On this day on 19th November

On this day in 1600 the future Charles I, the third child and second son of James I and Anne of Denmark, was born in Dunfermline Palace. His brother, Henry, was six years old when he was born. He was created Duke of Albany at his baptism and Duke of York five years later.

Charles was a weak and backward child and remained in Scotland while the rest of the family moved to London. Charles went to live with Alexander Seton, Lord Fyvie, who had nine surviving daughters and a son. In April 1604, Fyvie wrote to the king pointing out that his son was "weak in body" and was having difficulty talking .

It was believed that Charles suffered from rickets and he had difficulty walking without assistance. His doctor stated "he was so weak in his joints and especially ankles, insomuch as many feared they were out of joint". Even so It was now decided that he was strong enough to make the journey to England to be reunited with his family.

After the death of his older brother, Henry, in 1612, Charles was given the title of Prince of Wales and became the heir to the throne. He was educated by a Scottish Presbyterian tutor, and mastered Latin and Greek and showed an aptitude for modern languages. Charles was a shy and reserved boy who never overcame a stammer.

King James came under the influence of Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Charles Howard, Lord of Effingham, who were all sympathetic to the Roman Catholic church. He suggested that Charles should marry Maria Anna, the youngest daughter of King Philip III of Spain. According to John Philipps Kenyon, the author of The Stuarts (1958): "They urged James to marry his son to the daughter of Philip III of Spain and use her huge dowry to pay off his debts, with the ultimate aim of reconciling the English church with Rome."

The English Parliament was actively hostile towards Spain and Catholicism, and when called by James in 1621, the members hoped for an enforcement of recusancy laws, a naval campaign against Spain, and a Protestant marriage for the Prince of Wales. Francis Bacon, the Lord Chancellor, led the campaign against the proposed marriage and along with other MPs suggested that Charles should be married to a Protestant princess. James insisted that the House of Commons be concerned exclusively with domestic affairs and should not be involved in making decisions about foreign policy.

The king's supporters responded by accusing Bacon of bribery and corruption and he was impeached before the House of Lords. Not since the fifteenth century had a great officer of the crown been overthrown in Parliament. Bacon was fined £40,000 and "imprisonment at the king's pleasure". He was also barred from any office or employment in the state and forbidden to sit in parliament or come within the verge (12 miles) of the court. The fine was never collected and his imprisonment in the Tower of London lasted only three days.

James refused to accept defeat and he arranged for Charles to be tutored in Spanish and the latest continental dance steps. In February 1623, he travelled incognito with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, to Madrid, to meet members of the Spanish royal family. He was described as having "grown into a fine gentleman" but it was also observed that he looked undistinguished and was only five feet four inches tall. During this period Charles was strongly influenced by Buckingham's political ideas.

John Morrill has pointed out: "Charles's decision to undertake a personal courtship as a way of breaking through the diplomatic deadlock was an indication of his growing self-confidence. He was now commonly acting as a political agent, meeting with privy councillors, foreign ambassadors, and the duke of Buckingham, sometimes under his father's instructions, sometimes independently. The decision to travel to Spain and conduct face-to-face negotiations to conclude his marriage was a further step in his maturation."

The Spanish negotiators demanded that Charles convert to Roman Catholicism as a condition of the match. They also insisted on toleration of Catholics in England and the repeal of the penal laws. After the marriage Maria Anna would have to stay in Spain until England complied with all the terms of the treaty. Charles knew that Parliament would never accept this deal and he returned to England without a bride.

It was now decided to change foreign policy and James now opened up talks about the possibility of an alliance with Louis XIII of France that involved the marriage of Charles to Henrietta Maria, the king's sister. It was unprecedented for a Catholic princess to be married to a Protestant. Pope Urban VIII only gave his permission when he was assured that the treaty signed in November 1624 included "commitments about religious rights of the queen, her children, and her household; while in a separate secret document Charles promised to suspend operation of the penal laws against Catholics".

In February 1624, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, managed to persuade most members of Parliament to the new anti-Spanish policy and to negotiate a treaty with France. However, it was not explained to Parliament that the proposed marriage would involve increased toleration for Roman Catholics.

These negotiations resulted in Parliament losing confidence in King James. They no longer trusted him and he was forced into making several concessions. This included a Monopoly Act, which forbade royal grants of monopolies to individuals. James also agreed to work closely with Parliament to deal with the economic crisis that the country was experiencing at the time.

Members of the Puritan gentry, John Pym, Denzil Holles and Arthur Haselrig, became the king's main opponents in the House of Commons. Pym eventually emerged as the group's leader. "What made Pym a successful parliamentary politician was his total inner certainty, and the emotional force this gave to his performances. He benefited from a curious incongruity which combined the meticulous attention to unemotional detail of a skilled accountant with the driving passion of a religious enthusiast.... He also enjoyed a considerable intelligence, and an exceptional personal force. All this was backed up by a prodigious capacity for hard work."

James I died on 27th March 1625. Charles married fifteen-year-old Henrietta Maria by proxy at the church door of Notre Dame on 1st May. Charles met her at Dover on 13th June and was described as being small-boned and petite and "being for her age somewhat little". Another source said she was "a gawky adolescent, enormous eyes, bony wrists, projecting teeth and a minimal figure". Caroline M. Hibbard provides a more positive image arguing that she had "brown hair and black eyes and a combination of sweetness and wit remarked on by almost every observer."

Many members of the House of Commons were opposed to the king's marriage to a Roman Catholic, fearing that it would undermine the official establishment of the reformed Church of England. The Puritans were particularly unhappy when they heard that the king had promised that Henrietta Maria would be allowed to practise her religion freely and would have the responsibility for the upbringing of their children until they reached the age of 13. When the king was crowned on 2nd February 1626 at Westminster Abbey, his wife was not at his side as she refused to participate in a Protestant religious ceremony.

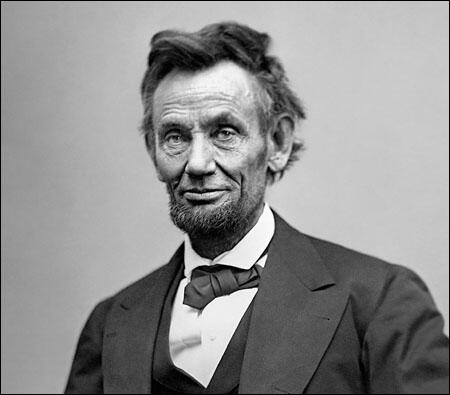

On this day in 1863 President Abraham Lincoln delivers the Gettysburg Address. It included the following:

Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation: conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from this earth.

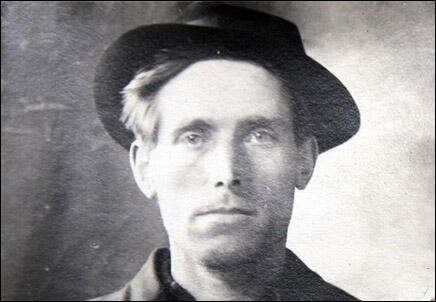

On this day in 1915 Joe Hill, trade union activist is executed. Joel Emmanuel Hägglund was born in Gefle (Gävle), Sweden in 1882. As a child, after the death of his father, in 1887, he worked in a rope factory. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and settled in California where he changed his name to Joe Hill. Converted to socialism in 1910, Hill became a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and was one of the leaders of the San Pedro dock workers' strike. In 1912 he was beaten up and permanently scarred during a free speech campaign in San Diego.

Hill was also a songwriter and his socialist songs appeared in the trade union newspapers, Industrial Worker and Solidarity. After his Red Songbook was published his songs were sung on picket lines and demonstrations. Songs such as The Preacher and the Slave and Casey Jones - The Union Scab became internationally known folk songs.

His biographer, Franklin Rosemont, has pointed out: "Hill contributed to the IWW cause primarily as wordsmith and artist rather than as organizer or soap-boxer. He loved to draw and his cartoons show that he carefully studied the work of such pioneering exemplars of the cartoonist's art as F.B. Opper and Rube Goldberg. He played piano, accordion, guitar, and banjo, and clearly enjoyed the popular music of his day."

George Seldes interviewed Hill and William Haywood in 1912: "When Bill Hayward came to the coal and iron capital of America, Ray Springle and I went to his headquarters, not for news stories, which we knew would never be published, but out of interest in the new labor movement, the Industrial Workers of the World. And so, by chance along with its new leaders we met the ballad-maker of the IWW, Joe Hill." Seldes later recalled: "Joe Hill was a man of great enthusiasm and such easy friendship that in the week or ten days in which we knew him the three of us and another of his friends pledged a lifetime of loyalty to one another."

Hill's trade union activities made him a marked man and unable to find work in California, he moved to Utah. In 1913 Hill helped to organize a successful strike at the United Construction Company. During this dispute Hill stayed with some friends in Salt Lake City. While he was there, John G. Morrison, a former policeman, and his son, Arling, were shot dead by two masked gunman in his grocery shop. A few weeks before the murder, Morrison had told a journalist that he had recently been threatened with a revenge attack because of an incident while he was in the police force.

After the shooting, police discovered two men trying to board a departing train at a railroad station near the store. According to the official report, officers Crosby and Hendrickson had to "empty their guns" to prevent the two men from escaping. The men were taken into custody and identified as C.E. Christensen and Joe Woods, two men with arrest warrants in Prescott, Arizona for robbery.

On the night of the murder, 10th January, 1914, Hill visited a doctor with a bullet wound in his left lung. Hill claimed he had been shot in a quarrel over a woman. Noting that the bullet had gone clean through the body, the doctor reported Hill's visit to the police. They already knew about Hill's trade union activities and decided to arrest him. Hill refused to say how he got the wound. As a witnesses standing outside Morrison's store claimed that he heard one of the murderers say: "Oh, God, I'm shot." Hill was charged with the murder of Morrison and Christensen and Woods were released from custody.

The police chief of San Pedro, who had once held Hill for thirty days on a charge of "vagrancy" because of his efforts to organize longshoremen, wrote to the Salt Lake City police: "I see you have under arrest for murder one Joseph Hillstrom. You have the right man... He is certanly an undesirable citizen. He is somewhat of a musician and writer of songs for the IWW songbook."

Leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World argued that Hill had been framed as a warning to others considering trade union activity. Even William Spry, the Republican governor of Utah admitted that he wanted to use the case to "stop street speaking" and to clear the state of this "lawless elements, whether they be corrupt businessmen, IWW agitators, or whatever name they call themselves"

At Hill's trial in Salt Lake City none of the witnesses were able to identify Hill as one of the murders. This included thirteen-year-old Merlin Morrison, who witnessed the killing of her father and brother. The bullet that hit Hill was not found in the store. Nor was any of Hill's blood. As no money was taken and one of the gunman was heard to say: "We've got you now", the defence argued that it was a revenge killing. However, Hill, who had no previous connection with Morrison, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

Franklin Rosemont has argued: "Nearly all historians have come to recognize as one of the worst travesties of justice in American history. After a trial riddled with biased rulings, suppression of important defense evidence, and other violations of judicial procedure characteristic of cases involving labor radicals, Hill was convicted and sentenced to death."

Bill Haywood and the IWW launched a campaign to halt the execution. Elizabeth Flynn visited Hill in prison and was a leading figure in the attempts to force a retrial. In July, 1915, 30,000 members of Australian IWW sent a resolution calling on Governor William Spry to free Hill. Similar resolutions were passed at trade union meetings in Britain and other European countries. Woodrow Wilson also contacted Spry and asked for a retrial. This was refused and plans were made for Hill's execution by firing-squad on 19th November, 1915.

