On this day on 9th July

On this day in 1540 Henry VIII of England annuls his marriage to Anne of Cleves. After the death of Jane Seymour in October 1537, Henry VIII had shown little interest in finding a fourth wife. One of the reasons is that he was suffering from impotence. Anne Boleyn had complained about this problem to George Boleyn as early as 1533. His general health was also poor and he was probably suffering from diabetes and Cushings Syndrome. Now in his late 40s he was also obese. His armour from that period reveals that he measured 48 inches around the middle.

However, when Thomas Cromwell told him that he should consider finding another wife for diplomatic reasons, Henry agreed. "Suffering from intermittent and unsatisfied lust, and keenly aware of his advancing age and corpulence" he thought that a new young woman in his life might bring back the vitality of his youth. As Antonia Fraser has pointed out: "In 1538 Henry VIII wanted - no, he expected - to be diverted, entertained and excited. It would be the responsibility of his wife to see that he felt like playing the cavalier and indulging in such amorous gallantries as had amused him in the past."

Thomas Cromwell suggested the name of Anne of Cleves, the daughter of John III. He thought this would make it possible to form an alliance with the Protestants in Saxony. An alliance with the non-aligned north European states would be undeniably valuable, especially as Charles V of Spain and François I of France had signed a new treaty on 12th January 1539. (10) As David Loades has pointed out: "Cleves was a significant complex of territories, strategically well placed on the lower Rhine. In the early fifteenth century it had absorbed the neighbouring country of Mark, and in 1521 the marriage of Duke John III had amalgamated Cleves-Mark with Julich-Berg to create a state with considerable resources... Thomas Cromwell was the main promoter of the scheme, and with his eye firmly on England's international position, its attractions became greater with every month that passed."

John III died on 6th February, 1539. He was replaced by Anne's brother, Duke William. In March, Nicholas Wotton, began the negotiations at Cleves. He reported to Thomas Cromwell that "she (Anne of Cleves) occupieth her time most with the needle... She can read and write her own language but of French, Latin or other language she hath none... she cannot sing, nor play any instrument, for they take it here in Germany for a rebuke and an occasion of lightness that great ladies should be learned or have any knowledge of music."

Cromwell was desperate for the marriage to take place but was aware that Wotton's reported revealed some serious problems. The couple did not share a common language. Henry VIII could speak in English, French and Latin but not in German. Wotton also pointed out that she "had none of the social skills so prized at the English court: she could not play a musical instrument or sing - she came from a culture that looked down on the lavish celebrations and light-heartedness that were an integral part of King Henry's court".

Wotton was frustrated by the stalling tactics of William. Eventually he signed a treaty in which the Duke granted Anne a dowry of 100,000 gold florins. However, Henry refused to marry Anne until he had seen a picture of her. Hans Holbein arrived in April and requested permission to paint Anne's portrait. The 23-year-old William, held Puritan views and had strong ideas about feminine modesty and insisted that his sister covered up her face and body in the company of men. He refused to allow her to be painted by Holbein. After a couple of days he said he was willing to have his sister painted but only by his own court painter, Lucas Cranach.

Henry was unwilling to accept this plan as he did not trust Cranach to produce an accurate portrait. Further negotiations took place and Henry suggested he would be willing to marry Anne without a dowry if her portrait, painted by Holbein pleased him. Duke William was short of money and agreed that Holbein should paint her picture. He painted her portrait on parchment, to make it easier to transport in back to England. Nicholas Wotton, Henry's envoy watched the portrait being painted and claimed that it was an accurate representation.

