On this day on 1st November

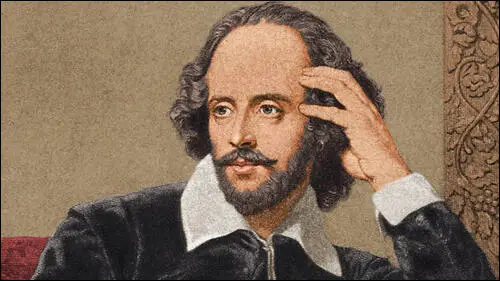

On this day in 1604 William Shakespeare's tragedy Othello is performed for the first time, at Whitehall Palace in London. His first play, Henry VI, was performed in 1592. In the next eleven years twenty-three of Shakespeare's plays were performed in London. These included Richard III, Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice, King Lear, Macbeth, and Julius Caesar.

Shakespeare wrote comedies, tragedies and history plays. He usually directed his own plays, and in some cases, even acted in them. His plays were popular with the public. The large audiences that his plays attracted enabled his theatre group to build a larger theatre called the Globe. Shakespeare's plays were also popular with the royal family. Shakespeare's group performed several of his plays in front of Elizabeth I . It is believed that Elizabeth suggested the subjects of several of the plays that he wrote.

James I also liked Shakespeare's plays. He showed his approval by allowing Shakespeare's theatre company to call themselves the King's Men. As the writer of the plays performed at the Globe, Shakespeare received a share of the theatre's profits. By 1605 he was rich enough to retire to Stratford where he died in 1616.

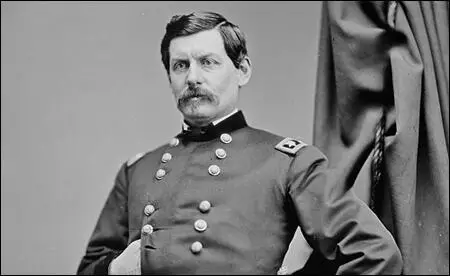

On this day in 1861 President Abraham Lincoln appointed George B. McClellan as the commander of the Union Army. Although McClellan was a member of the Democratic Party he offered his services to Lincoln on the outbreak of the American Civil War. McClellan developed a strategy to defeat the Confederate Army that included an army of 273,000 men. His plan was to invade Virginia from the sea and to seize Richmond and the other major cities in the South. McClellan believed that to keep resistance to a minimum, it should be made clear that the Union forces would not interfere with slavery and would help put down any slave insurrections.

Soon after this appointment President Lincoln ordered McClellan to appear before a committee investigating the way the war was being fought. On 15th January, 1862, McClellan had to face the hostile questioning of Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler. Wade asked McClellan why he was refusing to attack the Confederate Army. He replied that he had to prepare the proper routes of retreat. Chandler then said: "General McClellan, if I understand you correctly, before you strike at the rebels you want to be sure of plenty of room so that you can run in case they strike back." Wade added "Or in case you get scared". After McClellan left the room, Wade and Chandler came to the conclusion that McClellan was guilty of "infernal, unmitigated cowardice".

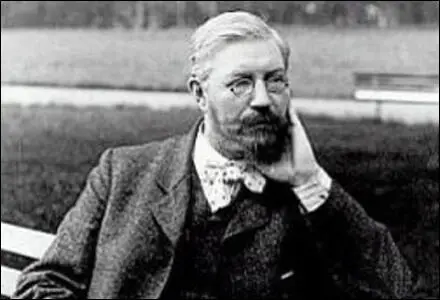

On this day in 1889 Philip Noel-Baker was born. His father, Joseph Allen Baker, was a Quaker who ran a successful machine manufacturing form. After graduating from King's College, Cambridge, he continued his education in Paris and Munich and in 1914 was appointed vice-principal of Ruskin College in Oxford. On the outbreak of the First World War, a pacifist, he became the commandant of the Friends' Ambulance Unit and served on the Western Front (1914-15) and in Italy (1915-18).

In 1918 Noel-Baker became principal assistant to Robert Cecil on the committee which drafted the League of Nations Covenant. After its formation he was a member of the Secretariat of the League as served as principal assistant to Sir Eric Drummond, the secretary-general of the League. Noel-Baker was fluent in seven languages. He was also an exceptional athlete and was captain of the British team in the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp and won the silver medal in the 1,500 metres.

Noel-Baker, a member of the Labour Party, was elected to the House of Commons in 1929. He was a member of the National Executive of the Labour Party and took a keen interest in foreign policy. In 1936 the Conservative government feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government.

Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Stanley Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Philip Noel-Baker, Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be."

During the Second World War he joined the government as parliamentary secretary to the Master of War Transport. In 1944 Noel-Baker was placed in charge of British preparatory work for the United Nations and the following year helped to draft the Charter of the UN at San Francisco. In 1946 Noel-Baker was a member of the British delegation.

In the government led by Clement Attlee Noel-Baker served as Minister of State in the Foreign Office (1945-1946), Secretary of State for Air (1946-1947), Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations (1947-1950) and Minister of Fuel and Power (1950-51).

After the Labour Party lost the 1951 General Election Noel-Baker became a member of the shadow cabinet. He also published his books, The Arms Race: A Programme for World Disarmament (1958). The following year he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

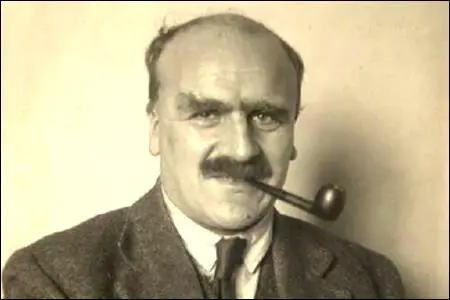

On this day in 1892 John Haldane was born. Educated at Dragon School and Eton College he won a mathematical scholarship to Oxford University and obtained a first class honours degree in 1912. He then switched to science and carried out research into genetics.

On the outbreak of the First World War Haldane joined the British Army. He was initially a Bombing Officer for the Third Battalion of the Black Watch before becoming a Trench Mortar Officer in the First Brigade. While in the army Haldane became a socialist. He wrote at the time: "If I live to see an England in which socialism has made the occupation of a grocer as honourable as that of a soldier, I shall die happy."

After the war he returned to his research at Oxford University before becoming a lecturer in Biochemistry at Cambridge University in 1922. He also conducted research on enzymes and the mathematics of natural selection and published a best-selling book called Daedalus, Or Science and The Future (1924).

In 1924 Haldane was interviewed by Charlotte Burghes, a journalist working for the Daily Express. They soon became close friends and in October 1925 they set up the Science News Service, an agency syndicating articles by them on the latest scientific discoveries. These articles appeared in national newspapers and helped to educate people about modern science.

In order to obtain a divorce from her husband, Charlotte Burghes arranged with a private detective to spend the night with John Haldane at the Adelphi Hotel in London. On 20th October 1925 Jack Burghes successfully obtained a divorce on the grounds of adultery. The case received national publicity and as a result Haldane was dismissed from his post at Cambridge University for "gross immorality". The couple were married on 11th May 1926.

Over the next few years Haldane published a series of books including Animal Biology (1927), Possible Worlds (1927) and Science and Ethics (1928). Along with his close friend, the physicist John Bernal, Haldane became convinced that the world's problems could only be solved if scientists had greater influence over government policy. He argued: "If we are to control our own and one another's actions as we are learning to control nature, the scientific point of view must come out of the laboratory and be applied to the events of daily life. It is foolish to think that the outlook which has already revolutionized industry, agriculture, war and medicine will prove useless when applied to the family, the nation, or the human race."

In 1932 Haldane was elected to the Royal Society and the following year became Professor of Genetics at University College in London. Three years later he showed the genetic link between haemophilia and colour blindness. Haldane also carried out research into how the regulation of breathing in man is affected by the level of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream. Books by Haldane during this period included The Inequality of Man (1932), Fact and Faith (1934), Heredity and Politics (1938) and Science in Everyday Life (1939).

