On this day on 15th March

On this day in 44 BC Julius Caesar was assassinated. When Caesar returned to Rome in 47 BC he appointed 300 of his supporters as members of the Senate. Although the Senate and Public Assembly still met, it was Caesar who now made all the important decisions. By 44 BC Caesar was powerful enough to declare himself dictator for life. Although in the past Roman leaders had become dictators in times of crisis, no one had taken this much power.

A whole range of magnificent buildings named after Caesar and his family were erected. Hundreds of sculptures of Caesar, most of them made by captured Greek artists, were distributed throughout the Roman Empire. Some of the statues claimed that Caesar was now a God. Caesar also became the first living man to appear on a Roman coin. Even the month of the year that he was born, Quintilis, was renamed July in his honour.

Caesar began wearing long red boots. As the ancient kings used to wear similar boots, rumours began to spread that Caesar planned to make himself king. Caesar denied these charges but the Roman people, who had a strong dislike of the kingship system, began to worry about the way Caesar was dominating political life.

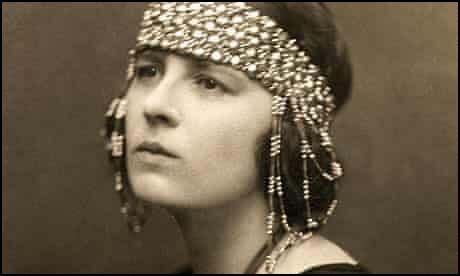

Cleopatra, Ptolemy XIV and Caesarion visited Rome in summer 46 BC. They stayed in one of Caesars country houses. Members of the Senate disapproved of the relationship between Cleopatra and Caesar, partly because he was already married to Calpurnia Pisonis. Others objected to the fact that she was a foreigner. Cicero disliked her for moral reasons: "Her (Cleopatra) way of walking... her clothes, her free way of talking, her embraces and kisses, her beach-parties and dinner-parties, all show her to be a tart."

Later Plutarch attempted to explain why some men found her attractive: "Her actual beauty, it is said, was not in itself remarkable... but the attraction of her person, joining with the charm of her conversation... was something bewitching. It was a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice, with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to another, so that there were few of the nations that she needed an interpreter... which was all the more surprising because most of her predecessors, scarcely gave themselves the trouble to acquire the Egyptian tongue."

Caesar attempted to gain the full support of the people by declaring his intention to lead a military campaign against the Parthians. However, many had doubts about the wisdom of trying to increase the size of the Roman Empire. They believed it would be better to concentrate on organising what they already had.

Rumours began to spread that Caesar planned to make himself king. Plutarch wrote: "What made Caesar hated was his passion to be king." Caesar denied these charges but the Roman people, who had a strong dislike of the kingship system, began to worry about the way Caesar made all the decisions. Even his friends complained that he was no longer willing to listen to advice. Finally, a group of senators decided to kill Caesar.

Even some of Caesar's closest friends were concerned about his unwillingness to listen to advice. Eventually, a group of 60 men, including Marcus Brutus, rumoured to be one of Caesar's illegitimate sons, decided to assassinate Caesar.

Plans were made to carry out the assassination in the Senate just three days before he was due to leave for Parthia. When Julius Caesar arrived at the Senate a group of senators gathered round him. Publius Servilius Casca stabbed him from behind. Caesar looked round for help but now the rest of the group pulled out their daggers. One of the first men Caesar saw was Brutus and was reported to have declared, "You too, my son." Caesar knew it was useless to resist and pulled his toga over his head and waited for the final blows to arrive.

Afterwards Cicero commented: "Caesar subjected the Roman people to oppression... Is there anyone, except Antony who did not wish for his death or who disapproved of what was done?... Some didn't know of the plot, some lacked courage, others the opportunity. None lacked the will."

On this day in 1554 Thomas Wyatt was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death. Thomas Wyatt, the eldest son of Thomas Wyatt, the poet, was born in around 1520. He was brought up as a Catholic. He was married at sixteen to Jane Hawte. Through her he acquired the manor of Wavering. Over the next few years she gave birth to ten children.

After the death of his father in 1542 he developed a reputation for wild living. In 1543 Wyatt and his friend, Henry Howard, got drunk and went on a window-breaking spree in London. They were arrested and brought before the privy council on 1st April, and were charged with acts of violence. He remained in the Tower of London until 3rd May.