Holbein's biographer, Derek Wilson, argues that he was in a very difficult position. He wanted to please Thomas Cromwell but did not want to upset Henry VIII: "If ever the artist was nervous about the reception of a portrait he must have been particularly anxious about this one... He had to do what he could to sound a note of caution. That meant that he was obliged to express his doubts in the painting. If we study the portrait of Anne of Cleves we are struck by an oddity of composition.... Everything in it is perfectly balanced: it might almost be a study in symmetry - except for the jewelled bands on Anne's skirt. The one on her left is not complemented by another on the right. Furthermore, her right hand and the fall of her left under-sleeve draw attention to the discrepancy. This sends a signal to the viewer that, despite the elaborateness of the costume, there is something amiss, a certain clumsiness... Holbein intended giving the broadest hint he dared to the king. Henry would not ask his opinion about his intended bride, and the painter certainly could not venture it. Therefore he communicated unpalatable truth through his art. He could do no more."

Unfortunately, Henry VIII did not understand this coded message. As Alison Weir, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) has pointed out, the painting convinced Henry to marry Anne. "Anne smiles out demurely from an ivory frame carved to resemble a Tudor rose. Her complexion is clear, her gaze steady, her face delicately attractive. She wears a head-dress in the Dutch style which conceals her hair, and a gown with a heavily bejewelled bodice. Everything about Anne's portrait proclaimed her dignity, breeding and virtue, and when Henry VIII saw it, he made up his mind at once that this was the woman he wanted to marry."

Anne of Cleves arrived at Dover on 27th December 1539. She was taken to Rochester Castle and on 1st January, Sir Anthony Browne, Henry's Master of the Horse, arrived from London. At the time Anne was watching bull-baiting from the window. He later recalled that the moment he saw Anne he was "struck with dismay". Henry arrived at the same time but was in disguise. He was also very disappointed and retreated into another room. According to Thomas Wriothesley when Henry reappeared they "talked lovingly together". However, afterwards he was heard to say, "I like her not".

The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, described Anne as looking about thirty (she was in fact twenty-four), tall and thin, of middling beauty, with a determined and resolute countenance". He also commented that her face was "pitted with the smallpox" and although he admitted there was some show of vivacity in her expression, he considered it "insufficient to counterbalance her want of beauty". Antonia Fraser has argued that Holbein's painting was indeed accurate and Henry's reaction is best explained by the nature of erotic attraction. "The King had been expecting a lovely young bride, and the delay had merely contributed to his desire. He saw someone who, to put it crudely, aroused in him no erotic excitement whatsoever."

Henry VIII asked Thomas Cromwell to cancel the wedding treaty. He replied that this would cause serious political problems. Henry married Anne of Cleves on 6th January 1540. He complained bitterly about his wedding night. Henry told Thomas Heneage that he disliked the "looseness of her breasts" and was not able to do "what a man should do to his wife". Henry later claimed that he doubted Anne's virginity, because she had the fuller figure that he expected a married woman to have, rather than the slimmer one of a maiden.

Two of her ladies-in-waiting, Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford and Eleanor Manners, Countess of Rutland, asked Anne about her relationship with her husband. It became clear that she had not received any sex education. "When the King comes to bed he kisses me and taketh me by the hand, and biddeth me good night... In the morning he kisses me, and biddeth me, farewell. Is not this enough?" She enquired innocently." Further questioning revealled that she was completely unaware of what had been expected of her.

Henry VIII was angry with Thomas Cromwell for arranging the marriage with Anne of Cleves. The conservatives, led by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, saw this as an opportunity to remove him from power. Gardiner considered Cromwell a heretic for introducing the Bible in the native tongue. He also opposed the way Cromwell had attacked the monasteries and the religious shrines. Gardiner pointed out to the King that it was Cromwell who had allowed radical preachers such as Robert Barnes to return to England. The French ambassador reported on 10th April, 1540, that Cromwell was "tottering" and began speculating about who would succeed to his offices. Although he resigned the duties of the secretaryship to his protégés Ralph Sadler and Thomas Wriothesley he did not lose his power and on 18th April the King granted him the earldom of Essex.

