Priscilla Johnson McMillan

Priscilla Livingston Johnson, the third of four children, was born in Glen Cove, New York, on 19 July, 1928 and grew up in nearby Locust Valley, an affluent hamlet on Long Island. (1) Her father, Stuart H. Johnson, was a financier who inherited a textile company. Priscilla went to the private, all-girls Brearley School in New York City and was considered to be an excellent student. (2)

Johnson attended Bryn Mawr College and graduated in 1950. She went on to study Russian literature at Radcliffe College, Harvard University. While she was a student Johnson became a member of the United World Federalists (UWF), an organization advocating world government. The president of the UWF was Cord Meyer: "My reason for making such an abrupt change in my career was a conviction that the United States, through its atomic monopoly, had for a brief period the opportunity to lead the world toward effective international control of the bomb." (3)

Priscilla Johnson and the CIA

After graduating from Harvard with a master's degree in 1952 she applied to join the Central Intelligence Agency. On 3rd October, 1952, a request was submitted for a security clearance as an "Intelligence Officer, GS-7" in Operations to work in the Soviet Realities Division of the CIA. On 21 January, 1953, this was changed to a request for a security clearance for Johnson (CIA number as 71589) to work as an Intelligence Officer. On the same day, Bruce L. Solie responded that Johnson had "declined employment on 21 January 1953". A formal cancellation was put in her file on 10 February and it was said "it is not believed there is any CE interest in subject case." (4)

The following month W. A. Osborne, chief of the Security Branch, sent a memo to Deputy Chief, Security Division, requesting that her "case be reviewed from a CE (counter-espionage) aspect." (5) On 17 March, 1953, Osborne sent a memo to Sheffield Edwards, head of CIA security, that after checking out Johnson's associates he recommended approval. "She's active politically (i.e. interested in domestic and international politics) but is not and has not been tied in with subversive groups... While a member of UWF, she does not appear to be objectionally internationalistic." (6)

Later that month Osborne sent out another memo to Edwards that was completely at odds with the one sent six days previously: "The most serious question raised by investigation and research is that of her associates. It is felt that these associations being considered in the light of her activities in the United World Federalists, her attendance at questionable schools and her activities in the League for Industrial Democracy raise a question regarding her eligibility which should be resolved in favor of the Agency. It is, therefore, recommended that she be disapproved." (7)

Although Johnson was apparently rejected, Cord Meyer, her former leader at the United World Federalists, was recruited by the CIA after an interview with Allen W. Dulles "we had a number of friends in common at whose houses we had played tennis together on Long Island weekends." He was then assigned to work under Frank Wisner, director of the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), the espionage and counter-intelligence branch of the CIA. In his autobiography Meyer admitted: "It was an exhilarating atmosphere in which to work." (8)

Wisner was told to create an organization that concentrated on "propaganda, economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world." As David Corn, the author of Blond Ghost (1994) pointed out: "The OPC was let loose and frantically moved to slip $1 million in secret funds to pro-American, noncommunist political parties... Under the leadership of Frank Wisner... the OPC grew into... a grand instrument that could... mount operations, rig elections, control newspapers, sway opinion." (9)

Johnson later told John M. Newman that Meyer was "the brains behind the CIA program to fund left-wing publications." The umbrella organization for these publications, according to Johnson, was the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the "covert" source for its funds. Its publications were "respected Cold War liberal" journals, she recalled, "like Encounter and Survey, which I did some writing for." (10)

Thomas Braden, the head of the International Organizations Division (IOD), was placed in charge of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The objective of the IOD was to control potential radicals and to steer them to the right. Braden later admitted that the CIA was putting around $900,000 a year into the Congress of Cultural Freedom. Some of this money was used to publish its journal, Encounter. Braden pointed out: "If the director of CIA wanted to extend a present, say, to someone in Europe - a Labour leader - suppose he just thought, This man can use fifty thousand dollars, he's working well and doing a good job - he could hand it to him and never have to account to anybody... Since it was unaccountable, it could hire as many people as it wanted.... It could hire armies; it could buy banks. There was simply no limit to the money it could spend and no limit to the people it could hire and no limit to the activities it could decide were necessary to conduct the war - the secret war.... It was a multinational. Maybe it was one of the first. Journalists were a target, labor unions a particular target." (11)

John F. Kennedy

In 1953 Priscilla Johnson joined the Senate staff of John F. Kennedy, then a newly elected Democrat from Massachusetts. "Like many idealistic young people right after World War II, I was a World Federeralist and hoped that the Soviet Union could be persuaded to join a world government.. My first job was in Washington as a researcher for the newly elected senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy." (12) Kennedy was "mesmerizing," she later said; while she worked only briefly on Capitol Hill, "she visited him in the hospital when he underwent spinal surgeries, and posed as one of his sisters to get past a line of nurses and bring newspapers to his bedside." (13)

The following year Johnson worked as a translator for the Digest of Soviet Press (weekly presentation of select Russian-language press materials, carefully translated into English). Although no longer employed by Kennedy she visited him in hospital during the winter of 1954-1955 when he was undergoing two operations on his spine. "One of the doctors I knew begged Kennedy not to go through with the first operation. And Kennedy, about to be wheeled into surgery, said simply: 'I'd rather die than go around the rest of my life on crutches'. That winter he did almost die, several times. I went to see him, posing as one of his sisters, whenever he asked me to come or whenever I heard that he was better."

Johnson continued to see Kennedy after he left hospital: "I was one of hundreds of friends in his life; he was unique in mine. Because he was unique, I thought about him a good deal. Aside from his humor and his Irish irascibility, the characteristic of Jack's of which I saw most was his wide-ranging curiously. Should we give aid to Yugoslavia? With whom was I going skiing that weekend? At what age did I expect to get married?" A nurse told Priscilla: "He's supposed to see no one but family But he has such an enormous family - especially sisters." (14)

Lee Harvey Oswald

In 1955 Johnson moved to the Soviet Union where she worked as a translator for the U.S. Embassy in Moscow. This time the CIA made no objection to Johnson having access to classified information. In fact, on August, 1956, the chief of CI/Operational Approval and Support Division, asked for approval of operational use of Johnson in the Soviet Union. Robert Cunningham of the Security Office sent a memo pointing out that Johnson "is of potential interest". However, the words that followed were redacted. (15)

In February 1958 Johnson traveled to Cairo. "I went to Cairo in February 1958 I went to Paris, and did a little translating in a building on Haussmann Boulevard." She admitted that she worked for "someone I knew either for Radio Liberty or the Congress for Cultural Freedom". (16) While in France she applied to the USSR consulate to go to the Soviet Union. On 5 May, 1958, the Chief of CI/OA submitted a request for operational approval on Johnson. "Subject (Johnson) has applied for a visa to study or work in the USSR. The visa has been granted and subject intends to depart for Moscow within the next two weeks. We wish to recruit subject before her departure and brief her on positive and operational intelligence requirements. Priority clearance is requested because of the time element involved." The operation for which she was being considered is still classified. (17)

The CIA continued to keep a close watch on Johnson. In a memo from headquarters to an unnamed CIA station in Europe it produced an account of what it knew of her: "DOB July 1928. MA Radcliffe 1952. From wealthy Long Island Family. Excellent scholastic rating. Application for KU-BARK (codename for the CIA) employment 1952 rejected because some associates and memberships would have required more investigation than thought worthwhile. Once a member of United World Federalists; thought liberal, international-minded, anti-communist." (18)

Johnson arrived in Moscow for the third time on 4 July, 1958. She did not stay for long and returned to the United States. Soon afterwards she obtained employment as a reporter for the North American News Alliance (NANA). According to Bill Simpich, "NANA has a bad reputation as a hotbed of intelligence". (19) Johnson arrived back in Moscow soon after Arline Mosby had interviewed Lee Harvey Oswald (13 November, 1959). Mosby commented that "some of Oswald's statements sounded rehearsed (a claim that others would make), and she told of Oswald's boast that he saved the $1,500 necessary for the trip." (20)

