On this day on 1st September

On this day in 1876 Harriet Shaw Weaver, the sixth of eight children of Frederic Poynton Weaver, a doctor, and his wife, Mary Wright, was born in Frodsham, Cheshire, on 1st September 1876. The family was extremely wealthy as her mother having inherited a fortune from her father, made in the cotton industry.

Harriet was educated at home by a governess, Marion Spooner. According to the authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970): "Her education owed much also to the governess who came when she was ten and remained until she was eighteen and her formal schooling was brought to an end. Miss Marion Spooner was a young gentlewoman of decided powers. She was a good linguist and very musical, though these were qualities to which Harriet and the others, who all had no ear, could not respond. She had a vivid interest in history and in current affairs and pronounced Liberal views. To these Harriet warmed. Under Miss Spooner's tutelage she probably received as broad an education as any single-handed teacher could have given her." Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) added: "Her early influences came from her liberal governess, Marion Spooner, and her own, often secretive, reading." This included The Subjection of Women, a book written by John Stuart Mill and Helen Taylor.

In 1891 the family moved to Hampstead. Three years later, Marion Spooner left, though she was to remain a lifelong friend. Harriet wanted to go to university but her father rejected the idea. "What would be the use of such a course?" He pointed out that she would never need to earn a living and that he was unhappy with the pursuit of a profession for its own sake. Harriet continued to read left-wing books and she became a socialist and a supporter of women's suffrage.

Harriet Shaw Weaver also did charity work in Bermondsey. In 1902 she became honorary secretary of the East End branch of the Children's Country Holiday Fund. A fellow committee member was Robert Ensor, the author of Modern Socialism (1904) and E. J. Urwick, an economist and political philosopher.

In 1905 Harriet Shaw Weaver began attending lectures at the London School of Sociology and Social Economics that had been founded two years previously by the Charity Organization Society. She also attended a course of lectures on "The Economic Basis of Social Relations" at the London School of Economics. Harriet Weaver also worked with William Beveridge at Toynbee Hall when she was running the East End Branch of the Invalid Children's Aid Association.

Harriet was described during this period by the authors of Dear Miss Weaver: "She was a little above middle height, slim and straight. Her eyes were small, round and a clear blue. Her brown hair, taken back into a bun." One of her contemporaries described her as being "very neat, very austere, like a beautiful nun". Another friend said she was "more reserved than shy" whereas another pointed out that Harriet rarely spoke as she her "urge was to listen". Her sister, Maude Weaver claimed that she had no interest in the other sex, except as human beings, "there was never a flicker of a flirtation with anyone."

Harriet's brother, Harold, died in 1909 after accidentally taking an overdose of sleeping tablets. She later wrote: "What comforted me most when he died... was the thought that it was better to have had him as a dear brother for his short life than not to have had him." Her biographer has pointed out that she "felt his loss acutely" and was "exhausted and unwell for long afterwards". A friend, Edith Munro, wrote to her suggesting that they spend time together: "I know that the light seems to have gone out of your life and nothing seems worth doing or thinking of any more.... Couldn't we go out for a long long walk. I needn't speak at all if you would rather not. If you knew how I longed to be with you. I have loved you so much for so many years and now that you are in trouble I seem quite useless."

Harriet Shaw Weaver became interested in the subject of women's suffrage and joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). She sold Votes for Women and distributed pamphlets but never took part in any demonstrations and resigned after the start of the arson campaign. She continued to be interested in the struggle for the vote and she began subscribing to The Freewoman. The most controversial aspect of the journal was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden, the editor, began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Edmund Haynes, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Rebecca West, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Harriet Shaw Weaver was one of those who joined the Freewoman Discussion Circle in London. The authors of Dear Miss Weaver (1970) pointed out: "It was a successful group, inaugurated at a meeting of more than eighty people. The numbers increased so fast that at its first meeting-room, at the Suffragette shop, was too small. So was its second, at the Eustace Miles vegetarian restaurant; and its final home was at the Chandos Hall. The programme for the session July to October 1912 included talks on Eugenics by Mrs Havelock Ellis and on Divorce Reform by E.S.P. Haynes. Other subjects were Sex Oppression and the Way Out, Celibacy, Prostitution, and the Abolition of Domestic Drudgery." Rebecca West recalled that at the meetings: "Everyone behaved beautifully - it's like being in Church, except Rona Robinson and myself. Barbara Low has spoken very seriously to me about it."

