Winston Churchill: 1906-1916

Arthur Balfour resigned on 4th December 1905. Henry Campbell-Bannerman became the next prime minister. He immediate called for the dissolution of Parliament. The 1906 General Election took place the following month. The Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). The Labour Party, led by Keir Hardie did well, increasing their seats from 2 to 29. In the landslide victory Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (1)

Campbell-Bannerman appointed H. H. Asquith as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Other important appointments included Edward Grey (Foreign Secretary), David Lloyd George (Board of Trade), Richard Haldane (Secretary of State for War) and John Burns (President of the Local Government Board). Campbell-Bannerman announced that: "Our purpose is to substitute morality for egoism, honesty for honour, principles for usages, duties for properties, the empire of reason for the tyranny of fashion; dignity for insolence, nobleness for vanity, love of glory for the love of lucre... powerful and happy people for an amiable, frivolous and wretched people: that is to say every virtue of a Republic that will replace the vices and absurdities of a Monarchy." (2)

Winston Churchill won North West Manchester and Campbell-Bannerman appointed him as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. He selected Edward Marsh as his Private Secretary, "an aesthete involved in many aspects of the arts world and also at the centre of the homosexual circle in Edwardian society." Almost immediately they became devoted to each other and Marsh held the post for the next 23 years. Churchill wrote that "Few people have been so lucky as me to find in the dull and grimy recesses of the Colonial Office a friend whom I shall cherish and hold to all my life." (3)

Soon afterwards Churchill issued a memorandum on the future status of South Africa. He also had to face questions on what became known as "chinese slavery". In opposition the Liberals had condemned the importation of Chinese labourers into the Transvaal as being a return to slavery. However, Churchill was now forced to admit that in his opinion, the terms upon which the Chinese were employed could not be described as "slavery" without "some risk of terminological inexactitude". (4)

Frederick Smith, the recently elected Conservative MP for Liverpool Walton, attack on Churchill became one of the most famous maiden speeches in Parliamentary history, made reference to the wording of the Government's motion that the election result gave "unqualified" approval to Liberal policies. Smith argued that to "call a man an "unqualified slave", was to say that he could "be honestly described as completely servile, and not, merely, as semi-servile", but to call a man "an unqualified medical practitioner, or an unqualified Under-Secretary" was, he sneered, to say that "he is not entitled to any particular respect, because he has not passed through the normal period of training or preparation." (5)

Churchill caused considerable controversy when he made an attack on Lord Alfred Milner, the British High Commissioner at the time of the Boer War, who was deeply respected by the Conservative Party. In a debate on 21st March, 1906, he spoke of Milner with a patronising condescension which sounded both "impertinent" and "pompous", referring to him as a "retired Civil Servant without any pension or gratuity" and a man who "has ceased to be a factor in public life". (6)

Such language used by a junior minister in his early thirties about an imperial statesman was not appreciated by the House of Commons. Tory MPs renewed their criticisms of Churchill. One remarked that even Judas, had, after all, had the decency to hang himself afterwards. Churchill's advocacy of greater self-government for South Africa made him appear to be liberal in his attitude to the British Empire, but he remained a staunch imperialist. "There is no question for him but that the British Empire was a great engine of civilisation and an instrument for good. What he condemned were imperial actions which fell below what he regarded was the level of behaviour appropriate to those who bore the white man's burden." (7)

In September 1907 Churchill was given permission by the prime minister to go on a tour of Africa. He travelled by special train through Kenya (stopping on many occasions to "hunt" local wildlife). He also visited Uganda and Egypt. Questions were asked when it became public that he wrote tourist accounts for Strand Magazine. After allowing for expenses, Churchill made a profit of about £1,200 from his tour on Colonial Office business. (8)

In his book My African Journey (1908) he argued that the world was divided into races of very different aptitudes - the Europeans at the top, followed by Arabs and Indians and then at the bottom of the pile the Africans. "Armed with a superior religion and strengthened with Arab blood, they maintain themselves without difficulty at a far higher level than the pagan aboriginals among whom they live... I reflected upon the interval that separates these two races from each other, and on the centuries of struggle that the advance had cost, and I wondered whether the interval was wider and deeper than that which divides the modern European from them both." (9)

Winston Churchill irritated his boss, Victor Alexander Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, with his habit of minuting his views in strong words on papers which would be read by subordinates. He also upset Sir Francis John Hopwood, the Permanent Under-Secretary of the Colonial Office. "He (Churchill) is most tiresome to deal with and will, I fear, give trouble... The restless energy, uncontrollable desire for notoriety and the lack of moral perception make him an anxiety indeed!" (10)

It was suggested that Churchill deserved promotion to the Board of Education. This idea was rejected by Henry Campbell-Bannerman who pointed out that Churchill was a "very recent convert, hardly justifying cabinet rise." (11) Campbell-Bannerman told another government minister, Augustine Birrell: "Winston's promotion would be what the public might expect, and what the Press is already booming; he has done brilliantly where he is, and is full of go and ebullient ambition. But he is only a Liberal of yesterday, his tomorrow being a little doubtful... Also, wholly ignorant of and indifferent to the subject." (12)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman suffered a severe stroke in November, 1907. He returned to work following two months rest but it soon became clear that the 71 year-old prime minister was unable to continue. On 27th March, 1908, he asked to see Asquith. According to Margot Asquith: "Henry came into my room at 7.30 p.m. and told me that Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had sent for him that day to tell him that he was dying... He began by telling him the text he had chosen out of the Psalms to put on his grave, and the manner of his funeral... Henry was deeply moved when he went on to tell me that Campbell-Bannerman had thanked him for being a wonderful colleague." (13)

Campbell-Bannerman suggested to Edward VII that Herbert Asquith should replace him as Prime Minister. However, the King with characteristic selfishness was reluctant to break his holiday in Biarritz and ordered him to continue. On 1st April, the dying Campbell-Bannerman, sent a letter to the King seeking his permission to give up office. He agreed as long as Asquith was willing to travel to France to "kiss hands". (14)

Asquith decided to promote Churchill to the cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Aged 33, he was the youngest Cabinet member since 1866. However, at that time it was necessary for new Ministers had to submit themselves for re-election. Churchill had upset too many people over the last two years and he lost North West Manchester to William Joynson-Hicks, the Conservative Party candidate, by 429 votes. Asquith now had to force Edmund Robertson, the MP for Dundee, to go to the House of Lords, and he was elected to this seat in May, 1908, with a comfortable majority. (15)

Paul Addison has described Churchill as "a great admirer of beautiful women, but self-centred and gauche in their company, Churchill had already proposed to Pamela Plowden and Ethel Barrymore, only to be rejected by both". He met Clementine Hozier at a dinner party in 1908. "Clementine was twenty-three; her background was relatively impoverished and a little bit rackety - in the sense that her mother, Lady Blanche Hozier, had enjoyed so many extra-marital amours that Clementine was not entirely sure as to the identity of her father." (16)

Clementine held strong hostile views against the Tories. Churchill attempted to convince her that he shared her views: "The Conservative Party is filled with old doddering peers, cute financial magnates, clever wirepullers, big brewers with bulbous noses. All the enemies of progress are there - weaklings, sleek, slug, comfortable, self-important individuals." (17)

In August he proposed marriage and it was accepted. Violet Asquith, the daughter of Herbert Henry Asquith, the prime minister, wrote in her diary when she heard the news: "I must say I am much gladder for her sake than I am sorry for his. His wife could never be more to him than an ornamental sideboard as I have often said and she is unexacting enough not to mind not being more. Whether he will ultimately mind her being as stupid as an owl I don't know - it is a danger no doubt - but for the moment at least she will have a rest from making her own clothes and I think he must be a little in love. Father thinks that it spells disaster for them both." (18)

