On this day on 5th December

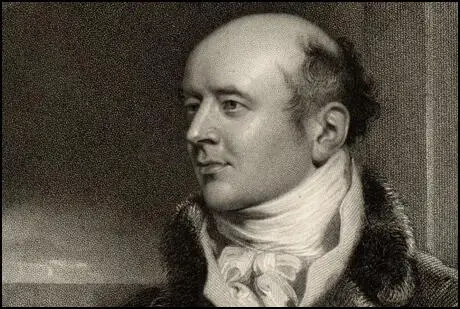

On this day in 1756 campaigning journalist James Perry died. Perry, the son of a builder, was born in Aberdeen on 30th October, 1756. He attended Aberdeen University but was forced to leave when his father's building business collapsed. After a period working in a draper's shop, Perry became an actor. However, while working in Edinburgh Perry was told his strong Scottish accent would prevent him from having a career on the stage.

In 1777 Perry moved to London where he made his living by writing essays and poems for The General Advertiser. His contributions on the trial of Admiral Augustus Keppel helped to increase circulation of the newspaper to several thousand copies a day. Perry began to develop radical political ideas, but fearing prosecution, he published he anonymously several political pamphlets.

Perry was now in great demand as a journalist and after editing the European Magazine (1782-83) he moved to the London Gazette. Perry edited the newspaper for eight years but when it was purchased by a group of Tories, he left and in 1789 he formed a partnership with James Gray and purchased the Morning Chronicle from William Woodfall. The newspaper now became a firm supporter of the Whigs in Parliament. At first the paper did not make money and Perry, Gray and their printer, John Lambert, all lived in the same house together.

Perry's support for parliamentary reform brought him into conflict with the authorities and in 1793 was charged with seditious libel. Defended by Thomas Erskine, the jury decided that he was "guilty of publishing, but with no malicious intent". The judge refused to accept the verdict and after another day's discussion, decided he was "not guilty". Perry and Gray were less fortunate in 1798 when they were found guilty of libelling the House of Lords and sentenced to three months in Newgate Prison.

Sales of the Morning Chronicle gradually increased and by 1810 the newspaper had a circulation of 7,000. Perry was now able to recruit Britain's best radical journalists, including William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. Perry continued to be hounded by the government and in February 1818 was charged with Leigh Hunt and The Examiner for criticizing King George III. Perry defended himself well in court and was found not guilty.

In 1817 Perry developed an internal disease that compelled him to undergo several hospital operations. John Black was appointed as the new editor of Morning Chronicle. When he failed to improve, his doctor suggested that he should live by the sea. This was also unsuccessful and James Perry died in Brighton on 5th December, 1821.

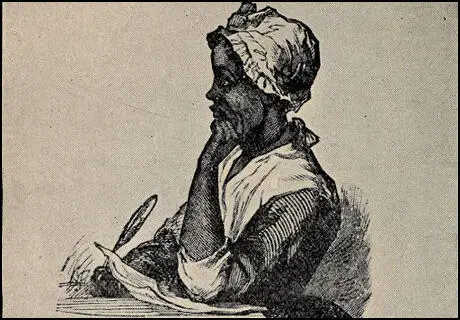

On this day in 1784 Phillis Wheatley slave and poet died. Phillis was born in Senegal in about 1753. She was captured by slave traders and brought to America in 1761. Purchased by John Wheatley, a tailor from Boston, Phillis was taught to read by one of Wheatley's daughters. Phillis studied English, Latin and Greek and in 1767 began writing poetry. Her first poem, on the death of George Whitefield, was published in 1770.

When Phillis was eighteen she travelled to London and while there the Countess of Huntingdon, helped her publish a collection of her work, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773).

After the death of John Wheatley and his wife, Phillis married John Peters, a free black man, who ran a small grocery store in Boston. The business was unsuccessful and Phillis was forced to find work as a servant. Phillis Wheatley died in poverty in Boston on 5th December, 1784.

