On this day on 17th July

On this day in 1883 at a meeting of the National Liberal Federation, to discuss the proposed new Reform Act, the 2,000 delegates passed a resolution that stated that: "any measure for the extension of the suffrage should confer the franchise on women, who, possessing the qualifications which entitle men to vote." (1)

The following year William Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. Gladstone told the House of Commons "that every Reform Bill had improved the House as a Representative Assembly". When opponents of the proposed bill cried "No, no!" Gladstone "insisted that whatever might be the effect on the House from some points of view, it was past doubt that the two Reform Acts had made the House far more adequate to express the wants and wishes of the nation as a whole". He added that when the House of Lords had blocked the Liberal's 1866 Reform Bill the following year "the Conservatives found it absolutely necessary to deal with the question, and so it would be again".

Left-wing members of the Liberal Party, such as James Stuart, urged Gladstone to give the vote to women. Stuart wrote to Gladstone's daughter, Mary Gladstone Drew: "To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God.... No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly."

Millicent Fawcett, on behalf of other female members of the Liberal Party, wrote a letter to Gladstone about this issue: "We write on behalf of more than a hundred women of liberal opinions, whose names we index, who are ready and anxious to take part in a deputation to you, to lay before you their strong conviction of the justice and propriety of granting some representation to women. Believing our own claim to be not only reasonable, but also in strict accord with the principle of your Bill, we are persuaded that if you are able to give any recognition to it, there is no act of your honourable career which will in the future be deemed more consistent with a truly liberal statesmanship."

The following month, Edward Walter Hamilton, Gladstone's private secretary replied. "He (William Gladstone) is most unwilling to cause disappointment to yourself & your friends, whose title to be heard he fully recognises; and he can assure you that the difficulty of complying with a request so referred does not proceed from any want of appreciating the importance of your representation, or of the question itself. His fear is that any attempt to enlarge by material changes the provisions of the Franchise Bill now before Parliament might endanger the whole measure. For this reason, as well as on account of his physical inability at the present time to add to his engagements, he is afraid he must ask to be excused from acceding to your wishes."

A total of 79 Liberal MPs asked Gladstone to recognize the claim of women's householders to the vote. Gladstone replied that if votes for women was included Parliament would reject the proposed bill: "The question with what subjects... we can afford to deal in and by the Franchise Bill is a question in regard to which the undivided responsibility rests with the Government, and cannot be devolved by them upon any section, however respected , of the House of Commons. They have introduced into the Bill as much as, in their opinion, it can safely carry."

Gladstone authorized his Chief Whip to tell Liberal MPs that if the votes-for-women amendment were carried the bill would be dropped and the government would resign. He explained that "I am myself not strongly opposed to every form and degree of the proposal, but I think that if put into the Bill it would give the House of Lords a case for postponing it and I know not how to incur such a risk."

Women in favour of women's suffrage in the party decided to form the Women's Liberal Federation. This group had no success in persuading the male leadership of the Liberal Party in parliament to support legislation. Suffragists within the party doubted the commitment of the leader of the organisation, Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle, to the cause and in 1887 a group of women, including Millicent Fawcett, Eva Maclaren, Frances Balfour and Marie Corbett, formed the Liberal Women's Suffrage Society.

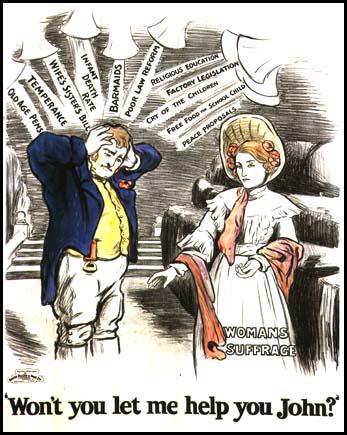

Artists' Suffrage League poster (1909)

On this day in 1918 Tsar Nicholas II and his family and their servants were told to go into the cellar because they feared an attack from the Czech Legion. Soon after they arrived in the cellar they were told they were to be executed. Nicholas, his wife, his son Alexei, his four daughters, and members of his staff were shot. The bodies were wrapped in blankets, loaded on a truck, and driven to a deserted mine shaft several miles outside the city. The bodies were cut up, soaked in benzene and sulphuric acid, and burned. The charred remains were dumped into a swamp some distance from the mine.