Winston and Clementine were married at St Margaret's, Westminster, on 12th September 1908. "Churchill expected his wife to be a loyal follower, and it was a role she was content to play. The unhappy child of a disastrous marriage and a financially precarious home, Clementine found in Winston a faithful husband who loved her, sustained her in material comfort, and placed her in the front row of a great historical drama." (19)

Winston Churchill admitted to Asquith when he was appointed as President of the Board of Trade that he was "ignorant of social issues". This was a problem as the Board of Trade was one of the key ministries in the social field. During his political career he had never questioned the immense inequalities in British society, where about a third of the population lived in poverty "where a third of the national income went to just three per cent of the population; half of the nation's capital belonged to one-seventieth of the population; the average national wage was 29s a week and most people were unable to make provision for old age, sickness and unemployment." (20)

Churchill had a strictly limited view of the scope. Throughout his political life the major theme of his thinking was a concern about the stability of society and preservation of the existing order. However, he was aware that change was necessary in order to achieve "national efficiency". He had regular meetings with Beatrice Webb and explored her views on the subject. She wrote that Churchill was "very anxious to be friends and asked to be allowed to come and discuss the long-term question". (21) According to Webb on another occasion he "made me sit next to him and was most obsequious - eager to assure me that he was willing to absorb all the plans we could give him." (22)

John Charmley has commented that: "Churchill may not have had any great insight into how to deal with the social problems of the masses, but he knew a lady who did. If Mrs Webb was anxious to be part of a secular priesthood, 'disinterested experts' devising 'a blueprint for society', then Churchill was eager to grant her wish." (23) In an article published in The Nation he advocated Webbian solutions to the social problems of the time. (24)

Churchill, like most politicians, was deeply worried about how Britain's share of world markets were passing to the United States and Germany. Churchill was greatly influenced by the reforms introduced by Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s. As The Contemporary Review reported: "English progressives have decided to take a leaf out of the book of Bismarck who dealt the heaviest blow against German socialism not by laws of oppression... but by the great system of state insurance which now safeguards the German workmen at almost every point of his industrial career." (25)

In the autumn of 1908 Churchill advocated the introduction of unemployment insurance. The scheme was restricted to trades which suffered from cyclical unemployment (shipbuilding, engineering and construction) and excluded those in decline, those with a large amount of casual labour and those with substantial short-time working (such as mining and cotton spinning). It would cover only about two million workers. The plan was that employees would contribute twice as much per week as the State and employers. The benefit would only be paid for a maximum of fifteen weeks and at a low enough rate to "imply a sensible and even severe difference between being in work or out of work." (26)

In April 1909, Churchill presented the draft Bill to the Cabinet. Employer and State contributions had increased but benefits had decreased and were to be calculated on a stiff sliding-scale over the fifteen weeks so that so that, as Churchill told fellow ministers, "an increasing pressure is put on the recipient of benefit to find work". The Cabinet was divided over the issue. Some like David Lloyd George wanted a more generous and more wide-ranging scheme. Lloyd George took over responsibility of the introduction of a national insurance scheme but the paying of unemployment benefits did not take place until four years later. (27)

Churchill's first task was taking the Trade Board Bill through the House of Commons. The measure organised employers to create a minimum wage in certain trades with the history of low wages, because of surplus of available workers, the presence of women workers, or the lack of skills. It was designed to cover only 200,000 workers in just four carefully defined trades, chain-making, ready-made tailoring, paper-box making, and the machine-made lace and finishing trade. (28)

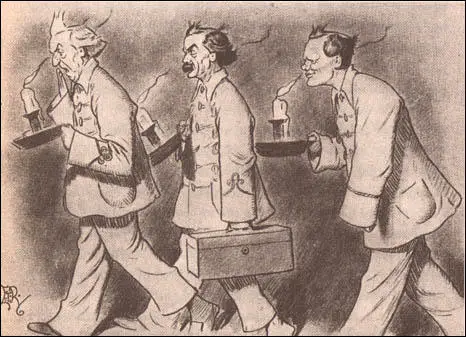

Winston Churchill in their pyjamas working late at night in their attempt

to pass radical legislation to improve the life of the poor. (25th August 1909)

Winston Churchill argued: "It is a serious national evil that any class of His Majesty's subjects should receive less than a living wage in return for their utmost exertions. It was formerly supposed that the working of the laws of supply and demand would naturally regulate or eliminate that evil. The first clear division which we make on the question to-day is between healthy and unhealthy conditions of bargaining. That is the first broad division which we make in the general statement that the laws of supply and demand will ultimately produce a fair price. Where in the great staple trades in the country you have a powerful organisation on both sides, where you have responsible leaders able to bind their constituents to their decision, where that organisation is conjoint with an automatic scale of wages or arrangements for avoiding a deadlock by means of arbitration, there you have a healthy bargaining which increases the competitive power of the industry, enforces a progressive standard of life and the productive scale, and continually weaves capital and labour more closely together. But where you have what we call sweated trades, you have no organisation, no parity of bargaining, the good employer is undercut by the bad, and the bad employer is undercut by the worst; the worker, whose whole livelihood depends upon the industry, is undersold by the worker who only takes the trade up as a second string, his feebleness and ignorance generally renders the worker an easy prey to the tyranny." Churchill made it clear that such State interference was only justified in exceptional circumstances and should not be extended to industry as a whole". (29)

In the midst of the worst recession since 1879, the Government was under increasing pressure to take some action to deal with unemployment and the labour market. William Beveridge proposed a national scheme of labour exchanges. It was based on the system used in Germany whose 4,000 exchanges that filled over one million jobs a year. Churchill shared Beveridge's passion for efficiency and a hatred of waste and his views on the working class. Beveridge told his brother-in-law, R. H. Tawney: "The well-to-do represent on the whole a higher level of character and ability than the working class because in the course of time the better stocks have come to the top. A good stock is not permanently kept down: it forces its way up in the course of generations of social change, and so the upper classes are on the whole the better classes." (30)

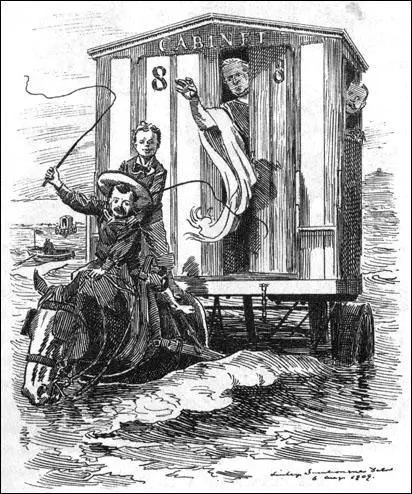

H. H. Asquith: "Steady on, you young terrors, you're making it very

uncomfortable for us in here."

