Walter Bergman

Walter Bergman, the son of a Swedish immigrant farmer, was born in in Youngsville, Pennsylvania, in 1899. He graduated from high school at 15, and attended Greenville College. He joined the United States Army during the First World War and in 1919 he was sent to Germany to help administer the Allied occupation. Seeing the devastation, he became a pacifist. (1)

Bergman returned to a factory job in Youngsville, then began teaching at the local school. He moved to Detroit, where he taught high school classes and studied nights at the University of Michigan to earn a master's degree and then a doctorate in education. He eventually became assistant principal of a elementary school. (2)

In 1929 Bergman became the director of research for Detroit public schools. He recalls he got into trouble for employing Jewish and Black secretaries. "They had a Black man working in the employment office. I decided that I would take him out to lunch. I had gone to a rather modest restaurant fairly regularly for a couple of months, and I had gotten to know everybody on the staff. I took him over there one day, and they served us very pleasantly. I had scarcely gotten back to the office when the restaurant manager walked in. He said, 'Now, didn't I serve you nicely when you and your Black friend were in my restaurant?' I said, 'Yes, you certainly did, and I appreciate that. Of course, that's what I would expect one human being to do for another human being.' He said, 'But please don't do it again!'." (3)

Walter Bergman was a socialist but at first he did support the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, in 1935 he described the New Deal as being too timid in its attack on poverty. He was a founder of both the Michigan chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Michigan Federation of Teachers. He also worked part-time at Wayne State University. (4)

After the Second World War he worked for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the U.S. government's de-Nazification program in Bavaria. In 1948 he returned to the United States to become director of research for the Detroit Board of Education. A victim of McCarthyism, in 1953, the State Department seized his passport while he was teaching at the International People's College in Elsinore, Denmark. After protests by civil liberties groups and education organizations, the passport was restored. (5)

Walter Bergman joins CORE

Bergman and his wife Frances Bergman, were both members of the Socialist Party of America and great admirers of Norman Thomas. He was the first white to join a black Unitarian church, Bergman became increasing active in the political campaigns of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Bergman retired in 1958 and they both became very active in CORE picketing campaigns against segregated hotels, chain stores and swimming pools in Detroit. (6)

In February, 1961, the Bergmans attended a CORE conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (7) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (8)

Walter Bergman and his wife both volunteered mto take part in the Freedom Rides. "Fourteen of us went into training for three days in nonviolent techniques, Gandhi - and Martin Luther King Jr. - type techniques. We had to be absolutely nonviolent, no matter what happened to us. On the last day, the leader, James Farmer, asked, 'Will each of you under all circumstances, no matter what the provocation, refrain from reacting violently?' I was sixty at the time, and it wasn't too difficult for me to say I'd be nonviolent. But there was one young man, a big football player, who said, 'I don't know. If some southern sheriff comes up and tells me that I've got to move along and starts to shove me, I just can't say that I won't shove back.' So James Farmer said, 'Well, we'll have to leave you behind.' That made only thirteen of us, six whites and seven Blacks." (9)

The Bergmans both became passengers on the first bus that left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. He was the oldest of the Freedom Riders. Others on this bus included John Lewis, James Peck, James Farmer, Genevieve Hughes, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person, Herman K. Harris and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (10)

John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman

and James Farmer. Bottom, left to right: Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person,

Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes and Jimmy McDonald.

Susan Herrmann, 20, a student at Fisk University, Nashville, majoring in psychology, later recalled: "We were all prepared to die - and for a while Saturday I thought all 21 of us would die at the hands of that mob in Montgomery. We did not fight back. We do not believe in violence. We were freedom riders... trying to ride in buses through Alabama to New Orleans to help the cause of true freedom for all the races." (11)

Freedom Riders

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They traveled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (12) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (13)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Ku Klux Klan groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and a member of the KKK, reported to his case officer that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. Connor said he wanted the Riders to be beaten until "it looked like a bulldog got a hold of them." It was later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and took no action to prevent the violence. (14)

On 14th May, 1961, a mob of Klansmen, attacked the bus at Anniston, Alabama. Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. One man threw a bomb through a broken window. When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault. (15)

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital." (16)