Yakov Sverdlov explained what happened to a meeting of the Soviet Council of People's Commissars on 18th July. "I wish to announce that we have received a report that in Ekaterinburg, in accordance with the decision of the regional Soviet, Nicholas has been shot. Nicholas wanted to escape. The Czechoslovaks were approaching the city. The presidium of the Central Executive Committee has decided to approve this act."

The following day published an official announcement of the execution of the former Tsar which stated that "the wife and son of Nicholas Romanov were sent to a safe place." It seems that Lenin took the view that the killing of the Tsarina and her five children would be unacceptable to the Russian public. It would also have been difficult to justify the murder of the Tsar's physician, cook, chambermaid and waiter.

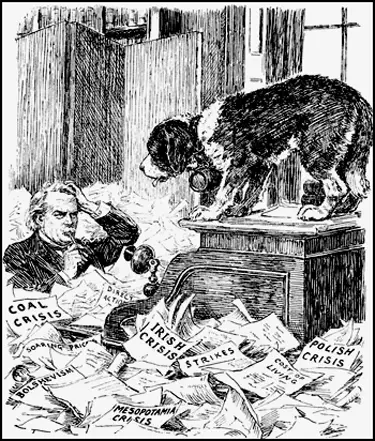

On this day in 1922, Alan Percy, 8th Duke of Northumberland, accuses David Lloyd George of selling honours. "The Prime Minister's party, insignificant in numbers and absolutely penniless four years ago, has, in the course of those four years, amassed an enormous party chest, variously estimated at anything from one to two million pounds. The strange thing about it is that this money has been acquired during a period when there has been a more wholesale distribution of honours than ever before, when less care has been taken with regard to the service of the recipients than ever before and when whole groups of newspapers have been deprived of real independence by the sale of honours and constitute a mere echo of Downing Street from where they are controlled."

Northumberland read out from a letter that suggested that you could obtain a knighthood for £12,000 and a baronetcy for £35,000. "There are only five knighthoods left for the June list. If you decide on a baronetcy, you may have to wait for the Retiring List ... It is not likely that the next government will give so many honours and this is an exceptional opportunity." The letter ended with the comment: "It is unfortunate that Governments must have money, but the party now in power will have to fight Labour and Socialism, which will be an expensive matter."

Northumberland argued that Lloyd George had used the honours system to encourage the newspapers not to criticise him. Lloyd George had in fact ennobled six proprietors during the last few years. Over a period of time the Conservative Party had given honours to all the important press lords. This included Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (The Daily Mail and The Times), Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere (The Daily Mirror), Harry Levy-Lawson, Lord Burnham (The Daily Telegraph) and William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (The Daily Express). As a result, their newspapers continued to criticise Lloyd George.

David Lloyd George responded to the charges made by the Duke of Northumberland by admitting that: "As to the question of bargain and sale, I agree with everything that has been said about that. If it ever existed, it was a discreditable system. It ought never to have existed. If it does exist, it ought to be terminated, and if there were any doubt on that point, every step should be taken to deal with it." But he insisted that making donations to a political party should not exclude the receipt of an honour which was justified if they had been involved in "good works". He announced the setting up of a Royal Commission with a remit to recommend how the honours system could be "insulated from even the suggestion of corruption".

On this day in 1932 Fritz Gerlich publishes an expose of Adolf Hitler in Der Gerade Weg. "Adolf Hitler explains that in his political movement there is only one will and that's his... He never has to explain what he does... his followers have to carry out his commands without any information... The contrast between the real Nordic ideal and the one of Hitler cannot be expressed any more dramatically. Hitler's attitude is absolutely un-Nordic and un-Germanic. It is, racially, pure Mongolian... It is Mongolian absolute despotism that is expressed in Hitler's attitude and that can be explained by the fact that this man is a typical bastard who has mainly non-Nordic blood in his veins."

On 9th March, 1933, Max Amann and Emil Maurice led a gang of stormtroopers into the Gerlich's offices, smashed all the machines and destroyed the contents of desks, files, cupboards and drawers, including the copy for the next issue of the newspaper. Ronald Hayman has suggested that the newspaper planned to carry articles on the death of Geli Raubal and on the Reichstag Fire.