In September 1912, The Freewoman was banned by W. H. Smith because "the nature of certain articles which have been appearing lately are such as to render the paper unsuitable to be exposed on the bookstalls for general sale." Dora Marsden argued that this was not the only reason the journal was banned: "The animosity we rouse is not roused on the subject of sex discussion. It is aroused on the question of capitalism. The opposition in the capitalist press only broke out when we began to make it clear that the way out of the sex problem was through the door of the economic problem."

Charles Grenville wrote to Dora Marsden complaining that the journal was losing about £20 a week and told her he was thinking of withdrawing as the publisher of the magazine. Marsden replied: "You have put money into the paper. I have put in the whole of my brain, power and personality. Without your money I would not have started, without my brain the paper could not have lived and shown the signs of flourishing which it undoubtedly has."

The last edition of The Freewoman appeared on 10th October 1912. Dora Marsden told her readers: "The editorial work has not been easy. We have been hemmed in on every side by lack of funds. We have, moreover, been promoting a constructive creed, which had not only to be erected as we went along, we had also to deal with the controversy which this constructive creed left in its wake.... The entire campaign has been carried on indeed only at the cost of a total expenditure of energy, and we, therefore, do not hold it possible to continue the same amount of work, with diminished resources, if in addition, we have to bear the entire anxiety of securing such resources as are to be at our disposal."

Dora appealed to readers to help fund a new magazine. Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw both sent money. Lilian McErie also contributed: "No paper has given me keener pleasure than yours. Its fearlessness and fairness made all lovers and seekers after truth respect it and love it even while differing from many of the opinions expressed therein."

In February 1913 Harriet Shaw Weaver met Dora Marsden, who had just inherited a large sum of money from her father. As Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit, pointed out: "They were in many ways totally unsuited - on the one hand, the rebellious, radical intellectual and on the other, the quiet, modest, unassuming and orderly Weaver. Yet they took an immediate liking towards each other - Weaver impressed by Dora's intelligence and indeed, her beauty, and Dora by Harriet's keen but systematic approach to the re-launch of the paper. Dora had originally just wanted a chat but they ended up in effect having a business meeting while all the time establishing their mutual respect and admiration".

The New Freewoman was launched in June 1913. The journal, published fortnightly, was priced at 6d but readers were asked to pay £1 in advance for 18 months' copies. Dora Marsden wrote in the first edition: "The New Freewoman is not for the advancement of Women, but for the empowering of individuals - men and women.... Editorially, it will endeavour to lay bare the individual basis of all that is most significant in modern movements including feminism. It will continue The Freewoman's policy of ignoring in its discussion all existing taboos in the realms of morality and religion."

Harriet Shaw Weaver put up £200 to fund the magazine and this gave her a controlling interest in the venture. Dora Marsden was editor, Rebecca West assistant editor and Grace Jardine (sub-editor and editorial secretary). The women were all employed on a salary of £1 a week. Later, Ezra Pound, became the journal's literary editor. Weaver's biographer, Rachel Cottam, has argued: "Over the following years she gave regular donations of money, usually anonymously, and became involved in all the details of its organization and finance, finally taking on the role of editor. Though lacking confidence in her own writing, she contributed a number of reviews (signing herself Josephine Wright) and, as editor, wrote the occasional leader article."

Harriet and Dora Marsden became very close. Dora wrote to Harriet claiming that "you have been a perfect treasure to me and the paper". Harriet wrote back expressing her love for Dora. Rebecca West also enjoyed working under Dora, telling her that she was a "wonderful person, you not only write these wonderful first pagers but you inspire other people to write wonderfully."

