Genevieve Hughes

Genevieve Hughes was born into a wealthy family on 14th July, 1932. She grew up in the prosperous Washington suburb of Chevy Chase. She studied at Cornell University and, upon her graduation, moved to New York City to work as a stockbroker at Dunn and Bradstreet. (1)

In the late 1950s Hughes joined Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Members were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. CORE became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America. (2)

According to Raymond Arsenault: "During the late 1950s she became active in the local chapter of CORE, eventually helping to rejuvenate the chapter by co-ordinating a boycott of dime stores affiliated with chains resisting the sit-in movement in the South. Exhilarated by the boycott and increasingly alienated from the conservative complacency of Wall Street, she gravitated toward a commitment to full-time activism, accepting a CORE field secretary position in the fall of 1960. The first woman to serve on CORE's field staff, she made a lasting impression on everyone who met her." (3)

John Lewis later commented that Hughes was "as graceful and gentle as her name," yet "not at all afraid to speak up when she had strong feelings about something." Hughes was once asked why she had joined CORE she replied: "I figured Southern women should be represented to the South and the nation would realize all Southern people don't think alike." (4)

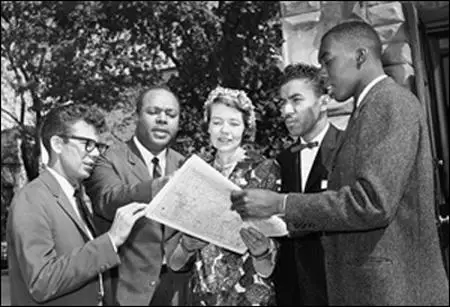

Benjamin Elton Cox and Hank Thomas discussing proposed Freedom Rides

In February, 1961, Hughes attended a CORE conference in Kentucky where the organisation laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (5)

Hughes volunteered to become a passenger on the first bus that left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Others on this bus included John Lewis, James Peck, James Farmer, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person, Herman K. Harris and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (6)

John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman

and James Farmer. Bottom, left to right: Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person,

Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes and Jimmy McDonald.

Susan Herrmann, 20, a student at Fisk University, Nashville, majoring in psychology, later recalled: "We were all prepared to die - and for a while Saturday I thought all 21 of us would die at the hands of that mob in Montgomery. We did not fight back. We do not believe in violence. We were freedom riders... trying to ride in buses through Alabama to New Orleans to help the cause of true freedom for all the races." (7)

Freedom Riders

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They traveled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. Governor John Malcolm Patterson of Alabama who had been swept to victory in 1958 on a stridently white supremacist platform, commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body." (8) In his inaugural address Patterson declared: "I will oppose with every ounce of energy I possess and will use every power at my command to prevent any mixing of white and Negro races in the classrooms of this state." (9)

The Birmingham, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor, organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Ku Klux Klan groups. Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informer, and a member of the KKK, reported to his case officer that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. Connor said he wanted the Riders to be beaten until "it looked like a bulldog got a hold of them." It was later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover knew the plans for the attack on the Freedom Riders in advance and took no action to prevent the violence. (10)

On 14th May, 1961, a mob of Klansmen, attacked the bus at Anniston, Alabama. Some, having just come from church, were dressed in their Sunday best. One man threw a bomb through a broken window. When the Freedom Riders left the bus they were attacked by baseball bats and iron bars. Genevieve Hughes said she would have been killed but an exploding fuel tank convinced the mob that the whole bus was about to explode and the white bomb retreated. Eventually they were rescued by local police but no attempt was made to identify or arrest those responsible for the assault. (11)

James Peck later explained: "When the Greyhound bus pulled into Anniston, it was immediately surrounded by an angry mob armed with iron bars. They set about the vehicle, denting the sides, breaking windows, and slashing tires. Finally, the police arrived and the bus managed to depart. But the mob pursued in cars. Within minutes, the pursuing mob was hitting the bus with iron bars. The rear window was broken and a bomb was hurled inside. All the passengers managed to escape before the bus burst into flames and was totally destroyed. Policemen, who had been standing by, belatedly came on the scene. A couple of them fired into the air. The mob dispersed and the injured were taken to a local hospital." (12)