On her arrival Johnson checked into the same hotel as Oswald. The following day she visited the American Embassy to pick up her mail (16 November, 1959). According to Johnson, John McVickar approached her and told her that "there's a guy in your hotel who wants to defect, and he won't talk to any of us here". She later told the Warren Commission: "John McVickar said she was refusing to talk to journalists. So I thought that it might be an exclusive, for one thing, and he was right in my hotel, for another." As Johnson was leaving the American Embassy McVickar told her to remember that "there was a thin line duty as a correspondent and as an American." (21)

Lee Harvey Oswald agreed to be interviewed by Priscilla Johnson. She later testified that they talked from between nine until one or two in the morning. "I was astounded by his lack of curiosity and the utter absence of any joy or spirit of adventure in him.... I was sorry for him, too, for I was certain he was making a mistake. He told me that he had been informed that morning that he did not have to leave the country. So I supposed that he would soon be granted citizenship, vanish into some remote corner of Russia, and never be heard from again. He would not be allowed to see any Americans, much less reporters, and he would be unable to signal his distress. Like every Westerner in Moscow, I had heard innumerable tragic stories about foreigners who had come to Russia during the 1930s, crossed the Rubicon of Soviet citizenship, and never been allowed to leave. I assumed that Lee would regret his choice and that he, like the others, would be trapped. As young as he was, he would have a lifetime to be sorry." (22)

Priscilla Johnson's article appeared in the Washington Evening Star. Surprisingly, the article did not include Oswald's threat to reveal radar secrets. However, under oath before the Warren Commission she admitted that "I had the impression, in fact he (Oswald) said, he hoped his experience as a radar operator would make him more desirable to them (the Soviets). That was the only thing that really showed any lack of integrity in a way about him, a negative thing. That is, he felt he had something he could give them, something that would hurt his country in a way, or could, and that was the one thing that was quite negative, that he was holding out some kind of bait." (23)

When the historian and former intelligence officer, John M. Newman, asked Johnson in an interview in 1994 why she had not included Oswald's threat to reveal radar secrets in several articles and her book, Marina and Lee (1977) she replied: "I know, that it is terrible, that is so unprofessional." Newman adds that "her recollection was at first indecisive, and she wondered if it had not been 'wrong to tell the Warren Commission that.' At length, however, she stuck with her testimony." Newman concluded: "What emerges from this testimony is that Priscilla was predisposed against doing a critical story on Oswald, so much so that contrary to a reporter's instincts to get the most dramatic story, she deliberately ignored Oswald's stated intent to commit a disloyal act." (24)

Priscilla Johnson continued to have a close relationship with the CIA. On 25 May 1962, the chief of the CIA's Covert Action (CA) Staff sent a request to the CI/OA Support Division for a proprietary operational approval to use Johnson as news editor and writer for a publication under QKOPERA. (25) According to Frances Stonor Saunders: "QKOPERA, often linked to the LCPIPIT program for journalist 'songbirds' based in Paris, refers to the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Touted as a pushback against Communist influence in the arts, it was a Western version of psychological warfare aimed at winning the hearts and minds of the general public... Its agents were placed in the film industry, in publishing houses, even as travel writers for the celebrated Fodor guides." (26)

As Peter R. Whitmey has pointed out: "In August, 1993, thousands of pages of CIA documents were made available to researchers at the National Archives that had been previously classified, including several documents associated with Priscilla Johnson McMillan... The first document, dated December 11, 1962 (and numbered 17456), is a 'contact report,' previously classified 'secret,' written by Donald Jameson, Chief SR/CA, which possibly stands for 'Soviet Russia/Covert Actions.' The report is based on a 90 minute meeting with Priscilla Johnson in her room at the Brattle Inn, located in Cambridge, Massachusetts." (27)

The memo written by Donald Jameson reported: "I think that Miss Johnson can be encouraged to write pretty much the articles we want. It will require a little more contact and discussion, but I think she could come around... Basically, if approached with sympathy in the cause she considers most vital, I believe she would be interested in helping us in many ways. It would be important to avoid making her think that she was being used as a propaganda tool and expected to write what she is told. I don't think she would go along with that idea at all. On the other hand, she is searching for both more information and more understanding of the problem of the Soviet intellectual and is consequently subject to influence." (28)

Another CIA document dated dated 5 February, 1964, reports on a 11 hour meeting with Johnson. The main objective of the meeting was to debrief Johnson "on her flaps with the Soviets when she was in the USSR, notably at the time of her last exit." She was also asked if she "would be interested in writing articles for Soviet publications." Gary Coit, the CIA officer who conducted the interview with Johnson reported that "no effort was made to attempt to force the issue of a debriefing on her contacts". However, Coit told her he would "probably be back to see her from time to time to see what she knows about specific persons whose names might come up, and she at least nodded assent to this." (29)

Marina Oswald

John F. Kennedy was assassinated on 22 November, 1963. Johnson was convinced that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone-gunman. "I needed to reconcile the quiet, rather gentle Lee, the boy whom I had met in my hotel room and who told me he was unemotional, with the dangerous Oswald, the man who shot the President. I was not at all sure how they fitted. I wanted to understand why Lee did it - first of all for myself and then, even though he was dead, for President Kennedy. If there was an answer to the question, I thought that Marina Oswald might be the one who could help find it. And so, through the offices of my publisher and her lawyer, I arranged to meet her with a view to writing a book." (30)

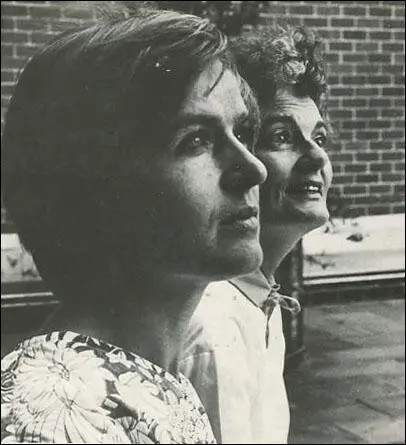

In July 1964 Johnson moved to Texas and befriended Marina Oswald, and the two spent considerable time together. According to Bryan Marquard: "After Kennedy was slain, and Oswald murdered a couple of days later, she conducted extensive interviews with Marina Oswald, even living with the assassin's widow for several months. She granted such access because Mrs. McMillan was fluent in Russian (Marina spoke little English), had known Lee, and had known JFK, who had been a source of fascination for the Oswalds." (31)

In November 1964, Johnson signed a contract with Harper & Row for a book to be published about the Oswalds, with two-thirds of the advance going to Marina. In 1966 Johnson married George McMillan (1913-1987), a freelance writer who covered the Civil Rights Movement in the American South and was the author of The Making of an Assassin (1976) about James Earl Ray, the killer of Martin Luther King Jr. (32)

Frank Church Committee

McMillan's book was expected to be published in 1965, however, it seemed that the project seemed to me more about keeping Marina from going public about her doubts about her husband being the lone gunman responsible for the assassination of Kennedy. When Joseph Stalin's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, escaped to the United States McMillan was brought in to help translating her bestselling 1967 memoir Twenty Letters to a Friend. As the Irish Times pointed out this "prompted many researchers to point to Johnson's close ties to the US intelligence community." (33)

In 1975, Frank Church became the chairman of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. This committee investigated alleged abuses of power by the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Intelligence. They discovered that the FBI was involved in the assassination of Fred Hampton, one of the leaders of the Black Panthers. (34)

Church's committee also discovered that the CIA and the FBI had sent anonymous letters attacking the political beliefs of targets in order to induce their employers to fire them. Similar letters were sent to spouses in an effort to destroy marriages. The committee also documented criminal break-ins, the theft of membership lists and misinformation campaigns aimed at provoking violent attacks against targeted individuals. One of those people targeted was Martin Luther King. The FBI mailed King a tape recording made from microphones hidden in hotel rooms. The tape was accompanied by a note suggesting that the recording would be released to the public unless King committed suicide. (35)

