On this day on 23rd July

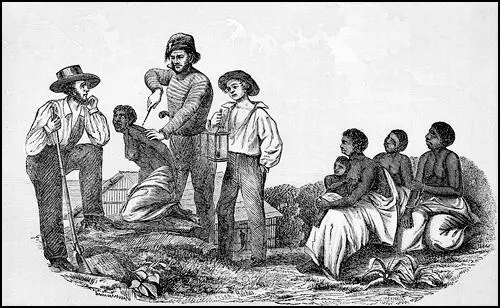

On this day in 1836 advert in Mississippi Gazette mentions the branding of slaves. "A negro man who says his name is Josiah, that he belongs to Mr. John Martin, living in Louisiana, twenty miles below Nathchez. Josiah is five feet eight inches high, heavy built, copper colour; his back very much scarred with the whip, and branded on the thigh and hips in three or four places thus: "J.M." The rim of his right ear has been bitten or cut off. He is about 31 years of age. Had on, when committed, pantaloons, made of bed-ticking, cotton coat, and an old fur hat very much worn. The owner of the above described negro is requested to comply requisitions of law, in such, cases made and provided for."

The law provided slaves with virtually no protection from their masters. On large plantations this power was delegated to overseers. These men were under considerable pressure from the plantation owners to maximize profits. They did this by bullying the slaves into increasing productivity. The punishments used against slaves judged to be under-performing included the use of the whip. Sometimes slave-owners resorted to mutilating and branding their slaves.

An advertisement was published in The North Carolina Standard on 28th July, 1838: "Twenty dollars reward. Runaway from the subscriber, a negro woman and two children; the woman is tall and black, and a few days before she went off burnt her on the left side of her face with the letter M." Another newspaper reported that a wealthy man from St. Louis had branded his slave Reuben with the words; "A slave for life."

On this day in 1885 Ulysses S. Grant, 18th President of the United States, died. In 1868 the Republican Party nominated Grant for president. His running mate was Schuyler Colfax, a man associated with the Radical Republican. Grant and Colfax won 26 states out of 34. Three states, Virginia, Mississippi and Texas, had no vote as they had not been yet admitted to the Union. However, Grant only won 52.7 per cent of the popular vote and only narrowly beat his Democratic opponent, Horatio Seymour.

At 46, Grant was the youngest man to be elected president. His first administration included Elihu Washburne (secretary of State), George Boutwell (Secretary of the Treasury), William T. Sherman (Secretary of War), John Creswell (Postmaster General) and Ebenezer Hoar (Attorney General). Later additions included Hamilton Fish (Secretary of State), George H. Williams (Attorney General), William Belknap (Secretary of War) and Zachariah Chandler (Secretary of the Interior).

Politically inexperienced, he had problems dealing with Congress. However, he was popular with the people of America and in 1872 easily defeated his opponent, Horace Greeley. Grant's second term was plagued by corruption and scandal. He announced that he intended to "Let no man escape" but he was criticized for the way he dealt with the situation when Orville Babcock, his private secretary, and William Belknap, his Secretary of War, were accused of corruption. Although loyally defended by his friend, Thomas Nast, the political cartoonist, the "maker of presidents", these events severely damaged his reputation. When Grant's period of office came to an end in 1877, he announced to the American people, "Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent."

In 1881 Grant and his son became involved in the investment firm of Grant & Ward. Grant encouraged others to invest in this company and his reputation was again damaged when the firm collapsed and it was discovered that his partner, Ferdinand Ward, was guilty of corruption. With the support of his friend, Mark Twain, Grant began work on his memoirs. Suffering from throat cancer, Grant completed his autobiography, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, shortly before his death on 23rd July, 1885.

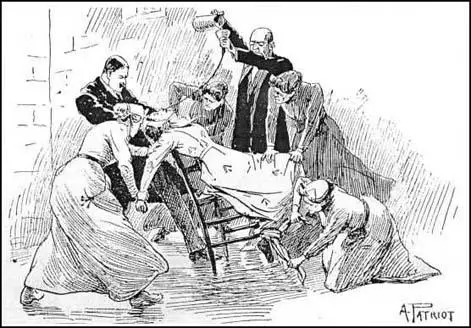

On this day in 1909 Christabel Pankhurst advocate the hunger-strike as a WSPU tactic, newspaper, Votes for Women, "The spiritual force which they are exerting is so great that prison walls are rent, prison gates forced open, and they emerge free in body as they have never for an instant ceased to be... Those who, in these latter days, are privileged to witness this triumph of the spiritual over the physical, understand the true meaning and manner of the miracles of old times."

Christabel was also responsible for persuading 116 doctors to sign a letter sent to Henry Asquith, the new prime minister, protesting against artificial feeding. "We submit to you, that this method of feeding when the patient resists is attending with the gravest risks, that unforeseen accidents are liable to occur, and that the subsequent health of the person may be seriously injured. In our opinion this action is unwise and inhumane. We therefore beg that you will interfere to prevent the continuance of this practice."

On 8th October, 1909, Christabel had a meeting with leading militants, Constance Lytton, Jane Brailsford, Emily Wilding Davison, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney and Kitty Marion. who resolved to undertake acts of violence in order to protest against forcible feeding. "There were twelve women... all intending stone-throwers, and Christabel was there to hearten us up and go into details about the way in which we were to do it."

The women sent a letter to The Times explaining what they intended to do: "We want to make it known that we shall carry on our protest in our prison cells. We shall put before the Government by means of the hunger-strike four alternatives: to release us in a few days; to inflict violence upon our bodies; to add death to the champions of our cause by leaving us to starve; or, and this is the best and only wise alternative, to give women the vote. We appeal to the Government to yield, not to the violence of our protest, but to the reasonableness of our demand, and togrant the vote to the duly qualified women of the country. We shall then serve our full sentence quietly and obediently and without complaint. Our protest is against the action of the Government in opposing woman suffrage, and against that alone. We have no quarrel with those who may be ordered to maltreat us".

On this day in 1913, hooligans make violet attack on women's suffrage meeting in East Grinstead. The meeting was organised by Marie Corbett of the East Grinstead Suffrage Society and Edward Steer of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage at East Grinstead. As the The East Grinstead Observer reported: "The procession was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead. The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them."

Edward Steer was the chairman and Laurence Housman was the main speaker. The local newspaper reported that both men were attacked by the crowd: "By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment."

On this day in 1980 anarchist leader, Mollie Steimer, died in her home following a heart-attack.

Mollie Steimer was born in Dunaevtsky, Russia, on 21st November, 1897. When she was fifteen her family emigrated to the United States and settled in New York City.

Steimer found work in a garment factory and soon became involved in trade union activities. This led to her reading books on politics including Women and Socialism (August Bebel), Statehood and Anarchy (Mikhail Bakunin), Memoirs of a Revolutionist (Peter Kropotkin) and Anarchism and Other Essays (Emma Goldman).

In 1917 Steimer joined the Freiheit, a group of Jewish anarchists based in New York City, that had been formed by Johann Most. Steimer shared a six-room apartment at 5 East 104th Street in Harlem with members of the group. This also became the place where the Freiheit held its meetings and published its newspaper. Other members included Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Some of the younger members, including Steimer, formed a new group called Frayhayt (Freedom) and launched a new journal with the same name. She persuaded Robert Minor to produce some cartoons for the journal.

The Frayhayt group were opposed to the United States becoming involved in the First World War. On the masthead of their newspaper contained the words: "The only just war is the social revolution". After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, making it an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Steimer was furious when she heard the news that the United States Army had invaded Russia after the Bolshevik government signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. She produced two leaflets, one in English and one in Yiddish, appealing to American workers to launch a general strike. "Will you allow the Russian Revolution to be crushed? You; yes, we mean you, the people of America! The Russian Revolution calls to the workers of the world for help... Yes, friends, there is only one enemy of the workers of the world and that is capitalism."

An estimated 10,000 leaflets were distributed in New York City before Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Samuel Lipman, Jacob Schwartz and Gabriel Prober were arrested on 23rd August, 1918, for publishing material that undermined the American war effort. The men were beaten in prison and Schwartz died before he could be brought to court. At his funeral, John Reed and Alexander Berkman made speeches to a gathering of 1,200 mourners.

The trial began on 10th October, 1918, at the Federal Court House in New York City. During the proceedings, the 20 year old Steimer explained her anarchist beliefs: "Anarchism is a new social order where no group shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. Every person shall have an equal opportunity to develop himself well, both mentally and physically. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Every person shall produce as much as he can, and enjoy as much as he needs - receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards education, towards knowledge. While at present the people of the world are divided into various groups, calling themselves nations, while one nation defies another - in most cases considers the others as competitive - we, the workers of the world, shall stretch out our hands towards each other with brotherly love. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it."

Steimer was found guilty of breaking the Espionage Act and was sentenced to fifteen years and a $500 fine. Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky and Samuel Lipman got twenty years and a $1,000 fine. Gabriel Prober, who had been arrested by mistake, was cleared of all charges. Zechariah Chafee of the Harvard Law School led the protests against the severity of the sentences. He pointed out had been convicted solely for advocating non-intervention in the affairs of another nation: "After priding ourselves for over a century on being an asylum for the oppressed of all nations, we ought not suddenly jump to the position that we are only an asylum for men who are no more radical than ourselves."

Others who joined in the protests included Felix Frankfurter, Norman Thomas, Roger Baldwin, Margaret Sanger, Lincoln Steffens, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Hutchins Hapgood, Leonard Dalton Abbott, Alice Stone Blackwell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Neith Boyce. A group, the League of Amnesty of Political Prisoners was formed and it published a leaflet on the case, Is Opinion a Crime? Steimer and the the other three anarchists were released on bail to await the results of their appeal.

Over the next few months Steimer was arrested seven times but after being held in various prisons was always released without charge. Agnes Smedley was one of those who met her in prison: "Mollie Steimer championed the cause of the prisoners - the one with venereal disease, the mother with diseased babies, the prostitute, the feeble-minded, the burglar, the murderer. To her they were but products of a diseased social system. She did not complain that even the most vicious of them were sentenced to no more than 5 or 7 years, while she herself was facing 15 years in prison."

Emma Goldman complained that: "The entire machinery of the United States government was being employed to crush this slip of a girl weighing less than eighty pounds." On the 30th October, 1919, she was arrested she was taken to Blackwell Island. While in prison the Supreme Court upheld her conviction under the Espionage Act. However, two justices, Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, issued a strong dissenting opinion. Steimer was now transferred to the Jefferson City Prison in Missouri.

During this period A. Mitchell Palmer, the attorney general and his special assistant, John Edgar Hoover, used the Sedition Act to launch a campaign against radicals and their organizations. Using this legislation it was decided to remove immigrants who had been involved in left-wing politics. This included Steimer, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and 245 other people who were deported to Russia. A fellow anarchist, Marcus Graham, wrote: "In Russia their activity is yet more needed. For there, a government rules masquerading under the name of the proletariat and doing everything imaginable to enslave the proletariat."

Deported to Russia on the Estonia, Steimer arrived in Moscow on 15th December, 1921. Over the next few months she worked closely with Vsevolod Volin, the editor of the Golos Truda, a journal published in Petrograd. She was also a member of the the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations. The Bolshevik government hated anarchists and she soon became a target for the Russian Secret Police.

On 1st November, 1922 she was arrested with her boyfriend, Senya Fleshin and charged with aiding criminal elements in Russia. Sentenced to two years in Siberia, Steimer managed to escape and return to Moscow where she worked for the Society to Help Anarchist Prisoners. She was soon arrested and on 27th September she was deported to Germany where she joined Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman in Berlin.

Mollie Steimer began contributing articles for anarchist journals in Europe. In one article published in January 1924 she argued that in Russia, a great popular revolution had been usurped by a ruthless political elite: "No, I am not happy to be out of Russia. I would rather be there helping the workers combat the tyrannical deeds of the hypo-critical Communists."

Steimer and Senya Fleshin moved to Paris and joined a group of anarchist exiles that included Nestor Makhno, Peter Arshinov, Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Sébastien Faure, Jacques Doubinsky and Rudolf Rocker. They formed the Joint Committee for the Defense of Revolutionaries Imprisoned in Russia. In 1926 they established the Relief Fund of the International Working Men's Association for Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalists Imprisoned in Russia.

Emma Goldman sometimes clashed with Steimer: "Mollie Steimer is a fanatic to the highest degree... She is terribly sectarian, set in her notions, and has an iron will. No ten horses could drag her from anything she is for or against. But with it all she is one of the most genuinely devoted souls living with the fire of our ideal."

In 1926 Nestor Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Steimer, Senya Fleshin, Emma Goldman, Vsevolod Volin, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation. In November 1927 Steimer wrote: "The entire spirit of the platform is penetrated with the idea that the masses must be politically led during the revolution. There is where the evil starts."

Senya Fleshin took up photography. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "In order to earn a living, Senya had meanwhile taken up the profession of photography, for which he exhibited a remarkable talent; he became the Nadar of the anarchist movement, with his portraits of Berkman, Volin, and many other comrades, both well known and obscure, as well as a widely reproduced collage of the international anarchist press."

In 1929 Fleshin was invited to work in the studio of Sasha Stone in Berlin. Steimer went with him and they remained there until Adolf Hitler took power. They no longer felt safe in Nazi Germany and they moved back to Paris, where they remained until the Second World War. After the Nazi invasion and the formation of the Vichy government, Steimer and Fleshin decided to go to Mexico. They attempted to persuade Vsevolod Volin to go with them but he refused, claiming he had to stay in France in order to "prepare for the revolution when the war is over."

In Mexico City Steimer and Fleshin operated a successful photographic studio. They retired to Cuernavaca in 1963. As the of Anarchist Portraits (1995) has pointed out: "Fluent in Russian, Yiddish, English, German, French, and Spanish, she corresponded with comrades and kept up with the anarchist press around the world."