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that they were taken to the local hospital. "They admitted me into a ward like room not a private room which is what they had in those days and all the black people were kept on gurneys out in in the corridor they were not admitted to the hospital in any formal since nobody had any injuries that I knew of except for smoke inhalation which was fairly serious but more for me because the smoke bomb had been placed in the seat right opposite of mine and I had probably breathed more smoke than anybody else." (12a)

Attack in Montgomery

The surviving bus traveled to Birmingham, Alabama. When they arrived at the Greyhound Bus Station they saw an angry mob. Gary Thomas Rowe was a member of the Ku Klux Klan who had arrived in the town that day: "We made an astounding sight... men running and walking down the streets of Birmingham on Sunday afternoon carrying chains, sticks, and clubs. Everything was deserted; no police officers were to be seen except one on a street corner. He stepped off and let us go by, and we barged into the bus station and took it over like an army of occupation. There were Klansmen in the waiting room, in the rest rooms, in the parking area." (13)

James Zwerg later recalled: "As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up." (14)

The driver had a brief conversation with the white mob. He returned to the bus with a small group of white people and told the passengers: "We have received word that a bus has been burned to the ground and passengers are being carried to the hospital by the carloads. A mob is waiting for our bus and will do the same to us unless we get these blacks off the front seats." The white men began to try and remove Charles Person and Herman K. Harris from the front seat. Walter Bergman and James Peck attempted to intervene but they were soon knocked to the floor. (15)

Harris later testified that there were "two main guys" kicking Bergman, and that they "just kicked him and kicked, just kicked him... his head and shoulders in the back. I thought maybe they would break his, bust his head." (16) The men adhered to Gandhian discipline and refused to fight back and all the men took severe beatings, but this only encouraged their attackers. Walter Bergman was knocked unconscious, and one of the attackers continued to stomp on his chest. Frances Bergman begged the Klansman to stop beating her husband, he ignored her plea. Fortunately, one of the other Klansmen - realizing that the defenceless Freedom Rider was about to be killed - eventually called a halt to the beating. (17)

Another serious attack on the Freedom Riders took place in Montgomery. One member of the mob threw a punch that caught John Lewis in the mouth, Genevieve Hughes and Albert Bigelow attempted to protect Lewis: "More whites surged toward the primitive sounds of violence. Albert Bigelow, next in line behind Lewis, stepped forward to put his body between Lewis and those kicking him. Bigelow's erect posture and determined passivity - such an alien sight in a fistfight - did not keep the attackers from darting in to strike him on the head and body. Three of four thudding blows dropped Bigelow he knocked Genevieve Hughes, the third Freedom Rider in line, sprawling to the floor." (18)

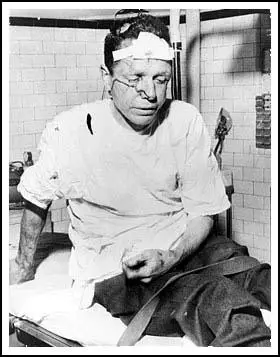

Genevieve Hughes later recalled that it was was James Peck who insisited they continued on the Freedom Ride. "The central figure was Jim Peck and Jim Peck looked like a mummy his head and face were covered with bandages and only his eyes were obvious and his mouth couldn't move and we did have a debate at this occasion about whether to go on. Jim Farmer was not with us. He was back home taking care of a family situation (his father had a serious heart-attack). Jim Peck said we should go on and after that there was not any debate if he couldn't be beaten as he was and still say we should go on we certainly felt we could go on so we all voted unanimously that we would go on and I felt very appalled at seeing Jim Peck but I felt a lot of admiration for him too." (19)

Genevieve Hughes married John Houghton. The marriage ended in divorce. She continued to be active in movements for social justice, environmental protection, and world peace. In 1972, Houghton became a co-founder and first director of the Women's Center in Carbondale, Illinois, one of the first shelters for women victims of domestic violence in the United States. (20)

Genevieve Hughes died of cancer on 2nd October, 2012.

