Spartacus Blog

It is important we remember the Freedom Riders

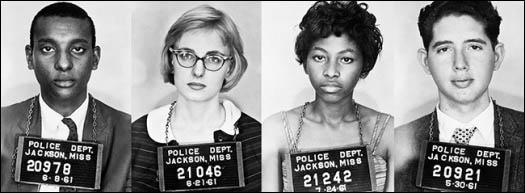

John Lewis died on 17 July, 2020. Some of the obituaries mentioned that in 1961 he was one of the Freedom Riders. He was one of the last of this brave group to die (Diane Nash, James Zwerg and William E. Harbour are still alive). Unfortunately most of them did not get obituaries because unlike Lewis they did not serve in Congress. However, it is important that we remember what these people achieved because those in authority do not like to acknowledge what the United States was like at this time.

It should not be forgotten that Adolf Hitler was a great admirer of the way racial minorities were treated in the United States. In Mein Kampf (1925) Hitler praised America as the one state that has made progress toward a primarily racial conception of citizenship, by “excluding certain races from naturalization.” In 1928, Hitler remarked, approvingly, that white settlers in America had "gunned down the millions of redskins to a few hundred thousand." When he spoke of Lebensraum, the German drive for “living space” in Eastern Europe, he often had America in mind." (1)

According to James Q. Whitman, Professor of Comparative and Foreign Law at Yale Law School: "In the early 1930s the Nazis drew on a range of American examples, both federal and state. Their America was not just the South; it was a racist America writ much larger. Moreover, the ironic truth is that when Nazis rejected the American example, it was sometimes because they thought that American practices were overly harsh: for Nazis of the early 1930s, even radical ones, American race law sometimes looked too racist." (2)

Hans Frank, who was later hung at Nuremberg, edited the National Socialist Handbook for Law and Legislation (1935) It included an article by Herbert Kier on recommendations for race legislation in Nazi Germany. As Ira Katznelson has pointed out, Kier "devoted a quarter of its pages to U.S. legislation - which went beyond segregation to include rules governing American Indians, citizenship criteria for Filipinos and Puerto Ricans as well as African Americans, immigration regulations, and prohibitions against miscegenation in some 30 states. No other country, not even South Africa, possessed a comparably developed set of relevant laws." (3)

Segregation and the Supreme Court

In the 1950s the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was involved in the struggle to end segregation on buses and trains. In 1952 segregation on inter-state railways was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. This was followed in 1954 by a similar judgment concerning inter-state buses. However, states in the Deep South continued their own policy of transport segregation. This usually involved whites sitting in the front and blacks sitting nearest to the front had to give up their seats to any whites that were standing. (4)

African American people who disobeyed the state's transport segregation policies were arrested and fined. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant from Montgomery, Alabama, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man. After her arrest, Martin Luther King, a pastor at the local Baptist Church, helped organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued. (5)

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. Martin Luther King toured the country making speeches urging other groups to take up the struggle against segregation, to spread the "Montgomery experience" across the South". (6)

Congress on Racial Equality

Transport segregation continued in the Deep South, so the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) began to develop strategies to bring it to an end. James Farmer became national director of CORE and in 1960 Genevieve Hughes was appointed as a field secretary. According to Raymond Arsenault: "During the late 1950s she (Hughes) became active in the local chapter of CORE, eventually helping to rejuvenate the chapter by co-ordinating a boycott of dime stores affiliated with chains resisting the sit-in movement in the South. Exhilarated by the boycott and increasingly alienated from the conservative complacency of Wall Street, she gravitated toward a commitment to full-time activism, accepting a CORE field secretary position in the fall of 1960. The first woman to serve on CORE's field staff, she made a lasting impression on everyone who met her." (7) Hughes was once asked why she had joined CORE she replied: "I figured Southern women should be represented to the South and the nation would realize all Southern people don't think alike." (8)

In February, 1961, CORE organised a conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (9) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (10)

Members of CORE who volunteered to join the Freedom Riders included included John Lewis, James Peck, James Farmer, James Zwerg, James Lawson, Genevieve Hughes, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, William E. Harbour, Frances Bergman, Walter Bergman, Diane Nash, Wyatt Tee Walker, Albert Bigelow, William Barbee, Susan Wilbur, Susan Herrmann, Lafayette Bernard, Benjamin Elton Cox, Jimmy McDonald, William Sloane Coffin, John Lee Copeland, Mae Frances Moultrie, Edward Blankenheimand, Salynn McCollum, Frederick Leonard, Lucretia Collins, Paul Brooks and Catherine Burks,

The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included John Lewis, James Peck, Edward Blankenheimand, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (11)

John Lewis, James Peck, Edward Blankenheimand, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman

and James Farmer. Bottom, left to right: Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person,

Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes and Jimmy McDonald.

The second bus left on the 17th May and its passengers included William Barbee, William E. Harbour, Susan Herrmann, Lafayette Bernard, Susan Wilbur, James Zwerg, Salynn McCollum, Frederick Leonard, Lucretia Collins, Paul Brooks and Catherine Burks, Susan Herrmann, 20, a student at Fisk University, Nashville, majoring in psychology, later recalled: "We were all prepared to die - and for a while Saturday I thought all 21 of us would die at the hands of that mob in Montgomery. We did not fight back. We do not believe in violence. We were freedom riders... trying to ride in buses through Alabama to New Orleans to help the cause of true freedom for all the races." (12)

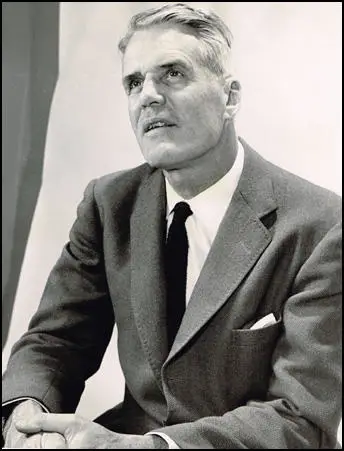

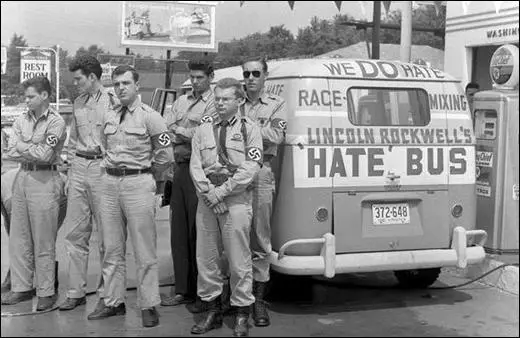

George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party, offered his support to the Ku Klux Klan in their fight against the Freedom Riders. Rockwell secured a Volkswagen van and decorated it with slogans supporting white supremacy, dubbing it the "Hate Bus" and driving it to speaking engagements and party rallies. In one speech Rockwell said: "Anybody that doesn't hate communism and doesn't hate race-mixers, there's something wrong with them." At meetings Nazi Party members carried signs with the words "America for Whites", "Africa for Blacks" and "Gas Chamber for Traitors". (13)

President John F. Kennedy was totally opposed to the Freedom Rides. He called Harris Wofford, the president's Special Assistant for Civil Rights and demanded that he do everything to stop them from taking place: "Kennedy's call to me during the Freedom Rides when he said, without any of his customary humor, 'Stop them! Get your friends off those buses!' He felt that Martin Luther King, James Farmer, Bill Coffin, and company were embarrassing him and the country on the eve of the meeting in Vienna with Khrushchev. He supported every American's right to stand up or sit down for his rights - but not to ride for them in the spring of 1961." (14)

Freedom Riders in Alabama

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They traveled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (15) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (16)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Ku Klux Klan groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and a member of the KKK, reported to his case officer that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. Connor said he wanted the Riders to be beaten until "it looked like a bulldog got a hold of them." It was later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and took no action to prevent the violence. (17)

On 14th May, 1961, a mob of Klansmen, attacked the bus at Anniston, Alabama. Albert Bigelow later explained: "Our bus, approaching Anniston, stopped while our driver conversed with the driver of an outgoing bus. A traveler from the bus leaving Anniston station. Outside, no police were in sight. During the fifteen minutes in Anniston, while the mob slashed tires and smashed windows, one policeman appeared in a brown uniform. He did nothing to stop vandalism but fraternized with the mob. A man in a white overall with a dark blue oval insignia on the breast was friendly with the policemen and consulted from time to time with the most active of the mob. Two policemen appeared and cleared a path. The bus left the station. There were no arrests. A few miles out on the highway to Birmingham a tire blow and we pulled to the roadside, the mob after us in about 50 cars. They surrounded us again, yelling and smashing windows, brandishing clubs, chains and pipes; I saw all three." (18)

Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. One man threw a bomb through a broken window. When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault. (19)

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital." (20)

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that they were taken to the local hospital. "They admitted me into a ward like room not a private room which is what they had in those days and all the black people were kept on gurneys out in in the corridor they were not admitted to the hospital in any formal since nobody had any injuries that I knew of except for smoke inhalation which was fairly serious but more for me because the smoke bomb had been placed in the seat right opposite of mine and I had probably breathed more smoke than anybody else." (21)

Attack in Montgomery

The surviving bus traveled to Birmingham, Alabama. When they arrived at the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station they saw an angry mob. Gary Thomas Rowe was a member of the KKK who had arrived in the town that day: "We made an astounding sight... men running and walking down the streets of Birmingham on Sunday afternoon carrying chains, sticks, and clubs. Everything was deserted; no police officers were to be seen except one on a street corner. He stepped off and let us go by, and we barged into the bus station and took it over like an army of occupation. There were Klansmen in the waiting room, in the rest rooms, in the parking area." (22)

James Zwerg later recalled: "As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up." (23)

The driver had a brief conversation with the white mob. He returned to the bus with a small group of white people and told the passengers: "We have received word that a bus has been burned to the ground and passengers are being carried to the hospital by the carloads. A mob is waiting for our bus and will do the same to us unless we get these blacks off the front seats." The white men began to try and remove Charles Person and Herman K. Harris from the front seat. Walter Bergman and James Peck attempted to intervene but they were soon knocked to the floor. (24)

Harris later testified that there were "two main guys" kicking Bergman, and that they "just kicked him and kicked, just kicked him... his head and shoulders in the back. I thought maybe they would break his, bust his head." The men adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (25)

They adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman, the oldest of the Freedom Riders at sixty-one, was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (26)

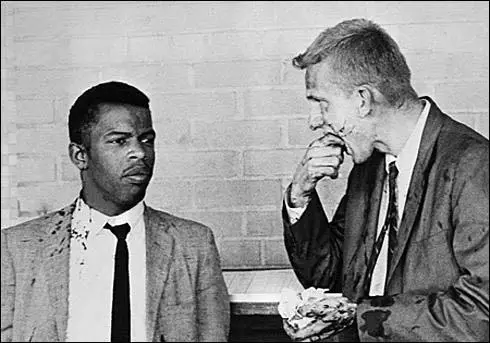

James Zwerg later commented: "There was noting particularly heroic in what I did. If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said 'Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.' And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don't know if he lived or died." (27)

John Lewis was left unconscious in a pool of his own blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal in Montgomery, He spent countless days and nights in county jails. In several cities, police either looked the other way while crowds beat the riders or arrested the so-called outside agitators. During the Freedom Riders campaign the Attorney General, Robert Kennedy telephoned Jim Eastland “seven or eight or twelve times each day, about what was going to happen when they got to Mississippi and what needed to be done. That was finally decided was that there wouldn’t be any violence: as they came over the border, they’d lock them all up.” (28)

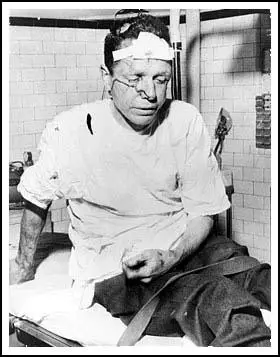

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that it was was James Peck who insisited they continued on the Freedom Ride. "The central figure was Jim Peck and Jim Peck looked like a mummy his head and face were covered with bandages and only his eyes were obvious and his mouth couldn't move and we did have a debate at this occasion about whether to go on. Jim Farmer was not with us. He was back home taking care of a family situation (his father had a serious heart-attack). Jim Peck said we should go on and after that there was not any debate if he couldn't be beaten as he was and still say we should go on we certainly felt we could go on so we all voted unanimously that we would go on and I felt very appalled at seeing Jim Peck but I felt a lot of admiration for him too." (29)

Some of the Freedom Riders, including seven women, ran for safety. The women approached an African-American taxicab driver and asked him to take them to the First Baptist Church. However, he was unwilling to violate Jim Crow restrictions by taking any white women. He agreed to take the five African-Americans, but the two white women, Susan Wilbur and Susan Herrmann, were left on the curb. They were then attacked by the white mob with makeshift weapons. (30)

Herrmann later recalled: "The mob kept closing in and starting yelling 'Get 'em! Get 'em!' They picked up Jim Zwerg of Beloit College in Wisconsin, the only white boy in our group, and threw him on the ground. They kicked him unconscious. Still, we didn't fight back. But we didn't believe in running either. I saw some men hold boys, who were nearly unconscious, while white women hit them with purses. The white women were yelling 'Kill them!' and other nasty shouts. The police came and said they would put us in protective custody. They acted like we were crazy. They just couldn't understand why we would be freedom riders. But even though they did not believe in what we were doing, they did protect us and in that sense upheld the law." (31)

Robert Kennedy and the Freedom Riders

Several years later, government officials would freely acknowledge the heroism and sacrifices of the Freedom Riders but that was not true of 1961. Attorney General Robert Kennedy criticizing the activities of the Freedom Riders as he was worried that support for CORE would hurt the Democratic Party in the Deep South in the 1962 elections. James Farmer was unconvinced by this argument and pointed out that his organization was committed to Gandhian action: "Our philosophy was simple. We put on pressure and create a crisis and then they react." (32)

Robert Kennedy was a close friend of Governor John Patterson of Alabama. Kennedy explained in his interview with Anthony Lewis in 1964. “I had this long relationship with John Patterson (the governor of Alabama). He was our great pal in the South. So he was doubly exercised at me – who was his friend and pal – to have involved him with suddenly surrounding this church with marshals and having marshals descend with no authority, he felt, on his cities… He couldn’t understand why the Kennedys were doing this to him.” (33)

The Attorney General sent John Seigenthaler to negotiate with Governor Patterson of Alabama. Patterson told Seigenthaler that he was more popular than President John F. Kennedy and vowed to hold the line "against Martin Luther King and these rabble-rousers". He added "I want you to know that if schools in Alabama are integrated, blood's gonna flow in the streets, and you take the message back to the President and you tell the Attorney General that." (34)

Harris Wofford, the president's Special Assistant for Civil Rights, later pointed out: "Seigenthaler arrived in time to escort the first group of wounded and shaken riders from the bus terminal to the airport, and flew with them to safety in New Orleans. He had to hurry back, for James Farmer was arriving at the Alabama border with a new group, joined by a contingent from Nashville, including student sit-in leaders James Lawson, John Lewis, and Diane Nash; Lawson, who had studied with Gandhi during three years as a student missionary in India, said they would go by bus all the way to New Orleans, by way of Alabama and Mississippi, or die trying." (35)