Wyatt fought under Howard at the Siege of Landrecies in 1544. It was later claimed that Wyatt distinguished himself during the battle. He also took part in the Siege of Boulogne. Howard wrote to Henry VIII highly commended Wyatt's "hardiness, painfulness, circumspection, and natural disposition to the war". He remained in France until the surrender of Boulogne in 1550.

During the final illness of Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey was married to Guildford Dudley, fourth son of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, as part of the scheme to make sure of a Protestant succession. Jane Grey was declared queen three days after Edward's death. However, she was forced to abdicate nine days later in favour of Edward's sister, Mary Tudor.

Wyatt gave his support to the new queen until he heard she planned to marry Philip of Spain. In January, 1554, Thomas Wyatt accepted the invitation from Edward Courtenay, to join in a general insurrection throughout the country against the marriage. Based at Rochester Castle, Wyatt soon had fifteen hundred men under his command.

When Mary Tudor heard about Wyatt's actions, she issued a pardon to his followers if they returned to their homes within twenty-four hours. Some of his men took up the offer. However, when large number of the army sent to arrest Wyatt changed sides, he controlled a force of 4,000 men. He now felt strong enough to march on London.

On 1st February, 1554, Mary addressed a meeting in the Guildhall where she proclaimed Wyatt a traitor. The next morning, 20,000 men enrolled their names for the protection of the city. The bridges over the Thames within a distance of fifteen miles were broken down and on 3rd February, a reward of land of the annual value of one hundred pounds a year was offered to the person who captured Wyatt.

By the time Thomas Wyatt entered Southwark, large numbers of his army had deserted. However, he continued to march towards St. James's Palace, where Mary Tudor had taken refuge. Wyatt reached Ludgate at two o'clock in the morning of 8th February. The gate was shut against him, and he was unable to break it down. Wyatt now went into retreat but he was captured at Temple Bar.

Wyatt was taken to the Tower of London and on 15th March he was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death. At the scaffold on Tower Hill on 11th April he made a speech claiming that Princess Elizabeth had not been involved in the plot against her sister.

On this day in 1791 Charles Knight is born. Charles Knight, the son of Charles Knight, a bookseller, was born in Windsor on 15th March, 1791. One of his customers was King George III. On one morning he was horrified to find the king reading in his shop, a copy of The Rights of Man by Tom Paine. Although the king made no comment the book was soon banned and Paine was charged with seditious libel.

In 1812 Knight began writing for The Globe. Later that year Knight and his father began publishing the Windsor and Eton Express. Other publishing ventures included The Plain Englishman, The London Guardian and Knight's Quarterly Magazine.

In March 1828 Charles Knight joined with Henry Brougham to form the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Knight became the society's publisher and over the next few years produced the Quarterly Journal of Education (1831-36), Penny Magazine (1832-45) and Penny Cyclopedia (1833-44). Other innovations included the publication in parts of The Pictorial Bible (1836), The Pictorial History of England (1837), Pictorial Shakespeare (1838) and Biographical Dictionary (1846).

Charles Knight's Penny Magazine sold 200,000 copies a week. Richard Altrick, the author of The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public (1957), has pointed out: "Knight... went to great trouble and expense to obtain good woodcuts. Like the publishers of number-books, he seems to have consciously intended this emphasis upon pictures as a means of bringing printed matter to the attention of a public unaccustomed to reading. Even the illiterate found a good pennyworth of enjoyment in the illustrations each issue of the Penny Magazine contained. And these, perhaps more than the letterpress, were responsible for the affection with which many buyers thought of the magazine in retrospect."

Some of Knight's business ventures were very successful. For example, the 27 volume, Penny Cyclopedia were very popular. Others were complete failures and when the publication of the Biographical Dictionary lost £5,000, the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge came to an end.

Knight continued with the idea of pictorial part-works. In 1847 he began The Land We Live In, that contained pictures and descriptions of everything noteworthy in England. The following year he started the weekly periodical, The Voice of the People, but it only lasted for three weeks.

The English Cyclopedia, a revised version of the Penny Cyclopedia appeared between 1853-61, and the Popular History of England (1856-1862). Knight said that his latest venture was "to trace through our annals the essential connection between our political history and our social history" that will enable the people to "learn their own history - how they have grown out of slavery, out of feudal wrong, out of regal despotism - into constitutional liberty, and the greatest estate of the realm.". Knight also wrote his autobiography, Passages of a Working Life (1864).

Charles Knight died on 9th March, 1873.