Primary Sources

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006)

Genevieve Hughes... a tall, attractive twenty-eight-year-old white woman, Hughes was a relative newcomer to the movement who had spent most of her life in the prosperous Washington suburb of Chevy Chase. Following her graduation from Cornell, she had moved to New York City to work as a stockbroker at Dunn and Bradstreet. During the late 1950s she became active in the local chapter of CORE, eventually helping to rejuvenate the chapter by co-ordinating a boycott of dime stores affiliated with chains resisting the sit-in movement in the South. Exhilarated by the boycott and increasingly alienated from the conservative complacency of Wall Street, she gravitated toward a commitment to full-time activism, accepting a CORE field secretary position in the fall of 1960. The first woman to serve on CORE's field staff, she made a lasting impression on everyone who met her.

(2) Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 (1988)

One of attackers threw a punch that caught Lewis in the mouth, making the first loud pop of fist against flesh on the Freedom Ride. Lewis sank to the ground. More whites surged toward the primitive sounds of violence. Albert Bigelow, next in line behind Lewis, stepped forward to put his body between Lewis and those kicking him. Bigelow's erect posture and determined passivity - such an alien sight in a fistfight - did not keep the attackers from darting in to strike him on the head and body. Three of four thudding blows dropped Bigelow he knocked Genevieve Hughes, the third Freedom Rider in line, sprawling to the floor.

(3) Genevieve Hughes, interview, American Experience: Freedom Riders (16th May, 2011)

I was on the greyhound bus as I usually was and when we got to Anniston there seemed to be a lot of people out to greet us but I was busy reading my book by Reinhold Niebuhr called Moral Man and Immoral Society. I was being a goody goody but I was also determined to not acknowledge their presence I didn't think it was wise to look them in the eye. It seemed provocative and I simply chose to ignore them so I kept on reading my book. I am not sure I understood a word of what I was reading and after awhile there was some window breaking going on right opposite of where I was sitting and a man who as next to my side the bus reached in his pocket and pulled out a gun and sort of waved it around a little bit. I saw that but again I was trying to see it out of the corner of my eye because I didn't want him to think that he was frightening me which he wasn't at that point there were two men in the back of the bus white in suits and I didn't understand why they were there they weren't part of our group and one of them at least exited I imagine the other one did too although I didn't notice and after a while he shot a gun into the air and the crowd backed off. They had been holding the front door shut... They weren't just screaming. They weren't just banging the bus. I was sitting opposite the window which was broken and a man shoved a bundle of something in which was I realized later burning and it gave off a great deal of small smoke right then and there and I did not know it had the potential of burning up the bus but it obviously was on fire and pretty soon the whole back of the bus was black you couldn't even see in front of your face and I spoke to an innocent passenger who was sitting there and said I'm sorry I got to you into this and he said so am I and Jimmie Robinson yelled something to us like get off the bus and I went forward and he opened a window and he and I both exited and I remember I dropped the book and I hope that it did somebody out there some good becuase I didn't pick it up again... As we left Anniston there was great caravan of cars behind us and they were following us to wherever we were going and it was just a few miles before we pulled over because the tires have been slashed and the bus could not really go any further. It was on its rims...

I knew that we had entered a new phase and it didn't look good for us and fortunately one of these man who I think was a plainclothes policeman fired his gun and he was outside of course at the point that he did that and people who had been holding the door shut so we would all burn up backed away and many people got out through a door and I got out to a window and Jimmie Robertson told me don't panic Genevieve think even at the time I thought that was kind of bizarre it seemed like it was time to panic... I was across the street I believe sitting on the grass but they said that someone had come to pick us up and take us to the hospital or someone being Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth who is one of my heroes and Ed Blankenhein and I got in the back seat and it sounds from the cowardly of us but we lay on the floor so as not to attract attention to ourselves and the fact that we were traveling with Reverend Shuttlesworth and he took us to the hospital. I noticed that back there and in the back of the car that we were in was a baseball bat my thought well this doesn't seem to be in the spirit of non-violence but I didn't have have any occasion to use it. I hope I wouldn't have so we got to the hospital and they admitted me into a ward like room not a private room which is what they had in those days and all the black people were kept on gurneys out in in the corridor they were not admitted to the hospital in any formal since nobody had any injuries that I knew of except for smoke inhalation which was fairly serious but more for me because the smoke bomb had been placed in the seat right opposite of mine and I had probably breathed more smoke than anybody else and the FBI came and interviewed me I couldn't give them any interesting information though... I was having a good bit of trouble breathing and I was coughing up black stuff so I was not otherwise hurt.

