "She (Elizabeth Heyrick) stopped a bull-baiting contest by buying the bull and hiding it in the parlor of a nearby cottage until the angry crowd went away. To experience the life of Irish migrant workers, she lived in a shepherd's cottage eating only potatoes. She visited prisons and paid fines to get poachers released... She called for laws reforming prisons and limiting the workday; she supported a strike by weavers in her hometown of Leicester, even though her own brother was an employer in the industry."

Heyrick's main concern was the campaign against slavery. Her elder brother, Samuel Coltman, had been part of the original abolition movement in the 1790s. It is claimed that Elizabeth was influenced by the ideas of the Unitarian movement. "Many unitarians concluded that the only significant difference between women and men was men's capacity for physical force. There appeared no 'natural' reasons why women should not use their capacities for intellectual and moral growth to bring social progress, including the removal of slavery as an institution that stunted intellectual and moral growth."

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak at women's anti-slavery societies. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture".

However, George Stephen disagreed with Wilberforce on this issue and claimed that their energy was vital in the success of the movement: "Ladies Associations did everything... They circulated publications; they procured the money to publish; they talked, coaxed and lectured: they got up public meetings and filled our halls and platforms when the day arrived; they carried round petitions and enforced the duty of signing them... In a word they formed the cement of the whole anti-slavery building - without their aid we never should have kept standing."

Thomas Clarkson, another leader of the ant-slavery movement, was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions."

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society.

Elizabeth Heyrick was an early exponent of direct action and organised a sugar boycott in Leicester. She visited all the city's grocers to urge them to only stock goods that did not involve slavery. She pointed out: "The West Indian planter and the people of this country, stand in the same moral relation to each other, as the thief and the receiver of stolen goods... Why petition Parliament at all, to do that for us, which... we can do more speedily and more effectively for ourselves."

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). (16) The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). Eventually there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery.

Although virtually all the prominent male opponents of slavery were still talking about the freeing of the slaves over a thirty year period, Elizabeth Heyrick, severely criticised these men and demanded a different strategy. In the 1826 General Election she called for people to vote only for candidates who supported the freeing the slaves now. She quoted a letter that she had received from a woman in Wiltshire: "Men may propose only gradually to abolish the worst of crimes... but why should we countenance such enormities? We must not talk of gradually abolishing murder, licentiousness, cruelty, tyranny."

The Anti-Slavery society realised the importance of Elizabeth Heyrick's as a propagandist for the cause. Her writing had the ability to arouse public opinion. In 1828 they printed copies of her pamphlet, Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women. The main method of distribution was house-to-house canvassing, where publications were sold to the better-off or lent to the poor.

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition.

In her final years Elizabeth Heyrick grew very depressed about her lack of success to get slavery abolished. She wrote to Lucy Townsend: "Nothing human can dispel that despairing torpor into which I have been plunging deeper and deeper for many months past."

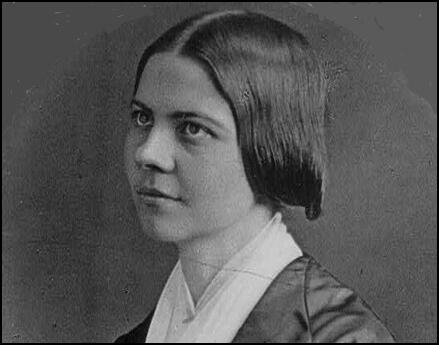

On this day in 1893 women's suffragist, Lucy Stone died in Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Lucy Stone was born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts on 13th August, 1818. At the age of sixteen she became a teacher but after saving enough funds she studied at Oberlin College.

After graduating in 1847, Stone worked as a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. As well as speaking about the evils of slavery, Stone also advocated woman's suffrage and was responsible for recruiting Susan B. Anthony and Julia Ward Howe to the movement.

In 1855 Stone married Henry B. Blackwell, a man also active in the anti-slavery movement. During the marriage service they pledge that both partners would have absolutely equal rights in marriage. In protest against the laws that discriminated against women, Stone retained her own name.

In 1869 Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Josephine Ruffin formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in Boston. Less militant that the National Woman Suffrage Association, the AWSA was only concerned with obtaining the vote and did not campaign on other issues.