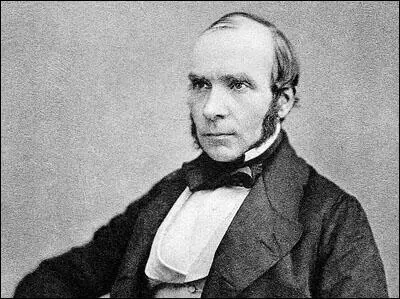

On this day in 1813 John Snow, the eldest of the nine children of William Snow and his wife, Frances Askham Snow, was born in York on 15th March 1813. His father was a labourer and the family lived in one of the poorer parts of town.

According to Sandra Hempel, the "Snows... were an honest, respectable, God-fearing and industrious family with a bent for self-improvement and a strong sense of social duty. One of John's brothers went on to become a clergyman, another ran a temperance hotel, while two of his sisters opened a school."

At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to William Hardcastle, a surgeon apothecary in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In 1831 Hardcastle and Snow attended the poor during the cholera epidemic of 1831–2, including the miners at Killingworth Colliery.

It had a lasting impact on Snow and resulted in him wanting the answers to several questions: "How, exactly, did it affect the body? How was it being spread? Why were some people struck down and not others? Why did so few medical men succumb? Why had he himself emerged unscathed from the midst of so much sickness?"

Cholera was one of the most fatal diseases in the 19th century. Nausea and dizziness led to violent vomiting and diarrhoea, "with stools turning to a grey liquid until nothing emerged but water and fragments of intestinal membrane... extreme muscular cramps followed, with an insatiable desire for water". It is estimated that 16,000 people died during the 1831-1832 epidemic.

Only working-class people appeared to suffer from cholera. Stories began to circulate that doctors were spreading the disease as an excuse for getting their hands on corpses to dissect. Charles Greville, secretary to the Privy Council, noted in his diary: "The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken."

Rioting broke out all over Britain. Crowds of men, women and children smashed windows at the Toxteth Park Cholera Hospital in Liverpool and pelted members of the local board of health with bricks. On 2nd September 1832, violence erupted in Manchester when a mob Swan Street Hospital, breaking down the gates and fighting a pitched battle with the police. This was as a result of a local man, John Hare, discovering that his grandson's body, who had died of cholera, had been smuggled out of the hospital by a doctor who wanted to dissect it.

John Snow attended sessions at the Newcastle School of Medicine in 1832–3, under John Fife. On completing his apprenticeship he became assistant, first to John Watson, general practitioner in Burnopfield, and then to Joseph Warburton, general practitioner in Pateley Bridge.

During this period Snow read a pamphlet, The Return to Nature or Defence of the Vegetable Regimen (1822) by John Frank Newton. Snow was convinced by Newton's arguments that man's natural sustenance was fruit and vegetables, and thought that flesh-eating a perverse custom that caused "derangement" in the stomach and liver, an "undue impetus" to the brain, disorders of the skin and inflammation of the whole system". He also believed that all drinking water should be distilled, including that used for making tea. Newton also objected to the killing of "poor defenceless animals" and the drinking of alcohol.

As a result of this pamphlet Snow became a vegetarian and joined the temperance movement and made a promise to abstain from all alcohol for life. Snow like many people dealing with problems in working-class communities, believed that alcohol was an aggravation of every social evil. "The economic waste of expenditure on drink lowers the standard of living and reduces a great many families to destitution, who, if their incomes were usefully spent, would enjoy a reasonable degree of comfort. Universal temperance would undoubtedly bring incalculable benefits and blessings."

In 1836 John Snow joined the York Temperance Society and overcoming his shyness he addressed a public meeting on the subject. This was at a time when most people considered alcohol to be "highly beneficial to the health, warming and stimulating to the system, and increasing energy and physical strength... for a medical man to decry its use and refuse to prescribe it was seen at best as eccentric and by some doctors and patients as positively negligent".

Snow moved to London and enrolled at the School of Medicine in Great Windmill Street School. Six months' surgical practice at Westminster Hospital completed Snow's training and he became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in May 1838. Four months later he set up in practice at 54 Frith Street, Soho, and also worked in the out-patient department of Charing Cross Hospital.

After the 1847 General Election, Lord John Russell became leader of a new Liberal government. The government proposed a Public Health Bill. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business."

Supporters of Edwin Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by Thomas Southwood Smith, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated.

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of cholera in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. In his report, published in 1842, Chadwick had pointed out that nearly all these deaths had occurred in those areas with impure water supplies and inefficient sewage removal systems. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation.

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848.