According to Ron Rosenbaum, the author of Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of his Evil (1998): "The nature of the expose he'd been about to publish - some said it concerned the circumstances of the death of Hitler's half-niece Geli Raubal in his apartment, others said it concerned the truth about the February 1933 Reichstag fire or foreign funding of the Nazis - has been effectively lost to history."

Fritz Gerlich was taken to Dachau where he was murdered on 30th June, 1934, the Night of the Long Knives. To notify his wife, they sent her his blood-spattered spectacles. Other Catholics murdered that day included Erich Klausener, the President of the Catholic Action movement and Adalbert Probst, national director of the Catholic Youth Sports Association. Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005) has suggested that "Klausener's murder sent a clear message to Catholics that a revival of independent Catholic political activity would not be tolerated".

On this day in 2005 Edward Heath died of pneumonia.

Edward Heath, the son of a builder, was born in Broadstairs on 9th July, 1916. He studied at Balliol College, Oxford where he was influenced by the political and religious ideas of A. D. Lindsay and William Temple. In 1937 Heath became president of the Oxford Conservative Association.

In 1938 he went with three other undergraduates to observe the Spanish Civil War. He met leaders of the Popular Front government and on his return he campaigned against General Francisco Franco and the Nationalist Army.

As well as being in favour of intervention in Spain Heath was a strong opponent of the appeasement policy of Neville Chamberlain. Although a member of the Conservative Party, Heath supported his university tutor, A. D. Lindsay, the anti-appeasement candidate in the Oxford by-election in October, 1938. The following year he was elected as president of the Oxford Union.

Heath was called up to the British Army in August, 1940. After receiving training at Storrington in Sussex, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery in March 1941 and was posted to the 107 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment based in Chester.

Following the D-Day landings, Heath's regiment arrived in France on 6th July, 1944. Over the next few months he was involved in heavy fighting in Belgium, Netherlands and Germany. He also took part in Operation Veritable, the action to capture the land between the rivers of the Rhine and the Maas. As a result of this action he was awarded the military MBE and was mentioned in dispatches. Heath remained in Germany after the war and attended the Nuremberg Trials in 1946.

A member of the Conservative Party, Heath worked as news editor of the Church Times. In 1948 he went to work for the finance house of Brown, Shipley and Company. In the 1950 General Election Heath won Bexley with a majority of 133. A committed European, Heath made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 26th June in favour of the Schuman Plan. He ended his speech with the words: "It was said long ago in the House that magnanimity in politics is not seldom the truest wisdom. I appeal tonight to the government to follow that dictum, and to go into the Schuman Plan to develop Europe and to coordinate it in the way suggested.

Heath showed that he was on the left of the party with an article in the seminal Conservative pamphlet, One Nation (1950). However, after being appointed as deputy chief whip in 1953 he had to remain silent in the House of Commons.

In 1955 Anthony Eden appointed Heath as his Chief Whip and had the task of persuading Conservative MPs to support the government during the Suez Crisis. Later he served as Minister of Labour (1959-60) under Harold Macmillan.

As Lord Privy Seal he led the British team negotiating entry into the Common Market. A passionate European he was devastated when Charles De Gaulle vetoed Britain's entry in 1963. In the Alec Douglas-Home administration Heath was President of the Board of Trade.

The Labour Party won the 1964 General Election and the following year Heath defeated Enoch Powell and Reginald Maudling to become leader of the Conservative Party. In 1965 Heath supported attempts by Harold Wilson to bring down the white minority regime in in Rhodesia. This upset Conservatives on the right and Heath had to deal with a rebellion led by Lord Salisbury.

Heath lost the 1966 General Election to Harold Wilson. In 1968 Wilson's popularity slumped after Enoch Powell made his "rivers of blood" speech on immigration. Instead of supporting the use of the race issue to gain favour with the British electorate, Heath sacked Powell as a member of the shadow cabinet.

The Conservative Party won the 1970 General Election with a majority of 30 seats. Heath now became prime minister and immediately made the third British application to join the European Economic Community (ECC). On 28th October, 1971, the House of Commons voted with a 112 majority to go into Europe. However, many in his party was unhappy with this policy and it created deep divisions that lasted for over thirty years.