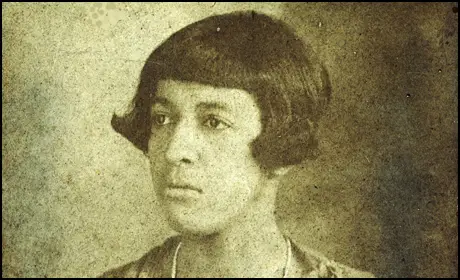

On this day in 1874 Henriette Raynouard was born in Rueil-Malmaison in Paris. When she was a teenager she began a friendship with Léo Claretie, a writer who was twelve years older than her. They were married in 1893 and over the next few years she had two children. She later recalled: "I was raised like all the other young girls of my time… I never left my parents until the day of my marriage... bad feelings unexpectedly arose... our characters did not complement one another; on several occasions, I was at the point of breaking off the union, but I had two children, two girls, and for them I waited."

In 1907 Henriette began having an affair with Joseph Caillaux, who was Minister of Finance in the French government. In 1908, Henriette divorced her husband, Léo Claretie but Caillaux remained married to his wife.

On 27th June, 1911 Caillaux became prime minister. While holding this position he upset a large number of people in France by making territorial concessions to the German colony of Cameroon. Caillaux, who was attempting to prevent a war over Morocco. Caillaux favored a policy of conciliation with Germany and this created a great deal of controversy.

Caillaux also caused a scandal when he divorced his wife and he married Henriette in October 1911. Caillaux and his ministers were forced to resign on 11th January, 1912, after it was revealed that he had secretly negotiated with Germany without the knowledge of the President.

Caillaux was accused of being a pacifist in 1913 when he opposed an extension to conscription. This resulting in a press campaign against Caillaux. It was later claimed that two of Callaux's political rivals, Louis Barthou and Raymond Poincare, organised this attack. It was rumoured that Gaston Calmette, the editor of Le Figaro, had obtained some love letters sent by Henriette to Caillaux, when he was still married to his first wife, and intended to publish them in his newspaper.

On 13th March 1914, Calmette published an intimate letter Joseph Caillaux had written thirteen years earlier to Berthe Gueydan, the mistress who later became his first wife. Henriette Caillaux became convinced that he would now publish her letters to Caillaux. Three days later Henriette went to visit Calmette in his office in Paris. She asked, "You know why I have come?" Calmette replied: "Not at all, Madame". As Edward Berenson, the author of The Trial of Madame Caillaux (1992) has pointed out: "Without another word, Henriette pulled her right hand from the mass of fur protecting it. In her fist was a small weapon, a Browning automatic. Six shots went off in rapid succession, and Calmette fell to the floor clutching his abdomen." Calmette died six hours later.

Henriette Caillaux's trial took place in July 1914. It was claimed that reporters had paid as much as $200 for their seats in the court-room. Journalists who covered the case included Walter Duranty, Wythe Williams and Alexander Woollcott. Henriette was defended in court by Fernand Labori who had previously defended Emile Zola and Alfred Dreyfus.

According to Herbert Mitgang of the New York Times: "Henriette Caillaux's testimony shifted back and forth between literary and scientific images. It was intended to make her appear a heroine of uncontrollable emotions to the jury, and a victim of deterministic laws to the experts. Literature made a woman of ungovernable passions sympathetic, even attractive; criminal psychology placed her beyond the law. After a seven-day trial in the Cour d'Assises in Paris, Henriette Caillaux walked out free. In less than an hour of deliberations, the all-male jury decided the homicide was committed without premeditation or criminal intent. The jurors accepted her testimony that when she pulled the trigger, she was a temporary victim of (as her lawyer put it) unbridled female passions."

Joseph Caillaux now returned to politics and led the opposition against France's involvement in the First World War. Caillaux worked hard to achieve a negotiated peace. In November 1917 George Clemenceau became prime minister. He immediately clamped down on dissent and Caillaux and Louis Malvy, another senior politician opposed to the war, were both arrested for treason. Caillaux was eventually tried in 1920. Although acquitted on the treason charge he was convicted of corresponding with Germany during the war and banished from France and deprived of his civil rights for ten years.