The New Freewoman gradually moved away from its feminist origins. George Lansbury complained about Marsden's abandonment of socialism and others disliked the emphasis she placed on individualism. Her critics included Rebecca West who resigned her post in October 1913 having become disillusioned with the direction the journal was taking. Later she admitted she strongly disapproved of Dora's "aggressive individualism" and her "egotistic philosophy". Dora replaced Rebecca with the young poet, Richard Aldington.

At a director's meeting on 25th November 1913, it was decided to change the name of the The New Freewoman to The Egoist: An Individualist Review. Bessie Heyes complained to Harriet Shaw Weaver about the change of name. "Don't you yourself think that the paper is not accomplishing what we intend to do? I had such hopes of The New Freewoman and it seems utterly changed." The journal lasted for only seven months and thirteen issues. During this time it only obtained 400 or so regular readers. Ezra Pound wanted the The Egoist to become more of a literary journal. In early 1914 he persuaded Dora Marsden to serialize A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, an experimental novel written by James Joyce.

In the summer of 1914 Dora Marsden handed over the editorship of the journal to Harriet Shaw Weaver. Marsden now assumed the role of contributing editor. This allowed her to concentrate on her philosophical research and writings. However, both women were concerned by the poor sales figures of the journal. After briefly reaching 1,000 copies it had now fallen to a circulation figure of 750.

In January 1916, Harriet Shaw Weaver argued that despite poor sales she was determined to continue supporting the The Egoist. "It has skirted all movements and caught on to none.... The Egoist is wedded to no belief from which it is willing to be divorced. To probe to the depths of human nature, to keep its curiosity in it fresh and alert, to regard nothing in human nature as foreign to it, but to hold itself ready to bring to the surface what may be found, without any pre-determination to fling back all but unwelcome facts - such are the high and uncommon pretensions upon which it bases its claims to provenance."

James Joyce failed to find a publisher for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Harriet Shaw Weaver agreed to establish the Egotist Press and the book was published in February 1917. The book was praised by critics such as H. G. Wells but was attacked by the mainstream press. The editor of The Sunday Express described it as "the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature."

According to Rachel Cottam: "From 1916 Joyce and Weaver corresponded almost daily: she commented on his manuscripts, corrected his proofs, discussed his frustrations and aspirations, and gradually became involved in every aspect of his own and his family's well-being. Though she was aware that he spent money recklessly and sometimes drank to excess, she endeavoured to provide him with an assured family income by transferring him substantial sums of her capital." Rebecca West argued that without Weaver's dedication, it is "doubtful whether Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom would have found their way into the world's mind".

In January 1919 The Egoist: An Individualist Review began the serialization of Joyce's Ulysses. However, sales of the journal had fallen from 1,000 in May 1915 to 400 and Harriet Shaw Weaver, decided to bring the journal to an end.

In 1931, Weaver joined the Labour Party. However, she became a fierce critic of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government. In 1938 she switched her alliance to the Communist Party of Great Britain. She became a committed member and sold copies of The Daily Worker in the street.

Harriet Shaw Weaver, who never married, died at Castle End, near Saffron Walden, Essex, on 14th October 1961. and was cremated at Oxford.

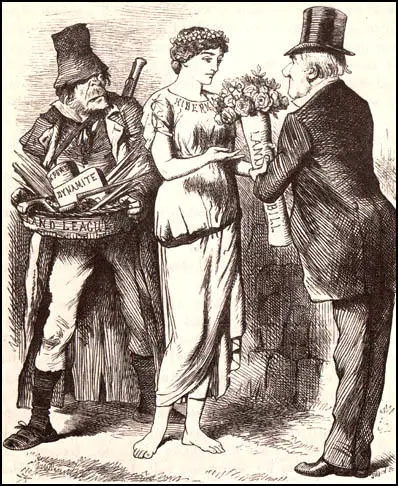

On this day in 1893 the Second Home Rule Bill was passed in the House of Commons. In the 1892 General Election held in July, Gladstone's Liberal Party won the most seats (272) but he did not have an overall majority and the opposition was divided into three groups: Conservatives (268), Irish Nationalists (85) and Liberal Unionists. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, refused to resign on hearing the election results and waited to be defeated in a vote of no confidence on 11th August. Gladstone, now 84 years old, formed a minority government dependent on Irish Nationalist support.

