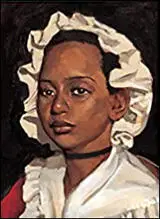

Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley was born in Senegal in about 1753. She was captured by slave traders and brought to America in 1761. Phillis was sold at a slave-market in Boston.

According to one source: "She was purchased by Mr. John Wheatley, a respectable citizen of Boston. This gentleman, at the time of the purchase, was already the owner of several slaves; but the females in his possession were getting something beyond the active periods of life, and Mrs. Wheatley wished to obtain a young negress, with the view of training her up under her own eye, that she might, by gentle usage, secure to herself a faithful domestic in her old age. She visited the slave-market, that she might make a personal selection from the group of unfortunates offered for sale. There she found several robust, healthy females, exhibited at the same time with Phillis, who was of a slender frame, and evidently suffering from change of climate. She was, however, the choice of the lady, who acknowledged herself influenced to this decision by the humble and modest demeanor and the interesting features of the little stranger."

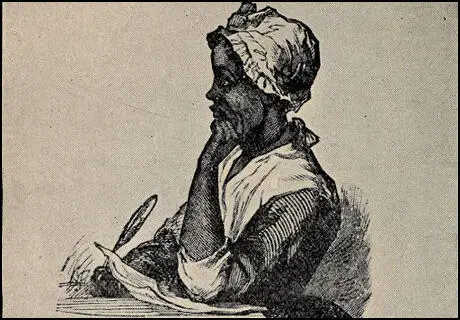

Phillis apparently "gave indications of uncommon intelligence, and was frequently seen endeavoring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal." Phillis was taught to read by one of Wheatley's daughters. Phillis studied English, Latin and Greek and in 1767 began writing poetry. Her first poem, on the death of George Whitefield, was published in 1770. When Phillis was eighteen she travelled to London and while there the Countess of Huntingdon, helped her publish a collection of her work, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773).

After the death of John Wheatley and his wife, Phillis married John Peters, a free black man, who ran a small grocery store in Boston. "At this period of destitution, Phillis received an offer of marriage from a respectable colored man of Boston. The name of this individual was Peters. He kept a grocery in Court-Street, and was a man of very handsome person and manners; wore a wig, carried a cane, and quite acted out 'the gentleman.' In an evil hour he was accepted; and he proved utterly unworthy of the distinguished woman who honored him by her alliance. He was unsuccessful in business, and failed soon after their marriage; and he is said to have been both too proud and too indolent to apply himself to any occupation below his fancied dignity. Hence his unfortunate wife suffered much from this ill-omened union." The business was unsuccessful and Phillis was forced to find work as a servant.

Phillis Wheatley died in poverty in Boston on 5th December, 1784.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) An account of the life of Phillis Wheatley was published by George Light in 1834.

Phillis Wheatley was a native of Africa; and was brought to this country in the year 1761, and sold as a slave. She was purchased by Mr. John Wheatley, a respectable citizen of Boston. This gentleman, at the time of the purchase, was already the owner of several slaves; but the females in his possession were getting something beyond the active periods of life, and Mrs. Wheatley wished to obtain a young negress, with the view of training her up under her own eye, that she might, by gentle usage, secure to herself a faithful domestic in her old age. She visited the slave-market, that she might make a personal selection from the group of unfortunates offered for sale.

There she found several robust, healthy females, exhibited at the same time with Phillis, who was of a slender frame, and evidently suffering from change of climate. She was, however, the choice of the lady, who acknowledged herself influenced to this decision by the humble and modest demeanor and the interesting features of the little stranger.

The poor, naked child (for she had no other covering than a quantity of dirty carpet about her like a fillibeg) was taken home in the chaise of her mistress, and comfortably attired. She is supposed to have been about seven years old, at this time, from the circumstance of shedding her front teeth. She soon gave indications of uncommon intelligence, and was frequently seen endeavoring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal.

A daughter of Mrs. Wheatley, not long after the child's first introduction to the family, undertook to learn her to read and write; and, while she astonished her instructress by her rapid progress, she won the good will of her kind mistress, by her amiable disposition and the propriety of her behaviour. She was not devoted to menial occupations, as was at first intended; nor was she allowed to associate with the other domestics of the family, who were of her own color and condition, but was kept constantly about the person of her mistress.

(2) Phillis Wheatley, The Memoirs of Phillis Wheatley (1834)

We cannot ascertain that she ever received any formal manumission; but the chains which bound her to her master and mistress were the golden links of love, and the silken bands of gratitude. She had a child's place in their house and in their hearts. Nor did she, notwithstanding their magnanimity in setting aside the prejudices against color and condition, when they found these adventitious circumstances dignified by talents and worth, ever presume on their indulgence either at home or abroad. Whenever she was invited to the houses of individuals of wealth and distinction, (which frequently happened,) she always declined the seat offered her at their board, and, requesting that a side-table might be laid for her, dined modestly apart from the rest of the company.