Heath also followed a policy of supporting British industry. In 1971 Rolls-Royce faced bankruptcy and received considerable funds from the government. The Upper Clyde Shipbuilders was also bailed out when it got into economic difficulties.

Heath came into conflict with the trade unions over his attempts to impose a prices and incomes policy. His attempts to legislate against unofficial strikes led to industrial disputes. In 1973 a miners' work-to-rule led to regular power cuts and the imposition of a three day week. Heath called a general election in 1974 on the issue of "who rules". He failed to get a majority and Harold Wilson and the Labour Party were returned to power.

In January 1975 Margaret Thatcher challenged Heath for the leadership of the Conservative Party. On 4th February Thatcher defeated Heath by 130 votes to 119 and became the first woman leader of a major political party. Heath took the defeat badly and refused to serve in Thatcher's shadow cabinet. He considered Thatcher to be a right-wing authoritarian and like another former Conservative prime minister, Harold Macmillan, Heath constantly criticized her policies.

Edward Heath remained in the House of Commons as a backbencher. However, during this period he became an important international statesman and was one of the key members of the Brandt Commission into North/South problems (1977-80), and for several years thereafter was one of the Third World’s most moving advocates. Heath joined the House of Lords in 2001.

On this day in 2009 Walter Cronkite died of complications of dementia on 17th July, 2009.

Walter Cronkite, the son of Walter Leland Cronkite Sr., a dentist, was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, on 4th November 1916. After studying political science and economics at University of Texas (1933-35) he joined The Houston Post.

In 1936 he became a news and sports reporter at KCMO radio in Kansas City. During this period he met an advertising writer named Mary Elizabeth Maxwell. They married in 1941 and over the next few years she gave birth to Walter Leland III, Nancy Elizabeth and Mary Kathleen.

During the Second World War he worked for the United Press. Cronkite was one of the eight war correspondents selected to fly with the United States Air Force on bombing missions over Germany. After a week's high-altitude aircrew training in England he flew his first mission in a B-17 Flying Fortress on 26th February 1943. One of the aircraft, carrying the journalist Robert Post, was shot down and the USAF scheme was abandoned.

Cronkite covered the Nuremberg War Trials and in 1946 moved to the Soviet Union where he worked as the United Press bureau chief in Moscow. Harold Jackson argued: "It was a tough period for western journalists, faced with a Stalinist paranoia which regarded anything not reported by the government-controlled media as a state secret. The physical conditions were also trying and it was with some relief that Cronkite returned to America in 1948." Cronkite then became Washington correspondent for a dozen Midwestern radio stations.

In 1950, Edward Murrow successfully recruited him for CBS. He was assigned to develop the news department of a new CBS station in Washington. He later commented: "We literally figured it out as we went along. For an old newspaperman it was like carrying a printing press around." Cronkite worked on several shows programmes including You Are There. In 1961, Cronkite replaced Murrow as CBS’s senior correspondent, and on 16th April, 1962, he joined CBS Evening News. He later commented: "We literally figured it out as we went along. For an old newspaperman it was like carrying a printing press around."

Cronkite was on air when John F. Kennedy was assassinated. According to the New York Times "Cronkite briefly lost his composure in announcing that the president had been pronounced dead at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. Taking off his black-framed glasses and blinking back tears, he registered the emotions of millions."

In 1968, Cronkite visited Vietnam and returned to do a special program on the war. He called the conflict a stalemate and advocated a negotiated peace. President Lyndon B. Johnson watched the broadcast, and according to Bill Moyers: “The president flipped off the set and said, If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” Douglas Martin claimed that Cronkite "pioneered and then mastered the role of television news anchorman with such plain-spoken grace that he was called the most trusted man in America."

Cronkite retired in 1981 at 64 and was replaced with Dan Rather. Later that year Cronkite was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and four years later was inducted into the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame. CBS named him a special correspondent; the position turned out to be largely honorary, though some reports suggested it paid $1 million a year. Cronkite later argued that this was because it was likely he would overshadow his successor: ""It's not the way I wanted it. I'd love them to make better use of me, but that's internal politics."

Cronkite has written several books including Eve of the World (1971), South by Southeast (1993), North by Northeast (1986), Westwind (1990), Cronkite Remembers (1996), A Reporters Life (1998) and Sailing America's Coast (2008).