Attack in Montgomery

The surviving bus traveled to Birmingham, Alabama. When they arrived at the Greyhound Bus Station they saw an angry mob. Gary Thomas Rowe was a member of the KKK who had arrived in the town that day: "We made an astounding sight... men running and walking down the streets of Birmingham on Sunday afternoon carrying chains, sticks, and clubs. Everything was deserted; no police officers were to be seen except one on a street corner. He stepped off and let us go by, and we barged into the bus station and took it over like an army of occupation. There were Klansmen in the waiting room, in the rest rooms, in the parking area." (17)

James Zwerg later recalled: "As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up." (18)

The driver had a brief conversation with the white mob. He returned to the bus with a small group of white people and told the passengers: "We have received word that a bus has been burned to the ground and passengers are being carried to the hospital by the carloads. A mob is waiting for our bus and will do the same to us unless we get these blacks off the front seats." The white men began to try and remove Charles Person and Herman K. Harris from the front seat. Walter Bergman and James Peck attempted to intervene but they were soon knocked to the floor. (19)

Harris later testified that there were "two main guys" kicking Bergman, and that they "just kicked him and kicked, just kicked him... his head and shoulders in the back. I thought maybe they would break his, bust his head." (20) The men adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (21)

The FBI and the Freedom Riders

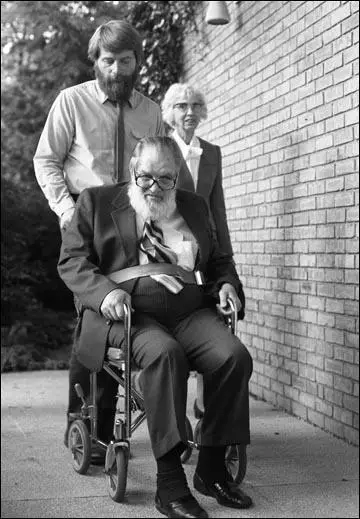

Bergman suffered a severe stroke 10 days after the beating. He retained most of his speech, but had to learn to write and feed himself again. He never regained the ability to walk and used a wheelchair for the rest of his life. In 1975, Gary Thomas Rowe, an undercover informer for the FBI who joined the Ku Klux Klan, testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee that he had told the agency about the planned attack on the Freedom Riders but that the agency had done nothing to stop it. Rowe's testimony prompted Bergman and his wife to sue the FBI. However, Frances Bergman died in 1979. (22)

Playboy Magazine acquired a confidential 1979 Justice Department 302-page report on Rowe that confirmed that the FBI knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and did nothing to protect them. Nor did he tell Attorney General Robert Kennedy about this information. The Justice Department stated: "it is indeed unfortunate that the bureau did not take additional action to prevent violence, such as notifying the Attorney General and the United States Marshals Service, who might have been able to do something." (23)

This report enabled Freedom Riders to sue the FBI. In 1983, Judge Charles E. Stewart Jr. of Federal District Court in Manhattan ordered the Government to pay $25,000 to James Peck, one of the Freedom Riders who had been badly beaten in Birmingham. (24) Later that year Bergman was awarded $35,000. The estate of Frances Bergman was awarded $15,000. All proceeds were donated to the American Civil Liberties Union. ''The suit righted the essential history of the period,'' said Howard L. Simon, who was executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in Michigan when the suit was tried. ''It proved the Federal Government was not an ally of the civil rights worker, but in fact was in league with local law enforcement and the K.K.K.'' (25)

Walter Bergman, aged 100, died on 29th September, 1999, in a nursing home in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Primary Sources

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006)

At sixty-one, Walter Bergman was the oldest of the Freedom Riders, and Frances Bergman, a former elementary school teacher and assistant principal, was the second oldest at fifty-seven. A retired school administrator who had taught part-time at the University of Michigan and Wayne State University, Walter had been a leading figure in the teachers' union movement of the 1930s and 1940s, serving as the first president of the Michigan Federation of Teachers. In the mid and late 1940s, following military service in the European theatre, he spent several years in Germany as a civilian educational specialist, first for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, and later for the U.S. government's de-Nazification program in Bavaria. In 1948 he returned to the United States to become director of research for the Detroit Board of Education.

