On this day on 30th April

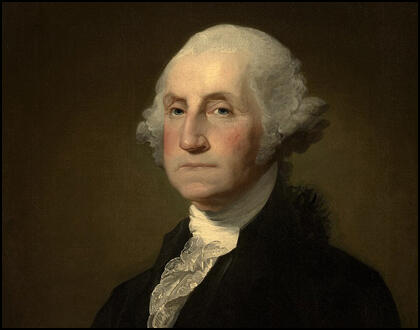

On this day in 1789 George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States. In government Washington worked closely with Thomas Jefferson (Secretary of State) and Alexander Hamilton (Treasury Secretary).

Washington was unanimously reelected in 1792 but by this time the government was not so united and there were serious disagreements between Jefferson's Democratic Republicans and Hamilton's Federalists. Washington tended to favour the Federalists and with the Democratic Republicans gaining increasing support, he decided not to seek a third term and retired from office on 3rd March, 1797.

George Washington was appointed as commander of the United States Army and served in this post until his death on 14th December, 1799.

On this day in 1792, Charles Grey introduces a petition in favour of constitutional reform. He had recently joined with a group of Whigs who supported parliamentary reform to form the Friends of the People. Three peers (Lord Porchester, Lord Lauderdale and Lord Buchan) and twenty-eight Whig MPs joined the group. Other leading members included Richard Sheridan, John Cartwright, Lord John Russell, George Tierney, Thomas Erskine and Samuel Whitbread. The main objective of the the society was to obtain "a more equal representation of the people in Parliament" and "to secure to the people a more frequent exercise of their right of electing their representatives". Charles Fox was opposed to the formation of this group as he feared it would lead to a split in the Whig Party. However, by November eighty-seven branches of the Society of Friends had been established in Britain.

Grey argued that the reform of the parliamentary system would remove public complaints and "restore the tranquillity of the nation". He also stressed that the Friends of the People would not become involved in any activities that would "promote public disturbances". Although Charles Fox had refused to join the Friends of the People, in the debate that followed, he supported Grey's proposals. When the vote was taken, Grey's motion was defeated by 256 to 91 votes.

Some Whig MPs objected to Major John Cartwright being a member of the Friends of the People. They particularly disapproved of a speech Cartwright made where he praised Tom Paine and his book Rights of Man. On 4th June, Lord John Russell and four other Whig MPs resigned from the group in protest against Cartwright's continued membership.

Some Whigs also became concerned with the growing militancy of those advocating parliamentary reform. In January 1792 Thomas Hardy, John Thelwall, and John Horne Tooke had formed the London Corresponding Society. The following year several supporters of parliamentary reform were arrested and tried for sedition. Several of the men, including Thomas Muir, Joseph Gerrald and Maurice Margarot, were sentenced to fourteen years transportation.

On 6th May 1793, Charles Grey once again introduced a parliamentary reform bill. Grey argued that one of the basic principles established by the Glorious Revolution of 1688 was the freedom of elections to the House of Commons. Grey added that "a man ought not to be governed by laws, in the framing of which he had not a voice, either in person or by his representative, and that he ought not to be made to pay any tax to which he should not have consented in the same way." Grey also attacked William Pitt, the Prime Minister, for the way that he exploited the present system. Grey pointed out that Pitt had created 30 new peers who nominated or indirectly influenced the return of a total of 40 MPs.

On this day in 1803 the United States purchases the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million. In 1802 President Thomas Jefferson discovered that Spain had ceded to France the area between the Mississippi Valley and the Rocky Mountains and between Canada and the Gulf of Mexico. Jefferson disliked the idea of Napoleon controlling this area and immediately began negotiations for buying the territory. Needing money to fight a war against Britain and decided to sell the land for $15,000,000. This doubled the area of the United States.

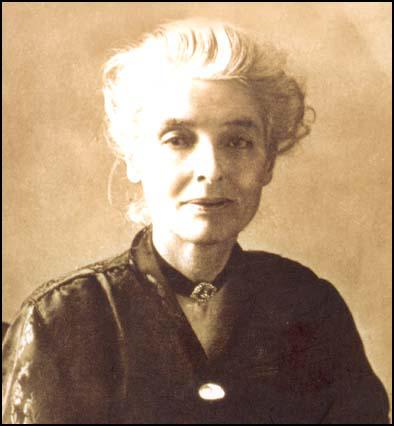

On this day in 1859 Marie Gray, the daughter of George and Eliza Gray, was born in Tunbridge Wells. George Gray was a successful entrepreneur who made a fortune from importing fruit and producing confectionery. Both George and Eliza were ardent Liberals who supported many progressive causes.

