On this day on 22nd March

On this day in 1599 Anthony van Dyck is born in Antwerp. After studying painting under Hendrick van Balen he was accepted as a master of the guild of St Luke at Antwerp.

Van Dyke visited England in 1620 where he painted a full-length portrait of James I at Windsor. He also painted the wife of Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel. He returned to Europe and painted all the leading figures including the Prince of Orange.

In 1632 Van Dyke arrived back in England and Charles I appointed him as his Principal Painter. As well as the king he painted Henrietta Maria and her two children. He also painted William Laud, Earl of Denbigh, Earl of Pembroke, Thomas Wentworth, Algernon Percy and Prince Rupert.

Sir Anthony Van Dyke died in 1641 and was replaced as Principal Painter by William Dobson.

On this day in 1641 Thomas Wentworth's trial for treason began. William Laud upset the Presbyterians in Scotland when he insisted they had to use the English Prayer Book. Scottish Presbyterians were furious and made it clear they were willing to fight to protect their religion. In 1639 the Scottish army marched on England. Charles, unable to raise a strong army, was forced to agree not to interfere with religion in Scotland. The Scots demanded £40,000 a month in compensation. If this was not paid they would leave their army in England. After lengthy negotiations, this was reduced to £850 a day.

Charles I did not have the money to pay the Scots and so he had to ask Parliament for help. The Parliament summoned in 1640 lasted for twenty years and is therefore usually known as The Long Parliament. This time Parliament was determined to restrict the powers of the king. The king's two senior advisers, William Laud and Thomas Wentworth were arrested and sent to the Tower of London.

Charged with treason, Wentworth's trial opened on 22nd March, 1641. The case could not be proved and so his enemies in the House of Commons, led by John Pym, Arthur Haselrig and Henry Vane, resorted to a Bill of Attainder. Charles gave his consent to the Bill of Attainder and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, was executed on 12th May 1641. "Nothing left so deep a scar on Charles's character, and his subsequent reputation, as the death of Stafford."

On this day in 1638 Anne Hutchinson is expelled from Massachusetts Bay Colony for religious dissent. Anne Hutchinson, the daughter of a clergyman, was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1615. A Puritan, Hutchinson emigrated with her husband to America in 1634.

Hutchinson settled in Massachusetts Bay, where she soon obtained a following as a preacher. Hutchinson began to claim that good conduct could be a sign of salvation and affirmed that the Holy Spirit in the hearts of true believers relieved them of responsibility to obey the laws of God. She also criticised New England ministers for deluding their congregations into the false assumption that good deeds would get them into heaven.

Complaints were made about Hutchinson's teachings and John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts, called her to appear before the authorities. During her cross-examination she claimed that she had received a revelation from God. To the Puritan authorities this was blasphemy and she was banished from the community.

Hutchinson joined Roger Williams and his colony on Rhode Island. The colony was a haven of religious toleration and admitted Jews and Quakers and other religious dissenters.

After the death of her husband in 1642, Hutchinson moved to a new settlement in Pelham Bay. The following year Anne Hutchinson and fourteen members of her family were murdered by Native Americans in the area.

On this day in 1808 Caroline Sheridan, the daughter of Thomas Sheridan, colonial official, and his wife, Caroline Henrietta Callender Sheridan, was born. Her grandfather was Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright and politician. Caroline's father died when she was eight years old, leaving the family in serious financial problems.

For a while Caroline lived with her uncle, the writer, Charles Sheridan. At an early age she developed literary ambitions. She spent time with her uncle and at the age of eleven she wrote: "I invariably left his study with an enthusiastic determination to write a long poem of my own."

Caroline was considered to be a high spirited and rather uncontrollable. "She even looked strange when she was young, with huge dark eyes and a great mass of wild black hair. Her habit of lowering her head and looking at people through her thick black eyelashes was thought of as furtive. People were not comfortable with her nor she with them. In spite of her quick tongue she was actually quite shy."

In 1824, finding her sixteen-year-old daughter too difficult to manage, Mrs Sheridan sent her to a boarding-school at Shalford. The girls at the school were invited to Wonersh Park, the seat of the local landowner, William Norton (Lord Grantley). Caroline was seen by Grantley's younger brother, George Norton, and informed her governess of his intention to propose marriage to her. Norton put his proposal into writing and Caroline's mother accepted his offer but insisted that he waited three years.

Diane Atkinson, the author of The Criminal Conversation of Mrs Norton (2013) has argued that might have been a good reason why Caroline's mother had suggested that Norton should not marry her daughter straight away: "Caroline was horrified at the prospect of marrying a man she barely remembered seeing, but it was her mother's right and duty to secure a husband for her and there had been no other interest. Perhaps Mrs Sheridan was playing for time, hoping someone else would come along."

Mary Shelley, who knew her well, later recalled that she could understand why Norton wanted to marry her: "I never saw a woman I thought so fascinating. Had I been a man I should certainly have fallen in love with her... I would have been spellbound, and had she taken the trouble, she might have wound me round her finger. There is something in the pretty way in which her witticisms glide, as it were, from her lips, that is charming."

Although she did not love Norton, Caroline agreed to help her mother's financial situation by marrying him. The other reason she married Norton was the fear that she would never receive another offer: "The only misfortune I ever particularly dreaded was living and dying a lonely old maid... An old maid is never anyone's first object therefore I object to that situation."