Somebody came and informed me that we were leaving and although I was quite interested in staying in bed I got up put my clothes on and went outside the hospital and there was the savior Reverend Shuttlesworth who had come to pick us up and take us away from there and I believe there were a few mobsters around too but they were being quiet and not causing any disturbance at that I can remember so we went and reverend Shuttlesworth's car or someone else... We were lying on the floor and they were chatting up front as if nothing had happened but we did notice a baseball bat back there so I had to think that there were limits to Reverend Shuttlesworth's dedication to nonviolence but I don't think nonviolence came naturally to Reverend Shuttlesworth at all... He was a very brave person in my opinion and not the great orator like Martin Luther King or even James Farmer but person who never gave up always persisted and always in the most unfavorable situations Reverend Shuttlesworth was there. Now he was not a member of CORE he was connected to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and although the two outfits were rivals he didn't let that stand in his way so we were very glad to see Reverend Shuttlesworth.

Well i think we were on the verge of being thrown out of the hospital actually and there were people gathered outside and as usual I don't believe there were any any forces of law and order out there to restrain them so i think in a very real sense he did save us... I can't remember where we met I have a feeling that it was a motel room is but it probably wasn't but the central figure was Jim Peck and Jim Peck looked like a mummy his head and face were covered with bandages and only his eyes were obvious and his mouth couldn't move and we did have a debate at this occasion

about whether to go on. Jim Farmer was not with us. He was back home taking care of a family situation. Jim Peck said we should go on and after that there was no any debate if he couldn't be beaten as he was and still say we should go on we certainly felt we could go on so we all voted unanimously that we would go on and I felt very appalled at seeing Jim Peck but I felt a lot of admiration for him too... In Atlanta Jim Farmer heard that his father was gravely ill and uh he felt he should go back and in fact his father died. we felt a great loss he was definitely the leader and I'm sure he wanted to be there with us so we didn't see him again really until we got to New Orleans.We wanted to take a bus out of Birmingham and continue our trip as planned. And it got to be very frustrating when bus driver after bus driver refused to drive the buses. And so we were stuck there, and God knows, there was no one who was going to come and make the bus drivers drive the buses. In fact, I don’t think you could make them do that. [laugh] So, I don’t know exactly how the decision was made, but we decided we would have to fly out, and we moved over to the airport and spent, I think, six hours there. And no planes would fly out either. So, we were stuck there too. And gradually, the airport began to fill with people, and I knew what was coming. Anybody could have figured that out. And although I hadn’t been afraid the day before, I’d learned to be afraid overnight. And I was very uncomfortable. Gordon Carey arrived from the national office, and Gordon Carey was a strong pacifist. And I said to him, “Aren’t you afraid, Gordon?” And he said, “No.” He wasn’t. And I thought, well, that’s the spirit. So I’m not going to be afraid either, if you’re not afraid.

References

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006) page 99

(2) Juan Williams, Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years (1987) page 148

(3) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006) page 99

(4) John Lewis, Walking with the Wind (1998) page 137

(5) Grand Rapids People's History Project (22nd February, 2016)

(6) Juan Williams, Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years (1987) page 148

(7) Susan Herrmann, Los Angeles Times (22nd May, 2011)

(8) Howard Zinn, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (2014) page 46

(9) Time Magazine (2nd June, 1961)

(10) Harris Wofford, Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties (1980) page 152

(11) David Halberstam, The Children (1998) pages 262-263

(12) James Peck, Freedom Ride (1962) page 125

(12a) Genevieve Hughes, interview, American Experience: Freedom Riders (16th May, 2011)

(13) Gary Thomas Rowe, My Undercover Years with the Ku Klux Klan (1976) pages 40-42

(14) James Zwerg, interview in The People's Century (October, 1996)

(15) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006) page 419

(16) Court Listener, Bergman v United States (7th February, 1984)

(17) Dorothy B. Kaufman, The First Freedom Ride: The Walter Bergman Story (1989) pages 154-155

(18) Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 (1988) page 415

(19) Genevieve Hughes, interview, American Experience: Freedom Riders (16th May, 2011)

(20) The Southern Illinoisan (4th October, 2012)