When he heard the news, Joe Hill sent a message to Bill Haywood saying: "Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time in mourning. Organize." He also asked Haywood to arrange his funeral: "Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don't want to be found dead in Utah." Hill last act before his death was to write the poem, My Last Will.

An estimated 30,000 people attended Hill's funeral. The instructions left in Hill's last poem were carried out: "And let the merry breezes blow/My dust to where some flowers grow/Perhaps some fading flower then/Would come to life and bloom again." Hill's ashes were put into small envelopes and on May Day, 1916, were scattered to the winds in every state of the union. This ceremony also took place in several other countries.

Alfred Hayes wrote a poem about Hill that was later adapted by Earl Robinson and became the famous folk song, I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night. The folk singer, Phil Ochs, wrote and recorded a different, original song called Joe Hill. In 1971 Bo Widerberg wrote and directed the popular Swedish film, Joe Hill.

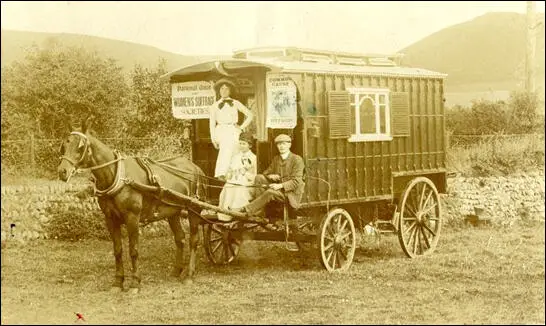

On this day in November 1928 women's suffrage campaigner Helga Gill is killed in a road accident.

Helga Gill, the daughter of Johan Klerk Gill and Karen Marie Ottilia Gill, was born on 9th April, 1885, in Bergen, Norway. She was their oldest of six children. Her mother died in 1900 and as a teenager helped raise her brothers and sisters.

Gill became involved in the campaign to achieve women's suffrage in Norway. In 1907 women who could establish a minimum income of their own and those who are married to a voter, could take part in national elections.

Helga Gill visited England in 1908 and went to live with Charles Corbett, Marie Corbett, Margery Corbett and Cicely Corbett at their home of Woodgate, in Danehill, Sussex. She joined the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Gill toured the country giving talks on how women's suffrage was achieved in Norway.

Helga Gill participated in the Worcester by-election in 1908, speaking to local audiences and putting pressure on candidates to declare whether or not they supported women’s suffrage. The Conservative Party candidate, Edward Goulding, was totally opposed to giving women the vote. The Liberal Party candidate, Harold Elverson, was more sympathetic to the cause, but he was defeated by 4,361 votes to 3,069.

At a meeting at Ampthill in October 1909 she explained why women should have the vote: "She proceeded to show how the classes and masses had one by one claimed their right to vote for their representatives, and how women of all the nation were now alone shut out from this privilege, though they had been striving for over forty years to obtain it. She knew that it was said by many that home was the woman's place, and she agreed with that, but pointed out that home was the place most affected by politics, since, after all, the State was only a collection of homes, and all laws that were passed affected, in some way or other, the individual home."

Gill claimed that women were being exploited. The Bedford Mercury reported: "Miss Gill then called attention to the manner in which women were affecting the labour market. The thousands of women who were compelled by circumstances to earn their own living were being paid at a lower rate of wages than men, and as their labour could be got more cheaply, employers were using them to the detriment of men and of trade. This would not be altered until women could combine to demand attention to their needs, and the surest way of compelling attention was to let them vote, the Members of Parliament would discover that women were a force to be reckoned with and would consider them in their pledges to their constituents."

In 1911 Helga Gill, Cicely Corbett, Marie Corbett, Margery Corbett Ashby, Muriel, Countess de la Warr, Rosalind Gray-Hill (also Secretary of the International Women's Franchise Club), Grace Dykes Spicer and Lila Durham formed the East Grinstead Suffrage Society. In the 1911 Census returns Gill, Gray-Hill and Spicer were all living with the Corbetts at Woodgate, Danehill.

Gill was now employed by the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies as a touring lecturer. At a meeting held in Coventry she attacked the activities of the Women Social & Political Union. The local newspaper, The Coventry Evening Telegraph reported: "The Society she represented was not composed of what were called militant suffragettes… Their side was not reported by the papers, but if they got on the roof of a building and created a scene then the papers would report this.... One questioner asked the lecturer whether she thought the women's suffrage question would have been brought to the front so much as it had if it were not for the militant tactics which had been adopted… Miss Gill said it was a difficult question to answer. Militant tactics had probably brought the question to the front as one of public importance in the Press, but her Society was very much against such methods as had been adopted."

Helga Gill developed into one of the most important NUWSS lecturers. She drove a horse-drawn caravan around the country selling copies of Votes for Women. By 1912 she was appointed as the NUWSS organiser for Oxford, Berkshire, and Buckinghamshire. (8) Gill was sent on a tour of Ireland by the NUWSS to promote women's suffrage. In January 1914 the NUWSS employed her as an organiser at a salary of £120.

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Eveline Haverfield founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Dr. Elsie Inglis, one of the founders of the Scottish Women's Suffrage Federation, suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front. With the financial support of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Inglis formed the Scottish Women's Hospitals Committee. Dr. Elsie Inglis and her Scottish Women's Hospitals Committee sent the first women's medical unit to France three months after the war started. By 1915 the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit had established an Auxiliary Hospital with 200 beds in the 13th century Royaumont Abbey.

Helga Gill volunteered her services and joined the the Scottish Women's Hospital unit as an X-ray operator in Royaumont 50 kilometres from the Front Line. Later she served as an ambulance driver, where she risked her life transporting injured soldiers from the front-line to the Auxiliary Hospital and was often "in danger of being killed by shells." According to her friend Margery Corbett Ashby: "Between the line and the hospital her back wheels were shot away, her driving wheel was splintered between her hands".

After the war Helga returned to live with Marie Corbett and Charles Corbett. Marie was a member of the Uckfield Board of Guardians and often found homes for young children without parents. (16) Helga helped her with this work and adopted one boy, John, who had been born in 1917.

Margery Corbett-Ashby later explained how Helga helped Marie in finding homes for children. "My mother's care and interest for her family of orphans took many forms, and I remember two occasions when much later I was involved in their problems. In the early 1920s news came to me through a friend of a sad case of a young girl of good family, the mother of an illegitimate child, whose parents were ready to take her back home (quite a concession in those days), but not the child. I passed on the news to my mother. My mother asked if she would adopt this baby, and she went home to consult her husband." Charles Corbett pointed out that Marie was now over sixty and only agreed as long as Helga helped her to bring up the child.

In her final years she suffered from heart problems. However she continued to be an active member of the community. "She took immense interest in the Woman's Institute, as its secretary, was leader of the cubs, friend of the ex-Servicemen and of every child.... When one thinks of her it is chiefly her courage, gaiety, and simplicity which stand out. Each person she met was liked entirely on their own individual merits. She totally disregarded such conventions as money or social interest."

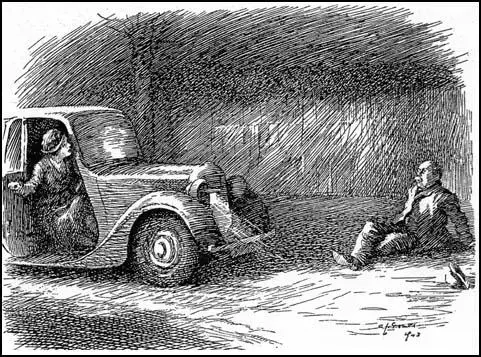

On the 16th November, 1928, Helga Gill picked up her son from school at Forest Row. On the way home to Wych Cross, a large tree was blown down and crashed through the hood of the car. "John Dodd... said he was working at the side of the road, and saw the car approaching from the direction of Wych Cross at a very moderate speed. Just after the car had passed him a large tree fell down. In his opinion the bough of the tree struck the rear part of the car. The car then swerved across the road, into a ditch, up a bank, and came to rest in the front garden of a cottage. On reaching the car witness found Miss Gill hanging half out of the side of the car unconscious."

