On this day on 1st October

On this day in 1569 Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, was arrested by Queen Elizabeth for conspiring to marry Mary Queen of Scots. Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) has explained why Mary was interested in marrying Norfolk. "He had been discerned by Mary to be favourable to her cause. Though nominally a Protestant his connections were those of the ancient Catholic nobility; he had been married three times and at thirty-two was once again a widower. The urgent need to settle the succession, and Elizabeth's steady refusal to make an immediate marriage, were leading some people to say that whatever the rights or wrongs of the Scots, the English would be best served by recognizing, under suitable safeguards to the Protestant religion, Mary's claim as heiress presumptive, and marrying her to a distinguished Englishman. Norfolk, the premier Duke of England and head of the great family of Howard, who called himself a Protestant and at the same time was acceptable to the Catholics, might answer the wishes of a very numerous party, to whom the idea of such a marriage and of Mary's recognition seemed the likeliest way of laying the spectre of civil war. Norfolk himself was strongly drawn to the scheme, which gave a romantic and splendid turn to his own fortunes and had the exalted character of a high enterprise undertaken for the public good. He sounded Sussex, who did not altogether reject the plan but made it clear that if he were to have anything to do with it, it must be laid before the Queen, and no steps in the matter must be taken without her knowledge and concurrence. Other peers gave him a more discreet encouragement, among whom was Leicester."

On this day in 1688 Prince William III of Orange accepts invitation of take up the British crown. Some members of the House of Commons sent messages to Holland inviting James's daughter, Mary Henrietta Stuart and her husband, William to come to England. Mary and William were told that, as they were Protestants, they would have the support of Parliament if they attempted to overthrow James. In November 1688, William, Prince of Orange and his Dutch army arrived in England. When the English army refused to accept the orders of their Catholic officers, James fled to France. As the overthrow of James had taken place without a violent Civil War, this event became known as the Glorious Revolution. William and Mary were now appointed by Parliament as joint sovereigns. However, Parliament was determined that it would not have another monarch that ruled without its consent. The king and queen had to promise they would always obey laws made by Parliament. They also agreed that they would never raise money without Parliament's permission. So that they could not get their own way by the use of force, William and Mary were not allowed to keep control of their own army. In 1689 this agreement was confirmed by the passing of the Bill of Rights.

On this day in 1746 Bonnie Prince Charlie flees to France. Later, as a result of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, it was agreed that Charles Stuart should live in Avignon. When James Stuart died in 1766, Pope Clement XIII, keen to improve relations with Britain, refused to accept Charles Stuart as king. Charles Stuart married Princess Louise of Stolberg in 1772 but produced no heirs and when he died in 1788 the Stuart claim to the throne came to an end.

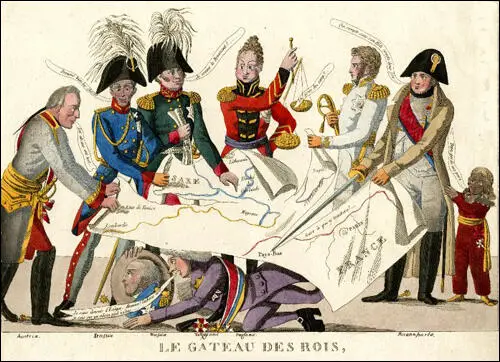

On this day in 1814 Lord Castlereagh attended the opening of the Congress of Vienna, which redrew Europe's political map after the defeat of Napoléon Bonaparte.

On this day in 1847 Annie Wood, the daughter of William Wood and Emily Morris Wood, was born at 2 Fish Street, London. Annie's father, an underwriter, died when she was only five years old. Without any savings, Annie's mother found work looking after boarders at Harrow School.

Mrs. Wood was unable to care for Annie and she persuaded a friend, Ellen Marryat, who lived in Charmouth in Dorset, to take responsibility for her education. Annie later recalled: "Miss Marryat had a perfect genius for teaching, and took in it the greatest delight... She taught us everything herself except music, and for this she had a master, practising us in composition, in recitation, in reading aloud English and French, and later, German, devoting herself to training us in the soundest, most thorough fashion. No words of mine can tell how much I owe her, not only of knowledge, but of that love of knowledge which has remained with me ever since as a constant spur to study."

Marryat disagreed strongly with the idea of rote-learning. The children wrote about what interested them. They were also taught to think clearly. However, Marryat was "an extreme evangelical evangelical; sin, damnation, conversion, and permanent recourse to the Scriptures formed the regime". The children were forced to read both the Bible and the Fox Book of Martyrs and therefore "encouraging more daydreams of facing the stake or the rack."

At the age of sixteen, Annie left the care of Miss Marryat. She was intensely devout and in her own words, "the very stuff of which fanatics were made". Annie was an attractive young woman and her "dark curls and a trim, tiny figure appeared at the Harrow balls and inspired several proposals of marriage."

In April 1866 Annie met "the Rev. Frank Besant, a young Cambridge man, who had just taken orders, and was serving the little mission church as deacon" in Clapham. (5) A former schoolteacher, he was seven years older than Annie and according to one of her biographers, Anne Taylor, he was "an impecunious, parsimonious, stiff-necked young man from Portsea, whose evangelicalism was approvingly described as serious".