Over the next twenty years Stone edited the Woman's Journal, a feminist weekly magazine, and wrote a large number of woman's suffrage leaflets.

Her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, edited the Woman's Journal for 35 years. Lucy's last words to her daughter were "make the world better".

On this day in 1900 Kaiser Wilhelm II appoints Count Bernhard von Bülow as chancellor of Germany. He adopted an aggressive foreign policy and upset France by his actions in Morocco in 1905. He also antagonized Russia in the Bosnian crisis in 1908. His foreign policy encouraged the formation of the Triple Entente.

In October 1908 Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph where he indiscreetly revealed his desire for a larger navy. Bülow, who approved the interview, was blamed for the arm's race that followed. Bülow held office until June 1909 when he was forced to resign after losing support in the Reichstag and was replaced by Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg.

Bülow served as ambassador to Italy (1914-15) and published a book on foreign policy, Imperial Germany.

Bernhard von Bülow died on 28th October 1929.

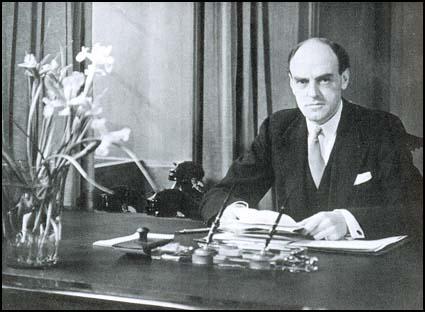

On this day in 1922 the British Broadcasting Company (later Corporation) is set up by a group of executives from radio manufacturers. In December 1922. John Reith became general manager of the organization.

In 1927 the government decided to establish the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a broadcasting monopoly operated by a board of governors and director general. The BBC was funded by a licence fee at a rate set by parliament. The fee was paid by all owners of radio sets. The BBC therefore became the world's first public-service broadcasting organization. Unlike in the United States, advertising on radio was banned.

John Reith was appointed director-general of the BBC. Reith had a mission to educate and improve the audience and under his leadership the BBC developed a reputation for serious programmes. Reith also insisted that all radio announcers wore dinner jackets while they were on the air. In the 1930s the BBC began to introduce more sport and light entertainment on the radio.

The BBC began the world's first regular television service in 1936. This service was halted during the Second World War and all BBC's efforts were concentrated on radio broadcasting. In 1940 John Reith was appointed as Minister of Information

Writers such as J. B. Priestley, George Orwell, T. S. Eliot, William Empson, and Charlotte Haldane were recruited by the BBC and radio was used for internal and external propaganda. This included broadcasting radio programmes to countries under the control of Nazi Germany. These radio programmes went out in 40 different languages

The BBC television service was resumed in 1946 and by the early 1950s it became the dominant part of its activities. Its broadcasting monopoly came to an end with the introduction of commercial television under the Independent Television Authority in 1954. This was followed by the introduction of commercial radio stations in 1972.

It has been claimed that BBC is the most universally recognizable set of initials in the world. For example, by the end of the 20th century an estimated 150 million people were listening to BBC World Service radio.

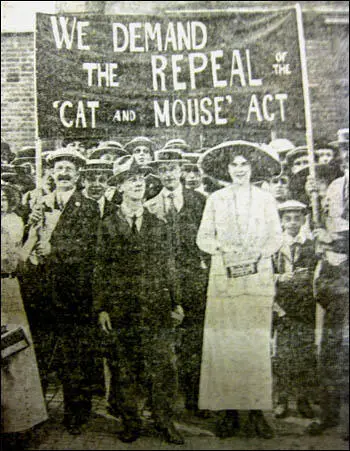

On this day in 1913 Miriam Pratt admits in court that she was guilty of setting fire to Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women, in Storey's Way, Cambridge, with paraffin-soaked cloth.

"I ask you to look again at what has been done and see in it not wilful and malicious damage, but a protest against a callous Government, indifferent to reasoned argument and the best interests of the country. A protest carried to extreme because no other means would avail... show by your verdict today that to fight in the cause of human freedom and human betterment is to do no wrong."

Miriam was sentenced to eighteen months' hard labour and sent to Holloway Prison. Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Miriam were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts.

On this day in 1939 Lee Harvey Oswald was born in New Orleans. His father, Robert Oswald, died two months before his son was born. At the age of three his mother, Marguerite Oswald, sent him to live in the Bethleham Children's Home.