We consider this conduct both dignified and judicious. A woman of so much mind as Phillis possessed, could not but be aware of the emptiness of many of the artificial distinctions of life. She could not, indeed, have felt so utterly unworthy to sit down among the guests, with those by whom she had been bidden to the banquet. But she must have been painfully conscious of the feelings with which her unfortunate race were regarded; and must have reflected that, in a mixed company, there might be many individuals who would, perhaps, think they honored her too far by dining with her at the same table. Therefore, by respecting even the prejudices of those who courteously waived them in her favor, she very delicately expressed her gratitude; and, following the counsels of those Scriptures to which she was not a stranger, and taking the lowest seat at the feast, she placed herself where she could certainly expect neither to give or receive offence.

(3) Phillis Wheatley, The Memoirs of Phillis Wheatley (1834)

The decease of this excellent lady occurred in the year 1774. Her husband soon followed her to the house appointed for all living; and their daughter joined them in the chambers of death. The son had married and settled in England; and Phillis was now, therefore, left utterly desolate. She spent a short time with a friend of her departed mistress, and then took an apartment, and lived by herself. This was a strange change to one who had enjoyed the comforts and even luxuries of life, and the happiness of a fire-side where a well regulated family were accustomed to gather. Poverty, too, was drawing near with its countless afflictions. She could hope for little extraneous aid; the troubles with the mother country were thickening around; every home was darkened, and every heart was sad.

At this period of destitution, Phillis received an offer of marriage from a respectable colored man of Boston. The name of this individual was Peters. He kept a grocery in Court-Street, and was a man of very handsome person and manners; wore a wig, carried a cane, and quite acted out 'the gentleman.' In an evil hour he was accepted; and he proved utterly unworthy of the distinguished woman who honored him by her alliance. He was unsuccessful in business, and failed soon after their marriage; and he is said to have been both too proud and too indolent to apply himself to any occupation below his fancied dignity. Hence his unfortunate wife suffered much from this ill-omened union.

(4) Phillis Wheatley, On Being Brought from Africa to America (1773)

'T Was mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God--that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye--

'Their color is a diabolic dye.'

Remember, Christians, Negroes black as Cain

May be refined, and join the angelic train.

(5) Phillis Wheatley, Ode to Neptune (October, 1772)

While raging tempests shake the shore,

While Æolus' thunders round us roar,

And sweep impetuous o'er the plain,

Be still, O tyrant of the main;

Nor let thy brow contracted frowns betray,

While my Susannah skims the watery way.

The Power propitious hears the lay,

The blue-eyed daughters of the sea

With sweeter cadence glide along,

And Thames responsive joins the song.

Pleased with their note, Sol sheds benign his ray,

And double radiance decks the face of day.

To court thee to Britannia's arms,

Serene the clime and mild the sky,

Her region boasts unnumbered charms;

Thy welcome smiles in ev'ry eye.

Thy promise, Neptune, keep; record my prayer,

Nor give my wishes to the empty air.

(6) Phillis Wheatley, On the Death of George Whitefield (1770)

Hail, happy saint! on thine immortal throne,

Possest of glory, life, and bliss unknown;

We hear no more the music of thy tongue;

Thy wonted auditories cease to throng.

Thy sermons in unequalled accents flowed,

And ev'ry bosom with devotion glowed;

Thou didst, in strains of eloquence refined,

Inflame the heart, and captivate the mind.

Unhappy, we the setting sun deplore,

So glorious once, but ah! it shines no more.

Behold the prophet in his towering flight!

He leaves the earth for heaven's unmeasured height,

And worlds unknown receive him from our sight.

There Whitefield wings with rapid course his way,

And sails to Zion through vast seas of day.

Thy prayers, great saint, and thine incessant cries,

Have pierced the bosom of they native skies.

Thou, moon, hast seen, and all the stars of light,

How he has wrestled with his God by night.

He prayed that grace in ev'ry heart might dwell;

He longed to see America excel;

He charged its youth that ev'ry grace divine

Should with full lustre in their conduct shine.

That Saviour, which his soul did first receive,

The greatest gift that ev'n a God can give,

He freely offered to the num'rous throng,

That on his lips with list'ning pleasure hung.

"Take him, ye wretched, for your only good,

"Take him, ye starving sinners, for your food;

"Ye thirsty, come to this life-giving stream,

"Ye preachers, take him for your joyful theme;

"Take him, my dear Americans, he said,

"Be your complaints on his kind bosom laid:

"Take him, ye Africans, he longs for you;

"Impartial Saviour is his title due:

"Washed in the fountain of redeeming blood,

"You shall be sons, and kings, and priests to God."

Great Countess, we Americans revere

Thy name, and mingle in thy grief sincere;

New England deeply feels, the orphans mourn,

Their more than father will no more return.

But though arrested by the hand of death,

Whitefield no more exerts his lab'ring breath,

Yet let us view him in the eternal skies,

Let ev'ry heart to this bright vision rise;

While the tomb, safe, retains its sacred trust,

Till life divine re-animates the dust.