A few months later he suddenly asked her to be his wife when he was on the point of getting on to a train: "Out of sheer weakness and fear of inflicting pain I drifted into an engagement with a man I did not pretend to love." The following year she met William Prowting Roberts, the 61-year-old, radical lawyer, who was a close friend of Ernest Jones, a Chartist and a follower of Karl Marx. Roberts, was a lawyer who had fought to improve the conditions of women and children working in the coal mines.

"He (William Prowting Roberts) worked hard in the agitation which saved women from working in the mines, and I have heard him tell how he had seen them toiling, naked to the waist, with short petticoats barely reaching to their knees, rough, foul-tongued, brutalised out of all womanly decency and grace; and how he had seen little children working there too, babies of three and four set to watch a door, and falling asleep at their work to be roused by curse and kick to the unfair toil. The old man's eye would begin to flash and his voice to rise as he told of these horrors, and then his face would soften as he added that, after it was all over and the slavery was put an end to, as he went through a coal district the women standing at their doors would lift up their children to see 'Lawyer Roberts' go by, and would bid 'God bless him' for what he had done."

Roberts had a major impact on Annie's political views. "This dear old man was my first tutor in Radicalism, and I was an apt pupil. I had taken no interest in politics, but had unconsciously reflected more or less the decorous Whiggism which had always surrounded me. I regarded the poor as folk to be educated, looked after, charitably dealt with, and always treated with most perfect courtesy, the courtesy being due from me, as a lady, to all equally, whether they were rich or poor. But to Mr. Roberts the poor were the working-bees, the wealth producers, with a right to self-rule not to looking after, with a right to justice, not to charity, and he preached his doctrines to me in season and out of season."

Annie Wood married Frank Besant in Hastings on 21st December, 1867. It was a very unhappy marriage: "Frank Besant seems to have been rigid, charmless and entirely set in his belief that a husband's word is law within his household; Annie was delicate and intellectual and cosseted... It is curious that, believing marriage to be the one and only destiny of women. Victorian families so often sent their daughters into it not only sexually ignorant but ignorant of housekeeping and money management."

Annie Besant admitted many years later that she had made a terrible mistake marrying Frank Besant. "In truth, I ought never to have married, for under the soft, loving, pliable girl there lay hidden, as much unknown to herself as to her surroundings, a woman of strong dominant will, strength that panted for expression and rebelled against restraint, fiery and passionate emotions that were seething under compression - a most undesirable partner to sit in the lady's armchair on the domestic rug before the fire".

By the time she was twenty-three Annie Besant had two children, Digby (16th January 1869) and Mabel (28th August 1870). Annie had difficult births and when she suggested to her husband that they should try "family limitation" he gave her a beating. "On various occasions he threw her over a stile, kneed her and pushed her out of bed so that she crashed on the floor and was badly bruised."

However, Annie was deeply unhappy because her independent sprit clashed with the traditional views of her husband. Annie also began to question her religious beliefs. In 1872 she heard the eloquent sermons of Charles Voysey, who was a leading Dissenter preacher. Voysey, who was considered to be a theist, denied the perfection of Jesus and the authority of the Bible. Annie sought Voysey's advice on religious matters and "struck by the unusual appearance and earnestness of this beautiful woman of twenty-five", he invited her to his home in Dulwich.

Voysey introduced Annie to Thomas Scott, a sixty-four year-old freethinker. "At that time Thomas Scott was an old man, with beautiful white hair, and eyes like those of a hawk gleaming from under shaggy eyebrows. He had been a man of magnificent physique, and, though his frame was then enfeebled, the splendid lion-like head kept its impressive strength and beauty, and told of a unique personality. Well born and wealthy, he had spent his earlier life in adventure in all parts of the world, and after his marriage he had settled down at Ramsgate, and had made his home a centre of heretical thought."

Scott was impressed with Annie Besant and invited her to write a pamphlet on her religious views. She agreed to his request and Scott published, On the Deity of Jesus of Nazareth: An Inquiry into the Nature of Jesus, in March 1873. Frank Besant became aware of this pamphlet and issued an ultimatum: Annie was to be seen to take holy communion regularly at his church or she was to leave the family home. Annie later recalled that she chose "expulsion" over "hypocrisy". In October, 1873, she signed a deed of separation that allowed her to keep Mabel with her, but had to leave Digby, aged four, with his father.

Annie Besant found temporary work as a governess in Folkstone. However, in 1874 her mother became ill and so she rented a house in Upper Norwood so she could look after her. Emily Wood died on 10th May. During this period she produced pamphlets for Thomas Scott. In addition to the payment she received for this work, she was also welcome to take meals at Scott's house. She later recalled that he was the first man outside her family whom she could truthfully say she loved."

In July 1874, Annie purchased a copy of the The National Reformer. The newspaper had been established by Charles Bradlaugh and Joseph Barker. They believed that religion was blocking progress and advocated what they called an atheistic Secularism. The newspaper advocated a whole range of reforms including universal suffrage and republicanism. Bradlaugh had also helped establish the National Secular Society.

Annie Besant later pointed out: "Attracted by the title, I bought it. I read it placidly in the omnibus on my way to Victoria Station, and found it excellent, and was sent into convulsions of inward merriment when, glancing up, I saw an old gentleman gazing at me, with horror speaking from every line of his countenance. To see a young woman, respectably dressed in crape, reading an Atheistic journal, had evidently upset his peace of mind, and he looked so hard at the paper that I was tempted to offer it to him, but repressed the mischievous inclination".

