On this day on 27th May

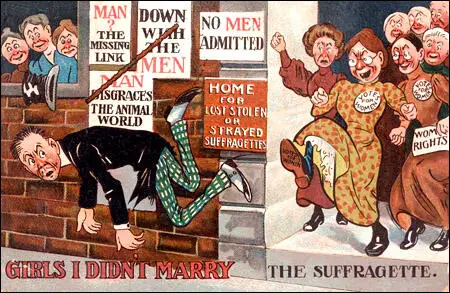

On this day in 1911 a report was published in the East Grinstead Observer about the formation of the Anti-Suffrage Society in East Grinstead.

There was a large attendance at a "At Home" held at Hurst-on-Clays, East Grinstead, by kind permission of Lady Jeannie Lucinda Musgrave on Tuesday afternoon. Mrs. Archibald Colquhoun of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League said that women had never possessed the right to vote for Members of Parliament in this country nor in any great country, and although the women’s vote had been granted in one or two smaller countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, no great empire have given women’s a voice in running the country. Women have not had the political experience that men had, and, on the whole, did not want the vote, and had little knowledge of, or interest in, politics. Politics would go on without the help of women, but the home wouldn’t.

The speaker also stated that in a recent canvas by postcard, of the 200 odd women in East Grinstead, they found that 80 did not want the vote, 40 did want the vote and the remainder would not sufficiently interested in replying. Lady Musgrave, President of the East Grinstead branch of the Anti-Suffragette League said she was strongly against the franchise being extended to women, for she did not think it would do any good whatsoever, and in sex interests, would do a lot of harm. She quoted the words of Lady Jersey: "Put not this additional burden upon us." Women were not equal to men in endurance or nervous energy, and she thought she might say, on the whole, in intellect.

On this day in 1917 Rosa Luxemburg writes about the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II. Luxemburg was in prison in Germany as a result of her anti-war activities. Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government and a few days later announced that all political prisoners would be allowed to return to their homes. She wrote to her close friend, Hans Diefenbach: "You can well imagine how deeply the news from Russia has stirred me. So many of my old friends who have been languishing in prison for years in Moscow, St Petersburg, Orel and Riga are now walking about free. How much easier that makes my own imprisonment here!"

In her prison cell she wrote several articles on the overthrow of Nicholas II. "The revolution in Russia has been victorious over bureaucratic absolutism in the first phase. However, this victory is not the end of the struggle, but only a weak beginning." She also condemned the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries who had joined the government. "The coalition ministry is a half-measure which burdens socialism with all the responsibility, without even beginning to allow it the full possibility of developing its programme. It is a compromise which, like all compromises is finally doomed to fiasco."

Luxemburg's fears were realised when Alexander Kerensky became the new prime minister and soon after taking office, he announced the July Offensive. In a long article in Spartakusbriefe she condemned Kerensky's strategy. "Although the Russian Republic professes to be fighting a purely defensive war, in reality it is participating in an imperialist one, and, while it appeals to the right of nations to self-determination, in practice it is aiding and abetting the rule of imperialism over foreign nations."

After Nicholas II abdicated, the new Provisional Government announced it would introduce a Constituent Assembly. Elections were due to take place in November. Some leading Bolsheviks believed that the election should be postponed as the Socialist Revolutionaries might well become the largest force in the assembly. When it seemed that the election was to be cancelled, five members of the Bolshevik Central Committee, Victor Nogin, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Vladimir Milyutin submitted their resignations.

Kamenev believed it was better to allow the election to go ahead and although the Bolsheviks would be beaten it would give them to chance to expose the deficiencies of the Socialist Revolutionaries. "We (the Bolsheviks) shall be such a strong opposition party that in a country of universal suffrage our opponents will be compelled to make concessions to us at every step, or we will form, together with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, non-party peasants, etc., a ruling bloc which will fundamentally have to carry out our programme."

Despite the prevailing disorders and confusion, thirty-six million cast their secret ballots in parts of the country normal enough to hold elections. In most of the large centers of population, the voting was conducted under Bolshevik auspices. Yet twenty-seven of the thirty-six million votes went to other parties. A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party.

The Constituent Assembly opened on 18th January, 1918. "The Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries occupied the extreme left of the house; next to them sat the crowded Socialist Revolutionary majority, then the Mensheviks. The benches on the right were empty. A number of Cadet deputies had already been arrested; the rest stayed away. The entire Assembly was Socialist - but the Bolsheviks were only a minority."