John Seigenthaler, tried to drive into the mob to save a young woman who was being attacked, According to Raymond Arsenault, the author of Freedom Riders (2006): "Suddenly, two rough-looking men dressed in overalls blocked his path to the car door, demanding to know who the hell he was. Seigenthaler replied that he was a federal agent and that they had better not challenge his authority. Before he could say any more, a third man struck him in the back of the head with a pipe. Unconscious, he fell to the pavement, where he was kicked in the ribs by other members of the mob. Pushed under the rear bumper of the car, his battered and motionless body remained there until discovered by a reporter twenty-five minutes later." (36)

The attack on Seigenthaler was too much for the Kennedy administration, and it sent in 600 federal marshals to defend the Freedom Riders. Governor Patterson responded by calling out the National Guard. To those who had already experienced the protective custody provided by Bull Connor, the scene was all too familiar. John Lewis pointed out: "Those soldiers didn't look like protectors now. Their rifles were pointed our way. They looked like the enemy." (37)

Robert Kennedy, called for a “cooling-off” period and a halt to the rides. The Freedom Riders refused to do this. Speaking from his hospital bed, James Zwerg, assured reporters that "these beatings cannot deter us from our purpose. We are not martyrs or publicity-seekers. We want only equality and justice, and we will get it. We will continue our journey one way or another. We are prepared to die." (38) William Barbee echoed Zwerg's pledge: "As soon as we're recovered from this, we'll start again... We'll take all the South has to throw and still come back for more." Unfortunately, Barbee was unable to do this as a result of the beating he received he was paralyzed for life and had an early death, (39)

Martin Luther King arrived in Montgomery to give his support to those Freedom Riders. Fred Shuttlesworth and other Civil Rights campaigners, joined John Lewis, Diane Nash, Wyatt Tee Walker who were fit enough to carry on with the ride into the Deep South. Governor Patterson branded the Freedom Riders as "outlaws" and they were forced to take refuge in Montgomery's First Baptist Church. King telephoned the Attorney General to complain about the situation and was not very pleased when he replied: "Now, Reverend, don't tell me that. You know just as well as I do that if it hadn't been for the United States marshals, you'd be dead as Kelsey's nuts right now!" (40)

However, with his attempts to please racist Democratic politicians in the Deep South, he came under attack from the liberal press in the North. For example, The New York Times published an editorial that said: "The issue in Montgomery is the right of American citizens, white and Negro alike, to travel in safety in interstate commerce, without being tested by the so-called Freedom Riders, a racially mixed group consisting primarily of students, who are waging their campaign for civil rights in the South in a Gandhian sprit of idealism and of non-violent resistance to an evil tradition." (41)

Mass Arrests in Mississippi

The Freedom Riders intended to move their protest to Mississippi. President John F. Kennedy made one last attempt to stop this happening and telephoned Martin Luther King to call-off the action and persuade them to post bonds so that they could leave prison. King replied: "It's a matter of conscience and morality. They must use their lives and bodies to right a wrong. Our conscience tells us that the law is wrong and we must resist, but we have a moral obligation to accept the penalty." Kennedy insisted: "That is not going to have the slightest effect on what the government is going to do in this field or any other. The fact that they stay in jail is not going to have the slightest effect on me." (42)

The media was to play an important role in changing the attitudes of the Kennedy administration. On the first bus that left Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi, on 24th May, 1961, the 12 Freedom Riders led by James Lawson, were joined by members of the National Guard and several journalists. The second bus the Freedom Riders were led by John Lewis and the third bus by the Baptist minister, John Lee Copeland. The following day the fourth bus left Montgomery. Those on board included three Baptist ministers, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Wyatt Tee Walker and William Sloane Coffin, chaplain of Yale University. (43)