Oswald went to live with his mother in Benbrook, Texas when she married Edwin Ekdahl. The marriage did not last and Marguerite Oswald took her three sons to a new home in Fort Worth. The two elder brothers, John and Robert, found work and in 1952 Marguerite and Lee moved to New York. Although considered an intelligent boy, Lee Harvey Oswald's behaviour at school deteriorated. He was sent to a detention centre and underwent psychiatric treatment.

In 1955 Oswald joined the Civil Air patrol where he served under David Ferrie. The following year Oswald became interested in politics. He read books written by Karl Marx and told friends that he was a Marxist. He also joined the Young People's Socialist League. He later told a friend that his involvement in politics dated back to reading a pamphlet about the execution of Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg.

Oswald left school at sixteen and the following year joined the U.S. Marines. After basic training Oswald qualified as an Aviation Electronics Operator and in 1957 was posted to the Atsugi Air Base in Japan. He soon got into trouble for being in possession of an unregistered weapon. In March 1958 he was found guilty of using "provoking words" in a quarrel with a sergeant.

Oswald also served in Taiwan and the Philippines before returning to his base in California. He remained interested in politics and became an outspoken supporter of Fidel Castro and his revolution in Cuba. In 1959 Oswald left the Marines. Soon afterwards he travelled to Finland. After a short stay in Helsinki he acquired a six day tourist visa to enter the Soviet Union. Oswald went to Moscow and applied to become a Soviet citizen.

On 13th November, 1959, Arline Mosby, who worked for United Press International (UPI) interviewed Oswald. Mosby later told a fellow journalist: "He (Oswald) struck me as being a rather mixed-up young man of not great intellectual capacity or training, and somebody that the Soviet Union wouldn't certainly be much interested in."

Three days later, Priscilla Johnson checked into the same hotel as Osward. The following day she visited the American Embassy to pick up her mail (16th November, 1959). According to Johnson, John McVickar approached her and told her that "there's a guy in your hotel who wants to defect, and he won't talk to any of us here". She later told the Warren Commission: "John McVickar said she was refusing to talk to journalists. So I thought that it might be an exclusive, for one thing, and he was right in my hotel, for another." As Johnson was leaving the American Embassy McVickar told her "to remember she was an American."

Lee Harvey Oswald agreed to be interviewed by Johnson. She later testified that they talked from between nine until one or two in the morning. Oswald told her: "Once having been assured by the Russians that I would not have to return to the United States, come what may, I assumed it would be safe for me to give my side of the story."

Johnson's article appeared in the Washington Evening Star. Surprisingly, the article did not include Oswald's threat to reveal radar secrets. Nor was it mentioned in any other article or book published by Johnson on Oswald. However, under oath before the Warren Commission she admitted that Oswald had told her that "he hoped his experience as a radar operator would make him more desirable to them (the Soviets)".

When Oswald's application to stay in the Soviet Union he was rejected Oswald attempted suicide by cutting his wrist. Oswald was kept in hospital for a week and after his release was allowed to remain in the country.

In January, 1960, Oswald was sent to Minsk where he was given work as an assembler at a radio and television factory. While there he met Marina Prusakova, a nineteen year old pharmacy worker, and in April 1960 the couple got married. Oswald soon got disillusioned with life in the Soviet Union and in June, 1962, he was given permission to take his wife and baby daughter to the United States.

The Oswald family settled in Fort Worth. Later the family lived in Dallas and New Orleans. He lived for a while with Charles Murret and his wife Lillian. Murret worked as a steamship clerk. He was also an illegal bookmaker and an associate of Sam Saia, one of the leaders of organized crime in New Orleans. Saia was also a close friend of Carlos Marcello.

Marina Oswald later claimed that on 10th April, 1963, Oswald attempted to assassinate General Edwin Walker, a right-wing political leader. She reported that she "asked him what happened, and he said that he just tried to shoot General Walker. I asked him who General Walker was. I mean how dare you to go and claim somebody's life, and he said "Well, what would you say if somebody got rid of Hitler at the right time? So if you don't know about General Walker, how can you speak up on his behalf?." Because he told me... he was something equal to what he called him a fascist."