A Second Home Rule Bill was introduced on 13th February 1893. Gladstone personally took the bill through the "committee stage in a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance". After eighty-two days of debate it was passed in the House of Commons on 1st September by 43 votes (347 to 304). Gladstone wrote in his diary, "This is a great step. Thanks be to God."

On 8th September, 1893, after four short days of debate, the House of Lords rejected the bill, by a vote of 419 to 41. "It was a division without precedent, both for the size of the majority and the strength of the vote. There were only 560 entitled to vote, and 82 per cent of them did did so, even though there was no incentive of uncertainty to bring remote peers to London."

On this day in 1907 union leader Walter Reuther, the son of a trade union and socialist activist, was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. At sixteen he became an apprentice tool and die maker and three years later moved to Detroit.

In 1929 Reuther enrolled at Detroit City College to study law. He became president of the Social Service Club (the campus arm of the Socialist Party). While at college Reuther arranged for leading socialists such as Norman Thomas and Scott Nearing to speak at meetings.

Reuther joined the Ford Motor Company but his union activities resulted in him losing his job in 1933. Unable to find work during the Great Depression, Reuther left the United States and eventually found employment in an automobile factory in the Soviet Union. Unhappy with the lack of political freedom in the country, Reuther returned to the United States where he found employment at General Motors and became an active member of the United Automobile Workers (UAW).

Reuther remained active in the Socialist Party and in 1937 failed in his attempt to be elected to the Detroit City Council. However, impressed by the efforts by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to tackle inequality, he eventually joined the Democratic Party.

Reuther led several strikes and in 1937 and 1940 was hospitalized after being badly beaten by strike-breakers. He also survived two assassination attempts during this period although one attack left his right hand permanently crippled.

Reuther gradually became a leading figure in the United Automobile Workers (UAW) and in 1946 was elected president after a bitter struggle with supporters of the American Communist Party. Six years later Reuther succeeded Philip Murray as president of the Congress for Industrial Organisation(CIO).

After the Second World War Reuther emerged as one of trade union's leading progressive figures. His support for civil rights and social welfare legislation made him unpopular with conservatives. In the early 1950s the Senate Select Committee on Labor began investigating the trade union movement. Robert Kennedy, chief counsel of the committee, began investigating James Hoffa and the Teamsters Union. Hoffa was a well-known supporter of the Republican Party, and party members on the committee, including Joe McCarthy, Barry Goldwater and Karl Mundt, insisted that trade union leaders associated with the Democratic Party should also be investigated. Reuther was charged but Robert Kennedy discovered no evidence of corruption.

Under Reuther's leadership the UAW grew to 1.5 million members. A successful negotiator, in 1955 he managed to obtain an agreement that gave auto workers almost as much take-home pay when laid off as when at work.

In 1955 the CIO merged with the American Federation of Labour (AFL). George Meany became president of the AFL-CIO and Reuther was appointed vice-president.

Reuther was an active supporter of African American civil rights and participated in both the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs (August, 1963) and the Selma to Montgomery March (March, 1965).

Reuther found George Meany conservative and dictatorial and in 1968 led the out of the AFL-CIO federation. The following year he joined with the Teamsters Union to form Alliance for Labor Action. Walter Reuther, who was active in the campaign against the Vietnam War, was killed in a plane crash in Pellston, Michigan, on 9th May, 1970.

On this day in 1908 social activist Lou Kenton, the first of nine children, was born in Stepney. His Jewish parents had fled from the Ukraine during the pogroms. Lou was one of nine children living in a three-roomed flat. His father, a tailor, died of tuberculosis when he was a child.

After leaving school at fourteen Kenton got a job in a paper factory in London. He later recalled: "On my first day at the factory, I was involved in seven fights. I reacted very badly to being called a Jew bastard."