When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. The following day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. "In all Parliaments there are two elements: exploiters and exploited; the former always manage to maintain class privileges by manoeuvres and compromise. Therefore the Constituent Assembly represents a stage of class coalition.

In the next stage of political consciousness the exploited class realises that only a class institution and not general national institutions can break the power of the exploiters. The Soviet, therefore, represents a higher form of political development than the Constituent Assembly."

Soon afterwards all opposition political groups, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and the Constitutional Democratic Party, were banned in Russia. Maxim Gorky, a world famous Russian writer and active revolutionary, pointed out: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished and tens of thousands of workers and peasants... The unarmed revolutionary democracy of Petersburg - workers, officials - were peacefully demonstrating in favour of the Constituent Assembly. Pravda lies when it writes that the demonstration was organized by the bourgeoisie and by the bankers.... Pravda knows that the workers of the Obukhavo, Patronnyi and other factories were taking part in the demonstrations. And these workers were fired upon. And Pravda may lie as much as it wants, but it cannot hide the shameful facts."

Rosa Luxemburg agreed with Gorky about the closing down of the Constituent Assembly. In her book, Russian Revolution, written in 1918 but not published until 1922, she wrote: "We have always exposed the bitter kernel of social inequality and lack of freedom under the sweet shell of formal equality and freedom - not in order to reject the latter, but to spur the working-class not to be satisfied with the shell, but rather to conquer political power and fill it with a new social content. It is the historic task of the proletariat, once it has attained power, to create socialist democracy in place of bourgeois democracy, not to do away with democracy altogether."

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, went to interview Luxemburg while she was in prison in Germany. He later reported: "She asked me if the Soviets were working entirely satisfactorily. I replied, with some surprise, that of course they were. She looked at me for a moment, and I remember an indication of slight doubt on her face, but she said nothing more. Then we talked about something else and soon after that I left. Though at the moment when she asked me that question I was a little taken aback, I soon forgot about it. I was still so dedicated to the Russian Revolution, which I had been defending against the Western Allies' war of intervention, that I had had no time for anything else."

As Paul Frölich pointed out: "She (Rosa Luxemburg) was unwilling to see criticism suppressed, even hostile criticism. She regarded unrestricted criticism as the only means of preventing the ossification of the state apparatus into a downright bureaucracy. Permanent public control, and freedom of the press and of assembly were therefore necessary." Luxemburg argued: "Freedom for supporters of the government only, for members of one party only - no matter how numerous they might be - is no freedom at all. Freedom is always freedom for those who think differently."

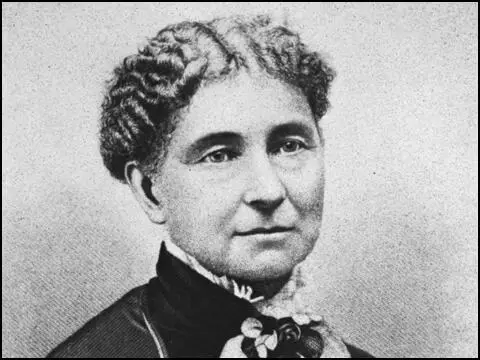

On this day in 1818 Amelia Jenks was born in Homer, New York. She only received two years of formal schooling and at the age of 22 married the lawyer Dexter Bloomer. He was a Quaker with progressive views and encouraged Amelia to write for his newspaper, the Seneca Falls County Courier. Over the next few years she wrote articles in favour for prohibition and women's rights.

In 1848 Bloomer attended the Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls but she did not sign the Declaration of Sentiments. Over the next few years she met Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

With the encouragement of her feminist friends, Amelia Bloomer started her own bi-weekly newspaper, The Lily. Bloomer used the journal to promote the causes of woman's suffrage, temperance, marriage law reform and higher education for women.

The Lily was a great success and quickly built a circulation of over 4,000. In 1851 Bloomer began to publish articles concerning women's clothing. Female fashion at the time consisted of tightly laced corsets, layers of petticoats and floor-length dresses. Bloomer began to advocate the wearing of clothes that had first been worn by Fanny Wright and the women living in the socialist commune, New Harmony in the 1820s. This included loose bodices, ankle-length pantaloons and a dress cut to above the knee.

Bloomer and other campaigners for women's rights such as Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton began wearing these clothes. Most feminists abandoned this type of clothing as they concluded that the ridicule it frequently elicited undermined attempts to convince people of the need for social reform. However, Bloomer, continued to wear these clothes until the late 1850s.

The Lily ceased publication after Bloomer moved to Council Buffs, Iowa in 1855. She continued to play an active role in the campaign for women's rights and as well as speaking at public meetings was president of the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association (1871-73).

Amelia Bloomer died at Council Buffs on 30th December, 1894.

On this day in 1819 feminist writer Julia Ward, the daughter of a wealthy banker, was born. She developed radical political opinions and was active in the American Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1843 Julia married Samuel Gridley Howe, a fellow campaigner against slavery. The couple were both members of the Free-Soil Party and between 1851 and 1853 Julia and her husband edited the anti-slavery journal Commonwealth.

Julia Ward Howe also published several volumes of poetry including Passion Flowers (1854) and Words for the Hour (1857). In 1862 the Atlantic Monthly published her Battle Hymn of the Republic.

In 1868 Howe founded the New England Women's Suffrage Association. The following year Howe and Lucy Stone formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Between 1870 and 1890 Howe and Stone edited the organization's magazine, the Woman's Journal.

Julia Ward Howe, who in 1898 became the first woman to be elected to the American Academy of Arts, died in 1910.

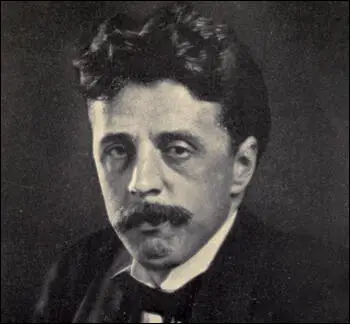

On this day in 1867 Arnold Bennett, the son of a solicitor, was born in Hanley, Staffordshire. Educated locally and at London University, he became a solicitor's clerk, but later transferred to journalism, and in 1893 became assistant editor of the journal Woman.

Bennett published his first novel The Man from the North in 1898. This was followed by Anna of the Five Towns (1902), The Old Wives' Tale (1908), Clayhanger (1910), The Card (1911) and Hilda Lessways (1911).

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Charles Mastermanthe head of the War Propaganda Bureau (WPB) invited twenty-five leading British authors to Wellington House, to discuss ways of best promoting Britain's interests during the war. Those who attended the meeting included Bennett, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

Bennett soon became one of the most important figures in this secret organisation. His first contribution to the propaganda effort was Liberty: A Statement of the British Case. It first appeared as an article in the Saturday Evening Post. In December it was expanded and published as a pamphlet by the War Propaganda Bureau. To disguise the fact it was a government publication, the WPB used the Hodder and Stoughton imprint.

When George Bernard Shaw, who was unaware of the existence of the War Propaganda Bureau, attacked what he believed to be jingoistic articles and poems being produced by British writers during the war, Bennett was the one chosen to defend their actions in the press.

In June, 1915, the WPB arranged for Bennett to tour the Western Front. Bennett was deeply shocked by the conditions in the trenches and was physically ill for several weeks afterwards. His friend, Frank Swinnerton, later recalled, "he visited the front as a duty, and was horrified at what he saw and felt that he must not express that horror." Bennett agreed to provide an account of the war that would encourage men to join the British Army. The result was the pamphlet, Over There: War Scenes on the Western Front (1915).

In March, 1918, Lord Beaverbrook, the new Minister of Information, recruited Bennett and Charles Masterman to join his new three-man British War Memorial Committee (BWMC). Their job was to select artists to produce paintings that would help the war effort. Bennett was also appointed director of British propaganda in France.

After the war Bennett returned to writing novels such as Riceyman Steps (1923) and Imperial Palace (1930). Bennett also became a director of the New Statesman. Arnold Bennett died on 27th March 1931.

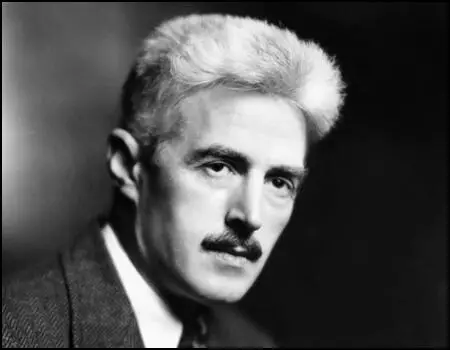

On this day in 1894 Dashiell Hammett, the son of a clerk, was born in St. Mary's County, Maryland. He left school at 13 and was employed in a variety of different jobs before joining the Pinkerton Detective Agency in 1915.

Lillian Hellman later claimed that Hammett turned down an offer of $5,000 to "do away with" Frank Little while working in Montana. Little, a leading figure in the Industrial Workers of the World was lynched in August 1917. Hellman recalled: "Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer (to kill Frank Little) so many times, that I came to believe, knowing him now, that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would murder, and the fact that Frank Little was lynched with three other men in what was known as the Everett Massacre must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I think I can date Hammett's belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little's murder."

Disgusted by the behaviour of the Pinkerton agents, Hammett joined the United States Army during the First World War. However, he contracted tuberculosis and spent some time in army hospitals. While in hospital Hammett met and married a nurse, Josephine Dolan. The couple had two daughters, Mary Jane (1921) and Josephine (1926). However, the couple eventually parted abut Hammett continued to financially support his wife and daughters. In 1929 he began an affair with Nell Martin, the author of several stories that had been made into movies. This included The Adventures of Mazie (1925), The Vanishing Armenian (1925), High, But Not Handsome (1926) and Little Andy Looney (1926).

Hammett's work with the Pinkerton Detective Agency provided material for detective stories that he published in the Black Mask Magazine. His first novel, Red Harvest, appeared in 1929. This was followed by The Dain Curse (1929) and The Maltese Falcon (1930), a novel that introduced the fictional detective, Sam Spade. After the publication of The Glass Key (1931) and The Thin Man (1932), Hammett was invited to Hollywood where he worked on several scripts.

During this period he began living with Lillian Hellman and over the next few years the couple became involved in the campaign against the growth of fascism in Europe. They joined with other literary figures such as Clifford Odets, Michael Gold, John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway in supporting the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. In 1937 he joined the American Communist Party.

On 26th May, 1938, the United States House of Representatives authorized the formation of the Special House Committee on Un-American Activities. The first chairman of the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was Martin Dies. The original intention of the HUCA was to investigate both left-wing and right wing political groups. In a statement made on 20th July 1938, Dies claimed that many Nazis and Communists were leaving the United States because of his pending interrogations. The New Republic argued that the right-wing Dies, who it described as "physically a giant, very young, ambitious, and cocksure" would target those on the left. It was no surprise when Dies immediately announced that he intended to investigate aspects of the New Deal that had been established by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

J. Parnell Thomas, a member of the HUCA, described the Federal Theatre Project as being "infested by radicals from top to bottom" and on 26th July, 1938, called for Hallie Flanagan to answer questions before the committee. Flanagan immediately went on the attack arguing that: "Some of the statements reported to have been made by him (Parnell Thomas) are obviously absurd... of course no one need first join or be a member of any organization in order to obtain employment in a theatre project."

Hammett was one of those who came to the defence of Flanagan. In October 1938 he argued: "We indignantly reject these irresponsible attacks. At this crucial time when the cooperation of all democratic forces is so essential, this attack throws a very dubious light on the character of the whole Dies investigation. It emphasizes the need for the greatest alertness on the part of all democracy-loving American people."

Hammett was involved in the screenplay for Woman in the Dark (1934), Mister Dynamite (1935), The Glass Key (1935), Satan Met a Lady (1936), After the Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), Shadow of the Thin Man (1941) and The Maltese Falcon (1941).

In 1942, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hammett enlisted in the United States Army. As a victim of tuberculosis he was not fit enough for active service and so he was sent to the Aleutian Islands, where he edited an army newspaper, which people complained was too pro-Russian.

After the Second World War Hammett decided to concentrate on politics rather than writing. On 5th June 1946 he was elected President of the Civil Rights Congress. Later that year a bail fund was created by the CRC to help those arrested for political reasons. The three trustees of the fund were Hammett, Robert W. Dunn, and Frederick Vanderbilt Field.

On 20th July, 1948, Eugene Dennis, the general secretary of the American Communist Party, and eleven other party leaders, including William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government". The CRC fund was used to bail thses men.

Dashiell Hammett testified on July 9, 1951 in front of Judge Sylvester Ryan. During the hearing Hammett refused to provide the list of contributors to the bail fund. On every question regarding the CRC or the bail fund, Hammett took the Fifth Amendment. Hammett was then called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Hammett agreed to talk about his own involvement with radical groups, but was unwilling to give names of his comrades. He was found guilty of contempt of Congress and as well as being blacklisted, was sent to prison for six months.

Dashiell Hammett died in New York City on 10th January, 1961.

On this day in 1954 James Eastland makes speech in the Senate in favour of Jim Crow laws.

The southern institution of racial segregation or racial separation was the correct, self-evident truth which arose from the chaos and confusion of the reconstruction period. Separation promotes racial harmony. It permits each race to follow its own pursuits, and its own civilization. Segregation is not discrimination. Segregation is not a badge of racial inferiority, and that it is not is recognized by both races in the Southern States. In fact, segregation is desired and supported by the vast majority of the members of both races in the South, who dwell side by side under harmonious conditions.

The negro has made a great contribution to the South. We take pride in the constant advance he has made. It is where social questions are involved that Southern people draw the line. It is these social institutions with which Southern people, in my judgment, will not permit the Supreme Court to tamper.

Let me make this clear, Mr. President: There is no racial hatred in the South. The Negro race is not an oppressed race. A great Senator from the State of Idaho, Senator William E. Borah, a few years ago said on the floor of the Senate: "Let us admit that the South is dealing with this question as best it can, admit that the men and women of the South are just as patriotic as we are, just as devoted to the principles of the Constitution as we are, just as willing to sacrifice for the success of their communities as we are. Let us give them credit as American citizens, and cooperate with them, sympathize with them, and help them in the solution of their problem, instead of condemning them. We are one people, one nation, and they are entitled to be treated upon this basis."

Mr. President, it is the law of nature, it is the law of God, that every race has both the right and the duty to perpetuate itself. All free men have the right to associate exclusively with members of their own race, free from governmental interference, if they so desire. Free men have the right to send their children to schools of their own choosing, free from governmental interference and to build up their own culture, free from governmental interference. These rights are inherent in the Constitution of the United States and in the American system of government, both state and national, to promote and protect this right.

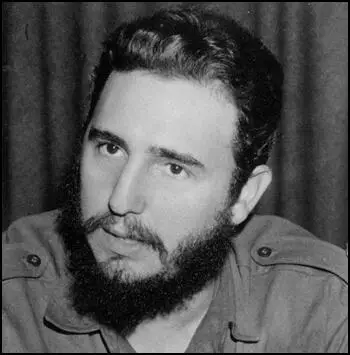

On this day in 1967 a CIA secret memo by J. S. Earman admits that Jake Esterline was involved in plots to assassinate Fidel Castro.

We find evidence of at least three, and perhaps four, schemes that were under consideration well before the Bay of Pigs, but we can fix the time frame only speculatively. Those who have some knowledge of the episodes guessed at dates ranging from 1959 through 1961. The March-to-August span we have fixed may be too narrow, but it best fits the limited evidence we have.

a. None of those we interviewed who was first assigned to the Cuba task force after the Bay of Pigs knows of any of these schemes.

b. J.D. (Jake) Esterline, who was head of the Cuba task force in pre-Bay of Pigs days, is probably the most reliable witness on general timing. He may not have been privy to the precise details of any of the plans, but he seems at least to have known of all of them. He is no longer able to keep the details of one plan separate from those of another, but each of the facts he recalls fits somewhere into one of the schemes. Hence, we conclude that all of these schemes were under consideration while Esterline had direct responsibility for Cuba operations.

c. Esterline himself furnishes the best clue as to the possible time span. He thinks it unlikely that any planning of this sort would have progressed to the point of consideration of means until after U.S. policy concerning Cuba was decided upon about March 1960. By about the end of the third quarter of 1960, the total energies of the task force were concentrated on the main-thrust effort, and there would have been no interest in nor time for pursuing such wills-o'-the-wisp as these.

We are unable to establish even a tentative sequence among the schemes; they may, in fact, have been under consideration simultaneously. We find no evidence that any of these schemes was approved at any level higher than division, if that. We think it most likely that no higher-level approvals were sought, because none of the schemes progressed to the point where approval to launch would have been needed.

xx