Linley Sambourne, Getting Into Deep Water (11th November, 1909)

Winston Churchill told the Cabinet that labour exchanges would not in themselves create more jobs. The exchanges were viewed as a way of improving the efficiency of the industrial system, providing "intelligence" about the state of industry and saving economic waste through the more efficient use of labour. It was also hoped that exchanges would have a social and moral function since they would, as Churchill predicted "enable the idle vagrant to be discovered unmistakably and sent to an institution for disciplinary detention." (31)

The proposal for creating labour exchanges was announced on 17th February 1909. There would be a network of several hundred exchanges as part of a national reporting system on the labour market. The trade union movement initially opposed the scheme as they feared that labour exchanges would be used to break strikes. The only concession he made to the unions was that a man would not to be penalised for refusing to accept a job at less than union rates. He told the Engineering Employers Association: "If anybody had said a year ago that the trades unions would have agreed to a government labour exchange sending 500 or 1,000 men to an employer whose men are out on strike... nobody would have believed it all." (32)

Churchill's proposals were so lacking in radicalism that they were fully supported by the Conservative Party. However, to those who wish to see Churchill as a friend of the poor, this measure was very important in helping the working-class find work. Geoffrey Best, the author of Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001), claimed that even though Churchill's reforms "were small and limited measures in themselves, mere particles in the radiant beams of his grand vision of Britain... they were none the less pioneering pieces of the structure which, forty years later, would become the British welfare state." (33)

Roy Jenkins took a different view: "Churchill's approach although liberal, was highly patrician. There was never any attempt to pretend that his own often urgent need for large sums of money in order to sustain his extravagences bore any relation to the problems of the deserving poor. He did not pretend to understand these from the inside, merely to sympathize with them on high. He was of a different order, almost of a different race." (34)

By February 1910, 61 exchanges were open and a year later the total had risen to 175. Nearly all of them were situated in converted buildings in the worst parts of towns in order to save money. In the first year nearly one and a half million applications were registered, but jobs were found for only a quarter of the applicants. "They never took over any other function than providing a place where a limited number of jobs were advertised; they did not help to organise the labour market and there is no evidence that they helped to create employment. They were strongly disliked by the trade unions, who suspected them of undercutting union rates and providing blackleg labour." (35)

In 1909 David Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. (36)

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theoretical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." MacDonald went on to argue that the House of Lords should not attempt to block this measure. "The aristocracy... do not command the moral respect which tones down class hatreds, nor the intellectual respect which preserves a sense of equality under a regime of considerable social differences." (37)

David Lloyd George admitted that he would never have got his proposals through the Cabinet without the strong support of Herbert Asquith and Winston Churchill. He spoke at a large number of public meetings of the pressure group he formed, the Budget League. Churchill rarely missed a debate on the issue and one newspaper report suggested that he had attended one late night debate in the House of Commons in his pajamas. Lloyd George told a close friend: "I should say that I have Winston Churchill with me in the Cabinet, and above all the Prime Minister has backed me up through thick and thin with splendid loyalty." (38)

Churchill launched a bitter attack on the House of Lords: " When I began my campaign in Lancashire I challenged any Conservative speaker to come down and say why the House of Lords... should have the right to rule over us, and why the children of that House of Lords should have the right to rule over our children. My challenge has been taken up with great courage by Lord Curzon. No, the House of Lords could not have found any more able and, I will add, any more arrogant defender... His claim resolves itself into this, that we should maintain in our country a superior class, with law-giving functions inherent in their blood, transmissible by them to their remotest posterity, and that these functions should be exercised irrespective of the character, the intelligence or the experience of the tenant for the time being and utterly independent of the public need and the public will. Now I come to the third great argument of Lord Curzon... 'All civilization has been the work of aristocracies.' Why, it would be much more true to say the upkeep of the aristocracy has been the hard work of all civilizations." (39)

Despite the passionate speeches of Churchill and Lloyd George it was clear that the House of Lords would block the budget. Herbert Asquith asked the King to create a large number of Peers that would give the Liberals a majority. Edward VII refused and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, wrote to Asquith that "to create 570 new Peers, which I am told would be the number required... would practically be almost an impossibility, and if asked for would place the King in an awkward position". (40)

On 30th November, 1909, the Peers rejected the Finance Bill by 350 votes to 75. Asquith had no option but to call a general election. During the campaign Churchill led the Liberal onslaught against the House of Lords. He argued that "the time has come for the total abolition of the House of Lords" and described the former Foreign Secretary, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, as "the representative of a played out, obsolete, anachronistic Assembly, a survival of a feudal arrangement utterly passed out of its original meaning, a force long since passed away, which only now requires a smashing blow from the electors to finish it off for ever." (41)

In January, 1910 General Election, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. John Grigg, the author of The People's Champion (1978) argues that the reason why the "people failed to give a sweeping, massive endorsement to the People's Budget" was that the electorate in 1910 was "by no means representative of the whole British nation". He points out that "only 58 per cent of adult males had the vote, and it is a fair assumption that the remaining 42 per cent would, if enfranchised, have voted in very large numbers for Liberal or Labour candidates. In what was still a disproportionately middle-class electorate the fear of Socialism was strong, and many voters were susceptible to the argument that the Budget was a first installment of Socialism." (42)

Home Secretary

On the day the election results were announced Winston Churchill accepted the post of Home Secretary, with the responsibility for the police, prisons, and prisoners. Only Robert Peel, the founder of the police force, had held the office at an earlier age, thirty-three. The prospects of the new office filled him "with excitement and exhilaration". From his first days as Home Secretary he embarked upon a comprehensive programme of prison reform. This included reducing the time someone could spend in solitary confinement. (43)

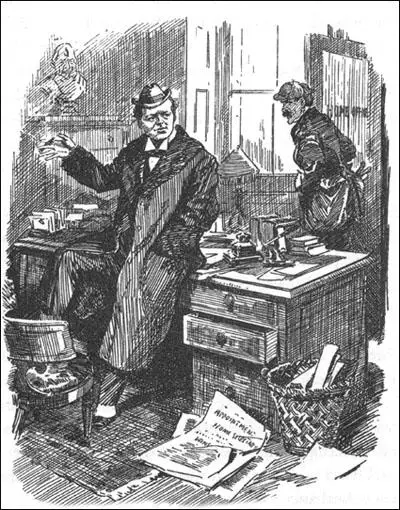

Winston Churchill: "Yes; but I shan't forget you. If you find yourself in trouble

I'll see if I can't get you a reprieve, for the sake of old times!

Leonard Raven-Hill, When constabulary duty's to be done (23rd February, 1910)

In March 1910, he created a distinction between criminal and political prisoners. "I have given my best consideration to this subject with reference not solely to the treatment of women suffragist prisoners, but generally to the regulations which govern the treatment of political prisoners. I do not feel that any differences of prison treatment should be based upon a consideration of the motives which actuated the offender. Motives are for the Courts to appraise, and it must be presumed that all due consideration has been given to them in any sentence which is imposed... I feel, as did my predecessor, that prison rules which are suitable to criminals guilty of dishonesty or cruelty, or other crimes implying moral turpitude, should not be applied inflexibly to those whose general character is good and whose offences, however reprehensible, do not involve personal dishonour." (44)

Churchill upset the trade union movement during the Newport Docks strike in May 1910. With the dockers on strike, the owners wanted to bring in outside labour to break the strike and the local magistrates, alarmed at the possibility of mass disorder, asked the Home Office to provide troops or police to protect the blacklegs. Churchill was on holiday and Richard Haldane, who was in charge at the time, refused. Churchill quickly returned to London and authorised the use of 250 Metropolitan police, with 300 troops in reserve, to support the owners and protect the outside labour they brought in. (45)

Six months later Churchill was faced with another dispute in South Wales, this time in the Rhondda valley where a lock-out and strike following a conflict over pay rates for a difficult new seam led to a bitter ten-month strike. Once again Churchill was asked to send troops after strikers rioted. At first Churchill called for arbitration. The following day he was attacked by Conservative newspapers, particularly by The Times, that declared that if "loss of life" occured as a result of the riots, "the responsibility will lie with the Home Secretary." (46)

On 8th November, 1910, Churchill sent in the cavalry and went on patrol in Tonypandy and the neighbouring valleys. He also deployed 900 Metropolitan police and 1,500 officers from other forces to support two squadrons of hussars and two infantry companies stationed in the area. James Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, protested against the "impropriety" of sending in troops and the "harsh methods" being used. Churchill told King George V that the "owners are very unreasonable" and "both sides are fighting one another regardless of human interests or the public welfare." However, the troops, remained in the area for eleven months, supporting the police, and were at times deplyed on the streets with fixed bayonets. (47)