Annie decided to write to the newspaper and asked if "it was necessary for a person to profess Atheism before being admitted to the National Secular Society". Bradlaugh replied that anyone could join "without being required to avow himself an Atheist". However, he added: "Candidly, we can see no logical resting-place between the entire acceptance of authority, as in the Roman Catholic Church, and the most extreme Rationalism."

Annie attended her first National Secular Society on 2nd August, 1874. "The Hall was crowded to suffocation, and, at the very moment announced for the lecture, a roar of cheering burst forth, a tall figure passed swiftly up the Hall to the platform, and, with a slight bow in answer to the voluminous greeting, Charles Bradlaugh took his seat. I looked at him with interest, impressed and surprised. The grave, quiet, stern, strong face, the massive head, the keen eyes, the magnificent breadth and height of forehead - was this the man I had heard described as a blatant agitator, an ignorant demagogue?"

Bradlaugh than began his lecture: "He began quietly and simply, tracing out the resemblances between the Krishna and the Christ myths, and as he went from point to point his voice grew in force and resonance, till it rang round the hall like a trumpet. Familiar with the subject, I could test the value of his treatment of it, and saw that his knowledge was as sound as his language was splendid. Eloquence, fire, sarcasm, pathos, passion, all in turn were bent against Christian superstition, till the great audience, carried away by the torrent of the orator's force, hung silent, breathing soft, as he went on, till the silence that followed a magnificent peroration broke the spell, and a hurricane of cheers relieved the tension".

In 1874 Bradlaugh was forty, whereas Annie was twenty-six. He was at the height of his powers and was considered to be one of the most outstanding orators in the country. Henry Snell was one of those impressed with Bradlaugh's oratory: "Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man fascinated me... and I became one of his humblest but most devoted of his followers."

Tom Mann was a young trade unionist when he first heard Bradlaugh speak: "Charles Bradlaugh was at this period, and I think for fully fifteen years, the foremost platform man in Britain. When championing an unpopular cause, it is of advantage to have a powerful physique. Bradlaugh had this; he had also the courage equal to any requirement, a command of language and power of denunciation superior to any other man of his time... He was a thorough-going Republican. Of course, in theological affairs, he was the iconoclast, the breaker of images."

Annie Besant soon became close friends with Charles Bradlaugh. A few days after their first meeting Bradlaugh offered her a job on his newspaper. "It was only a weekly salary of a guinea but it was a welcome addition to my resources". She also accepted Bradlaugh's invitation to give public lectures on subjects that she felt strongly about. In August 1874 she gave a talk entitled "The Political Status of Women" at the Co-operative Institute in London.

In her autobiography Annie Besant pointed out that she was seized by nerves right up to the moment of going on to the platform: "But to my surprise all this miserable feeling vanished the moment I was on my feet and was looking at the faces before me. I felt no tremor of nervousness from the first word to the last, and as I heard my own voice ring out over the attentive listeners I was conscious of power and of pleasure, not of fear. And from that day to this my experience has been the same; before a lecture I am horribly nervous, wishing myself at the ends of the earth, heart beating violently, and sometimes overcome by deadly sickness."

Bradlaugh's daughter commented: "She was very fluent, with a great command of language, and her voice carried well; her throat, weak at first, rapidly gained in strength, until she became a most forcible speaker. Tireless as a worker, she could both write and study longer without rest and respite than any other person I have known; and such was her power of concentration, that she could work under circumstances which would have confounded almost every other person. Though not an original thinker, she had a really wonderful power of absorbing the thoughts of others, of blending them, and of transmuting them into glowing language. Her industry, her enthusiasm, and her eloquence made of her a very powerful ally to whatever cause she espoused."

Annie Besant developed a reputation as an outstanding public speaker. The Irish journalist, T. P. O'Connor wrote: "What a beautiful and attractive and irresistible creature she was then’with her slight but full and well-shaped figure, her dark hair, her finely chiseled features… with that short upper lip that seemed always in a pout". (25) Beatrice Webb claimed that she was the "only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion." However, she added that to "see her speaking made me shudder, it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world."

Tom Mann agreed: "The first time I heard Mrs. Besant was in Birmingham, about 1875. The only women speakers I had heard before this were of mediocre quality. Mrs. Besant transfixed me; her superb control of voice, her whole-souled devotion to the cause she was advocating, her love of the down-trodden, and her appeal on behalf of a sound education for all children, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, created such an impression upon me, that I quietly, but firmly, resolved that I would ascertain more correctly the why and wherefore of her creed."

Annie and Bradlaugh became very close but they never lived together. Bradlaugh had separated from his wife but he was devoted to his two teenaged daughters, Alice and Hypatia, and was reluctant to upset them by setting up home with Annie. Friends believe that Annie was also unwilling to live with Bradlaugh while she was still officially married to Frank Besant, who was unwilling to give her a divorce.

Hypatia Bradlaugh later recalled: "They were mutually attracted; and a friendship sprang up between them of so close a nature that had both been free it would undoubtedly have ended in marriage. In their common labours, in the risks and responsibilities jointly undertaken, their friendship grew and strengthened, and the insult and calumny heaped upon them only served to cement the bond".

As Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh were atheists and republicans they came under constant attack from the newspapers. One described her as "the devil of Atheistic Freethought" and others accused the couple of believing in "free love" and the "destruction of the marriage tie". A local newspaper in Essex referred to "that bestial man and woman who go about earning a livelihood by corrupting the young of England". These accusations "horrified her Victorian conscience". Annie commented "I found myself held up to hatred as an upholder of views that I abhorred."

In reality Bradlaugh "abhorred free love as much as he worshipped free thought". According to Theodore Besterman: "There is not doubt that if they had been free Bradlaugh and Mrs Besant would have married. As it was they neither of them had the wish to indulge in an intrigue, which would, moreover, in their position, have been fatal to both of them." Another friend, Sri Prakasa, claimed that Annie Besant "was the one person who was capable of the deepest feelings without any thought of sex; and she was a woman of such remarkable courage that when she was working with colleagues she did not care what the world thought of her."

In 1832, Charles Knowlton, a doctor from Ashfield, Massachusetts, published a small pamphlet, The Fruits of Philosophy. It contained a summary of what was then known about the physiology of conception, listed a number of methods to treat infertility and impotence, and explained three methods of birth control, including a new system he had developed, that involved using a syringe to wash out the vagina after intercourse with "a solution of sulphate of zinc, of alum, pearl-ash, or any salt that acts chemically on the semen". Knowlton was arrested and was sent to prison for three months.

It was also published in Britain and over the next forty years it sold in very small numbers. A new edition was published in Bristol in December 1876, by a bookseller, Henry Cook. He was arrested and charged with publishing pornography. Cook was found guilty, and sentenced to two years' imprisonment. Charles Watts and his wife, Kate Watts, both members of the National Secular Society, decided to withdraw the pamphlet for sale in their shop in London.

Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh disagreed with this decision and decided to establish the Freethought Publishing Company so they could publish a sixpenny edition of the pamphlet. They started a major publicity campaign and on publication day, 24th March, 1877, they sold over 500 pamphlets from their small office in the first twenty minutes of it being available. A police detective was among the purchasers.

Annie wrote a preface which explained why she thought the pamphlet should be published. She referred to the Richard Carlile case in 1826 when he published Every Woman's Book. Annie stated they hoped that they could "carry on Carlile's work", a book "which argued for a rational approach to birth control, attacking the Christian demonization of sexual desire while denying the traditional chauvinist assumptions about women".

Annie Besant added that she agreed with Thomas Malthus "that population has a tendency to increase faster than the means of existence". Annie pointed out that Britain population had nearly doubled during the first half of the 19th century, growing from 11 million in 1801 to 21 million in 1851. As a result their was "enormous mortality among infants of the poor is one of the checks which now keeps down the population".

Annie went on to argue: "We think it more moral to prevent the conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air, and clothing. We advocate scientific checks to population, because, so long as poor men have large families, pauperism is a necessity, and from pauperism grow crime and disease. The wage which would support the parents and two or three children in comfort and decency is utterly insufficient to maintain a family of twelve or fourteen, and we consider it a crime to bring into the world human beings doomed to misery or to premature death".

Besant and Bradlaugh were arrested and appeared in court on 18th June, 1877. They were prosecuted by the Solicitor-General of the Conservative government, Hardinge Giffard, for publishing "a certain indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy, and obscene book". They were to be charged under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act that stated that "the test of obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall."

Giffard argued: "The truth is, those who publish this book must have known perfectly well that an unlimited publication of this sort, put into the hands of everybody, whatever their age, whatever their condition in life, whatever their modes of life, whatever their means, put into the hands of any person who may think proper to pay sixpence for it - the thesis is this: if you do not desire to have children, and wish to gratify your sensual passions, and not undergo the responsibility of marriage... It is sought to be justified upon the ground that it is only a recommendation to married people, who under the cares of their married life are unable to bear the burden of too many children. I should be prepared to argue before you that if confined to that object alone it would be most mischievous.... I deny this, and I deny that it is the purport and intention of this book."

Annie Besant later recorded in Autobiographical Sketches (1885) that Giffard used the case to attack the Liberal Party: "The Solicitor-General made a bitter and violent speech, full of party hate and malice, endeavoring to prejudice the jury against the work by picking out bits of medical detail and making profound apologies for reading them, and shuddering and casting up his eyes with the skill of a finished actor."

Annie Besant represented herself in court. She pointed out that in 1876 only 700 copies of The Fruits of Philosophy had been purchased in Britain. However, in the three months before the trial 125,000 had been sold. "My clients are scattered up and down through the length and breadth of the land; I find them amongst the poor, amongst whom I have been so much; I find my clients amongst the fathers, who see their wage ever reducing, and prices ever rising... Gentlemen, do you know the fate of so many of these children? The little ones half starved because there is food enough for two but not enough for twelve; half clothed because the mother, no matter what her skill and care, cannot clothe them with the money brought home by the breadwinner of the family; brought up in ignorance, and ignorance means pauperism and crime."

The following day in court Annie Besant illustrated the problems faced by having large families. She quoted Henry Fawcett as "children belonging to the upper and middle classes 20 per cent die before they reach the age of five"; and he adds that the amount is more than doubled in the case of children belonging to the labouring classes. "This great mortality amongst poor children is caused by neglect, by want of proper food, and by unwholesome dwellings. When we take these facts, and find that this large number of children have literally been murdered, when you consider that the number of these children who, if they had been born in a higher rank, would not have died, is calculated by Professor Fawcett as 1,150,000."

