On this day on 29th March

On this day in 1584 General Ferdinando Fairfax was born. He became a large landowner in Yorkshire and was elected to the House of Commons as a representative for Boroughbridge and served during the six parliaments which met between 1614 and 1629.

In May 1640 he succeeded his father as Lord Fairfax, but as a Scottish peer he was able to sit in the House of Commons and was one of the representatives of Yorkshire during the Long Parliament from 1640 until his death.

An opponent of Charles I, on the outbreak of the Civil War he joined the Parliamentary forces. In 1642 was appointed commander of the northern army and led the infantry at Marston Moor in 1644.

In February 1645, Fairfax's son, Thomas Fairfax, became commander of the New Model Army. Soon afterwards Fairfax was appointed Governor of York. Fairfax held this post until he died from an accident which caused gangrene in his foot on 14th March 1652.

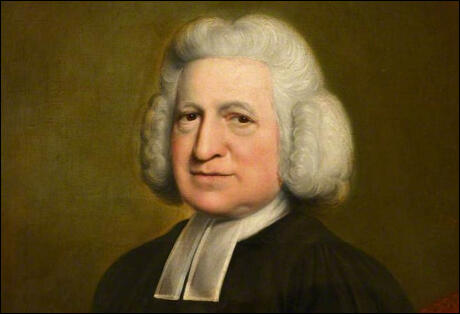

On this day in 1788 English missionary Charles Wesley died. Wesley, the son of the rector of Epworth, Lincolnshire, was born on 18th December 1707. He studied at Christ College, Oxford, and became a member of a religious group that included his brother, John Wesley and George Whitefield. The group became became known as the Holy Club or the Oxford Methodists.

In 1735 Charles and John Wesley became missionaries in Georgia, America. They returned to England five years later and for the rest of his life Charles became the able lieutenant to his more charismatic brother. Charles wrote over 5,500 hymns, including the popular Jesu, Lover of My Soul and Hark, the Herald Angels Sing.

On this day in 1826 Wilhelm Liebknecht, the son of Katharina Elisabeth Henrietta and Ludwig Christian Liebknecht, was born in Gießen. His parents died when he was a child and he was raised by relatives. He went to a local school before studying philology, theology and philosophy in Berlin and Marburg.

In 1847 he became a teacher of a progressive school in Zurich. Later that year a civil war erupted in Switzerland. He sent eyewitness reports to the German newspaper, The Mannheimer Abendzeitung.

Liebknecht now decided to become a journalist. He went to Paris in 1848 to report on the uprising. He then moved onto Germany but was arrested in Baden and charged with treason. However, a mob secured his release. He escaped to Switzerland and became a leading member of the Worker's Association in Geneva. Now a committed revolutionary, Liebknecht activities eventually got him banished from the country.

In 1850 Liebknecht moved to London, where he associated with other socialists such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, George Julian Harney, Ernest Jones and Robert Owen. Liebknecht, Marx and Engels became members of the Communist League. He later recalled: "During the thirteen years I spent in England I learnt to know the English workers and to love them. Far from looking askant at the foreigner, they have, on the contrary, a considerate sympathy with him, which seemed to me not infrequently excessive... The great heart of the English workers has never failed. Wherever there has been fighting for the cause of labour and humanity, there were the true, sincere, and, where need was, the practical sympathies of the English workers."

After the amnesty for the participants in the revolution of 1848, Liebknecht moved back to Germany and joined the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), that had been formed by Ferdinand Lassalle. Liebknecht moved to Leipzig where he met August Bebel. The two men became close friends. Bebel later recalled: "Liebknecht’s genuine fighter’s nature was keyed up by an impregnable optimism, without which no great aim can be accomplished. No blow that struck him, personally or the party, could rob him for a minute of his courage or of his composure. Nothing took him unawares; he always knew a way out. Against the attacks of his antagonists his watchword was: Meet one rascal by one and a half. He was harsh and ruthless against our opponents, but always a good comrade to his friends and associates, ever trying to smooth over existing difficulties."

Over the next few years the worked together in an effort to spread the ideas of Karl Marx. In 1868 he won a seat in the Reichstag. In his book, On The Political Position of Social-Democracy (1869), he explained: "The question as to what position Social-Democracy should occupy in the political fight, can be answered easily and confidently if we clearly understand that socialism and democracy are inseparable. Socialism and democracy are not identical, but they are simply different expressions of the same principle; they belong together, supplement each other, and one can never be incompatible with the other. Socialism without democracy is pseudo-socialism, just as democracy without socialism is pseudo-democracy. The democratic state is the only feasible form for a society organized on a socialist basis.... We call ourselves Social-Democrats, because we have understood that democracy and socialism are inseparable. Our programme is implied in this name. But a programme is not designed to be given merely lip-service and to be repudiated in action. It should be the standard which determines our conduct."

In 1869 Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel formed the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) together. They also established a newspaper, Der Volksstaat. In 1870 the two men used the newspaper to promote the idea that Otto von Bismarck had provoked France into war and called on workers from both countries to unite in overthrowing the ruling class. As a result, Bebel and Liebknecht were arrested and charged with high treason. In 1872, both men were convicted and sentenced to two years in the Königstein Fortress.

On his release in 1874 Liebknecht was once again elected to the Reichstag. The following year he helped the SDAP merge with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned Social Democratic Party meetings and publications.

Paul Frölich was a member of SDP who was critical of Liebknecht's leadership. He argued: "In the German social-democratic movement the policy of repudiating the use of violence in the political struggle had become practically a dogma. Wilhelm Liebknecht, whose tongue often enough ran ahead of his ideas, had once declared that violence only served reactionary ends - a remark which was repeated with gusto on every possible occasion."

After the anti-socialist law ceased to operate in 1890, the SDP grew rapidly. However, Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel had problems with divisions in the party. Eduard Bernstein, a member of the SDP, who had been living in London, became convinced that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands. Bernstein's revisionist views appeared in his extremely influential book Evolutionary Socialism (1899). His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

Liebknecht also had trouble from the left of the SDP. He came into conflict with Rosa Luxemburg over her militant articles in Vorwarts. Her biographer, Paul Frölich, has pointed out in his book, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940): "When Luxemburg published her articles on the Oriental question, even old Wilhelm Liebknecht set upon her with a letter which failed to refute any of her arguments, but which let fly at her a whole quiver of choice invectives, going so far as to make the scarcely veiled accusation that she had been bought by the Russian Okhrana - an action which, somewhat later, the old man admitted to be wrong and regretted."

Wilhelm Liebknecht died in Charlottenburg on 7th August 1900.

On this day in 1895 Ernst Jünger, the son of a wealthy chemist, was born in Heidelburg, Germany. At the age of seventeen he ran away from home to join the Foreign Legion. His father brought him back but he returned to military service when he joined the German Army on the outbreak of the First World War.

Jünger fought on the Western Front and was wounded at Les Epares in 1915. He recovered and in November he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. After the Battle of the Somme Jünger was awarded the Iron Cross and is transferred to Divisional Intelligence as a reconnaissance officer.

In 1917 Jünger fought at Cambrai and later that year is wounded while leading an attack on French trenches. After recovering from his injuries he took part in the Spring Offensive. After leading another attack, for which he won the Pour le Merite, he was seriously wounded, he spent the rest of the war in a military hospital.

In 1920 Jünger published his first book, The Storm of Steel. Its glorification of war made it a popular with Germany's young people who dreamed of gaining revenge after the country's disastrous defeat in 1918.

Ernst Jünger studied zoology, geology and botany before becoming a full-time writer. His books included Das Abenteurliche Herz (1929) and Der Arbeiter (1932).

His work was very popular with members of the Nazi Party and after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 he was offered a seat in the Reichstag. Although he supported the party he refused the offer and concentrated on his writing. His later books included and Blatter und Steine (1934) and On the Marble Cliffs (1939).

Jünger joined the German Army on the outbreak of the Second World War and served on the staff of the military command in occupied France where he was involved in the planning of Operation Sealion. In 1942 was transferred to the Soviet Union.

Jünger became increasingly critical of the atrocities committed by the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) in occupied Europe and was dismissed from the army after the July Plot. His son, who was also in the army, was arrested for organizing subversive discussions in his unit. After being found guilty he was sent to a punishment battalion and was killed in Carrara in Italy in November, 1944.

His criticisms of Adolf Hitler and his totalitarian system, appeared in his book The Peace (1948). His war diaries, Strahlungen (1949) were also critical of Nazi Germany. Jünger also published the novels Heliopolis (1949), Die Eberjagd (1952), Besuch auf Goldenholm (1952), Zie Zwille (1973) and Eumeswil (1977). Ernst Jünger died on 17th February, 1998.

On this day in 1930 Franklin Roosevelt, the Governor of New York, made an important speech on unemployment. He disagreed with President Herbert Hoover when he vetoed a bill that would have created a federal unemployment agency. Hoover also opposed a plan to create a public works programme. In March, 1930, Roosevelt established a commission to stabilize employment in New York. "The situation is serious and the time has come for us to face this unpleasant fact dispassionately".

Unemployment which stood at 4 million in March 1930, reached 8 million in March 1931. Hoovervilles, settlements on tin shacks, abandoned cars and discarded packing crates, emerged on the edges of all big cities. President Hoover responded by urging Americans to embrace the principles of local responsibility and mutual self-help, by setting up community soup kitchens. If we depart from these principles, he argued, we will "have struck at the roots of self-government".

Roosevelt made it clear that he disapproved of this approach to unemployment. He pointed out he was willing to spend $20 million to provide useful work where possible and, where such work could not be found, to provide the needy with food and shelter. "In broad terms I assert that modern society, acting through its government, owes the definite obligation to prevent the starvation or dire want of any of its fellow men and women who try to maintain themselves but cannot... To these unfortunate citizens aid must be extended by government - not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty."

In addition to the $20 million relief package, Roosevelt asked the New York legislature, for funds to establish a new state agency, the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), to distribute the funds. He also requested that the legislature to raise personal income taxes by 50% to pay for the relief effort. New York was the first state to establish a relief agency, and TERA immediately became a model for other states. This included New Jersey, Rhode Island and Illinois.

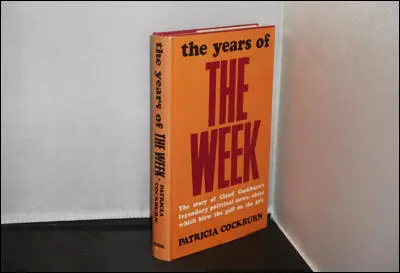

On this day in 1933 Claud Cockburn started publishing the anti-fascist newsletter, This Week. Cockburn got the idea for his newsletter while working in New York City where he saw for the first time a mimeograph machine. He later recalled: "A mimeograph machine is one of the few remaining weapons which still gives small and comparatively poor organizations a sporting chance in a scrap with large and wealthy ones."

This impression was reinforced in Germany where he had seen supporters of Kurt von Schleicher using mimeograph machines to produce political propaganda. Cockburn had also been inspired by the French satirical paper Le Canard Enchainé. He considered it "the best-informed publication in France" and although some of it was "in execrable taste" it carried no advertisements, received no subsidies, and still broke "a little better than even". Cockburn was also attracted to the way it exposed government corruption. Something that Cockburn was keen on doing in Britain.

As Richard Ingrams has explained: "Started on a capital of £50 provided by his Oxford friend Benvenuto Sheard, the paper, which was all his own work, was produced in a one-room office at 34 Victoria Street, and was obtainable only by subscription. Although he relied on information supplied by a number of foreign correspondents including Negley Farson (Chicago Daily News) and Paul Scheffer (Berliner Tageblatt), it was his own journalistic flair which gave the paper its unique influence. Cockburn was not an orthodox journalist. He pooh-poohed the notion of facts as if they were nuggets of gold waiting to be unearthed. It was, he believed, the inspiration of the journalist which supplied the story. Speculation, rumour, even guesswork, were all part of the process and an inspired phrase was worth reams of cautious analysis."