Henriette Caillaux became a student at the École du Louvre and completed a thesis on the sculptor Jules Dalou. She published a book on Dalou in 1935. She died on 29th January 1943.

On this day in 1899 civil rights activist Modjeska Monteith was born. She attended Benedict College, South Carolina and after graduating in 1921 became a schoolteacher at the Booker T. Washington School in Columbia. When she married Andrew Simkins, a prosperous African American businessman, she was forced to resign as the local public school system did not allow married women to teach.

In 1931 Simkins found employment with the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association. Her role was to raise funds and assist in health education among African Americans. Shocked by the poverty she witnessed, Simkins became more concerned with politics and joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

Modjeska Simkins established clinics for tuberculosis testing at churches, schools and cotton mills. She also published a newsletter and arranged for annual meetings with other African American leaders. The South Carolina Tuberculosis Association became concerned about her political activities and in 1941 she was told that she would have to leave the NAACP. When Simkins refused she was fired.

A popular lecturer on civil rights, in 1942 Simkins was appointed secretary of the South Carolina Conference of the NAACP. In this post she undertook lawsuits on behalf of African Americans. Her campaign to force South Carolina to remove racial differences in teachers salaries achieved success in 1944. Simkins next campaign was to persuade the South Carolina Democratic Party to reform its voting system.

In December, 1947, Simkins was one of the fifty-one African American leaders who urged Henry Wallace to run for president as the Progressive Party candidate. The following year Simkins played a prominent role in Wallace's failed attempt to become president. She was also active in the campaign to persuade Congress to pass an Anti-Lynching bill.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s Simkins supported her friends, Benjamin Davis, Paul Robeson and Eslanda Goode in their struggle with the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

In 1949 Simkins began her campaign to end segregation in public schools. Her efforts resulted in the Supreme Court ruling in 1952 that separate schools were acceptable as long as they were "separate and equal". It was not too difficult for the NAACP to provide information to show that black and white schools in the South were not equal. In 1954 the Supreme Court announced that separate schools were not equal and ruled that they were therefore unconstitutional.

In November, 1957, Simkins was removed as state secretary of the NAACP. The main reason for this was that some people objected to Simkins close relationship with the American Communist Party. Although she never joined the party, she was willing to work with its members and had been vocal in her support of those blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

Simkins continued to campaign for desegregation and in 1963 helped her niece to become the first African American student since reconstruction to enter the University of South Carolina. Modjeska Simkins died in 1992.

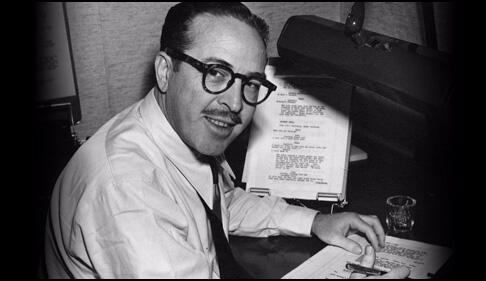

On this day in 1905 Dalton Trumbo was born in Montrose, Colorado. Educated at the University of Colorado. Trumbo wanted to be a writer and by the early 1930s his articles and stories appeared in Saturday Evening Post, McCall's Magazine, Vanity Fair and the film magazine, the Hollywood Spectator .

In 1935 Trumbo published his first novel, Eclipse, a satire about a self-made businessman. Trumbo's most popular novel, Johnny Got His Gun, about a disfigured British officer in the First World War, won a National Book Award in 1939.

In the 1930s Trumbo worked on several movies including Love Begins at Twenty (1936), Road Gang (1936), Tugboat Princess (1936), That Man's Here Again (1937), Devil's Playground (1937), Fugitives For a Night (1938), A Man to Remember (1938) and Career (1939). Trumbo, who joined the American Communist Party in 1943, was also active in the Screen Writers Guild.

Other films written by Trumbo included Five Came Back (1939), Curtain Call (1940) and Kitty Foyle (1940), a film for which he was nominated for an Academy Award Oscar, A Guy Named Joe (1943), Tender Comrade (1943) and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

In 1947 nineteen members of the film industry who were suspected of being communists were called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. This included Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Edward Dmytryk, Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Larry Parks, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

Trumbo appeared before the HUAC on 28th October, 1947. He was denied the right to make an opening statement. In it he wanted to make the point that the HUAC was having a damaging impact on world opinion: "As indicated by news dispatches from foreign countries during the past week, the eyes of the world are focused today upon the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In every capital city these hearings will be reported. From what happens during the proceedings, the peoples of the earth will learn by precept and example precisely what America means when her strong voice calls out to the community of nations for freedom of the press, freedom of expression, freedom of conscience, the civil rights of men standing accused before government agencies, the vitality and strength of private enterprise, the inviolable right of every American to think as he wishes, to organize and assemble as he pleases, to vote in secret as he chooses."

Trumbo was asked by Robert E. Stripling if he was a member of the Screen Writers Guild. He refused to answer the question: "Mr. Stripling, the rights of American labor to inviolably secret membership have been won in this country by a great cost of blood and a great cost in terms of hunger. These rights have become an American tradition. Over the Voice of America we have broadcast to the entire world the freedom of our labor... You asked me a question which would permit you to haul every union member in the United States up here to identify himself as a union member, to subject him to future intimidation and coercion. This, I believe is an unconstitutional question."

Dalton Trumbo also refused to admit he was a member of the American Communist Party. Trumbo was removed from the room and HUAC investigator, Louis Russell, now read out a nine page report on his Communist Party affiliations. John Parnell Thomas now stated: "The evidence presented before this Committee concerning Dalton Trumbo clearly indicates that he is an active Communist Party member. Also the fact that he followed the usual Communist line of not responding to questions of the Committee is definite proof that he is a member of the Communist Party. Therefore, by unanimous vote of the members present, the subcommittee recommends to the full committee that Dalton Trumbo be cited for contempt of Congress." Trumbo was found guilty of contempt of Congress and was sentenced to ten months in prison.

Blacklisted by the Hollywood studios, Trumbo and his wife decided to go and live in Mexico City. They were joined by their friends, Ring Lardner Jr, Ian McLellan Hunter, Hugo Butler, John Bright, Jean Rouverol and Albert Maltz. On Saturday mornings this group and their children used to have picnic lunches and play baseball together. The FBI were spying on them in Mexico and according to declassified reports, the agents believed that these picnics were cover for "Communist meetings." They were later joined by Martha Dodd and Frederick Vanderbilt Field.

Trumbo asked Hunter, who had not yet been blacklisted, to approach William Wyler with an idea for a film. Ring Lardner Jr. explained in his autobiography, I'd Hate Myself in the Morning (2000): "Ian got involved only by agreeing to front for the already-blacklisted Trumbo. It was he who had come up with the idea of a movie about a reporter and a princess on the loose in Rome. Paramount paid $50,000 for what it assumed to be Ian's (but was really Trumbo's) first draft, and hired him to do a rewrite... The result, much to Ian's (and Trumbo's) surprise, was a wonderful movie, starring Gregory Peck and the unknown Audrey Hepburn." In 1953 Roman Holiday won the Academy Award for the best screenplay (Trumbo did not get credit for this work until after the blacklist was lifted).

Trumbo carried on writing screenplays by using pseudonyms such as Ben Parry, Robert Rich and Sally Stubblefield. This included Roman Holiday (1953), which won the Academy Award for best screenplay, Carnival Story (1954), One Man Mutiny (1955), The Boss (1956), The Brave One (1956), another Academy Award winner, The Brothers Rico (1957), The Deerslayer (1957), The Green-Eyed Blonde (1957), The Cowboy (1958) and Terror in a Texas Town (1958).