Annie Besant talked of the evils of prostitution. She believed that this problem would be reduced if young men and women married early: "I say that men and women will marry young - in the flower of their age - and more especially will this be the case amongst the poorer classes... I cannot go to the poor man, and tell him that the brightest part of his life is to be spent alone, and that he is to be shut out for years from the comforts of a home and the happiness of married life... There is no talk in this book of preventing men and women from becoming parents; all that is sought here is to limit the number of their family. And we do not aim at that because we do not love children, but, on the contrary, because we do love them, and because we wish to prevent them from coming into the world in greater numbers than there is the means of properly providing for."

The prosecutor, Hardinge Giffard, had claimed that the pamphlet was obscene because it described and illustrated "male organs of generation". However, as she pointed out, boys and girls under sixteen in government schools were using textbooks that included details of "sexual reproduction" that were much more graphic than in her pamphlet. She asked if there were any plans to prosecute the publishers of these school textbooks?

Annie Besant pointed out that her doctor provided her with a book written by Pye Henry Chavasse, entitled Advice to a Mother on the Management of Her Children and on the Treatment on the Moment of Some of Their More Pressing Illnesses and Accidents (1868). "When I was first married my own doctor gave me the work of Chavasse, on the ground that it was better for a woman to read the medical details than it was for her to have to apply to one of the opposite sex to settle matters which did not need to be dealt with by the doctor." Besant suggested that the advice given in this book was very similar to that of her own pamphlet. The difference was that Chavasse's book was expensive whereas her pamphlet cost only sixpence.

Charles Bradlaugh also carried out his own defence. He looked very closely at the economics of birth-control. "The best paid class of hewers of coal are not now averaging much more than one pound a week; take that for a man and his wife and three children only. But suppose him to have five. The Pauper Unions allow 4s 6d a week, and sometimes a little more, for boarding out a pauper child. Suppose the coalhewer has a family of five, six or seven - do the multiplication for yourselves, and leave nothing for luxury or dissipation on the part of the bread winner - I ask what means has he of purchasing the expensive treatises from which I shall quote? I now submit that it is impossible to advocate sexual restraint after marriage amongst the poor without such medical or physiological instructions as may enable them to comprehend the advocacy and utilise it."

Bradlaugh argued that using birth-control was a moral act when compared to the alternatives. He claimed that in 1868 more than 16,000 women in London "murdered their offspring". He argued, "it is amongst the poor married people that the evils of over-population are chiefly felt", and, he maintained, "the advocacy of every birth-restricting check is lawful except such as advocate the destruction of the foetus after conception or of the child after birth", and that this advocacy "to be useful must of necessity be put in the plainest language and in the cheapest form".

Alice Vickery, a nurse in London, gave evidence for the defence. She told the court "that a very great deal of suffering is caused by over-childbearing to the mothers themselves; to the children, because of the insufficient nutriment which they are able to give them and to the children before birth from the condition of the mothers." She went on to claim that mothers breast-fed their babies in an attempt to stop them getting pregnant again. "I have known many women who have continued to suckle their children as long as two years, and even longer than two years, because they believed that that would prevent them from conceiving again so rapidly." This caused serious health problems for the mothers and their babies.

Dr. Charles Robert Drysdale, Senior Physician, Metropolitan Free Hospital, also defended the actions of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. He talked in court about the medical problems caused by large families. "I have been continually obliged to lament the excessive rapidity with which the poorer classes bring unfortunate children into the world, who, in consequence, grow up weak and ricketty.... When a working man marries, the first child or two look very healthy, whilst the third will look ricketty because the mother is not able to give them that proper nourishment which she lacks herself. And so with both the fourth and fifth.... When three or four are born they get that terrible disease-the rickets - which is a great cause of death in London, a much greater cause than is generally supposed.... Hence the death-rate is largest in large families."

Drysdale then went on to look at the death-rate in London: "One fact I will mention to draw the attention of yourself and the jury to the very important point of infant mortality.... With all our advances in science we have not been able to decrease the general death-rate in London. Twenty years ago it was 22.2 per thousand persons living. In I876 it was almost exactly the same, being, in fact 22.3. Instead of dying more slowly than we did twenty years ago, we die a little faster.... The real reason of this increase in the death-rate is, that the children of the poor die three times as fast as the children of the rich... In 100,000 children of the richer classes, it was found that there were only 8,000 who died during the first year of life; whereas looking at the Registrar-General's returns we find that 15,000 out of every 1,000 of the general population die in their first year. If you take the children of the poor in the towns you will find the death-rate three times as large as among the rich - instead of 8,000 there would be 24,000 among the children of the poor. So that you see, the children of the poor are simply brought into the world to be murdered". (48)

In his final statement in court Hardinge Giffard argued: "I say that this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book to lie on his table; no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it, and yet it is to be told to me, forsooth, that anybody may have this book in the City of London or elsewhere, who can pay sixpence for it! The object of it is to enable persons to have sexual intercourse, and not to have that which in the order of Providence is the natural result of that sexual intercourse."

The jury ruled: "We are unanimously of opinion that the book in question is calculated to deprave public morals, but at the same time we entirely exonerate the defendants from any corrupt motives in publishing it." The Lord Chief Justice told the jury that the statement was unacceptable and "I must direct you on that finding, to return a verdict of guilty under this indictment against the defendants". He then turned towards Besant and Bradlaugh and said "under these circumstances, I will not pronounce sentence against you at present."

The judge eventually sentenced both of them to six months in prison and a fine of £200. However, for a sum of £500 they were allowed to have their freedom until the case appeared before the Court of Appeal. This took place in February 1878 before Lord George Bramwell, Lord William Brett and Lord Henry Cotton. They decided that the case against them was deeply flawed and the sentence was quashed.

After the court-case Besant wrote and published her own book advocating birth control entitled The Laws of Population. The idea of a woman advocating birth-control received wide-publicity. Newspapers like The Times accused Besant of writing "an indecent, lewd, filthy, bawdy and obscene book". Frank Besant used the publicity of the case to persuade the courts that he, rather than Annie Besant, should have custody of their daughter Mabel.

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws."

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him.

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the Conservative Party, warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him.

On 26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament.

The authorities attempted to obstruct the activities of Charles Bradlaugh and other freethinkers in the National Secular Society. Pamphlets on religion were seized by the Post Office and on several occasions they were excluded from using public buildings for their meetings. In 1882 the staff of the journal, The Freethinker, were prosecuted for blasphemy, and two of them were found guilty and sent to prison.

Gladstone's Affirmation Bill was discussed by Parliament in the spring of 1883. The Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal Manning, head of the Catholic Church, argued against the right of atheists to be MPs and when the vote was taken in May 1883, the Affirmation Bill was defeated. In 1884 Bradlaugh was once again elected to represent Northampton in the House of Commons. He took his seat and voted three times before he was excluded. He was later fined £1,500 for voting illegally.

Annie Besant became a socialist and started working with people such as Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and George Bernard Shaw. This upset Bradlaugh, who regarded socialism as a disruptive foreign doctrine that was based on the idea of violent revolution. This he expressed powerfully in his debate with H. M. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, in April 1884. Bradlaugh argued that as a member of the Liberal Party he believed the way forward was for the government to pass legislation to protect those suffering from poverty.

"We recognise the most serious evils, and especially in large centres of population; arising out of the poverty already existing, aggravating and intensifying the crime, disease, and misery developed from it.... I want to remedy the evil, attacking it in detail by the action of the individuals most affected by it... Social reform is one thing because it is reform; Socialism is the opposite because it is revolution... Now I have said that in order to effect Socialism in this country – and I am only dealing with this country – it would require a physical-force revolution, because you would want that physical force to make all the present property-owners who are unwilling, surrender their private property to the common fund – you would want that physical force to dispossess them."

In October, 1887, she told the readers of The National Reformer that she was now a socialist: "When I became co-editor of this paper I was not a Socialist; and, although I regard Socialism as the necessary and logical outcome of the Radicalism which for so many years the National Reformer has taught, still, as in avowing myself a Socialist I have taken a distinct step, the partial separation of my policy in labour questions from that of my colleague has been of my own making, and not of his, and it is, therefore, for me to go away. Over by far the greater part of our sphere of action we are still substantially agreed, and are likely to remain so. But since, as Socialism becomes more and more a question of practical politics, differences of theory tend to produce differences in conduct; and since a political paper must have a single editorial programme in practical politics, it would obviously be most inconvenient for me to retain my position as co-editor. I therefore resume my former position as contributor only, thus clearing the National Reformer of all responsibility for the views I hold."

Ben Tillett was a young socialist who saw her speak in London in 1887: "Mrs. Besant joined the Fabian Society very shortly after its creation, and was one of the famous group who formulated the principles of English Socialism. Her remarkable qualities as a woman, and her gifts as an orator, speedily made her a prominent figure in the East End of London, when she appeared amongst us. She spoke at our organizing meetings on several occasions. One meeting, I remember, was held in a thick fog which blotted out the faces and forms of the audience, which nevertheless stayed within hearing of Mrs. Besant's superb voice, spellbound by her eloquence and social passion".

Annie Besant joined the Social Democratic Federation and the Fabian Society. She became close to George Bernard Shaw who based the character, Raina Petkoff, in Arms and Man on Annie. A legal marriage was not possible because Frank Besant would not give her a divorce. She responded to his invitation to cohabit by producing a list of her terms for his signature. Apparently, Shaw exploded in laughter: "Good God! This is worse than all the vows of all the churches on earth. I had rather be legally married to you ten times over."

In 1887 Besant joined forces with William Stead to establish the newspaper, The Link. The halfpenny weekly carried on its front page a quotation from Victor Hugo: "I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong... I will speak for all the despairing silent ones." The newspaper campaigned against "sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution."

In June 1888, Clementina Black gave a speech on Female Labour at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, a member of the audience, was horrified when she heard about the pay and conditions of the women working at the Bryant & May match factory. The next day, Besant went and interviewed some of the people who worked at Bryant & May. She discovered that the women worked fourteen hours a day for a wage of less than five shillings a week. However, they did not always received their full wage because of a system of fines, ranging from three pence to one shilling, imposed by the Bryant & May management. Offences included talking, dropping matches or going to the toilet without permission. The women worked from 6.30 am in summer (8.00 in winter) to 6.00 pm. If workers were late, they were fined a half-day's pay.

Annie Besant also discovered that the health of the women had been severely affected by the phosphorus that they used to make the matches. This caused yellowing of the skin and hair loss and phossy jaw, a form of bone cancer. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death. Although phosphorous was banned in Sweden and the USA, the British government had refused to follow their example, arguing that it would be a restraint of free trade.

On 23rd June 1888, Besant wrote an article in her newspaper, The Link. The article, entitled White Slavery in London, complained about the way the women at Bryant & May were being treated. The company reacted by attempting to force their workers to sign a statement that they were happy with their working conditions. When a group of women refused to sign, the organisers of the group was sacked. The response was immediate; 1400 of the women at Bryant & May went on strike.

William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion of the Labour Elector and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army joined Besant in her campaign for better working conditions in the factory. So also did Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas and George Bernard Shaw. However, other newspapers such as The Times, blamed Besant and other socialist agitators for the dispute. "The pity is that the matchgirls have not been suffered to take their own course but have been egged on to strike by irresponsible advisers. No effort has been spared by those pests of the modern industrialized world to bring this quarrel to a head."

Besant, Stead and Champion used their newspapers to call for a boycott of Bryant & May matches. The women at the company also decided to form a Matchgirls' Union and Besant agreed to become its leader. After three weeks the company announced that it was willing to re-employ the dismissed women and would also bring an end to the fines system. The women accepted the terms and returned in triumph. The Bryant & May dispute was the first strike by unorganized workers to gain national publicity. It was also successful at helped to inspire the formation of unions all over the country.

The trade union leader, Henry Snell, wrote several years later: These courageous girls had neither funds, organizations, nor leaders, and they appealed to Mrs. Besant to advise and lead them. It was a wise and most excellent inspiration.... The number affected was quite small, but the matchgirls' strike had an influence upon the minds of the workers which entitles it to be regarded as one of the most important events in the history of labour organisation in any country.

In 1889 contributed to the influential book, Fabian Essays. As well as Besant, the book included articles by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

Shaw claims that "Annie Besant... was a sort of expeditionary force, always to the front when there was trouble and danger, carrying away audiences for us when the dissensions in the movement brought our policy into conflict with that of the other societies, founding branches for us throughout the country, dashing into the great strikes and free speech agitations."

In 1889 Annie Besant was elected to the London School Board in Tower Hamlets. After heading the poll with a fifteen thousand majority over the next candidate, Besant argued that she had been given a mandate for large-scale reform of local schools. Some of her many achievements included a programme of free meals for undernourished children and free medical examinations for all those in elementary schools.

In the 1890s Annie Besant became a supporter of Theosophy, a religious movement founded by Helena Blavatsky in 1875. Theosophy was based on Hindu ideas of karma and reincarnation with nirvana as the eventual aim. Besant went to live in India but she remained interested in the subject of women's rights. She continued to write letters to British newspapers arguing the case for women's suffrage and in 1911 was one of the main speakers at an important NUWSS rally in London.

While in India, Annie joined the struggle for Indian Home Rule, and during the First World War was interned by the British authorities.

Annie Besant died in India on 20th September 1933.

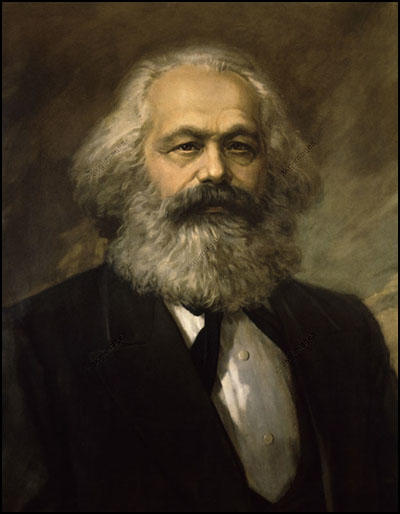

On this day in 1867 Karl Marx published Das Kapital. A detailed analysis of capitalism, the book dealt with important concepts such as surplus value (the notion that a worker receives only the exchange-value, not the use-value, of his labour); division of labour (where workers become a "mere appendage of the machine") and the industrial reserve army (the theory that capitalism creates unemployment as a means of keeping the workers in check). "The result was an original amalgam of economic theory, history, sociology and propaganda". Marx also deals with the issue of revolution. Marx argued that the laws of capitalism will bring about its destruction. Capitalist competition will lead to a diminishing number of monopoly capitalists, while at the same time, the misery and oppression of the proletariat would increase. Marx claimed that as a class, the proletariat will gradually become "disciplined, united and organised by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist production" and eventually will overthrow the system that is the cause of their suffering.

On this day in 1898 Tsar Nicholas II expels Jews from major Russian cities. In 1902 Nicholas appointed the reactionary Vyacheslav Plehve as his Minister of the Interior. Plehve's attempts at suppressing those advocating reform was completely unsuccessful. In a speech he made in 1903 Plehve argued: "Western Russia some 90 per cent of the revolutionaries are Jews, and in Russia generally - some 40 per cent. I shall not conceal from you that the revolutionary movement in Russia worries us but you should know that if you do not deter your youth from the revolutionary movement, we shall make your position untenable to such an extent that you will have to leave Russia, to the very last man!"