In April, 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald moved to New Orleans. On 26th May, 1963, Oswald wrote to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and proposed "renting a small office at my own expense for the purpose of forming a FPCC branch here in New Orleans". Three days later, without waiting for a reply, Oswald ordered 1,000 copies of a handbill from a local printers. It read: "Hands Off Cuba! Join the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, New Orleans Charter Member Branch, Free Literature, Lectures, Everyone Welcome!"

According to Bill Simpich: "4/18/63 is the postmark date of the letter sent from Dallas by Oswald to the national FPCC office in New York. An FBI memo about this letter refers to “photographs of the below listed material made available by NY 3245-S* on 4/21/63...in the event any of this material is disseminated outside the bureau, caution should be exercised to protect the source, NY 3245-S*, and the communication should be classified “Confidential”". This refers to Victor Thomas Vicente, who was the FBI spy at the FPCC.

Oswald rented an office for the FPCC at 544 Camp Street. No one joined the FPCC in New Orleans but Oswald did send out two honourary membership cards to Gus Hall and Benjamin Davis, two senior members of the American Communist Party.

On 9th August, 1963, he was giving out his Fair Play for Cuba Committee leaflets when he became involved in a fight with Carlos Bringuier. Oswald was arrested and on 12th August, he was found guilty and fined $10. While in prison he was visited by FBI agent, John L. Quigley. Five days later Oswald debated the issue of Fidel Castro and Cuba with Bringuier and Ed Butler on the Bill Stuckey Radio Show. Later that month Oswald was seen in the company of David Ferrie and Clay Shaw.

In September, 1963, Marina Oswald moved to Dallas to have her second child. Lee Harvey Oswald visited Mexico City where he visited the Cuban Embassy where he attempted to get permission to travel to Cuba. His application was turned down and after trying to get a visa for the Soviet Union he arrived in Dallas in October, 1963. Marina and June were living with a woman called Ruth Paine. Oswald rented a room in Dallas and with the help of Paine, he found a job at the Texas School Book Depository.

On 22nd November, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Dallas. It was decided that Kennedy and his party, including his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John Connally and Senator Ralph Yarborough, would travel in a procession of cars through the business district of Dallas. A pilot car and several motorcycles rode ahead of the presidential limousine. As well as Kennedy the limousine included his wife, John Connally, his wife Nellie, Roy Kellerman, head of the Secret Service at the White House and the driver, William Greer. The next car carried eight Secret Service Agents. This was followed by a car containing Lyndon Johnson and Ralph Yarborough.

At about 12.30 p.m. the presidential limousine entered Elm Street. Soon afterwards shots rang out. John F. Kennedy was hit by bullets that hit him in the head and the left shoulder. Another bullet hit John Connally in the back. Ten seconds after the first shots had been fired the president's car accelerated off at high speed towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. Both men were carried into separate emergency rooms. Connally had wounds to his back, chest, wrist and thigh. Kennedy's injuries were far more serious. He had a massive wound to the head and at 1 p.m. he was declared dead.

Witnesses at the scene of the assassination claimed they had seen shots being fired from behind a wooden fence on the Grassy Knoll and from the Texas School Book Depository. The police investigated these claims and during a search of the TSBD they discovered on the floor by one of the sixth floor windows, three empty cartridge cases. They also found a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle hidden beneath some boxes.

Oswald was seen in the Texas School Book Depository before (11.55 a.m.) and just after (12.31 p.m.) the shooting of John F. Kennedy. At 12.33 Oswald was seen leaving the building and by 1.00 p.m arrived at his lodgings. His landlady, Earlene Roberts, testified before the Warren Commission that Oswald stayed only a few minutes but while he was in the house a Dallas Police Department car parked in front of the house. In the car were two uniformed policemen. Roberts described how the driver sounded the horn twice before driving off. Soon afterwards Oswald left the house.

At 1.16 p.m. J. D. Tippet, a Dallas policeman, approached a man, later identified as Oswald, walking along East 10th Street. A witness later testified that after a short conversation Oswald pulled out a hand gun and fired a number of shots at Tippet. Oswald ran off leaving the dying Tippet on the ground.

