German Resistance to Adolf Hitler: Politics and Sport

After the 1933 General Election, Chancellor Adolf Hitler proposed an Enabling Bill that would give him dictatorial powers. Such an act needed three-quarters of the members of the Reichstag to vote in its favour. All the active members of the Communist Party (KPD), were in prison, in hiding, or had left the country (an estimated 60,000 people left Germany during the first few weeks after the election). This was also true of most of the leaders of the other left-wing party, Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, Hitler still needed the support of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) to pass this legislation. Hitler therefore offered the BVP a deal: vote for the bill and the Nazi government would guarantee the rights of the Catholic Church. The BVP agreed and when the vote was taken on 24th March, 1933, only 94 members of the SDP voted against the Enabling Bill. (1)

Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party became banned organisations. Party activists still in the country were arrested. A month later Hitler announced that the Catholic Centre Party, the Nationalist Party and all other political parties other than the Nazi Party were illegal, and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp. (2)

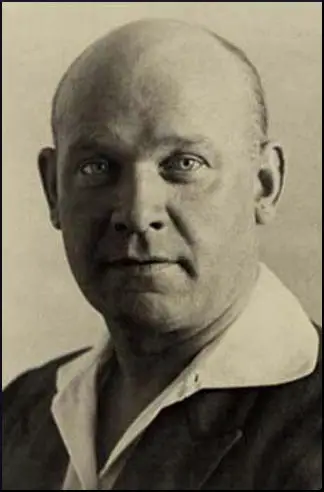

Ernst Thälmann

Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the KPD, who was arrested and imprisoned on 3rd March 1933. He managed to smuggle out details of his treatment: "It is nearly impossible to relate what happened for four and a half hours, from 5.00pm to 9.30pm in that interrogation room. Every conceivable cruel method of blackmail was used against me to obtain by force and at all costs confessions and statements both about comrades who had been arrested, and about political activities. It began initially with that friendly 'good guy' approach as I had known some of these fellows when they were still members of Severing's Political Police (during the Weimar Republic). Thus, they reasoned with me, etc., in order to learn, during that playfully conducted talk, something about this or that comrade and other matters that interested them. But the approach proved unsuccessful. Was then brutally assaulted and in the process had four teeth knocked out of my jaw. This proved unsuccessful too. By way of a third act they tried hypnosis which was likewise totally ineffective."

Thälmann went onto to point out: "But the actual high point of this drama was the final act. They ordered me to take off my pants and then two men grabbed me by the back of the neck and placed me across a footstool. A uniformed Gestapo officer with a whip of hippopotamus hide in his hand then beat my buttocks with measured strokes, Driven wild with pain I repeatedly screamed at the top of my voice. Then they held my mouth shut for a while and hit me in the face, and with a whip across chest and back. I then collapsed, rolled on the floor, always keeping face down and no longer replied to any of their questions. I received a few kicks yet here and there, covered my face, but was already so exhausted and my heart so strained, it nearly took my breath away." (3)

Wilhelm Pieck had managed to escape to the Soviet Union. In 1936 he issued a statement calling for the release of Thälmann: "If we succeeded in raising a tremendous storm of protest throughout the world, it will be possible to break down the prison walls and as in the case of Dimitrov, deliver Thälmann from the clutches of the Fascist hangmen. The fact that Ernst Thälmann has got to spend his fiftieth birthday in the gaols of Hitler-Fascism is an urgent reminder to all the anti-Fascists of the whole world that they must intensify to the utmost their campaign for the release of Thälmann and the many thousands of imprisoned victims of the White Terror." (4)

Thälmann spent the next eleven years in solitary solitary confinement. Joseph Stalin showed no real interest in trying to get him released. However, after the Soviet Union became involved in the Second World War he became an important propaganda weapon to use against Hitler: "Opposition to Europe's fascist regimes was often the only sentiment that united the Communists and Social Democrats within the anti-Nazi movement. The Comintern, the Soviet Communist Party, and the KPD sought, therefore, to use anti-fascism to create a common cause with socialists, radicals, fellow travelers, and even liberals... The communist Ernst Thälmann, who had committed no crime other than opposing Hitler, served as a key symbol in the effort to accomplish this goal." (5)

Ernst Thälmann was transferred from Bautzen Prison to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. He was executed on 18th August 1944. A few days later the Nazi government announced that Thälmann had been killed in an Allied bombing attack. "This wanton bloodshed revealed ever more clearly the unbelievably evil nature of Nazism and its Führer. It also is an indication of the increasingly desperate position of the crumbling Third Reich. Although Hitler professed to believe in ultimate victory, even he assuredly knew his Nazi empire was coming to an end." (6)

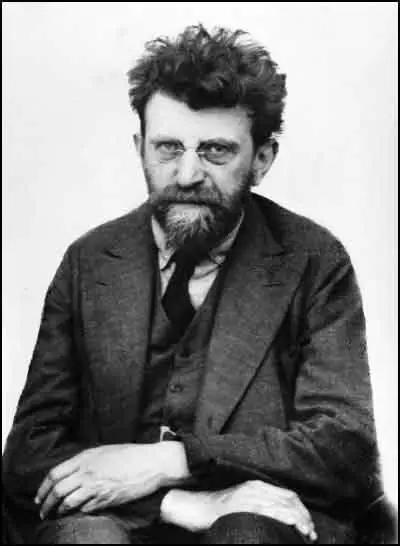

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam, the son of Siegfried Mühsam, a pharmacist, and Rosalie Seligmann, was born in Berlin on 6th April, 1878. His parents were orthodox Jews. Erich had three siblings Elisabeth Margarethe (1875), Hans Günther (1876) and Charlotte (1881). When Erich was one year old, the family moved to Lubeck, where the children were educated at local schools. (7)

As a young man he had a strong desire to become a poet: " I was completely defined by my poetry, and if my poetry was all that I had to offer to the people, then I could write an autobiography that satisfies the simple needs of literary historians for classification... Early attempts at poetry with no support from school or parents. Poetry was seen as a distraction from duty and had to be pursued in secrecy." (8)

Mühsam was expelled from school at the age of sixteen for "socialist agitation". According to the headmaster, Mühsam had leaked a speech of his to a socialist newspaper, Lübecker Volksboten (Messenger for the People): "As a consequence, the journal published a scandalous and disgraceful article about our school and a reprint of my speech, shortened, distorted, ridiculed, and with sardonic commentary - in truth, both the content and the form of the speech were noble, warm, and well measured. With this deceitful betrayal, Mühsam has placed himself beyond the school's boundaries and severed all ties with it." (9)

Following his father's wishes, Mühsam became a pharmacist apprentice. Soon after the death of his mother, he moved to Berlin. He associated with other left-wing thinkers. This included the social reformer, Heinrich Hart, who encouraged him to follow his true passion, writing, even if it brought him into conflict with his father. According to another friend, Hart argued: "If you are not afraid of a little hunger and some missteps, then go ahead and do what you have to do! How can one discourage a man from doing what he wants to?" (10)

Mühsam later argued: "Even at a young age, I realized that the state apparatus determined the injustice of all social institutions. To fight the state and the forms in which it expresses itself - capitalism, imperialism, militarism, class domination, political judiciary, and oppression of any kind - has always been the motivation for my actions. I was an anarchist before I knew what anarchism was. I became a socialist and communist when I began to understand the origins of injustice in the social fabric." (11)

Mühsam was deeply influenced by the ideas of Gustav Landauer, a leading anarchist. "Landauer was an anarchist all his life. However, it would be utterly ridiculous to read his various ideas through the glasses of a specific anarchist branch, to praise or condemn him as an individualist, communist, collectivist, terrorist, or pacifist... Landauer, never saw anarchism as a politically or organizationally limited doctrine, but as an expression of ordered freedom in thought and action." (12)

It has been argued that in the beginning, Mühsam, the younger and politically less experienced of the two, looked up to Landauer; a teacher-student dynamic long characterized their relationship. "However, Mühsam was clearly independent in his ideas and soon equaled Landauer in influence. Among the most notable differences between the two was Mühsam's openness to party communism, never shared by Landauer. There were also disparities in character: Landauer often appeared to be the philosopher and sage, while Mühsam was notoriously restless and temperamental... While Mühsam immersed himself passionately in debates about free love or the rights of homosexuals, Landauer remained cautious in these respects and always held on to marriage and family as important miniature examples of the communities on which to build a socialist society." (13)

Another friend during this period was Rudolf Rocker. He later commented on Mühsam's personality: "There was something child-like and unconstrained, something joyful in this man; something that no personal sorrow, no misery could erase. With an almost lyrical passion, he believed in the proletariat... natural desire for freedom, and whenever I challenged this assumption, it deeply upset him.... Mühsam was a believer. His belief could move mountains. He was a poet to whom there was no clear difference between the reality of life and his dreams." (14)

Augustin Souchy was another anarchist who appreciated Mühsam's talents: "He had a fascinating personality; he was spiritual, imaginative, witty, funny, and possessed a great sense of irony - at the same time he was kind, helpful, and emphatic... Erich had his heart in his hand, and comradeship in his blood." Mühsam also became friends with Frank Wedekind. One one occasion he said to Mühsam: "You always ride on two horses that pull in different directions. One day, they will tear your legs off!" Mühsam replied: "If I let go of one, I will lose my balance and break my neck." (15)

In 1908 Mühsam and Gustav Landauer established Sozialistischer Bund in May 1908, with the stated goal of "uniting all humans who are serious about realizing socialism". Landauer and Mühsam hoped to inspire the creation of small independent cooperatives and communes as the basic cells of a new socialist society. To support the new organisation, Landauer revived Der Sozialist, describing it as the Journal of the Socialist Bund. (16)

Chris Hirte has argued that the made a good combination: "To sit in a chamber and to dream of anarchist settlements, as Landauer did, was not Mühsam's way. He had to be in the midst of life; he had to be where life was at its most colorful, where things fermented and brewed." Other important members included Martin Buber and Margarethe Faas-Hardegger. At its height, they had around 800 people associated with the group. Landauer argued: "The difference between us socialists in the Socialist Bund and the communists is not that we have a different model of a future society. The difference is that we do not have any model. we embrace the future's openness and refuse to determine it. What we want is to realize socialism, doing what we can for its realization now." (17)

According to Gabriel Kuhn: "There were a few points of contention. The most important concerned matters of family life and sexuality. Laudauer, who saw the nuclear family as the social core of mutual aid and solidarity, repeatedly drew the ire of Mühsam, who was a strong believer in free love and sexual experimentation. The conflict came to a head in 1910 over the publication of Landauer's article Tarnowska, a biting critique of free love, which Landauer saw as a mere pretext for moral and social degeneration. For a while, Mühsam even saw the friendship threatened, but the two soon managed to work out their differences." (18)

Gustav Landauer also damaged his relationship with Margarethe Faas-Hardegger when he criticized her for an article questioning the nuclear family and arguing for communal child rearing. He admitted to Mühsam that "it has always been difficult for me to adopt and execute the ideas and plans for others". Mühsam pointed out: "Only those who see him as a determined and fearless fighter, kind, soft, and generous in everyday relations, but intolerant, hard, and head-strong to the point of arrogance in important issues, can understand him the way he really was." (19)

In April 1911 Mühsam established the monthly magazine Kain-Zeitschrift für Menschlichkeit (Cain - Journal for Humanity). Virtually a one man operation, the socialist journal sold well enough to guarantee Mühsam a modest living. In its first edition Mühsam wrote: "This journal has been founded without capital. Not because of any principle, but because there was no capital." (20) In his autobiography he pointed out that he was not just a journalist: "I did tedious political work like distributing leaflets and going door-to-door, and that I gave lectures at group meetings and speeches at large gatherings." (21)

On the outbreak of the First World War Mühsam controversially commented: "I am united with all Germans in the wish that we can keep foreign hordes away from our women and children, away from our towns and fields." He later apologized to his friends and admitted that he had written the words "under the pressure of anxiety, fear, mental strain, and emotional turmoil." (22) It was not long before Mühsam withdrew this statement and joined Gustav Landauer in anti-war activities. (23)

Mühsam led a very promiscuous life but he eventually became very close to Zenzl Elfinger, the daughter of an innkeeper. He wrote in his diary in December, 1914: "This morning, when she sat at my bed, I realized how dear she is to me. She comes close to what I most long for in a lover: a substitute for my mother. I can put my head in her lap and let her caress me quietly for hours. I don't feel the same with anyone else. Her love is extremely important to me, and I have to thank her more in these hard times than I sometimes realize myself. Maybe I can return some of this one day!" (24)

In July 1915, Siegfried Mühsam died. They had a very poor relationship ever since Erich Mühsam abandoned his career as a pharmacist for the life of a writer, bohemian, and political activist, but he still believed he would inherit enough money to fell financially secure. This did not happen and he wrote in his diary: "Now the whole misery starts anew - the only difference being that I will no longer be able to borrow money in the name of an impending inheritance." (25)

In September, 1915, Erich Mühsam married Zenzl Elfinger. Despite his ongoing promiscuity and related problems, she remained his lifelong companion. As a result of his anti-war activities, Mühsam was banished from Munich on 24th April 1918, to a small Bavarian town of Traunstein. On 28th October, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany. (26)

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a Council Republic. Eisner's program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. Mühsam immediately returned to Munich to take part in the revolution. Other socialists who returned to the city included Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (27)

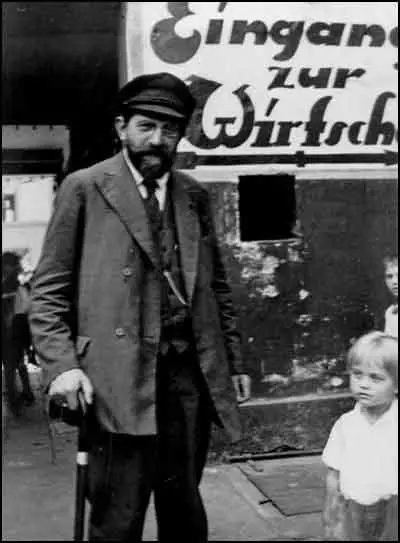

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (28)

In Bavaria, Kurt Eisner formed a coalition with the German Social Democrat Party (SDP) in the National Assembly. The Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) only received 2.5% of the total vote and he decided to resign to allow the SDP to form a stable government. He was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. (29)

It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria. One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city. (30)

Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency." (31)

On 7th April, 1919, Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A fellow revolutionary, Paul Frölich later commented: "The Soviet Republic did not arise from the immediate needs of the working class... The establishment of a Soviet Republic was to the Independents and anarchists a reshuffling of political offices... For this handful of people the Soviet Republic was established when their bargaining at the green table had been closed... The masses outside were to them little more than believers about to receive the gift of salvation from the hands of these little gods. The thought that the Soviet Republic could only arise out of the mass movement was far removed from them. While they achieved the Soviet Republic they lacked the most important component, the councils." (32)

Ernst Toller, a member of the Independent Socialist Party, became a growing influence in the revolutionary council. Rosa Levine-Meyer claimed that: "Toller was too intoxicated with the prospect of playing the Bavarian Lenin to miss the occasion. To prove himself worthy of his prospective allies, he borrowed a few of their slogans and presented them to the Social Democrats as conditions for his collaboration. They included such impressive demands as: Dictatorship of the class-conscious proletariat; socialization of industry, banks and large estates; reorganization of the bureaucratic state and local government machine and administrative control by Workers' and Peasants' Councils; introduction of compulsory labour for the bourgeoisie; establishment of a Red Army, etc. - twelve conditions in all." (33)

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Meanwhile, conditions for the mass of the population were getting worse daily. There were now some 40,000 unemployed in the city. A bitterly cold March had depleted coal stocks and caused a cancellation of all fuel rations. The city municipality was bankrupt, with its own employees refusing to accept its paper currency." (34)

Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganizing the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control. In a letter to his wife he commented that "in a few days the adventure will be liquidated". (35)

Levine pointed out that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed. (36)

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (37)

Erich Mühsam was arrested and sentenced to fifteen years of confinement in a fortress. A few weeks later, the Weimar Republic was established, giving Germany a parliamentarian constitution. Gabriel Kuhn has argued: "Being confined in a fortress - a sentence usually reserved for political dissidents - meant certain privileges compared to the general prison population, most notably the opening of cells for communal meetings and activities during the day, but it also meant increased harassment, reaching from the confiscation of papers and diaries to punishments like isolation and food deprivation. Mühsam's health deteriorated drastically during those years." (38)

While in prison Mühsam briefly joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He explained in a letter to a friend, Martin Andersen Nexø: "I recently joined the Communist Party - of course not to follow the party line, but to be able to work against it from the inside." (39) He also praised Lenin and the Bolsheviks but left the KPD when he heard about how the anarchists were being treated in Russia. (40)

Mühsam was released from prison on 20th December, 1924. He was greeted by a large gathering of sympathizers when he arrived in Berlin. The scene was later described by the journalist, Bruno Frei: "Thanks to my press card I was able to get past the police barriers. Helmet-wearing security forces, both on foot and on horses, had sealed off the station. On the square in front of it, there were several hundred, maybe a thousand workers and youths with flags and banners. Their republican deed: to greet Erich Mühsam! When the express train from Munich arrived, a few youngsters managed to make their way into the arrival hall. Mühsam stepped out of the train in obvious pain, accompanied by his wife Zenzl. The young workers lifted him on their shoulders.... Mühsam fought back tears and thanked the comrades. Someone started to sing The Internationale. At that very moment, the helmet-wearing mob attacked the people who had gathered around Mühsam. They yelled at them, pushed them, and hit them with batons. The comrades resisted courageously, though, protected Mühsam, and led him outside. Unfortunately, the police had already begun to chase the workers from the square.... Many were arrested and wounded." (41)

Mühsam established the United Front of the Revolutionary Proletariat but it eventually collapsed for lack of support. He also worked with the Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany (FKAD) but in 1925 he was expelled for carrying out "open propaganda in the interests the Communist Party" that was "not compatible with fundamental anarchist principles". Mühsam retaliated by saying that he was "an anarchist without always agreeing with the ideology and tactics of the majority of German anarchists." (42)

In October 1926 he started the journal Fanal. He argued that there was the need for a revolutionary journal that dealt with the political significance of theatre and of the arts in general. The first edition was completely written by Mühsam: "There will be no contributions from others. I was in Bavarian captivity for almost six years and practically prohibited from presenting my thoughts to a wider public... People ought to grant me the modest sixteen pages I intend to fill every month, so that finally I can propagate ideas that no one else will print." (43)

Mühsam promoted the work of left-wing artists and writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Toller, George Grosz, John Heartfield and Erwin Piscator: "Agitational art is good and necessary. It is needed by the proletariat both in revolutionary times and in the present. But it has to be art, skilled, spirited, and glittering. All arts have agitational potential, but none more than drama, In the theatre, living people present living passion. Here, more than anywhere else, true art can communicate true conviction. Here, the idea of a revolutionary worker can be materialized.... Arts must inspire people, and inspiration comes from the spirit. It is not our task to teach the minds of the workers with the help of the arts - it is our task to bring spirit to the minds of the workers with the help of the arts, as the spirit of the arts knows no limits. Neither dialectics nor historical materialism have anything to do with this; the only art that can enthuse and enflame the proletariat is the one that derives its richness and its fire from the spirit of freedom." (44)

Mühsam was an effective public speaker. Fritz Erpenbeck has argued: "He (Mühsam) was able to capture the masses. He spoke with real passion and appealed to the people's feelings... He described events with such involvement that it felt real people believed him." Rudolf Rocker wrote: "As a human being, Mühsam was one of the most beautiful people I have ever met. He belonged to no party, which means that the humanity in him had not been destroyed, as in so many others. He was always noble in his conduct, a loyal and dedicated friend, and an enormously thoughtful and entertaining host." (45)

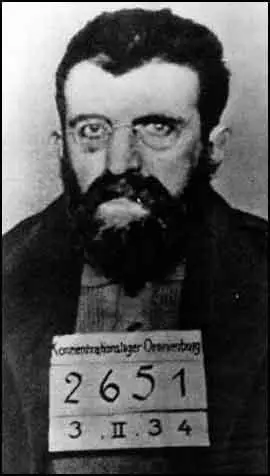

After Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, Erich Mühsam campaigned against the Nazi Party. He was arrested on 28th February, 1934 and was sent to a concentration camp in Oranienburg. His friend, Alexander Berkman, published details of his predicament: "I received a note from Germany yesterday. Erich Mühsam, the idealist, revolutionary, and Jew, represents everything that Hitler and his followers hate. They are attempting to destroy cultural and progressive life in Germany by destroying him. Mühsam became a particular object of Hitler's scorn because of his outstanding role in the Munich Revolution, alongside men like Landauer, Levine, and Toller." (46)

A fellow prisoner later recalled how Mühsam was regularly beaten: "Erich staggered, tripped over a bank, and fell on some straw mattresses. The wardens jumped after him, striking more blows. We stood still, clenching our fists and grinding our teeth, condemned to watch. We knew from experience that the slightest sign of resistance would send us to the hole for fourteen days or straight to the medical ward. Finally, the wardens pulled Erich up again and taunted him... They hit Erich again with their fists. He fell back onto the straw mattresses, the wardens followed and continued to hit and kick him." (47)

Another prisoner, John Stone, described how Erich Mühsam was murdered on 10th July, 1934: "In the evening, Mühsam was ordered to see the camp's commanders. When he returned, he said, 'They want me to hang myself - but I will not do them the favor.' We went to bed at 8 p.m., as usual. At 9 p.m., they called Mühsam from his cell. This was the last time we saw him alive. It was clear that something out of the ordinary was happening. We were not allowed to go to the latrines in the yard that night. The next morning, we understood why: we found Mühsam's battered corpse there, dangling from a rope tied to a wooden bar. Obviously, the scene was supposed to look like a suicide. But it wasn't. If a man hangs himself, his legs are stretched because of the weight, and his tongue sticks out of his mouth. Mühsam's body didn't show any of these signs. His legs were bent. Furthermore, the rope was attached to the bar by an advanced bowline knot. Mühsam knew nothing about these things and would have been unable to tie it. Finally, the body showed clear indications of recent abuse. Mühsam had been beaten to death before he was hanged." (48)

Zenzl Mühsam confirmed the death of her husband to his friend, Rudolf Rocker: "I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured. I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this? I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me." (49)

Willy Brandt

Rudolf Breitscheid was the leader of the Social Democrat Party (SDP). However, some younger members considered him too right-wing and formed the Socialist Workers Party (SAP), a Marxist left-wing organization. One of its members was Willy Brandt. When Adolf Hitler came to power members of the Socialist Workers Party were arrested by the Nazi authorities. Brandt, aged twenty, fled to Norway and after studying at Oslo University he worked as a journalist. (50)

In February 1937, Brandt traveled to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War. He based himself in Barcelona where he developed close links with the Worker's Party (POUM). While covering the war he developed a life long suspicion of communism. He later recalled how the "POUM were persecuted, dragged before the courts, or even murdered by the Communists." (51)

Brandt remained in exile during the Second World War. With the invasion of the German Army in 1940 Brandt was forced to move to Sweden. For the rest of the Second World War: He wrote to a friend: "While I have been in foreign countries, I have never tried to hide the fact that I'm a German; nor am I ashamed of it. I never hesitated about where I should go in 1933. I had been in Norway in 1931; I knew I could live there, and I wanted to. Norway has become truly my second home. In April 1940 I refused to leave Norway; I wanted to do my best for her, but sadly, there was so little that I could do. Yet my duty was to help Norway and repay my debt to her. The Nazis took away my native country from me, and Hitler took away my German citizenship. Now I have lost my homeland twice. I intend to help them to restore themselves, as a free Norway and a democratic Germany. Today, too, there are Germans fighting against Nazism in Germany. They are my friends." (52)

When Adolf Hitler gained power Rudolf Breitscheid was forced to flee to France and in 1938 helped to form the Central Union of German Emigrants. When the German Army invaded France in 1940 Breitscheild fled to Marseilles. However, in 1941 he was arrested by the Vichy government and handed over to the Gestapo. He was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. According to the Völkischer Beobachter, Breitscheid, along with Ernst Thälmann, was killed during an Allied air raid on 28th August, 1944. However, it is believed that Breitscheild was executed with Thälmann on 24th of that month. (53)

Willy Brandt returned to Germany after the war and in 1949 was elected to the Bundestag. In 1957 Brandt became a mayor of West Berlin and campaigned in favour of the removal of the Berlin Wall. He wrote to a friend: "The solution of the German problem will be dependent on decisions on an international political level. But there is much to be done inside Germany in the interests of Europe, democracy and peace. There are positive forces within the German people which will be able to make their mark on future developments. You know I have no illusions. But I wish to try to help bring Germany back into Europe.... It is fairly certain that I shall suffer disappointment and perhaps more than that. I hope I shall face defeat if it comes with the feeling that I have done my duty. I shall carry with me all the good things I have experienced in Norway." (54)

Brandt became chairman of the Social Democrat Party in 1964. Two years later he joined the coalition government led by Kurt Kiesinger. Brandt, as Foreign Minister, developed the policy of Ostpolitik (reconciliation between eastern and western Europe). George Brown pointed out: "Brandt has done things which require physical, mental and moral courage to an extent which few men could sustain. He inherited a German Social Democratic Party with very outdated traditional thinking, and requiring super-human energy and understanding to reform and revive. Like others, he had little in the way of natural advantages with which to do it. He was, of course, lucky in his colleagues but even so it was Brandt who saw the way through, not only to leading the Social Democratic Party to victory but towards uniting Europe. He is a man of shining courage - doing things which to everybody else it seemed impossible to ask a German politician to undertake. Thanks to Willy's courage and imagination, Germany may yet bring about the beginnings of a genuine détente between East and West." (55)

Brandt was a strong supporter of Britain joining the European Economic Community. In December 1967 he argued "Our own interest, which it is up to us to represent, and our understanding of the state of European interests, obliges us to speak a clear language and urge our French neighbours not to make things too difficult for themselves and others." (56) In 1969 Brandt became Chancellor of Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). He continued with his policy of Ostpolitik and in 1970 negotiated an agreement with the Soviet Union accepting the frontiers of Berlin. Later that year he signed a non-aggression pact with Poland. (57)

1936 Olympic Games

Theodor Lewald, as Reich Commissioner, was the main figure behind Germany being selected to hold the 1916 Summer Olympics. Work on the stadium, the Deutsches Stadion ("German Stadium"), began in 1912 at what was the Grunewald Race Course. On 8th June 1913, the stadium was opened. The New York Times reported: "It is estimated that 30,000 spectators were present. That structure was dedicated with almost religious fervor and military pomp. More than 30,000 men, women, and children, without pause or hitch, paraded, played games, and gave athletic drills. They represented nearly 3,000,000 members of German athletic societies." (58)

Germany was banned from taking part in the Olympic Games in 1920 (Antwerp) and 1924 (Paris). Lewald became a member of the International Olympic Committee in 1926, and successfully campaigned for Germany to be allowed to participate in the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam. In that Olympics won 31 medals (10 golds), finishing second to the United States with 56. The United Kingdom won 20 medals with only 3 golds. (59)

In 1931, Lewald was one of three German members who was able to persuade the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to hold the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The Organising Committee held its first meeting on 24th January, 1933, six days before Adolf Hitler took power. Lewald, now nearly seventy, was president of the organisation. Lewald's grandfather was Jewish and Hitler attempted to force him to resign. It was only when the International Olympic Committee threatened to take the games away from Germany, that Hitler backed down. (60)

On 1st April, 1933, the German Boxing Federation forbade Jewish boxers or referees to take part or officiate in German championship contests. Jews were expelled from all gymnastic clubs. On 2nd June, 1933, Bernhard Rust, the Minister of Education, gave instructions that Jews were to be excluded from all youth organisations. Hans von Tschammer und Osten, Reichssportführer (Reich Sports Leader) issued a declaration on behalf of the German Tennis Lawn Association stating that no Jew could be selected for the national team, and specifically that the Jewish player named Daniel Prenn would not be selected to the German Davis Cup team. As a result of this Prenn emigrated to England. (61)

Three members of the IOC, General Charles H. Sherrill, Colonel William May Garland and Commodore Ernest Lee Jahncke, complained about the way the German government was treating the Jews and threatened to withdraw the Games from Berlin. Sherrill was sent to Germany to talk to Hitler. After the meeting he sent a letter to Rabbi Stephen Wise, president of the American Jewish Congress: "It was a trying fight… The Germans yielded slowly, very slowly. First, they conceded that other nations could bring Jews. Then, after that fight was over, telephone calls came from Berlin that it should not be reported that the Government had backed-down on Jews, but only the vague statement that they agreed to follow our rules… Then I went at them hard, insisting that as they had expressly excluded Jews, now they must expressly declare the Jews not even be excluded from German teams… Finally they yielded because they found that I had lined up the necessary votes." (62)

Although some members of the IOC, like Commodore Jahncke, were serious about these complaints, General Sherrill was well known as a fascist sympathizer, with a strong desire to reach a compromise deal with Hitler. in a letter to the New York Times, he had praised Hitler as a "courageous leader". He also singled out Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator of Italy, for praise and spoke of the "amazing betterment" of life accomplished by his régime. (63)

George S. Messersmith, the United States Counsul General in Berlin, was very concerned about the dangers by the Nazi government: "I wish it were really possible to make our people at home understand how definitely this martial spirit is being developed in Germany. If this government remains in power for another year, and it carries on in the measure in this direction, it will go far toward making Germany a danger to world peace for years to come. With few exceptions, the men who are running the government are of a mentality that you and I cannot understand. Some of them are psychopathic cases and would ordinarily be receiving treatment somewhere." (64)

Messsersmith was also convinced that Hitler would not keep the promises he had made to Sherrill: "I think it should be understood that this will be merely a screen for the real discrimination which is taking place, and will be action on the part of the authorities similar to that which they took in permitting Dr von Lewald to remain on the Olympic Committee… Personalities such as Dr von Lewald in the world of sport, Dr Sauerbruch in the field of medicine, and others in various fields, are being used to endeavor to give the outside world improper or incomplete pictures of the situation here. This form of propaganda is a definite and favoured instrument of the Ministry of Propaganda." (65)

In Nazi Germany there was an increase in the persecution of Jews. In 1934 a copy of The Spirit of Sport in the National Socialist Ideology was sent to every sports club in Germany. "There is no room in our German land for Jewish sports leaders and their friends infested with the Talmud, for pacifists, political Catholics, pan-Europeans and the rest. They are worse than cholera and syphilis, much worse than famine, drought and poison gas. Do we then want to have the Olympic Games in Germany? Yes, we must have them! We think they are important for international reasons. There could not be better propaganda for Germany." (66)

Kurt Münch, the head of a new Nazi organisation called Reichdiet, produced a handbook for teachers of athletics in 1935: "Athletics and sport are the preparatory school of political driving power in the service of the State… Among the inferior races the Jews have done nothing in the athletic sphere. They are surpassed even by the lowest of the negro tribes…. German athletics are in the complete sense of the word political. It is impossible for individual or private clubs to indulge in physical exercises and games. They are the business of the State." (67)

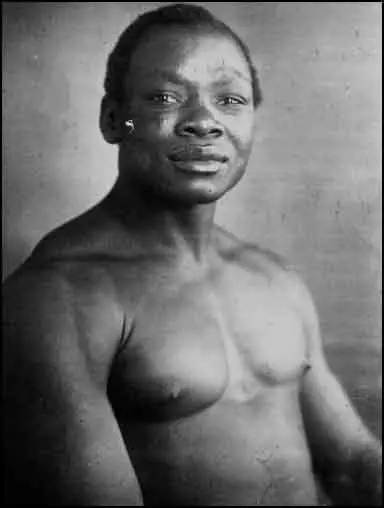

Jim Wango, a 38 year-old, black man from Nuremberg, was one of the best wrestlers in Germany. Julius Streicher, saw Wango beat a white man in March, 1935, and immediately arranged for him to be banned from taking part in tournaments. "We are in favour of sporting contests, including wrestling, in the compass of sports involving strength. What we oppose is the linking of sport with dirty business interests and sales gimmicks. It is a sales gimmick, an appeal to inferior people, to sub-humans, to put a negro on view and let him compete with white people. It is not in the spirit of the inhabitants of Nuremberg to let white men be subdued by a black man. Anyone who applauds when a black man throws a white man of our blood is no Nuremberger." (68)

Eric Phipps, the British Ambassador in Berlin, was extremely critical of the Hitler government: "Hitler's policy is simple and straightforward. If his neighbours allow him, he will become strong by the simplest and most direct methods. The mere fact that he is making himself unpopular abroad will not deter him, for, as he said in a recent speech, it is better to be respected and feared than to be weak and liked. If he finds that he arouses no real opposition, the tempo of his advance will increase. On the other hand, if he is vigorously opposed, he is unlikely at this stage to risk a break." (69)

Phipps thought it important to stop Germany from holding the Olympic Games. "The Chancellor is taking an enormous interest in the Olympic Games. In fact he is beginning to regard political questions very much from the angle of their effect on the Games.. The German Government are simply terrified lest Jewish pressure may induce the United States Government to withdraw their team and so wreck the festival, the material and propagandist value of which, they think, can scarcely be exaggerated." (70)

George S. Messersmith, the United States Counsul General in Berlin, agreed with him: "The main support of the Party from the outset has been principally among the youth, and today its actual power base is practically confined to them. This explains the really enormous interest which the Party has in the Olympic Games being held in Berlin…. To the Party and to the youth of Germany, the holding of the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936 has become the symbol of the conquest of the world by National Socialist doctrine. Should the Games not be held in Berlin, it would be one of the most serious blows which National Socialist prestige could suffer." (71)

Commodore Ernest Lee Jahncke, one of the Americans on the International Olympic Committee, was still campaigning to stop the Olympic Games from taking place in Berlin. In a letter to IOC president Henri de Baillet-Latour he argued: "Neither Americans nor the representatives of other countries can take part in the Games in Nazi Germany without at least acquiescing in the contempt of the Nazis for fair play and their sordid exploitation of the Games." (72) In July 1936, Jahncke was expelled from the IOC for his outspoken opposition and was replaced by a Nazi sympathiser, Avery Brundage, as president of the American Olympic Committee. (73)

As Carolyn Marvin, has pointed out: "The foundation of Brundage's political world view was the proposition that Communism was an evil before which all other evils were insignificant. A collection of lesser themes basked in the reflected glory of the major one. These included Brundage's admiration for Hitler's apparent restoration of prosperity and order to Germany, his conception that those who did not work for a living in the United States were an anarchic human tide, and a suspicious anti-Semitism which feared the dissolution of Anglo-Protestant culture in a sea of ethnic aspirations." (74) Brundage argued that the reason he opposed the boycott was that "the Olympic Games belong to the athletes and not to the politicians." (75)

Prior to and during the Games, there was considerable debate outside Germany over whether the competition should be allowed or discontinued. Exiled German political opponents of Hitler's regime also campaigned against the Berlin Olympics. The protests were ultimately unsuccessful; in 1935 the Amateur Athletic Union of the United States voted to compete in the Berlin Games and other countries followed suit. Forty-nine teams from around the world participated in the 1936 Games, the largest number of participating nations of any Olympics to that point. The Soviet Union was not invited but the Spanish government led by the newly elected left-wing Popular Front boycotted the Games and organized the People's Olympiad as a parallel event in Barcelona. Some 6,000 athletes from 49 countries registered. However, the People's Olympiad was aborted because of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War just one day before the event was due to start. (76) Halet Çambel and Suat Fetgeri Așani, the first Turkish and Muslim women athletes to participate in the Olympics (fencing), refused an offer by their guide to be formally introduced to Adolf Hitler, saying they would not shake hands with him due to his approach to Jews. (77)

The German Olympic committee, in accordance with Nazi directives, barred Germans who were Jewish from participating in the Games. This decision meant exclusion for many of the country's top athletes such as Gretel Bergmann who was suspended from the German team just days after she set a record of 1.60 meters in the high jump. (78) Also the shot-putter and discus thrower Lilli Henoch, who was a four-time world record holder and 10-time German national champion, Henoch died in a concentration camp in September, 1942. (79)

Brundage negotiated with the Nazis and it was agreed that Helene Mayer, who had been born in Germany and won the gold medal in the foil at the 1928 Olympics at the age of seventeen. However, after the 1932 Olympics she decided to remain in California. Although her father was Jewish, her mother was Christian, and she herself looked like an advertisement for the Aryan race, being tall, fair and beautiful. Mayer was to be the "token Jew". She was beaten in the final by Hungry’s Ilona Elek, also a Jew. The woman who came third, Ellen Preis, who had been born in Germany, but represented Austria, was also Jewish. Despite the persecution of the Jews in Germany she gave the Nazi salute during the medal ceremony. It was later claimed that she did this in order to save family members, including her mother and brothers, who were still living in Germany. (80)

Individual Jewish athletes from a number of countries chose to boycott the Berlin Olympics, including South African Sid Kiel and Americans Milton Green and Norman Cahners. Two Jewish sprinters, Martin Glickman and Sam Stoller, who did agree to go, were replaced in the American 4 x 100m relay team, at the last moment. It was afterwards claimed that the two men were dropped to please their Nazi hosts. Many Jewish athletes who competed in the Olympics would die in concentration camps during the Holocaust. Among them were Ilja Szraibman, a Polish swimmer and Roman Kantor, a Polish fencer, both of whom competed in 1936 and later died in Majdanek. (81)

American Jesse Owens won four gold medals in the sprint and long jump events. Baldur von Schirach, was with Hitler when Owens won the medals. According to Schirach, Hitler said: "The Americans should be ashamed of themselves, letting negroes win their medals for them. I shall not shake hands with this negro." Schirach pointed out that: "He is an American citizen, and its not for us to decide whom the Americans let compete. Besides, he's a friendly and educated man, a college student." Hitler replied: "Do you really think," he yelled, "that I will allow myself to be photographed shaking hands with a negro?" (82)

Despite the efforts of Owens the 1936 Olympic Games was a great success for Nazi Germany. The country won the most medals (33 gold, 25 silver and 30 bronze). Its total of 89 compared well with the 56 obtained by the United States (24 gold, 20 silver and 12 bronze). It no doubt gave Germany confidence over its two main European rivals: France 19 (7 gold, 6 silver, 6 bronze) and Britain (4 gold, 7 silver, and 3 bronze). (83)

Football and Nazi Germany

James Walvin, the author of The People's Game (1994) has argued that in the 1930s the British Foreign Office applied pressure on the Football Association to play certain foreign international games. "To a degree it is easy to understand official Foreign Office concern. In the fascist states of Germany and Italy, sport had become a crucial means of political and national expression; victories were trumpeted as political triumphs for the local nationalist system, which in their turn placed enormous emphasis on physical prowess and achievements as expressions of national character. After a fashion of course a similar ideology had underpinned the older British urge to implant athleticism throughout the world. In the 1930s, however, the stakes were more overtly political." (84)

In September, 1935, the Football Association announced that it had invited Germany to play a friendly international against England. On the 15th of that month, the pressure group, the British Anti-Nazi Council, held a protest meeting in Manchester that attracted over 3,000 people. On 28th October, there was an even larger demonstration in Hyde Park with over 20,000 people in attendance. (85) Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, made a speech where he demanded that the game should be cancelled. He went on to say that developments in Germany were dangerous to civilisation and "would lead the world to war and destruction." (86)

The British trade union movement was especially opposed to the game taking place. The Wood Green branch of the National Union of Railwaymen complained to the Home Secretary, John Simon: "I understand that the German football team propose to march through the districts of Stoke Newington and Stamford Hill with their thousands of supporters. These districts are Jewish residential areas, and such a demonstration can only lead to serious trouble… I am instructed to emphatically protest against thousands of Fascists being allowed to use this match for political propaganda, and demand that the match be banned. (87)

Walter Citrine, General Secretary of the TUC, also appealed to the Home Secretary: "The dissolution of the Trade Union and Labour Movement in Germany has produced bitter feelings among wide sections of our people, added to which the general brutal intolerance displayed by the Nazi Government has called forth world-wide condemnation…

I appeal to you to prohibit the projected football match and the visit to London of this large contingent of Nazis… Their presence in London would undoubtedly by interpreted by many people as a gesture of sympathy from the British Government to a movement whose aims and methods have evoked the strongest condemnation from every section of public opinion in the country." (88)

Simon replied to Citrine: "Wednesday’s match has no political significance whatever, and does not imply any view of either Government as to the policy or institutions of the other. It is a game of football, which nobody need attend unless he wishes, and I hope all who take an interest in it from any side will do their utmost to discourage the idea that a sporting fixture in this country has any political implications." (89)

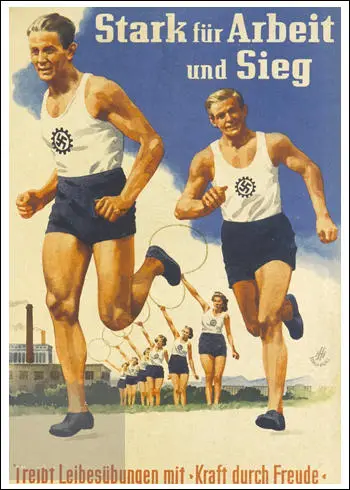

When he gained power Adolf Hitler abolished free trade unions and replaced it with the German Labour Front. On 27th November, 1933, it created Strength Through Joy (KdF). It was an attempt to organize workers' leisure time rather than allow them to organize it for themselves, and therefore enable leisure to serve the interests of the government. Robert Ley claimed that "workers were to gain strength for their work by experiencing joy in their leisure". (90) The scheme has been described as "regimented leisure" and that Hitler deemed it "necessary to control not only the working hours but the leisure hours of the individual". (91)

The most popular aspect of KdF was the provision of subsidized holidays. Large sections of the labour force were for the first time given the opportunity of holidaying away from home. It commissioned the building of two 25,000-ton purpose-built ships and chartered ten others to handle ocean cruises. In December, 1935, it arranged for 10,000 Germans to travel to London to watch their team play England at White Hart Lane. It was a curious choice of venue because within football Spurs are known as “the Jewish club” owing to support from Jewish communities in north London. There were also Jews among the players. (92)

According to one report: "No recent sporting event has been treated with such high seriousness in Germany as this match. Cheap trips to London and back - 60 marks (£3 at par) - have made it possible for 10,000 Germans to travel to England to see the match. Between 1,600 and 1,800 passengers will disembark from the Columbus at Southampton early on Wednesday morning. Three special trains will convey them to waterloo. After a trip round London and lunch, they will proceed to the football ground. Between 7,500 and 8,000 Germans will travel via Dover, and special trains will bring them to London. A description (of the game) will be broadcast throughout Germany." (93)

The Tottenham Weekly Herald joined the protests. “Letters of protest have been received by the England FA and the Spurs,” explained the article. “The Jews complain of the Nazi treatment of their compatriots in Germany and demand that the match be cancelled.” It was pointed out that Spurs had "sizeable Jewish support, and the choice of venue was insensitive, if not sinister." The Football Association replied that it was White Hart Lane’s turn for a match, regardless of opposition. The letters printed in the paper were overwhelmingly against the Jewish view: one urged them to allow English sportsmen to enjoy “their favourite pastime without interference”, while another complained: "It’s going too far when the Jews try to dictate to us. It will be the Jews who cause another war between England and Germany." Another reader wrote: "The Jews apparently do not realise they are guests in England." (94)

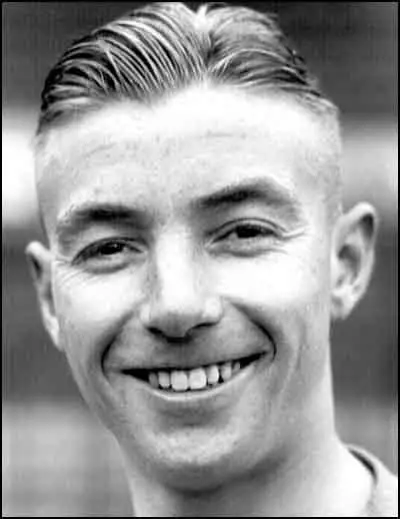

Stanley Matthews was selected to play and he later admitted that the pre-match build-up was electric... for some reason the newspapers never played up the political element. Hitler and the Nazis were in a jingoistic mood and in the early stages of their plan to conquer the world. One had a very uncomfortable feeling about Hitler and the situation over there, even in 1935. A win for Germany could boost Nazi fascism, but there was little or no mention of the political aspect to this game in the press." (95)

The match took place on the 4th December, 1935. On the day of the match a demonstration march converged on White Hart Lane. Leaflets printed in German were handed out by demonstrators and there were some minor scuffles with pro-Nazi sympathisers. The German players greeted the fans at White Hart Lane with the Nazi salute, while the Swastika fluttered alongside the Union Flag on the stadium roof. Ernie Wooley, a tool-maker from Shoreditch, climbed the flag pole and cheered on by some of the spectators, cut down the Swastika flag. (96)

The game was played in front of a 60,000 crowd. Over 800 police - mounted, on foot, as well as Special Branch members – were on duty. "A temporary police station had been set up close to the ground, while reserves were secreted in the pavilion of a neighbouring school. Policemen lined the road to the ground, while inside, they were positioned round the pitch at 10-yard intervals. Protests took place all the way from the railway stations to White Hart Lane." Protestors carried placards saying "Fascist Sport is Jew-Baiting", "Our Goal, Peace: Hitler’s Goal, War"; "Hitler Hits Below The Belt" and "Keep Sport Clean, Fight Fascism". The police treated anti-Nazis very badly and anyone shouting slogans was arrested and leaflets were grabbed and torn up. (97)

The Germans started the game very defensively, Jimmy Catton, writing in The Observer, pointed out: "Defence was their policy. They entered the arena with a conviction that they would be satisfied to draw. Eight of them were engaged in defence. The game was more like a ceremonial parade than an encounter." England attacked relentlessly and just before half-time, Middlesbrough centre-forward George Camsell controlled a long pass from Manchester City’s John Bray and fired a curling shot past Germany keeper Hans Jacob to make it 1-0. (98)

In the second-half England took control of the game. Arsenal’s Cliff Bastin dashed down the right, put in a high centre and Camsell nodded home his second. Two minutes later, Camsell returned the compliment, sliding in a ball for Bastin, who slotted home England’s third with his right foot. England won the game 3-0. Stanley Matthews was very disappointed with his performance and thought that the man who was marking him, Reinhold Münzenberg, was a great player: "Münzenberg was a watershed for me. Never in my short career had I come up against a full-back of his class... Not only was Münzenberg getting the better of me in tackles, his positioning was superb, and when it came to a chase, I was dumbfounded to find he was quicker than me. I'd never found anyone who could outpace me in domestic football. It was a shock to the system." (99)

It was reported that Hermann Göring, a leading figure in Nazi Germany, "expressed his regret his team hadn’t managed a goal, but of course, the British are in a class of themselves in football.” At a reception dinner for German officials after the match, FA president Sir Charles Clegg criticised Walter Citrine, General Secretary of the TUC, for trying to stop the match. "The sooner political bodies learn that football matches are not their business, the better it will be,” he said before toasting Adolf Hitler. (100)

Demands for the union (Anschluss) of Austria and Germany increased after Adolf Hitler gained power. In February, 1938, Hitler invited Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, to meet him at the Berghof. Hitler demanded concessions for the Austrian Nazi Party. Schuschnigg refused and after resigning was replaced by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the leader of the Austrian Nazi Party. On 13th March, Seyss-Inquart invited the German Army to occupy Austria and proclaimed union with Germany. (101)

On 3rd April 1938, the Austrian team played Germany in the Prater Stadium in Vienna its last match as an independent Austrian team. Austria's star player Matthias Sindelar, described as the "Mozart of football" was a committed socialist and an anti-Nazi and insisted that the Austrian team play in red-white-red kits (the national flag's colours) instead of their traditional white and black. (102)

According to one account: "For 69 minutes Matthias Sindelar, playing for his national side, does as he’s told. He passes up chance after chance against Germany, who just a few weeks earlier annexed his beloved Austria. This game - designed as a celebration of this ‘connection’ is an official welcoming back of Austria into the Reich. Having been advised not to score, Sindelar keeps missing the easiest of chances. Then, in the 70th minute, he tucks home a rebound - much to the surprise of the 60,000 crowd, who are fully expecting the game to fizzle out into a diplomatic 0-0 draw. Then his team-mate and friend Schasti Sesta blasts home a free-kick to make it 2-0, and the pair dance a jig of delight in front of a box full of Nazi dignitaries." (103)

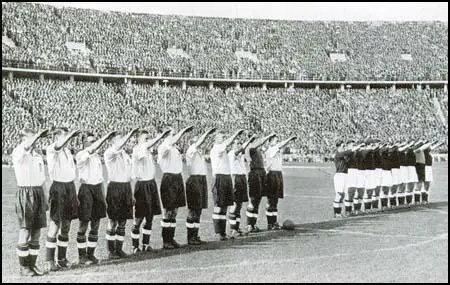

In 1938 the England team went on a tour of Europe. The first match was against Germany in Berlin on 14th May. Adolf Hitler wanted to make use of this game as propaganda for his Nazi government. Charles Wreford-Brown, the manager of the team and Stanley Rous, the Football Association secretary, had a meeting with Sir Neville Henderson the British Ambassador in Berlin, to discuss the issue of the Nazi salute. (104)

Rous suggested, as an act of courtesy, but what was more important, in order to get the crowd in a good temper, the team should give the salute of Germany before the start. Henderson agreed with this decision. However, when he gave this information to Eddie Hapgood, the captain of the team, complained: "We are of the British Empire and I do not see any reason why we should give the Nazi salute; they should understand that we always stand to attention for every National Anthem. We have never done it before - we have always stood to attention, but we will do everything to beat them fairly and squarely." (105)

While the England players were getting changed Wreford-Brown went into their dressing-room and told them that they had to give the raised arm Nazi salute during the playing of the German national anthem. Stanley Matthews later recalled: "The dressing room erupted. There was bedlam. All the England players were livid and totally opposed to this, myself included. Everyone was shouting at once. Eddie Hapgood, normally a respectful and devoted captain, wagged his finger at the official and told him what he could do with the Nazi salute, which involved putting it where the sun doesn't shine." The FA official left only to return some minutes later saying he had a direct order from the British Ambassador in Berlin. In fact, the game had been arranged on the instructions of the Conservative government as part of its appeasement policy towards Nazi Germany. The players were told that the political situation between Britain and Germany was now so sensitive that it needed "only a spark to set Europe alight". As a result the England team reluctantly agreed to give the Nazi salute. (106)

Eddie Hapgood, the captain, commented: "Well, that was that, and we were all pretty miserable about it. Personally, I felt a fool heiling Hitler, but Mr. Rous's diplomacy worked, for we went out determined to beat the Germans. And after our salute had been received with tremendous enthusiasm, we settled down to do just that. The only humorous thing about the whole affair was that while we gave the salute only one way, the German team gave it to the four corners of the ground." (107)

Matthews added that "faced with the knowledge of the direst consequences, we felt we had little choice in the matter and reluctantly agreed to the request." However, Matthews admitted: "I sat there crestfallen, thinking what on earth my family and the people back home would think if they saw me and the rest of the England team paying lip service, so to speak, to the Nazi regime and its leaders..... Faced with the knowledge of the direst consequences, we felt we had little choice in the matter and reluctantly agreed to the request. However, the game was different. We knew we had it in our power to do something about the match itself and to a man we took the field determined to do so. (108)

All of 110,000 people were crammed into the Olympic Stadium, including Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels, and they roared their approval as the German team took the field. The stadium was draped in red, black and white swastikas with a large portrait of Adolf Hitler above the stand where the Nazi leaders and dignitaries sat. Controversially, the German team included several Austrian players, "who had been absorbed into the side with the recent annexation of their country." (109) However, Austria's star player Matthias Sindelar, a well-known anti-Nazi, refused to play for Germany. Sindelar died in suspicious circumstances a few months later. (110)

According to Stanley Matthews: "From the kick-off we tore into the Germans" and Cliff Bastin gave England the lead and although Germany equalised, Mathews restored the lead. Jackie Robinson added two more and Frank Broome was on target, but it was Len Goulden of West Ham who scored the goal of the game, ten minutes from time, that made in 6-3. "We came out of defence with a series of one-touch passes that left the Germans chasing shadows before the ball was finally played out to me on the right. I took off towards Münzenberg, by now run ragged. Such was my confidence that as I ran towards him, I criss-crossed my legs over the ball as I ran and, on reaching him, swept the ball past him with the outside of my right boot and followed it. I could hear Münzenberg and the German left-half panting behind me. I glanced across and saw Len Goulden steaming in just left of the centre of midfield, some 35 yards from goal. I arced around the ball in order to get some power behind the cross and picked my spot just ahead of Len. He met the ball at around knee height. My initial thought was that he'd control it and take it on to get nearer the German goal, but he didn't. Len met the ball on the run; without surrendering any pace, his left leg cocked back like the trigger of a gun, snapped forward and he met the ball full face on the volley. To use modern parlance, his shot was like an Exocet missile. The German goalkeeper may well have seen it coming, but he could do absolutely nothing about it. From 25 yards the ball screamed into the roof of the net with such power that the netting was ripped from two of the pegs by which it was tied to the crossbar. The terraces of the packed Olympic Stadium were as lifeless as a string of dead fish." (111)

Eddie Hapgood claimed that Gouden's "terrific left foot volley from way out was one of the hardest-hit goals I've ever seen." Hapgood admitted: "I was a proud and happy man that afternoon when we trooped up the stairs, four flights, to our dressing-room after the match. In the light5 of future events, I wonder what the grim-looking, and obviously very disappointed, Nazi party officials said to their players when it was all over. Probably took their names and sent them to Russia when Germany attacked the Soviet Union!" (112)

Gottfried von Cramm

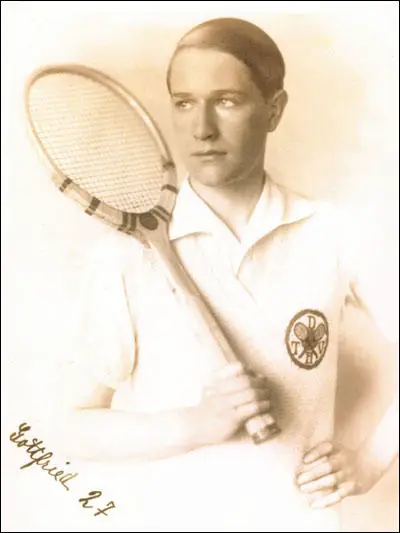

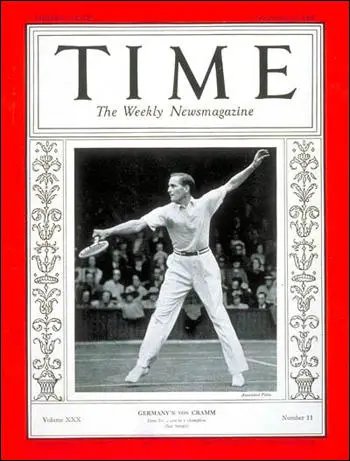

Gottfried von Cramm, the third of the seven sons of Baron Burchard von Cramm and Countess Jutta von Steinberg, was born on the family estate near Nettlingen, Lower Saxony, Germany, 7th July, 1909. (113)

The family had owned land in Lower Saxony since the 13th century and his mother was the sole heiress to the fortune of another ancient landed family. His father was very keen that his sons should be good sportsmen and he built a tennis clay court at Oelber Castle. (114)

In 1928 Von Cramm arrived in Berlin determined to become a full-time tennis player. In 1932 he won the German national tennis championship and became a member of the German Davis Cup team. He teamed up with Hilde Krahwinkel to win the 1933 Mixed Doubles title at Wimbledon. In 1934 he earned his first individual Grand Slam title by winning the French Open by beating Australian ace Jack Crawford.

According to Will Magee, "He (von Cramm) was wealthy, sociable and open-handed, while his sporting success made him wildly popular back home. He had a winning personality, as well as a reputation for good manners, sportsmanship and honourable conduct towards his opponents." Gottfried von Cramm married Elisabeth von Dobeneck in September, 1930. (115)

Gottfried von Cramm came into conflict with Adolf Hitler over his anti-Jewish policies. On 24th April 1933, Hans von Tschammer und Osten, Reichssportführer (Reich Sports Leader) issued a declaration on behalf of the German Tennis Lawn Association stating that no Jew could be selected for the national team, and specifically that the Jewish player named Daniel Prenn would not be selected to the German Davis Cup team. Von Cramm protested against this decision but he was unable to persuade Hitler to change his mind and Prenn emigrated to England. (116)

In the Davis Cup Interzone 1935 final against the Americans, during the crucial doubles match, Cramm had to carry his much weaker partner, Kai Lund, against Wilmer Allison and Johnny Van Ryn, who had won four grand slam doubles together. One newspaper described it as "the greatest one-man doubles match ever". On the fifth match point, "Gottfried served a bullet that Allison barely got back. It was a set-up at the net and Lund muffed it. He collapsed on the grass but Cramm’s expression never changed. Instead, he served another bullet which, after an exchange, Lund finally put away for the match. But not quite. The baron, the soul of chivalry, walked over to the umpire and calmly informed him that the ball had grazed his racket before his partner had put it away. Neither his opponents nor the referee had noticed. The point went to the Americans and they eventually won the match and the rubber the next day."

In the changing-room after the game, the German captain Heinrich Kleinschroth supposedly head-butted the wall of the team's changing room. Incandescent with rage, he called Gottfried von Cramm "a traitor to the nation." He replied: "Tennis is a gentleman’s game, and that’s the way I’ve played it ever since I picked up a racket. Do you think that I would sleep tonight knowing that the ball had touched my racket without my saying so? On the contrary, I don’t think I’m letting down the German people. I think I’m doing them credit." (117)

Charles Graves claimed that "Gottfried von Cramm... has the best manners on the tennis courts of any player, whether English or foreign. He always makes the most charming excuses for beaten opponents. He never loses his temper, never throws his racquet about, and, in fact, is an object-lesson in good behaviour. When he is in action, he neither grins fatuously nor scowls. No wonder the sales of the picture postcards at Wimbledon prove that he is the most popular of all the aces. He is five feet eleven and weighs exactly ten stone. He never smokes... never diets, never plays golf... shooting, fishing, hockey or swimming are another matter. Gottfried von Cramm is one of the best looking boys I have ever met. He has clear, grey-blue eyes set, in his head very much like the late T. E. Lawrence's. He talks admirable English, thanks to an English governess, has very white teeth, and blond hair brushed back." Graves also praised him for "dressing like an Englishman" and for not adopting "those appalling shorts" that some of the male competitors wearing at the time. (118)

In 1935 Gottfried von Cramm was beaten by Fred Perry in the Wimbledon final. He gained his revenge by beating Perry in the 1936 French Open. Perry beat him again at Wimbledon in 1936 and the following year he was runner-up to Don Budge. Before the game Von Cramm received a phone call from Adolf Hitler, who spent 10 minutes extolling the virtues of the Aryan race and impressing on him the necessity of measuring up to his heritage. He also won two grand slam doubles championships with Heinrich Henkel and in 1937 he was ranked as the best tennis player in the world. (119)

Gottfried von Cramm was seen as an "archetypal Aryan" and Adolf Hitler wanted to portray him as a powerful symbol by the regime. However, he disagreed with Hitler's politics and despite the pressure applied on him by Hermann Göring, he refused to join the Nazi Party. "Though he was compelled to wear tennis whites emblazoned with a swastika and to perform a Sieg Heil before the start of matches, he resisted numerous approaches to make him a central part of the Nazis' propaganda drive. While other sportsmen enthusiastically signed up to the idea of Aryan sporting supremacy, Gottfried continued to play gentlemanly tennis, and sought to get on with his life." (120)

In the summer of 1937 Germany played the United States in the Davis Cup Interzone Final. It was two matches all, and the final deciding game was between Don Budge and Von Cramm. Budge later recalled: "War talk was everywhere. Hitler was doing everything he could to stir up Germany. The atmosphere was filled with tension although Von Cramm was a known anti-Nazi and remained one of the finest gentlemen and the most popular player on the circuit." Budge said that Cramm had received a phone call from Hitler minutes before the match started and had come out pale and serious and had played "each point as though his life depended on winning". Von Cramm was ahead 4–1 in the final set when Budge launched a comeback, eventually winning 8–6 in a match considered to be one of the greatest in tennis history. (121)

According to Robert S. Wistich, this defeat "sealed Von Cramm's fate". (122) The Gestapo began to investigate Gottfried von Cramm and his family. They discovered that his wife, Elisabeth von Dobeneck, was the daughter of Robert von Dobeneck and his wife, the former Maria Hagen, a granddaughter of the Jewish banker Louis Hagen. They became suspicious when official records showed that the couple divorced in May 1937 on the grounds of "incompatibility of temperament". (123)

After further inquiries the Gestapo discovered he had been having homosexual relationships. One of his lovers was Geoffrey Nares, a young Englishman. However, it was his relationship with Manasse Herbst, a young Jewish actor, who had fled Germany in 1936, that caused the greatest concern. Soon after gaining power Hitler ordered the passing of legislation that made homosexuality illegal. On 5th March 1938, Von Cramm was arrested. The Daily Herald reported that Von Cramm had violated paragraph 175 of the Criminal Code, which covers sexual offences. However, his friends claimed that the real reason for his imprisonment was "unwise political utterances". (124)

Gottfried von Cramm was in fact charged with homosexuality and giving financial help to a Jew. While the charges were doubtlessly motivated by politics, he could not deny them as he had indeed had a homosexual relationship with Herbst and he both aided him and financed his escape to Palestine. However, he claimed that the relationship had ended before homosexuality had been banned in 1934. At a secret court he was sentenced to a year in prison. (125)

Don Budge, Joe DiMaggio, and 24 other signatories "whose names are famous in the world of lawn tennis and other sports made public an open letter demanding that the German government should immediately release and exonerate Gottfried von Cramm". The letter criticized the "dark secrecy" of the trial and denounced the charges as "mere subterfuges." It described "Baron von Cramm as an ideal sportsman, a perfect gentleman and decency personified... No country could have wished for a more creditable exponent." It added that "this darkness of silence so characteristic of dictatorships, where freedom of expression of the word or print has long ago given way to suppression of news and censorship." (126)

On his release from prison, in October, 1938, Von Cramm attempted to play tennis again. However, he was told by Erich Schönborn, the president of the German Tennis Federation, that because of his criminal record he would not be allowed to represent Germany again. On the invitation of King Gustav V he went to live in Sweden and took part in several tennis tournaments in that country.

As Von Cramm's main rivals Fred Perry, Don Budge, Bill Tilden and Ellsworth Vines, had turned professional, he was hot favourite for the 1939 Wimbledon singles championships. However, as he was still blacklisted by his own country, he had no choice but to apply as an individual (national tennis federations normally entered their players). As Marshall Jon Fisher points out: "the Wimbledon committee made up of viscounts and wing commanders and right honourables decided they could not admit a player who had been convicted of a morals charge." (127)

Gottfried von Cramm was allowed to play at Queens the week before and he beat Bobby Riggs, the winner of the Wimbledon final that year, 6-0, 6-1. Von Cramm's friend, Taki Theodoracopulos, complained that he definitely would have won the championship in 1939 if he had not been "refused entry by the cowardly All England club because of moral turpitude." (128) Elizabeth Wilson has argued in Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon (2015) that Von Cramm "was one of the greatest tennis players never to have won Wimbledon." (129)

It was later discovered that the British establishment was behind the decision not to let him play. Harold Harmsworth, the 1st Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail, and a great friend of Adolf Hitler, had put pressure on the All England Club to refuse entry into the competition. (130) Sir Louis Greig, the chairman of the All England Club at the time, like Harmsworth, a supporter of Oswald Mosley, agreed and made sure that Von Cramm did not take part in case it embarrassed Hitler. (131)

During the Second World War Gottfried von Cramm was conscripted into military service as a member of the Hermann Goering Division. Despite his background, Cramm originally served as a private soldier until being given a company to command. He saw action on the Eastern Front and was awarded the Iron Cross. His company faced harsh conditions and Cramm was flown out suffering from serious frostbite. Most of his company had been killed and, so to had two of his brothers. Not far away, at the Battle of Stalingrad, his former doubles partner, Heinrich Henkel, also was killed. (132)