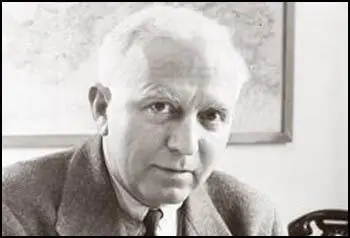

Leland Stowe

Leland Stowe was born in Southbury, United States, on 10th November, 1899. After graduating from Wesleyan University in 1921, Stowe began work on the Worcester Telegram. The following year he joined the New York Tribune and in 1926 became one of the paper's foreign correspondents. Based in France, Stowe won a Pulitzer Prize in 1930 for his coverage of the Paris Reparations Conference.

In the summer of 1933 Stowe visited Nazi Germany. He was shocked by what he discovered and wrote a series of articles where he argued that Adolf Hitler would over the next few years would attempt to take control of "Austria and large slices of Central Europe". Stowe warned that within ten years Europe would be engulfed in a conflict that would be as bad as the First World War.

The editor of the New York Tribune considered the articles too alarmist and decided not to publish them. Stowe was determined to reveal what was going on in Germany and published the articles in book form under the title Nazi Germany Means War (1933). Only a couple of newspapers and magazines reviewed the book and it sold badly in both Britain and the United States.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Stowe's newspaper told him he was too old to serve as a war correspondent. As he was only 39 he was able to persuade the Chicago Daily News and the New York Post to employ him. Over the next six years he reported the war from forty-four countries on four continents. It is claimed that Stowe's articles in Norway in May 1940 helped force Neville Chamberlain from office as prime minister.

After the war Stowe was foreign editor of Reporter magazine and director of Radio Free Europe's News and Information Service. In 1955 he began teaching at the University of Michigan and also worked as a staff writer for the Reader's Digest.

Leland Stowe died on 16th January, 1994.

Primary Sources

(1) Leland Stowe, New York Post (26th April 1940)

Here is the first and only eyewitness report on the opening chapter of the British expeditionary troops' advance in Norway north of Trondheim. It is a bitterly disillusioning and almost unbelievable story.

The British force which was supposed to sweep down from Namsos consisted of one battalion of Territorials and one battalion of the King's Own Royal Light Infantry. These totaled fewer than 1,500 men. They were dumped into Norway's deep snows and quagmires of April slush without a single anti-aircraft gun, without one squadron of supporting airplanes, without a single piece of field artillery.

They were thrown into the snows and mud of 63 degrees north latitude to fight crack German regulars - most of them veterans of the Polish invasion - and to face the most destructive of modern weapons. The great majority of these young Britishers averaged only one year of military service. They have already paid a heavy price for a major military blunder which was not committed by their immediate command, but in London.

Unless they receive large supplies of anti-air guns and adequate reinforcements within a very few days, the remains of these two British battalions will be cut to ribbons.

Here is the astonishing story of what has happened to the gallant little handful of British expeditionaries above Trondheim: After only four days of fighting, nearly half of this initial BEF contingent has been knocked out - either killed, wounded or captured. On Monday, these comparatively inexperienced and incredibly under-armed British troops were decisively defeated. They were driven back in precipitate disorder from Vist, three miles south of the bomb-ravaged town of Steinkjer.

(2) The University Record (24th January, 1994)

Reporting for the Chicago Daily News, and later ABC, he covered the Russian invasion of Finland; revealed the collaboration of Norwegian Vidkun Quisling in helping the Nazis seize Oslo without a shot; recounted the British debacle at Trondheim, Norway, which helped to weaken the government of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain; witnessed other German conquests in the Balkans; uncovered the scheme of Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek to use U.S. military supplies against Chinese Communists rather than the Japanese; reported how the Greeks drove Mussolini’s troops back into Albania, only to fall to Germany; and covered the Russian army from combat zones not accessible to journalists.

In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, Stowe’s honors included the Sigma Delta Chi medallion and award for Norway reporting in 1940; the University of Missouri Medal for outstanding foreign correspondence in 1941; France’s Legion of Honor; the Military Cross of Greece; honorary M.A. from Harvard University; honorary M.A. and LL.D. and the James L. McConaughty Award from Wesleyan University; and LL.D. from Hobart College.