Benjamin Elton Cox

Benjamin Elton Cox was the born in Whiteville, Tennessee, on 19th June, 1931. He was the seventh of sixteen children. The family moved to Kankakee, Illinois, in 1936. He dropped out of high-school and shined shoes for eighteen months before completing the work for his diploma at the age of twenty. (1)

Cox attended Howard University. It had been established by a charter of the U.S. Congress on 2nd March, 1867. Instigated by the Radical Republicans it was named after General Oliver Howard, an American Civil War hero and a leading figure in the Freeman's Bureau.

Cox spent a year as a visiting student at a seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts and following his ordination in 1958, he became the pastor of the Pilgrim Congregational Church in High Point, North Carolina, a small city fifteen miles southwest of Greensboro. (2)

According to Raymond Arsenault: "In High Point he quickly gained a reputation as a militant civil rights advocate by spearheading local school desegregation efforts, serving as an advisor for the local NAACP Youth Council, and acting as aqn observer for the American Friends Service Committee. Following the early Greensboro sit-ins in February 1960, he encouraged local students to stage their own sit-ins, but only if they were willing to keep them nonviolent." (3)

James Farmer, a senior figure at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the executive director of Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), hired Cox to make speeches in the Deep South on the subject of transport segregation. (4) Cox made a speech where he argued: "I believe we cannot expect to live in a segregated society, be buried by a segregated mortician in a segregated cemetery, and then live eternally in an integrated heaven." (5)

In February, 1961, CORE organized a conference in Kentucky where the organization laid out its plans to have Freedom Riders challenge the racist policies in the south. It was decided they would ride interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. (6) John Lewis, a student at Nashville American Baptist Theological Seminary, commented later: "At this time human dignity is the most important thing in my life. This is the most important decision in my life, to decide to give up all if necessary for the Freedom Ride, that Justice and Freedom might come to the Deep South." (7)

James Farmer and his staff at CORE tried to come up with a reasonably balanced mixture of black and white, young and old, religious and secular, Northern and Southern. The only deliberate imbalance was a lack of women. The CORE leadership was reluctant to expose women, especially black women, to potentially violent confrontations with white supremacists. "Their decision to limit the number of female Freedom Riders to two was undoubtedly rooted in patriarchal conservatism, but they also feared that a balanced contingent of men and women might be interpreted as a provocative pattern of sexual pairing. The situation was dangerous enough, they reasoned, without taunting the segregationists with visions of interracial sex." (8)

Farmer wanted at least one ordained minister to join the Freedom Riders and asked Cox if he would join them. Cox agreed without hesitation. (9) Walter Bergman was another person selected to become a Freedom Rider: "Fourteen of us went into training for three days in nonviolent techniques, Gandhi - and Martin Luther King Jr. - type techniques. We had to be absolutely nonviolent, no matter what happened to us. On the last day, the leader, James Farmer, asked, 'Will each of you under all circumstances, no matter what the provocation, refrain from reacting violently?' I was sixty at the time, and it wasn't too difficult for me to say I'd be nonviolent. But there was one young man (John Moody), a big football player, who said, 'I don't know. If some southern sheriff comes up and tells me that I've got to move along and starts to shove me, I just can't say that I won't shove back.' So James Farmer said, 'Well, we'll have to leave you behind.' That made only thirteen of us, six whites and seven Blacks." (10)

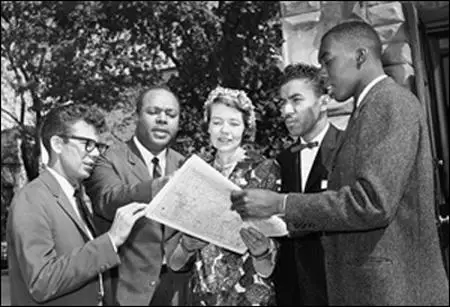

Benjamin Elton Cox and Hank Thomas discussing proposed Freedom Rides

The first bus left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Members of CORE who travelled on the bus included John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes, James Farmer, Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person and Jimmy McDonald. Farmer later recalled: "We were told that the racists, the segregationists, would go to any extent to hold the line on segregation in interstate travel. So when we began the ride I think all of us were prepared for as much violence as could be thrown at us. We were prepared for the possibility of death." (11)

John Lewis, James Peck, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Walter Bergman

and James Farmer. Bottom, left to right: Benjamin Elton Cox, Charles Person,

Frances Bergman, Genevieve Hughes and Jimmy McDonald.

President John F. Kennedy was totally opposed to the Freedom Rides. He called Harris Wofford, the president's Special Assistant for Civil Rights and demanded that he do everything to stop them from taking place: "Kennedy's call to me during the Freedom Rides when he said, without any of his customary humor, 'Stop them! Get your friends off those buses!' He felt that Martin Luther King, James Farmer, Bill Coffin, and company were embarrassing him and the country on the eve of the meeting in Vienna with Khrushchev. He supported every American's right to stand up or sit down for his rights - but not to ride for them in the spring of 1961." (12)

The media was to play an important role in changing the attitudes of the Kennedy administration. On the first bus that left Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi, on 24th May, 1961, the 12 Freedom Riders led by James Lawson, were joined by members of the National Guard and several journalists. The second bus the Freedom Riders were led by John Lewis and the third bus by the Baptist minister, John Lee Copeland. The following day the fourth bus left Montgomery. Those on board included three Baptist ministers, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Wyatt Tee Walker and William Sloane Coffin, chaplain of Yale University. (13)

When the buses arrived at the Jackson Terminal, the Freedom Riders, black and white, went into the white waiting room. Several also used the white rest-room. They were immediately arrested. They refused an offer by NAACP attorneys to post a thousand-dollar bond for each defendant. When the Baptist minister, Ralph Abernathy was asked about Robert Kennedy's complaint that the Freedom Riders were embarrassing the nation in front of the world, he responded: "Well doesn't the Attorney General know we've been embarrassed all our lives?" (14)

Martin Luther King claimed that he "hundred of thousands" of students willing to travel to the Deep South to join the protests. The administration decided it had to take action. Robert Kennedy now petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to draft regulations to end racial segregation in bus terminals. The ICC was reluctant but in September 1961 it issued the necessary orders and it went into effect on 1st November. However, James Lawson, one of the Freedom Riders, argued: "We must recognize that we are merely in the prelude to revolution, the beginning, not the end, not even the middle. I do not wish to minimize the gains we have made thus far. But it would be well to recognize that we have been receiving concessions, not real changes. The sit-ins won concessions, not structural changes; the Freedom Rides won great concessions, but not real change." (15)

In December 1961, Cox went to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and was arrested while leading a peaceful demonstration; in the resulting case, Cox v. Louisiana, the U.S. Supreme Court declared this use of the state's "breach of peace" law unconstitutional. Cox was also instrumental in getting many North Carolina public establishments to integrate, notably McDonald's franchises. Cox's involvement with the civil rights movement resulted in seventeen arrests. He resigned from Congress on Racial Equality in 1965 when he claimed that Black Power advocates such as Stokely Carmichael, came to dominate the organization. (16)

Benjamin Elton Cox died in June 2011.

Primary Sources

(1) Raymond Arsenault, Freedom Riders (2006)

The oldest of the "Southern" Freedom Riders (aside from James Farmer) was the Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox. Though only twenty-nine, he had packed a lot of living - and talking - into three decades of existence. A native of Whiteville, Tennessee, Cox was a loquacious and eloquent preacher who earned the nickname "Beltin' Elton" during the course of the Freedom Rider. The seventh of sixteen children, he moved to Kankakee, Illinois, at the age of five. A high-school dropout, he shined shoes for eighteen months before completing the work for his diploma at the age of twenty. He later attended Livingstone College, an AME Zion institution in Salisbury, North Carolina, before studying for a divinity degree at Howard, and even spent a year as a visiting student at a seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Following his ordination in 1958, he became the pastor of the Pilgrim Congregational Church in High Point, North Carolina, a small city fifteen miles southwest of Greensboro.

(2) Civil Rights Digital Library (2008)

Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox Sr. was born on June 19, 1931, in Whiteville, Tennessee, the seventh of sixteen children. He first participated in civil rights demonstrations at the age of fifteen, protesting outside of a A&W Root Beer drive-in restaurant in Kankakee, Illinois. At the age of sixteen, Cox served as national field secretary for the NAACP, organizing youth chapters. Although Cox dropped out of high school to help his family financially by shining shoes, in 1950 he was able to graduate from Joliet Township High School, an integrated school in Joliet, Illinois. Cox then attended Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina, and graduated in 1954 with a major in sociology and a minor in history. After college, he attended Hood Seminary in Salisbury, but he finished his theological studies in 1957 at the Howard University School of Religion. Cox moved to High Point, North Carolina, to become pastor of Pilgrim Congregational Church, and quickly became active in the community by serving on the High Point School Desegregation Committee in 1959. After the Greensboro Four's sit-in at Woolworth's in 1960, he organized a group of local high school students to participate in the Greensboro demonstrations. In 1961, Cox founded the first Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter in High Point and was hired as the North Carolina Field Secretary. Following a meeting with CORE director James farmer, Cox went to Washington, D.C., for training in nonviolent response to harassment and mistreatment. Cox was one of the thirteen original Freedom Riders in May 1961 and was involved in the Freedom Highways workshop held at Bennett College in July 1962. In December 1961, Cox went to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and was arrested while leading a peaceful demonstration; in the resulting case, Cox v. Louisiana, the U.S. Supreme Court declared this use of the state's "breach of peace" law unconstitutional. Cox was also instrumental in getting many North Carolina public establishments to integrate, notably McDonald's franchises. Cox's involvement with the civil rights movement resulted in seventeen arrests and multiple death threats. He resigned from CORE in 1965 when black power advocates came to dominate the organization, and later moved to Jackson, Tennessee.