In the spring of 1540 Henry VIII met Catherine Howard who had joined the household which had been set up for Queen Anne of Cleves. (25) Alison Weir pointed out that at this time Henry was not in good health: "It had already therefore occurred to her that she might become queen of England, and this was no doubt enough to compensate for the fact that, as a man, Henry had very little to offer a girl of her age. He was now nearing fifty, and had aged beyond his years. The abscess on his leg was slowing him down, and there were days when he could hardly walk, let alone ride. Worse still, it oozed pus continually, and had to be dressed daily, not a pleasant task for the person assigned to do it as the wound stank dreadfully. As well as being afflicted with this, the King had become exceedingly fat: a new suit of armour, made for him at this time, measured 54 inches around the waist." Catherine was able to ignore these problems: "Catherine flattered Henry's vanity; she pretended not to notice his bad leg, and did not flinch from the smell it exuded. She was young, graceful and pretty, and Henry was entranced."

On 6th May, 1540, Henry VIII told Thomas Wriothesley the "King liketh not the Queen, nor ever has from the beginning." Henry asked Thomas Cromwell to find a way out of this problem because he had found a woman who he wanted to become his fifth wife. Cromwell suggested that he should arrange a divorce from Anne. The most obvious reason was the question of non-consummation, in itself this was the clearest cause of nullity by the rules of the church, but it was one that was difficult to establish.

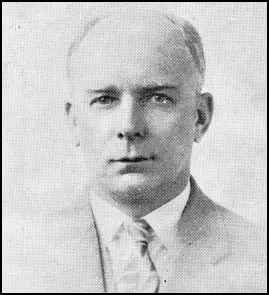

On this day in 1882 American radical Charles Ruthenberg, the son of a longshoreman, was born on 9th July, 1882, in Cleveland, Ohio. His father was very religious and he attended German- Lutheran elementary school. At the age of sixteen he found work sand-papering moldings in a picture-frame factory.

Ruthenberg later worked as a house-to-house salesman for a book publishing company. During this period he studied the Bible and theology and considered becoming a Church minister. According to Theodore Draper: "Instead, he became interested in evolution, then sociology, and finally socialism."

In 1909 Ruthenberg joined the Socialist Party of America. He made rapid progress and ran for mayor of Cleveland in 1911, for governor of Ohio in 1912 and for United States senator in 1914. He left his employment in the sales department of a roofing company in 1917 to become a full-time party organiser.

Ruthenberg was a strong opponent of the First World War and in July 1917 he was sentenced to one year in the workhouse for making anti-war and anti-conscription speeches. Ruthenberg was also a supporter of the Russian Revolution and joined the Communist Propaganda League.

In February 1919, Ruthenberg joined forces with Benjamin Gitlow, Bertram Wolfe and Jay Lovestone to create a left-wing faction that advocated the policies of the Bolsheviks in Russia. On 1st May 1919, Ruthenberg was attacked by the police during a political protest meeting.

On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported the pro-Bolshevik faction. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled. This group, including Ruthenberg, Earl Browder, Jay Lovestone, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Ella Reeve Bloor, Benjamin Gitlow, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. By the end of 1919 it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

Ruthenberg was appointed as National Secretary of the party. As the author of The Roots of American Communism (1957) pointed out: "Ruthenberg was the natural choice for National Secretary of the Communist party for two reasons - he was a native-born American, and he had demonstrated his ability to run an organization. Almost no one else qualified on both counts." Along with Louis Fraina, Jay Lovestone, Harry M. Wicks and Alexander Bittelman, Ruthenberg joined the Central Executive Committee of the party.

Initially, the American Communist Party was divided into two factions. One group led by Ruthenberg, that included Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe and Benjamin Gitlow, favoured a strategy of class warfare. Another group, led by William Z. Foster and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor.

Ruthenberg argued in an article published in Communist Labor: "The party must be ready to put into its program the definite statement that mass action culminates in open insurrection and armed conflict with the capitalist state. The party program and the party literature dealing with our program and policies should clearly express our position on this point. On this question there is no disagreement."

