Henriette Caillaux

Henriette Raynouard was born at Rueil-Malmaison in Paris on 5th December 1874. When she was a teenager she began a friendship with Léo Claretie, a writer who was twelve years older than her. They were married in 1893 and over the next few years she had two children. She later recalled: "I was raised like all the other young girls of my time… I never left my parents until the day of my marriage... bad feelings unexpectedly arose... our characters did not complement one another; on several occasions, I was at the point of breaking off the union, but I had two children, two girls, and for them I waited."

In 1907 Henriette began having an affair with Joseph Caillaux, who was Minister of Finance in the French government. In 1908, Henriette divorced her husband, Léo Claretie but Caillaux remained married to his wife. On 27th June, 1911 Caillaux became prime minister. While holding this position he upset a large number of people in France by making territorial concessions to the German colony of Cameroon. Caillaux, who was attempting to prevent a war over Morocco. Caillaux favored a policy of conciliation with Germany and this created a great deal of controversy. He also caused a scandal when he divorced his wife and he married Henriette in October 1911. Caillaux and his ministers were forced to resign on 11th January, 1912, after it was revealed that he had secretly negotiated with Germany without the knowledge of the President.

Caillaux was accused of being a pacifist in 1913 when he opposed an extension to conscription. This resulting in a press campaign against Caillaux. It was later claimed that two of Callaux's political rivals, Louis Barthou and Raymond Poincare, organised this attack. It was rumoured that Gaston Calmette, the editor of Le Figaro, had obtained some love letters sent by Henriette to Caillaux, when he was still married to his first wife, and intended to publish them in his newspaper.

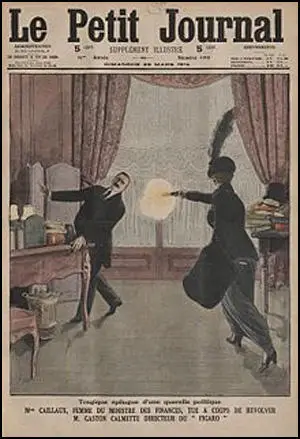

On 13th March 1914, Calmette published an intimate letter Joseph Caillaux had written thirteen years earlier to Berthe Gueydan, the mistress who later became his first wife. Henriette became convinced that he would now publish her letters to Caillaux. Three days later Henriette went to visit Calmette in his office in Paris. She asked, "You know why I have come?" Calmette replied: "Not at all, Madame". As Edward Berenson, the author of The Trial of Madame Caillaux (1992) has pointed out: "Without another word, Henriette pulled her right hand from the mass of fur protecting it. In her fist was a small weapon, a Browning automatic. Six shots went off in rapid succession, and Calmette fell to the floor clutching his abdomen." Calmette died six hours later.

Henriette Caillaux's trial took place in July 1914. It was claimed that reporters had paid as much as $200 for their seats in the court-room. Journalists who covered the case included Walter Duranty, Wythe Williams and Alexander Woollcott. Henriette was defended in court by Fernand Labori who had previously defended Emile Zola and Alfred Dreyfus.

According to Herbert Mitgang of the New York Times: "Henriette Caillaux's testimony shifted back and forth between literary and scientific images. It was intended to make her appear a heroine of uncontrollable emotions to the jury, and a victim of deterministic laws to the experts. Literature made a woman of ungovernable passions sympathetic, even attractive; criminal psychology placed her beyond the law. After a seven-day trial in the Cour d'Assises in Paris, Henriette Caillaux walked out free. In less than an hour of deliberations, the all-male jury decided the homicide was committed without premeditation or criminal intent. The jurors accepted her testimony that when she pulled the trigger, she was a temporary victim of (as her lawyer put it) unbridled female passions."

Joseph Caillaux now returned to politics and led the opposition against France's involvement in the First World War. Caillaux worked hard to achieve a negotiated peace. In November 1917 George Clemenceau became prime minister. He immediately clamped down on dissent and Caillaux and Louis Malvy, another senior politician opposed to the war, were both arrested for treason. Caillaux was eventually tried in 1920. Although acquitted on the treason charge he was convicted of corresponding with Germany during the war and banished from France and deprived of his civil rights for ten years.

Henriette Caillaux became a student at the École du Louvre and completed a thesis on the sculptor Jules Dalou. She published a book on Dalou in 1935.