(2) Walter Bergman, interviewed in Bob Schultz & Ruth Schultz, The Price of Dissent: Testimonies to Political Repression in America (2001)

I had been the director of research in the Detroit public schools for many years. I was considered the oddball there. I was the first person to employ a Jewish secretary. And I had to do it over my boss's objections: "You don't want to do that. She won't get along with the other secretaries. She'll be shunned by everybody." I said, "Now, do I have the right to pick my secretary or not?" "Of course you do." "Well, this is who I want." That was 1929. Later on, I hired the first Black secretary at the board of education. Again I had quite a problem because the other people didn't want me to bring a Black person into the building.

By the late thirties, they had a Black man working in the employment office. I decided that I would take him out to lunch. I had gone to a rather modest restaurant fairly regularly for a couple of months, and I had gotten to know everybody on the staff. I took him over there one day, and they served us very pleasantly. I had scarcely gotten back to the office when the restaurant manager walked in. He said, "Now, didn't I serve you nicely when you and your Black friend were in my restaurant?" I said, "Yes, you certainly did, and I appreciate that. Of course, that's what I would expect one human being to do for another human being." He said, "But please don't do it again!".

After I retired in 1958, I spent a lot of my time working with CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. We did a great deal of picketing to break down segregation. We picked the international headquarters of the Kresge Corporation, which was close to downtown Detroit. We picketed a swimming pool, and some of us got arrested for that. Then in February 1961, CORE had a conference down in Kentucky. My late wife and I both went. While we were there, one of the field secretaries of CORE came back with information about a Supreme Court decision. Not only were interstate buses and coaches open to people regardless of race, but now the public facilities, such as rest rooms and restaurants and waiting rooms were to be open as well. We decided right there, in Lexington, Kentucky, that we would see how far south the Supreme Court's decisions actually did run...

We decided that we we would get a group with the same number of Blacks and whites. Fourteen of us went into training for three days in nonviolent techniques, Gandhi - and Martin Luther King Jr. - type techniques. We had to be absolutely nonviolent, no matter what happened to us. On the last day, the leader, James Farmer, asked, "Will each of you under all circumstances, no matter what the provocation, refrain from reacting violently?" I was sixty at the time, and it wasn't too difficult for me to say I'd be nonviolent. But there was one young man, a big football player, who said, "I don't know. If some southern sheriff comes up and tells me that I've got to move along and starts to shove me, I just can't say that I won't shove back." So James Farmer said, "Well, we'll have to leave you behind." That made only thirteen of us, six whites and seven Blacks.

(3) Paul Maguusson, The Washington Post (5th January, 1977)

A former "freedom rider" crippled after an attack by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama in 1961 filed suit to day in U.S. District Court here against FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley and other top bureau officials who were FBI agents in the South at the time for their alleged failure to stop Klan beatings of civil rights workers.

The Suit, sponsored by the American Civil Liberties Union, seeks $1 million in damages for Walter and Frances Bergman, who were part of a team of seven freedom riders beaten by white vigilantes at a rest stop in Anniston, Ala., May 14, 1961.

Bergman, 77, a former Wayne State University professor and Detroit school board official, and his wife, Frances, 73, were active civil rights workers who volunteered to be among the first to test a 1960 Supreme Court decision intergrating facilities catering to travelers on interstate buses. The beating Bergman suffered left him partially paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair.

The suit stems from testimony given in 1975 by Gary Thomas Rowe, a Klan infiltrator for the FBI, before the Senate intelligence committee that the FBi knew of Klan plans to attack the "freedom riders" but did nothing to stop the violence.

Bergman was knocked to the floor of the bus and kicked repeatedly in the head during a rest stop in Anniston by a mob that also set fire to a second bus, sending several freedom riders to the hospital. no one was ever convicted in connection with the beatings, according to the suit.

A third freedom rider on the Bergman's bus, James Peck, 61, an official with the War Resisters League in New York, has already sued the FBI for $600,000 in damages for the beating he suffered in Montgomery during that same May 14, 1961, ride.

Rowe told the Senate committee that he helped to negotiate an agreement with the Alabama state police and the Montgomery city police that gave Klansmen 15 uninterrupted minutes in Montgomery that day to beat civil rights workers with baseball bats, clubs and chains.