In September, 1975, a subcommittee under Richard Schweiker was asked to investigate the performance of the intelligence agencies concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy. This created panic in the CIA and in one document declassified in April 1999, the CIA raised concern about McMillian appearing before the committee: "Priscilla Johnson McMillan may be called to discuss her contacts with Oswald in Moscow at which time her CIA "witting source" affiliation may be exposed. She gave executive session testimony last week, and staff indicated that they had follow-up issues as a result but would not share their issues. If the CIA relationship is presented, Gary Coit (retired, DCD) may be subpoenaed." (36) This was a reference to Johnson's 201 file dated 28 January, 1975: "In accordance with the DDO's notice of 9 December 1974, I have reviewed the 201 file on (Priscilla Johnson) and have determined that it can most accurately be categorized as indicated below as a 'witting collaborator' (01 Code A1)." (37)

In a report, issued in April 1976, the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities concluded: "Domestic intelligence activity has threatened and undermined the Constitutional rights of Americans to free speech, association and privacy. It has done so primarily because the Constitutional system for checking abuse of power has not been applied." The committee also revealed details for the first time of what the CIA called Operation Mockingbird (a secret programme to control the media). (38) Michael Carlson has pointed out that Johnson testified in closed session; and "large sections of her HSCA testimony are redacted whenever she is asked about her intelligence connections." (39)

Marina and Lee did not appear until 1977. In the book she argued that Oswald had assassinated the president and had acted alone. According to The Times: "Marina and Lee: The Tormented Love and Fatal Obsession Behind Lee Harvey Oswald's Assassination of John F. Kennedy attracted glowing reviews but did not sell well, primarily because it offered no conspiracy theories. McMillan concluded that Oswald was working for no one and was merely a troubled, celebrity-seeking fantasist who was quite incapable of conspiring with others and believed that he could destroy capitalism by killing the president." (40)

Harrison Smith of the The Washington Post took a similar view of the book: "By the time Mrs. McMillan published her book, conspiracy theories had proliferated about the killing. There seemed to be little appetite for her relatively straightforward account of a wayward, self-described Marxist; sales were modest." (41) Despite this it has been claimed that the book "became a key document in establishing Oswald as a lone disturbed assassin". (42)

However, a later assessment in the Irish Times took a more naunced view: Johnson wrote of Oswald's "unfitness for any conspiracy outside his own head". The article adds: "oddly enough, the description also would suit a hapless someone who was, as Oswald himself claimed, a 'patsy'." It was also pointed out that later Marina began to distance herself from Johnson's conclusions, saying she was "misled by the ‘evidence' presented to me by government authorities... I am now convinced Lee was an FBI informant and did not kill president Kennedy." (43)

The book got a very good review from CIA friendly journalist, Thomas Powers, in the New York Times: "Priscilla Johnson McMillan has written, miraculous because McMillan had the wit, courage and perseverance to go hack to the heart of the story, and the art to give It life. The Oswald who emerges in McMillan's book was a young man badly put together - erratic, lonely, proud, impatient and violent. His ambitions were soaring, his abilities uncertain, his education limited to what he had picked up in public libraries despite a reading disability called dyslexia. From the age of 15 he considered himself a Marxist-Leninist."

Powers attacked those who refused to accept Johnson's view of the assassination: "The skeptics, I suspect, are in no mood to be convinced: The word is already out on McMillan in buff circles. Her book can he dismissed. She is unreliable, not to he trusted. She may have been working for the 'State, Department' - of worse - when she had an interview with Oswald in Moscow back in October 1959, On top of that McMillan's principal source was Marina Oswald, who was the niece of a colonel in the M.V.D.... The people who are taking this position ought to be ashamed of themselves; they are accusing McMillan of the same failings - either secret motives or ad-hominem arguments - so often brought against themselves. The argument is confusingly circular: you can't trust the book because you can't trust McMillan, and you can't trust McMillan because you can't trust Marina. That follows only you assume Marina was a witting party to conspiracy to kill Kennedy. If you don't believe that - and very few assassination buffs do; they look tot the villains elsewhere - then tier testimony is as good as anyone's else."

As Powers points out: "McMillan never seems ever to have doubted for a moment that Oswald did it, or that he did it for reasons of his own. He had his 'ideas' - he seems to have rationalized the assassination as a salutary shock for a complacent public - but his real motive emerges as a desperate desire to transcend the obscurity and impotence to which fate was inexorably confining him. A failure in every job he held, in danger of driving away his wife and child, ignored or condescended to whenever he brought up his 'ideas,' reluctantly accepters by the Russians in 1959 and rejected by the Cubans in 1963, Oswald refused to slip under with only a whimper. He killed Kennedy for the same reason he fired a shot at Walker: to prove he was there, and counted." (44)

David Kaiser, the author of The Road to Dallas (2008) considered Johnson's book as an unreliable source: "From 1964 until the present, lone-assassin theorists have relied a great deal on the testimony of Marina Oswald to explain her husband's behaviour in 1963. But the release of the original FBI investigative reports has cast considerable doubt on the story she told the Warren Commission in February 1964, and even more on the detailed account of her life with Oswald that she gave to Priscilla Johnson McMillan during the next fourteen years." (45)

Other books by Priscilla Johnson McMillan include Khrushchev and the Arts (1965) and The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer: And the Birth of the Modern Arms Race (2005). Articles by her have been published in Harper's Magazine, The Reporter, The New York Times, The Washington Post and Boston Globe. The director of the Cold War Studies Project at Harvard University's Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Mark Kramer, has argued: "Priscilla combined the best traits of an investigative reporter, a scholar and an inquisitive citizen, pursuing exhaustive research and doing her best to be fair to all parties." (46)

The Cover-Up

In January 1975 (released in 1993) a CIA document described Priscilla Johnson as "Witting Collaborator 01 code A1". (47) In Marina and Lee (1977) McMillan gave the impression that Marina Oswald believed her husband was solely responsible for the killing of John F. Kennedy. However, it later became clear that she had considerable doubts about this theory. In January 1981, she made contact with David Lifton, the author of Best Evidence: Disguise and Deception in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy (1980). Marina telephoned Lifton many times each month and she eventually became convinced that he was not the lone gunman that killed Kennedy. (48)

In an interview Marina gave to the Ladies Home Journal in September 1988 she argued: ''I'm not saying that Lee is innocent, that he didn't know about the conspiracy or was not a part of it, but I am saying he's not necessarily guilty of murder. At first, I thought that Jack Ruby (who killed Oswald two days after the assassination) was swayed by passion; all of America was grieving. But later, we found that he had connections with the underworld. Now, I think Lee was killed to keep his mouth shut." Marina added: '' I believe he worked for the American government... He was taught the Russian language when he was in the military. Do you think that is usual, that an ordinary soldier is taught Russian? Also, he got in and out of Russia quite easily, and he got me out quite easily.'' (49)

Marina Oswald gave a television interview with David Lifton on Hard Copy the American television show in 1990. She claimed that her husband adored John F. Kennedy: ""I can't in my mind, I could never put Lee against Kennedy. That never made sense to me." (50) Three years later she was interviewed by Tom Brokaw on NBC. Marina Oswald was even more adamant that her husband didn't kill the president and claimed he had been framed. "He definitely did not fire the shots", she said. (51)

In April 1996 Marina wrote to John Tunheim, chairman of the Assassination Records Review Board. "The time for the Review Board to obtain and release the most important documents related to the assassination of President Kennedy is running out. At the time of the assassination of this great president whom I loved, I was misled by the 'evidence' presented to me by government authorities and I assisted in the conviction of Lee Harvey Oswald as the assassin. From the new information now available, I am now convinced that he was an FBI informant and believe that he did not kill President Kennedy. It is time for Americans to know their full history. On this day when I and all Americans are grieving for the victims of Oklahoma City, I am also thinking of my children and grandchildren, and of all American children, when I insist that your board give the highest priority to the release of the documents I have listed. This is the duty you were charged with by law. Anything else is unacceptable - not just to me, but to all patriotic Americans." (52)

Priscilla Johnson McMillan was interviewed by William L. Joyce at the Assassination Records Review Board in March, 1995. Joyce pointed out that "there have been several statements to the effect that you might have had a connection to the Central Intelligence Agency. I was wondering if you could elucidate the nature of them and whether you might have had any conversations with the CIA concerning Oswald in connection with the Soviet Union or Cuba." McMillan denied this but admitted that she had met two CIA officers, Donald Jameson and Gary Coit (researchers already knew this because of CIA declassified documents). (53)

Despite this McMillan continued to argue that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone-gunman. In an interview given in November, 2013, she explained that after spending thirteen years with Marina in Texas, McMillan's conclusion was that Oswald was the lone assassin. "I'm just as sure now as I was then that he did it, and also that he couldn't have done it with anybody else. He wasn't somebody who, in his life, had ever done anything with anybody else." (54)

Thomas Powers, her friendly reviewer in the New York Times, also remained convinced that McMillan was right and arranged for his Steerforth Press, to reissued Marina and Lee in 2013. Powers said her "portrait of what actually happened, of course, won endless numbers of enemies for Priscilla, including many who tried to claim she was part of a conspiracy and had worked for the CIA." (55)

Priscilla Johnson McMillan died after a fall at her home in Cambridge on 7th July, 2021.