John Brewer was manager of Hardy's Shoe Store in Oak Cliff. After hearing a news flash that J. D. Tippit had been shot nearby, he saw a man acting strangely outside the shop: "The police cars were racing up and down Jefferson with their sirens blasting and it appeared to me that this guy was hiding from them. He waited until there was a break in the activity and then he headed west until he got to the Texas Theatre."

Brewer went into the theatre and spoke to Warren Burroughs, the assistant manager. Burroughs had seen him enter the balcony of the theatre. When the police arrived Brewer accompanied the officers into the cinema where he pointed out the man he had seen acting in a suspicious manner. After a brief struggle Oswald was arrested.

During his interrogation by the Dallas Police Oswald requested the services of John Abt. He is recorded as saying: "I want that attorney in New York, Mr. Abt. I don't know him personally but I know about a case that he handled some years ago, where he represented the people who had violated the Smith Act... I don't know him personally, but that is the attorney I want... If I can't get him, then I may get the American Civil Liberties Union to send me an attorney." However, Abt was on holiday in Connecticut and later told reporters that he had received no request either from Oswald or from anyone on his behalf to represent him.

The police soon found out that Oswald worked at the Texas School Book Depository. They also discovered his palm print on the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle that was found earlier that day. Other evidence emerged that suggested that Oswald had been involved in the killing of John F. Kennedy. Oswald's hand prints were found on the book cartons and the brown paper bag. Charles Givens, a fellow worker, testified that he saw Oswald on the sixth floor at 11.55 a.m. Another witness, Howard Brennan, claimed he saw Oswald holding a rifle at the sixth floor window.

The police also discovered that the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle was purchased under the name A. Hiddell. When he was arrested, the police found that Oswald was carrying a forged identity card bearing the name Alek Hiddell. The rifle had been sent by the mail order company from Chicago to P.O. Box 2915, Dallas, Texas. The Post Office box belonged to Oswald.

Lee Harvey Oswald was interrogated by the Dallas Police for over 13 hours. However, the police made no tapes nor took any transcripts of the interrogations. Oswald denied he had been involved in the killing of Kennedy. He also told newsmen on the night of the assassination he was a "patsy" (a term used by the Mafia to describe someone set up to take the punishment for a crime they did not commit).

On 24th November, 1963, Jesse Curry decided to transfer Oswald to the county jail. Will Fritz placed George Butler in immediate charge of the transfer. Ike Pappas, a journalist working for WNEW Radio in Maryland was one of the hundred people watching Oswald being led through the basement of police headquarters. “I noted out of the corner of my eye, this black streak went right across my front and leaned in and, pop, there was an explosion. And I felt the impact of the air from the explosion of the gun on my body.... And then I said to myself, if you never say anything ever again into a microphone, you must say it now. This is history.” The gunman was quickly arrested by police officers. Oswald died soon afterwards. The man who killed him was later identified as being Jack Ruby.

On this day in 1963 Sir Alec Douglas Home becomes prime minister. He immediately resigned his peerage and won a by-election at Kinross and Western Perthshire. A year later the Conservative Party was defeated at the 1964 General Election and Harold Wilson became the new prime minister.

On this day in 1973 suffrage campaigner Elsie Bowerman suffered a stroke, and died at the Princess Alice Hospital, Eastbourne..

Elsie Bowerman, the only child of William Bowerman (1825–1895) and his wife, Edith Martha Barber (1864–1953), was born in Tunbridge Wells on 18th December 1889. She was educated at Wycombe Abbey School (1901–7) before going to finishing school in Paris.

According to Helena Wojtczak: "Around 1907, the widowed Edith Bowerman, now 43, married 67-year-old Alfred Benjamin Chibnall, a wealthy farmer. This alliance remains mysterious. Hastings Rates books and street directories show no trace that the couple ever lived together."

In 1908 Elsie Bowerman went to Girton College. The following year Bowerman and her mother joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She established a branch in Girton and in October 1910 she invited Margery Corbett-Ashby to speak to the students. Later she arranged for Constance Lytton to speak at the college. She also sold copies of Votes for Women and gave away free copies to those who could not afford the.

