On this day on 11th October

On this day in 1521 Pope Leo X titles King Henry VIII of England "Defender of the Faith". Cardinal Thomas Wolsey had suggested to Henry that he might want to distinguish himself from other European princes by showing himself to be erudite as well as a supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. With the help of Wolsey and Thomas More, Henry composed a reply to Martin Luther entitled In Defence of the Seven Sacraments. Pope Leo X was delighted with the document and in 1521 he granted him the title, Defender of the Faith. Luther responded by denouncing Henry as the "king of lies" and a "damnable and rotten worm". As Peter Ackroyd has pointed out: "Henry was never warmly disposed towards Lutherism and, in most respects, remained an orthodox Catholic."

Henry VIII

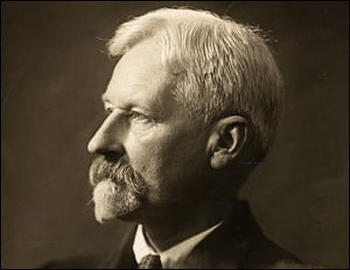

On this day in 1856 Henry Nevinson was born in Leicester. He worked for The Daily Chronicle and reported on the Boer War and 1905 Russian Revolution. Nevinson was a supporter of women's suffrage. His wife, Margaret Nevinson, and his lover, Evelyn Sharp, were both members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). However, in 1906, frustrated by the NUWSS lack of success, they both joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Another journalist, Philip Gibbs pointed out: "Henry W. Nevinson, always the defender of liberty, always a man of fearless courage, allied himself with the women's cause and marched with them when they advanced to the House of Commons, or spoke for them when they held meetings at Caxton Hall. I was at the Albert Hall where the Suffragettes kept up constant interruptions of a big meeting where Cabinet Ministers were present. Nevinson's blood boiled when he saw one of the stewards clench his fist and give a knock-out blow on the chin to one of the militant women. Other women were being roughly handled. Nevinson jumped from the stage box, and fought half a dozen stewards at once until they over-powered him and flung him out."

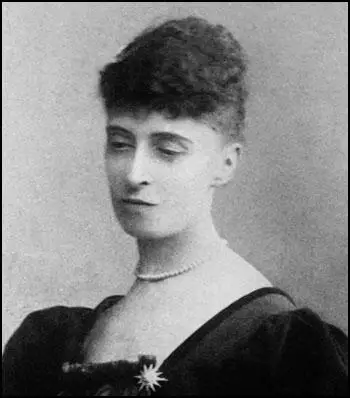

On this day in 1847 Alice Thompson, the daughter of Thomas James and Christiana Weller Thompson was born in Barnes, London. Her sister was the artist, Elizabeth Butler. Her father was a friend of Charles Dickens, and Meynell later suggested that Dickens was romantically interested in her mother,

Alice's first book of poems, Preludes, was published in 1875. Two years later she married the journalist, Wilfrid Meynell (1852-1948). A Roman Catholic, Meynell had eight children between 1879 and 1891.

Alice and her husband co-edited several magazines including The Pen (1880-1881), The Weekly Register (1881-1895) and Merry England (1883-1895). From 1894 she contributed a weekly column to the Pall Mall Gazette. Books by her included The Rhythm of Life (1893), Poems (1893), Holman Hunt (1893), The Colour of Life (1896), The Children (1897), The Spirit of Place (1899) and John Ruskin (1900).

Meynell was a member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies and the Catholic Women's Suffrage Society but was critical of the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union. Maynell wrote: "'A Catholic suffragist woman is a graver suffragist on graver grounds and with weightier reasons than any other suffragist in England.... Surely England has endured too long what is not only immodest but profoundly immoral."

In 1908 the famous playwright, Cicely Hamilton, formed the Women Writers Suffrage League (WWSL). The WWSL stated that its object was "to obtain the vote for women on the same terms as it is or may be granted to men. Its methods are those proper to writers - the use of the pen." Meynell was one of the first women to join the WWSL. Other members included Beatrice Harraden, Elizabeth Robins, Charlotte Despard, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp and Marie Belloc Lowndes.

In later years Meynell concentrated on writing poetry. She was twice considered for the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, on the 1892 death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson and in 1913 to replace Alfred Austin. However, the idea was rejected.

Alice Meynell died on 27th November 1922.

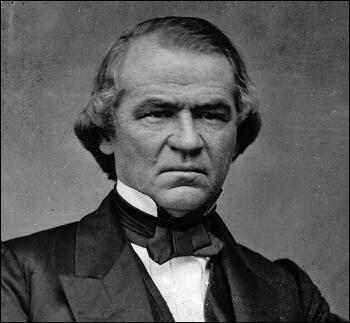

On this day in 1865 President Andrew Johnson paroles Confederate States Vice President Alexander Stephens, a strong supporter of slavery. The Radical Republicans became concerned when Johnson began surrounding himself with advisers such as Preston King, Henry W. Halleck and Winfield S. Hancock, who were well known for their reactionary views. Johnson also began to clash with those cabinet members such as Edwin M. Stanton, William Dennison and James Speed who favoured the granting of black suffrage. In this he was supported by conservatives in the government such as Gideon Welles and and Henry McCulloch.