Rowe said his FBI superiors were kept informed of the progress of the negotiations and even sent observers to the bus station in Montgomery to take photographs.

Bergman was not beaten in the Montgomery incident, but his suit claims that the FBI knew that Alabama state police were tracking the bus and would not interfere with violence against its passengers anywhere in Alabama.

The FBI has responded by claiming it had no jurisdiction under federal law to intervene in what should have been a local police matter.

The Bergman's Detroit attorney, William Goodman, said today that he hopes to subpoena FBI Director Kelley, who was agent in charge of the Memphis FBI bureau at the time, and assistant director Richard Held, then in charge of the Mobile, Ala., office both are named in the suit along with Thomas Jenkins an associate director now and then in charge of the Birmingham office.

(4) Court Listener, Bergman v United States (7th February, 1984)

Plaintiffs contend that when Walter Bergman was beaten in Anniston, he suffered an injury to one of the arteries that supply blood to the brain. At trial in October, 1983 on the bifurcated issue of damages, Plaintiffs sought to prove that such an arterial injury, though essentially asymptomatic for several months, caused Dr. Bergman to sustain serious and permanent injury to a portion of his brain when he underwent an appendectomy some four months after the beating. The testimony presented to the Court during the five days of trial on damages focused almost exclusively on this causation question, and its resolution is the most difficult task before the Court at this final stage of the litigation against the United States.

Plaintiffs seek damages for Walter Bergman's permanently disabled condition since the operation, and for the toll that condition took on Frances Bergman during her lifetime. Plaintiffs also claim damages based on the events of the ride itself, including the beating, the fear and emotional injury they both suffered, and the Constitutional deprivations that they endured. Each plaintiff requests an award of one million dollars for these injuries, although they argue that in fact the value of their claims exceeds even that amount...

On May 14, 1961 the Trailways Bus carrying Walter and Frances Bergman, and other freedom riders, stopped in Anniston, Alabama. There, Walter Bergman was beaten into unconsciousness by a group of attackers who entered the bus carrying brass knuckles and clubs. Dr. Bergman recalled being floored by blows to the head and face, but once on the floor of the bus he quickly blacked out. Other witnesses provided details of the severe beating Bergman sustained.

Schooled in nonviolence, Bergman had offered no resistance to the blows, but Isaac Reynolds testified that it "took something for them to beat him down to the floor where they began to kick and stomp him." Herman K. Harris testified that there were "two main guys" kicking Dr. Bergman, and that they "just kicked him and kicked, just kicked him... his head and shoulders in the back. I thought maybe they would break his, bust his head... Another freedom rider, Ivor Moore, ended up on top of Bergman, and he was also kicked and stomped. According to Reynolds, the beatings lasted a total of maybe seven or eight minutes, then Bergman was picked up and thrown over several seats to the rear of the bus. At the time of the incident, Bergman was 61 years old.

When Bergman regained consciousness, he was seated, and the bus was moving on its way to Birmingham. Both of his eyes were blackened from the blows he had received, and his jaw was so sore and swollen that he had to live on a liquid diet for several days. Bergman testified that he felt he had recovered his "normal sensibilities" when he came to. He does not recall feeling dizzy, and he was aware of his surroundings. Over the next few days he had no visual problems, no headaches, suffered no further loss of consciousness, and did not feel faint. He believed his wounds needed only time to heal, and he did not seek medical attention for his injuries.

The freedom riders, unable to continue their bus trip from Birmingham, flew to New Orleans where they stayed for a few days, participating in civil rights activities. The Bergmans then returned to Detroit, Dr. Bergman resuming work he had begun before the trip, on the grounds of their new home. Bergman testified that in April he had cleared a path up a hill from a creek on the property, and that after returning to Detroit he was taking pebbles from the creek bed and using them to cover the path he had already cleared. He testified that the work was fairly strenuous; the hill was steep enough to require five switchbacks, and Bergman was pushing the rocks up the trail in a wheelbarrow. His time that summer was divided between the work on his property and a busy schedule of civil rights activities, including speaking engagements and training events in the midwest and east.

At trial, Dr. Bergman recalled that much later his wife told him that she had noted he had been dragging one of his feet slightly since the beating. The medical records contain reports of this "foot drop" and that Bergman had been acting somewhat "hazy" and had shown some personality change during the summer. It appears that this information came largely from Frances Bergman, although in one notation, a doctor states that "this peculiar demeanor was noticed by the physicians and later confirmed by the patient's wife." A history taken by Dr. Mogill on September 16, 1961 noted that after the beating in Anniston, Bergman "was somewhat dizzy for sometime although there was no apparent sequelae of unusual moment." However, Bergman's present recollection is that he did not suffer any dizziness during the summer of 1961, and he testified that he could not say whether he had in fact been somewhat "hazy" during the months following the beating. The secondhand reports in the medical record are the only evidence before the court of any possible sign during the summer of 1961 that the injury Bergman received in Anniston might be more serious than Bergman had at first believed.

(5) Michael J. Kaufman, The New York Times (4th October, 1998)

Gary Thomas Rowe Jr., 64, a controversial F.B.I. informer who infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan during the civil rights struggles of the 1960's, died of a heart attack four months ago in Savannah, Ga. He was buried under the name of Thomas Neal Moore, the identity that Federal authorities helped him to assume in 1965 after he testified against fellow Klansmen who were accused of killing Viola Gregg Liuzzo, a civil rights volunteer.

Mr. Rowe's death became known last week when a television crew shooting footage for a program about the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Ku Klux Klan searched for Mr. Rowe in Savannah, only to learn that he had died on May 25. Eugene Brooks, who had been Mr. Rowe's lawyer, confirmed the death.

Mr. Brooks said Mr. Rowe had settled in Savannah, his home town, under the Federal witness protection program. The lawyer said Mr. Rowe had worked for a private security company but died bankrupt. Mr. Rowe had long been divorced, the lawyer said, and left five children whose names were not released ''for obvious reasons.''

As an informer and a trial witness, Mr. Rowe provided information that led to the conviction of three Klansmen for the Liuzzo killing. But for the next 18 years, he remained a figure of recurring controversy, accused of, and at times admitting to, planning and participating in the violence he was reporting to the F.B.I.

In 1975, wearing a bizarre cotton hood that resembled a Klan headpiece without the point, he told a Senate committee that the F.B.I. had known of and condoned his participation in violence against black people and had ordered him to sow dissent within the Klan by having sexual relations members' wives.

He admitted to taking part in a baseball bat assault on Freedom Riders in Birmingham in 1961 and told the Alabama police that he had fatally shot a black man, never named, in a riot in 1963 and that Federal authorities knew about these incidents. As late as 1983, Mrs. Liuzzo's children brought an unsuccessful $2 million suit against the F.B.I., charging that through its negligence in recruiting, training and controlling Mr. Rowe, it bore responsibility for the killing.

As Mr. Rowe made his often boastful disclosures, figures inside and outside Government debated the proper use of informers; some demanded greater oversight and others contended that good intelligence could not be obtained if infiltrators had to act like angels or Boy Scouts.

David Garrow, a historian of the civil rights period, learned of Mr. Rowe's death from the television crew when it interviewed him for the program. He passed the information on to The New York Times. Mr. Rowe's story raised three sets of questions, he told The Times. ''The first was to what extent did Rowe like to behave like a thug irrespective of who he was working for? Then there was the question of how much did he or did he not tell the F.B.I., and then, after he went public as an informer, how much did Klansmen and their sympathizers try to offload every unsolved Klan crime on his shoulders?''

Mr. Rowe's name first appeared in public after the killing of Mrs. Liuzzo, a 39-year-old wife of a Detroit teamsters official and mother of four, who had come to Alabama to help in the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march in the spring of 1965. On March 25, the day after the procession, as she drove a young black volunteer home, she was shot to death on a desolate stretch of road.

The next day, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared war on the Ku Klux Klan in an address to the nation and named Mr. Rowe as one of four Klansmen who had been arrested by the F.B.I. in the shooting.

The arrest of the four suspects within 12 hours of the crime suggested that the F.B.I. had inside sources, and when Mr. Rowe was the only one of the four not indicted, he stood revealed as the informer.

In his autobiography, My Undercover Years With the Ku Klux Klan, published in 1976 by Bantam, Mr. Rowe wrote that an F.B.I. agent urged him to join the Ku Klux Klan in 1960 and report on its activities. He became a member of the Klan's Eastview 13 Klavern. F.B.I. records show that he received $20 to $300 a month from the bureau.

In 1965, Mr. Rowe testified in three trials that he had been with the three accused men when they followed and overtook Mrs. Liuzzo's car. When the others fired at her, he said, he pretended to shoot. Despite his testimony and ballistics evidence linking the fatal bullet to a weapon taken from a defendant, the first trial on murder charges in an Alabama court in Lowndes County ended in a hung jury. The second ended in acquittal.

The third trial, in December, was a Federal civil rights case based on an 1870 law. The three defendants were found guilty, each receiving the maximum penalty of 10 years in prison.

Afterward Mr. Rowe vanished into the Federal witness protection program, presumably becoming Thomas Moore. Then in 1975 he emerged, masked in his hood, as a witness before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. He said that in 1961 he had given the F.B.I. advance warning of an attack in which he and other Klansmen participated, beating Freedom Riders with baseball bats, chains and pistols at the Birmingham bus station. He said that the Klansmen had been promised 15 minutes of free rein by the Birmingham police and that he had advised his F.B.I. contacts of this three weeks in advance. He added that when he asked his bureau contacts after the attack why nothing had been done, he said he was told: ''Who were we going to report it to? The Police Department was involved.''

He also testified that the F.B.I. had told him to cause dissension in the Klan. ''I was told to sleep with as many wives as I could, to break up marriages,'' he said.

In 1978, two sets of merging developments brought Mr. Rowe back into the news. The first involved a series of civil actions brought by the Liuzzo children and by several former Freedom Riders who had been injured in the Birmingham attack. They essentially charged the F.B.I. with negligence and failure to protect the rights workers. The second development was a series of accusations by Alabama investigators relying on former Klansmen. Mr. Rowe was indicted in 1978 on murder charges for having shot Mrs. Liuzzo, on the basis of evidence offered by the men he had helped convict in the Federal case 13 years before.

Attempts to extradite Mr. Rowe were blocked, and other efforts by Alabama to prosecute Mr. Rowe were rejected by a Federal judge who ruled that the prosecution was based on highly prejudiced evidence. Earlier Alabama investigators had revealed that they suspected Mr. Rowe of involvement in the 1963 bombing attack on the East 16th Street Baptist Church in which four girls were killed.

In 1980 the Justice Department compiled a 302-page report on accusations involving Mr. Rowe and concluded that the F.B.I. agents knew about and apparently covered up his participation in nonfatal attacks on blacks. But it said there was no evidence in F.B.I. files to support accusations that Mr. Rowe had failed lie detector examinations in which he had denied knowledge of the bombing. Robert E. Chambliss, who in 1977 was convicted of the bombing, had been Mr. Rowe's superior in the Eastview 13 Klavern.

In the 1983 negligence suit filed against the F.B.I. by Mrs. Liuzzo's children, Judge Charles Joiner, a Federal judge in Mrs. Liuzzo's home state of Michigan, ruled that no negligence had been proved.

In another case in 1983, however, Judge Charles E. Stewart Jr. of Federal District Court in Manhattan ordered the Government to pay $25,000 to James Peck, one of the Freedom Riders who had been badly beaten in Birmingham.

In his autobiography Mr. Rowe portrayed himself as a man eager to help the F.B.I. fight the Klan.

Near the end of the book, he said: ''While my ghost was writing the story, an editor remarked that it would make a good book if I 'could demonstrate a complete change of opinion and become a civil rights advocate.' Maybe so but I prefer to let the facts speak for themselves.'' Although he thought black people should be treated fairly, he added, he did not approve of ''integrating schools or churches or neighborhoods or interracial marriage.''

(6) Douglas Martin, The New York Times (10th October, 1999)

Dr. Walter Bergman, an indefatigable civil rights advocate who was savagely beaten by members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1961 as one of the first Freedom Riders and won compensation for the attack from the F.B.I. more than two decades later, died on Sept. 29 in a nursing home in Grand Rapids, Mich., his wife said. He was 100.

He suffered a stroke 10 days after the beating and used a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

In 1983, after an informant for the Federal Bureau of Investigation had testified that the agency had ignored warnings of the impending attack, Dr. Bergman won a damage suit against the Federal Government, though he was awarded only $35,000 of the $2 million he had sought.

''The suit righted the essential history of the period,'' said Howard L. Simon, who was executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in Michigan when the suit was tried. ''It proved the Federal Government was not an ally of the civil rights worker, but in fact was in league with local law enforcement and the K.K.K.''

The attack and its aftermath were emblematic of a life lived at the barricades of social activism. By profession an educator, Dr. Bergman over the years took such controversial stands as declaring in a public debate in 1935 that the New Deal was too timid in its attack on poverty, and that the United Auto Workers was wrong to bar officials from claiming their Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination when asked about Communist leanings. He was a founder of both the Michigan chapter of the A.C.L.U. and the Michigan Federation of Teachers.

In 1953, the State Department seized his passport while he was teaching at the International People's College in Elsinore, Denmark. His wife, Patricia, said the reason was a trip he had made to the Soviet Union to study that country's educational system. After protests by civil liberties groups and education organizations, the passport was quickly restored.

Dr. Bergman, the son of a Swedish immigrant farmer, was the third of three siblings born in Youngsville, Pa. He graduated from high school at 15, and attended Greenville College in Greenville, Ill.

He was drafted into the Army during World War I and served in the Signal Corps, where he learned to fly. The war ended before he could participate in combat, and he was sent to Germany to help administer the Allied occupation. Seeing the devastation, he became a pacifist.

He returned to a factory job in Youngsville, then began teaching in Cherry Creek, N.Y. He moved to Detroit, where he taught high school classes and studied nights at the University of Michigan to earn a master's degree and then a doctorate in education. He rose to research director of the Detroit school system and taught education at the system's universities, which were later merged into Wayne State University.

During World War II, he received conscientious objector status, but later enlisted to participate in what he had come to believe was a moral war against Hitler. He participated in the Normandy landing. After the war he stayed on in Germany to work with the United Nations helping refugees.

On his return home, he continued working for the Detroit schools and universities.

He also continued to act on social and political beliefs. He was the first white to join a black Unitarian church, which then gradually became integrated. He formed a pacifist American Legion post.

When the Congress of Racial Equality began its Freedom Rides, with blacks and whites riding buses through the South to test the efficacy of a Supreme Court ruling that desegregated interstate transportation, he joined up. He and his first wife, Frances, were two of three whites in the first group of 14 to travel to the South, Mr. Simon said. Both were brutally attacked as the bus was parked in Anniston, Ala.

Less than two weeks later, Dr. Bergman suffered a severe stroke. He retained most of his speech, but had to learn to write and feed himself again. He never regained the ability to walk.

In 1975, Gary Thomas Rowe, an undercover informer for the F.B.I. who joined the Klan, testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee that he had told the agency about the planned attack on the Freedom Riders but that the agency had done nothing to stop it.

While testifying, Mr. Rowe wore a cotton hood that resembled a Klan headpiece without the point to protect his identity. He died in 1998, his death initially reported under another name.

Mr. Simon, now the A.C.L.U.'s executive director in Florida, said Mr. Rowe's testimony prompted Dr. Bergman to sue the F.B.I., and he won in 1983. After ruling in Dr. Bergman's favor, Judge Richard A. Enslen of Federal District Court in Kalamazoo, Mich., limited his award to $35,000 because his condition might have resulted in part from an appendectomy he had four months after the beating.

The estate of Frances Bergman, who had died in 1979, was awarded $15,000. All proceeds were donated to the A.C.L.U.

Dr. Bergman remained active in social causes until he entered the nursing home less than two years ago, said his second wife, who, as Patricia Verdier, met him and his first wife at a peace demonstration in 1970. They were married in 1982.

From his first marriage, Dr. Bergman has two surviving daughters, Margaret Dickson of Detroit and Barbara Boyd of Galesburg, Ill., as well as 10 grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and two great-great grandchildren.

Years after he was beaten by Klansmen, Dr. Bergman revisited the Anniston bus station. He noticed four nail holes that had once been used to hold a sign segregating two drinking fountains; now both black and white people were drinking freely from the fountains.

''I had a part in pulling out those nails,'' he said.