Kenton joined the Communist Party in 1929 and was involved in the campaign against Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists in the East End of London. This included heckling at the famous BUF meeting in Olympia meeting in 1934. Kenton also took part in the battle of Cable Street in November, 1936. He later recalled: "I had a motorbike at the time and was able to whizz around the periphery of the crowd, going from section to section to warn them what was going on. We had a number of people watching the Fascists and quickly telling the crowd what was happening. We were able to get word to the majority of the crowd in Commercial Road, which was some way from Cable Street, of what was happening. The dockers themselves were manning Cable Street and had thrown up barricades. As soon as the word got around that Mosley was on the way towards Cable Street, within minutes thousands of people were there. Although hundreds of police and the Mosley crowd tried to break through, they were stopped."

Kenton married Lillian, an Austrian nurse who had fled Nazi Germany. Soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Kenton and his wife attended an anti-fascist meeting with Ben Glazer. "One evening myself and Lillian and my dear friend Ben Glazer walked along the Embankment. We walked - stopped at many coffee stalls - talking, wondering what it would be like in Spain. We didn't finally decide until we reached a coffee stall at Westminster Bridge, opposite the House of Commons. I think we had already decided to go, but didn't say so in as many words. I think we were deeply fearful in our hearts, hut none of us wanted to show our fears. What would it be like? Would we ever come back? What if we were captured? And when we decided - how we embraced! Lillian kissed us both. We linked arms and walked almost cheerfully down Whitehall to the all-night Lyons Corner House just off Trafalgar Square for more coffee and eggs and bacon. From there we decided that tomorrow morning we would go and volunteer."

Lillian Kenton joined the nursing staff set up by the British Medical Aid Committee. Lou wanted to join the International Brigades in the front-line but the Communist Party arranged for him to work with the medical teams that had been sent to Spain. He arrived in Valdeganga soon after the Battle of Jarma. "Every day I was either on my motorcycle or driving an ambulance, picking up wounded from the base camps. Often I would go to different units of the battalion scattered around Spain with messages or parcels of medical equipment, where they were in short supply.... I lived on grapes growing by the roadside, for days on end." Kenton returned to England in 1938 to raise money for the Republican Army.

During the Second World War he was badly injured in a bombing raid and was hospitalised for two years. According to his friend, Steve Donnelly: "After the war he worked as an organiser for the Communist party in London, and helped run the ex-servicemen's squatting movement. He incentivised recruitment by offering a trip to Paris for Bastille Day as a prize. The trip soon became an event in its own right and in 1947 it attracted 1,000 people who paid their own way."

Kenton continued to work in the print industry. He was also played an active role in Progressive Tours, the travel company that organised trips to communist countries in Eastern Europe. In 1955 he organised a trip to the village of Lidice, the scene of one of the worst German atrocities of the war, after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942. The village was razed to the ground and its 173 male inhabitants were murdered. The 198 women were sent to a Concentration Camp in Ravensbueck.

Kenton remained in the Communist Party until the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968. He then became active in the Labour Party. According to Steve Donnelly: "In retirement he found a new career, as a prolific maker of commemorative pottery for unions and other organisations. In 2009, he was one of the IB veterans awarded Spanish citizenship."

Lou Kenton, died aged 104, in September, 2012.

On this day in 1914 International Manifesto of Women is published. "We, the women of the world, view with apprehension and dismay the present situation in Europe, which threatens to involve one continent, if not the whole world, in the disasters and horrors of war ... Powerless though we are politically, we call upon the governments and powers of our several countries to avert the threatened unparalleled disaster ... Whatever its result the conflict will leave mankind the poorer, will set back civilization, and will be a powerful check to the gradual amelioration in the condition of the masses of the people, on which so much of the real welfare of nations depends. We women of twenty-six countries ... appeal to you to leave untried no method of conciliation or arbitration for arranging international differences which may help to avert deluging half the civilized world in blood."

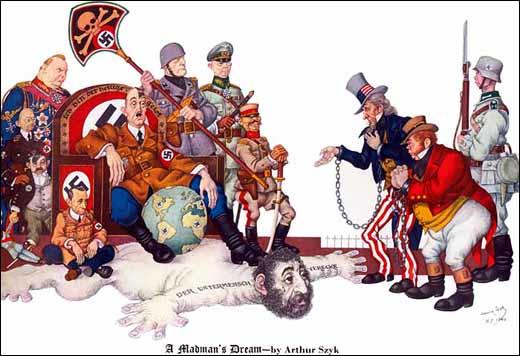

On this day in 1939 the German Army invades Poland. Fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility".