The first issue of the newsletter appeared on Wednesday, 29th March 1933. As Norman Rose has pointed out: "It was preceded by scenes of great editorial confusion. The actual production of the paper was left until Wednesday morning in order, Claud argued, to pre-empt the existing weeklies with as much hot ness as possible. Claud wrote the entire issue - a modest three pages of foolscap - and cut the stencils, touching up the material as he progressed, a routine that excluded any prospect of efficiency... The Week finally emerged in what would become its distinctive format, smudgy in appearance, lively in content." The first edition had as its lead story "Black-Brown-Fascist Plan". It told of how Benito Mussolini had sponsored a four-power arrangement to regulate the affairs of Europe. It revealed that a definite proposal had been forwarded to London and Warsaw that envisaged granting concessions to Germany in the Polish Corridor while compensating Poland with a slice of Russian Ukraine."

Claud Cockburn relied on other journalists to supply most of his information. These were those stories that their own newspaper would not print. Important contacts included Frederick Kuh, Negley Farson, Paul Scheffer and Stefan Litauer. Another source was the secretary of Von Papen. According to Jessica Mitford: "In the early thirties Claud Cockburn founded and wrote a mimeographed political muckraking journal called The Week which, in the period immediately preceding the war, had become extraordinarily influential. The Week was packed with riveting inside stories garnered from undercover sources throughout Europe - at one time, Claud's principal informant in Berlin (his Deep Throat, so to speak) was secretary to Herr von Papen, a member of Hitler's cabinet."

A close friend, Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman, claimed that many of the stories that appeared in The Week had already reached him in the "form of rumour" but unable to confirm their veracity, he would not risk publishing them. Cockburn did publish them. He once pointed out: "How can one tell truth from rumour in less than perhaps fifty years?" Cockburn was warned that this approach could get him into a lot of trouble. John Wheeler-Bennett warned him that very soon he would be "either quite famous or in gaol." Richard Ingrams has admitted: "In other hands it might have been a fatal approach, but Cockburn had great flair, and although many stories in The Week were fanciful, there was enough important information to win it an influence out of all proportion to its circulation."

James Pettifer has argued: "The Week... was almost exclusively concerned with the life of the ruling classes in the different European countries, and exposing inner machinations to a wider public, but they remained conspiracies that took place in drawing-rooms, in banks, in clubs and in the officers' messes... The Week... soon became famous for its exposure of the machinations of the Conservative government in the later years of the decade. More than anything else published at the time, The Week brought home to its subscribers the nature of Appeasement, and how a dominant section of the Conservative Party was assisting the foreign policy of the fascist dictators"

Cockburn was soon being monitored by MI5. In a report written on 2nd November 1933, an agent went to see Cockburn and claimed he wanted to write for The Week. He later reported: "He swallowed my story and asked for an article, which I shall prepare today. He is either very crafty or very gullible, for he invited me to have a boozing evening with him, which I cannot unfortunately afford to do, and therefore invented an appointment." A report written the following year states: "I am informed that so much is thought of the ability of F. Claud Cockburn that he could return to the staff of The Times any day he wished, if he would keep his work to the desired policy of this newspaper."

Cockburn's main target was those members of the ruling elite who were proponents of appeasement. He relied on people within the corridors of power for his information. One source was probably Robert Vansittart, Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office. When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor on 30th January 1933, Vansittart became his leading opponent in the Foreign Office. He wrote on 6th May: "The present regime in Germany will, on past and present form, loose off another European war just so soon as it feels strong enough … we are considering very crude people, who have very few ideas in their noddles but brute force and militarism."

Vansittart worked very closely with Admiral Hugh Sinclair, the head of MI6, and Vernon Kell, the head of MI5. According to Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "Robert Vansittart, permanent under secretary at the Foreign Office, was much more interested in intelligence than his political masters were... He dined regularly with Sinclair, was also in (less frequent) touch with Kell, and built up what became known as his own private detective agency collecting German intelligence. More than any other Whitehall mandarin, Vansittart stood for rearmament and opposition to appeasement."

Robert Vansittart also recruited his own spies. This included Jona von Ustinov, a German journalist working in London. However, his most important spy was Wolfgang zu Putlitz, First Secretary at the German Embassy, and a friend of Cockburn from the time he worked in Berlin in the 1920s. Putlitz later recalled: "I would unburden myself of all the dirty schemes and secrets which I encountered as part of my daily routine at the Embassy. By this means I was able to lighten my conscience by the feeling that I was really helping to damage the Nazi cause for I knew Ustinov was in touch with Vansittart, who could use these facts to influence British policy." Putlitz insisted that the only way to deal with Adolf Hitler was to stand firm.

