On this day on 11th April

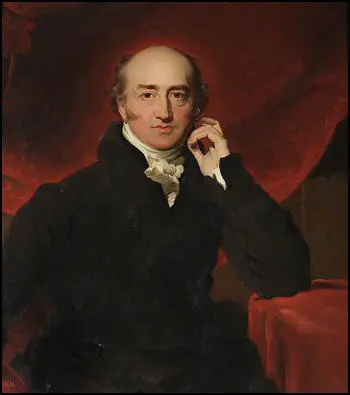

On this day in 1770 George Canning was born in London. George's father died when he was one year old leaving the family in poor financial circumstances. George was helped by his mother's brother, who paid for him to be educated at Eton College. A star pupil, George went to Christ Church, Oxford before becoming a lawyer in 1790.

George Canning's uncle, a reformer, arranged for him to meet leading Whig politicians such as Charles Fox. After a period under the influence of Fox, George Canning met the Tory, William Pitt. The two men became friends and in 1793 Pitt helped Canning become MP for the rotten borough of Newtown in the House of Commons.

In 1796 William Pitt appointed Canning as secretary of state for Foreign Affairs. This was the first of a series of posts held under Pitt that included: commissioner of the board of control (1799-1800), paymaster-general (1800-1801) and treasurer of the navy (1801). After Pitt resigned in 1801, Canning joined the opposition to Henry Addington's government. Over the next few years Henry Addington suffered from Canning's parliamentary attacks. Canning was especially critical of Addington's refusal to accept Catholic Emancipation.

In May 1804 William Pitt returned to power and Canning was once again given the post of treasurer of the navy. After Pitt's death in 1806, Canning became foreign minister in the Duke of Portland's government. Canning played an important role in planning the war against France. It was Canning's idea to seize the Danish Fleet. This severely weakened Napoleon's forces and was a a contributing factor to his eventually defeat. Canning promised to send more troops to the Duke of Wellington who was fighting in Portugal. Canning was furious when he discovered that the secretary of war, Lord Castlereagh, sent the troops to Holland instead. A bitter argument took place and eventually Castlereagh challenged Canning to a duel on Putney Heath on 21st September, 1809. The two men missed with their first shots but eventually Castlereagh wounded Canning in the thigh.

George Canning left government and for the next few years Canning concentrated on writing. He contributed to the Anti-Jacobin Review and with Sir Water Scott helped to establish the Quarterly Review. Canning contributed several articles on political subjects including the need for full political and religious rights for Catholics. However, Canning was a strong opponent of any increase in the number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections.

In 1812 Canning became MP for Liverpool. Canning was invited by the new prime minister, Lord Liverpool, to become foreign minister. Canning refused office because he was unwilling to serve in the same government as Lord Castlereagh. Liverpool approached Canning on several occasions to join his government and eventually he changed his mind and in 1816 became president of the board of control. After Castlereagh committed suicide in 1822, Canning replaced him as foreign minister. George Canning held the post of foreign minister for the next five years.

When Lord Liverpool resigned in 1827 King George IV interviewed Robert Peel, the Duke of Wellington and George Canning for the post of prime minister. When the king appointed Canning, Wellington, Peel and several other leading Tories resigned from the government. Canning was forced to rely on the support of the Whigs to hold on to power. Those Whigs who accepted government posts had to promise not to raise the issue of parliamentary reform.

George Canning first concern was to tackle the problem of the Corn Laws. On 1st March, 1827, Canning introduced the proposal that foreign wheat should be admitted at a 20s. duty when the price had fallen to 60s. This new sliding scale enabled the duty to fall as the price rose, and to rise as the price fell. The Duke of Wellington led the fight against this measure and although passed by the House of Commons, it was defeated in the House of Lords.

Even before being appointed prime minister, George Canning's health was in decline. The strain of office made matters worse and on 29th July he informed George IV that he was seriously ill. Canning was taken to the home of the Duke of Devonshire and on 8th August, 1827, he died in the same room in which, twenty-one years before, his first political influence, Charles Fox, had passed away.