Primary Sources

(1) Donald Jameson, Chief SR/CA, memo, marked top secret (11th December, 1962)

I think that Miss Johnson can be encouraged to write pretty much the articles we want. It will require a little more contact and discussion, but I think she could come around... Basically, if approached with sympathy in the cause she considers most vital, I believe she would be interested in helping us in many ways. It would be important to avoid making her think that she was being used as a propaganda tool and expected to write what she is told. I don't think she would go along with that idea at all. On the other hand, she is searching for both more information and more understanding of the problem of the Soviet intellectual and is consequently subject to influence.

(2) Internal CIA memorandum (201-102798) on Priscilla Johnson McMillan (28th January 1975) (released in 1993)

In accordance with the DDO's notice of 9 December 1974, I have reviewed the 201 file on (Priscilla Johnson) and have determined that it can most accurately be categorized as indicated below "witting collaborator" 01 Code A1.

(3) Priscilla Johnson McMillan, Marina and Lee (1977)

On November 13 Lee telephoned Aline Mosby, a reporter for United Press International; she came to see him, and he talked to her "non-stop" for two hours. And, on November 16, a Soviet official came to his room and informed him that he could remain until a decision had been made what to do with him. It was virtually a promise that he could stay, and Lee was vastly relieved.

I happened to be the beneficiary of his relief. I was a newspaper and magazine reporter in Moscow in 1959. I had just returned from a visit to the United States and, on November 16, I went to the consular office of the American Embassy, as the American reporters did, to pick up my mail. John McVickar welcomed me back with these words: "Oh, by the way, there's a young American in your hotel trying to defect. He won't talk to any of us, but maybe he'll talk to you because you're a woman."

McVickar turned out to be right. At the Hotel Metropole I stopped by Oswald's room, which was on the second floor, the floor below my own. I knocked, and the young man inside opened the door. Instead of inviting me in, he came into the corridor and stood there, holding the door open with his foot. I peeked into his room, and saw that it was exactly like mine, right down to its shade of hotel blue. To my surprise, he readily agreed to be interviewed, and said that he would come to my room at eight or nine o'clock that evening. Good as his word he appeared, wearing a dark gray suit, a white shirt with a dark tie, and a sweater-vest of tan cashmere. He looked familiar to me, like a lot of college boys in the East during the 1950s. The only difference was his voice-he had a slight Southern drawl.

He settled in an armchair, I brought him tea from a little burner I kept on the floor, and he started talking fairly easily. He spoke quietly, unemphatically, and only rarely betrayed by a gesture or a slight change of tone that what he was saying at that moment meant anything special to him. He began by complaining about Richard Snyder and his refusal to accept on the spot his oath of renunciation. I had no idea what he was talking about, since I had not discussed him with Snyder or McVickar, nor heard about the stormy scene at the embassy two weeks before."

During our conversation Lee returned again and again to what he called the embassy's "illegal" treatment of him, which he termed a "prestige and labor-saving device." He spread out two letters on my desk: one his letter of protest to the American ambassador, Llewellyn Thompson, and the other his letter from Snyder, which said that he was free to come to the embassy at any time and take the oath. Well, I said, all you have to do is go back one more time. He swore he would never set foot there again. Once he became a Soviet citizen, he said, he would allow "my government," the Soviet government, to handle it for him.

Lee's tone was level, almost expressionless, and while I realized that his words were bitter, somehow I did not feel that he was angry. Moreover, he did not seem like a fully grown man to me, for the blinding fact, the one that obliterated nearly every other fact about him, was his youth. He looked about seventeen. Proudly, as a boy might, he told me about his only expedition into Moscow alone. He had walked four blocks to Detsky Mir, the children's department store, and bought himself an ice cream cone. I could scarcely believe my ears. Here he was, coming to live in this country forever, and he had so far dared venture into only four blocks of it.

I was astounded by his lack of curiosity and the utter absence of any joy or spirit of adventure in him. And yet I respected him. Here was this lonely, frightened boy taking on the bureaucracy of the second most powerful nation on earth, and doing it single-handedly. I wondered if he had any idea what he was doing, for it could be brutal to try to stay if the Russians did not want you-futile and dangerous. I had to admire Lee, ignorant, young, and even tender as he appeared, for persisting in spite of so many discouragements.

I was sorry for him, too, for I was certain he was making a mistake. He told me that he had been informed that morning that he did not have to leave the country. So I supposed that he would soon be granted citizenship, vanish into some remote corner of Russia, and never be heard from again. He would not be allowed to see any Americans, much less reporters, and he would be unable to signal his distress. Like every Westerner in Moscow, I had heard innumerable tragic stories about foreigners who had come to Russia during the 1930s, crossed the Rubicon of Soviet citizenship, and never been allowed to leave. I assumed that Lee would regret his choice and that he, like the others, would be trapped. As young as he was, he would have a lifetime to be sorry.

(4) Thomas Powers, New York Times (30th October, 1977)

Things began to go wrong when John F. Kennedy was murdered in November 1963, but not in the way you might think. We recovered from Kennedy's loss quickly enough, but we're still suffering from the questions left open by his death. Everybody has his own theory about the murder, some of them baroque in their conspiratorial complexity, some pugnaciously dismissive. My own theory is that Kennedy's murder marked the moment when we stopped thinking about what we might become as a nation, and start looking for whom to blame.

It is not just easy, but almost irresistible, to make fun of the Kennedy assassination skeptics, with their Oswald doubles and triples, the ectoplasmic gunmen on the grassy knoll, the phantom C.I.A. agents hovering over Oswald's shoulder, the logical proof that and war; now they are hunting villains among the ectoplasm. If that strikes you as funny, well ... it doesn't me.

I realize this is a long preamble for another hook about the Kennedy assassination, but I wish it were miraculous hook Priscilla Johnson McMillan has written, miraculous because McMillan had the wit, courage and perseverance to go hack to the heart of the story, and the art to give It life.

The Oswald who emerges in McMillan's book was a young man badly put together - erratic, lonely, proud, impatient and violent. His ambitions were soaring, his abilities uncertain, his education limited to what he had picked up in public libraries despite a reading disability called dyslexia. From the age of 15 he considered himself a Marxist-Leninist. His "ideas" were unsophisticated, bits and pieces of naive leftism, but he treasured them the way a lonely boy might treasure his collection of baseball cards.

Often unemployed, fired from the only job he ever liked and bored to distraction with the rest, Oswald spent hundreds of hours working on his "ideas," drawing up manifestoes and political programs, analyzing the failures of Soviet society as he saw them, working in a radio factory in Minsk after his defection to Russia in 1959. His dyslexia forced him to copy and recopy everything he wrote, and even then his letters and half-finished essays were riddled with what appear to be the spelling errors of a near illiterate.

In Russia Oswald had married Marina for reasons of convenience. Marina liked Oswald because he was neat and polite, because he was an American and made her girlfriends envious and because he was the only man she had ever known with an apartment of his own. This was no small matter in overcrowded Russia. Marina's uncle, a colonel in the M.V.D. (Ministry of Internal Affairs), had already rejected one of Marina's suitors out of hand because he had no apartment; the colonel resented Marina's presence in his home and made it clear that he certainly didn't want a nephew-In-law moving in as well. Looked at from the outside, the marriage was a disaster from the beginning. Oswald was secretive, overbearing and short-tempered. After he returned to the United States with his wife and young daughter in the summer of 1962, a streak of physical cruelty emerged. He horrified the Russian community of Dallas, where they moved, by the ferocity with which he sometimes beat his wife, by his cruel refusal to let Marina learn English or make friends of her own, and later, in 1963, by his threat to send her back to Russia alone.

Life with Oswald was so bad Marina frequently threatened to leave him for good, but at the same time she loved him, blamed herself for their arguments, pitied his loneliness, forgave his violence, hoped Oswald would outgrow the "ideas" that no one but he took seriously. Once, in the summer of 1963, when their relationship was strained to the snapping point, Marina found Oswald in the kitchen, sobbing inconsolably. Life defeated him at every turn; he didn't know what to do. She took him in her arms, comforted him, told him it would be all right, they would find a way. Twisted and painful as it was, Oswald's relationship with Marina was the closest to being normal of any throughout his life.

Marina was familiar enough with Oswald's "ideas" but she did not grasp his desperate readiness to act on them until April 1963. Earlier that year Oswald had ordered a pistol by mail, and later a rifle and four-power telescopic sight, in the name of "A. J. HideII," apparently chosen because it rhymed with Fidel, the name he wanted to give the son he expected.

On Wednesday, April 10, 1963, Oswald confessed to Marina with tears in his eyes that he had lost his job in a photo studio, the only one he had ever liked. That night he failed to come home at the usual time. Marina found a note in Russian on his desk, giving meticulous instructions about how she was to live in his absence. "If I am alive and taken prisoner." the note concluded, "the city jail is at the end of the bridge we always used to cross when we went to town...."

"At 11:30," McMillan writes, "Lee walked in, white, covered with sweat, his eyes glittering.

"'What's happened?' Marina asked.

"'I shot Walker.' He was out of breath and could hardly get out the words.

"'Did you kill him?'

"'I don't know.' "

The next day - half relieved, half disappointed � Oswald learned he had missed. Typically, he blamed his target. At the last moment, he told Marina, Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker, U.S.A. (Ret.), a champion of the John Birch Society, had moved his head. There was a flurry of notices in the press, but no evidence turned up to implicate Oswald. Later he showed Marina the elaborate plan he'd drawn up for Walker's murder complete with maps and photographs and a statement of Oswald's political "ideas." Marina made him bunt the incriminating documents, but she kept his note of instructions and made him swear never to do such a thing again

McMillan's description of this episode is characteristic of her hook, rich in brilliant detail, passionate and compelling. Oswald's desperate personal unhappiness before his attempt. the emotional aftershock (tot one whole night ht was literally in convulsions), the rain; that followed, are all on a piece. They describe a man with capacity - not reasons - for murder. McMillan; painstaking, intimate account of Oswald's last months prove one simple, important point: he was no phantom but a man with an hour-by-hour-existence like any other. If she does not know exactly why he wanted to kill Walker or Kennedy - how is one to extract a reason from the irrational?

Or made me see, at any rate. The skeptics, I suspect, are in no mood to be convinced: The word is already out on McMillan in buff circles. Her book can he dismissed. She is unreliable, not to he trusted. She may have been working for the "State, Department" - of worse - when she had an interview with Oswald in Moscow back in October 1959, On top of that McMillan's principal source was Marina Oswald, who was the niece of a colonel in the M.V.D. (Marina believes he was in charge or convict labor working on timber projects in Byelorussia.) How can you trust the work of someone working for the "State Monument based on information iron, the niece of a colonel ii the M.V.D.?

The people who are taking this position ought to be ashamed of themselves; they are accusing McMillan of the same failings - either secret motives or ad-hominem arguments - so often brought against themselves. The argument is confusingly circular: you can't trust the book because you can't trust McMillan, and you can't trust McMillan because you can't trust Marina. That follows only you assume Marina was a witting party to conspiracy to kill Kennedy. If you don't believe that - and very few assassination buffs do; they look tot the villains elsewhere - then tier testimony is as good as anyone's else....

McMillan never seems ever to have doubted for a moment that Oswald did it, or that he did it for reasons of his own. He had his "ideas" - he seems to have rationalized the assassination as a salutary shock for a complacent public - but his real motive emerges as a desperate desire to transcend the obscurity and impotence to which fate was inexorably confining him. A failure in every job he held, in danger of driving away his wife and child, ignored or condescended to whenever he brought up his "ideas," reluctantly acceptors by the Russians in 1959 and rejected by the Cubans in 1963, Oswald refused to slip under with only a whimper. He killed Kennedy for the same reason he fired a shot at Walker: to prove he was there, and counted.

It is not at all easy to describe the power of Marina and Lee. Its texture is rich and convincing, as painful as the events it describes. It is far better than any book about Kennedy, with the unsettling result that the assassination is experienced from the wrong end. McMillan follows Oswald's life with such fidelity and perception that it is his death which hurts in her final pages, not Kennedy's. Other books about the Kennedy assassination are all smoke and no fire, "Marina and Lee" burns. If you can find the heart to read it, you may finally begin to forget the phantom gunmen on the grassy knoll.

(5) Rodger S. Gabrielson, House Select Committee on Assassinations – A Projection (OLC 78-1544) (26th April, 1978) (Released on 13th April 1999)

Priscilla Johnson McMillan may be called to discuss her contacts with Oswald in Moscow at which time her CIA "witting source" affiliation may be exposed. She gave executive session testimony last week, and staff indicated that they had follow-up issues as a result but would not share their issues. If the CIA relationship is presented, Gary Coit (retired, DCD) may be subpoenaed.

(6) Peter R. Whitmey, Priscilla Johnson McMillan and the CIA (September, 1994)

In August, 1993, thousands of pages of CIA documents were made available to researchers at the National Archives that had been previously classified, including several documents associated with Priscilla Johnson McMillan, author of Marina and Lee, and the subject of several earlier articles by this writer.

The first document, dated December 11, 1962 (and numbered 17456), is a "contact report," previously classified "secret," written by Donald Jameson, Chief SR/CA, which possibly stands for "Soviet Russia/Covert Actions." The report is based on a 90- minute meeting with Priscilla Johnson in her room at the Brattle Inn, located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was pointed out that, according to Mr. Butler at the "OO Office" in Boston, Priscilla was "... allowed to use the Harvard-Russian Research Center for her own work, mainly the writing of articles and a book, but that she has no other official relationship to the center."

Jameson described Priscilla as being "able, astute and conscientious," reflected also in her writing, but at the same time, was "rather nervous and shy," suggesting a "lack of self-confidence." He noted, however, that she certainly had a large number of Soviet contacts, and knew how to meet and talk to people. Jameson indicated at the outset of his report that Priscilla had been "selected as a likely candidate to write an article on Yevtushenko in a major U.S. magazine for our campaign." He recognized that Priscilla was "concerned about making her articles accurate as to fact and free from any external influence," but believed that "she might be worked around to writing an article in which she genuinly (sic) believed, but would also further our purposes for Yevtushenko" (a popular Russian poet).

Much of the report is a summary of Jameson's discussion with Priscilla about various Russian poets and Yevtushenko especially, whom the CIA seemed to be particularly interested in. Priscilla informed Jameson that she had arranged to write several articles for The Reporter - including one on Yevtushenko - and emphasized that "she thought she must write only the truth, without defining exactly what that was to me."

In conclusion, Jameson pointed out that, despite what she had stated: "I think that Miss Johnson can be encouraged to write pretty much the articles we want. It will require a little more contact and discussion, but I think she could come around ... Basically, if approached with sympathy in the cause she considers most vital, I believe she would be interested in helping us in many ways. It would be important to avoid making her think that she was being used as a propaganda tool and expected to write what she is told. I don't think she would go along with that idea at all. On the other hand, she is searching for both more information and more understanding of the problem of the Soviet intellectual and is consequently subject to influence."

It is certainly clear that the CIA intended to make full use of Priscilla Johnson's talents as a Soviet researcher and writer in an ongoing attempt to destabilize conditions in the Soviet Union, apparently without her complete knowledge.

The next document, dated February 5, 1964, and numbered 17458 (suggesting that there might be a document still classified in between), is a lengthy memo based on a meeting with Priscilla on Jan. 30 and 31,1964, this time written by Gary Coit (SR/CA). Although the report was prepared two months after the assassination of JFK, there is no mention of the subject, including Priscilla's revised report of Nov. 24, 1963 about having interviewed Lee Harvey Oswald. However, in the initial four line paragraph, two full lines and a partial line have been blacked out.

Intriguingly, there is a reference to Priscilla having written to "...her former boss, President Kennedy..." in regard to the fact that her notebooks had not been returned to her by the Soviet Union; they had been removed from her luggage as she was leaving Leningrad (Priscilla pointed out that none of the material was "...particularly sensitive ... and would not have really seriously compromised any of her contacts in the USSR.") Presumably, Coit's reference to JFK as Priscilla's "boss" dates back to the mid-1950s when he was a senator. Nevertheless, she was able to obtain the President's assistance, as press secretary Pierre Salinger had made contact with the Soviet Ambassador about her notebooks, "...which produced no result."

The overall purpose of the Jan. 30-31 meetings (which lasted a total of 11 hours) was to "...debrief Johnson on her flaps with the Soviets when she was in the USSR, notably at the time of her last exit." Much of the memo deals with some of the problems Priscilla encountered with Soviet officials related to her visa and attempts to have it extended. She was able to meet with a Soviet lawyer and, later, his boss in the Foreign Office, and was asked to prepare "...a complete curriculum vitae on herself" - which Priscilla refused to produce. She was also asked about certain issues such as NATO and Soviet-American trade, and "...whether or not she would be interested in writing articles for Soviet publications."

An attempt was made during the debriefing to learn about Priscilla's "contacts" while in the USSR, but she was unwilling to provide names (one of her contacts had been exiled for a year); therefore "...no effort was made to attempt to force the issue of a debriefing on her contacts." However, Coit indicated during the interview that he would "...probably be back to see her from time to time to see what she knows about specific persons whose names might come up, and she at least nodded assent to this."

Reference was made to a reporter/translator named Victor Louis associated with both McGraw-Hill and NANA, whom Priscilla felt had a "...lousy reputation in Moscow;" she attempted unsuccessfully to get NANA to "drop Louis." She also encouraged NANA to hire "...Ruth Danilov, the wife of another correspondent" (possibly Victor Danilov, author of Rural Russia: Under the New Regime (Univ. of Indiana Press, 1988), but more likely Nicholas Daniloff, a Newsweek correspondent who wrote Two Lives: One Russia (Avon Publishing, 1990) - Coit might have misspelled Ruth's last name.) However, the Soviets refused to accredit her. Priscilla pointed out that NANA subsequently hired "Dick Steiger" who was immediately accredited, due to his "left wing past." Brief reference was also made to Frieda Lurye, a liberal Russian who had spoken at Harvard, as well as Yelena Romanova, whom Priscilla "thoroughly dislikes and thinks ought to be discredited."

Priscilla raised the question during the interview of the likelihood of being able to return to the Soviet Union as a "correspondent." Coit felt it depended on whether the Soviets believed she could be "...useful for some of their plans." Coit felt that her chances were good, since she had not been in any "...serious trouble or done anything especially bad." However, to the best of my knowledge, Priscilla never again returned to the USSR.

Coit had brought up the name "Alex Dolberg" during the debriefing, whom Priscilla knew and talked to at length when he was "...at Harvard." The CIA were quite certain that he was "...working for Sovs and therefore advised her to be careful in any dealings with him." Priscilla had been equally suspicious, although her discussions with him had "...developed her understanding of the Soviet machine ... and (she) now understands power as used by the Sovs."

In his final paragraph, Coit stated that he was "...vaguely uncomfortable after this long discussion with Johnson...", even though he found her to be "...intelligent and well informed on the Soviet Union" (although with "...an air of naivety and innocence, which is really only a mannerism"). Coit felt that Johnson's interest in the Soviet Union was "...an intellectual thing," and that she was "...not out to destroy the Communist system" (the major goal of the CIA). Having spoken to another U.S. correspondent named Patricia Blake (who later wrote a glowing review of Marina and Lee for Time magazine), Coit had noted two "...apparent contradictions" related to Priscilla:

1) she had defended Dolberg to Blake, who for years she had thought was "...no good;" and

2) according to Blake, Miss Johnson had developed a "...low opinion of Lurye after the Boston press conference," in contrast to comments made by Priscilla during the debriefing.

In conclusion, Coit felt that "...we cannot expect to use Johnson actively in operations. She obviously doesn't want to get involved in deep plots. She is unlikely to be the type of informant who will volunteer information; but she will supply info she has acquired, if asked and if it's not too sensitive, such as the identies (sic) of her friends in the USSR."

There is no indication whether the CIA encouraged Priscilla to contact Marina Oswald through its publishing connections, or whether she provided any feedback based on her extensive interviews later that year, but such information could very well be included in another, still classified document.

The third document that I received, dated February 23, 1965, is also a memo written by Gary Coit, based on a phone call from Priscilla in regard to Alex Dolberg. By now Dolberg was living "...in London's demi-monde with homosexuals, drunks, beatniks, etc." and had become "...terribly paranoid", convinced that he was being "...followed everywhere." Priscilla had heard from several sources that Dolberg might be considering going back to the USSR because of the death of his mother and the condition of his father. Coit indicated that Priscilla had reported this information because of her belief that Dolberg "...could do more harm to followers of Soviet intellectual affairs, both in the West and in the USSR, than anyone else she can think of." They both agreed that "someone" should have a talk with Dolberg, and encourage him to recognize the fact that returning to the USSR would be a mistake. At the same time, Coit felt it was important to emphasize to Dolberg that no one trusted him in the West, believing he was a "...Soviet agent," but if he told the CIA everything he knew, he could be "...rehabilitated" and have his name cleared.

Based on the fact that Priscilla had made the call to the CIA, regardless of her motivation, it would appear that she had become an informer for the Agency, although it is impossible to know how much other information she provided, and whether any of it related to her contact with Marina Oswald.

It should be noted that the CIA's interest in Priscilla Johnson began at an early date, based on the fact that a "201 file" was opened most likely in the mid-1950s(2) and, according to a fourth document declassified in 1993 entitled, "Review of 201 File on U.S. Citizen," Priscilla's file had not been closed as of Jan. 28, 1975. She was listed as a "witting collaborator," although the nature of her collaboration was not described.(3)

In addition to the four documents described above, I also received a copy of Priscilla's HSCA Executive Session interview that took place on April 20,1978, although 40 out of 113 pages of transcript have been withdrawn by the CIA. It was clear that the committee members did not entirely trust her.

(7) Walt Brown, Treachery in Dallas (1995)

While awaiting word of his acceptance into Russian society, Oswald gave two interviews to American journalists in Moscow. Priscilla Johnson would later testify that her interview with Oswald left her with the feeling that "the plight of the U.S. Negro brought him to the USSR."' This is a difficult thesis to reconcile, given Oswald's later relationships with Guy Banister et al. (hardly civil rights fanatics), Oswald's seeming absence of civil rights concerns in the United States (the "Clinton, Louisiana" posturing aside), and finally, what could Oswald possibly do about the plight of the U.S. Negro from far off Russia?

When Aline Mosby interviewed him, she indicated, "Beyond his brown eyes [emphasis added], I felt a certain coldness." She also indicated that some of Oswald's statements sounded rehearsed (a claim that others would make), and she told of Oswald's boast that he saved the $1,500 necessary for the trip. She concluded that she considered defectors to fall generally within one of two categories, but "Oswald appeared to be a one-man third category." Indeed.

Both journalists tended to agree that Oswald was overplaying his "defector" role and that the Soviets wouldn't buy it. Oswald, however, had to go through the ritual, as he had to know, or have been taught, that the Soviets were listening.

To reinforce his credentials, Oswald staged a performance for the benefit of consuls Snyder and McVickar at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, conveniently attempting to renounce his citizenship at a time when the embassy was closed. Documents from this event suggest Oswald would offer secrets, or "has offered"' secrets to the Russians understanding of the problem of the Soviet intellectual and is consequently subject to influence.

(8) John M. Newman, Oswald and the CIA (1995)

Neither Priscilla Johnson's 1959 contemporaneous notes nor her 1963 written recollection mentions that Oswald told her he had threatened to reveal radar secrets. Her book Marina and Lee makes no mention of radar secrets. Her newspaper articles then and since make no mention of radar secrets. Under oath, however, she told a very different story. Here is the bombshell she dropped during her sworn testimony to the Warren Commission:

MR. SLAWSON: Miss Johnson, I wonder if you would search your memory with the help of your notes and make any comments you could on what contacts Lee Oswald had had with Soviet officials before you saw him, any remarks he made or things you could read between the lines, and so on.

MISS JOHNSON: I had the impression, in fact he said, he hoped his experience as a radar operator would make him more desirable to them [the Soviets]. That was the only thing that really showed any lack of integrity in a way about him, a negative thing. That is, he felt he had something he could give them, something that would hurt his country in a way, or could, and that was the one thing that was quite negative, that he was holding out some kind of bait.

In a 1994 interview with the author, Priscilla McMillan found the contradiction between her Warren Commission testimony and other writings troubling. How could Priscilla not have written about such a startling part of her interview with Oswald? "I know, that it is terrible," she remarked in 1994, "that is so unprofessional." Her recollection was at first indecisive, and she wondered if it had not been "wrong to tell the Warren Commission that." At length, however, she stuck with her testimony." Not surprisingly, Priscilla's revelation about radar secrets startled her Warren Commission interrogator, W. David Slawson. This is what happened next:

MR. SLAWSON: Could you elaborate a little bit on that radar point. Had you been informed by the American Embassy at the time that he had told Richard Snyder that he had already volunteered to the Soviet officials that he had been a radar operator in the Marine Corps, and would give the Russian government any secrets he had possessed?

MISS JOHNSON: I had no idea that he had told Snyder that, but he did tell me-I got the impression, I am not sure that it is in the notes or not, l certainly got the impression that he was using his radar training as a come-on to them, hoped that that would make him of some value to them, and I

MR. SLAWSON: This was something then that he must have volunteered to you, because you would not have known to ask about it?

MISS JOHNSON: Well, again I am not very military minded, and I couldn't have cared less, you know. But somehow along the line, if it is not in my notes then it is a memory, then it is one of the things I didn't write-well, one thing is you know I tend to write what I thought I might use in the story. But I wasn't going to write a particularly negative story about him. I wasn't going to write that he was using it as a come-on so I might not have transcribed it simply for that reason, that it wasn't a part of my story. But it definitely was an impression that he-and it was from him, certainly not from the embassy, that he was using that as a come on, and I sure didn't like that. But it didn't occur to me he might have military secrets. I just felt, well hell, he didn't have much as a radar operator that they need, although even there I didn't know. Maybe there was some little twist in our radar technique that he might know. It showed a lack of integrity in his personality, and that I remembered. What he might or might not have to offer them I didn't know.

What emerges from this testimony is that Priscilla was predisposed against doing a critical story on Oswald, so much so that contrary to a reporter's instincts to get the most dramatic story, she deliberately ignored Oswald's stated intent to commit a disloyal act.

(9) Priscilla Johnson McMillan was interviewed by William L. Joyce at the Assassination Records Review Board (24th March, 1995)

William L. Joyce: Ms. McMillan, there have been several statements to the effect that you might have had a connection to the Central Intelligence Agency. I was wondering if you could elucidate the nature of them and whether you might have had any conversations with the CIA concerning Oswald in connection with the Soviet Union or Cuba.

Priscilla Johnson McMillan: Thank you for asking, Mr. Joyce. My government service was 30 days as a translator in Moscow in the winter of -- early 1956, when I was a translator for the Joint Press Reading Service -- American, British, Canadian -- I think there was a fourth country.

It was an English-language translating service, and my boss there asked for my continued employment but was refused, because I did not have a security clearance from the U.S. Government.

My conversations with CIA officials about Oswald came only following the assassination. I think it was the FBI who came to see me over the weekend of November 22nd-23rd. I'm not sure if I ever did talk to CIA people about Oswald after the assassination. I talked to State Department, Warren Commission.

I did have a conversation once in Grand Central Station with a CIA official, and until recently, I couldn't remember why I had that conversation, but I think I do remember now that it was in 1959, before I was returning to the Soviet Union after covering Khrushchev's visit to President Eisenhower in the fall of '59.

I had been under a good deal of pressure from the KGB to be an informer when I was a reporter, and I was frightened in going back, and I thought somebody -- the American ambassador was aware of my difficulties, but I was afraid that something could happen to me, and I wanted someone on the outside to know, and that was the fall of '59.

His name was Gary Coite, and I believe I was asked about that by the House Assassinations Subcommittee, but I am not sure whether I remembered at that time why I spoke with him, and then, in the autumn of '62, Mr. Donald Jamenson, who I thought was named Mr. James McDonald, came to see me in Cambridge, and I spoke to him about my observations on a visit I had just made for The Reporter magazine about the intellectual atmosphere.

I was writing about the de-Stalinization and Soviet painters and writers, and my notes had been confiscated when I left Leningrad airport, 18 notebooks, and President Kennedy had helped me with that matter. That is, Carl Kazen - he had had Kazen speak to me.

And so, I felt that I should speak to Mr. Jamenson, and I did not - my effort then - I assumed that anything one intelligence service knew, the other intelligence service knew and that their files were inter-penetrated - and of course, my concern was for my Soviet friends.

So, I didn't name names except of, I think, Yveta Chenko, people who were so well-known in the west that I couldn't hurt them, but otherwise I gave him the mood - I don't think I mentioned names of anyone I thought could be hurt.

And those were the extent of my witting contacts with the -- I, of course, knew people in the American embassy, the British embassy, the French embassy, and the Israeli embassy, but I only saw them -- contacts about things I was particularly interested in, like the British had someone who knew a lot about the parasite laws passed by Khrushchev in 1959, but the Israelis knew a lot about intellectual circles and so did the French, more than the Americans did, and the Americans I would go to for agriculture and economy.

But if I thought somebody was in the intelligence of either side, I avoided them. It was just a demimonde - and I avoided them, but of course, I would have talked to people that I didn't know, and in that situation, the only thing that saved you and made you able to write and have any spontaneity in your life is to be a somewhat open person, and so, I tried to be like that, but of course, you don't know everything you're dealing with, and it was a rapidly-changing situation.

(10) Lisa Pease, James Earl Ray Did Not Kill MLK (2003)

Another author favored by the intelligence community, was George McMillan, whose book The Making of an Assassin was favorably reviewed by no less than Jeremiah O'Leary. Mark Lane tells us "On November 30, 1973, it was revealed that the CIA had forty full-time news reporters on the CIA payroll as undercover informants, some of them as full-time agents." Lane adds, "It seems clear than an agent-journalist is really an agent, not a journalist." He then tells us: " In 1973, the American press was able to secure just two of the forty names in the CIA file of journalists. The Washington Star and the Washington Post reported that one of the two was Jeremiah O'Leary."

On March 2 of 1997, the Washington Post ran not one but two articles condemning Ray and the calls for a new trial, written by longtime CIA-friendly journalists Richard Billings and Priscilla Johnson McMillan, wife of George

McMillan. In another paper the same Sunday, G. Robert Blakey, the architect of the cover-up at the HSCA, also made his voice heard for the case against a new trial. And a week later, Ramsey Clark - the man who within days of the - assassination was telling us there was no conspiracy in the King killing - had also recommended the formation of yet another government panel in lieu of a trial for Ray. The only voice missing was Gerald Posner. But his too would come. Posner's next book, Killing the Dream, was about the King assassination.

Is the presence of such people commenting on the James Earl Ray case just coincidence? Or is it indicative of a continuing cover-up? Examine their back grounds and decide for yourself.

It's predictable, really, that Priscilla would be writing in defense of the official myths relating to the MLK case. "Scilla," as her husband called her, has been doing the same in the John Kennedy assassination case for years. She just happened to be in the Soviet Union in time to snag an interview with the mysterious Lee Harvey Oswald. Later, she snuggled up to Marina long enough to write a book which Marina later said was full of lies, called Marina and Lee. Priscilla's parents once housed one of the most famous and high-profile defectors the CIA ever had - Svetlana Alliluyeva, daughter of Josef Stalin. Evan Thomas - father of the current Newsweek mogul of the same name and the man who edited William Manchester's defense of the Warren Report - assigned Priscilla to write the defector's biography. Alliluyeva later returned to the Soviet Union in dismay, saying she was under the watch of the CIA at all times.

Is Priscilla CIA? She applied for a job there in the '50s, and her 201 file lists her as a "witting collaborator," meaning, not only was she working with the agency, she knew she was working with the agency. And how independent was she? In a memo from Donald Jameson, who was the Soviet Russia Branch Chief and who in the same year handled CIA Counterintelligence Chief James Angleton's prize (and the CIA's bane) Anatoliy Golitsyn, wrote of Priscilla: "Priscilla Johnson was selected as a likely candidate to write an article on Yevtushenko in a major U.S. magazine for our campaign ... I think that Miss Johnson can be encouraged to write pretty much the articles we want."

(11) Bill Simpich, The Twelve Who Built the Oswald Legend (22 August, 2010)

If you appreciate gazing into the darkness, that's all the more reason to gather around the fire. This is a story about ghosts and spooks that haunt the United States of America. When it's over, I'm going to suggest that we talk to the people in Washington who can help us make sure we can get the end of the story right. Some of the last chapters are written down and sitting in cold, unlit basements. And though this story is filled with ghosts, some of the spooks are still alive and can still talk.

With millions of documents released in the years since the JFK Act was passed in the nineties, the intelligence backgrounds of the twelve who built the Oswald legend have come into focus. A legend maker can range from a "babysitter" who just keeps an eye on the subject to someone handing out unequivocal orders. I count twelve of them, and I'll tell you about them here in this series of essays.

Many of these legend makers did not know each other, and some of them know nothing about the JFK assassination itself, but their stories when put together can solve important puzzles. A couple of them are integral to the plot. Now is the moment to sum up what we have, demand the rest, and ask the right questions to those still alive. Although we may never know who fired the shots at JFK, you may agree that the new documents reveal who called the shots.

Priscilla Mary Post Johnson was identified with a CI/OA (counter-intelligence/operational approval) number in a 1956 CIA application (C-52373) four years after her initial 1952 application.

The response from the Office of Security in 1956 was odd, because it stated that C-52373 was "Priscilla Livingston Johnson", not "Priscilla R", and that "she was apparently born 23 September 1922 in Stockholm, Sweden, rather than 19 July 1928 at Glen Cove, New York."

During the formation of the HSCA, Johnson wanted to review what was in the records. "Priscilla Johnson McMillan aka Priscilla Mary Post Johnson" submitted a sworn FOIA request to the FBI asking for all records "indicating my employment in your agency". This statement revealed not only her previously unknown relationship with the Bureau, but also that the 1928/Glen Cove data is her authentic birthdate and birthplace. Now we have some reliable data on Johnson that should offer light when studying her path.

When Johnson's 1956 application was withdrawn in 1957, the memo from SR/10 contradicted the 1956 application with the claim that the birthdate for C-52373 was 19 July 1928. A game is being played with Johnson's identity and birthdates, a game that continues to this day. It's probably a holding action to protect Johnson's reputation, because her book Marina and Lee is now a central pillar in the continuing political battle about what happened in Dallas that day. (I would agree with Thomas Powers' assessment in the New York Times Book Review that Marina and Lee is a "miraculous book".)

What we do know is that on April 10, 1958, Cord Meyer sent a cable to Western Europe expressing interest in Johnson, right after Johnson applied for a Soviet visa in Paris. A couple weeks later, a request went out seeking approval for Johnson to become a "REDSKIN traveler and informant", and that "SR/2 (Soviet Russia Division #2) will have primary responsibility of handling agent."

Johnson was supposedly rejected in June 1958 because her "past activity in USS4, insistence return and indefinite plans inside likely draw Sov suspicions". Nonetheless, she decided to return to Moscow and study Soviet law under a fellowship grant from either Columbia or Harvard universities. By 1962, she was being vetted by the notorious anti-communist professor Richard Pipes and the CIA's Office of Security for a position in a "Soviet survey".

Other memos, one sent by "SR/RED/O'Connell", illustrate that three Priscillas have now emerged: Besides the original Priscilla Mary Post Johnson, we now also see the names "Priscilla McClure Johnson, Priscilla McCoy" that are not identical with the original. To top it off, if you add in the references to "Priscilla Livingston Johnson" and "Priscilla R. Johnson", there are now five Priscillas competing for space in the same case file.

These five Priscillas are corroborated by the four CI/OA numbers for Priscilla Johnson seen on her "approval work record" form.

After all this smoke and fog, the American public has no reason to assume that the US government has done anything but confuse everyone about the role of Johnson.

I did find what is described as a "true name dossier" in the Office of Security files that lists Priscilla Johnson with the biographical file number 201-102798. Furthermore, the Office of Legal Counsel made it plain that it had reviewed "documents from Priscilla Johnson McMillan's 201 file (201-102798)." By the 1970s, Priscilla Johnson McMillan was her married name. We can see with our own eyes that a close-out document for the CIA's 201-102798 file describes "Johnson" as a "witting collaborator" in 1975.

Is it any surprise that Johnson responded in an interview with Anthony Summers and his wife Robbyn that "the Johnson in the 1975 document is someone other than herself?"

Under her married name of Priscilla Johnson McMillan, she muddied the waters further by releasing her book Marina and Lee - after fourteen years of writing and re-writing - in the midst of the reopened investigation of the JFK case by the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978.

This exercise in game-playing will probably continue with the CIA refusing to reveal Johnson's files until after her death. Johnson could easily resolve these questions by releasing her own copies of the files to the public - and by squarely addressing further questions while she is still alive....

At this point, Johnson had been accepted by the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA) in Moscow. For good reasons, NANA has a bad reputation as a hotbed of intelligence.

Ernest Cuneo purchased NANA in the mid-1950s and was its owner and president until 1963. Cuneo started out as an aide to a World War I veteran, New York progressive mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who served in World War I. Cuneo served with the OSS during World War II and was its liaison to the White House, State Department, FBI, and British intelligence. NANA's vice president was the well-known author Ian Fleming. Fleming later credited Cuneo with more than half the plot for Goldfinger and all of the basic plot for Thunderball. The dedication page in Goldfinger reads, "To Ernest Cuneo, Muse."

(12) The Valley News (22nd November, 2013)

McMillan grew up in the New York City area and went to Bryn Mawr College, where she studied Russian. She went on to get a master's degree in Soviet Studies from Radcliffe College in 1952. Eager to put her Russian to use, she had gotten a tourist visa to the U.S.S.R. in December 1955, going by rail. "I loved being on the train from Helsinki through to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). I loved the fir trees and the snow and I think I had a great sense of anticipation," she said. In the back of her mind was Lenin's famous journey in a closed train to the Finland Station in St. Petersburg when he returned from exile in Switzerland in 1917.

She managed, perhaps through sheer ignorance of the fact that she shouldn't do these things, to infiltrate parts of Soviet society where you wouldn't assume a young American woman would necessarily go on her own during the Cold War. She observed the Soviet court system and a class at Moscow University in Soviet literature taught by one S.I. Stalin, Svetlana Stalin, Joseph's daughter, but such excursions were infrequent..