During this period Haldane became heavily involved in left-wing politics. He was particularly concerned about the emergence of fascism in Germany and Italy. In 1933 he travelled to Spain where he gave his support to the Socialist Party (PSOE) and the Communist Party (PCE) in its struggle with the Falange Española and other extreme right-wing parties.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Haldane supported the Popular Front government and was highly critical of the British government's non-intervention policy. Haldane and his wife, Charlotte Haldane, both joined the Communist Party and were active in raising men and money for the International Brigades.

In August 1941 Charlotte Haldane began work as a war reporter in the Soviet Union the Daily Sketch. She was shocked at the level of censorship taking place under Joseph Stalin. For example, she discovered that the Russian people had not been told that England was being bombed by the Luftwaffe.

Disillusioned by what she saw in the Soviet Union, Charlotte left the Communist Party when she returned to London in November 1941. She later wrote that membership of the party and affected her journalism: "I had lied, cheated, acted under false pretenses, obeyed and carried out orders from on high, denied all my inner ethical tenets and spiritual codes for the good of the cause, convincing myself that the end justified the means."

By this time their relationship had broken down and Haldane obtained a divorce from his wife in November 1945. He remained a member of the Communist Party and was a regular contributor to the Daily Worker. In 1948 questions were asked in the House of Commons about whether communists like Haldane had access to official secrets. Haldane was quick to defend himself against these attacks. On 15th March 1948 he said: "I certainly am a Communist - as good a Communist as anyone. I am working on two Government scientific committees, one of which deals with under-water physiology. They don't pay me anything and they can throw me off them if they want to. But if they'd thrown me off six months ago, they might not have had certain increased efficiency in under-water craft. They can go on sacking people, but the only result will be that all sorts of people will be denounced as Communists when they are not. If I got orders from Moscow I would leave the Communist party forthwith."

Haldane continued to work closely with scientists in the Soviet Union. However, there was a purge of Soviet scientists after the Second World War. Haldane's great friend, Nikolai Vavilov, Head of the Institute of Genetics, was dismissed and sent to Siberia where he died. Haldane was appalled by this interference in science and in 1950 left the Communist Party.

On this day in 1894 Alexander III of Russia died. He was the second son of Tsar Alexander II and as a young man he was openly critical of his father's attempts to reform the political system. Alexander became Tsar of Russia after the assassination of his father in 1881. He immediately cancelled his father's plans to introduce a representative assembly and announced he had no intention of limiting his autocratic power.

During his reign Alexander followed a repressive policy against those seeking political reform and persecuted Jews and others who were not members of the Russian Orthodox Church. Alexander also pursued a policy of Russification of national minorities. This included imposing the Russian language and Russian schools on the German, Polish and Finnish peoples living in the Russian Empire. Despite several assassination attempts Alexander died a natural death and was succeeded by his son Nicholas II.

On this day in 1894 Nicholas II becomes the new (and last) Tsar of Russia. Nicholas inherited an empire that occupied one-sixth of the land surface of the world: "Stretching from Poland in the west of the Pacific Ocean in the east, from the Arctic Circle in the north to the Black Sea in the south, it was an area of considerable diversity in climate and landscape, and in the variety of peoples who attempted to make a living within it. The vast majority of the inhabitants were peasant farmers, living in scattered village communities."

The marriage of Nicholas II and Alexandra of Hesse-Darmstadt took place in the Grand Church of the Winter Palace of St Petersburg on 26th November 1894. Alexandra was a strong believer in the autocratic power of Tsardom and she urged him to resist demands for political reform. According to Barbara W. Tuchman, the author of The Guns of August (1962): "Though it could hardly be said that the Tsar governed Russia in a working sense, he ruled as an autocrat and was in turn ruled by his strong-willed if weak-witted wife. Beautiful, hysterical, and morbidly suspicious, she hated everyone but her immediate family and a series of fanatic or lunatic charlatans who offered comfort to her desperate soul."

On this day in 1896 Edmund Blunden was born in London. Soon afterwards the family moved to Yalding in Kent. Educated at Christ's Hospital and Queen's College, Oxford, he joined the Royal Sussex Regiment on the outbreak of the First World War.

During the war Blunden fought at Ypres and the Somme and won the Military Cross for bravery. Blunden wrote about these experiences in Undertones of War (1928). Blunden also producing collected editions of the work of the war poets, Wilfred Owen (1931) and Ivor Gurney (1954).

Blunden held several academic posts including professor of English literature at Tokyo University, University of Hong Kong and Oxford University. Blunden wrote books on Leigh Hunt, Thomas Hardy, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Charles Lamb. He also published several volumes of poetry: Pastorals (1916), The Waggoner (1920), The Shepherd (1922), English Poems (1925), Poems: 1930-40 (1941) and After the Bombing (1950). Edmund Blunden died in 1974.

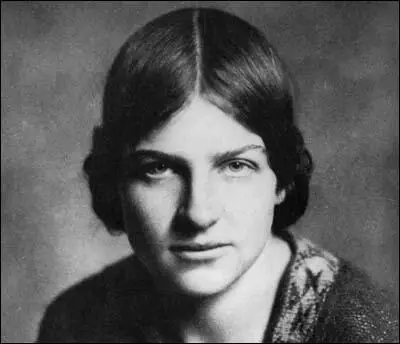

On this day in 1897 Naomi Haldane, the daughter of a physiologist, John Scott Haldane, and the sister of John Haldane, was born in Edinburgh. Her mother, Kathleen (Trotter) Haldane, was a suffragist, who published the memoir, Friends and Kindred.

After being educated at Dragon School she moved to Oxford University to science but left in 1915 to become a VAD nurse during the First World War. In 1916 she married Gilbert Mitchison, while he was on leave from the Western Front.

Naomi Mitchison was horrified by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War . A passionate supporter of the Popular Front government she wrote in 1937: "There is no question for any decent, kindly man or women, let alone a poet or writer who must be more sensitive. We have to be against Franco and Fascism and for the people of Spain, and the future of gentleness and brotherhood which ordinary men and women want all over the world."

During her life Mitchison published over 70 books. This included historical novels and short-stories such as The Conquered (1923), Cloud Cuckoo Land (1925), Black Sparta (1928), The Corn King and Queen Queen (1931) and The Blood of the Martyrs (1939).

Her novel, We Have Been Warned (1935), that dealt with abortion and birth control was censored. A socialist and active member of the Labour Party, she took part in many political campaigns, including helping her husband to get elected to the House of Commons. Mitchison was also a regular contributor to the feminist journal, Time and Tide and the New Statesman.

Mitchison, who mainly lived in Carradale on the Mull of Kintyre after 1937, wrote three volumes of memoirs, Small Talk (1973), All Change Here (1975) and You May Well Ask (1979). Her diary covering the Second World War, was published as Among You Taking Notes, was published in 1985.

Later books included a book about her travels in five continents, Mucking Around (1981), A Girl Must Live (1990) and The Oathtakers (1991).

Naomi Mitchison died, aged 101, on 11th January, 1999.

On this day in 1913 Beatrice Webb published an article where she argued that the Women's Social and Political Union has been “transformed from a passively conservative into an actively revolutionary force”.

On this day in 1916 Pavel Milyukov delivers in the State Duma the speech, precipitating the downfall of the government of Boris Stürmer. In 1905 Tsar Nicholas II faced a series of domestic problems that became known as the 1905 Revolution. This included Bloody Sunday, the Potemkin Mutiny and a series of strikes that led to the establishment of the St. Petersburg Soviet. Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia.

Sergi Witte, the new Chief Minister, advised Nicholas II to make concessions. He eventually agreed and published the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally he announced that no law would become operative without the approval of a new organization called the Duma. Milyukov now returned to Russia and established the Constitutional Democratic Party (Cadets) and represented it in the State Duma. He also drafted the Vyborg Manifesto that called for more political freedom.

On the outbreak of the First World War Milyukov began promoting patriotic policies of national defense, insisting his younger son volunteer for the army (he was later killed on the Eastern Front). In 1914 the Russian Army was the largest army in the world. However, Russia's poor roads and railways made the effective deployment of these soldiers difficult. By December, 1914, the army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. In 1915 Russia suffered over 2 million casualties and lost Kurland, Lithuania and much of Belorussia. Agricultural production slumped and civilians had to endure serious food shortages.

On 26th February 1916 Nicholas II ordered the Duma to close down. Members refused and they continued to meet and discuss what they should do. Michael Rodzianko, President of the Duma, sent a telegram to the Tsar suggesting that he appoint a new government led by someone who had the confidence of the people. When the Tsar did not reply, the Duma nominated a Provisional Government headed by Prince George Lvov. Milyukov was appointed Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Soon after taking power Milyukov wrote to all Allied ambassadors describing the situation since the change of government: "Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc." He attempted to maintain the Russian war effort but he was severely undermined by the formation of soldiers' committee that demanded "peace without annexations or indemnities".

As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) pointed out: "On the 20th April, Milyukov's note was made public, to the accompaniment of intense popular indignation. One of the Petrograd regiments, stirred up by the speeches of a mathematician who happened to be serving in the ranks, marched to the Marinsky Palace (the seat of the government at the time) to demand Milyukov's resignation." With the encouragement of the Bolsheviks, the crowds marched under the banner, "Down with the Provisional Government".

On 5th May, Milyukov and Alexander Guchkov, the two most conservative members of the Provisional Government, were forced to resign. Guchkov was now replaced as Minister of War by Alexander Kerensky. He toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. On 18th June, Kerensky announced a new war offensive. Encouraged by the Bolsheviks, who favoured peace negotiations, there were demonstrations against Kerensky in Petrograd.

At a conference of the Constitutional Democratic Party on 22nd October, 1917, Miliukov was severely criticized. Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, the author of Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia (1996) has argued that delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity. His travels abroad had made him poorly informed about the public mood, they charged; the patience of the people was exhausted." Miliukov defended his policies by arguing: "It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion.... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905."

After the Russian Revolution Milyukov advised leaders of the White Army. Following their defeat he emigrated to France, where he remained active in politics and edited the Russian-language newspaper Latest News. Several attempts were made to assassinate Milyukov. In one attempt in 1922, his friend Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, the father of famous novelist Vladimir Nabokov, was killed while with Milyukov. Pavel Milyukov died in Aix-les-Bains on 31st March 1943.

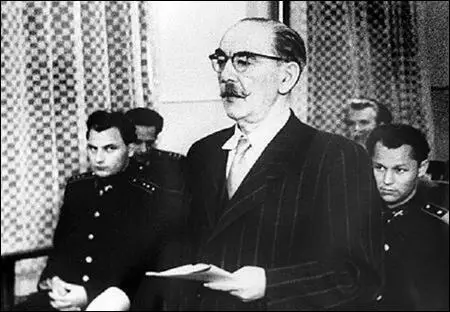

On this day in 1956 Imre Nagy announces Hungary's neutrality and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. He also asked the United Nations to become involved in the country's dispute with the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. Soviet tanks immediately captured Hungary's airfields, highway junctions and bridges. Fighting took place all over the country but the Hungarian forces were quickly defeated.

Nagy sought and obtained asylum at the Yugoslav embassy in Budapest. So also did George Lukacs, Geza Lodonczy and Julia Rajk, the widow of Laszlo Rajk. Janos Kadar, who claimed that Nagy had gone too far with his reforms, became Hungary's new leader. Janos Kadar promised Nagy and his followers safe passage out of the country. Kadar did not keep his promise and on 23rd November, 1956, Nagy and his followers, were kidnapped after leaving the Yugoslav embassy.

On 17th June 1958, the Hungarian government announced that several of the reformers had been convicted of treason and attempting to overthrow the "democratic state order" and that Imre Nagy, Pal Maleter and Miklos Gimes had been executed for these crimes.