On 22nd November, Elsie's mother, Edith Chibnall joined a WSPU deputation to the House of Commons. She was assaulted by a policeman. She explained in a letter to Elsie: "He caught me by the hair and flinging me aside he said, Die, then! I found afterwards that so much force had been used that my hairpins were bent double in my hair and my sealskin coat was torn to ribbons." Elsie replied: "So sorry you have had such a bad time. It is sickening that this endless fighting has to go on. I am frightfully sorry Mrs. Pankhurst & Mrs. Haverfield were arrested... It is a great pity to lose all our best people just before the Election. I hope you won't go on any more raids. I think you have done your share for this week."

In 1911 Bowerman graduated with a second-class degree in medieval and modern languages. She now moved to St Leonards where her mother had established a branch of the WSPU. Bowerman helped her mother run the WSPU shop on the Grand Parade at Hastings. Bowerman was also a paid full-time organizer for the organization.

Elsie Bowerman and her mother decided to take a holiday in the Ohio. On 15th April 1912 they were passengers on the Titanic when it sank. As they were both first-class passengers every effort was made to save them. Elsie later wrote: "The silence when the engines stopped was followed by a steward knocking on our door and telling us to go on deck. This we did and were lowered into life-boats, where we were told to get away from the liner as soon as we could in case of suction. This we did, and to pull an oar in the midst of the Atlantic in April with ice-bergs floating about, is a strange experience."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Bowerman supported the decision by Emmeline Pankhurst, to help Britain's war effort. In 1914 Eveline Haverfield founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Christabel Marshall described Haverfield as looking "every inch a soldier in her khaki uniform, in spite of the short skirt which she had to wear over her well-cut riding-breeches in public." Appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps, Haverfield was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia.

On 5th July, 1916, Elsie Bowerman wrote to her mother: "Mrs Haverfield has just asked me to go out to Serbia at the beginning of August, to drive a car - May I go? I know Miss Whitelaw would let me off Wycombe to go. It is what I've been dying to do & drive a car ever since the war started. I should have to spend the week after the procession learning to drive - the cars are Fords - if I went I would come home when I come back I would not have to go to W.A. It is really like a chance to go to the front. They want drivers so badly. So do say yes - It is too thrilling for words."

According to Elizabeth Crawford: "In September 1916 Elsie Bowerman sailed to Russia as an orderly with the Scottish women's hospital unit, at the request of the Hon. Evelina Haverfield, a fellow suffragette whom she had known for several years. With this unit she travelled via Archangel, Moscow, and Odessa to serve the Serbian and Russian armies in Romania. The women arrived as the allies were defeated, and were soon forced to join the retreat northwards to the Russian frontier."

While awaiting her passage home, in March 1917, Elsie Bowerman witnessed the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in St Petersburg. She wrote to her mother: "Throughout we have met with the utmost politeness & consideration from everyone. Revolutions carried out in such a peaceful manner really deserve to succeed. Today weapons only seem to be in the hands of responsible people - not as yesterday, carried in many cases by excited youths. Heard that the ministers have now surrendered. Some have been shot, or shot themselves."

In 1917 Elsie Bowerman became a member of the The Women's Party, an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." The party also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Christabel became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the post-war election. Christabel Pankhurst represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. Elsie Bowerman became her agent but despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, she lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party by 775 votes.

In 1922 Elsie Bowerman and Flora Drummond established the Women's Guild of Empire, a right wing league opposed to communism. Drummond's biographer, Krista Cowman, pointed out: "When the war ended she was one of the few former suffragettes who attempted to continue the popular, jingoistic campaigning which the WSPU had followed from 1914 to 1918. With Elsie Bowerman, another former suffragette, she founded the Women's Guild of Empire, an organization aimed at furthering a sense of patriotism in working-class women and defeating such socialist manifestations as strikes and lock-outs." By 1925 it was claimed the organization had a membership of 40,000. In April 1926, Bowerman and Drummond led a demonstration that demanded an end to the industrial unrest that was about to culminate in the General Strike.

Elsie Bowerman, a member of the Middle Temple, read for the bar, and became one of the first women barristers. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "She practised on the south-eastern circuit from 1928 until 1946, was involved with the Sussex sessions from 1928 until 1934, and wrote The Law of Child Protection (1933)."

In 1938, she joined forces with the Marchioness of Reading, to establish the Women's Voluntary Service, and from 1938 to 1940 edited its Monthly Bulletin. During the Second World War she worked for the Ministry of Information (1940–41) and was liaison officer with the North American Service of the BBC (1941–5).