In 1959 Frank Sinatra announced that he proposed to break the blacklist by employing Albert Maltz as the screenwriter of his proposed film, The Execution of Private Slovik, based on the book by William Bradford Huie. Sinatra soon came under attack for his decision. He nearly came to blows with John Wayne, who called him a "Commie" when they met in the street. However, what really hurt Sinatra was the criticism he received in the press. This included claims that his friend, John F. Kennedy, also wanted an end to the blacklist. Sinatra issued a statement to the press: "I would like to comment on the attacks from certain quarters on Senator John Kennedy by connecting him with my decision on employing a screenwriter. This type of partisan politics is hitting below the belt... I make movies. I do not ask the advice of Senator Kennedy on whom I should hire. Senator Kennedy does not ask me how he should vote in the Senate."

Michael Freedland, the author of Witch-Hunt in Hollywood (2009) argues that "Kennedy didn't like the association with the name of one of the Hollywood Ten. He would soon run from President and he was worried that he could harm him." A few days later Sinatra took out another paid-for advertisement in the newspapers: "In view of the reaction of my family, friends and the American public I've instructed my lawyers to make a settlement with Albert Maltz. My conversations with Maltz indicate that he has an affirmative, pro-American approach to the story, but the American public has indicated it feels that the morality of hiring Maltz is the most crucial matter and I will accept this majority opinion."

In 1960 Dalton Trumbo became the first blacklisted writer to use his own name when he wrote the screenplay for the film Spartacus. Based on the novel by another left-wing blacklisted writer, Howard Fast, is a film that examines the spirit of revolt. Trumbo refers back to his experiences of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. At the end, when the Romans finally defeat the rebellion, the captured slaves refuse to identify Spartacus. As a result, all are crucified. Ironically, much of Spartacus was filmed on land owned by William Randolph Hearst. It was Hearst's newspapers that played such an important role in making McCarthyism possible.

As Ring Lardner Jr., another member of the Hollywood Ten, pointed out in his autobiography, I'd Hate Myself in the Morning (2000): “Sinatra caved in, paying off Maltz in cash and eventually scrubbing the project, perhaps partly out of fear of harming his friend John F. Kennedy, a candidate for President at the time. (Following the election that fall, however, the President-elect and his brother, Attorney-General-to-be Robert Kennedy, crossed a picket line to see Spartacus at a theater in Washington D.C., and pronounced it good.)”

After the blacklist was lifted, Trumbo wrote the screenplay for Lonely Are the Brave (1962), The Sandpiper (1965) and The Fixer (1968). In 1970 Trumbo's anti-war novel, Johnny Got His Gun, was republished. The book had been withdrawn during the Second World War, had a tremendous impact on the generation being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War.

In 1970 Trumbo argued that all screenwriters were victims during McCarthyism. "Some suffered less than others, some grew and some diminished, but in the final tally we were all victims because almost without exception each of us felt compelled to say things he did not want to say, to do things that he did not want to do, to deliver and receive wounds he truly did not want to exchange. That is why none of us - right, left, or centre - emerged from that long nightmare without sin."

Albert Maltz diagreed with this view of the situation. In an interview he gave to the New York Times in 1972 he compared the experiences of Adrian Scott and Edward Dmytryk: "There is currently in vogue a thesis pronounced by Dalton Trumbo which declares that everyone during the years of blacklist was equally a victim. This is factual nonsense and represents a bewildering moral position.... Adrian Scott was the producer of the notable film Crossfire in 1947 and Edward Dmytryk was its director. Crossfire won wide critical acclaim, many awards and commercial success. Both of these men refused to co-operate with the HCUA. Both were held in contempt of the HCUA and went to jail. When Dmytryk emerged from his prison term he did so with a new set of principles. He suddenly saw the heavenly light, testified as a friend of the HCUA, praised its purposes and practices and denounced all who opposed it. Dmytryk immediately found work as a director, and has worked all down the years since. Adrian Scott, who came out of prison with his principles intact, could not produce a film for a studio again until 1970. He was blacklisted for 21 years. To assert that he and Dmytryk were equally victims is beyond my comprehension."