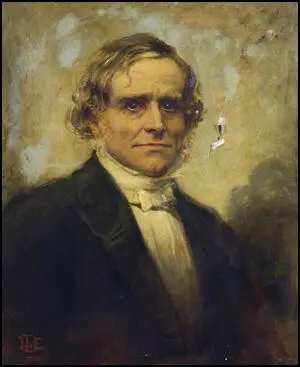

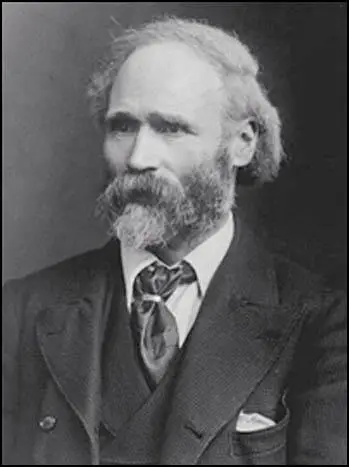

On this day in 1825 Ferdinand Lassalle, the son of a successful silk merchant, was born in Wrocław, Silesia, on 11th April 1825. He studied philosophy in Berlin and he became a strong supporter of Georg Hegel.

After graduating in 1845 Lassalle moved to Paris. On his return to Germany he became friends with Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt. At the time she was involved in a protracted legal case against her husband. Lassalle provided her with valuable support and when she won the case she paid him an annual income for the rest of his life.

Lassalle held strong political views and he became involved in the German Revolutions of 1848. Lassalle was eventually arrested and charged with inciting armed opposition to the state and resistance against public officials. Found guilty of the second charge he was sentenced to six months in prison. On his release he was deported from Germany.

With the help of Alexander von Humboldt Lassalle was given permission to live in Berlin in 1859. In return, he promised not to be active in politics. Over the next few years he wrote several books on legal matters. This included The System of Acquired Rights (1861). However, a pamphlet he published in 1862 was seized by the authorities. He was arrested and was briefly imprisoned in 1863.

Eduard Bernstein argued that at this time: "Lassalle was in his thirty-seventh year, in the full force of his physical and mental development. He had already lived a strenuous life; he had made himself a name politically and scientifically – both, it is true, within certain limited circles; he was in relations with the most prominent representatives of literature and art; he had ample means and influential friends. In a word, according to ordinary notions, the Committee, composed of hitherto quite unknown men, representing a still embryonic movement, could offer him nothing he did not already possess. Nevertheless, he entered into their wishes with the utmost readiness, and took the initial steps for giving the movement that direction which best accorded with his own views and aims."

Lassalle joined the Communist League, where he met fellow members, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Wilhelm Liebknecht. Lassalle wrote several pamphlets that attempted to popularize the ideas of Marx. One of his converts was August Bebel, the future leader of the socialist movement. He wrote in his autobiography: "The open letter of Lassalle did not make at all such apt impression upon the world of labor as had been expected, in the first place, by Lassalle himself; in the second place, by the small circle of his followers. For my part, I distributed about two dozen copies in the Industrial Educational Club, in order to give the other side a chance. That the letter should have made so little impression upon the majority of the laborers in the movement of that time, may seem inexplicable today to some people. But it was quite natural. Not merely the economic, but also the political conditions were still very backward."

Karl Marx was highly critical of Lassalle's interpretation of his work. He also disapproved of Lassalle when he established the General German Workers' Association (ADAV) in May, 1863. The main objective of the organisation was to win universal suffrage through peaceful and legal means. As a result, most members of the Communist League refused to join the organisation.

Élie Halévy argued in The Era of Tyrannies: Essays on Socialism and War (1938): "Lassalle was the first man in Germany, the first in Europe, who succeeded in organising a party of socialist action. Yet he viewed the emerging bourgeois parties as more inimical to the working class than the aristocracy' and hence he supported universal manhood suffrage at a time when the liberals preferred a limited, property-based suffrage which excluded the working class and enhanced the middle classes. This created a strange alliance between Lassalle and Bismarck."

Otto von Bismarck later admitted that he had been in contact with Lassalle: "I saw him perhaps three or four times altogether... He attracted me as an individual. He was one of the most intelligent and likable men I had ever come across. He was very ambitious and by no means a republican. He was very much a nationalist and a monarchist. His ideal was the German Empire, and here was our point of contact. As I have said he was ambitious, on a large scale, and there is perhaps room for doubt as to whether, in his eyes, the German Empire ultimately entailed the Hohenzollern or the Lassalle dynasty.... Our talks lasted for hours and I was always sorry when they came to an end."