In 1849 cholera killed over 50,000 people. John Snow published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera where he argued against the theory of miasmatism (a belief that diseases are caused by noxious form of air emanating from rotting organic matter). He pointed out the disease affected the intestines not the lungs. Snow suggested the contamination of drinking water as a result of cholera evacuations seeping into wells or running into rivers.

John Snow became a member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1850. John Snow developed a reputation as the city's leading anaesthetist and published several articles on the subject in the London Medical Gazette. In April 1853, Snow gave chloroform to Queen Victoria for the birth of her son, Leopold. She wrote in her journal: "The effect was soothing, quieting and delightful beyond measure."

In August 1854 cholera cases began to appear in Soho. Snow investigated all 93 local deaths. He concluded the local water supply had become contaminated, for nearly all the victims used water from the Broad Street pump. At a nearby prison, conditions were far worse, but few deaths. Snow concluded that this was because it had its own well. On 7th September he requested the parish Board of Guardians to disconnect the pump. Sceptical but desperate, they agreed and the handle was removed. After this very few cases were reported.

In 1855, Snow gave his views to a House of Commons Select Committee set up to investigate cholera. Snow argued that cholera was not contagious nor spread by miasmata but was water-borne. He advocated the government invested in massive improvements in drainage and sewage. It has been claimed that his research "played some part in the investment by London and other major British cities in new main drainage and sewage systems."

John Snow had poor health throughout his life and on 10th June 1858, he suffered a stroke. His condition deteriorated and he died on 16th June at his home at 18 Sackville Street, Piccadilly, London. Post-mortem examination showed evidence of old pulmonary tuberculosis and advanced renal disease.

On this day in 1874 Harold L. Ickes was born in Frankstown, Pennsylvania on 15th March, 1874. He attended the University of Chicago and after graduating in 1897 he set himself up as a lawyer. Ickes held progressive political views and often worked for causes he believed in without pay.

As a young man he was deeply influenced by the politics of John Altgeld. He later wrote: "How the Chicago Tribune and others had smeared this humane and courageous man because he had fought for the underdog, and especially because he had pardoned those who still lived of the innocent victims who had been railroaded to the penitentiary after the Haymarket riot! So far as I could see, Altgeld stood about where I wanted to stand on social questions."

Ickes worked for Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 presidential election. After the demise of the Progressive Party, Ickes switched to Hiram Johnson and managed his unsuccessful campaign to became a presidential candidate in 1924.

Ickes became a follower of Franklin D. Roosevelt after being impressed by his progressive policies as governor of New York. In 1932 Ickes played an important role in persuading progressive Republicans to support Roosevelt in the presidential election. He was a supporter of the New Deal. As he later argued: "Many billions of dollars could properly be spent in the United States on permanent improvements. Such spending would not only help us out of the depression, it would do much for the health, well-being and prosperity of the people. I refuse to believe that providing an adequate water supply for a municipality or putting in a sewage system is a wasteful expenditure of money. Any money spent in such fashion as to make our people healthier and happier human beings is not only a good social investment, it is sound from a strictly financial point of view. I can think of no better investment, for instance, than money paid out to provide education and to safeguard the health of the people."

In 1933 Roosevelt appointed Ickes as his Secretary of the Interior. This involved running the Public Works Administration (PWA) and over the next six years spent more than $5,000,000,000 on various large-scale projects. Ickes, a strong supporter of civil rights, he worked closely with Walter Francis White of the NAACP to establish quotas for African American workers in PWA projects.

Harold L. Ickes work was praised by the New York Times: "Mr. Ickes knows all the rackets that infest the construction industry. He is a terror to collective bidders and skimping contractors. He warns that the PWA fund is a sacred trust fund and that only traitors would graft on a project undertaken to save people from hunger. He insists on fidelity to specifications; cancels violated contracts mercilessly, sends inspectors to see that men in their eagerness to work are not robbed of pay by the kickback swindle."

Ickes felt that others in the administration, such as Harry L. Hopkins, had more power and influence over Roosevelt's decision. Ickes did not get on with Harry S. Truman and resigned from his government in 1946 in protest over the appointment of Edwin W. Pauley, Under Secretary of the Navy.

In his final years Ickes wrote a syndicated newspaper column and contributed regularly to the New Republic. Ickes wrote several books including New Democracy (1934), Back to Work: The Story of the PWA (1935), Yellowstone National Park (1937), The Third Term Bugaboo: A Cheerful Anthology (1940), Fighting Oil: The History and Politics of Oil (1943) and The Autobiography of a Curmudgeon (1943).

Harold Ickes died in Washington on 3rd February, 1952. The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes, was published posthumously in 1953.