In 1973 Dalton Trumbo joined forces with Donald Freed and Mark Lane to write the political thriller, Executive Action, which dealt with an alleged conspiracy to murder John F. Kennedy. The film opened to a storm of controversy with the suggestion that Kennedy had been a victim of the Military-Industrial Complex and was removed totally from the movie theaters by early December 1973. Dalton Trumbo died of a heart attack in Los Angeles, California, on 10th September, 1976.

On this day in 1910 Abraham Polonsky, the eldest son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was born in New York on 5th December, 1910. In 1928, he entered City College of New York and, following graduation, earned his law degree in 1935 at Columbia Law School.

Polonsky was a member of the Communist Party and for several years worked as a teacher and lawyer. He also wrote novels and eventually moved to Hollywood and wrote Golden Earrings (1948), Body and Soul (1947) and Force of Evil (1948).

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. The HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

One of those named, Bertolt Brecht, an emigrant playwright, gave evidence and then left for East Germany. Ten others: Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz,, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie refused to answer any questions.

Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

Polonsky had been a member of the Communist Party but his friends, including John Howard Lawson and John Garfield, refused to name him as a member. However, eventually he was called to appear before the HUAC in April 1951. Although he was willing to talk about his own political past, he refused to name his former comrades and was blacklisted.

Abraham Polonsky resigned because he rejected the policies of Joseph Stalin. However he remained committed to Marxist political theory, stating in an interview: "I was a Communist because I thought Marxism offered the best analysis of history, and I still believe that."

After the blacklist came to an end Polonsky worked on several films such as Madigan (1968), Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969), Romance of a Horsethief (1971), Avalanche Express (1979) and Monsignor (1982). Polonsky died of a heart attack in Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, on 26th October, 1999.

On this day in 1921 the Football Association attempted to discourage the playing of women's football. The FA issued the following statement: "Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, the Council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged. Complaints have been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of the receipts to other than Charitable objects. The Council are further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to Charitable objects. For these reasons the Council requests the clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches." The FA also announced that members were not allowed to referee or act as linesman at any women's football match.

Some supporters of women's football welcomed the decision of the FA. "Football Girl" wrote a weekly column in the Football Special Magazine. She wrote: "Women's footballers have at last been roused to the necessity of organisation if they are to carry on, and the F.A. ban, having made us independent of outside bodies, has given us the additional impetus that will probably make us organise ourselves far more thoroughly than we should have done if we had been in a half-and-half situation, neither definitely sure of having F.A.'s assistance and yet to a large extent relying on it."

The first meeting of the English Ladies Football Association (ELFA) took place at Blackburn on 10th December 1921. At this time there were approximately 150 ladies' football clubs in England. The representatives of 25 clubs attended the initial meeting. This rose to 60 at the next meeting held in Grimsby.

The ELFA issued a statement that argued: "The Association is most concerned with the management of the game, and intend to insist that all clubs in the Association are run on a perfectly straightforward manner, so that there will be no exploiting of the teams in the interest of the man or firm who manages them."

The ELFA introduced its own set of rules and regulations. This included reducing the size of the pitch. It was also decided to use a lighter football, a change that was eventually adopted by the Football Association. Referees of women's matches were also given "greater powers concerning the use of ball skills rather than brawn".

ELFA also made a rule that any club that became affiliated to the ELFA would not be allowed to play against a team that was not a member. It was believed that the best way of making ELFA strong was to make it difficult for non-members to find matches.

ELFA also took measures to stop a club like Dick Kerr Ladies from developing again in the future. Alfred Frankland had obtained the best players by persuading them to play for his team. ELFA therefore decreed that no woman was to play for a club that was more than twenty miles from her home. The measure did a great deal to encourage clubs to develop local talent.