Ferdinand Lassalle became romantically involved with a young woman, Helene von Dönniges, and in the summer of 1864 they decided to marry. Her father objected to the relationship and she eventually agreed to marry a nobleman named Bajor von Racowitza. Lassalle sent a challenge to duel to Racowitza. A duel took place on the morning of 28th August 1864. Lassalle was mortally wounded, and he died on 31st August.

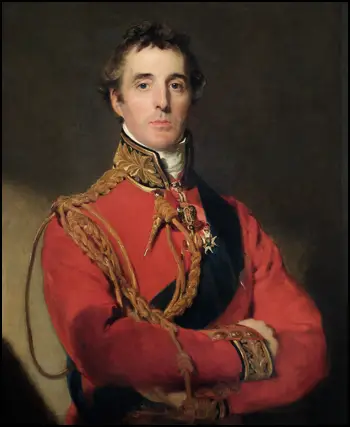

On this day in 1831 Duke of Wellington explains why he is against universal suffrage. "The conduct of government would be impossible, if the House of Commons should be brought to a greater degree under popular influence. That is the ground on which I stand in respect to the question in general of Reform in Parliament. I confess that I see in thirty members for rotten boroughs, thirty men, I don't care of what party, who would preserve the state of property as it is; who would maintain by their votes the Church of England, its possessions, its churches and universities. I don't think that we could spare thirty or forty of these representatives, or with advantage exchange them for thirty or forty members elected for the great towns by any new system."

On this day in 1848, a group of religious people who supported Chartism held a meeting in London. People who attended the meeting included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class.

Frederick Denison Maurice was acknowledged as the leader of the group and his book The Kingdom of Christ (1838) became the theological basis of Christian Socialism. In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. Christian Socialists promoted the cooperative ideas of Robert Owen and suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society.

Maurice's biographer, Bernard Reardon, has argued: "In 1850 Maurice publicly accepted the designation Christian socialist for his movement.... He disliked competition as fundamentally unchristian, and wished to see it, at the social level, replaced by co-operation, as expressive of Christian brotherhood... Maurice held Bible classes and addressed meetings attended by working men who, although his words carried less of social and political guidance than moral edification, were invariably impressed by the speaker. But the actual means by which the competitiveness of the prevailing economic system was to be mitigated was judged to be the creation of co-operative societies."

The Christian Socialists published two journals, Politics of the People (1848-1849) and The Christian Socialist (1850-51). The group also produced a series of pamphlets under the title Tracts on Christian Socialism. Other initiatives included a night school in Little Ormond Yard and helping to form eight Working Men's Associations. In 1850 Thomas Hughes, Edward Neale, Lloyd Jones, and other members of the group helped to establish the London Cooperative Store.

Disagreements between members resulted in the Christian Socialists being inactive between 1854 and the late 1870s. The 1880s saw a revival of the movement and by the end of the century a variety of Christian Socialist groups had been formed including the Socialist Quaker Society, the Roman Catholic Socialist Society, the Guild of St. Matthew, and the Christian Social Union.

Christian Socialists also dominated the leadership of the Independent Labour Party formed in 1893. This included James Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, Katharine Glasier, Margaret McMillan and Rachel McMillan.

The Christian Socialist movement also influenced many of the leaders of the American Socialist Party such as Norman Thomas and Upton Sinclair.

On the outbreak of the First World War a large number of Christian Socialists joined the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred."

Wilfred Wellock, a Christian Socialist, joined the Independent Labour Party. "As I moved about the country after 1920 it was next to impossible to secure a response to any kind of spiritual appeal... The only organisation that appeared to be advancing was the Independent Labour Party... The rapid march of the socialist movement in Britain at this time, with the Independent Labour party as its spearhead, owed its success to its essentially spiritual appeal. The ILP inherited the spiritual idealism of the early Christian Socialists and of the artist-poet-craftmanship school of William Morris... This was the only kind of socialism that appealed to me... I am a socialist, provided you give a spiritual interpretation to the term... I have only recently decided to enter practical politics since I have seen the possibility of making politics, through the introduction of spiritual considerations, a veritable means of social transformation."