The following month Churchill was once again in the headlines. Max Smoller, and Fritz Svaars rented a house, 11 Exchange Buildings in Houndsditch. Svaars told the landlord that he wanted it for two or three weeks to store Christmas goods. According to one newspaper account: "This particular house in Exchange Buildings was rented and there went to live there two men and a woman. They were little known by neighbours, and kept very quiet, as if, indeed, to escape observation. They are said to have been foreigners in appearance, and the whole neighbourhood of Houndsditch containing a great number of aliens, and removal being not infrequent, the arrival of this new household created no comment." (48)

On 16th December 1910, a gang that is believed to included Smoller, Svaars, Peter Piaktow (Peter the Painter), Max Smoller, Fritz Svaars, George Gardstein, Yakov Peters, Yourka Dubof, Karl Hoffman, John Rosen and William Sokolow, attempted to break into the rear of Henry Harris's jeweller's shop from Exchange Buildings. A neighbouring shopkeeper, Max Weil, heard their hammering, informed the City of London Police, and nine unarmed officers arrived at the house. Sergeant Robert Bentley knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings. The door was open by Gardstein and Bentley asked him: "Have you been working or knocking about inside?" Bentley did not answer him and withdrew inside the room. Bentley gently pushed open the door, and was followed by Sergeant Bryant. Constable Arthur Strongman was waiting outside. "The door was opened by some person whom I did not see. Police Sergeant Bentley appeared to have a conversation with the person, and the door was then partly closed, shortly afterwards Bentley pushed the door open and entered." (49)

According to Donald Rumbelow, the author of The Siege of Sidney Street (1973): "Bentley stepped further into the room. As he did so the back door was flung open and a man, mistakenly identified as Gardstein, walked rapidly into the room. He was holding a pistol which he fired as he advanced with the barrel pointing towards the unarmed Bentley. As he opened fire so did the man on the stairs. The shot fired from the stairs went through the rim of Bentley's helmet, across his face and out through the shutter behind him... His first shot hit Bentley in the shoulder and the second went through his neck almost severing his spinal cord. Bentley staggered back against the half-open door and collapsed backwards over the doorstep so that he was lying half in and half out of the house." (50)

Sergeant Robert Bentley was very badly injured. The burglars also opened fire on the other policemen. Two bullets hit Sergeant Charles Tucker, who was killed outright. Constable Arthur Strongman, not knowing the sergeant was dead, carried him to safety, followed by one of the gunmen, who kept firing, but missed. Constable Walter Choate saw a gunman running through the shadows. "With almost suicidal courage, he grabbed him and refused to let go even as bullets hit him. His action probably saved PC Strongman's life, because two other burglars now ran to their captured confederate's assistance, firing at PC Choate, until he finally let go." Within 24 hours, the death toll had risen to three, when Bentley and Choate died in hospital. (51)

The men escaped but on 1st January, 1911, the police was told that they would find the men in the lodgings rented by a Betsy Gershon at 100 Sidney Street. It seems that one of the gang, William Sokolow, was Betsy's boyfriend. This was part of a block of 10 houses just off Commercial Road. The tenant was a ladies tailor, Samuel Fleischmann. With his wife and children he occupied part of the house and sublet the rest. Other residents included an elderly couple and another tailor and his large family. Betsy had a room at the front of the second floor. Superintendent Mulvaney was put in charge of the operation. At midday on 2nd January, two large horse-drawn vehicles concealing armed policeman were driven into the street and the house placed under observation. By the afternoon over 200 officers were on the scene, with armed men stationed in shop doorways facing the house. Meanwhile, plain-clothed policemen began to evacuate the residents of 100 Sidney Street. (52)

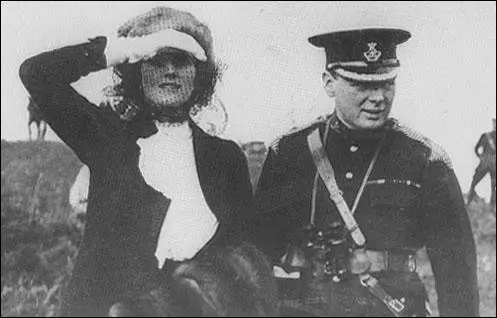

Winston Churchill and his private secretary, Edward Marsh, decided to go to Sidney Street. One of Churchill's biographers, Roy Jenkins, pointed out that Churchill "could not resist going to see the fun himself... both of them top-hatted and Churchill made more conspicuous by a fine astrakhan-collared overcoat, they provided a wonderful photographic opportunity, which was duly exploited." (53)

Clive Ponting has also been very critical of Churchill's actions. commented: "He arrived just before midday and characteristically took charge of the operation - calling up artillery to demolish the house and personally checking on possible means of escape. When the house caught fire he ordered, probably with police consent, the fire brigade not to attempt to put it out. When the fire burnt itself out, two bodies were found and Churchill left the scene just before 3pm. His presence had been unnecessary and uncalled for - the senior Army and police officers present could easily have coped with the situation on their own authority. But Churchill with his thirst for action and drama could not resist the temptation." (54)

Martin Gilbert took a very different view and believed that the Conservative Party saw this as an opportunity to unfairly attack Churchill. Arthur Balfour remarked in the House of Commons: "He (Churchill) was, I understand, in a military phrase, in what was known as the zone of fire - he and a photographer were both risking valuable lives. I understand what the photographer was doing, but what was the right honourable gentleman doing?" The Palace Theatre in London showed film of the Siege of Sidney Street but the audience booed Churchill and shouted out "shoot him". Edward Marsh remarked, "Why are the London music-hall audiences so bigoted and uniformly Tory?" (55) Churchill blamed the Pro-Tory press and in a letter published in The Times he protested at the "sensational accounts" of the siege that had appeared in the newspapers and at "the spiteful comments based upon them". (56)

That summer Winston Churchill once again became involved in another industrial dispute. He became convinced that German money was funding a dock and rail strike over union recognition in Liverpool and on the 14th August 1911 he sent in the army who opened fire on strikers. It is estimated that about 50,000 soldiers arrived in the city. "His attitude was openly partisan; in every case of a protest about police or military violence he simply accepted the official account and dismissed the version from the strikers." David Lloyd George intervened and persuaded the employers to settle the dispute. When he heard the news he immediately telephoned Lloyd George to complain as he wanted an open conflict followed by a clear defeat for the unions. (57)

Winston Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (58)

Under pressure from the Women's Social and Political Union, in 1911 the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. According to Lucy Masterman, it was her husband, Charles Masterman, who provided the arguments against the legislation: "He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to and began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that 'fallen women' would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself...He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food." (59)

Churchill argued in the House of Commons: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife.... What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters? (60)

First Lord of the Admiralty

Winston Churchill was extremely proud of the British Empire but he was very concerned about its future. Superficially the empire seemed the strongest power in the world. However, he was aware that it was in trouble. This vast, sprawling Empire was not integrated politically, economically or strategically and was a drain on Britain's very limited resources. An island of some forty million people with an economy that was being rapidly overtaken by other powers such as the United States and Germany. It has been argued that during this period "Churchill came up against the fundamental factor that was to shape all his political life - Britain's position as a great power was declining." (61)

Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, became involved in an arms race with German Navy. In 1909 authorized an additional four dreadnoughts, hoping that Germany would be willing to negotiate a treaty about battleship numbers. If this did not happen, an additional four ships would be built. In 1910, the British eight-ship construction plan went ahead, including four Orion-class super-dreadnoughts. Germany responded by building three warships, giving the United Kingdom a superiority of 22 ships to 13. Negotiations began between the two countries but talks foundered on the question on whether British Commonwealth battlecruisers should be included in the count. (62)

David Lloyd George complained bitterly to H. H. Asquith about the demands being made by Reginald McKenna to spend more money on the navy. He reminded Asquith of "the emphatic pledges given by us before and during the general election campaign to reduce the gigantic expenditure on armaments built up by our predecessors... but if Tory extravagance on armaments is seen to be exceeded, Liberals... will hardly think it worth their while to make any effort to keep in office a Liberal ministry... the Admiralty's proposals were a poor compromise between two scares - fear of the German navy abroad and fear of the Radical majority at home... You alone can save us from the prospect of squalid and sterile destruction." (63)

Lloyd George was constantly in conflict with McKenna and suggested that Winston Churchill, should become First Lord of the Admiralty. H. H. Asquith took this advice and Churchill was appointed to the post on 24th October, 1911. McKenna, with the greatest reluctance, replaced him at the Home Office. He was now in charge of the greatest naval establishment in the world, "with its fleet patrolling the seven seas, and its training schools and dockyards and warehouses and harbours forming a service that embodied British might." (64)

Churchill was very excited by this new post. He had told his wife two years earlier that he should be in charge of the armed forces: "These military men very often fail altogether to see the simple truths underlying the relationships of all armed forces, & how the levers of power can be used upon them. Do you know I would greatly like to have some practice in the handling of large forces. I have much confidence in my judgment on things, when I see clearly, but on nothing do I seem to feel the truth more than in tactical combinations. It is a vain and foolish thing to say - but you will not laugh at it. I am sure I have the root of the matter in me - but never I fear in this state of existence will it have a chance of flowering - in bright red blossom." (65)

Churchill's appointment worried the press: "The Conservative journals, invariably pro-Navy had little faith in Churchill's appointment, fearful that his rhetorical style and changeable moods, as they saw it, were unsuitable to that pre-eminent administrative post." (66) Some of Britain's newspapers questioned his appointment. For example, the Sunday Observer commented: "We cannot detect in his career any principles or even any consistent outlook upon public affairs. His ear is always on the ground; he is the true demagogue, sworn to give the people what they want, or rather, and that is infinitely worse, what he fancies they want. No doubt he will give the people an adequate Navy if they insist upon it." (67)

Churchill also concerned himself with land forces. On 13th August, 1911, he sent a memorandum to the Committee of Imperial Defence. He warned that in event of a war France would have great difficulty holding a German attack. Churchill " outlined the measures Britain should take, including 107,000 men to be sent to France on the outbreak of war and 100,000 troops of the British Army in India who should be moved at once out of India, enabling them to reach Marseilles by the fortieth day." It would be vital that during the progress of the war that the size of the British Army should be increased so as "to secure or re-establish British interests outside Europe, even if, through the defeat or desertion of the allies, we were forced to continue the war alone." (68)

The Spectator claimed that Churchill "has not the loyalty, the dignity, the steadfastness to make an efficient head of a great office." However, he gained the support of the Conservative press when he made a speech on 9th November, 1911, making it clear that Britain would retain her existing margin of superiority over the German Navy even if the Germans stepped up their rate of building. This brought him plaudits from old enemies like Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, whose newspapers, The Daily Mail, The Times, The Daily Mirror and The Evening News, had constantly attacked the Liberal government, told Churchill: "I judge public men on their public face and I believe that your inquiring, industrious mind is alive to the national danger." (69) Churchill's speech upset radicals such as Wilfred Scawen Blunt who sorrowfully concluded that he was "bitten with Grey's anti-German policy." (70)

One of Churchill's first decisions was to set up the Royal Naval Air Service. He also established an Air Department at the Admiralty so as to make full use of this new technology. Churchill was so enthusiastic about these new developments that he took flying lessons. The Army envisaged its air service as primarily one of reconnaissance, avoiding, wherever possible, any actual air battles. "Churchill wanted the Navy to use aircraft more aggressively; both bomb-dropping and machine-gunnery became part of the experimentation and training of the Royal Naval Air Service." (71)

On 7th February, 1912, Churchill made a speech where he pledged naval supremacy over Germany "whatever the cost". Churchill, who had opposed naval estimates of £35 million in 1908, now proposed to increase them to over £45 million. The German Naval Attaché, Captain Wilhelm Widenmann, wrote to Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, in an attempt to explain this change in policy. He claimed that Churchill was "clever enough" to realise that the British public would support "naval supremacy" whoever was in charge "as his boundless ambition takes account of popularity, he will manage his naval policy so as not to damage that" even dropping "the ideas of economy" which he had previously preached. (72)

Leonard Raven-Hill, Dogg'd (29th May, 1912)

The Admiralty reported to the British government that by 1912 Germany would have seventeen dreadnoughts, three-fourths the number planned by Britain for that date. At a cabinet meeting David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill both expressed doubts about the veracity of the Admiralty intelligence. Churchill even accused Admiral John Fisher, who had provided this information, of applying pressure on naval attachés in Europe to provide any sort of data he needed. (73)

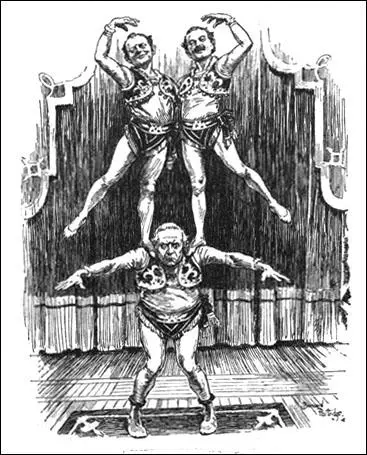

David Lloyd George: "Well, you can have it. Give me the land!"

Leonard Raven-Hill, The Taxable Element (7th August, 1912)

Admiral Fisher refused to be beaten and contacted King Edward VII about his fears. He in turn discussed the issue with H. H. Asquith. Lloyd George wrote to Churchill explaining how Asquith had now given approval to Fisher's proposals: "I feared all along this would happen. Fisher is a very clever person and when he found his programme in danger he wired Davidson (assistant private secretary to the King) for something more panicky - and of course he got it." (74)

Winston Churchill now advocated spending £51,550,000 on the Navy in 1914. The "new ruler of the King's navy demanded an expenditure on new battleships which made McKenna's claims seem modest". (75) Lloyd George remained opposed to what he saw as inflated naval estimates and was not "prepared to squander money on building gigantic flotillas to encounter mythical armadas". According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, recorded they were drifting wide apart on principles". (76) Riddell reported there were even rumours that Churchill was "mediating... going over to the other side." (77)

First World War

On 28th July, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The following day the Kaiser Wilhelm II promised Britain that he would not annex any French territory in Europe provided the country remained neutral. This offer was immediately rejected by Sir Edward Grey in the House of Commons. On 30th July, Grey wrote to on Theobold von Bethmann Hollweg: "His Majesty's Government cannot for one moment entertain the Chancellor's proposal that they should bind themselves to neutrality on such terms. What he asks us in effect is to engage and stand by while French colonies are taken and France is beaten, so long as Germany does not take French territory as distinct from the colonies. From the material point of view the proposal is unacceptable, for France, without further territory in Europe being taken from her, could be so crushed as to lose her position as a Great Power, and become subordinate to German policy. Altogether apart from that, it would be a disgrace to us to make this bargain with Germany at the expense of France, a disgrace from which the good name of this country would never recover. The Chancellor also in effect asks us to bargain away whatever obligation or interest we have as regards the neutrality of Belgium. We could not entertain that bargain either." (78)

C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, made it clear what he thought of the conflict. "Not only are we neutral now, but we could, and ought to remain neutral throughout the whole course of the war... We wish Serbia no ill; we are anxious for the peace of Europe. But Englishmen are not the guardians of Serbia well being, or even of the peace of Europe. Their first duty is to England and to the peace of England... We care as little for Belgrade as Belgrade does for Manchester." (79)

At a Cabinet meeting on Friday, 31st July, more than half the Cabinet, including David Lloyd George, Charles Trevelyan, John Burns, John Morley, John Simon and Charles Hobhouse, were bitterly opposed to Britain entering the war. Only two ministers, Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey, argued in favour and H. H. Asquith appeared to support them. At this point, Churchill suggested that it might be possible to continue if some senior members of the Conservative Party could be persuaded to form a Coalition government. (80)

Winston Churchill wrote to Lloyd George after the Cabinet meeting: "I am most profoundly anxious that our long co-operation may not be severed... I implore you to come and bring your mighty aid to the discharge of our duty. Afterwards, by participating, we can regulate the settlement." He warned that if Lloyd George did not change his mind: "All the rest of our lives we shall be opposed. I am deeply attached to you and have followed your instructions and guidance for nearly 10 years." (81)

On 1st August the Governor of the Bank of England, Sir Walter Cunliffe, visited Lloyd George to inform him that the City was totally against British intervening in the war. Lloyd George later recalled: "Money was a frightened and trembling thing. Money shivered at the prospect. Big Business everywhere wanted to keep out." Three days later The Daily News argued that it would help business if Britain kept out of the war, "if we remained neutral we should be able to trade with all the belligerents... We should be able to capture the bulk of their trade in neutral markets." (82)

Later that day Grey told the French Ambassador in London that the British government would not stand by and see the German Fleet attack the French Channel Ports. On 2nd August another Cabinet meeting took place. Marvin Rintala, the author of Lloyd George and Churchill: How Friendship Changed Politics (1995) points out: "A major change had clearly taken place within the cabinet. That change centred on Lloyd George. According to Asquith, on the morning of 2 August, Lloyd George was still against any kind of British intervention in any event ... Throughout that long Sunday he had contemplated retiring to North Wales if Britain went to war. It appears that until 3 August he intended to resign from the Cabinet upon any British declaration of war ... In fact, Lloyd George was first firmly against war, and then equally firmly for war." (83)

Lloyd George's change of mind shocked government ministers. John Burns immediately resigned as he now knew war was inevitable. Charles Trevelyan, John Morley and John Simon also handed in letters of resignation with "at least another half-dozen waited upon the effective hour". (84) According to the historian, A. J. P. Taylor: "At 10.30 p.m. on 4th August 1914 the king held a privy council at Buckingham Palace, which was attended only by one minister and two court officials. The council sanctioned the proclamation of a state of war with Germany from 11 p.m. That was all. The cabinet played no part once it had resolved to defend the neutrality of Belgium. It did not consider the ultimatum to Germany, which Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary, sent after consulting only the prime minister, Asquith, and perhaps not even him." (85)

Asquith supported the war but was deeply disturbed by the way some Cabinet ministers such as Winston Churchill responded: "Winston dashed into the room radiant, his face bright, his manner keen and told us - one word pouring out on the other - how he was going to send telegrams to the Mediterranean, the North Sea and God knows where! You could see he was a really happy man, I wondered if this was the state of mind to be in at the opening of such a fearful war as this." (86)

Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George's secretary and mistress, was also shocked by Churchill's reaction to the outbreak of war. She was with a group of friends when "upon this grave assembly burst Churchill, a cigar in his mouth, radiant, smiling with satisfaction. 'Well!' he exclaimed. 'The deed is done!' The dream of his life had come to pass. Little he recked of the terrors of war and the price that must be paid. His chance had come!" (87)

As one historian has pointed out: "Seldom has there been a statesman as good as glorifying war, and as indecently eager to wage war, as Winston Churchill. All his works demonstrate his love of war, glamorize its glories and minimize its horrors." (88) When it was suggested that David Lloyd George should acknowledging the cheering crowd that had assembled outside Parliament he commented: "This is not my crowd. I never want to be cheered by a war crowd." (88a)

In the early months of the First World War the German Army made significant gains in France and Belgium. Winston Churchill sent naval artillery and areoplanes from his Royal Naval Air Service. and established bases near Dunkirk. He also landed a brigade of Marines at Ostend. Under his instructions carried out Britain's first-ever military bombing operations (attacks on Zeppelins and their hangers). (89)

By 28th September, 1914, Antwerp was under siege. King Albert I and his Belgian government were based in the city. There was also 145,000 trained Belgian troops, within its fortified perimeter. On 1st October, H. H. Asquith wrote to Venetia Stanley about the situation in Antwerp that "its fall would be a great moral blow to the allies" but added "of course it would be idle butchery to send" British soldiers to defend the city. (90)

Churchill ignored Asquith's views and gained permission from Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, to go to organise the defence of Antwerp. He took with him 2,000 men of the Royal Marine Brigade to support those who were already in Antwerp. On 5th October he sent a message to Asquith, where he offered to resign his office and "undertake command of relieving and defensive forces assigned to Antwerp in conjunction with Belgian Army, provided that I am given necessary military rank and authority, and full powers of a commander of a detached force in the field. I feel it my duty to offer my services because I am sure this arrangement will afford the best prospects of a victorious result to an enterprise in which I am deeply involved." (91) The message has been described as "surely one of the most extraordinary communications ever made by a British Cabinet Minister to his leader". (92)

Lord Kitchener was prepared to agree to his request and make him a Lieutenant-General but Asquith over-ruled him and Churchill was ordered back to Britain. Ted Morgan, the author of Winston Churchill (1983) has argued that Churchill's decision to try and hold Antwerp was wrong: "Holding Antwerp was an article of faith for Churchill. Imbued as he was with a sense of historical precedent, he must have remembered that during the Napoleonic Wars, the British had landed on Walcheren Island, only thirty miles from Antwerp... Instead of defending Antwerp, a pocket cut off from the rest of the allied front, the Belgians should have seen themselves as part of an overall Continental strategy and pulled back their Army to fight jointly with the French." (93)

King Albert I and his Belgian government left Antwerp on 9th October and the city surrendered the next day. The price of Churchill's intervention was that the Royal Naval Division lost a total of 2,610 men, most of whom were either prisoners of war or interned in the neutral Netherlands. Reaction to Churchill's adventure was highly critical and badly damaged his reputation. Asquith wrote that he thought the use of the professional Royal Marine Brigade was justified but "nothing can excuse Winston (who knew all the facts) from sending in the other Naval Brigades." (94)

David Lloyd George agreed with Asquith and told his mistress, Frances Stevenson, that he was "rather disgusted" with Churchill who had "behaved in a rather swaggering way when over there, standing for photographers and cinematographers with shells bursting near him". (95) Admiral Herbert Richmond wrote in his diary that "it is a tragedy that the Navy should be in such lunatic hands at this time". (96) The leader of the Conservative Party, Andrew Bonar Law was also highly critical of the Antwerp operation, describing it as "an utterly stupid business" and suggested that Churchill as having an "entirely unbalanced mind". (97) Chris Wrigley commented that "there was still something of the Boys' Hero in his behaviour." (98)

Winston Churchill was one of the first to realise that the First World War would last for several years. He was especially concerned about the stalemate on the Western Front. In December, 1914 he wrote to Asquith that neither side was likely to be able to make much impression on the other, "although no doubt several hundred thousand men will be spent to satisfy the military mind on the point." He then suggested some alternative strategies to "sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders?" (99)

Churchill also took a keen interest in new technology. Soon after the war started he was told about how Colonel Ernest Swinton and Colonel Maurice Hankey, both became convinced that it was possible to produce an armoured tracked vehicle that would provide protection from machines gun fire. Colonel Swinton was sent to the Western Front to write reports on the war. After observing early battles where machine-gunners were able to kill thousands of infantryman advancing towards enemy trenches, Swinton wrote that "petrol tractors on the caterpillar principle and armoured with hardened steel plates" would be able to counteract the machine-gunner. (100)

To maintain secrecy, Swinton coined the euphemism tank, to describe the new weapon. However, he faced real problems from his boss, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State of War. His style of leadership was very authoritarian and was reluctant to experiment. Swinton later argued that after putting the idea to Kitchener without getting any support he hesitated to press too hard because he dreaded a direct order to drop it. (101)

Churchill became very interested in this project and according to Boris Johnson, the author of The Churchill Factor (2014) he became part of the development team. He suggested that an experiment should be performed. He suggested that they should "take two steam rollers and yoke them together with long steel rods... so that they are to all intents and purposes one roller covering a breadth of at least 12 to 14 feet." Johnson argues that "this is Churchill at his dizzing best... An idea was being born. Perhaps without even knowing it, he was describing caterpillar tracks". (102)

Richard Hornsby & Sons also worked on the project and eventually produced the Killen-Strait Armoured Tractor. The tracks consisted of a continuous series of steel links, joined together with steel pins. The Killen-Strait was tested out in front of Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George at Wormwood Scrubs. The machine successfully cut through barbed wire entanglements. Churchill became convinced that this new machine would enable trenches to be crossed quite easily. (103)

Colonel Ernest Swinton persuaded the newly-formed Inventions Committee to spend money on the development of a small land-ship. and drew up specifications for this new machine. This included: (i) a top speed of 4 mph on flat ground; (ii) the capability of a sharp turn at top speed; (iii) a reversing capability; (iv) the ability to climb a 5-foot earth parapet; (v) the ability to cross a 8-foot gap; (vi) a vehicle that could house ten crew, two machine guns and a 2-pound gun. Winston Churchill wrote to H. H. Asquith, the prime minister about Swinton's ideas. (104)

Winston Churchill arranged for the Admiralty to spend £70,000 on building an experimental "land ship" (Swinton insisted on calling them tanks). A month later Churchill agreed that eighteen prototypes should be built (six were to have wheels and twelve tracks). However, most of the major work was undertaken by the War Office and Ministry of Munitions. (105)

Churchill was also concerned about the threat that Turkey posed to the British Empire and feared an attack on Egypt. He suggested that the seizure of the Dardanelles (a 41 mile strait between Europe and Asiatic Turkey that were overlooked by high cliffs on the Gallipoli Peninsula). At first the plan was initially rejected by H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Admiral John Fisher and Lord Kitchener. Churchill did manage to persuade the commander of the British Mediterranean Squadron, Vice Admiral Sackville Carden, that the operation would be successful. (106)

On 11th January 1915, Vice Admiral Carden proposed a three-stage operation: the bombardment of the Turkish forts protecting the Dardanelles, the clearing of the minefields and then the invasion fleet travelling up the Straits, through the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople. Carden argued that to be successful the operation would need 12 battleships, 3 battle-cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 16 destroyers, six submarines, 4 sea-planes and 12 minesweepers. Whereas other members of the War Council were tempted to change their minds on the subject, Admiral Fisher threatened to resign if the operation took place. (107)

Admiral Fisher wrote to Admiral John Jellicoe, Commander of the Grand British Fleet, arguing: "I just abominate the Dardanelles operation, unless a great change is made and it is settled to be made a military operation, with 200,000 men in conjunction with the Fleet." (108) Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, agreed with Fisher and circulated a copy of the Committee of Imperial Defence assessment that was against a purely naval assault on the Dardanelles. (109)

Despite these objections, Asquith decided that "the Dardanelles should go forward." On 19th February, 1915, Admiral Carden began his attack on the Dardanelles forts. The assault started with a long range bombardment followed by heavy fire at closer range. As a result of the bombardment the outer forts were abandoned by the Turks. The minesweepers were brought forward and managed to penetrate six miles inside the straits and clear the area of mines. Further advance up into the straits was now impossible. The Turkish forts were too far away to be silenced by the Allied ships. The minesweepers were sent forward to clear the next section but they were forced to retreat when they came under heavy fire from the Turkish batteries. (110)

Winston Churchill became impatient about the slow progress that Carden was making and demanded to know when the third stage of the plan was to begin. Admiral Carden found the strain of making this decision extremely stressful and began to have difficulty sleeping. On 15th March, Carden's doctor reported that the commander was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Carden was sent home and replaced by Vice-Admiral John de Robeck, who immediately ordered the Allied fleet to advance up the Dardanelles Straits. (111) Reginald Brett, who worked for the War Council, commented: "Winston is very excited and jumpy about the Dardanelles; he says he will be ruined if the attack fails." (112)

On 18th March eighteen battleships entered the straits. At first they made good progress until the French ship, Bouvet struck a mine, heeled over, capsized and disappeared in a cloud of smoke. Soon afterwards two more ships, Irresistible and Ocean hit mines. Most of the men in these two ships were rescued but by the time the Allied fleet retreated, over 700 men had been killed. Overall, three ships had been sunk and three more had been severely damaged. Altogether about a third of the force was either sunk or disabled. (113)

At an Admiralty meeting on 19th March, Churchill and Fisher agreed that losses were only to be expected and that four more ships should be sent out to reinforce De Robeck, who responded with the news that he was reorganising his force so that some of the destroyers could act as minesweepers. Churchill now told Asquith that he was still confident that the operation would be successful and was "fairly pleased" with the situation. (114)

On 10th March, Lord Kitchener finally agreed that he was willing to send troops to the eastern Mediterranean to support any naval breakthrough. Churchill was able to secure the appointment of his old friend, General Ian Hamilton, as Commander of the British Forces. At a conference on 22nd March on board his flagship, Queen Elizabeth, it was decided that soldiers would be used to capture the Gallipoli peninsula. Churchill ordered De Roebuck to make another attempt to destroy the forts. He rejected the idea and said that the idea that the forts could be destroyed by gunfire had "conclusively proved to be wrong". Admiral Fisher agreed and warned Churchill: "You are just eaten up with the Dardanelles and can't think of anything else! Damn the Dardanelles! they'll be our grave." (115)

Arthur Balfour suggested delaying the landings. Churchill replied: "No other operation in this part of the world could ever cloak the defeat of abandoning the effort at the Dardanelles. I think there is nothing for it but to go through with the business, and I do not at all regret that this should be so. No one can count with certainty upon the issue of a battle. But here we have the chances in our favour, and play for vital gains with non-vital stakes." He wrote to his brother, Major Jack Churchill, who was one of those soldiers about to take part in the operation: "This is the hour in the world's history for a fine feat of arms, and the results of victory will amply justify the price. I wish I were with you." (116)

Asquith, Kitchener, Churchill and Hankey held a meeting on 30th March and agreed to go ahead with an amphibious landing. Leaders of the Greek Army informed Kitchener that he would need 150,000 men to take Gallipoli. Kitchener rejected the advice and concluded that only half that number was needed. Kitchener sent the experienced British 29th Division to join the troops from Australia, New Zealand and French colonial troops on Lemnos. Information soon reached the Turkish commander, Liman von Sanders, about the arrival of the 70,000 troops on the island. Sanders knew an attack was imminent and he began positioning his 84,000 troops along the coast where he expected the landings to take place. (117)

The attack that began on the 25th April, 1915 established two beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe. Another major landing took place at Sulva Bay on 6th August. By this time they arrived the Turkish strength in the region had also risen to fifteen divisions. Attempts to sweep across the peninsula by Allied forces ended in failure. By the end of August the Allies had lost over 40,000 men. General Ian Hamilton asked for 95,000 more men, but although supported by Churchill, Lord Kitchener was unwilling to send more troops to the area. (118)

Frances Stevenson reported that King George V had become concerned about Churchill's drinking. "The Dardanelles campaign, however, does not seem to be the success that was prophesied. Churchill very unwisely boasted at the beginning, when things were going well, that he had undertaken it against the advice of everyone else at the Admiralty... LG (David Lloyd George) says Churchill is very worried about the whole affair, and looking very ill. He is very touchy too. Last Monday LG was discussing the Drink question with Churchill, and Samuel and Montague were also present. Churchill put on the grand air, and announced that he was not going to be influenced by the King, and refused to give up his liquor - he thought the whole thing was absurd. LG was annoyed, but went on to explain a point that had been brought up. The next minute Churchill interrupted again. 'I don't see' - he was beginning, but LG broke in sharply: 'You will see the point', he rapped out, 'when you begin to understand that conversation is not a monologue!' Churchill went very red, but did not reply, and LG soon felt rather ashamed of having taken him up so sharply, especially in front of the other two." (119)

In the words of one historian, "In the annals of British military incompetence Gallipoli ranks very high indeed." (120) Churchill was blamed for the failed operation and Asquith told him he would have to be moved from his current post. Asquith was also involved in developing a coalition government. The Conservative leader, Andrew Bonar Law, insisted that Churchill should be removed from the War Cabinet. James Masterton-Smith, Churchill's private secretary, told Asquith, that "on no account ought Churchill to be allowed to remain at the Admiralty - he was most dangerous there". (121) Asquith agreed and Churchill's long-term enemy, Arthur Balfour, became the new First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill was now relegated to the post of the Chancellorship of the Duchy of Lancaster. (122)

On 14th October, Hamilton was replaced by General Charles Munro. After touring all three fronts Munro recommended withdrawal. Lord Kitchener, initially rejected the suggestion but after arriving on 9th November 1915 he visited the Allied lines in Greek Macedonia, where reinforcements were badly needed. On 17th November, Kitchener agreed that the 105,000 men should be evacuated and put Munro in control as Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean. (123)

About 480,000 Allied troops took part in the Gallipoli campaign, including substantial British, French, Senegalese, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. The British had 205,000 casualties (43,000 killed). There were more than 33,600 ANZAC losses (over one-third killed) and 47,000 French casualties (5,000 killed). Turkish casualties are estimated at 250,000 (65,000 killed). "The campaign is generally regarded as an example of British drift and tactical ineptitude." (124)

In November, 1915, Churchill was removed as a member of the War Council. He now resigned as a minister and he told Asquith that his reputation would rise again when the whole story of the Dardanelles came out. He also criticised Asquith in the way the war had so far been managed. He ended his letter with the words: "Nor do I feel in times like these able to remain in well-paid inactivity. I therefore ask you to submit my resignation to the King. I am an officer, and I place myself unreservedly at the disposal of the military authorities, observing that my regiment is in France." (125)

Winston Churchill rejoined the British Army and on 18th November, 1915, he arrived in France. Edward V. Lucas wrote in his satirical column in The Star: "Mr Winston Churchill leaves for the front. Panic among the enemy." He was given command of a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. They were resting some miles behind the front line, trying to recover strength and morale after suffering terrible losses at Loos. He did not see any action and this brief period of active service was twice broken by weeks of leave: 2nd - 13th March and 19th - 27th April. On 6th May he was given permission to return to his parliamentary duties. (126)

Primary Sources

(1) Winston Churchill, letter to Clementine Hozier (27th April 1908)

The Conservative Party is filled with old doddering peers, cute financial magnates, clever wirepullers, big brewers with bulbous noses. All the enemies of progress are there - weaklings, sleek, slug, comfortable, self-important individuals.

(2) Winston Churchill, My African Journey (1908)

Armed with a superior religion and strengthened with Arab blood, they maintain themselves without difficulty at a far higher level than the pagan aboriginals among whom they live... I reflected upon the interval that separates these two races from each other, and on the centuries of struggle that the advance had cost, and I wondered whether the interval was wider and deeper than that which divides the modern European from them both.

(3) Winston Churchill, letter to H. H. Asquith (April 1908)

My opinion on the Irish question has ripened during the last two years, when I have lived in the inner counsels of Liberalism. I have become convinced that a 'national settlement of the Irish difficulty on broad and generous lines is indispensable to any harmonious conception of Liberalism - the object lesson is South Africa.

(4) Winston Churchill, letter to letter to Clementine Churchill (30th May 1909)

These military men very often fail altogether to see the simple truths underlying the relationships of all armed forces, & how the levers of power can be used upon them. Do you know I would greatly like to have some practice in the handling of large forces. I have much confidence in my judgment on things, when I see clearly, but on nothing do I seem to feel the truth more than in tactical combinations. It is a vain and foolish thing to say - but you will not laugh at it. I am sure I have the root of the matter in me - but never I fear in this state of existence will it have a chance of flowering - in bright red blossom.

(5) Winston Churchill, Liberalism and the Social Problem (1909)

The more I think about it, the more it appeals to my sense of justice and to my notions of policy... its possession land by private people is undesirable... It may be in the public interest, and certainly it is in the public mood, that great estates should be broken up; but it cannot be in anybody's interest that they should merely be encumbered. The reduction, paring off, or division of large landed properties may easily be attended with an increase of population and prosperity in the district affected. But to have great landed estates strictly entailed, drifting about in a sort of waterlogged condition, only kept afloat by grinding economies and starvation of development, must be attended in this country, as in Ireland, with severe evils to the rural population... we must, I take it, view with favour all transferences of land to the State. We shall require, as the years go by, a continued supply of land, spread about all over the country... All comes back to the land; and in proportion as the State is the owner of the land, so in the passage of years, all will come back to the State...

I want things done. I want dreams, but dreams that are realizable. I want aspiration and discontent leading to a real paradise and a real earth in which men can live here and now, and fulfil the destiny of the human race. I want to make life better and kinder and safer - now at this moment. Suffering is too close to me. Misery is too near and insistent. Injustice is too obvious and glaring. Danger is too present.

(6) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (17th December, 1909)

When I began my campaign in Lancashire I challenged any Conservative speaker to come down and say why the House of Lords... should have the right to rule over us, and why the children of that House of Lords should have the right to rule over our children. My challenge has been taken up with great courage by Lord Curzon. No, the House of Lords could not have found any more able and, I will add, any more arrogant defender... His claim resolves itself into this, that we should maintain in our country a superior class, with law-giving functions inherent in their blood, transmissible by them to their remotest posterity, and that these functions should be exercised irrespective of the character, the intelligence or the experience of the tenant for the time being and utterly independent of the public need and the public will... Now I come to the third great argument of Lord Curzon... "All civilization has been the work of aristocracies." Why, it would be much more true to say the upkeep of the aristocracy has been the hard work of all civilizations.

(7) Winston Churchill, Thoughts and Adventures (1932)

No one can have worked as closely as I have with Mr Lloyd George without being both impressed and influenced by him. The reputation which he has long enjoyed as a parliamentary and platform speaker has often been an exaggerated one. Extraordinary as have been his successes in public, it is in conclaves of eight or nine, or four or five, or in personal discussion man to man, that his persuasive arts reach their fullest excellence. At his best he could almost talk a bird out of a tree. An intense, comprehension of the more amiable weaknesses of human nature: a pure gift of getting on the right side of a man from the beginning of a talk: a complete avoidance of anything in the nature of chop-logic reasoning: a sure, deft touch in dealing with realities: the sudden presenting of positions hitherto unexpected, but apparently conciliatory and attractive - all these are models and methods in which he is a natural adept. I have seen him turn a Cabinet round in less than ten minutes, and yet when the process was complete, no one could remember any particular argument to which to attribute their change of view. He has realized with intense comprehension the truth of the adage "A man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still". He never in the days when I knew him best thought of giving himself satisfaction by what he said. He had no partiality for fine phrases, he thought only and constantly of the effect produced upon other persons.

(8) Robert Lloyd George, David & Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2005)