On this day in 1963 Herbert Lehman, one of the few politicians who stood up against Joseph McCarthy, died in New York City. Lehman was born in New York City on 28th March, 1878. After graduating from Williams College in 1899 Lehman was employed by the textile manufacturers, J. Spencer Turner Company.

During the First World War Lehman served in the United States Army and by 1919 had reached the rank of colonel on the General Staff.

A member of the Democratic Party, Lehman served as lieutenant governor of New York (1929-32), Governor of New York (1933-42) and Director General of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Operations in the State Department (1943-46).

A member of the Public Advisory Boards of the Economic Cooperation Administration, Lehman was elected to the Senate in November 1949, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Robert F. Wagner.

A strong opponent of McCarthyism Lehman was one of the first senators to attack the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. Herbert Lehman retired from the Senate in 1957.

On this day in 1984 Ethel Mannin died of pneumonia and heart failure at Teignmouth Hospital. During her lifetime she had published over a hundred books.

Ethel Mannin, the eldest of the three children of Robert Mannin, a postal worker and Edith Gray, a farmer's daughter, was born in Clapham on 11th October 1900. Her father was a socialist and encouraged her to have a career. In her biography she recalled: "My father does not care how I achieve happiness so long as I achieve it."

Her parents sent her to a local private school: In Confessions and Impressions (1930) she recalled: "The school called itself a preparatory school, hut for what it could possibly prepare anyone it would be impossible to say.... I was so agonisingly shy and timid that I was fair game for the older children's teasing. A group of the older girls would amuse themselves by tormenting me until I would say a funny little obscene word...here was also a girl of about twelve whom I thought both grown-up and beautiful, immeasurably beyond me, but she had nothing but contempt for me. She wore petticoats with wide lace to them, and knickers with coloured ribbons run through. She was fond of doing high kicks-presumably to show off this seductive lingerie. I knew a curious quickening of the senses at the sight of her; she was a dashing and lovely being infinitely removed from me. But I have forgotten her name. I suppose that it is because I unconsciously shrink from the memory of her. She was one of my sadistic persecutors."

As a young girl she began writing stories and the first of these appeared in the Lady's Companion in 1910. In 1915 she won a scholarship to attend a commercial school in London. According to her autobiography, Mannin fell in love with one of her teachers: "I loved her, dear heavens, how I loved her! Once when she kissed me at the end of one of our precious lovely Saturday afternoons I walked home in a trance of ecstasy. I loved her literally so much that it hurt, and she was for me the meaning of all things that are." The teacher was also a a member of the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society: "Through this Miss X I learned about George Bernard Shaw, the Fabians, Jingoism, and the Independent Labour Party."

After leaving school she found employment as a typist for the advertising agency, Charles F. Higham Ltd. She later recalled "I was given twenty-three shillings a week and was tremendously excited and happy." The following year Charles Frederick Higham promoted her to the post of copywriter. "At sixteen I was writing advertisements, running two house-organs - business magazines - and when I was seventeen was publishing my own stories, articles, verses, in a monthly magazine which Higham bought and left to me to produce." Her employer was to have a great influence on her career: "I have never met anyone to equal him; for sheer individuality he stands head and shoulders above all the others. He has a dynamic quality which I have never found in the same degree of intensity in anyone else.... We are alike in that we both know what we want of life and set out to get it by the most direct route and with unfaltering determination."

Mannin began a relationship with an artist who worked for Higham. "Every evening J.S. and I would have tea together and talk... He did most of the talking. I could not talk. I listened and my young mind sucked up knowledge like a sponge absorbing water." He introduced her to the work of Thomas Paine and Robert Green Ingersoll. She later recalled: "I was deeply religious until I was sixteen, and then the artist... who was my real education, put into my hands the essays of Robert Green Ingersoll and Thomas Paine's Age of Reason, together with a Rational Press Association Annual, and I became an agnostic." He also lent her books and articles by John Stuart Mill, William Morris, Upton Sinclair, Eugene V. Debs, Graham Wallas, Robert Cunningham Graham and Peter Kropotkin. On Sunday afternoons they went to Finsbury Park and heard Tom Mann speak.