The growth of the American Communist Party worried Woodrow Wilson and his administration and America entered what became known as the Red Scare period. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the revolution, Alexander Mitchell Palmer, Wilson's attorney general, ordered the arrest of over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists. These people were charged with "advocating force, violence and unlawful means to overthrow the Government".

Ruthenberg was one of those arrested. In October 1920, Ruthenberg was tried for alleged violation of the state's Criminal Anarchism law, said to have been breached when he was involved in publishing the Left Wing Manifesto written by Louis Fraina the previous year. Ruthenberg was found guilty and sentenced to 5 years. He remained in Dannemora Prison until released on a $5,000 bond on 24th April, 1922.

On 14th July, 1923, Ruthenberg wrote in The Voice of Labour: "We know that it was our efforts, our work in the trade unions, our propagandizing, our leaflets, our newspapers, our speakers, our organizers, who to a large extent made possible this Convention. And because of that, we took the liberty of interposing with our organization of the militant self-sacrificing workers who are ready to give their strength and money to this cause, and who can be the motive force pushing it forward and spreading it out and making it a real mass movement. We know that - and we are not hiding it."

It was decided that because William Z. Foster had a strong following in the trade union movement that he should be the party candidate in the 1924 Presidential Election. Benjamin Gitlow, who represented the Ruthenberg group, was chosen as his running-mate. Foster did not do well and only won 38,669 votes (0.1 of the total vote). This compared badly with the other left-wing candidate, Robert La Follette, of the Progressive Party, who obtained 4,831,706 votes (16.6%).

The Comintern eventually accepted the leadership of Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone. As Theodore Draper pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "After the Comintern's verdict in favor of Ruthenberg as party leader, the factional storm gradually subsided. Membership meetings throughout the country 'unanimously endorsed' the new leadership and its policies. At the Seventh Plenum at the end of 1926, the Comintern, for the first time in five years, found it unnecessary to appoint an American Commission to deal with an American factional struggle... Ruthenberg's machine worked so smoothly and efficiently that it made those outside his inner circle increasingly restless. Beneath the surface of the factional lull, another rebellion smoldered, with the helpful encouragement of Cannon, who had touched off the anti-Ruthenberg rebellion three years earlier."

Charles Ruthenberg died suddenly in Chicago on 2nd March, 1927, three days after an emergency operation for appendicitis which had developed into peritonitis.

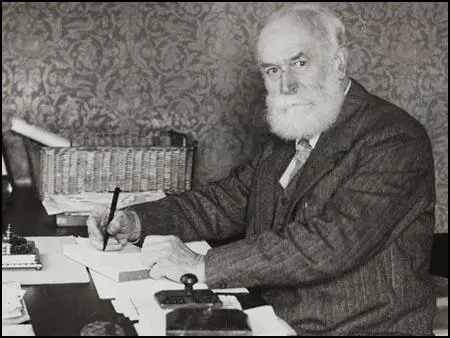

On this day in 1912 C. P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, criticises the tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. Although a long time supporter of women's suffrage, he only approved of the non-militant tactics of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. "We do not know whether the present House of Commons will be prepared to do justice to women. A few months ago there can be little doubt that it would, and nothing that has since happened supplies any adequate reason for a change of purpose. The follies and excesses of a small section of women, deeply resented and regretted by the vast majority of women, ought not to be allowed to weigh in the balance against a claim which has been admitted to be just."

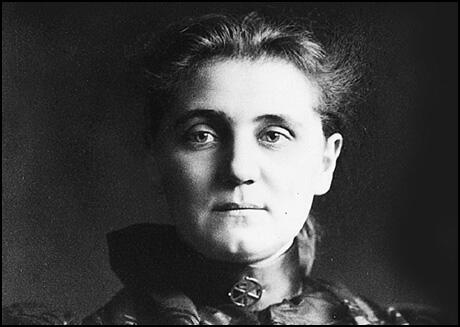

On this day in 1915 Jane Addams condemns the political leaders for the outbreak of the First World War.