At a meeting of the Cabinet on 2nd September, the Cabinet wanted the prime minister to declare war on Germany. Chamberlain refused and argued it was still possible to avoid conflict. That night he announced in the House of Commons that he was offering Hitler a conference to discuss the subject of Poland if the "Germans agreed to withdraw their forces (which was not the same as actually withdrawing them), the British government would forget everything that had happened, and diplomacy could start again."

Clement Attlee was not in the House of Commons as he was recovering from a serious operation. It was acting leader, Arthur Greenwood, who replied to Chamberlain's statement. As he stood up, Leo Amery shouted "Speak for England, Arthur!". Greenwood said: "I am gravely disturbed. An act of aggression took place 38 hours ago. The moment that act of aggression took place one of the most important treaties of modern times automatically came into operation. There may be reasons why instant action was not taken. I am not prepared to say - and I have tried to play a straight game - I am not prepared to say what I would have done had I been one of those sitting on those Benches. That delay might have been justifiable, but there are many of us on all sides of this House who view with the gravest concern the fact that hours went by and news came in of bombing operations, and news today of an intensification of it, and I wonder how long we are prepared to vacillate at a time when Britain and all that Britain stands for, and human civilisation, are in peril. We must march with the French."

Chamberlain had lost the support of his own MPs. He was shocked by this reaction and Lord Halifax commented that he had "never seen the Prime Minister so disturbed". Members of the Cabinet were also angry with Chamberlain's performance in the House of Commons. Several members of the Cabinet assembled in the office of John Simon. He later recalled: "The language and feelings of some of my colleagues were so strong and deep that I thought it right at once to inform the Prime Minister." The men drafted a letter that said "that our view was that in no circumstances should the expiry of the ultimatum go beyond 12 noon tomorrow, and even this extension of twelve hours beyond the Cabinet's earlier decision would only be acceptable if it was the necessary price of French co-operation".

Shortly before midnight, on 2nd September, 1939, the Cabinet met for a second time. Members, led by Leslie Hore-Belisha, argued that the government must stop procrastinating and declare war or else he would be defeated in the House of Commons. It was agreed to issue an ultimatum which would be delivered by Nevile Henderson to the German government in Berlin at 9.00 a.m. on 3rd September 1939. It stated that unless Hitler made a firm promise to withdraw his troops from Poland by 11.00 a.m. then Britain would declare war.

The following day Neville Chamberlain went on radio to announce: "Britain is at war with Germany" and went on to say: "This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established."

Richard Lamb, the author of The Ghosts of Peace (1987) described it as a "pathetic broadcast" and "instead of promising speedy help to the ally on whose behalf Britain was going to war, he spoke of his personal grief." Although the people of Poland "expected immediate help, Britain had no intention of coming to Poland's aid." On 9th September, 1939, a Polish military mission led by General Norwid Neugebauer, arrived in London to have talks with William Ironside the Chief of the General Staff. However, all Ironside could offer was a few thousand old rifles and a few million rounds of ammunition, and he advised them to buy arms from neutral countries such as Spain and Belgium.

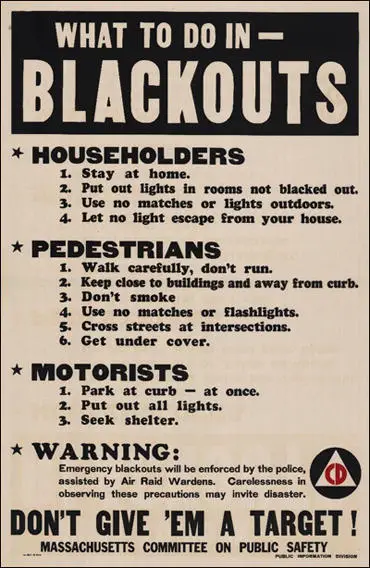

On this day in 1939 Harold Nicolson writes in a diary about the blackout.

Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet.