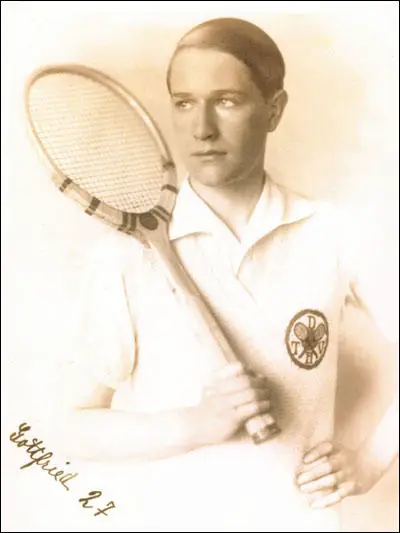

Gottfried von Cramm

Gottfried von Cramm, the third of the seven sons of Baron Burchard von Cramm and Countess Jutta von Steinberg, was born on the family estate near Nettlingen, Lower Saxony, Germany, 7th July, 1909. (1)

The family had owned land in Lower Saxony since the 13th century and his mother was the sole heiress to the fortune of another ancient landed family. His father was very keen that his sons should be good sportsmen and he built a tennis clay court at Oelber Castle. (2)

In 1928 Von Cramm arrived in Berlin determined to become a full-time tennis player. In 1932 he won the German national tennis championship and became a member of the German Davis Cup team. He teamed up with Hilde Krahwinkel to win the 1933 Mixed Doubles title at Wimbledon. In 1934 he earned his first individual Grand Slam title by winning the French Open by beating Australian ace Jack Crawford.

According to Will Magee, "He (von Cramm) was wealthy, sociable and open-handed, while his sporting success made him wildly popular back home. He had a winning personality, as well as a reputation for good manners, sportsmanship and honourable conduct towards his opponents." Gottfried von Cramm married Elisabeth von Dobeneck in September, 1930. (3)

Gottfried von Cramm came into conflict with Adolf Hitler over his anti-Jewish policies. On 24th April 1933, Hans von Tschammer und Osten, Reichssportführer (Reich Sports Leader) issued a declaration on behalf of the German Tennis Lawn Association stating that no Jew could be selected for the national team, and specifically that the Jewish player named Daniel Prenn would not be selected to the German Davis Cup team. Von Cramm protested against this decision but he was unable to persuade Hitler to change his mind and Prenn emigrated to England. (4)

In the Davis Cup Interzone 1935 final against the Americans, during the crucial doubles match, Cramm had to carry his much weaker partner, Kai Lund, against Wilmer Allison and Johnny Van Ryn, who had won four grand slam doubles together. One newspaper described it as "the greatest one-man doubles match ever". On the fifth match point, "Gottfried served a bullet that Allison barely got back. It was a set-up at the net and Lund muffed it. He collapsed on the grass but Cramm’s expression never changed. Instead, he served another bullet which, after an exchange, Lund finally put away for the match. But not quite. The baron, the soul of chivalry, walked over to the umpire and calmly informed him that the ball had grazed his racket before his partner had put it away. Neither his opponents nor the referee had noticed. The point went to the Americans and they eventually won the match and the rubber the next day."

In the changing-room after the game, the German captain Heinrich Kleinschroth supposedly head-butted the wall of the team's changing room. Incandescent with rage, he called Gottfried von Cramm "a traitor to the nation." He replied: "Tennis is a gentleman’s game, and that’s the way I’ve played it ever since I picked up a racket. Do you think that I would sleep tonight knowing that the ball had touched my racket without my saying so? On the contrary, I don’t think I’m letting down the German people. I think I’m doing them credit." (5)

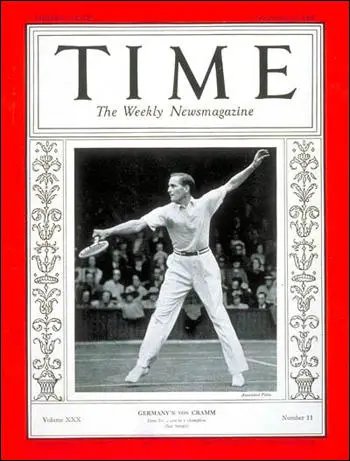

Charles Graves claimed that "Gottfried von Cramm... has the best manners on the tennis courts of any player, whether English or foreign. He always makes the most charming excuses for beaten opponents. He never loses his temper, never throws his racquet about, and, in fact, is an object-lesson in good behaviour. When he is in action, he neither grins fatuously nor scowls. No wonder the sales of the picture postcards at Wimbledon prove that he is the most popular of all the aces. He is five feet eleven and weighs exactly ten stone. He never smokes... never diets, never plays golf... shooting, fishing, hockey or swimming are another matter. Gottfried von Cramm is one of the best looking boys I have ever met. He has clear, grey-blue eyes set, in his head very much like the late T. E. Lawrence's. He talks admirable English, thanks to an English governess, has very white teeth, and blond hair brushed back." Graves also praised him for "dressing like an Englishman" and for not adopting "those appalling shorts" that some of the male competitors wearing at the time. (6)

In 1935 Von Cramm was beaten by Fred Perry in the Wimbledon final. He gained his revenge by beating Perry in the 1936 French Open. Perry beat him again at Wimbledon in 1936 and the following year he was runner-up to Don Budge. Before the game Von Cramm received a phone call from Adolf Hitler, who spent 10 minutes extolling the virtues of the Aryan race and impressing on him the necessity of measuring up to his heritage. He also won two grand slam doubles championships with Heinrich Henkel and in 1937 he was ranked as the best tennis player in the world. (7)

Gottfried von Cramm was seen as an "archetypal Aryan" and Adolf Hitler wanted to portray him as a powerful symbol by the regime. However, he disagreed with Hitler's politics and despite the pressure applied on him by Hermann Göring, he refused to join the Nazi Party. "Though he was compelled to wear tennis whites emblazoned with a swastika and to perform a Sieg Heil before the start of matches, he resisted numerous approaches to make him a central part of the Nazis' propaganda drive. While other sportsmen enthusiastically signed up to the idea of Aryan sporting supremacy, Gottfried continued to play gentlemanly tennis, and sought to get on with his life." (8)

In the summer of 1937 Germany played the United States in the Davis Cup Interzone Final. It was two matches all, and the final deciding game was between Don Budge and Von Cramm. Budge later recalled: "War talk was everywhere. Hitler was doing everything he could to stir up Germany. The atmosphere was filled with tension although Von Cramm was a known anti-Nazi and remained one of the finest gentlemen and the most popular player on the circuit." Budge said that Cramm had received a phone call from Hitler minutes before the match started and had come out pale and serious and had played "each point as though his life depended on winning". Von Cramm was ahead 4–1 in the final set when Budge launched a comeback, eventually winning 8–6 in a match considered to be one of the greatest in tennis history. (9)

According to Robert S. Wistich, this defeat "sealed Von Cramm's fate". (10) The Gestapo began to investigate Gottfried von Cramm and his family. They discovered that his wife, Elisabeth von Dobeneck, was the daughter of Robert von Dobeneck and his wife, the former Maria Hagen, a granddaughter of the Jewish banker Louis Hagen. They became suspicious when official records showed that the couple divorced in May 1937 on the grounds of "incompatibility of temperament". (11)

After further inquiries the Gestapo discovered he had been having homosexual relationships. One of his lovers was Geoffrey Nares, a young Englishman. However, it was his relationship with Manasse Herbst, a young Jewish actor, who had fled Germany in 1936, that caused the greatest concern. Soon after gaining power Hitler ordered the passing of legislation that made homosexuality illegal. On 5th March 1938, Von Cramm was arrested. The Daily Herald reported that Von Cramm had violated paragraph 175 of the Criminal Code, which covers sexual offences. However, his friends claimed that the real reason for his imprisonment was "unwise political utterances". (12)

Gottfried von Cramm was in fact charged with homosexuality and giving financial help to a Jew. While the charges were doubtlessly motivated by politics, he could not deny them as he had indeed had a homosexual relationship with Herbst and he both aided him and financed his escape to Palestine. However, he claimed that the relationship had ended before homosexuality had been banned in 1934. At a secret court he was sentenced to a year in prison. (13)

Don Budge, Joe DiMaggio, and 24 other signatories "whose names are famous in the world of lawn tennis and other sports made public an open letter demanding that the German government should immediately release and exonerate Gottfried von Cramm". The letter criticized the "dark secrecy" of the trial and denounced the charges as "mere subterfuges." It described "Baron von Cramm as an ideal sportsman, a perfect gentleman and decency personified... No country could have wished for a more creditable exponent." It added that "this darkness of silence so characteristic of dictatorships, where freedom of expression of the word or print has long ago given way to suppression of news and censorship." (14)

On his release from prison, in October, 1938, Von Cramm attempted to play tennis again. However, he was told by Erich Schönborn, the president of the German Tennis Federation, that because of his criminal record he would not be allowed to represent Germany again. On the invitation of King Gustav V he went to live in Sweden and took part in several tennis tournaments in that country.

As Von Cramm's main rivals Fred Perry, Don Budge, Bill Tilden and Ellsworth Vines, had turned professional, he was hot favourite for the 1939 Wimbledon singles championships. However, as he was still blacklisted by his own country, he had no choice but to apply as an individual (national tennis federations normally entered their players). As Marshall Jon Fisher points out: "the Wimbledon committee made up of viscounts and wing commanders and right honourables decided they could not admit a player who had been convicted of a morals charge." (15)

Gottfried von Cramm was allowed to play at Queens the week before and he beat Bobby Riggs, the winner of the Wimbledon final that year, 6-0, 6-1. Von Cramm's friend, Taki Theodoracopulos, complained that he definitely would have won the championship in 1939 if he had not been "refused entry by the cowardly All England club because of moral turpitude." (16) Elizabeth Wilson has argued in Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon (2015) that Von Cramm "was one of the greatest tennis players never to have won Wimbledon." (17)

It was later discovered that the British establishment was behind the decision not to let him play. Harold Harmsworth, the 1st Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail, and a great friend of Adolf Hitler, had put pressure on the All England Club to refuse entry into the competition. (18) Sir Louis Greig, the chairman of the All England Club at the time, like Harmsworth, a supporter of Oswald Mosley, agreed and made sure that Von Cramm did not take part in case it embarrassed Hitler. (19)

During the Second World War Gottfried von Cramm was conscripted into military service as a member of the Hermann Goering Division. Despite his background, Cramm originally served as a private soldier until being given a company to command. He saw action on the Eastern Front and was awarded the Iron Cross. His company faced harsh conditions and Cramm was flown out suffering from serious frostbite. Most of his company had been killed and, so to had two of his brothers. Not far away, at the Battle of Stalingrad, his former doubles partner, Heinrich Henkel, also was killed. (20)

According to Richard K. Mastain, the author of The Old Lady of Vine Street (2009) Gottfried von Cramm was involved in the July Plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Lieutenant-Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg planted the bomb on 20th July, 1944. but it failed to kill Hitler. If the attempt had been successful the plan was for Von Cramm to go to Sweden and negotiate a surrender with the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden. (21)

After the war Gottfried von Cramm returned to playing tennis. He won the German national championship in 1948 and again in 1949, when he was 40 years old. Von Cramm went on playing Davis Cup tennis until retiring after the 1953 season and still holds the record for the most wins by any German team member. Following his retirement from active competition, Cramm served as an administrator in the German Tennis Federation and became successful in business as a cotton importer. (22)

In November, 1955, Gottfried von Cramm married Barbara Hutton, an American socialite and an heiress to the Woolworth fortune. Von Cramm was Hutton's sixth husband and told the press: "We should have married eighteen years ago. We fell in love after our first meeting at Cairo in 1937, but somehow it never happened." (23) He later admitted that he had married her in order to "help her through substance abuse and depression but was unable to help her in the end." They were divorced in 1959. (24)