The marriage took place in 1827 when Caroline was nineteen. The marriage was a disaster from the outset, mainly because they were completely incompatible. "George Norton was slow, rather dull, jealous, and obstinate; Caroline was quick-witted, vivacious, flirtatious, and egotistical." They also disagreed passionately about politics. Norton was a hard-line Tory MP, whereas Caroline had developed liberal opinions.

Caroline Norton later recalled: "We had been married about two months, when, one evening, after we had all withdrawn to our apartments, we were discussing some opinion Mr. Norton had expressed; I said, that I thought I had never heard so silly or ridiculous a conclusion. This remark was punished by a sudden and violent kick; the blow reached my side; it caused great pain for several days, and being afraid to remain with him, I sat up the whole night in another apartment."

This violent behaviour continued: "Four or five months afterwards, when we were settled in London, we had returned home from a ball; I had then no personal dispute with Mr. Norton, but he indulged in bitter and coarse remarks respecting a young relative of mine, who, though married, continued to dance - a practice, Mr. Norton said, no husband ought to permit. I defended the lady spoken of when he suddenly sprang from the bed, seized me by the nape of the neck, and dashed me down on the floor. The sound of my fall woke my sister and brother-in-law, who slept in a room below, and they ran up to the door. Mr. Norton locked it, and stood over me, declaring no one should enter. I could not speak - I only moaned. My brother-in-law burst the door open and carried me downstairs. I had a swelling on my head for many days afterwards."

Caroline had three children, Fletcher (1829), Brinsley (1831) and William (1833). The couple constantly argued about politics. They disagreed intensely on virtually all the main political issues of the day. Caroline, like her grandfather, was a Whig who favoured extensive social reform. George Norton was the Tory MP from Guildford, who had opposed measures favoured by Caroline such as Catholic Emancipation and Parliamentary Reform.

Caroline Norton had always been interested in writing and in 1829 her long poem The Sorrows of Rosalie was published. This was followed by The Undying One in 1830. As a result of these poems, Caroline was invited to become editor of La Belle Assemblee and Court Magazine. Her close friends during this period included Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Mary Shelley, Fanny Kemble, Benjamin Disraeli, Edward Trelawney and Samuel Rogers.

In the 1830 General Election, George Norton lost his seat in the House of Commons. His brother, William Norton, argued that the main reason for this was that he had not been around enough for the voters to see him. Caroline Norton wrote to her sister, suggesting that he was unlucky to be defeated: "He assures me that although thrown out he was the popular candidate... that all those who voted against him did it with tears."

Earl Grey, the leader of the Whigs, became Prime Minister. Norton asked his wife if she could use her contacts with the new administration to obtain for him a well-paid government post. In 1831 Caroline met William Lamb, Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary, and he arranged for George Norton to be appointed as a magistrate in the Lambeth Division of the Metropolitan Police Courts, with the generous salary of £1,000 a year.

Lord Melbourne and Caroline Norton became close friends. Melbourne, a widower, had a reputation as a womanizer, and rumours began to circulate about his relationship with Caroline. Melbourne's biographer, Peter Mandler, has pointed out that the relationship "achieved a happiness that had escaped him earlier... it is less likely to have been sexual, but it provided Melbourne with the same emotional reassurance, while allowing him to play mild games of hot-and-cold flirtation and discipline".

Friends pointed out that in her twenties "the dark wildness of her younger days had been replaced by a confidence and control observers found remarkable". Her intellectual abilities also impressed people who met her: "She was bold in her opinions and brilliant in her arguments and never held back from either." Charles Sumner, commented that Caroline Norton combined "the grace and ease of a woman with a strength and skill of which any man might be proud."

George Norton heard rumours about the relationship but did not intervene as he hoped he would benefit from Caroline's friendship with the Home Secretary. Claire Tomalin has argued: "Lord Melbourne was nearly thirty years her senior; his wife (Caroline Lamb) had lately died; and he was a man peculiarly susceptible to the delights of a quasi-paternal relationship. Caroline Norton offered him beauty, charm, a sharp interest in everything that interested him and something like an eighteenth-century sense of fun; more, she idealized him for his urbanity, his power, wealth and well-preserved good looks."

George Norton continued to beat Caroline and after one row in the summer of 1833 she locked herself in the drawing-room. This infuriated George who hurled himself at the door like a battering ram until it not only caved in but the whole framework of the door came away from the wall. Although she was seven months pregnant he "manhandled her down the stairs, punching and slapping her". Eventually, the servants were forced to restrain him.

In 1835 Norton took the opportunity when his wife was visiting her sister to take their three children out of the house, and put them under the charge of a cousin, Miss Vaughan, who refused to let their mother have access to them. Caroline took refuge with her own family, and then found out the dreadful position in which the law placed her. She had nor rights concerning her children, and might never see them again until they were of age, without permission from her husband.

Caroline Norton pointed out that even the money she earned as a writer belonged to her husband: "An English wife cannot legally claim her own earnings. Whether wages for manual labour, or payment for intellectual exertion, whether she weed potatoes, or keep a school, her salary is the husband's; and he could compel a second payment, and treat the first as void, if paid to the wife without his sanction." However, Caroline Norton was no feminist. She pointed out that "The natural position of woman is inferiority to man… I never pretended to the wild and ridiculous doctrine of equality".

Lord Melbourne became prime minister in March, 1835. Norton, who had serious financial problems, told Caroline that he intended to sue Lord Melbourne for adultery. Norton then approached Melbourne and suggested that he should be paid £1,400 to avoid a politically damaging court case. Melbourne, who denied that he had been having a sexual relationship with Caroline, refused to give Norton any money.

George Norton now approached the Tory peer, William Best, 1st Lord Wynford, about the matter. Wynford believed that a sexual scandal involving Melbourne would bring the Whig government down and advised Norton to bring a suit charging the prime minister with "alienating his wife's affections". Norton now began to leak stories to the Tory press. Between March and June, 1835 a number of articles appeared suggesting that Melbourne was having an affair with Caroline. It was also suggested that other progressives such as Thomas Duncombe, Edward Trelawny and William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire, had also had affairs with Caroline.

Barnard Gregory, the publisher of The Satirist, took up the case. On 29th May 1836, the newspaper reported that George Norton had known for a long time of "the intimacy subsisting between his Lady and Lord Melbourne". Another newspaper, included not only Caroline but her sisters in all the innuendo and speculated openly about their reputations, mentioning in the process every gentleman who had ever been seen with them."

George Norton told Caroline that he intended to go to court over the issue. When she informed Lord Melbourne of the bad news he claimed that this was the end of his political career. She said that she would never forget "the shrinking from me and my burdensome and embarrassing distress".

Lord Melbourne offered his resignation but William IV refused to accept it. However, he was advised to break off all contact with Caroline Norton. When it became known that Lord Wynford was responsible for Norton's action against Melbourne, even some Tory newspapers defended Melbourne. One Tory was quoted as saying that the case brought "disgrace to our party".

In June 1836 Norton brought a case for criminal conversation between Melbourne and his wife to the courts, suing Melbourne for £10,000 in damages for adultery. The case began on 22nd June 1836. Two of George Norton's servants gave evidence that they believed Caroline and Lord Melbourne had been having an affair. She had been prepared for lies but what appalled her was "the loathsome coarseness and invention of circumstances which made me a shameless wretch." One maid testified that she had been "painting her face and sinning with various gentlemen" in the same week that she gave birth to her third child.

Three letters written by Melbourne to Caroline were presented in court. The contents of the three letters were very brief: (i) "I will call about half past four". (ii) "How are you? I shall not be able to come today. I shall tomorrow." (iii) "No house today. I will call after the levee. If you wish it later let me know. I will then explain about going to Vauxhall." Sir W. Follett, George Norton's counsel, argued that these letters showed "a great and unwarrantable degree of affection, because they did not begin and end with the words My dear Mrs. Norton."

One pamphlet reported: "One of the servants had seen kisses pass between the parties. She had seen Mrs Norton's arm around Lord Melbourne's neck - had seen her hand upon his knee, and herself kneeling in a posture. In that room (her bedroom) Mrs Norton has been seen lying on the floor, her clothes in a position to expose her person. There are other things too which it is my faithful duty to disclose. I allude to the marks from the consequences of the intercourse between the two parties. I will show you that these marks were seen upon the linen of Mrs Norton."

The jury was unimpressed with the evidence presented in court and Follett's constant demands for the "payment of damages to his client" and Norton's witnesses were unreliable. Without calling any of the witnesses who would have proved Caroline's innocence the jury threw the case out. However, the case had destroyed Caroline's reputation and ruined and her friendship with Lord Melbourne. He refused to see her and Caroline wrote to him that it had destroyed her hope of "quietly taking my place in the past with your wife Mrs Lamb."

Despite Norton's defeat in court, he still had the power to deny Caroline access to her children. She pointed out: "After the adultery trial was over, I learnt the law as to my children - that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them - for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr. Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney. What I suffered on my children's account, none will ever know or measure. Mr. Norton held my children as hostages, he felt that while he had them, he still had power over me that nothing could control."

Caroline wrote to Lord Melbourne, who continued to refuse to see her in case it caused another political scandal: "God forgive you, for I do believe no one, young or old, ever loved another better than I loved you... I will do nothing foolish or indiscreet - depend on it - either way it is all a blank to me. I don't much care how it ends... I have always the memory of how you received me that day, and I have the conviction that I have no further power than he allows me, over my boys. You and they were my interests in life. No future can ever wipe out the past - nor renew it."

Caroline wrote a pamphlet explaining the unfairness of this entitled The Natural Claim of a Mother to the Custody of her Children as affected by the Common Law Rights of the Father (1837): Caroline argued that under the present law, a father had absolute rights and a mother no rights at all, whatever the behaviour of the husband. In fact, the law gave the husband the legal right to desert his wife and hand over his children to his mistress. For the first time in history, a woman had openly challenged this law that discriminated against women.

Caroline Norton now began a campaign to get the law changed. Sir Thomas Talfourd, the MP for Reading agreed to Caroline's request to introduce a bill into Parliament which allowed mothers, against whom adultery had not been proved, to have the custody of children under seven, with rights of access to older children. "He was driven to do this by some personal experiences of his own, for in the course of his professional career he had twice been counsel for husbands resisting the claims of their wives, and had both times won his case in accordance with law and in violation of his sense of justice."

Talfourd told Caroline about the case of Mrs Greenhill, "a young woman of irreproachable virtue". A mother of three daughters aged two to six, she found out her husband was living in adultery with another woman. She applied to the Ecclesiastical Court for a divorce. At the courts of King's Bench it was decided that she wife must not only deliver up the children, but that the husband had a right to debar the wife of all access to them. The Vice-Chancellor said that "however bad and immoral Mr Greenhill's conduct might be... the Court of Chancery had no authority to interfere with the common law right of the father, and no power to order that Mrs. Greenhill should even see her children".

Talfourd highlighted the Greenhill case in the debate that took place over his proposed legislation. The bill was passed in the House of Commons in May 1838 by 91 to 17 votes (a very small attendance in a house of 656 members). Lord Thomas Denman, who was also the judge in the Greenhill case, made a passionate speech in favour of the bill in the House of Lords. Denman argued: "In the case of King v Greenhill, which was decided in 1836 before myself and the rest of the judges of the Court of the King's Bench, I believe there was not one judge who did not feel ashamed of the state of the law, and that it was such as to render it odious in the eyes of the country."

Despite this speech the House of Lords rejected the bill by two votes. Very few members bothered to attend the debate that took place in the early hours of the morning. Caroline Norton remarked bitterly: "You cannot get Peers to sit up to three in the morning listening to the wrongs of separated wives."

Talfourd was disgusted by the vote and published this response: "Because nature and reason point out the mother as the proper guardian of her infant child, and to enable a profligate, tyrannical, or irritated husband to deny her, at his sole and uncontrolled caprice, all access to her children, seems to me contrary to justice, revolting to humanity, and destructive of those maternal and filial affections which are among the best and surest cements of society."

Caroline Norton now wrote another pamphlet, A Plain Letter to the Lord Chancellor on the Law of Custody of Infants. A copy was sent to every member of Parliament and in 1839 Talfourd tried again. The opponents of the proposed legislation spread rumours that Talfourd and Caroline "were lovers and that he had only became involved with the issue because of their sexual intimacy".

The journal, The British and Foreign Review published a long and insulting attack in which it called Caroline Norton a "she devil" and a "she beast" and "coupled her name with Mr Talfourd in a most impertinent way." Norton wanted to prepare a legal action only to discover that as a married woman, she could not sue. She later wrote: "I have learned the law respecting married women piecemeal, by suffering every one of its defects of protection".

Sir Thomas Talfourd reintroduced the bill in 1839. It was passed by the Commons and this time he received the help in the Lords from John Copley, 1st Baron Lyndhurst. "By the law of England, as it now stood, the father had an absolute right to the custody of his children, and to take them from the mother. However pure might be the conduct of the mother - however amiable, however correct in all the relations of life, the father might, if he thought proper, exclude her from all access to the children, and might do this from the most corrupt motives. He might be a man of the most profligate habits; for the purpose of extorting money, or in order to induce her to concede to his profligate conduct, he might exclude her from all access to their common children, and the course of law would afford her no redress: That was the state of the law as it at present existed. Need he state that it was a cruel law - that it was unnatural - that it was tyrannous - that it was unjust?"

The main opposition came from George Norton's friend, William Best, 1st Lord Wynford. He argued that the proposed bill went against the best interests of men: "To give the custody of the child to the father, and to allow access to it by the mother, was to injure the child for it was natural to expect that the mother would not instill into the child any respect for the husband whom she might hate or despise. The effects of such a system would be most mischevious to the child, and would prevent its being properly brought up. If the husband was a bad man, the access to the children might not do harm, but where the fault lay with the wife, or where she was of a bad disposition, she could seriously injure its future prospects.... In his belief, where the measure, as it stood, would relieve one woman, it would ruin 100 children".

Despite the protests of some politicians, the Custody of Children Act was passed in August 1839. "This act gave custody of children under seven to the mother (provided she had not been proven in court to have committed adultery) and established the right of the non-custodial parent to access to the child. The act was the first piece of legislation to undermine the patriarchal structures of English law and has subsequently been hailed as the first success of British feminism in gaining equal rights for women".

Although the law had been passed George Norton still refused to let Caroline see her children. The new law applied only in England and Wales and so he therefore sent them all to a school in Scotland, knowing that they were now out of the jurisdiction of the English Courts. Norton also paid for people to spy on Caroline in the hope that he could acquire the evidence that she was involved in an adulterous relationship.

In September 1842, eight year old William Norton was thrown from his pony while out riding with his brother. He cut his arm and although the injury was not serious, it was not treated, and he fell gravely ill with blood poisoning. Caroline was eventually sent for but by the time she arrived William was dead. It was only after this tragedy that George Norton was willing to let the two remaining children, Fletcher and Brinsley, to live with their mother.

However, there were conditions attached. Caroline was not allowed to have a relationship with another man. George Norton retained the right to take them away from her whenever he wanted. Caroline wrote that she was in "fear and trembling" that he would take the children away again. She had to carry on "married", as she put it "to a man's name but never to know the protection of this nominal husband... never to feel or show preference for any friend not of my own sex."

Caroline was now in a position to spend more time writing. One of the first factory reform poems, A Voice from the Factories (1836) and The Dream and Other Poems (1840) had received good reviews. One critic described her as the "Byron of Modern Poetesses". In 1845 Caroline published her most ambitious poem, The Child of the Islands. Written in honour of the Prince of Wales, the poem warns the infant prince never to forget the poor who are exploited by a privileged upper class.

Caroline Norton took great pride in her writing. In the preface of one of her novels she explained: "The power of writing has always been to me a source of intense pleasure... It has been my best solace in hours of gloom; and the name I have earned as an author in my native land is the only happy boast of my life." (44) She also admitted that in a good year she earned £1,400 by her writings.

In 1848 George Norton was short of money. Many years previously Norton had set up a Trust Fund for Caroline Norton and his sons. He needed permission to get access to this money and offered George a deal. This involved a deed of separation and paying Caroline £600 a year in return for him to be allowed to draw money from the Trust Fund.

Lord Melbourne died in November, 1848. He made a deathbed declaration that he had not had a sexual relationship with Caroline Norton. He also left instructions to his relatives to make financial provision for her. In June, 1851, Caroline's mother died leaving her £480 a year. When he found out about these inheritances, George decided to end his payment of £600 to his wife.

Caroline Norton now broke her agreement by referring her creditors to her husband. As a result a court case began on 18th August, 1853, when Thrupps, the carriage-makers, sued George Norton for £47. The case hinged on the 1848 deed of separation. In court, George Norton, maintained he had only offered £600 a year on condition Caroline had no money from other sources such as Lord Melbourne. Caroline easily exposed this as a lie, but the court decided in George's favour as it was illegal for a married woman to make a contract.

George Norton wrote to The Times where he once again accused his wife of having an affair with Lord Melbourne. As a result of this intervention his solicitor wrote to the newspaper disassociating himself from what his client had said. Sir John Bayley, a leading judge, also joined the debate and accused Norton of being dishonest and greedy. Norton replied that Bayley was "infatuated" with his wife.

In 1851 Norton's novel, Stuart of Dunleath: A Story of Modern Times, a story based on her own experiences, was highly praised by the critics. In the novel she condemns adultery and it is claimed that when a man burst into her bedroom with the words "adultery is a crime, not a recreation". Claire Tomalin has argued that "she was so disappointed and disgusted with her experience of sex within marriage as to lack any wish at all to embark on extra-marital ventures of that kind."

Ernest Sackville Turner has argued that the "Common Law of England, in the early part of the 19th century the nineteenth century, granted a wife fewer rights than had been accorded to under the later Roman law, and hardly more than had been conceded to an African slave before emancipation... The husband... owned her body, her property, her savings, her personal jewels and her income, whether they lived together or separately." Turner goes on to point out, that the husband "could legally support his mistress on the earnings of his wife".

John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, was one of the few men who was willing to speak up for women: "She can acquire no property, but for the husband: the instant it becomes hers, even if by inheritance, it becomes ipso facto his... This is her legal state. And from this state she has no means to withdraw herself. If she leaves her husband she can take nothing with her, neither her children nor anything which is rightfully her own. If he chooses he can compel her to return by law, or by physical force; or he may content himself with seizing for his own use anything which she may earn or which may be given to her by her relations. It is only separation by a decree of a court of justice which entitles her to live apart without being forced back into the custody of an exasperated jailer."

In 1850 a Royal Commission had recommended that the government took a look into the workings of the Divorce Law. Robert Rolfe, 1st Baron Cranworth, took up the challenge and when he was appointed Lord Chancellor he began to draw up new legislation. Caroline Norton contacted Cranworth and requested that he included a clause that would ensure that wives could retain their own property after marriage.

Barbara Leigh Smith, the daughter of Benjamin Leigh Smith, the Radical MP for Norwich, joined the campaign, and published Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854). It included the following passage: "A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture. A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus."

As part of her campaign she published the pamphlet, English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (1854). She explained that after years of experiencing violence from her husband she was unable to obtain a divorce: "I consulted whether a divorce 'by reason of cruelty' might not be pleaded for me; and I laid before my lawyers the many instances of violence, injustice, and ill-usage, of which the trial was but the crowning example. I was then told that no divorce I could obtain would break my marriage; that I could not plead cruelty which I had forgiven; that by returning to Mr Norton I had 'condoned' all I complained of. I learnt, too, the law as to my children – that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them – for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney."

Caroline Norton also wrote a letter to Queen Victoria complaining about the position of women in regards to divorce. "If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself. She has no means of proving the falsehood of his allegations... If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband, however profligate he may be. No law court can divorce in England. A special Act of Parliament annulling the marriage, is passed for each case. The House of Lords grants this almost as a matter of course to the husband, but not to the wife. In only four instances (two of which were cases of incest), has the wife obtained a divorce to marry again."

A group of women, including Barbara Leigh Smith, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale, organised a petition demanding equal legal rights with men. The petition signed by 26,000 men and women was submitted to Parliament. It was accepted by John Stuart Mill in the House of Commons and Lord Henry Brougham in the House of Lords. "The subject was almost entirely new to public consideration, and, as was natural, the feeling both in support of and in opposition to change was very strong. It would disrupt society, people said; it would destroy the home, and turn women into loathsome, self-assertive creatures no one could live with."

The proposed Marriage and Divorce Act was discussed at great length in 1857. William Ewart Gladstone, the future leader of the Liberal Party, was a strong opponent of the bill as he saw it as undermining the authority of the Church. He made seventy-three interventions against the bill, twenty-nine of them in the course of one protracted sitting. However, he was in a small minority and could only gain the support of a "few dozen votes".

In the House of Lords, John Bird Sumner, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry Phillpotts, Bishop of Exeter, both supported the measure and became law in January, 1858. Its main purpose was to transfer jurisdiction on divorce from Parliament and the ecclesiastical courts to a new tribunal. This simplified proceedings and radically lowered divorce costs, thereby making it available to a larger section of the population. Actions for "criminal conversations" were abolished.

The new law did not treat men and women on a equal basis. A man could divorce a woman if she was "guilty of adultery". However, the woman could only obtain a divorce if she could show that "her husband has been guilty of incestuous adultery, or of bigamy with adultery, or of rape, or of sodomy or bestiality, or of adultery coupled with such cruelty as without adultery would have entitled her to a divorce, or of adultery coupled with desertion, without reasonable excuse, for two years or upwards."

Four of the causes in the new act were based on Caroline Norton's experiences as a married woman. (Clause 21) A wife deserted by her husband might be protected if the possession of her earnings from any claim of her husband upon them. (Clause 24) The courts were able to direct payment of separate maintenance to a wife or to her trustee. (Clause 25) A wife was able to inherit and bequeath property like a single woman. (Clause 26) A wife separated from her husband was given the power of contract and suing, and being sued, in any civil proceeding.

For over twenty-five years Caroline had been a close friend of Sir William Stirling-Maxwell. However, George Norton refused to give his wife a divorce and so was prevented from living with him. This situation changed when George died and in 1877 Caroline Norton, now aged 69, married Stirling-Maxwell. Unfortunately, Caroline died three months later.

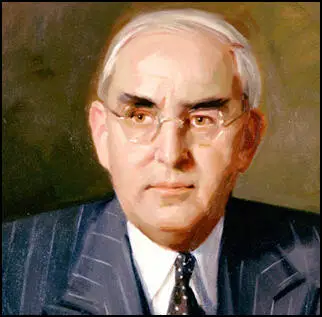

On this day in 1884 Arthur H. Vandenberg was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His father went bankrupt in 1893 and Vandenberg was forced to leave school. He later complained: "I had no youth. I went to work when I was nine, and I never got a chance to enjoy myself." After studying law at the University of Michigan he went into journalism.

In 1906 he was appointed as managing editor of the Grand Rapids Herald at a salary of $2,500. At the time he was a progressive member of the Republican Party and advocated "moderate and practical reforms" on domestic matters. According to Thomas E. Mahl: "By 1928 the man who had dropped out of college for lack of money was a millionaire. His diligence had made him board chairman of Federated Publications, which published not only the Grand Rapids Herald but the Battle Creek Enquirer and News and the Lansing State Journal. Now he could afford the political career he had long wished to pursue."

Vandenberg became senator from Michigan on the March 1928 death of Woodbridge Nathan Ferris. One political commentator claimed that he was "the only Senator who can strut sitting down". Walter Trohan, who worked for the Chicago Tribune, wrote: "I knew Vandenberg quite well... I confess I was not fond of him... Politicians as a class are vain but he was vain beyond most of the tribe. His chief conversation was on his last speech or the one he had in preparation."

Vandenberg was a supporter of the New Deal and in 1933 he managed to push through federal insurance on bank deposits. In 1934 he became one of the few Republicans to be elected to the Senate. In fact he was known as a "New Deal Republican". However, he later opposed the measures introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the basis of "constitutionalism".

Vandenberg viewed the First World War as a mistake and he campaigned to take the profits out of war. On 8th February, 1934, Gerald Nye submitted a Senate Resolution calling for an investigation of the munitions industry by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under Key Pittman of Nevada. Pittman disliked the idea and the resolution was referred to the Military Affairs Committee. It was eventually combined with one introduced earlier by Vandenberg.

The Military Affairs Committee accepted the proposal and as well as Nye and Vandenberg, the Munitions Investigating Committee included James P. Pope of Idaho, Homer T. Bone of Washington, Joel B. Clark of Missouri, Walter F. George of Georgia and W. Warren Barbour of New Jersey. John T. Flynn, a writer with the New Republic magazine, was appointed as an advisor and Alger Hiss as the committee's legal assistant.

Public hearings before the Munitions Investigating Committee began on 4th September, 1934. In the reports published by the committee it was claimed that there was a strong link between the American government's decision to enter the First World War and the lobbying of the the munitions industry. The committee was also highly critical of the nation's bankers. In a speech in 1936 Gerald Nye argued that "the record of facts makes it altogether fair to say that these bankers were in the heart and center of a system that made our going to war inevitable".

Arthur H. Vandenberg had a reputation as a womanizer. Arthur Krock, a journalist with New York Times, later wrote: "Vandenberg's romantic impulses led to gossip at Washington hen-parties, where the hens have teeth and the teeth are sharp". One of his mistresses was Mitzi Sims, the wife of Harold Sims, who was a diplomat at the British embassy. The reporter, Walter Trohan, claimed that insiders called him the "Senator from Mitzi-gan".

Only seventeen Republicans remained in the Senate after the 1936 election. After the party's defeat Vandenberg was considered the leader of the Republicans in the Senate and was expected to become the party candidate in the 1940 presidential election. David Tompkins, the author of Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg: the Evolution of a Modern Republican (1970): "During 1937 most opinion polls rated him as the Republican voters' first choice for the nomination."

During this period Vandenberg changed from being an isolationist into an internationalist. Arthur Krock has argued that he had been "converted from isolationism by the pretty wife of a West European diplomat, a lady of whom, as the saying goes, he saw a lot." Walter Trohan claims that he had seen Office of Naval Intelligence files that showed that Mitzi Sims was a spy working for British intelligence."

In December 1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a speech where he proposed selling munitions to Britain and Canada. Isolationists like Vandenberg and Thomas Connally of Texas argued that this legislation would lead to American involvement in the Second World War. In early February 1941 a poll by the George H. Gallup organisation revealed that only 22 percent were unqualifiedly against the President's proposal. It has been argued by Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998), has argued that the Gallup organization had been infiltrated by the British Security Coordination (BSC).

Michael Wheeler, the author of Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics: The Manipulation of Public Opinion in America (2007) has pointed out how this could have been done: "Proving that a given poll is rigged is difficult because there are so many subtle ways to fake data... a clever pollster can just as easily favor one candidate or the other by making less conspicuous adjustments, such as allocating the undecided voters as suits his needs, throwing out certain interviews on the grounds that they were non-voters, or manipulating the sequence and context within which the questions are asked... Polls can even be rigged without the pollster knowing it.... Most major polling organizations keep their sampling lists under lock and key."

It has been argued that both Vandenberg and Connally were targeted by British Security Coordination in order to persuade the Senate to pass the Lend-Lease proposal. Mary S. Lovell, the author of Cast No Shadow (1992) believes that the spy, Elizabeth Thorpe Pack (codename "Cynthia") who was working for the BSC, played an important role in this: "Cynthia's second mission for British Security Coordination was to try and convert the opinions of senators Connally and Vandenberg into, if not support, a less heated opposition to the Lend Lease bill which literally meant the difference between survival and defeat for the British. Other agents of both sexes were given similar missions with other politicians... with Vandenberg she was successful; with Senator Connally, chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, she was not."

During the Lend-Lease debate Arthur H. Vandenberg announced on the floor of the Senate that he had finally decided to support the loan. He warned his colleagues: "If we do not lead some other great and powerful nation will capitalize our failure and we shall pay the price of our default." Richard N. Gardner, the author of Sterling Dollar Diplomacy in Current Perspective (1980), has argued that Vandenberg's speech was the "turning point in the Senate Debate" with sixteen other Republicans voting in favour of the bill.

Vandenberg was a delegate to the United Nations Conference at San Francisco in 1945 and served on the Committee on Foreign Relations (1947-49). He was a member of Congress until his death on 18th April, 1951.

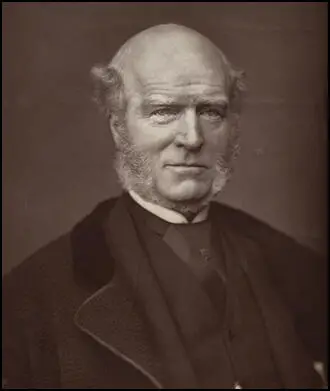

On this day in 1896 Thomas Hughes died. Hughes, the son of a landowner from Uffington in Berkshire, was born on 20th October, 1822. After being educated at Oriel College, Oxford, Hughes trained as a lawyer. While a student Hughes read The Kingdom of Christ (1838) by Frederick Denison Maurice. In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions.

Hughes became a supporter of Chartism and after the decision by the House of Commons to reject the Chartist Petition in 1848, he joined with Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley to form the Christian Socialist movement. The men discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class.

The Christian Socialists published two journals, Politics of the People (1848-1849) and The Christian Socialist (1850-51). The group also produced a series of pamphlets under the title Tracts on Christian Socialism. Other initiatives included a night school in Little Ormond Yard and helping to form eight Working Men's Associations. In 1854 the evening classes that the Christian Socialists had been involved in developed into the establishment of the Working Men's College.

In 1856 Hughes wrote Tom Brown's Schooldays (1856) based on his school experiences at Rugby School. His follow-up novel, Tom Brown at Oxford was less successful. Hughes became a Liberal MP between 1865 and 1874 and principal of the Working Men's College from 1872 to 1883.

On this day in 1933 Nazi Germany opens its first concentration camp at Dachau. On 27th February, 1933, someone set fire to the Reichstag. Several people were arrested including a leading, Georgi Dimitrov, general secretary of the Comintern, the international communist organization. Adolf Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night."

Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and KPD were arrested and sent to Germany's first concentration camp at Dachau, a village a few miles from Munich. The head of the Schutzstaffel (SS), Heinrich Himmler was placed in charge of the operation, whereas Theodor Eicke became commandant of the first camp and was staffed by members of the SS Death's Head units.

Originally called re-education centres the Schutzstaffel (SS) soon began describing them as concentration camps. They were called this because they were "concentrating" the enemy into a restricted area. Hitler argued that the camps were modeled on those used by the British during the Boer War. According to Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "Theodor Eicke, a rough unstable character whose violent and unruly behaviour had already given Himmler many headaches. At last Himmler found an ideal backwater for his troublesome subordinate and sent him off to Dachau."

Theodor Eicke later recalled: "There were times when we has no coats, no boots, no socks. Without so much as a murmur, our men wore their own clothes on duty. We were generally regarded as a necessary evil that only cost money; little men of no consequence standing guard behind barbed wire. The pay of my officers and men, meagre though it was, I had to beg from the various State Finance Offices. As Oberführer I earned in Dachau 230 Reichmark per month and was fortunate because I enjoyed the confidence of my Reichsführer (Himmler). At the beginning there was not a single cartridge, not a single rifle, let alone machine guns. Only three of my men knew how to operate a machine gun. They slept in draughty factory halls. Everywhere there was poverty and want. At the time these men belonged to SS District South. They left it to me to take care of my men's troubles but, unasked, sent men they wanted to be rid of in Munich for some reason or another. These misfits polluted my unit and troubled its state of mind. I had to contend with disloyalty, embezzlement and corruption."

With the support of Heinrich Himmler things began to improve: "From now on progress was unimpeded. I set to work unreservedly and joyfully; I trained soldiers as non-commissioned officers, and non-commissioned officers as leaders. United in our readiness for sacrifice and suffering and in cordial comradeship we created in a few weeks an excellent discipline which produced an outstanding esprit de corps. We did not become megalomaniacs, because we were all poor. Behind the barbed-wire fence we quietly did our duty, and without pity cast out from our ranks anyone who showed the least sign of disloyalty. Thus moulded and thus trained, the camp guard unit grew in the quietness of the concentration camp.

Rudolf Hoess, one of the guards at Dachau, later recalled: "I can clearly remember the first flogging that I witnessed. Eicke had issued orders that a minimum of one company from the guard unit must attend the infliction of these corporal punishments. Two prisoners who had stolen cigarettes from the canteen were sentenced to twenty-five lashes each with the whip. The troops under arms were formed up in an open square in the centre of which stood the Whipping block.Two prisoners were led forward by their block leaders. Then the commandant arrived. The commander of the protective custody compound and the senior company commander reported to him. The Rapportfiihrer read out the sentence and the first prisoner, a small impenitent malingerer, was made to lie along; the length of the block. Two soldiers held his head and hands and two block leaders carried out the punishment, delivering alternate strokes. The prisoner uttered no sound. The other prisoner, a professional politician of strong physique, behaved quite differently. He cried out at the very first stroke and tried to break free. He went on screaming to the end, although the commandant yelled at him to keep quiet. I was standing in the first rank and was compelled to watch the whole procedure. I say compelled, because if I had been in the rear I would not have looked. When the man began to scream I went hot and cold all over. In fact the whole thing, even the beating of the first prisoner made me shudder. Later on, at the beginning of the war, I attended my first execution, but it did not affect me nearly so much as witnessing that first corporal punishment."

Hermann Langbein arrived in Dachau on 1st May 1941. He later wrote in Against All Hope (1992): "On May 1, 1941, I arrived in Dachau together with many other Austrian veterans of the Spanish Civil War. For over two years, we had been interned in camps in southern France, and only internees who live together day and night can get to know one another as well as we did... The general expressions of support from the old political prisoners that greeted us, the first large group of veterans of the Spanish Civil War to arrive in Dachau, did us good morally and in some instances helped us concretely as well."

Langbein was shocked by conditions in the camp. "We had to march out at dawn onto the parade ground for early morning roll call. It was always a dreadful military ceremony. Everyone had to stand bolt upright in rows. The order hats off had to be done with total precision. If there was some mistake or other, then there were punishment exercises. Then the SS took the roll call - to check whether the numbers tallied. That was always the most important thing in every concentration camp - the numbers had to be right at every roll call. No one was allowed to be absent. It made no difference if someone had died during the night - the body would be laid out and included in the roll. And then, when roll call was over, we had to form up into our working parties. And every working party had its own assembly area, which one had to know in order to line up. And then the parties set off for work - depending on whether one was working inside the camp or outside. The outside parties were escorted by SS men. The working day was determined by the time of year. Work was determined by hours of daylight, not the clock. The parties could only leave camp when it was already half-light, so that people couldn't escape under cover of darkness."

Langbein was able to survive the experience by gaining a job in the camp hospital: "A German Communist who had been interned for many years - presented me to his SS boss, who had a request for a clerk from the prison hospital... The Work Assignments man told him that no other inmates were available who had the proper qualifications - the ability to spell correctly, use a typewriter, and take shorthand. He had prepared me in advance to answer the SS questions in such a way that I made a positive impression. With surprising speed, I was placed on a detail with exceptionally good working conditions. Because we also slept in the infirmary, we were not subject to the harassing checks in the blocks. We did not need to show up for the morning and evening roll calls, and we had a roof over our heads as we did our physically undemanding work."

By 1943 Dachau controlled a vast network of camps stretching into Austria. Although not an extermination camp, a large number of inmates were murdered. Others died during medical experiments. Prisoners at Dachau included Leon Blum, Martin Niemoller, Kurt von Schuschnigg, Franz Halder and Hjalmar Schacht.