When the buses arrived at the Jackson Terminal, the Freedom Riders, black and white, went into the white waiting room. Several also used the white rest-room. They were immediately arrested. They refused an offer by NAACP attorneys to post a thousand-dollar bond for each defendant. When the Baptist minister, Ralph Abernathy was asked about Robert Kennedy's complaint that the Freedom Riders were embarrassing the nation in front of the world, he responded: "Well doesn't the Attorney General know we've been embarrassed all our lives?" (44)

During the summer of 1961 freedom riders also campaigned against other forms of racial discrimination. They sat together, in segregated restaurants, lunch counters and hotels. This was especially effective when it concerned large companies who, fearing boycotts in the North, began to desegregate their businesses. Norman Thomas described these young people as "secular saints" (45) I. F. Stone argued: "They and a few white sympathizers as youthful and devoted as themselves have begun a social revolution in the South with their sit-ins and their Freedom Rides. Never has a tinier minority done more for the liberation of a whole people than these few youngsters of C.O.R.E. (Congress for Racial Equality) and S.N.C.C. (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee)." (46)

Martin Luther King claimed that he "hundred of thousands" of students willing to travel to the Deep South to join the protests. The administration decided it had to take action. Robert Kennedy now petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to draft regulations to end racial segregation in bus terminals. The ICC was reluctant but in September 1961 it issued the necessary orders and it went into effect on 1st November. However, James Lawson, one of the Freedom Riders, argued: "We must recognize that we are merely in the prelude to revolution, the beginning, not the end, not even the middle. I do not wish to minimize the gains we have made thus far. But it would be well to recognize that we have been receiving concessions, not real changes. The sit-ins won concessions, not structural changes; the Freedom Rides won great concessions, but not real change." (47)

The FBI and the Freedom Riders

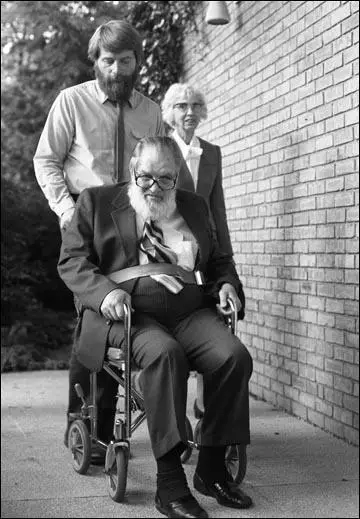

Walter Bergman suffered a severe stroke 10 days after the beating he received in May 1961. He retained most of his speech, but had to learn to write and feed himself again. He never regained the ability to walk and used a wheelchair for the rest of his life. In 1975, Gary Thomas Rowe, an undercover informer for the FBI who joined the Ku Klux Klan, testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee that he had told the agency about the planned attack on the Freedom Riders but that the agency had done nothing to stop it. Rowe's testimony prompted Bergman and his wife to sue the FBI. However, Frances Bergman died in 1979. (48)

Playboy Magazine acquired a confidential 1979 Justice Department 302-page report on Rowe that confirmed that the FBI knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and did nothing to protect them. Nor did he tell Attorney General Robert Kennedy about this information. The Justice Department stated: "it is indeed unfortunate that the bureau did not take additional action to prevent violence, such as notifying the Attorney General and the United States Marshals Service, who might have been able to do something." (49)

This report enabled Freedom Riders to sue the FBI. In 1983, Judge Charles E. Stewart Jr. of Federal District Court in Manhattan ordered the Government to pay $25,000 to James Peck, one of the Freedom Riders who had been badly beaten in Birmingham. (50) Later that year Walter Bergman was awarded $35,000. The estate of Frances Bergman was awarded $15,000. All proceeds were donated to the American Civil Liberties Union. ''The suit righted the essential history of the period,'' said Howard L. Simon, who was executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in Michigan when the suit was tried. ''It proved the Federal Government was not an ally of the civil rights worker, but in fact was in league with local law enforcement and the K.K.K.'' (51)

John Simkin (11th August, 2020)