Baron Gottfried von Cramm, aged 66, died in an automobile accident on a desert road in Egypt on a return trip from Alexandria on business on 8th November, 1976.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Graves, The Bystander (8th July, 1936)

Gottfried von Cramm, who beat Fred Perry in the French Championship only six weeks ago, has the best manners on the tennis courts of any player, whether English or foreign. He always makes the most charming excuses for beaten opponents. He never loses his temper, never throws his racquet about, and, in fact, is an object-lesson in good behaviour. When he is in action, he neither grins fatuously nor scowls. No wonder the sales of the picture postcards at Wimbledon prove that he is the most popular of all the aces.

He is five feet eleven and weighs exactly ten stone. He never smokes... never diets, never plays golf... shooting, fishing, hockey or swimming are another matter. Gottfried von Cramm is one of the best looking boys I have ever met. He has clear, grey-blue eyes set, in his head very much like the late T. E. Lawrence's. He talks admirable English, thanks to an English governess, has very white teeth, and blond hair brushed back. He dresses like and Englishman, enjoys life and, thank goodness, refuses absolutely to wear those appalling shorts which Tom Webster guys so unmercifully and deservedly.

(2) The Daily Herald (4th May, 1938)

The trial of Baron Gottfried von Cramm, Germany's number one tennis player, will begin on May 14. When Von Cramm was arrested in March, violation of paragraph 175 of the Criminal Code, which covers sexual offences was mentioned. "Unwise political utterances" were also rumoured.

(3) Will Magee, Life, Death, Tennis and the Nazis: Gottfried von Cramm, The Man That Wimbledon Forgot (30th June, 2016)

When tennis fans in this country think of the 1936 Wimbledon men's final, they associate it first and foremost with Fred Perry. It's a final that holds a significant place in the national consciousness because, prior to Andy Murray's triumph in 2013, it represented the last time a British man had won Wimbledon. Perry was brought up relentlessly during the Tim Henman era, and became yet another stick with which to beat the nation's perennial also-ran. In the end, it took 77 years for Perry's Wimbledon heroics to be matched by a British sportsman. For almost eight decades, tennis on these shores was forever looking back to the summer of 1936.

That said, there has never been much attention given to Perry's opponent in that fateful final. When Perry went over to the net at the end of the three-set thrashing, he shook hands with a tall, blonde gentleman; a man with gentle, handsome features as well as remarkable sinew and strength. That man was Gottfried von Cramm, one of the greatest ever German tennis players. He was a supreme athlete, but also a man conflicted. Rightly admired as a great sportsman, he was also one of the most interesting characters ever to take to the court.

Gottfried truly announced himself to the world of tennis in 1934, when he beat Australian ace Jack Crawford and won Roland Garros. Though he had won the German national championships previously, that represented his first Grand Slam. His background piqued contemporary interests, not least because of his nationality and the feverish political situation in Germany at the time.

Gottfried was a Saxon aristocrat, the third son of Burchard Baron von Cramm. He was wealthy, sociable and open-handed, while his sporting success made him wildly popular back home. He had a winning personality, as well as a reputation for good manners, sportsmanship and honourable conduct towards his opponents. Though it was only whispered at the time of his first Grand Slam, he was also gay, and in a discreet relationship with Manasse Herbst, a young actor and Galician Jew.

In the Germany of 1934, that relationship was seriously problematic. Adolf Hitler had consolidated his power as Führer, and it would be barely a year before homosexuality was criminalised in law. Jewish citizens were already subjected to discrimination, hatred and violence, and fear was beginning to grip their community. It was in this context that Gottfried von Cramm became one of Germany's most celebrated athletes, and so was asked to represent a country that was quickly sinking into the totalitarian abyss.