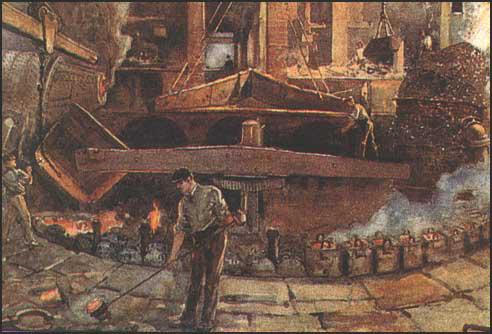

On this day in 1898 Henry Bessemer died. Bessemer was born in Hitchen, Hertfordshire on 19th January 1813. He learned metallurgy in his father's type foundry and made numerous inventions such as a typesetting machine and finding new ways of making gold paint and lead pencils. He also invented a new machine for sugar refining.

During the Crimean War (1853-56) he patented a process by which molten pig-iron could be turned directly into steel by blowing air through it in a converter. This cut out the wrought-iron stage and dramatically reduced the cost of producing steel.

In 1859 Bessemer established a steelworks at Sheffield and began producing guns and steel rails. British entrepreneurs were slow to make use of Bessemer's converter but Andrew Carnegie saw it on a trip to England and made a fortune using this method to produce steel in the United States.

Henry Bessemer died on 15th March 1898.

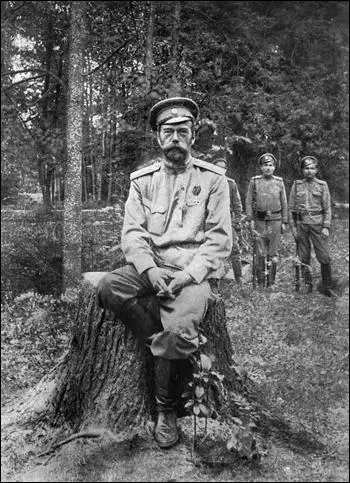

On this day in 1917 Tsar Nicholas II of Russia abdicates the Russian throne, ending the 304-year Romanov dynasty. As Nicholas was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, went to see the Tsar: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration there had been a severe food crisis."

Buchanan then went on to talk about Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna: "I next called His Majesty's attention to the attempts being made by the Germans, not only to create dissension between the Allies, but to estrange him from his people. Their agents were everywhere at work. They were pulling the strings, and were using as their unconscious tools those who were in the habit of advising His Majesty as to the choice of his Ministers. They indirectly influenced the Empress through those in her entourage, with the result that, instead of being loved, as she ought to be, Her Majesty was discredited and accused of working in German interests."

In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics".

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs."

The First World War was having a disastrous impact on the Russian economy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. By January 1917 the price of commodities in Petrograd had increased six-fold. In an attempt to increase their wages, industrial workers went on strike and in Petrograd people took to the street demanding food. On 11th February, 1917, a large crowd marched through the streets of Petrograd breaking shop windows and shouting anti-war slogans. Petrograd was a city of 2,700,000 swollen with an influx of of over 393,000 wartime workers. According to Harrison E. Salisbury, in the last ten days of January, the city had received 21 carloads of grain and flour per day instead of the 120 wagons needed to feed the city. Okhrana, the secret police, warned that "with every day the food question becomes more acute and it brings down cursing of the most unbridled kind against anyone who has any connection with food supplies."

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle reported details of serious food shortages: "All attention here is concentrated on the food question, which for the moment has become unintelligible. Long queues before the bakers' shops have long been a normal feature of life in the city. Grey bread is now sold instead of white, and cakes are not baked. Crowds wander about the streets, mostly women and boys, with a sprinkling of workmen. Here and there windows are broken and a few bakers' shops looted."

It was reported that in one demonstration in the streets by the Nevsky Prospect, the women called out to the soldiers, "Comrades, take away your bayonets, join us!". The soldiers hesitated: "They threw swift glances at their own comrades. The next moment one bayonet is slowly raised, is slowly lifted above the shoulders of the approaching demonstrators. There is thunderous applause. The triumphant crowd greeted their brothers clothed in the grey cloaks of the soldiery. The soldiers mixed freely with the demonstrators." On 27th February, 1917, the Volynsky Regiment mutinied and after killing their commanding officer "made common cause with the demonstrators".