In 1921 Wellock published Christian Communism. He argued that is " our business is to create a Christian Communist consciousness, and to let the revolution, or what there be, come out of that... We must concentrate upon the ideal, preach and teach it everywhere, proclaim it in the cities, in the churches, at the street corners - go into the highways and the hedges and compel the people to see life anew, and in the light of a finer ideal to re-create the world."

There was a revival of Christian Socialism after the outbreak of the Second World War. The writer, John Middleton Murry, argued for "socialist-communities, prepared for hardship and practised in brotherhood, might be the nucleus of a new Christian Society, much as the monasteries were during the dark ages."

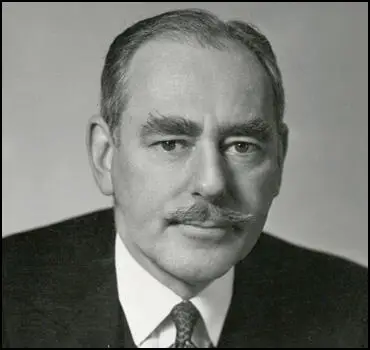

On this day in 1893 politician Dean Acheson was born in Middletown, Connecticut. After being educated at Yale University (1912-15) and Harvard Law School (1915-18) he became private secretary to the Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis (1919-21).

A supporter of the Democratic Party, Acheson worked for a law firm in Washington before Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him as Under Secretary of the Treasury in 1933. During the Second World War Acheson served as Assistant Secretary in the Department of State.

In 1945 Harry S. Truman selected Acheson as his Under Secretary of State. Over the next two years Acheson played an important role in devising both the Truman Doctrine and the European Recovery Program (ERP). Acheson believed that the best way to halt the spread of communism was by working with progressive forces in those countries threatened by revolution. After becoming Secretary of State in 1949, Acheson and George Marshall, Secretary of Defence, came under increasing attack from right-wing politicians who considered the two men to be soft on communism.

On 9th February, 1950, Joe McCarthy made a speech at Wheeling where he attacked Acheson as "a pompous diplomat in striped pants". He claiming that he had a list of 250 people in the State Department known to be members of the American Communist Party. McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

McCarthy had obtained his information from his friend, J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). William Sullivan, one of Hoover's agents, later admitted that: "We were the ones who made the McCarthy hearings possible. We fed McCarthy all the material he was using."

Dean Acheson also upset the right-wing when he took the side of Harry S. Truman in his dispute with General Douglas MacArthur over the Korean War. Acheson and Truman wanted to limit the war to Korea whereas MacArthur called for the extension of the war to China. Joe McCarthy once again led the attack on Acheson: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, 'Now let's be calm, let's do nothing'. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murderers."

In April 1951, Harry S. Truman removed GeneralDouglas MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea. McCarthy called for Truman to be impeached and suggested that the president was drunk when he made the decision to fire MacArthur: "Truman is surrounded by the Jessups, the Achesons, the old Hiss crowd. Most of the tragic things are done at 1.30 and 2 o'clock in the morning when they've had time to get the President cheerful."

Acheson was the main target of McCarthy's anger as he believed Harry S. Truman was "essentially just as loyal as the average American". However, Truman was president "in name only because the Acheson group has almost hypnotic powers over him. We must impeach Acheson, the heart of the octopus."

Harry S. Truman decided not to stand for president in 1952 and Acheson's close friend, Adlai Stevenson, was chosen as the Democratic Party candidate for the election. It was one of the dirtiest in history with Richard Nixon, the Republican vice-presidential candidate, leading the attack on Stevenson. Speaking in Indiana, Nixon described Stevenson as a man with a "Ph.D. from Dean Acheson's cowardly college of Communist containment."

The election campaign of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon was a great success and in November they easily defeated Adlai Stevenson by 33,936,252 votes to 27,314,922. Disillusioned by the smear campaign, Acheson returned to his private law practice. He also wrote several books on politics including Power and Diplomacy (1958), Morning and Noon (1965), Present at the Creation (1970) and The Korean War (1971).

Dean Acheson died at Sandy Spring, Maryland, on 12th October, 1971.

On this day in 1913 Christabel Pankhurst admits the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) were responsible for burning down the home of Arthur Du Cros the MP for Hastings. The previous year Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

On this day in 1914 Keir Hardie makes a speech on the Modern World.

"I shall not weary you by repeating the tale of how public opinion has changed during those twenty-one years. But, as an example, I may recall the fact that in those days, and for many years thereafter, it was tenaciously upheld by the public authorities, here and elsewhere, that it was an offence against laws of nature and ruinous to the State for public authorities to provide food for starving children, or independent aid for the aged poor. Even safety regulations in mines and factories were taboo. They interfered with the ‘freedom of the individual’. As for such proposals as an eight-hour day, a minimum wage, the right to work, and municipal houses, any serious mention of such classed a man as a fool.

These cruel, heartless dogmas, backed up by quotations from Jeremy Bentham, Malthus, and Herbert Spencer, and by a bogus interpretation of Darwin’s theory of evolution, were accepted as part of the unalterable laws of nature, sacred and inviolable, and were maintained by statesmen, town councillors, ministers of the Gospel, and, strangest of all, by the bulk of Trade Union leaders. That was the political, social and religious element in which our Party saw the light. There was much bitter fighting in those days. Even municipal contests evoked the wildest passions.And if today there is a kindlier social atmosphere it is mainly because of twenty-one years’ work of the ILP.

Scientists are constantly revealing the hidden powers of nature. By the aid of the X-rays we can now see through rocks and stones; the discovery of radium has revealed a great force which is already healing disease and will one day drive machinery; Marconi, with his wireless system of telegraphy and now of telephony, enables us to speak and send messages for thousands of miles through space.

Another discoverer, through means of the same invisible medium, can blow up ships, arsenals, and forts at a distance of eight miles. But though these powers and forces are only now being revealed, they have existed since before the foundation of the world. The scientists, by sympathetic study and laborious toil, have brought them within our ken. And so, in like manner, our Socialist propaganda is revealing hidden and hitherto undreamed of powers and forces in human nature.

Think of the thousands of men and women who, during the past twenty-one years, have toiled unceasingly for the good of the race. The results are already being seen on every hand, alike in legislation and administration. And who shall estimate or put a limit to the forces and powers which yet lie concealed in human nature?

Frozen and hemmed in by a cold, callous greed, the warming influence of Socialism is beginning to liberate them. We see it in the growing altruism of Trade Unionism. We see it, perhaps, most of all in the awakening of women. Who that has ever known woman as mother or wife has not felt the dormant powers which, under the emotions of life, or at the stern call of duty are even now momentarily revealed? And who is there who can even dimly forecast the powers that lie latent in the patient drudging woman, which a freer life would bring forth? Woman, even more than the working class, is the great unknown quantity of the race.

Already we see how their emergence into politics is affecting the prospects of men. Their agitation has produced a state of affairs in which even Radicals are afraid to give more votes to men, since they cannot do so without also enfranchising women. Henceforward we must march forward as comrades in the great struggle for human freedom.

The Independent Labour Party has pioneered progress in this country, is breaking down sex barriers and class barriers, is giving a lead to the great women’s movement as well as to the great working-class movement. We are here beginning the twenty-second year of our existence. The past twenty-one years have been years of continuous progress, but we are only at the beginning. The emancipation of the worker has still to be achieved and just as the ILP in the past has given a good, straight lead, so shall the ILP in the future, through good report and through ill, pursue the even tenor of its way, until the sunshine of Socialism and human freedom break forth upon our land.

On this day in 1942 Muriel Green writes about the use of gas-masks. Muriel was in Gloucester when there was a gas leak from a building: "Very few masks were visible except soldiers and an odd child." A study at the beginning of the war suggested that only about 75 per cent of people in London were obeying government instructions regarding gas masks. By the beginning of 1940 almost no one bothered to carry their gasmask with them. The government now announced that Air Raid Wardens would be carrying out monthly inspections of gas masks. If a person was found to have lost the gas mask they were forced to pay for its replacement.

Jessica Mitford wrote about the mood the government was creating: "All sorts of emergency measures were being taken by the Government to prepare the people for war. Thousands lined up patiently to be measured for gas-masks, only to find out that because of the haste with which the masks were manufactured the parts which were supposed to intercept gas had been inadvertendy left out. Trenches were dug in Hyde Park, causing mass discontent on the part of nannies, who complained that their little charges were always falling in. Apart from the bitter jokes caused by these inept arrangements, the atmosphere was on the whole one of dreary calm, of apathetic bowing to the inevitable." (76)

On this day in 1944 Anne Frank writes about the persecution of the Jews. "Who has inflicted this upon us? Who has made us Jews different to all other people? Who has allowed us to suffer so terribly up till now? It is God that has made us as we are, but it will be God too, who will raise us up again. If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left, when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will then be held up as an example. Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason and that reason only do we have to suffer now."

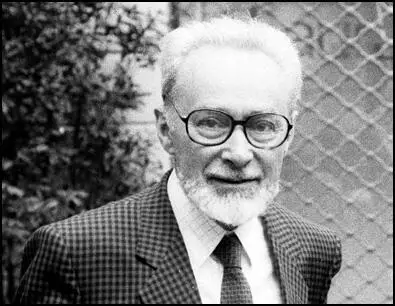

On this day in 1987 writer Primo Levi committed suicide. Primo Levi was born to Jewish parents in Turin, Italy, on 31st July, 1919. He studied chemistry at the University of Turin and graduated in 1941.

Levi moved to northern Italy to join the resistance against Benito Mussolini but was was captured in December, 1943 and sent to Auschwitz.

Levi was one of the few inmates that the Red Army found alive when they liberated the camp in 1945. After the war Levi wrote an account of his experiences in Survival in Auschwitz (1947). Other autobiographical books include The Truce (1963) and The Drowned and the Saved (1986).

Levi was the author of several acclaimed books including The Periodic Table (1975), The Monkey's Wrench (1978), If Not Now, When? (1982) and Other People's Trades (1985).

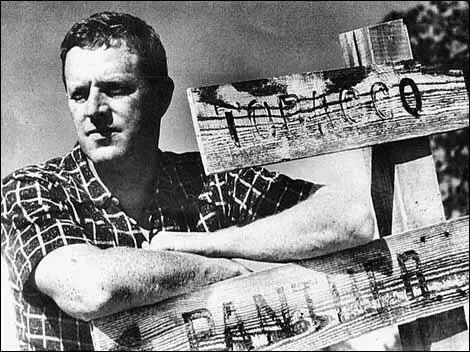

On this day in 1987 Erskine Caldwell died in Arizona. Caldwell, the son of a missionary, was born in Coweta, Georgia, on 17th December, 1903. As a child he travelled with his father and developed a concern for the poor. He was educated at the University of Virginia but did not graduate.

Caldwell moved to Maine in 1926 where he began writing for various journals including the New Masses and the Yale Review. He also published several novels but it was not until Tobacco Road (1932), a novel about the plight of poor sharecroppers, that critics began to take notice of his work. Dramatized by Jack Kirkland in 1933, it made American theatre history when it ran for over seven years on Broadway.

His next novel, God's Little Acre (1933) was also about poor whites living in the rural South. Both novels dealt with social injustice and many people objected to the impression it gave of America. When the New York Society for the Prevention of Vice tried to stop the book from being sold, Caldwell took the case to court and with the testimony of critics such as H. L. Mencken and Sherwood Anderson, won his case.

In 1936 Caldwell met and married the photographer, Margaret Bourke-White. They collaborated on You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), a documentary account of impoverished living conditions in the South. Other books by the couple included Russia at War (1942), North of the Danube (1975) and Say, is This the U.S.A.? (1977).

During the Second World War he worked as a newspaper reporter in the Soviet Union. An account of his experiences appeared in All Out on the Road to Smolensk (1942) and Call It Experience (1951). By the late 1940s Caldwell had sold more books than any author in America's history. God's Little Acre alone sold over fourteen million copies. His attacks on poverty, racism and the tenant farming system, had a significant impact on public opinion.

Caldwell wrote numerous short stories: collections include Jackpot (1940) and The Courting of Susie Brown (1952). Essays on his travels throughout the United States appeared in Around About America (1964) and Afternoons in Mid-America (1976).