Johnson now began to argue that African American men should only be given the vote when they were able to pass some type of literacy test. He advised William Sharkey, the governor of Mississippi, that he should only "extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution of the United States in English and write their names, and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at not less than two hundred and fifty dollars."

Johnson became increasingly hostile to the work of General Oliver Howard and the Freeman's Bureau. Established by Congress on 3rd March, 1865, the bureau was designed to protect the interests of former slaves. This included helping them to find new employment and to improve educational and health facilities. In the year that followed the bureau spent $17,000,000 establishing 4,000 schools, 100 hospitals and providing homes and food for former slaves.

In early 1866 Lyman Trumbull introduced proposals to extend the powers of the Freeman's Bureau . When this measure was passed by Congress it was vetoed by Johnson. However, the Radical Republicans were able to gain the support of moderate members of the Republican Party and Johnson's objections were overridden by Congress.

In April 1866, Johnson also vetoed the Civil Rights Bill that was designed to protect freed slaves from Southern Black Codes (laws that placed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations). On 6th April, Johnson's veto was overridden in the Senate by 33 to 15.

On this day in 1872 Emily Wilding Davison was born in London. A member of the Women's Social and Political Union she became involved in its arson campaign and in December 1911 she was arrested for setting fire to pillar-boxes. Davison was convinced that women would not win the vote until the suffragette movement had a martyr. Emily took the decision to draw attention to the suffragette campaign by jumping down an iron staircase. Emily landed on wire-netting, 30 feet below. This prevented her death but she suffered severe spinal injuries.

Once she had recovered her health, Emily Davison began making plans to commit an act that would give the movement maximum publicity. In June, 1913, she attended the most important race of the year, the Derby, with Mary Richardson: "A minute before the race started she raised a paper on her own or some kind of card before her eyes. I was watching her hand. It did not shake. Even when I heard the pounding of the horses' hoofs moving closer I saw she was still smiling. And suddenly she slipped under the rail and ran out into the middle of the racecourse. It was all over so quickly." Davison ran out on the course and attempted to grab the bridle of Anmer, a horse owned by King George V. The horse hit Emily and the impact fractured her skull and she died on 8th June without regaining consciousness.

Among the articles found in her possession were two WSPU flags, a racecard, and a return train ticket to Victoria Station. This has resulted in some historians arguing that she did not intend to kill herself. Sylvia Pankhurst has argued: "Emily Davison and a fellow-militant in whose flat she lived, she had concerted a Derby protest without tragedy - a mere waving of the purple-white-and-green at Tattenham Corner, which, by its suddenness, it was hoped would stop the race. Whether from the first her purpose was more serious, or whether a final impulse altered her resolve, I know not. Her friend declares she would not thus have died without writing a farewell message to her mother." Other research has indicated that Davidson intended to attach a WSPU scarf to the king's horse.

However, Emmeline Pankhurst believed that Davidson wanted to become a martyr. She wrote in her biography, My Own Story (1914): "Emily Davison clung to her conviction that one great tragedy, the deliberate throwing into the breach of a human life, would put an end to the intolerable torture of women. And so she threw herself at the King's horse, in full view of the King and Queen and a great multitude of their Majesties' subjects."

The historian, Martin Pugh, believes it is impossible to know if she intended to commit suicide: "Davison's detachment from the formal organisation complicates the task of explaining her motives... As a result no contemporary really knew whether Davison intended suicide. The evidence is inconclusive... Admittedly on two occasions she had thrown herself over the railings in Holloway prison (which were designed to prevent suicides) and she is on record as telling the prison doctor in June 1912 that 'a tragedy is wanted'. But what did that mean? Contemporary medical evidence commonly regarded women, and suffragettes in particular, as prone to hysteria and thus as suicidal."

On this day in 1874 Mary Heaton, was born in New York City. Her mother had inherited a large fortune from her first husband, a wealthy shipping magnate. Soon after his death she remarried Mary's father, Hiram Heaton. The family lived in a 24-room house in Amherst, Massachusetts. Mary travelled extensively and as a child she learnt to speak fluent French, Italian and German.

In 1896, Mary Heaton began to study at the Art Students' League, located on West 57th Street in New York City. It had no entrance requirements and no set course. By the time Heaton joined it had developed a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. Heaton became friendly with several students such as May Wilson Preston, Alice Beach Winter, Ida Proper and Lou Rogers who became active in the struggle for women's suffrage and other progressive causes. However, Heaton lacked artistic talent and she wrote in her diary: "When I come into my room and see my work lying around, my sense of my own futility overwhelms me. After so much work, that is all I can do."

In 1898 Mary Heaton married the journalist, Albert Vorse. With her husband's encouragement she concerntrated on writing rather than painting. The couple moved to Provincetown in 1906, where she gave birth to a son. Mary Heaton Vorse published her first book, The Breaking-In of a Yachtsman's Wife, in 1908. This was followed by Autobiography of an Elderly Woman (1910) and Stories of the Very Little Person (1910).

Albert Vorse died in 1910 and she married the radical journalist, Joseph O'Brien, two years later. Mary became increasingly involved in politics and after becoming a close friend of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and wrote a sympathetic account of the Lawrence Textile Strike in 1912. As Linda Ben-Zvi pointed out: "The couple shared a passionate interest in labor movements and suffrage causes, as well as a great love for Provincetown and the Vorse house, which O'Brien made his own, remodeling and expanding it to accommodate Mary's two children from her first marriage and Joel, born to them in the winter of 1914. Joe was big, friendly, and easy going. His Irish humor particularly appealed to Susan, and she relished his friendship as she did his stories and yarns."

Mary Heaton Vorse became a widow for a second time in 1915. Later that year she joined with a group of left-wing writers, including Floyd Dell, George Gig Cook, John Reed, Louise Bryant, Susan Glaspell, Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay to establish the Provincetown Theatre Group.

Vorse was strong supporter of women's suffrage and was involved in the suffrage campaign in the United States. On the outbreak of the First World War, Vorse and other pacifists in the country, began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. Jane Addams was elected chairman and other women involved in the organization included Mary McDowell, Florence Kelley, Alice Hamilton, Anna Howard Shaw, Belle La Follette, Fanny Garrison Villard, Emily Balch, Jeanette Rankin, Lillian Wald, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Crystal Eastman, Carrie Chapman Catt and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Jane Addams was asked to chair the meeting and Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Julia Lathrop, Leonora O'Reilly, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Emily Bach went as delegates from the United States. Others who went to the Hague included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, (England); Chrystal Macmillan (Scotland) and Rosika Schwimmer (Hungary). Afterwards, Jacobs, Addams, Macmillan, Schwimmer and Balch went to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome, Berne and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe.

Mary Heaton Vorse continued her work for the radical journal, The Masses, until it was forced to close because of its opposition to the First World War. Over the next few years she produced articles on child labour, infant mortality, labour disputes and working class housing for several newspapers including New York Post and New York World.

In 1920 Mary Heaton Vorse began living with Robert Minor, a talented cartoonist and founding member of the American Communist Party. She suffered a miscarriage in 1922 and soon afterwards Minor left her for illustrator Lydia Gibson. The couple got married in 1923. As a result of the trauma of these two events, Mary became addicted to alcohol. However, she broke the habit in 1926 and she returned to writing.

As well as publishing eighteen books, A Footnote to Folly (1935), Labor's New Millions (1938) and Time and the Town (1942), Vorse published more than 400 articles and stories in most of America's leading journals, such as McClure's Magazine, Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker, Harper's Weekly, New Republic and Ladies' Home Journal.

Mary Heaton Vorse died aged 92, on 14th June, 1966 at her home in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

On this day in 1884 Eleanor Roosevelt was born in New York City. In 1905 she married her cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Like her husband, Eleanor was a Democrat and took a strong interest in politics. However, she was far more left-wing than her husband. Eleanor worked for the League of Women's Voters, the National Consumer's League and the Women's Trade Union League. She also became friendly with the African American educator, Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White, the national secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). These friendships resulted in Eleanor taking a close interest in African American civil rights.

In 1935 Eleanor attempted to persuade Franklin D. Roosevelt to support and Anti-Lynching bill that had been introduced into Congress. However, Roosevelt refused to speak out in favour of the bill that would punish sheriffs who failed to protect their prisoners from lynch mobs. He argued that the white voters in the South would never forgive him if he supported the bill and he would therefore lose the next election.

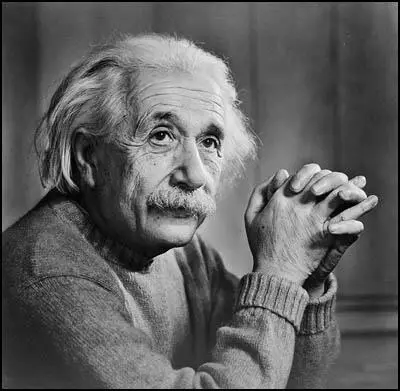

On this day in 1939 Albert Einstein informs President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the possibilities of an atomic bomb.

On this day in 1940 Philip Zec publishes cartoon in The Daily Mirror on Operation Sealion.

On this day in 1945 Chinese civil war begins between Kuomintang government led by Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong's Communist Party.

On this day in 1946 Fritz Saukel was executed for war crimes. Saukel joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) in 1921 and when Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933 he appointed him as Governor of Thuringia. In March 1942 Martin Bormann arranged for him to become Reich Director of Labour and was responsible for meeting the demands of Albert Speer at the ministry of armaments. Over the next three years Saukel's teams went out on the streets to recruit over seven million foreign workers. At the end of the war Saukel was captured by Allied troops. At the the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial he claimed he had not known about the concentration camps. Fritz Saukel was found guilty of crimes against humanity and was executed.