Blonde, chiselled and archetypal Aryan, Gottfried was seen as a powerful symbol by the regime. Owing to his own circumstances and convictions, however, he was steadfastly unwilling to play the role required. Though he was compelled to wear tennis whites emblazoned with a swastika and to perform a Sieg Heil before the start of matches, he resisted numerous approaches to make him a central part of the Nazis' propaganda drive. While other sportsmen enthusiastically signed up to the idea of Aryan sporting supremacy, Gottfried continued to play gentlemanly tennis, and sought to get on with his life.

Tension between Gottfried and the regime grew steadily after the Davis Cup final of 1935, which Germany lost to the USA. He refused to take match point in the deciding game of the match, after informing the umpire that the ball had tipped his racket during the rally. Nobody had seen the error but, nonetheless, Gottfried indicated that a point should be called against him. Germany went on to lose, and the blame fell directly on to the shoulders of the honourable Von Cramm.

After that match, Germany captain Heinrich Kleinschroth supposedly headbutted the wall of the team's changing room. Incandescent with rage, he called Von Cramm "a traitor to the nation." Gottfried's reply epitomised his character. "On the contrary, I don't think that I've failed the German people," he said. "In fact, I think I've honoured them." The authorities saw the defeat rather differently, and there was increased pressure on him to conform.

Gottfried repeatedly refused to join the Nazi Party, despite the menacing insistence of, amongst others, Hermann Göring. Not only did he despise their discriminative policies, he also resented them for the exile of Polish Jew and former teammate Daniel Prenn. Anecdotally, it has been suggested that Von Cramm used to refer to Hitler as "the house painter", a jibe at the Führer's early years as a failed artist in Vienna. This was a dangerous attitude to take in Nazi Germany, especially for a gay man with the eyes of the nation upon him.

Despite all this, Von Cramm continued to excel on the court. He triumphed at the French Championships once again in 1936, and won the men's doubles at both Roland Garros and the US Open alongside his protégé, Heinrich Henkel, the year afterwards. His most famous exploits were at Wimbledon, however. Though he never won the tournament, his performances at the All England Club earned him praise the world over.

Gottfried was runner-up at Wimbledon for three years running, losing the first and second matches to Fred Perry in 1935 and '36, and the third to American tennis legend Don Budge in '37. While he lost all three matches in straight sets, he did so against the undisputed superstars of the day, and did himself great credit in the process. What's more, his first match against Perry and his last against Budge have gone down in history as legitimate classics, having featured some of the best, most entertaining tennis of the era.

As the political situation in Europe deteriorated and World War II loomed ever larger, the tense relationship between Von Cramm and the Nazis rapidly broke down. Before an infamous match with Budge at the 1937 Davis Cup, it was rumoured that Gottfried had received a call from Hitler ordering him to claim victory at all costs. He went 4-1 ahead in the final set, only to let his lead slip and end up losing 8-6. While Budge sympathised with his anxious, burdened opponent, the regime did not.

On 5 March 1938, two Gestapo agents barged in on a Von Cramm family dinner. Gottfried was summarily arrested, and imprisoned at the leisure of the German government. He was charged with homosexuality and giving financial help to a Jew. While the charges were doubtlessly motivated by politics, he could not deny them. Manasse Herbst had fled the country for Palestine in 1936, and Von Cramm had both aided him and financed his escape.

Gottfried admitted the relationship to the authorities, and was sentenced to a year in prison. His lawyer managed to lessen the severity of the punishment by claiming that Herbst had blackmailed him into sending the money, as he was "a sneaky Jew". This was a ploy, and the fact that Von Cramm hosted Herbst after the war attests to their enduring friendship. Had it not been for Gottfried's money, it is quite possible that Herbst would not have survived the horrors to come.

As a man with many friends in tennis, several high-profile players leapt to Von Cramm's defence. Complaints were lodged to the German authorities, while Don Budge collected the signatures of his fellows professionals before sending a letter of protest to Hitler. Unfortunately, the tennis hierarchy was far less understanding. After Von Cramm's early release in early 1939, he was ostracized by the All England Club. The political climate was doubtlessly the main factor in his exclusion from Wimbledon that year, but the official pretext was that he was a convicted criminal, and therefore unfit to grace the grass.

(4) Taki Theodoracopulos, The Spectator (2nd September, 2009)

Von Cramm was born into a very ancient aristocratic German family, and his devastating good looks, as well as his unparalleled sportsmanship, made him an idol both in Germany and Britain. He reached the final at Wimbledon three times, losing all three matches (although in his second final he had pulled a muscle and should have defaulted but gallantly refused to do so). Gottfried won the French Championships twice in a row, the slow clay being perfect for his beautiful flat strokes and devastating second spin serve. Cramm was known for never, ever glancing at a linesman after a bad call - or disputing a call, for that matter. In the Davis Cup Interzone 1935 final against the Americans, during the crucial doubles match, Cramm had performed miracles, carrying his much weaker partner, Kai Lund, against the formidable Wimbledon winners Wilmer Allison and Johnny Van Ryn. The papers called it "the greatest one-man doubles match ever". On the fifth match point, Gottfried served a bullet that Allison barely got back. It was a set-up at the net and Lund muffed it. He collapsed on the grass but Cramm’s expression never changed. Instead, he served another bullet which, after an exchange, Lund finally put away for the match. But not quite. The baron, the soul of chivalry, walked over to the umpire and calmly informed him that the ball had grazed his racket before his partner had put it away. Neither his opponents nor the referee had noticed. The point went to the Americans and they eventually won the match and the rubber the next day.

In the locker room afterwards, a German official had a nervous breakdown. He reminded Gottfried that Germany had never come as close to winning the cup - far more prestigious than any championship back then - and charged von Cramm with letting down the side. Here’s the baron’s reply: "Tennis is a gentleman’s game, and that’s the way I’ve played it ever since I picked up a racket. Do you think that I would sleep tonight knowing that the ball had touched my racket without my saying so? On the contrary, I don’t think I’m letting down the German people. I think I’m doing them credit." All this in a calm, composed and elegant manner. The listening Americans were dumbfounded. Then they cheered.

After his defeat against Budge in the Wimbledon final of 1938, the baron, who was married to the beautiful Lisa von Dobeneck, was charged by the Nazis with homosexuality and was sent to a concentration camp for a year. Von Cramm was homosexual but one would never have known it by his behaviour, which was that of an impeccable gentleman. In 1939, with Cramm the hot favourite finally to win the Wimbledon final (he had beaten the eventual winner Bobby Riggs 6-0, 6-1 at Queens the week before), he was refused entry by the cowardly All England club because of moral turpitude, a Nazi invention as no one had ever come forward to accuse Cramm of anything resembling public lewdness. Worse, Cramm was refused entry by the United States until his death in 1976 because of a Nazi charge.

Two of Gottfried’s brothers were killed on the Russian front, where he served and won the military cross for valour. He played Wimbledon well into his forties, as well as the Davis Cup, and was killed in a car crash in Cairo in 1976. His widow was Barbara Hutton, the original poor little rich girl.

In today’s barbarian sport culture, where overpaid, steroid-sodden freaks perform like trained seals, Gottfried’s aristocratic looks, brilliant strokes and impeccable sportsmanship may look almost counterproductive, but the opposite is true. Both Budge and he died in car accidents, but their 1937 match will live for ever for its brilliance as well as for its drama. "Thank you, Don, for making me play the best tennis of my life," said Cramm as he went to the net to congratulate Budge. Some loser. Hitler is still turning over about that one.

(5) Deane MeGowen, New York Times (10th November, 1976)

Baron Gottfried von Cramm, German tennis star of the 1930's, died in an automobile accident today on a desert road on a return trip from Alexandria on business. He was 66 years old.

The West German Embassy said his car and a truck had collided about 20 miles outside Cairo. The driver of his car also was killed. There were no other immediate details.

Baron Gottfried von Cramm's position in the world of international tennis is secure. The German star came to be known in the twilight of Bill Tilden's career, and played against such greats as Fred Perry of Britain and Don Budge of the United States,

He was a socialite, a member of prominent family who vowed that he would never turn professional ("They won't catch me, no matter what they propose"), a World War II veteran, the sixth husband of Barbara Hutton, the five and dime heiress from whom he was later divorced, and an alleged victim ot Nazi intrigue.

His tennis career stretched from 1930 to 1953, during which he won 82 of 102 Davis Cup matches. He won the French singles title in 1934 and 1936 and held the German championship from 1932 to 1935. After the war he captured the West German singles title in 1948 and 1949.

It was perhaps his misfortune to come into prominence at the time of Perry and Budge. He lost in the final at Wimbledon to Perry in 1935 and 1936 and to Budge in 1937. His only Wimbledon championship came in 1933, when he and Hilda Krahwinkel took the mixed doubles.

Tennis historians regard his Davis Cup interzone match against Budge at Wimbledon in July 1937 as one of the greatest court duels. Von Cramm, playing brilliantly, took the first two sets, but the California redhead recovered and finally won, 6-8, 5-7, 6-4, 6-2, 8-6. in the fifth set von Cramm fought off five match points before yielding.

(6) Mandrake, The New European (13th April, 2018)

Just as the Daily Mail was pointing an accusing finger at Jeremy Corbyn over anti-Semitism, Adolf Hitler’s ghost came back to haunt the newspaper that had once notoriously been his principal cheerleader on Fleet Street.

Mandrake hears that its executives had commissioned a piece about Baron Gottfried von Cramm, the world number one tennis player before the Second World War, whose life is to be celebrated in a major feature film called Poster Boy.

It was set to run across two pages, until someone noticed a few paragraphs that documented how the All England Club had colluded with the Nazis in banning the dashing German player from the 1939 Wimbledon tournament, even though he was favourite to win.

Awkwardly, the prime mover in getting him banned had been the man who then owned the Daily Mail, Harold, the first Viscount Rothermere, who was a big noise in the club and a devoted fan of the Führer.

Indeed, Rothermere had called him “Adolf the Great,” saw to it he was lauded to the skies in his own paper and had inevitably been incensed that von Cramm had seen fit to publicly criticise his idol. “There had obviously been no mention of Harold in the piece, but let us say there is an acute awareness of our owner’s family history,” whispers my nark in the newsroom. “The piece was referred upwards and duly spiked.”

(7) Mandrake, The New European (20th April, 2018)

Whether it’s 1939 or 2016, one newspaper can always be relied upon to be on the wrong side of the argument.

It’s no surprise that the Daily Mail got it wrong about both Adolf Hitler and Brexit.

What is surprising is that it would now appear to be dragging the great British institution of Wimbledon down to its level.

Mandrake disclosed last week that the Mail had spiked a feature it had commissioned about how Wimbledon had colluded with the Nazis in banning the German tennis ace Baron Gottfried von Cramm from playing in the last tournament before the Second World War.

The reason was the paper’s executives had belatedly twigged that Harold, the first Viscount Rothermere – then the Mail’s proprietor – had used his influence at Wimbledon to ensure von Cramm was not permitted to compete, even though he had been expected to win. Rothermere – a staunch supporter of Hitler – despised von Cramm as he had seen fit to criticise his idol.

After some goading, Wimbledon issued a statement in response to my piece in which they maintained that von Cramm had not been entered that year by the German Lawn Tennis Federation.

They also stated that the country had entered another player, Daniel Prenn.

I contacted Patrick Ryecart, the actor who has written the screenplay to a forthcoming film about von Cramm called Poster Boy – he had developed it in collaboration with the late Sir David Frost – and asked him to comment on Wimbledon’s statement.

He laughed. “Wimbledon have refused to make public the paperwork they have relating to this period, but this beggars belief,” he said.

"Just for a start, Prenn was banned from playing in Germany because he was a Jew and had actually escaped to the UK in 1935 and lived with the Sieff family, who founded Marks & Spencer.”

Wimbledon’s version of events is also contradicted by John Olliff, the revered player and former Daily Telegraph tennis correspondent, who wrote in his authoritative book, The Romance of Wimbledon, that von Cramm had been “refused” entry to the 1939 Wimbledon tournament.

I asked Alexandra Willis, Wimbledon’s spokeswoman, if she would now like me to run a line in this column stating unambiguously that nobody involved with Wimbledon at the time – including Rothermere – had sought to ban von Cramm from taking part in the 1939 tournament. She chose not to take me up on my offer.

(8) Private Eye: 1472 (15th June, 2018)

It's not often that outgoing Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre and Mail on Sunday editor Geordie Greig find common ground, but the Eye has unearthed an unusual case of cross-paper accord.

A few months back, the Mandrake column in the New European reported that the Daily Mail had spiked a piece on 1930s tennis champion Baron Gottfried von Cramm, who was opposed to the Nazi regime and imprisoned by the German authorities for having a homosexual affair. The piece was kyboshed after a staffer noticed a few lines detailing how Wimbledon's All England Club had banned the player from its 1939 tournament and discovered that the Mail's then owner, Harold, the first Viscount Rothermere, had used his influence to push for von Cramm's ban.

After the Daily Mail's rejection, the tennis piece was peddled elsewhere and picked up by the Mail on Sunday which, as Private Eye readers will know, is not at all averse to running stories deemed unacceptable by its Mail stablemate. An MoS news reporter was put on the case to forensically examine the details of why von Cramm was excluded from Wimbledon. At this point the hack unearthed an unexpected connection. The chairman of the All England Club at the time of von Cramm's exclusion was Sir Louis Greig, a member of Oswald Mosley's January club and the grandfather of one Geordie Greig. The piece was hastily spiked by the Mail on Sunday too. Game, set and match to the forefathers

References

(1) Deane MeGowen, New York Times (10th November, 1976)

(2) Elizabeth Wilson, Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon (2015) page 102

(3) Will Magee, Life, Death, Tennis and the Nazis: Gottfried von Cramm, The Man That Wimbledon Forgot (30th June, 2016)

(4) Raghu Krishnan, Times of India (13th June, 2011)

(5) Taki Theodoracopulos, The Spectator (2nd September, 2009)

(6) Charles Graves, The Bystander (8th July, 1936)

(7) Deane MeGowen, New York Times (10th November, 1976)

(8) Will Magee, Life, Death, Tennis and the Nazis: Gottfried von Cramm, The Man That Wimbledon Forgot (30th June, 2016)

(9) William Joseph Baker, Sports in the Western World (1988) page 257

(10) Robert S. Wistich, Who's Who in Nazi Germany (2001) page 33

(11) The Leeds Mercury (8th March 1938)

(12) The Daily Herald (4th May, 1938)

(13) Marshall Jon Fisher, A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War, and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever (2010) page 233

(14) Open letter sent to Adolf Hitler and signed by 26 leading sportsmen (May, 1938)

(15) Marshall Jon Fisher, A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War, and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever (2010) page 238

(16) Taki Theodoracopulos, The Spectator (2nd September, 2009)

(17) Elizabeth Wilson, Love Game: A History of Tennis, from Victorian Pastime to Global Phenomenon (2015) page 110

(18) Mandrake, The New European (13th April, 2018)

(19) Private Eye: 1472 (15th June, 2018) page 9

(20) Will Magee, Life, Death, Tennis and the Nazis: Gottfried von Cramm, The Man That Wimbledon Forgot (30th June, 2016)

(21) Richard K. Mastain, The Old Lady of Vine Street (2009) page 2

(22) Deane MeGowen, New York Times (10th November, 1976)

(23) The Daily Mirror (9th November, 1955)

(24) Marshall Jon Fisher, A Terrible Splendor: Three Extraordinary Men, a World Poised for War, and the Greatest Tennis Match Ever (2010) page 247