On this day in 1910 an explosion at the Los Angeles Times killed 21 people. Harrison Gray Otis, the owner of the newspaper was a leading figure in the fight to keep the trade unions out of Los Angeles. This was largely successful but on 1st June, 1910, 1,500 members of the International Union of Bridge and Structural Workers went on strike in an attempt to win a $0.50 an hour minimum wage. Otis, the leader of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association (M&M), managed to raise $350,000 to break the strike. On 15th July, the Los Angeles City Council unanimously enacted an ordinance banning picketing and over the next few days 472 strikers were arrested. On 1st October, 1910, a bomb exploded by the side of the newspaper building. The bomb was supposed to go off at 4:00 a.m. when the building would have been empty, but the clock timing mechanism was faulty. Instead it went off at 1.07 a.m. when there were 115 people in the building. The dynamite in the suitcase was not enough to destroy the whole building but the bombers were not aware of the presence of natural gas main lines under the building. The blast weakened the second floor and it came down on the office workers below. Fire erupted and spread quickly through the three-story building, killing twenty-one of the people working for the newspaper. John J. McNamara and James B. McNamara were eventually convicted of the bombing.

On this day in 1918 Arab forces under T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia") capture Damascus. Lawrence attended the Paris Peace Conference with Prince Feisal. He had meetings with Felix Frankfurter. His assistant, Ella Winter, recalled in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "The young, beautiful Prince Feisal was always followed by his group of tall, imposing, silent Arabs in long white robes and head dress, and by his shadow, Colonel T. E. Lawrence, also in native dress. Lawrence was short and fragile-looking, with a delicate, poetic face, but he appeared as much at home with the desert Bedouins and the prince he seemed so attached to as with European diplomats. Felix was as much intrigued by Lawrence's role in all the Middle Eastern politics as with his romantic appearance." Lawrence had been converted to the cause of the Arabs and felt they were betrayed by the treaties agreed at the Peace Conference. He was particularly concerned about the decision to give France control over Syria. He later wrote: "We lived many lives in those whirling campaigns, never sparing ourselves: yet when we achieved and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to remake in the likeness of the former world they knew."

On this day in 1932 Oswald Mosley forms the British Union of Fascists. It originally had only 32 members and included several former members of the New Party: Cynthia Mosley, Robert Forgan, William E. Allen, John Beckett and William Joyce. Mosley told them: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live."

Attempts were made to keep the names of individual members a secret but supporters of the organization included Charles Bentinck Budd, Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere), Norah Briscoe, Major General John Fuller, Jorian Jenks, Commander Charles E. Hudson, John Sidney Crosland, James Louis Crosland, Wing-Commander Louis Greig, A. K. Chesterton, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), Unity Mitford, Diana Mitford, Patrick Boyle (8th Earl of Glasgow), Malcolm Campbell and Tommy Moran. Mosley refused to publish the names or numbers of members but the press estimated a maximum number of 35,000.

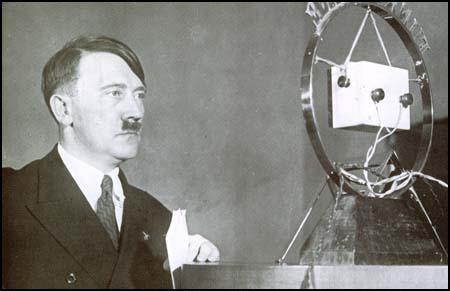

On this day in 1934 Adolf Hitler expands German army and navy, violating the Treaty of Versailles. By 1934 Hitler appeared to have complete control over Germany, but like most dictators, he constantly feared that he might be ousted by others who wanted his power. To protect himself from a possible coup, Hitler used the tactic of divide and rule and encouraged other leaders such as Hermann Goering, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Roehm to compete with each other for senior positions.

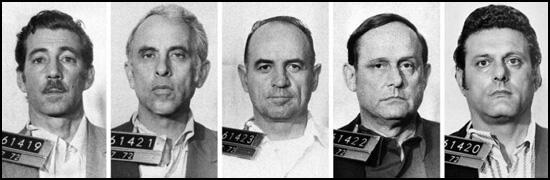

On this day in 1974 the trial of the Watergate burglars began. Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were all charged with placing electronic devices in the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. They wanted to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee and R. Spencer Oliver, executive director of the Association of State Democratic Chairmen. Later, other people closely associated with Richard Nixon, such as Gordon Liddy, John N. Mitchell, E.Howard Hunt, Jeb Magruder, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman were also tried and convicted of being involved in this crime.

On this day in 1987 Black History Month was established in the UK. It was also the the centenary of the birth of Marcus Garvey and the 25th anniversary of the Organization of African Unity, an institution dedicated to advancing the progress of African states). Black History Month in the UK was organised through the leadership of Ghanaian analyst Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, who had served as a coordinator of special projects for the Greater London Council (GLC) and created a collaboration to get it underway.

On this day in 2012, the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm. An Austrian Jew he fled to London when he was 16. He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. During this period MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded his telephone calls, intercepted his private correspondence and monitored his contacts. MI5 said the object of keeping checks on Hobsbawm was “to establish the identities of his contacts and to unearth overt or covert intellectual Communists who may be unknown to us”. Books by Hobsbawm included Primitive Rebels (1959), The Age of Revolution (1962), Labouring Men (1964), Industry and Empire (1968), Bandits (1969), Captain Swing (1969), Revolutionaries (1973), The Age of Capital (1975), History of Marxism (1978), Workers (1984), The Age of Empire (1987), Nations and Nationalism (1990), The Age of Extremes (1994), On History (1997), Uncommon People (1998), The New Century (1999), Interesting Times (2002) and Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism (2008).