In her autobiography, Confessions and Impressions (1930), she wrote: "I loved him in the perfervid way in which I had loved my Miss X., but at fifteen I was completely sexually unawakened, and even at sixteen, towards the end of our year's association, any manifestation of love-making from him completely bewildered me. I was sixteen and he was twenty-six. I became sufficiently awakened towards the end of the friendship to want to kiss and to be kissed by him, but any caressive intimacy from him merely troubled me. It seemed queer, and I resented it a little and wished he wouldn't." He was a conscientious objector during the First World War and in 1917 he returned to New Zealand in order to avoid joining the British Army.

In 1918 she became romantically involved with John Alexander Porteus (1885–1956), who was the general manager at Highams. She later wrote that during this period that "this friendship lit by passion" was the "happiest I have ver known". On 28th November, 1919, Mannin married Porteus: "I was a very young nineteen, in spite of the experimental adventurings - too young, and too much in love, to be depressed by the dreary registry office, the cold foggy day, and the fact that we had no money and no home." Soon after her marriage she gave birth to her only child, Jean.

With a young baby to look after, Mannin now worked from home. She still wrote advertisements and edited journals for Charles Frederick Higham: "I had a retainer fee from Higham... and increased my journalistic freelance output, and wrote extensively in the provincial press... My output was tremendous; the payment was small as it always is for a beginner. Eventually she turned to novel writing and published Martha in 1923. According to one critic, the novel "elaborately plots the life of the lovechild of an unmarried woman and the price the child has to pay for the sins of the parents." This was followed by the Hunger for the Sea (1924), Sounding Brass (1925) and Pilgrims (1927). The author of The Feminist Companion to Literature in English has argued that "these are socially and politically conscious works, alert to women's oppression".

In 1929 Mannin and Porteus separated and she bought a small house in Wimbledon. Her first volume of autobiography, Confessions and Impressions appeared in 1930. According to her biographer, Beverly E. Schneller: "In 1931 she published her first book of short stories, Green Figs, and her literary success made her popular with the press, who were eager for her progressive views on sexuality, motherhood and professionalism, and marriage."

Ethel Mannin was a supporter of progressive education and sent her daughter to Summerhill School. In 1931 she published Common Sense and the Child, a book about the educational theories of A. S. Neill. She argued that "all outside compulsion is wrong... inner compulsion is the only value". Mannin also suggested that "there is no such thing as the naughty child... there are only happy children and unhappy children." She also produced a novel, Linda Shawn (1932), on the subject of progressive education. Love's Winnowing (1932) was her first openly politically novel. In 1934 she began an affair with W. B. Yeats.

Mannin was political active and had declared herself to be a socialist in her early twenties. In 1935 she joined the Independent Labour Party and contributed articles to its journal, The New Leader. In 1936 she travelled to the Soviet Union but in her book, South to Samarkland, she expressed her disillusionment with communism although she always remained firmly on the left. Mannin married Reginald Reynolds, a fellow member of the ILP on 23rd December 1938. She became friendly with Emma Goldman and her next novel, Red Rose, was based on the life of her friend.

Mannin produced seven volumes of autobiography and fourteen travel books, recording her visits to Germany, India, Morocco, Burma, Egypt, Jordan, Italy, and elsewhere. In 1958 she published her first children's books. Mannin also published several books on philosophy including Loneliness: a Study of the Human Condition (1966) and Practitioners of Love: some Aspects of the Human Phenomenon (1969).

Virginia Nicholson, the author of Among the Bohemians (2002) argues: "Ethel Mannin didn't resent the passing of youth, but she felt displaced in the post-War world of the 1950s... In old age her pleasures were correspondingly elderly - good wine, good books, and her roses. Her robust impatience with humbug remained vigorous however. She continued to travel, espoused Buddhism, and signed up to a variety of liberal causes. Passion, she felt, was for the young, but 'the unending struggle against injustice and barbarism in the world' was perennial."