Cockburn wrote a great deal in The Week about what became known as the Cliveden Set. The leaders of this group, Nancy Astor and her husband, Waldorf Astor, held regular weekend parties at their home Cliveden, a large estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames. Those who attended included Philip Henry Kerr (11th Marquess of Lothian), Edward Wood (1st Earl of Halifax), Geoffrey Dawson, Samuel Hoare, Lionel Curtis, Nevile Henderson, Robert Brand and Edward Algernon Fitzroy. Most members of the group were supporters of a close relationship with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. The group included several influential people. Astor owned The Observer, Dawson was editor of The Times, Hoare was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Halifax was a minister of the government who would later become foreign secretary and Fitzroy was Speaker of the Commons.

In 1935 a Colonel Valentine Vivian, the head of counter-espionage at MI6, wrote to Captain Guy Liddell at MI5 saying he had sent MI6's man in Berlin to talk to Norman Ebbutt, who had worked with him at The Times in the 1920s. The agent reported the conversation: "Ebbutt has the highest opinion of Claud Cockburn's honesty and admires him for feeding on the crust of an idealist when he could obtain a fat appointment by being untrue to himself... Ebbutt says The Week has a large circulation among businessmen in the City. He gets his copy regularly. He very much regrets that Claud Cockburn has now completely fallen to the mad idea that all Imperialists dream of nothing but the destruction of Russia."

Norman Rose, the author of The Cliveden Set (2000) has pointed out: "Lothian, Dawson, Brand, Curtis and the Astors - formed a close-knit band, on intimate terms with each other for most of their adult life. Here indeed was a consortium of like-minded people, actively engaged in public life, close to the inner circles of power, intimate with Cabinet ministers, and who met periodically at Cliveden or at 4 St James Square (or occasionally at other venues). Nor can there be any doubt that, broadly speaking, they supported - with one notable exception - the government's attempts to reach an agreement with Hitler's Germany, or that their opinions, propagated with vigour, were condemned by many as embarrassingly pro-German."

On 17th June, 1936, Claud Cockburn, produced an article called "The Best People's Front" in his anti-fascist newsletter, The Week. He argued that a group that he called the Astor network, were having a strong influence over the foreign policies of the British government. He pointed out that members of this group controlled The Times and The Observer and had attained an "extraordinary position of concentrated power" and had become "one of the most important supports of German influence". Over the next year he continually reported on what was said at weekends at Cliveden. It is not known who was providing him with this detailed information.

On a visit to the United States Anthony Eden was amazed when he discovered the impact on public opinion of articles on the Cliveden Set in The Week was having in the country. A horrified Eden reported to Stanly Baldwin that "Nancy Astor and her Cliveden Set has done much damage, and 90 per cent of the US is firmly persuaded that you (Baldwin) and I are the only Tories who are not fascists in disguise."

In the spring of 1937, Sir Vernon Kell, the head of MI6 wrote a note to a diplomat at the American Embassy saying: "Cockburn is a man whose intelligence and wide variety of contacts make him a formidable factor on the side of Communism." Kell complained that The Week was full of gross inaccuracies and was written from a left-wing point of view, but admitted that on occasions "he is quite well informed and by intelligent anticipation gets quite close to the truth". Kell was also concerned about some accurate reports that appeared in The Week about King Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson.

In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain sent Lord Halifax in secret to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Goering in Germany. In his diary, Lord Halifax records how he told Hitler: "Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country." This was a reference to the fact that Hitler had banned the Communist Party (KPD) in Germany and placed its leaders in Concentration Camps. Halifax had told Hitler: "On all these matters (Danzig, Austria, Czechoslovakia)..." the British government "were not necessarily concerned to stand for the status quo as today... If reasonable settlements could be reached with... those primarily concerned we certainly had no desire to block."

The story was leaked to the journalist Vladimir Poliakoff. On 13th November 1937 the Evening Standard reported the likely deal between the two countries: "Hitler is ready, if he receives the slightest encouragement, to offer to Great Britain a ten-year truce in the colonial issue... In return... Hitler would expect the British Government to leave him a free hand in Central Europe". On 17th November, Claude Cockburn reported in The Week, that the deal had been first moulded "into usable diplomatic shape" at Cliveden that for years has "exercised so powerful an influence on the course of British policy."

It was claimed that the circulation of The Week reached 40,000 at the height of its fame. Cockburn pointed out it was read by important people: "Foreign Ministers of eleven nations, all the embassies and legations in London, all diplomatic correspondents of the principal newspapers stationed in London, the leading banking and brokerage houses in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and New York, a dozen members of the United States Senate, twenty or thirty members of the House of Representatives, about fifty members of the House of Commons and a hundred or so in the House of Lords, King Edward VIII, the secretaries of most of the leading Trade Unions, Charlie Chaplin and the Nizam of Hyderabad." Other readers included Léon Blum, William Borah, Joseph Goebbels and Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler's ambassador in London, who called for its suppression because of its anti-Nazi stance.

January 1938 Robert Vansittart was "kicked upstairs, assuming the high-sounding, but politically meaningless, title of chief diplomatic adviser to the government". His replacement was Alexander Cadogan, a member of the Cliveden Set. When Anthony Eden resigned as Foreign Secretary on 25th February, 1938, he was replaced by another Cliveden regular, Lord Halifax. Cockburn argued that the "appeasement coup" had been organised by the Cliveden Set. He later added that Halifax was "the representative of Cliveden and Printing House Square rather than of more official quarters."

On the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 the government suppressed the Daily Worker and The Week, although they were both later allowed to resume publication once the Soviet Union became one of the allies. According to his biographer, Richard Ingrams: "The new situation, which conferred respectability on the communists, was not to Cockburn's liking, and his Marxist fervour began to wane. He was further influenced by an interview with Charles de Gaulle in Algeria in 1943, in which the general suggested that his loyalty to the communist movement might perhaps be ‘somewhat romantic’. Following the Labour victory in 1945 he became convinced that the communists were ineffective as a political force."

On this day in 1970 Anna Louise Strong died. Anna, the daughter of Sydney Dix Strong, was born on 24th November, 1885 in Friend, Nebraska. Her father was a minister in the Congregational Church and was active in missionary work.

Strong attended Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and Oberlin College in Ohio. In 1908 she received a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Chicago. She developed left-wing opinions and was active in politics and was elected to the Seattle School Board in 1916. She argued that the public schools should offer social service programs for underprivileged children but she got very little support from other members of the board.

In 1916 she was commissioned by the New York Evening Post to report on the industrial dispute between the Industrial Workers of the World and employers in Everett, Washington. On 5th November, 1916, a shoot-out took place between 200 vigilantes (citizen deputies) and the IWW. Five strikers were killed and another 27 were wounded. Two vigilantes were killed but it was later discovered they were actually shot in the back by fellow deputies. Strong was appalled by this violence and became a supporter of the IWW and contributed material for its various publications using the pseudonym "Anise".

Strong and the IWW opposed the United States becoming involved in the First World War. However, William Haywood, the IWW leader, did not agitate against it nor forbid members to comply with the draft. Nevertheless, politicians and employers' associations attacked the IWW as disloyal and dangerous. In a series of raids resulted in the indictment of Haywood and most of the union's leadership under the Espionage Act. After a long trial in Chicago, Haywood was sentenced to a fine of $20,000 and twenty years' imprisonment.

Strong, like most people on the left, welcomed the Russian Revolution. In 1921 she travelled to Russia as a member of the Quaker Relief Mission. In 1922 she became the Moscow correspondent of the International News Service. Over the next few years Strong developed a reputation for being sympathetic to the Bolshevik government. Leon Trotsky praised her for supporting the New Economic Policy (NEP) that had been introduced by Lenin. "She approached the Revolution not from the aesthetic, or contemplative point of view, but from the point of view of action. Under the prose of the NEP, as well as under the dramatic events of the civil war, she was able to see, or perhaps at the very beginning, merely to feel, - the intense, stubborn, uncompromising struggle against age-long slavery, darkness, barbarism for new higher forms of life. When the Volga was stricken by famine, Miss Strong arrived in Russia for the difficult, dangerous struggle with hunger and epidemics. She herself went through typhus. In her numerous articles and correspondence, she tirelessly made breaches in that wall of reactionary lies that made the most important part of the imperialistic blockade around the Revolution. This does not mean, of course, that Miss Strong was hiding the black spots; but she tried to understand and explain to others how these facts grew out of the past in its conflict with the future."

Strong published several books on Russia including The First Time in History: Two Years of Russia's New Life

(1925), Children of Revolution; Story of the John Reed Children's Colony on the Volga (1925), New Lives for Old in Today's Russia: What Has Happened to the Common Folk of the Soviet Republic (1927), Was Lenin a Great Man? (1927), How the Communists Rule Russia (1927), Marriage and Morals in Soviet Russia (1927), How Business is Carried on in Soviet Russia (1927), Workers' Life in Soviet Russia (1927) and Red Villages: The 5-year plan in Soviet Agriculture (1932)

The journalist, Vincent Sheean, met Anna Louise Strong when she was in China with Mikhail Borodin and Rayna Prohme: "About Anna Louise (and this is strictly between us): she is a fine woman, but overpowering isn't the word for it. Nervous energy, physical strength, etc., etc., and a quite unbridled enthusiasm for every Communist fact or fancy. She nearly drove Rayna to distraction during that last week. This in spite of the fact that Anna Louise was overwhelmingly kind, efficient, and good. It was something Rayna couldn't help. She used to say to me: 'For God's sake get Anna Louise out and keep her out; I cannot bear having her in the room'. I did so as much as possible, but of course Anna Louise was very much there most of the time, or large parts of the time. For God's sake don't repeat this; I've told nobody but Bill about it; it seems rather hard on Anna Louise, who really meant so well and did so much; but the unfortunate woman has such a blustery character that one can't bear being with her much. I shared to the full Rayna's feeling about her, and was ashamed of feeling that way (as was Rayna). But there you are. Anna Louise's persecution mania (if that's what it was) was hardest of all to bear. Perhaps she has changed. In those days she thought everybody was in a conspiracy to make life difficult for her. She was terribly nervous and over-wrought, and broke into hysterics at any moment (long before we knew Rayna's illness was so serious, so it had nothing to do with that - it was only self-pity and a kind of morbid fixation on Borodin). I somehow don't think you'd get on very well with Anna Louise. Aside from all these other things, she has a remarkably superficial mind, given to statistical information of all sorts, surface materials, and incapable, usually, of going half an inch deep, except perhaps in things regarding herself. I distrust her reasoning and her conclusions, because I am familiar with the clerk-like statistical skimming of her mind."

In 1930 Strong became editor of the Moscow Daily News. Other journalists who provided material for the English language newspaper included Rose Cohen, Ralph Fox and Tom Bell. According to a British Intelligence report Cohen and her husband, Max Petrovsky, were suspected of being a spy: "Bell was instructed by his chief in the office to be very friendly with her and not to tell her that she was being watched, also to discuss her husband's arrest as often as possible and... to elicit her views on the matter. He reported that she never spoke of her husband as being guilty, and although he put it to her that he must be guilty, or implicated in some way, otherwise the OGPU would not arrest him, she always replied: An error has been made somewhere." Cohen and Petrovsky were both executed.

Malcolm Muggeridge was a journalist working in Moscow during this period and recalls meeting Strong and Walter Duranty of the New York Times, another Stalin apologist. "I withdrew to a sofa where I found myself sitting between Anna Louise Strong and Walter Duranty, the New York Times correspondent. Miss Strong was an enormous woman with a very red face, a lot of white hair, and an expression of stupidity so overwhelming that it amounted to a kind of strange beauty.... She had been around in Moscow from shortly after the Revolution, and allegedly, finding herself once in a car with Trotsky, the great man put his hand on her knee in what might have been taken as an amorous gesture."

The first ever show show trial took place in August, 1936, of Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Joseph Stalin. As Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

Anna Louise Strong defended the Great Purge: "The key to the terror, most probably, in actual, extensive penetration of the GPU by a Nazi fifth column, in many actual plots and in the impact of these on a highly suspicious man who saw his own assassination plotted and believed he was saving the Revolution by drastic purge... Stalin engineered the country's modernization ruthlessly, for he was born in a ruthless land and endured ruthlessness from childhood. He engineered suspiciously, for he had been five times exiled and must have been often betrayed. He condoned, and even authorized outrageous acts of the political police against innocent people, but so far no evidence is produced that he consciously framed them."

In 1949 Strong and her boss Mikhail Borodin were arrested by the secret police. According to Roy A. Medvedev, has argued in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971): "After the Second World War Borodin worked as editor in chief of the English-language newspaper Moscow Daily News; later he transferred to the Communist Information Bureau. Almost the entire editorial staff of the paper was arrested along with him, including the American journalist Anna Louise Strong, who was accused of espionage and expelled from the USSR." The authors of Reporting the Chinese Revolution (2007) have argued: "According to Philip Jaffe, his imprisonment was the direct result of his association with Anna Louise Strong and the enduring pro-Chinese, anti-Chiang Kai-shek sympathies he shared with her. Others assert that he was simply caught up in the anti-Jewish campaign of Stalin's later years."

Malcolm Muggeridge commented: "Whether because of this past anti-Stalinist deviation, or for some other reason, in the stormy days of the cold war even she got arrested; an item of news which, I regret to say, like Oumansky's fatal accident, gave great satisfaction among former newspaper correspondents in Moscow. Some of them even sent congratulatory telegrams signalising the glad tidings. Her incarceration proved to be brief - I imagine that even in Lubianka, her presence was burdensome."

After her release she moved to Beijing where she published a regular "Letter from China." During that time she developed a close relationship with the Chinese leadership. In an interview with Mao Zedong she discussed his views on the future: "Before the February Revolution in Russia, he said, the tsar looked very strong and terrible. But a February rain washed him away. Hitler also was washed away by the storms of history. So were the Japanese imperialists. They were paper-tigers all. The same thing would happen to all imperialists and reactionaries. Their strength lay only in the unconsciousness of the people. The consciousness of the people is the basic question. Not explosives of atom bombs but the man who handles them. He is still to be educated. After a moment, he added: Communist Parties have real power, because they awaken the people's consciousness."

On this day in 2004 Lise de Baissac died aged 98. Lise de Baissac, the sister of Claude de Baissac, was born in Mauritius on 11th May, 1905. During the Second World War they both joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

Given the code name "Marguerite", Baissac and Andrée Borrel, became the first women agents to be was parachuted into France on 24th September 1942. They landed in the village of Boisrenard close to the town of Mer.

After staying with the French Resistance for a couple of days Baissac moved to Poiters whereas Borrel went to Paris to join the new Prosper Network. Over the next few months Baissac acted as liaison officer between the Prosper, Scientist and Bricklayer networks.

As she did not have a wireless she had to travel to Paris to send and receive messages and collect funds, or to Bordeaux where Claude de Baissac was building up the large circuit, organising sabotage and providing reports on submarines and shipping.

In June 1943, the Gestapo arrested several agents involved with the Prosper network including Andrée Borrel, Francis Suttill and Gilbert Norman, but Baissac managed to escape back to England.

Baissac was dropped back into France in April 1944, to work with the Pimento Circuit run by the SOE agent Anthony Brooks. However, she came into conflict with the group (she thought they were militant socialists with political aims) and joined her brother Claude de Baissac, who had gone to Normandy to reconnoitre large landing grounds that could be held for 48 hours while airborne troops established themselves.

A British army officer later claimed: “The part she played in aiding the Maquis and the British underground movement in France cannot be too highly stressed and did much to facilitate the Maquis preparations and resistance prior to the American breakthrough in Mayenne.” According to her Special Operations Executive file: “She was the inspiration of groups on the Orne and by her initiative caused heavy losses to the Germans with tyre bursters on the roads near St Aubin-le-Desert, St Mars, and as far as Laval, Le Mans and Rennes. She also took part in several armed attacks on enemy columns."

Lise de Baissac was awarded the MBE in September, 1945. After the war she married Henri Villameur, an artist and interior decorator living in Marseilles.