Helga Gill died of her injuries died 19th November 1928 at the Cottage Hospital, East Grinstead.

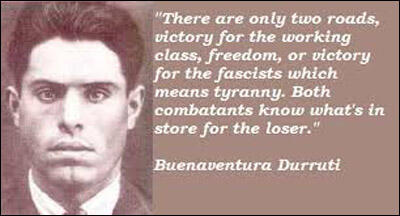

On this day in 1936 anarchist leader, Buenaventura Durruti, is shot. He was born in Spain in 1896. Durruti became a railway worker and as a trade union activist he took part in the General Strike of 1917.

Durruti became an anarchist and with Juan Garcia Oliver and Francisco Ascaso helped establish the Solidarios group in 1919. Two years later members of the group were involved in the murder of Eduardo Dato, the Spanish prime minister. In 1923 the group assassinated Juan Soldevila Romero, the Archbishop of Sargossa, in revenge for the murder by the police of Salvador Segui, a CNT leader.

Durruti and Francisco Ascaso fled to France in June 1923. In protest against the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, Durruti took part in the border raid at Vera del Bidosa on 6th November, 1924. Threatened with extradition to Spain, Durruti moved to Cuba. Constantly on the run, he later lived in Mexico, Chile and Argentina.

Durruti returned to France in 1926. He was arrested but protests by the left resulted in him being released. Durruti now moved to Belgium where he lived until going back to Spain in 1931. He settled in Barcelona where he became involved in organizing strikes. In January 1932 he was arrested and deported to Spanish Guinea.

Durruti returned to Spain but was once again arrested in December 1933 for leading an uprising in Saragossa. In the 1936 Elections Durruti urged anarchists to support the Popular Front in order to defeat the extreme right-wing. After the victory of the Popular Front he joined with Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver to establish communes and workers' committees.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Durruti helped establish the Antifascist Militias Committee in Barcelona. The committee immediately sent Durruti and 3,000 Anarchists to Aragón in an attempt to take the Nationalist held Saragossa.

At the beginning of November, 25,000 Nationalist troops under General Jose Varela had reached the western and southern suburbs of Madrid. Five days later he was joined by General Hugo Sperrle and the Condor Legion. This began the siege of Madrid that was to last for nearly three years.

On 14th November Durruti arrived in Madrid from Aragón with 5,000 men. He immediately went to the frontline where the Manzanares River passed through the University of Madrid. On 19th November, 1936, Durruti was shot by a sniper from one of the upper stories of the Hospital Clinic.

Buenaventura Durruti died the following day. Ethel MacDonald, a British anarchist employed by the CNT-FAI's foreign language information centre, claimed that Durruti had been killed by a member of the Communist Party (PCE).

On this day in 1942 Lord Chief Justice Caldecote criticises Blackout regulations. He said: This order... ran to some thirty-three articles and innumerable sub-paragraphs which everybody concerned with lighting in its various forms is required to understand ... I find it impossible to believe that the regulations could not have been in a simpler and more intelligible form."

To make it difficult for the German bombers, the British government imposed a total blackout during the war. Every person had to make sure that they did not provide any lights that would give clues to the German pilots that they were passing over built-up areas. All householders had to use thick black curtains or blackout paint to stop any light showing through their windows. Shopkeepers not only had to black out their windows, but also had to provide a means for customers to leave and enter their premises without letting any light escape.

Most people had to spend five minutes or more every evening blacking out their homes. "If they left a chink visible from the streets, an impertinent air raid warden or policeman would be knocking at their door, or ringing the bell with its new touch of luminous paint. There was an understandable tendency to neglect skylights and back windows. Having struggled with drawing pins and thick paper, or with heavy black curtains, citizens might contemplate going out after supper - and then reject the idea and settle down for a long read and an early night."

At first lighting restrictions were enforced with improbable severity. On 22nd November 1940, a Naval Reserve officer was fined at Yarmouth for striking matches in a telephone kiosk so that a woman could see the dial. Ernest Walls from Eastbourne was fined for striking a match to light his pipe. In another case a man was arrested because his cigar glowed alternately brighter and dimmer, so that he might be signalling to a German aircraft. A young mother was prosecuted for running into a room, where the baby was having a fit, and turning on the light without first securing the blackout curtains."

No light whatsoever was allowed on the streets. All street lights were turned off. Even the red glow from a cigarette was banned, and a man who struck a match to look for his false teeth was fined ten shillings. Later, permission was given for small torches to be used on the streets, providing the beam was masked by tissue paper and pointed downwards. There were several cases where the courts appeared to act unfairly. George Lovell put up his blackout curtain and then went outside to make sure they were effective. They were not and while he was checking he was arrested and later fined by the courts for breaking blackout regulations. One historian has argued that the blackout "transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war".

Jean Lucey Pratt, who lived in Slough, got into trouble with the authorities for blackout offences: "Not only left light on in bedroom in February but again about four weeks later and the whole performance of policemen climbing in after dark when I was out, to turn out light, was repeated. Excused myself from attending court for first summons and was fined 30 shillings. On the second occasion was charged with breaking blackout regulations and wasting fuel.... I attended court as bidden last Monday morning, quaking. I was expecting to have to pay out £5; at least £3 for the second blackout offence and £2 for the fuel charge. I pleaded guilty, accepted the policeman's evidence and explained in a small voice that I worked from 8.30 to 6 every day, was alone in the cottage, had no domestic help, had to get myself up and off in the morning by 8 o'clock, had not been well and in the early morning rush it was easy to forget the light. The bench went into a huddle and then I heard the chairman saying, '£1for each charge'. £2 in all! I paid promptly."

The blackout caused serious problems for people travelling by motor car. In September 1939 it was announced that the only car sidelights were allowed. The results were alarming. Car accidents increased and the number of people killed on the roads almost doubled. The king's surgeon, Wilfred Trotter, wrote an article for the British Medical Journal where he pointed out that by "frightening the nation into blackout regulations, the Luftwaffe was able to kill 600 British citizens a month without ever taking to the air, at a cost to itself of exactly nothing."

Harold Nicolson wrote about the problem in his diary: "Motor up ... to London. There are few signs of any undue activity beyond a few khaki figures at Staplehurst and some schoolboys filling sandbags at Maidstone. When we get near London we see a row of balloons hanging like black spots in the air. Go down to the House of Commons at 5.30. They have already darkened the building and lowered the lights... I dine at the Beefsteak (Club).... When I leave the Club, I am startled to find a perfectly black city. Nothing could be more dramatic or give one more of a shock than to leave the familiar Beefsteak and to find outside not the glitter of all the sky-signs, but a pall of black velvet."

The Daily Telegraph reported in October, 1939: "Road deaths in Great Britain have more than doubled since the introduction of the black-out, it was revealed by the Ministry of Transport accident figures for September, issued yesterday. Last month 1,130 people were killed, compared with 617 in August and 554 in September last year. Of these, 633 were pedestrians." The Transport Minister Euan Wallace, "made an earnest appeal to all motor-drivers to recognise the need for a general and substantial reduction of speed in blackout conditions."

The government was eventually forced to change the regulations. Dipped headlights were permitted as long as the driver had headlamp covers with three horizontal slits. To help drivers see where they were going in the dark, white lines were painted along the middle of the road. Curb edges and car bumpers were also painted white. To reduce accidents a 20 mph speed limit was imposed on night drivers. Ironically, the first man to be convicted for this offence was driving a hearse. Hand torches, were now allowed, if they were dimmed with a double thickness of white tissue paper and were switched off during elerts.

The cities, without neon signs were utterly transformed after dark. According to Joyce Storey: "The cinema was a bible black bob. No bright neon emblazoned the names of the stars and the feature film revolving round and round in a star-studded endless silver square. These had been extinguished at the onset of the war. There wasn't even the all important grey liveried attendant with the gold braid epaulets on his shoulder shouting on the steps the number of seats available in the balcony. A very full, pleated blackout curtain now draped the great doors at the entrance to the foyer. Once inside their voluptuous folds, you came face to face with a high plywood partition forming a corridor along which the patrons shuffled. A sharp turn to the right at the end of this makeshift entrance led to the dimly lit paybox. So low was the light in that gloom, that it was advisable to have the right amount of money for the ticket; sometimes the keenest eye found it difficult to discern whether the right change had been given."

On this day in 1942 Anne Frank writes in her diary about the persecution of the Jews. She commented: "Dussel has told us a lot about the outside world, which we have missed for so long now. He had very sad news. Countless friends and acquaintances have gone to a terrible fate. Evening after evening the green and grey lorries trundle past. The Germans ring at every door to enquire if there are any Jews living in the house. If there are, then the whole family has to go at once. If they don't find any, they go on to the next house. No one has a chance of evading them unless one goes into hiding. Often they go round with lists, and only ring when they can get a good haul. In the evenings, when it's dark, I often see rows of good, innocent people accompanied by crying children, walking on and on, bullied and knocked about until they almost drop. No one is spared - old people, babies, expectant mothers, the sick - each and all join in the march of death.

On this day in 1942 John Amery makes a radio broadcast from Nazi Germany. He was the son of the Conservative MP, Leo Amery. After finishing his education he went into business but was declared bankrupt in 1936. By this time he had acquired seventy-four convictions for motoring offences. In October 1936 Amery moved to Spain where he worked as a gun-runner for General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. He also served as an intelligence officer with Italian volunteer forces. Amery also met Jacques Doriot the French fascist leader.

After the fascists took control of Spain, Amery and Doriot travelled together to Austria, Czechoslovakia, Italy and Germany before going to live in France. In 1941 Amery was recruited by the Nazis and began making pro Adolf Hitler broadcasts in Berlin. On 19th November, 1942, he stated: "Listeners will wonder what an Englishman is doing on the German radio tonight. You can imagine that before taking this step I hoped that someone better qualified than me would come forward. I dared to believe that some ray of common sense, some appreciation of our priceless civilization would guide the counsels of Mr Churchill's Government. Unfortunately this has not been the case! For two years living in a neutral country I have been able to see through the haze of propaganda to reach something which my conscience tells me is the truth. That is why I come forward tonight without any political label, without any bias, but just simply as an Englishman to say to you: a crime is being committed against civilization. Not only the priceless heritage of our fathers, of our seamen, of our Empire builders is being thrown away in a war that serves no British interests - but our alliance leader Stalin dreams of nothing but the destruction of that heritage of our fathers? Morally this is a stain on our honour, practically it can only lead sooner or later to disaster and Communism in Great Britain, to a disintegration of all the values we cherish most."

In April 1943 John Amery established the Legion of St. George and attempted to persuade British prisoners to fight for Germany against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front. This was embarrassing for Leo Amery who served as secretary of state for India and Burma during the Second World War.

In the final months of the war Amery moved to Italy where he made propaganda speeches on behalf of Benito Mussolini. He also made broadcasts on Italian radio. Amery was captured by Italian partisans in Milan in April 1945, and soon afterwards was handed over to the British authorities.

After being interviewed by MI5 Amery was tried for high treason. On 28th November, 1945, Amery pleaded guilty to eight counts of treason. The Times reported: "Amery, who is 33, was described as a politician. He took the sentence with complete composure. He bowed to Mr. Justice Humphreys when he was brought into Court, and also after sentence had been passed. While the proceedings lasted he appeared most of the time to have half a smile on his face. After sentence had been passed he walked away with bowed head to the cells below the dock. The sudden end of the case was dramatic." It was later claimed that Amery admitted his guilt in order to save his family the pain of a long trial. John Amery was hanged on 19th December, 1945.