The President of the Duma, Michael Rodzianko, became very concerned about the situation in the city and sent a telegram to the Tsar: "The situation is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The Government is paralysed. Transport, food, and fuel supply are completely disorganised. Universal discontent is increasing. Disorderly firing is going on in the streets. Some troops are firing at each other. It is urgently necessary to entrust a man enjoying the confidence of the country with the formation of a new Government. Delay is impossible. Any tardiness is fatal. I pray God that at this hour the responsibility may not fall upon the Sovereign."

On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges."

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing the Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps."

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Nicholas became increasingly concerned about his safety when is own "bodyguards had deserted and marched to the Duma to offer their services."

Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed."

Nicholas and his family went to live at Tsarskoye Selo. He told Pavel Milyukov, the foreign minister in the new Provisional Government wanted to go into exile in the United Kingdom. Milyukov contacted David Lloyd George, the prime minister. Lloyd George had always been hostile to the rule of the Tsar and had commented on his abdication that it was "worth the whole war and its terrible sacrifices."

In March 1917, David Lloyd George had sent a telegram to Prince George Lvov, the new head of the Provisional Government that stated: "It is with sentiments of the profound satisfaction that the people of Great Britain... have learned that their great ally Russia now stands with the nations which they base their institutions upon responsible government. We believe that the Revolution is the greatest service which they (the Russian people) have yet made to the cause for which the Allied peoples have been fighting since August 1914. It reveals the fundamental truth that this war is at bottom a struggle for popular government as well as for liberty."

Lloyd George gradually changed his mind and two weeks later told George Riddell that Russia was "not sufficiently advanced for a republic". He agreed to help the Tsar claiming he was a "virtuous and well-meaning Sovereign who became directly responsible for a regime drenched in corruption, debauchery, favouritism, jealously, sycophantic idolatry, incompetence and treachery." However, George V, could not help doubting... on grounds of general expediency whether it is advisable that the Imperial Family should take up their residence in this country."

On 19th March 1917, the British government reluctantly offered the family asylum. The British ambassador Sir George Buchanan gave the news to Milyukov on the 23rd and pointed out that the Russian government would have to "make suitable provision for their maintenance." When news reached Britain that Nicholas II was being held under house arrest until he was ready to leave, George V sent him a telegram: "Events of last week have deeply depressed me. My thoughts are constantly with you and I shall always remain your true and devoted friend, as you know I always have been in the past."

The news that the Tsar would be allowed to live in Britain brought protests from the Labour Party. There were also complaints from Lord Francis Bertie, the British ambassador in Paris: "I do not think that the ex-Emperor and his family would be welcome in France. The Empress is not only a Bosche by birth but in sentiment. She did all she could to bring about an understanding with Germany. She is regarded as a criminal or a criminal lunatic and the ex-Emperor as a criminal from his weakness and submission to her promptings."

Sir George Buchanan warned the king that left-wing extremists would use the ex-Tsar's presence "as an excuse for rousing public opinion against us" and the people might start demanding the overthrow of the British monarchy. George V now changed his mind and contacted Arthur Balfour the Foreign Secretary and "begged" him "to represent to the Prime Minister that, from all he hears and reads in the press, the residence in the country of the ex-Emperor and Empress would be strongly resented by the public and would undoubtedly compromise the position of the King and Queen." Under pressure from the king, David Lloyd George withdrew the offer of political asylum in Britain.

In July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky, the new prime minister, sent the royal family to Tobolsk. In March 1918, After the Bolsheviks took power, the Romanovs were moved to Ekaterinburg. Soon afterwards, members of the Czech Legion, were approaching the town. It was believed that these men were attempting to rescue the Tsar and his family. It was decided to execute the family and to destroy the bodies "in order not to give the counter-revolutionaries an opportunity of using the bones of the Tsar to play on the ignorance and the superstition of the masses."

On the 16th July, 1918, the royal family and their servants were told to go into the cellar because they feared an attack from the Czech Legion. Soon after they arrived in the cellar they were told they were to be executed. Nicholas, his wife, his son Alexei, his four daughters, and members of his staff were shot. The bodies were wrapped in blankets, loaded on a truck, and driven to a deserted mine shaft several miles outside the city. The bodies were cut up, soaked in benzene and sulphuric acid, and burned. The charred remains were dumped into a swamp some distance from the mine.

Yakov Sverdlov explained what happened to a meeting of the Soviet Council of People's Commissars on 18th July. "I wish to announce that we have received a report that in Ekaterinburg, in accordance with the decision of the regional Soviet, Nicholas has been shot. Nicholas wanted to escape. The Czechoslovaks were approaching the city. The presidium of the Central Executive Committee has decided to approve this act."

The following day published an official announcement of the execution of the former Tsar which stated that "the wife and son of Nicholas Romanov were sent to a safe place." It seems that Lenin took the view that the killing of the Tsarina and her five children would be unacceptable to the Russian public. It would also have been difficult to justify the murder of the Tsar's physician, cook, chambermaid and waiter.

On this day in 1939 the German Army invades Czechoslovakia. The country was created in 1918 from territory that had previously been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As well as the seven million Czechs, two million Slovaks, 700,000 Hungarians and 450,000 Ruthenians there were three and a half million German speaking people living in Czechoslovakia.

Eduard Benes became foreign minister of the new country. He worked hard for the League of Nations and attempted to obtain good relations with other nations in Europe. Benes replaced Tomas Masaryk when he retired as president in 1935.

Although Czechoslovakia had never been part of Germany, these people liked to call themselves Germans because of their language. Most of these people lived in the Sudetenland, an area on the Czechoslovakian border with Germany. The German speaking people complained that the Czech-dominated government discriminated against them. German's who had lost their jobs in the depression began to argue that they might be better off under Hitler.

Adolf Hitler wanted to march into Czechoslovakia but his generals warned him that with its strong army and good mountain defences Czechoslovakia would be a difficult country to overcome. They also added that if Britain, France or the Soviet Union joined on the side of Czechoslovakia, Germany would probably be badly defeated. One group of senior generals even made plans to overthrow Hitler if he ignored their advice and declared war on Czechoslovakia.

In September 1938, Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, met Hitler at his home in Berchtesgaden. Hitler threatened to invade Czechoslovakia unless Britain supported Germany's plans to takeover the Sudetenland. After discussing the issue with the Edouard Daladier (France) and Eduard Benes (Czechoslovakia), Chamberlain informed Hitler that his proposals were unacceptable.

Adolf Hitler was in a difficult situation but he also knew that Britain and France were unwilling to go to war. He also thought it unlikely that these two countries would be keen to join up with the Soviet Union, whose communist system the western democracies hated more that Hitler's fascist dictatorship.

Benito Mussolini suggested to Hitler that one way of solving this issue was to hold a four-power conference of Germany, Britain, France and Italy. This would exclude both Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, and therefore increasing the possibility of reaching an agreement and undermine the solidarity that was developing against Germany.

The meeting took place in Munich on 29th September, 1938. Desperate to avoid war, and anxious to avoid an alliance with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier agreed that Germany could have the Sudetenland. In return, Hitler promised not to make any further territorial demands in Europe. Adolf Hitler, Neville Chamberlain, Edouard Daladier and Benito Mussolini signed the Munich Agreement which transferred the Sudetenland to Germany.

When Eduard Benes, Czechoslovakia's head of state, protested at this decision, Neville Chamberlain told him that Britain would be unwilling to go to war over the issue of the Sudetenland.

The German Army marched into the Sudetenland on 1st October, 1938. As this area contained nearly all the country's mountain fortifications, she was no longer able to defend herself against further aggression. By March 1939 the whole of Czechoslovakia was under the control of Germany. The Czech Army was disbanded and the Germans took control of the country's highly developed arms industry.

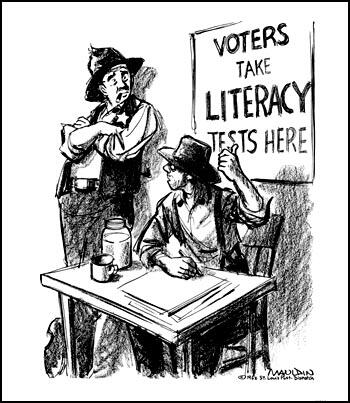

On this day in 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson tells U.S. Congress "We shall overcome" while advocating the Voting Rights Act. After the American Civil War many state governments in the Deep South employed literacy tests as part of the voter registration process. These tests were intended to disenfranchise racial minorities. In July 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. The legislation attempted to deal with the problem of African Americans being denied the vote in the Deep South. The legislation stated that uniform standards must prevail for establishing the right to vote. Schooling to sixth grade constituted legal proof of literacy and the attorney general was given power to initiate legal action in any area where he found a pattern of resistance to the law.

The following year, President Johnson attempted to persuade Congress to pass his Voting Rights Act. This proposed legislation removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes."

Although opposed by politicians from the Deep South, the Voting Rights Act was passed by large majorities in the House of Representatives (333 to 48) and the Senate (77 to 19). The legislation empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

When Johnson signed the 1965 Civil Rights Act he made a prophecy that he was “signing away the south for 50 years”. This proved accurate. In fact, the Democrats have never recovered the vote of the white racists in the Deep South.