The first thing which was striking is this, that the same causes and reasons for the war were heard everywhere. Each warring nation solemnly assured you it is fighting under the impulse of self-defense.

Another thing which we found very striking was that in practically all of the foreign offices the men said that a nation at war cannot make negotiations and that a nation at war cannot even express willingness to receive negotiations, for if it does either, the enemy will at once construe it as a symptom of weakness.

Generally speaking, we heard everywhere that this war was an old man's war; that the young men who were dying, the young men who were doing the fighting, were not the men who wanted the war, and were not the men who believed in the war; that someone in church and state, somewhere in the high places of society, the elderly people, the middle-aged people, had established themselves and had convinced themselves that this was a righteous war, that this war must be fought out, and the young men must do the fighting.

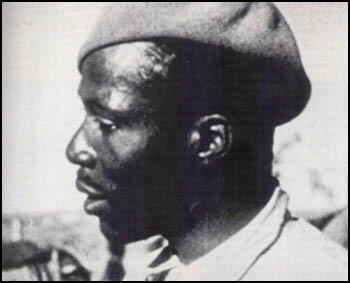

On this day in 1937 Oliver Law a black officer in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion is killed during the Spanish Civil War when he was leading his men in an attack against Mosquito Ridge.

Oliver Law was born in Texas in 1899. He served in the United States Army during the First World War. After six years in the forces he left to work in a cement factory. He later moved to Chicago where he drove a taxi, worked as a stevedore and ran a small restaurant.

During the Great Depression Law joined the American Communist Party and became active in the unemployment movement. This included the organization of the International Unemployment Day demonstration on 6th March 1930. During the demonstration Law, Joe Dallet, Steve Nelson and eleven other activists were arrested and badly beaten by the police. Two weeks after the beatings Law had recovered sufficiently to march with 75,000 demonstrators to demand unemployment insurance. Law also helped to organize mass protests against Benito Mussolini and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia.

In 1936 Oliver Law joined the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, a unit that volunteered to fight for the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. Law arrived in Spain in January 1937 and joined the other International Brigades at Albacete.

After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February, 1937.

General José Miaja sent three International Brigades to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. Law first saw action on 27th February. He performed so well in the battle he was promoted to commander of the machine-gun company. A few weeks later he became battalion commander. It was the first time in American history that an integrated military force was led by an African-American officer.

On 6th July 1937, the Popular Front government launched a major offensive in an attempt to relieve the threat to Madrid. General Vicente Rojo sent the Republican Army to Brunete, challenging Nationalist control of the western approaches to the capital. The 80,000 Republican soldiers made good early progress but they were brought to a halt when General Francisco Franco brought up his reserves.

After the war, an anti-Communist, William Herrick, claimed that Law had been murdered by his own men who objected to being led by a black man. This claim has been dismissed by Harry Fisher, the battalion runner, who took part in the offensive: "He was the first man over the top. He was in the furthest position when he was hit by a fascist bullet in the chest." David Smith, the medic who attempted to staunch the bleeding with a coagulant, also confirmed that he had been killed by the Nationalists.

Paul Robeson attempted to get a film made on the life of Law. Robeson later complained "the same money interests that block every effort to help Spain, control the Motion Picture industry, and so refuse to allow such a story."

On this day in 1943 the Whitehall Cinema in East Grinstead is bombed killing 108 (most of them children). On that day ten German aircraft crossed the Sussex coast at Hastings and headed for London. At 5.05 pm the air raid sirens sounded in East Grinstead. At the time 184 people were watching a film featuring Hopalong Cassidy in the Whitehall Cinema. A warning appeared on the screen that a German air raid was taking place but few of the audience, mostly children, took any notice of the message.

At 5.10 PM one pilot became separated from the other planes and decided that he would find another target before he returned home. A few minutes later he saw a train entering East Grinstead Station. He circled the town twice before dropping his bombs on the High Street.

One hit the Whitehall Cinema and others landed on several shops in the High Street and the London Road. As a result of the raid 108 people were killed and 235 were seriously injured. It was the largest loss of life in any air raid in Sussex.

On this day in 1953 Women Social & Political Union leader Annie Kenney, after a long, and steady decline, she died of diabetes at the Lister Hospital in Hitchen. Her husband, James Taylor, claimed that his wife never really recovered from her hunger strikes.

Annie Kenney, the daughter of Nelson Horatio Kenney and Anne Wood, was born at Springhead, a suburban area of Saddleworth, on 13th September 1879. Annie's mother had eleven children and worked with her husband in the Oldham textile industry. Annie was born prematurely and was not expected to survive. When Annie reached the age of ten she began work in a local cotton mill. Soon afterwards a whirling bobbin tore off one of her fingers.

At the age of thirteen Kenney became a full-time worker at the mill and had to get up at five in the morning to start at six, and finished work at 5.30 p.m. On arriving home she was expected to help with washing, cooking and scrubbing floors. If she had any free time she played with her dolls.

Annie later recalled that her "father never seemed to have any confidence in his children, he had very little in himself". Although Annie received very little education but her mother encouraged her to read and as a teenager she developed a strong interest in literature. She later recalled: "Mother allowed us great freedom of expression on all subjects.... I grew up with a smattering of knowledge on many questions." Annie was especially impressed by authors such as Tom Paine, Robert Blatchford,Edward Carpenter and Walt Whitman. After being inspired by an article she read in Robert Blatchford's radical journal, The Clarion, Annie joined the local branch of the Independent Labour Party.

At an Independent Labour Party meeting in 1905, Annie Kenney and her sister, Jessie Kenney, heard Christabel Pankhurst speak on the subject of women's rights. Annie was extremely impressed with the content of the speech and the two women soon became close friends. Annie decided to join the recently formed Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Emmeline Pankhurst commented: "There was something about Annie that touched my heart. She was very simple and seemed to have a whole-hearted faith in the goodness of everybody that she met." Christabel Pankhurst added: "She was eager and impulsive in manner, with a thin, haggard face, and restless knotted hands, from one of which a finger had been torn by the machinery it was her work to attend. Her abundant, loosely dressed golden hair was the most youthful looking thing about her... The wild, distraught expression, apt to occasion solicitude, was found on better acquaintance to be less common than a bubbling merriment, in which the crow's feet wrinkled quaintly about a pair of twinkling, bright blue eyes."

The WSPU was often accused of being an organisation that existed to serve the middle and upper classes. As Annie Kenney was one of the organizations few working class members, when the WSPU decided to open a branch in the East End, she was asked to leave the mill and become a full-time worker for the organisation. Annie joined Sylvia Pankhurst in London and they gradually began to persuade working-class women to join the WSPU.

Jessie Kenney also moved to the capital and become the private secretary to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "By the time she was 21 she was the Women's Social and Political Union's youngest organizer, working from Clement's Inn, arranging meetings, publicity stunts, interruptions of cabinet ministers' meetings and, as time passed, acts of militancy." She had different skills from her sister. Sylvia Pankhurst pointed out that Jessie was "eager in manner as her sister Annie, with more system and less pathos, and without any gift of platform speech."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Annie was a devoted follower of Christabel Pankhurst. "Annie's... devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience ... Just as no ordinary Christian can find that perfect freedom in complete surrender, so no ordinary individual could have given what Annie gave - the surrender of her whole personality to Christabel." Annie admitted that: "For the first few years the militant movement was more like a religious revival than a political movement. It stirred the emotions, it aroused passions, it awakened the human chord which responds to the battle-call of freedom ... the one thing demanded was loyalty to policy and unselfish devotion to the cause."

On 13th October 1905, Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting, the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle, a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she described what it was like to be in prison with Christabel: "Being my first visit to jail, the newness of the life numbed me. I do remember the plank bed, the skilly, the prison clothes. I also remember going to church and sitting next to Christabel, who looked very coy and pretty in her prison cap ... I scarcely ate anything all the time I was in prison, and Christabel told me later that she was glad when she saw the back of me, it worried her to see me looking pale and vacant.

On her release from prison Emmeline Pankhurst sent her to meet the journalist, William Stead. According to Fran Abrams: "Perhaps Emmeline knew of Stead's fondness for young girls, which Sylvia experienced too. On one occasion Annie had to appeal to Emmeline to ask him not to kiss her when she went to his office. But Annie liked Stead, and he quickly became a father figure. Before their first meeting was over she was sitting on the arm of his chair, telling him all about her life. He responded by telling her she must come to him if she was ever lonely or in trouble. Later he even let her use a room in his house in Smith Square to rest during Westminster lobbies and demonstrations, and he lent her £25 to help her organise her first big London meeting." Annie became very close to Stead and used to spend time with him at his house on Hayling Island in Hampshire. In one article Stead argued that Annie Kenney was the new Josephine Butler.

In May 1906 Annie, dressed as the sterotypical mill girl in clogs and shawl, she led a group of women to the home of Herbert Asquith, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. After ringing the bell incessantly, she was arrested and sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. On her release she went on holiday with Christabel Pankhurst and Mary Gawthorpe.

In 1907 Annie Kenney was appointed WSPU organiser at a salary of £2 a week, in the West of England. She was based in Bristol. It was not long before she recruited Victoria Lidiard, a photographer assistant, who became one of her assistants. The following year she met Mary Blathwayt at a WSPU meeting in Bath. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), claims that Blathwayt had fallen "under her spell and gave her a rose". Over the next few years she was to spend a lot of time at Blathwayt's home at Eagle House near Batheaston "where, for the first time, she began to learn French, to play tennis, to swim, to ride and to drive."

Kenney was to go to prison several times during the next six years. William Stead compared her to Joan of Arc, whereas Josephine Butler described her as: "A woman of refinement and of delicacy of manner and of speech. Her physique is slender, and she is intensively nervous and high strung. She vibrates like a harpstring to every story of oppression."

In March 1910, Annie and Christabel Pankhurst went on holiday together in Guernsey. A fellow member of the WSPU, Teresa Billington-Greig claimed that Annie was "emotionally possessed by Christabel". However, Mary Blathwayt, who spent a lot of time with Annie during this period argued that it was Annie who was the dominating personality as she had a "wonderful influence over people".

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that Annie Kenney had a series of romantic attachments with other suffragettes: "The relationship (with Christabel Pankhurst) would be mirrored, though never matched in its intensity, by a number of later relationships between Annie and other suffragettes. The extent of their physical nature has never been revealed, but it is certain that in some sense these were romantic attachments. One historian who argues that Annie must have had sexual feelings for other women adds that lesbianism was barely recognised at the time. Such relationships, even when they involved sharing beds, excited little comment. Already, Christabel had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia."

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account. The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else."

Teresa Billington-Greig has argued that Annie was also very close to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. "It is true that there was an immediate and strong emotional attraction between Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Annie Kenney... indeed so emotional and so openly paraded that it frightened me. I saw it as something unbalanced and primitive and possibly dangerous to the movement ... but the emotional obsession died out and the partnership... persisted for many years."

Annie admitted in her autobiography that suffragettes developed a different set of values to other women at the time: "The changed life into which most of us entered was a revolution in itself. No home life, no one to say what we should do or what we should not do, no family ties, we were free and alone in a great brilliant city, scores of young women scarcely out of their teens met together in a revolutionary movement, outlaws or breakers of laws, independent of everything and everybody, fearless and self-confident."

When Christabel Pankhurst fled to France to avoid arrest in 1912, Annie was put in charge of the WSPU in London. She appointed Rachel Barrett as her assistant. Every week Annie travelled to Paris to receive Christabel's latest orders. Fran Abrams has pointed out: "It was the start of a cloak-and-dagger existence that lasted for more than two years. Each Friday, heavily disguised, Annie would take the boat-train via La Havre. Sundays were devoted to work but on Saturdays the two would walk along the Seine or visit the Bois de Boulogne. Annie took instructions from Christabel on every little point - which organiser should be placed where, circular letters, fund-raising, lobbying MPs... During the week Annie worked all day at the union's Clement's Inn headquarters, then met militants at her flat at midnight to discuss illegal actions. Christabel had ordered an escalation of militancy, including the burning of empty houses, and it fell to Annie to organise these raids. She did not enjoy this work, nor did she agree with it. She did it because Christabel asked her to, she said later."

In 1912 the WSPU began a campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The WSPU also began a new arson campaign. Under the orders of Christabel Pankhurst, attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote.

The militant campaign was directed from Annie's flat that she shared with Jessie Kenney and another one of her lovers, Rachel Barrett. She asked Elizabeth Robins to witness a letter that Christabel Pankhurst sent her in which she gave her control of the WSPU in London.

Annie Kenny was charged with "incitement to riot" in April 1913. She was found guilty at the Old Bailey and was sentenced to eighteen months in Maidstone Prison. She decided that Grace Roe should now became head of operations in London. She immediately went on hunger strike and became the first suffragette to be released under the provisions of the Cat and Mouse Act. Kenney went into hiding until she was caught once again and returned to prison. That summer she escaped to France during a respite and went to live with Christabel Pankhurst in Deauville.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 ended the WSPU militant campaign for the vote. Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

Fran Abrams, the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued: "Annie, now becoming increasingly uncomfortable with Christabel's autocratic style, must have shown some hint of her true feelings because she was soon asked to leave the country. One of the leaders of the movement should be safe in case of invasion, Christabel said."

Annie Kenney was sent to the United States. She did not enjoy the experience and when Christabel Pankhurst arrived in the country to make a speech at Carnegie Hall urging Americans to enter the war on the side of the Allies, Kenney managed to persuade Christabel to allow her to come home.

In 1915 the WSPU sent Annie Kenney to Australia to help the prime minister, William Hughes, in a referendum campaign on conscription. On her return she worked with David Lloyd George to help find female recruits for the munition factories. She was also involved in organizing an Anti-Bolshevist campaign against strikes.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918, Kenney helped Christabel Pankhurst in her election campaign in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, Christabel lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party.

In 1918 Annie Kenney went to live with Grace Roe in St Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex. The two women became followers of Annie Besant, who was the leader of the Theosophy movement in Britain. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), Grace Roe later "remarked on the part played by theosophists behind the scenes of the militant suffrage movement. She made the point that theosophy not only gave a spiritual dimension to their lives but, cutting across class, put people in touch with each other who would have been unlikely otherwise to meet."

While staying with her sister on the Isle of Arran, she met James Taylor (1893-1977). Mary Blathwayt claims in her diary that Taylor "is quite simple like Annie and has a divine singing voice." The couple were married in April 1920 at St Cuthbert's Church. They moved to Letchworth, where Taylor was appointed maintenance engineer at St Christopher's School. A son, Warwick Kenney Taylor, was born in February, 1921. Her sister, Jessie Kenney, worked as a steward on a cruise liner but used Annie's home as a base.

Annie Kenney lost interest in politics but she continued to keep in contact with Christabel Pankhurst. In her autobiography, Memories of a Militant (1924) she wrote: "There is a cord between Christabel and me that nothing can break - the cord of love... We started militancy side by side and we stood together until victory was won."