In 1881 Marie married the radical lawyer, Charles Corbett, who had an 840-acre estate at Woodgate in the village of Danehill in Sussex. The couple believed they had a responsibility to help the less fortunate members of the community and for many years the couple provided free legal advice for people living in the area.

Her daughter, Margery Corbett Ashby, recalled in her memoirs: "My mother became an energetic cyclist, rebuked by her neighbours for showing inches of extremely pretty feet and ankles; regarded as highly indecorous. It was not only to the ankles that the neighbours objected. My parents were Liberals… at that period as much hated and distrusted by the gentry as Communists are today, and regarded as traitors to their class. In consequence they boycotted them… I suspect this boycott threw my energetic mother even more fervently into good works amongst the villagers, where, in the days before the welfare state, poverty was widespread."

A friend, Mary Hamilton, later commented: "Marie Corbett, was an ardent Feminist, one small external sign being the fact that she regularly wore the breeches she had taken to when bicycling came in, at least a decade before war-time made them permissible. She was a woman of great drive, active in local affairs and local government and all good causes."

Louisa Martindale was another family friend: "My mother became friends with Marie Corbett of Danehill, a remarkable woman who not only threw herself heart and soul into the cause, but also educated her daughters (now Mrs Margery Corbett Ashby and Mrs Cicely Corbett Fisher) to take the leading place they have in public life."

After the passing of the Municipal Franchise Act Marie became a member of the Uckfield Board of Guardians. Later she was the first woman to serve on the Uckfield District Council. Marie also took an active role in national politics and was one of the three women who founded the Liberal Women's Suffrage Society. When attempts to persuade the Liberal Government to introduce measures to give women the vote ended in failure, Marie became active in the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies.

In 1906 General Election Marie's husband, Charles Corbett, became the first Liberal to be elected to represent East Grinstead in the House of Commons. Unlike the Liberal leadership, Corbett strongly supported votes for women and in 1913 helped form the East Grinstead branch of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage.

For many years Marie and her two daughters, Margery Corbett Ashby and Cicely Corbett-Fisher, made public speeches on the subject of women's rights in East Grinstead High Street. East Grinstead was a safe Conservative seat and the crowds were usually very hostile. A survey carried out in 1911 suggested that less than 20% of the women in East Grinstead supported women having the vote in parliamentary elections.

In 1911 Marie Corbett joined with Muriel, Countess de la Warr and Lila Durham to form the East Grinstead Suffrage Society. Membership was always small and meetings rarely attracted more than ten members. She was a strong opponent of the Women Social & Political Union. In March 1912 the East Grinstead Observer published a letter from her that stated: "There cannot be more than a few hundred in all who have put themselves under the leadership of the Social and Political Union for the commission of lawless activities. The members of the East Grinstead Women's Women's Suffrage Society strongly disapprove of acts of violence."

On the 23rd July 1913, Marie organised a public meeting in East Grinstead High Street in preparation for the mass rally at the NUWSS rally at Hyde Park in London on 26th July. The local newspaper claims that over 1,500 people turned up to hear the three main speakers: Marie, Edward Steer, a local politician in favour of women's rights and Laurence Housman, a writer and campaigner for the NUWSS. A group of youths started throwing tomatoes and eggs at the speakers. When the mob began hurling stones at them they were forced to seek sanctuary in a local house. It was only when the mob broke into the building that the watching police intervened.

After the vote was won Marie Corbett concentrated her efforts on reforming the workhouse system and finding homes for orphans. After successfully emptying the Uckfield Workhouse of children Marie turned her attention to other workhouses in the area.

On this day in 1864 Harper's Weekly reports on the Fort Pillow massacre. In April, 1864, General Nathan Forrest and his men captured Fort Pillow in Jackson, Tennessee. The fort contained 262 African American and 295 white soldiers. It was afterwards claimed that most of these soldiers were killed after they surrendered.

Abraham Lincoln condemned the atrocity but refused to agree to the demands of William Seward (Secretary of State), Salmon Chase (Secretary of the Treasury), Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy) and Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War), that an equal number of Confederate prisoners should be executed in an act of revenge.

After the war an official investigation discovered evidence that "the Confederates were guilty of atrocities which included murdering most of the garrison after it surrendered, burying Negro soldiers alive, and setting fire to tents containing Federal wounded." However, Nathan Forrest was never prosecuted for the offence and he went on to become the first Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

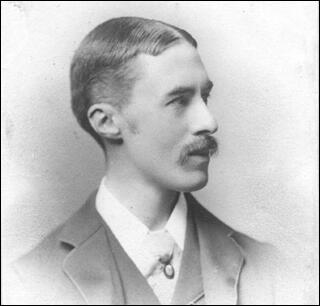

On this day in 1917 Edward Brittain tells Vera Brittain that Geoffrey Thurlow has been killed. "I only heard this morning from Miss Thurlow that Geoffrey was killed in action on April 23rd - a week ago today - and I sent you a cable about noon... Always a splendid friend with a splendid heart and a man who won't be forgotten by you or me however long or short a time we may live. Dear child, there is no more to say; we have lost almost all there was to lose and what have we gained? Truly as you say has patriotism worn very very threadbare."

Thurlow went to the Western Front early in 1916. Soon after arriving at Ypres he was wounded by a shell exploding in the trenches. Vera wrote to Edward Brittain on 23rd February: "I saw that Thurlow had been wounded - I suppose in the recent fighting at Ypres. I have almost loved him since his little letter to me after Roland died, and I can't tell you how anxiously I hope that he is not badly hurt." Thurlow had been shot in the face and he returned to England.

Vera Brittain went to visit him on 27th February. Later that day she wrote to her brother about his condition: "I have just been to see Thurlow at Fishmongers' Hall Hospital, London Bridge. He is only very slightly wounded on the left side of his face; fortunately his eyes, nose and mouth are quite untouched. In fact he says he won't even have a scar left, and the wound is healing with a depressing rapidity.... He was apparently wounded in the bombardment, before all the trench fighting began. He thinks hardly any of his battalion are left now."

Vera told Edward Brittain that Thurlow was suffering from the consequences of serving on the front-line: "Thurlow was... sitting before a gas stove, with a green dressing gown on and a brown blanket over his knees. He seems to feel the cold a great deal, which must be owing to the shock, and also for the same reason his nerves are very bad, so he has been given two months sick leave."

Thurlow told Vera that he was keen to return to France. "Of course he doesn't want to go back a bit, but since he has to go, he's got the same feeling as he had before, that he wants to go out quickly and get it over. He says he finds the anticipation so much worse than the things themselves, whatever they are. He says he is not a bit of a success out there because he is so afraid of being afraid, and he hates the way all his men's eyes are fixed on him when anything big is on, partly to see how he will take it, partly because they are afraid of anything happening to him. He says he objects to war on principle, and is a non-militarist very strongly at heart. I think it was very brave of him to join almost at once as he did... It is easy to see he is suffering from shock; he looks rather a ghost now he is sitting up, talks even more jerkily than before, and works his fingers about nervously while he is talking."

Thurlow returned to the Western Front. On 18th November 1916, he wrote to Vera Brittain: "Since my last letter much has happened - we have been to the war again and the weather treated us abominably: however our battalion did well taking an important Hun trench - we didn't go over the top but had to clean up and hang on to the trench. Luckily we had no officer casualties though there were many among the men. But as our number of officers is at present the irreducible minimum perhaps this accounts for it."

On 27th January 1917 Thurlow wrote to Edward Brittain: "At present we are sitting in a dugout. Brilliant frosty morning: much aerial activity: one Boshe brought down quite near here. A bit of a strafe on during the night and we were so pricelessly warm here that I was positive we should have to stand to or something equally beastly. However we didn't have to so slumbered fitfully on."

Thurlow's mother became very ill in March, 1917, but he was refused leave to see her. He asked Vera: "Don't you often speculate on what lies beyond the gate of death? The after life must be particularly interesting. No chance of getting leave... it is rotten being away from home when anyone isn't well."

On 20th April, 1917, Geoffrey wrote to Vera Brittain that he had heard that Victor Richardson had been badly wounded while fighting at Arras. He knew that he was about to take part in a major offensive himself: "After tea tonight wanting to be alone.... I walked out along a high embankment and everything was fresh and cool quite in contrast to the heated atmosphere of our dugout. As I looked westward I saw just below me in front of the embankment the battered outline of Hun trenches with two long straggling communication trenches winding away into some shell torn trees: the setting sun reflected in the water at the bottom of many crump holes making them look masses of gold... I only hope I don't fail at the critical moment as truly I am a horrible coward: wish I could do well especially for the School's sake."

Geoffrey Thurlow was killed in action at Monchy-le-Preux on 23rd April 1917. Three days later, Captain J. W. Daniel, wrote to Edward Brittain, about Thurlow's death: "The hun had got us held up and the leading battalions of the Brigade had failed to get their objective. The battalion came up in close support through a very heavy barrage, but managed to get into the trench - of which the Boshe still held a part... I sent a message to Geoffrey to push along the trench and find out if possible what was happening on the right. the trench was in a bad condition and rather congested, so he got out on the top. Unfortunately the Boche snipers were very active and he was soon hit through the lungs. Everything was done to make him as comfortable as possible, but he died lying on a stretcher about fifteen minutes later."

On this day in 1936 Alfred Edward Housman died. Housman was born in Frockbury, Worcestershire, on 26th March 1859. Educated at Bromsgrove School, he won a scholarship to St. John's College, Oxford. He became a distinguished classical scholar and in 1892 was appointed professor of Latin at University College, London.

In 1896 he published A Shropshire Lad. The 63 poems recall the innocence, the pleasures and the tragedies of the countryside. He also published critical editions of Manilius (1903) and Juvenal (1905).

In 1911 Housman became Professor of Latin at Cambridge University. His brother, Laurence Housman, was also a successful writer and illustrator.

During the First World War Housman published several poems about the conflict including Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries (1914).

Housman continued to write poetry and his Last Poems (1922) met with great acclaim. Praefanda (1931) was a collection of bawdy and obscene passages from Latin authors.

On this day in 1943 Beatrice Webb died. During the First World War Beatrice served on several government committees. She also wrote several Fabian Society pamphlets such as Labour and the New Social Order (1918), The Wages of Men and Women - Should They be Equal? (1919), Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain (1920) and the Decay of Capitalist Civilization (1923).

In the 1923 General Election Beatrice's husband, Sidney Webb, was chosen to represent the Labour Party in the Seaham constituency. Webb won the seat and when Ramsay MacDonald became Britain's first Labour Prime Minister in 1924, he appointed Webb as his President of the Board of Trade.

Webb left the House of Commons in 1929 when he was granted the title Baron Passfield. Now in the House of Lords, Webb served as Secretary of State for the Colonies in MacDonald's second Labour Government. However, on a point of principle, Beatrice refused to accept the title of Lady Passfield.

In 1932 the Webbs visited the Soviet Union. Although unhappy with the lack of political freedom in the country they were impressed with the rapid improvement in the health and educational services and the changes that had taken place to ensure economic and political equality for women. When they returned to Britain they wrote a book on the economic experiments taking place in the Soviet Union called Soviet Communism: A New Civilization?(1935). In the book the Webbs predicted that "the social and economic system of planned production for community consumption" of the Soviet Union would eventually spread to the rest of the world. They added that they hoped this would happen through reform rather than revolution.

Despite the Stalinist purges and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Webbs continued to support the Soviet economic experiment and in 1942 published The Truth About Soviet Russia (1942).

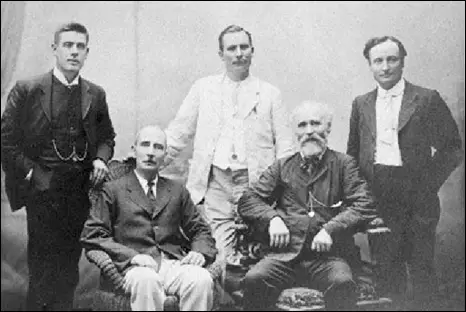

On this day in 1928 social reformer Henry Hyde Champion died in South Yarra. Champion, the son of Major-General J. H. Champion, was born in India on 22nd January, 1859. He attended Marlborough College and after achieving a military commission in the Royal Artillery served with distinction in the Second Afghan War.

In 1881 he returned to England after becoming ill with typhoid. While recovering in PortsmouthHenry Champion read a great deal, including Progress and Poverty by Henry George, the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and several books by John Stuart Mill. These books radicalized Champion and he began to question Britain's foreign policy. In 1882 Champion resigned from the British Army in protest at its Egyptian campaign.

Henry Champion now described himself as a Christian Socialist and in 1882 became editor of the journal, the Christian Socialist. He also joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and showed his commitment by giving the party £2,000. H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the SDF, appointed Champion as editor of the organisation's newspaper, Justice.

In the 1885 General Election, Champion and Hyndman, without consulting their colleagues, accepted £340 from the Conservative Party to run parliamentary candidates in Hampstead and Kensington. The objective being to split the Liberal vote and therefore enabling the Conservative candidate to win. This strategy did not work and the two SDF's candidates only won 59 votes between them. The story leaked out and the political reputation of both men suffered from the idea that they were willing to accept "Tory Gold".

Tom Mann got to know Henry Hyde Champion during this period: "Henry Hyde Champion was about my own age, an ex-artillery officer, a foremost member of the SDF, taking part in all forms of propagandist activity, showing keen sympathy with the unemployed. He had a fine, earnest face, and a serious manner in dealing with the sufferings of the workers. Champion, being a man of vigorous individuality, and genuinely devoted to the movement, could not always wait to get his views as to various forms of propagandist activity endorsed by a committee. He would act upon his own initiative, and commit the organization to plans and projects without consultation. Naturally this would give rise to strong expressions of opinion, frequently of an adverse character, arising from the natural human dislike to being pitch-forked into a project, however excellent, without having any reasonable opportunity for consideration."

In 1886 the Social Democratic Federation became involved in organizing strikes and demonstrations against low wages and unemployment. After one demonstration that led to a riot in London, Champion, H. M. Hyndman and John Burns, were arrested but at their subsequent trial they were all acquitted.

Champion, a Christian Socialist, objected to Hyndman's atheism. He was also concerned by Hyndman's support of violent revolution. Champion's criticisms of Hyndman resulted in him being expelled from the SDF in 1887. He joined the Fabian Society, and although he respected the ideas of George Bernard Shaw and Annie Besant, he was disappointing by their lack of interest in forming a working-class political party.

In 1888 Champion, John Burns and Tom Mann formed the Labour Elector. Edited by Champion, the paper campaigned for the eight-hour day, denounced bad employers and criticised trade union Liberal MPs in the House of Commons. The Labour Elector argued strongly for a new working-class party with strong links to the trade union movement.

As well as writing about industrial disputes, Champion also helped to organize them, and in 1888 joined with Annie Besant and her socialist journal, The Link, to help the Matchgirls Union defeat the Bryant & May company. The following year Champion emerged with Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the leaders of the London Dock Strike. Tillett later recalled: "Our principal Press Officer (during the 1889 Dock Strike) was the socialist journalist, Henry Hyde Champion, one of the founders of the Fabian Society. Although he was in no way officially connected with the strike, he rendered us very valuable help."

Champion had argued for a long time that the British working-class needed a political party that would provide an alternative to the Social Democratic Federation. He therefore fully supported the formation of the Independent Labour Party in 1894. However, trade unionists in the organisation were suspicious of Champion because of his privileged background.

At a conference in Manchester in February 1894, references were made to Champion's involvement with the Conservative Party in the 1884 General Election and delegates suggested that he was not to be trusted. The Times reflected the views of many members: "Champion was an exceedingly able writer and the wielder of a caustic pen. He had, however, the temperament of an aristocrat and an inborn sympathy with Conservative traditions, both of which prevented him from really understanding and sympathizing with the minds of the masses whom he endeavoured to lead."

Champion was so upset by the comments at the conference that he left the Independent Labour Party and emigrated to Australia. Champion settled in Melbourne where he married Elsie Belle Goldstein, the younger sister of the Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein.

Champion suffered a stroke in 1901 which left him semi-paralysed, with his speech affected and a limp, and unable ever again to use his right hand for typing. However, in 1906 he was able to establish the Australasian Authors' Agency, that published the work of aspiring Australian novelists.

Henry Hyde Champion became friends with David Low during the First World War. He later recorded: "Who in 1915 would have identified the mild old gentleman, editor of a tiny literary monthly, walking tremulously with the aid of two sticks in the Melbourne sunshine, with the determined young ex-artillery officer H. H. Champion of the 1880s... No one, I wager. Illness, disappointment and age had long since withdrawn Champion from politics to books. But he retained an interest in justice and right."