Just before his assassination in 1968, Robert Kennedy forecast that the United States would have a “Negro president” in 40 years. This prediction came true when Barack Obama was elected in November 2008. However, his Republican rival, John McCain, won the former Confederate states of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee.

Bill Mauldin, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (15th May 1962)

On this day in 1983 Rebecca West died at 48 Kingston House North, South Kensington. She was buried at Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking.

Cicely Fairfield (Rebecca West), the youngest of three children (all daughters) of Charles Fairfield (1843–1906) and his wife, Isabella Campbell Mackenzie (1853–1921), was born at 28 Burlington Road, Westbourne Park, on 21st December, 1892. Her father, an anti-socialist journalist, left the family when she was a child. Her feeling of desertion by her father persisted for the remainder of her life."

Cicely's mother was a talented pianist, having come from a musical family. Her brother, the violinist and composer Alick Mackenzie, was president of the Royal Academy of Music (1888–1924). After her husband left the family home, Isabella took her three children to her native Edinburgh.

Cicely attended George Watson's Ladies' College (1904–7). Although highly intelligent her headmistress did not encourage her to go to university. At first she wanted a career in the theatre and while studying at the Academy of Dramatic Art (1910–11), she took the name Rebecca West after the heroine of Ibsen's Rosmersholm). However, she had developed strong left-wing opinions and decided to become a journalist instead.

Three veterans of the women's suffrage campaign, Dora Marsden, Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe, began publishing their a feminist journal, The Freewoman on 23rd November, 1911. In its first edition Rebecca West wrote an article in support for free-love: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

This article created a storm. Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication".

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Edmund Haynes, Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

On 21st March 1912 Stella Browne wrote about her views on free-love in The Freewoman: "The sexual experience is the right of every human being not hopelessly afflicted in mind or body and should be entirely a matter of free choice and personal preference untainted by bargain or compulsion." According to her biographer, Lesley A. Hall: "Browne emphasized the need for women to speak about their own experiences. In both principle and practice Stella was a convinced believer in free love, known to have had various lovers, certainly some male, and possibly some female, though these cannot be reliably identified."

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Edmund Haynes (Divorce Reform), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Rebecca West, Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Rebecca West became very active in the socialist movement and joined the Fabian Society and met George Bernard Shaw at one of its summer schools. In 1912 she became a staff member of The Clarion. She soon developed a reputation as a perceptive reviewer. When she reviewed the novel, Marriage, she described the author, H. G. Wells, "the old maid among novelists". Wells responded by inviting West to his home. Soon afterwards they became lovers and a son, Anthony Panther West, was born on 4th August 1914.

Her biographer, Bonnie Kime Scott, has argued: "West's affair brought her a domesticity which she disliked, and rustication to various places discreetly accessible to Wells, already notorious for extramarital affairs. She happily settled in her own London flat in 1919." Her first novel, Return of the Soldier (1918), was about a soldier from the First World War suffering from shell-shock. This was followed by the novelsThe Judge (1922), The Strange Necessity (1928) and Harriet Hume (1929). She also wrote a study of the author D. H. Lawrence (1930). She also wrote articles for the Daily News, The Star, New Statesman and New Republic.

Rebecca West married Henry Andrews (1894–1968) on 1st November 1930. West continued to take a keen interest in politics and was a supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She joined with Emma Goldman, Sybil Thorndyke, Fenner Brockway and C. E. M. Joad to establish the Committee to Aid Homeless Spanish Women and Children.

Bonnie Kime Scott has pointed out: "Rebecca West has gradually gained recognition as a perceptive and independent interpreter of literature... West's accounts of literature and culture are typically grounded in philosophical paradigms and cultural diagnoses that invite critical study today. She found pervasive examples of Manichaeism, and joined anthropologists of her era in detecting examples of Western degeneracy."

After the Second World War West became more conservative in her political views and wrote for the Daily Telegraph and the New Yorker. Some of her work was extremely anti-communist and some critics, including Arthur Schlesinger and J. B. Priestley, accused of her being in sympathy with McCarthyism - a charge she denied.

Other books published by Rebecca West included The Meaning of Treason (1949), The Fountain Overflows (1957), The Court and the Castle (1958), The Birds Fall Down (1966), McLuhan and the Future of Literature (1969) and 1900 (1982).

Rebecca West died on 15th March 1983 at 48 Kingston House North, South Kensington. She was buried at Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking.