On this day on 16th January

On this day in 1806 William Pitt the Younger died. William Pitt was born at Hayes, Kent on 28th May 1759. He suffered from poor health and was educated at home. His father, William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, was the former M.P. for Old Sarum and one of the most important politicians of the period. The Earl of Chatham was determined that his son would eventually become a member of the House of Commons and at an early age William was given lessons on how to become an effective orator.

When William was fourteen he was sent to Pembroke Hall, Cambridge. His health remained poor and he spent most of the time with his tutor, the Rev. George Pretyman. William, who studied Latin and Greek, received his M.A. in 1776.

William grew up with a strong interest in politics and spent much of his spare time watching debates in parliament. On 7th April 1778 he was present when his father collapsed while making a speech in the House of Lords and helped to carry his dying father from the chamber.

In 1781 Sir James Lowther arranged for William Pitt to become the M.P. for Appleby. He made his first speech in the House of Commons on 26th February, 1781. William Pitt had been well trained and afterwards, Lord North, the prime minister, described it as the "best speech" that he had ever heard.

Soon after entering the Commons, William Pitt came under the influence of Charles Fox, Britain's leading Whig politician. Pitt joined Fox in his campaign for peace with the American colonies. On 12th June he made a speech where Pitt insisted that this was an "unjust war" and urged Lord North's government to bring it to an end.

Pitt also took an interest in the way that Britain elected Members of Parliament. He was especially critical of the way that the monarchy used the system to influence those in Parliament. Pitt argued that parliamentary reform was necessary for the preservation of liberty. In June 1782 Pitt supported a motion for shortening the duration of parliament and for measures that would reduce the chances of government ministers being bribed. When Lord Frederick North's government fell in March 1782, Charles Fox became Foreign Secretary in Rockingham's Whig government. Fox left the government in July 1782, as he was unwilling to serve under the new prime minister, Lord Sherburne. Short of people willing to serve him, Sherburne appointed the twenty-three year old Pitt as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Fox interpreted Pitt's acceptance of this post as a betrayal and after this the two men became bitter enemies.

On the 31st March, 1783, Pitt resigned and declared that he was "unconnected with any party whatever". Now out of power, Pitt turned his attention once more to parliamentary reform. On 7th May he proposed a plan that included: (1) checking bribery at elections; (2) disfranchising corrupt constituencies; (3) adding to the number of members for London. His proposals were defeated by 293 to 149. Another bill that he introduced on 2nd June for restricting abuses in public office was passed by the House of Commons but rejected by the House of Lords.

In Parliament he opposed Charles Fox's India Bill. Fox responded by making fun of Pitt's youth and inexperience and accusing him of following "the headlong course of ambition". George III was furious when the India Bill was passed by the House of Commons. The king warned members of the House of Lords that he would regard any one who voted for the bill as his enemy. Unwilling to upset the king, the Lords rejected the bill by 95 votes to 76.

The Duke of Portland's administration resigned and on 19th December, 1783, the king invited William Pitt to form a new government. At the age of only twenty-four, Pitt became Britain's youngest prime minister. When it was announced that Pitt had accepted the king's invitation, the news was received in the House of Commons with derisive laughter.

Pitt had great difficulty finding enough people to join his government. Except for himself, his cabinet of seven contained no members of the House of Commons. Charles Fox led the attack on Pitt and although defeated in votes several times in the Commons, he refused to resign. After building up his popularity in the country, Pitt called a general election on 24th March, 1784. Pitt's timing was perfect and 160 of Fox's supporters were defeated at the polls. Pitt himself stood for the seat of Cambridge University.

Pitt now had a majority in the House of Commons and was able to persuade parliament to pass a series of measures including the India Act that established dual control of the East India Company. Pitt also attacked the serious problem of smuggling by reducing duties on those goods that were mainly being imported illegally into Britain. The success of this measure established his reputation as a shrewd politician.

In April 1785 Pitt proposed a bill that would bring an end to thirty-six rotten boroughs and to transfer the seventy-two seats to those areas where the population was growing. Although Pitt spoke in favour of reform, he refused to warn the House of Commons that he would resign if the measure was defeated. The Commons came to the conclusion that Pitt did not feel strongly about reform and when the vote was taken it was defeated by 248 votes to 174. Pitt accepted the decision of the Commons and never made another attempt to introduce parliamentary reform.

The general election of October 1790 gave Pitt's government an increased majority. For the next few years Pitt was occupied with Britain's relationship with France. Pitt had initially viewed the French Revolution as a domestic issue which did not concern Britain. However, Pitt became worried when parliamentary reform groups in Britain appeared to be in contact with French revolutionaries. Pitt responded by issuing a proclamation against seditious writings.

When Pitt heard that King Louis XVI had been executed in January 1793, he expelled the French Ambassador. In the House of Common's Charles Fox and his small group of supporters attacked Pitt for not doing enough to preserve peace with France. Fox therefore blamed Pitt when France declared war on Britain on 1st February, 1793.

Pitt's attitude towards political reform changed dramatically after war was declared. In May 1793 Pitt brought in a bill suspending Habeas Corpus. Although denounced by Charles Fox and his supporters, the bill was passed by the House of Commons in twenty-four hours. Those advocating parliamentary reform were arrested and charged with sedition. Tom Paine managed to escape but others such as Thomas Hardy, John Thellwall and Thomas Muir were imprisoned.

Pitt decided to form a great European coalition against France and between March and October 1793 he concluded alliances with Russia, Prussia, Austria, Spain, Portugal and some German princes. At first these tactics were successful but during 1794 Britain and her allies suffered a series of defeats. To pay for the war, Pitt was forced to increase taxation and to raise a loan of £18 million. This problem was made worse by a series of bad harvests. When going to open parliament in October 1795, George III was greeted with cries of 'Bread', 'Peace' and 'no Pitt'. Missiles were also thrown and so Pitt immediately decided to pass a new Sedition Bill that redefined the law of treason.

Britain's continuing financial difficulties convinced Pitt to seek peace with France. These peace proposals were rejected by the French in May 1796 and William Pitt once again had to introduce new taxes. This included duties on horses and tobacco. The following year Pitt introduced additional taxes on tea, sugar and spirits. Even so, by November 1797, Britain had a budget deficit of £22 million. On several occasions Pitt was in physical danger from angry mobs and he had to be constantly protected by an armed guard. Pitt's health began to deteriorate and newspapers began reporting that the prime minister had suffered a mental breakdown and was insane. Pitt responded by passing new laws that enabled the government to suppress and regulate newspapers.

Britain's financial problems continued and in his budget of December 1798 William Pitt introduced a new graduated income tax. Beginning with a 120th tax on incomes of £60 and rising by degrees until it reached 10% on incomes of over £200. Pitt believed that this income tax would raise £10 million but in fact in 1799 the yield was just over £6 million.

In 1797 Pitt appointed Lord Castlereagh as his Irish chief secretary. This was a time of great turmoil in Ireland and in the following year Castlereagh played an important role in crushing the Irish uprising. Castlereagh and Pitt became convinced that the best way of dealing with the religious conflicts in Ireland was to unite the country with the rest of Britain under a single Parliament. The policy was unpopular with the borough proprietors and the members of the Irish Parliament who had spent large sums of money purchasing their seats. Castlereagh appealed to the Catholic majority and made it clear that after the Act of Union the government would grant them legal equality with the Protestant minority. After the government paid compensation to the borough proprietors and promising pensions, official posts and titles to members of the Irish Parliament, the Act of Union was passed in 1801.

George III disagreed with Pitt and Castlereagh's policy of Catholic Emancipation. When Pitt discovered that the king had approached Henry Addington to become his prime minister, he resigned from office. Although Pitt had been paid £10,500 a year as prime minister, he was now deeply in debt and for a while he feared that he would be declared bankrupt. A group of friends agreed to help but it was only after selling his family home that he was able to satisfy his creditors.