Henriette Caillaux died on 29th January 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Berenson, The Trial of Madame Caillaux (1992)

On 16 March 1914 at 6 o'clock in the evening Henriette Caillaux was ushered into the office of Gaston Calmette, editor of Le Figaro.... Mme. Caillaux wore a fur coat over a gown strangely formal for a late afternoon business call. Her hat was modest, and a large furry muff linked the two sleeves of her coat. Henriette's hands were hidden inside the muff.

Before Calmette could speak she asked, "You know why I have come?" "Not at all, Madame," responded the editor, charming to the end. Without another word, Henriette pulled her right hand from the mass of fur protecting it. In her fist was a small weapon, a Browning automatic. Six shots went off in rapid succession, and Calmette fell to the floor clutching his abdomen. Figaro workers from the surrounding offices rushed in and seized Mme. Caillaux... "Do not touch me," she ordered her captors. "Je suis une dame!".

(2) Herbert Mitgang, New York Times (11th March, 1992)

Here was no case that might have required the sleuthing services of Hercule Poirot or Inspector Maigret. The society woman held a smoking gun in her hand and never denied that she had committed the deed. It was a murder in cold blood, punishable under French law by life imprisonment or even death.

Henriette Caillaux shot the editor because he had conducted a campaign of vilification against her husband, Joseph, a wealthy former prime minister affiliated with the center-left Radical Party. Or was her motive more a familiar affair of the heart? She had been one of Joseph Caillaux's mistresses; it was a second marriage for both. The Figaro editor, a rightist political enemy, had broken an unwritten Parisian rule by publishing a love letter written to a gentleman's mistress. Joseph Caillaux, a notorious boulevardier, had sent the letter 13 years before the trial to another woman, who later became his first wife, and it had been leaked to Figaro.

Political and social mores, the Napoleonic Code that discriminated against women legally and the venality of the press all came together in the affaire Caillaux.

Her celebrated lawyer, Fernand Labori, had represented Emile Zola and successfully defended Capt. Alfred Dreyfus against false charges of treason in the notorious, anti-Semitic Dreyfus affair. In her clever defense on the witness stand, Henriette Caillaux made two points. She evoked the romantic and idealized notion that women were ruled by their passions; hers was simply a "crime passionnel." She also used new scientific language that stressed the nervous system and the unconscious mind.

Henriette Caillaux's testimony shifted back and forth between literary and scientific images. It was intended to make her appear a heroine of uncontrollable emotions to the jury, and a victim of deterministic laws to the experts. Literature made a woman of ungovernable passions sympathetic, even attractive; criminal psychology placed her beyond the law.

After a seven-day trial in the Cour d'Assises in Paris, Henriette Caillaux walked out free. In less than an hour of deliberations, the all-male jury decided the homicide was committed without premeditation or criminal intent. The jurors accepted her testimony that when she pulled the trigger, she was a temporary victim of (as her lawyer put it) "unbridled female passions."

By digging deeply into the transcripts of the case and newspaper files, Mr. Berenson, a professor of history at the University of California at Los Angeles, has unearthed and reconstructed a highly readable story that touches upon many aspects of life during the so-called Belle Epoque in France.

Under one infamous article of the 1804 Napoleonic Code, "The husband owes protection to his wife, the wife obedience to her husband." The author emphasizes that French attitudes toward women were an important part of the trial and its coverage in the press. Describing the newspaper illustrations, Professor Berenson writes, "Mme. Caillaux stands out starkly as a lone woman speaking to a sea of mustachioed male faces, as a woman subject to their gaze, open to their scrutiny."

Going beyond the trial itself -- and giving his book a modern feminist twist -- Professor Berenson notes that during the Belle Epoque men claimed the existence of natural and hierarchical differences between the sexes. After France's defeat by Prussia in 1870, some commentators attributed a decline in French power to moral decay and to changing relations between the sexes. The author says these commentators attributed France's weaknesses to the emancipation of women, the legalization of divorce and the emasculation of men.

What distinguishes "The Trial of Mme. Caillaux" is its portrait of society before the guns of August 1914 destroyed the illusions of the Belle Epoque. In an epilogue, Professor Berenson writes that World War I gave women important responsibilities on the home front and greater recognition. Even so, it took a second World War before French women won the right to vote.