In May 1804 Henry Addington resigned from office and once again William Pitt became prime minister. Lord Castlereagh was appointed Secretary for War but many leading politicians, including Charles Fox, refused to serve under Pitt. Out of the twelve man cabinet, only Pitt and Castlereagh were from the House of Commons.

With Napoleon planning to invade England, Pitt quickly formed a new coalition with Russia, Austria and Sweden. When the French were defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805, Pitt was hailed as the savior of Europe. However, Napoleon fought back and in December, 1805 he triumphed over the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz.

Pitt was devastated by the news of Napoleon's victory and soon after was taken seriously ill. William Pitt died on 16th January, 1806. He was so heavily in debt that the House of Commons had to raise £40,000 to pay off his creditors.

On this day in 1855 Eleanor Marx, the youngest daughter of Karl Marx, was born in London on 16th January 1855. A very intelligent child, she was mainly taught by her father and by the age of three she could recite passages by Shakespeare. Marx, who treated his daughter as a "friend and companion" could converse with her as a child in German and French as well as English. By the time Eleanor was sixteen (1871) she acted as her father's secretary, accompanying him to international conferences on socialism.

When seventeen Eleanor fell in love with a French journalist, Hippolyte Lissagaray. Although Lissagaray and Marx shared the same political views, he disapproved of the relationship because at 34, Lissagaray was twice the age of his daughter.

To emphasize her independence, Eleanor left the family home and found work as a schoolteacher in Brighton. After a year in Brighton she joined up with Hippolyte Lissagaray and helped him write the History of the Commune of 1871. Although Karl Marx liked the book enough to translate it into English, he still refused to give his approval to his daughter's relationship with Lissagaray. In 1876 Eleanor Marx became involved in the campaign for female equality when she helped a female candidate win a seat on a London School Board.

In 1880 Karl Marx now gave Eleanor permission to marry Hippolyte Lissagaray. However, Eleanor was now having doubts about the relationship and in January 1882, Eleanor terminated her long engagement with Lissagaray.

In the early 1880s Eleanor nursed her aging parents. Her mother died in December, 1881, and her father in March, 1883. Before his death, Karl Marx had given Eleanor the task of preparing his unfinished manuscripts for publication. Eleanor also had the task of dealing with the English publication of Das Kapital .

In 1884 Eleanor became involved with Edward Aveling. The two shared the same views on politics and religion and Aveling made his living from giving lectures on these subjects. As Aveling was already married, Eleanor lived with him as his common law wife.

Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling joined Hyndman's Social Democratic Federation. Eleanor became a close friend of another member of the SDF, Annie Besant. Eleanor Marx, who had a reputation as one of the best orators in England, was elected to the SDF Executive.

Eleanor disagreed with the dictatorial way H. M. Hyndman was running the SDF and in December 1884 joined with William Morris to form the Socialist League. Eleanor now openly advocated "Revolutionary International Socialism" and in 1885 helped organize the International Socialist Congress in Paris. Eleanor also made a successful speaking tour with Aveling of the United States.

In 1886 Eleanor met Clementina Black and began working with her in the Women's Trade Union League. She also helped Annie Besant in her successful Bryant & May match-girl strike. The following year Eleanor helped Will Thorne to organize the National Union of Gas Workers and General Labourers and in 1889 became involved in the Docker's Strike led by her close friend, Ben Tillet.

In 1880s Eleanor took a close interest in the theatre and for a time considered a career in acting. Like Elizabeth Robins, Eleanor was a strong advocate of the plays of Henrik Ibsen. Eleanor believed that the theatre could play an important role in rejecting the traditional views of love and marriage and as a means of propagating socialism.

Eleanor wrote several books and articles including The Factory Hell (1885), The Women Question (1886), The Working Class Movements in America (1888), Shelley's Socialism (1888), and the The Working Class Movement in England (1896). She also contributed many articles for Justice, the political journal edited by H. H. Champion.

In January 1898, Edward Aveling became seriously ill, and Eleanor spent many months nursing him back to health. Soon afterwards she discovered that Aveling had secretly married another woman. Unable to bear the pain of this latest betrayal, Eleanor Marx committed suicide on 31st March, 1898.

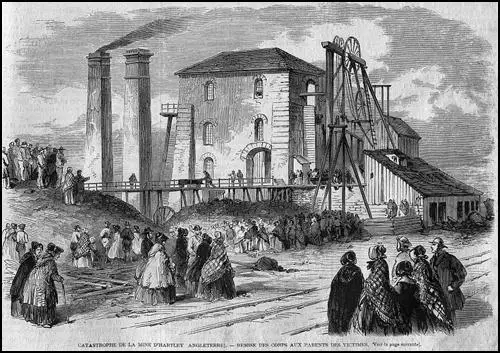

On this day in 1862 – 204 men and boys were killed at Hartley Colliery. During the early stages of the industrial revolution, coal-mining techniques remained primitive and unmechanized. Hewers hacked out the coal from the seams with their picks at the coal face. Putters supplied the face workers with empty tubs and then pushed the full ones from the coal face to the wagons for hauling to the shaft. As a result of the needs of industry, the output of coal between 1830 and 1850 trebled from 15 million tons to 49 million tons.

In 1842 colliers formed the Miners Association of Great Britain and Ireland. Certain areas such as Yorkshire and East Midlands failed to join and the mass importation of strike-breakers during industrial disputes continued to undermine local unions.It is estimated that by 1851 the industry employed 216,000.

The Miners Association campaigned against dangerous working conditions. Accidents in shafts caused by rope and chain breakages, flooding, fires and roof falls continued to kill large numbers of miners. Official statistics were not kept, and powerful colliery owners were often successful at persuading local newspapers not to report the deaths of coal-miners.

By studying all the statistics that are available, one historian has calculated in some collieries in the 19th century, workers had a 50% chance of being killed in a mining accident. One of the worst mining disaster was at the Hartley Colliery, near Seaton Delaval, on 16th January 1862, when 204 men were killed when the beam of the pit's pumping engine broke and fell down the shaft, trapping the men below.

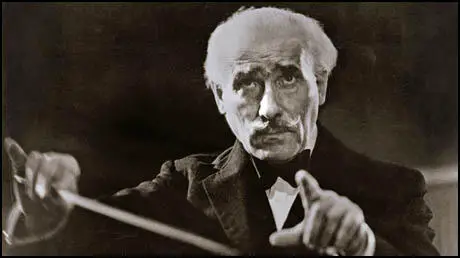

On this day in 1867 Arturo Toscanini, the son of a tailor, was born in Parma, Italy. He studied at the conservatories of Parma and Milan before becoming a cellist.

Toscanini joined an Italian opera company and while performing Aida in Rio de Janeiro in 1886 the conductor was booed. Although only nineteen years of age, Toscanini took over the rostrum and had his first experience as conductor.

Toscanini continued to conduct and in 1891 he opened the season at the Carlo Felice and by 1898 was musical director of La Scala in Milan. He became the world's most famous conductor and was employed by the Metropolitan Opera House in New York (1908-1915) before returning to La Scala.

In Italy Toscanini was a leading critic of the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini. He refused to include the Fascist hymn, Giovinezza, in his concerts and while in Bologna in 1930 he was beaten up by a group of Mussolini's supporters. This failed to stop Toscanini expressing his views on politics and remained in Italy until it became clear that fascism was not going to be removed by logical debate.

In 1938 Toscanini went to live in the United States. Over the next twenty years he conducted the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra and created the National Broadcasting Orchestra of America.

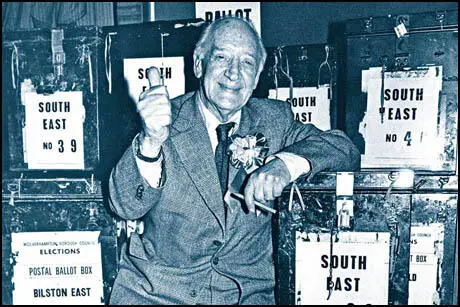

On this day in 1906 Bob Edwards, the son of a docker, was born in Liverpool. He was educated at local schools and as a young man joined the Guild of Youth, an organisation founded by the Independent Labour Party. He was a member of the delegation that visited the Soviet Union that met Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov and Leon Trotsky.

In 1932 he was elected to the Liverpool City Council. Two years later he helped organize the Lancashire Hunger Marchers. He remained in the ILP and in 1935 he unsuccessfully contested Chorley.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Edwards asked members of the Independent Labour Party to volunteer to join the International Brigades. Stafford Cottman was one of the men who offered his services: "I was asked to go along to their headquarters and I met Bob Edwards was its leader.... At headquarters we were all interviewed by Bob and a couple of others. They asked you simple things like why you wanted to go to Spain. The idea was to find out whether you did have a sort of principle or whether it was pure adventure."

Edwards arrived on the Aragón Front in 1936. Other members of the group included George Orwell and Bob Smillie. These men served alongside POUM forces and its leader, Georges Kopp later commented: "We have had a complete success, which is largely due to the courage and discipline of the English comrades who were in charge of assaulting the principal of the enemy's parapets."

Edwards was appointed as a captain in the battalion. He later recalled: "We spent much of our time training members of the Spanish Militia how to take cover and we were constantly trying to persuade them that to walk upright and bravely into an offensive was not necessarily the best method." He added: "The Spanish Civil War, if properly supported, would have been the first defeat of fascism and we very nearly won that war. In the early months of the war, we were winning easily. We attacked Saragossa and could have taken it, but we had a shortage of ammunition and supplies. We released prisoners from the heart of the town. We had the men but not the equipment, and that was true throughout the whole of the war."

Edwards served with Bob Smillie on the front. "His lilting Scottish melodies could often be heard enlivening many difficult and monotonous hours. I can hear his voice now as he shouted slogans in Spanish from our trenches in the Aragon mountains across to the enemy lines. Was it merely coincidence that at this period 100 Spanish workers deserted from Franco?"

According to Gordon Brown: "Bob Edwards was acting as an intermediary for the Spanish Government and managed to negotiate a deal with a British shipowner to arrange the shipment of food supplies. Edwards bought the boat, promising that the Spanish Government would pay up when it reached France."

At the end of April 1937 the Independent Labour Party contingent travelled to Barcelona for a period of leave. Bob Smillie was then given a permission document from a POUM official allowing him to go to a International Bureau meeting in Paris and a speaking tour of Scotland. When he got to Figueras he was arrested by police under the control of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE).

David Murray, the Independent Labour Party representative in Spain, later recalled: "Unfortunately, young Smillie was arrested at the exact time of the crisis in the Valencia government, and no definite steps could be taken to have him released during the period of flux." As Daniel Gray, the author of Homage to Caledonia (2008), has pointed out: "It was clear that Smillie had become a victim of the government's POUM clampdown."

Bob Smillie was charged with carrying "materials of war" (two discharged grenades intended as war souvenirs). He was taken to a prison in Valencia where he talked himself into a further, more serious charge of "rebellion against the authorities". POUM lobbied for the release of Smillie. So did Bob Edwards, James Maxton, Fenner Brockway, and other leaders of the Independent Labour Party.

The authorities in Valencia refused to release Smillie. On 4th June 1937 Smillie began complaining of stomach pains. He was eventually diagnosed with appendicitis. He was taken to hospital but was not operated on because of "ward congestion". On 12th June he was finally examined by a doctor, who came to the conclusion that "owing to congestion in his lower abdomen, he could not be operated upon". Bob Smillie died later that day from peritonitis.

Bob Edwards returned to England in 1938. He later recalled: "I saw enough blood in the Spanish Civil War to last me all my life. Millions died in three years... Returning to England, I thought a world war was inevitable. In 1939 I went to America to help the trade union movement... I came back to England because I could see war was coming. I linked up again with the Chemical Workers Union. I wasn't eligible to be called up because I had been an officer in a foreign army. They wouldn't have had me.''

In 1943 Edwards became National Chairman of the Independent Labour Party. In the 1945 he was defeated by Ronald Bell, the Conservative Party candidate, in the Newport by-election. After the publication of Chemicals: Servant or Master? he was elected as the General Secretary of the Chemical Workers Union in 1947.

Edwards became the Labour Party candidate for Bilston and won the seat in the 1955 General Election. In 1961 Edwards published A Study of a Master Spy, a book about Allen Dulles.

He was appointed as leader of Parliamentary Delegation North Atlantic Assembly 1968-70. In 1974 he became the MP for Wolverhampton South East. In 1983 he became the oldest member sitting in the House of Commons. Bob Edwards, who stood down in 1987, died on 4th June, 1990.

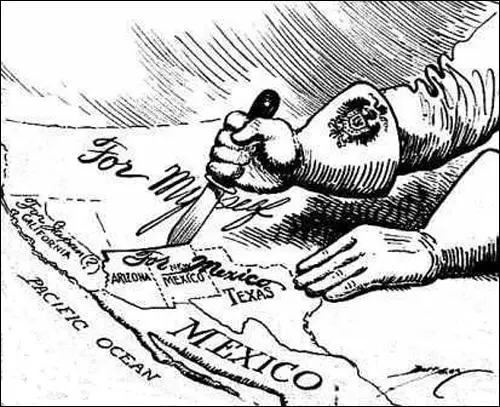

On this day in 1917, the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a coded telegram to the ambassador in Mexico City. In the telegram Zimmermann informed him that Germany intended to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on 1st February. He also instructed the ambassador to propose an alliance with Mexico if war broke out between Germany and the United States. In return, the telegram proposed that Germany and Japan would help Mexico regain the territories that it lost to the United States in 1848 (Texas, New Mexico and Arizona).

On the outbreak of the First World War the Admiralty established the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). People such as Alastair Denniston, Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Frank Birch were involved in intercepting, decrypting, and interpreting naval staff German and other enemy wireless and cable communications. GCCS obtained a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram and after it was decrypted it was passed to the American government.

When he received details of the telegram, President Woodrow Wilson did not immediately declare war and instead commented, "We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with them. We shall not believe they are hostile to us unless or until we are obliged to believe it".

On 21st March the United States tanker, The Healdton, was sunk by a German submarine while in a specially declared "safety zone" in Dutch waters. Twenty American crewmen were killed. Wilson called a meeting with his Cabinet and it unanimously decided to go to war. On 2nd April, President Wilson asked for permission to go to war. This was approved in the Senate on 4th April by 82 votes to 6, and two days later, in the House of Representatives, by 373 to 50. Still avoiding alliances, war was declared against the German government (rather than its subjects).

On this day in 1994 Leland Stowe died. Stowe was born in Southbury, United States, on 10th November, 1899. After graduating from Wesleyan University in 1921, Stowe began work on the Worcester Telegram. The following year he joined the New York Tribune and in 1926 became one of the paper's foreign correspondents. Based in France, Stowe won a Pulitzer Prize in 1930 for his coverage of the Paris Reparations Conference.

In the summer of 1933 Stowe visited Nazi Germany. He was shocked by what he discovered and wrote a series of articles where he argued that Adolf Hitler would over the next few years would attempt to take control of "Austria and large slices of Central Europe". Stowe warned that within ten years Europe would be engulfed in a conflict that would be as bad as the First World War.

The editor of the New York Tribune considered the articles too alarmist and decided not to publish them. Stowe was determined to reveal what was going on in Germany and published the articles in book form under the title Nazi Germany Means War (1933). Only a couple of newspapers and magazines reviewed the book and it sold badly in both Britain and the United States.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Stowe's newspaper told him he was too old to serve as a war correspondent. As he was only 39 he was able to persuade the Chicago Daily News and the New York Post to employ him. Over the next six years he reported the war from forty-four countries on four continents. It is claimed that Stowe's articles in Norway in May 1940 helped force Neville Chamberlain from office as prime minister.

After the war Stowe was foreign editor of Reporter magazine and director of Radio Free Europe's News and Information Service. In 1955 he began teaching at the University of Michigan and also worked as a staff writer for the Reader's Digest.