On this day on 2nd September

On this day in 44 BC Cicero launches the first of his attacks on Mark Antony. Earlier, Mark Antony left Rome for for Gaul and Cicero assumed unofficial leadership of the senate. Over the next few months he made several attacks on Antony and urged the people to give their support to Caesar's great nephew and adopted son, Octavian. He thought that he had more chance of controlling a 19 year man than an experienced soldier and politician in his prime.

Antony arrived back in Rome and on 2nd September, 43 BC, he made a speech in the Senate where he attacked "Cicero's consulship and the whole career, blaming him for, among other things, the murder of Clodius, the Civil War, and Caesar's assassination. It was a comprehensive attack: he even found space in it to ridicule Cicero's poetry. Naturally enough, perhaps, Cicero immediately began work on a written rebuttal - the Second Philippic. This was essentially the speech that he would have given in reply to Anthony had he been able to: it is written exactly as if delivered in the senate on 19 September."

Cicero was especially angry that Mark Anthony had quoted from private letters that he had received from him in the past: "He also read letters which he said that I had sent to him, like a man devoid of humanity and ignorant of the common usages of life. For whoever, who was even but slightly acquainted with the habits of polite men, produced in an assembly and openly read letters which had been sent to him by a friend, just because some quarrel had arisen between them? Is not this destroying all companionship in life, destroying the means by which absent friends converse together? How many jests are frequently put in letters, which, if they were produced in public, would appear stupid! How many serious opinions, which, for all that, ought not to be published! Let this be a proof of your utter ignorance of courtesy."

Cicero defended the content of his letters: "For what expression is there in those letters which is not full of humanity and service and benevolence? And the whole of your charge amounts to this, that I do not express a bad opinion of you in those letters; that in them I wrote as to a citizen, and as to a virtuous man, not as to a wicked man and a robber. But your letters I will not produce, although I fairly might, now that I am thus challenged by you; letters in which you beg of me that you may be enabled by my consent to procure the recall of some one from exile; and you will not attempt it if I have any objection, and you prevail on me by your entreaties. For why should I put myself in the way of your audacity? When neither the authority of this body, nor the opinion of the Roman people, nor any laws are able to restrain you."

Cicero went on to deal with Mark Antony's criticisms of his consulship. "Marcus Antonius disapproves of my consulship; but it was approved of by Publius Servilius - to name that man first of the men of consular rank who had died most recently. It was approved of by Quintus Catulus, whose authority will always carry weight in this republic; it was approved of by the two Luculli, by Marcus Crassus, by Quintus Hortensius, by Caius Curio, by Caius Piso, by Marcus Glabrio, by Marcus Lepidus, by Lucius Volcatius, by Caius Figulus, by Decimus Silanus and Lucius Murena, who at that time were the consuls elect; the same consulship also which was approved of by those men of consular rank, was approved of by Marcus Cato; who escaped many evils by departing from this life, and especially the evil of seeing you consul. But, above all, my consulship was approved of by Cnæus Pompeius, who, when he first saw me, as he was leaving Syria, embracing me and congratulating me, said, that it was owing to my services that he was about to see his country again. But why should I mention individuals? It was approved of by the senate, in a very full house, so completely, that there was no one who did not thank me as if I had been his parent, who did not attribute to me the salvation of his life, of his fortunes, of his children, and of the republic."

Cicero has pointed out that Mark Antony's speech in the Senate was full of contradictions: "But you are so senseless that throughout the whole of your speech you were at variance with yourself; so that you said things which had not only no coherence with each other, but which were most inconsistent with and contradictory to one another; so that there was not so much opposition between you and me as there was between you and yourself. You confessed that your stepfather had been implicated in that enormous wickedness, yet you complained that he had had punishment inflicted on him. And by doing so you praised what was peculiarly my achievement, and blamed that which was wholly the act of the senate. For the detection and arrest of the guilty parties was my work, their punishment was the work of the senate. But that eloquent man does not perceive that the man against whom he is speaking is being praised by him, and that those before whom he is speaking are being attacked by him."

Cicero would have liked to have made the speech in the Senate but "armed men are actually between our benches". What is more these armed men were foreign soldiers: "Let us inquire then whether it was better for the arms of wicked men to yield to the freedom of the Roman people, or that our liberty should yield to your arms. Nor will I make any further reply to you about the verses. I will only say briefly that you do not understand them, nor any other literature whatever. That I have never at any time been wanting to the claims that either the republic or my friends had upon me; but nevertheless that in all the different sorts of composition on which I have employed myself, during my leisure hours, I have always endeavoured to make my labours and my writings such as to be some advantage to our youth, and some credit to the Roman name. But, however, all this has nothing to do with the present occasion."

Mark Antony responded by forming an alliance with Octavian and Marcus Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. The Triumvirate began proscribing their enemies and potential rivals. Cicero and all of his contacts and supporters were numbered among the enemies of the state, even though Octavian argued for two days against Cicero being added to the list. Cicero was caught on 7th December 43 BC, on his way to take a ship destined for Macedonia. Cicero's last words are said to have been, "There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly." After he was killed his head was cut off. On Antony's instructions his hands, which had penned the articles he had written against him, were cut off as well; these were nailed along with his head on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum. According to Cassius Dio Antony's wife Fulvia took Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed it repeatedly with her hairpin in final revenge against Cicero's power of speech.

The writings of Cicero had a large influence on Renaissance humanism. According to Anthony Grayling, the author of Ideas that Matter (2009): "The Renaissance valued Cicero not merely for his style but for his humanism in the modern sense, expressed as belief in the value of the human individual. He argued that individuals should be autonomous, free to think for themselves and possessed of rights that define their responsibilities; and that all men are brothers... The endowment of reason confers on people a duty to develop themselves fully, he said, and to treat one another with generosity and respect. This outlook remains the ideal of contemporary humanism today."

On this day in 1666 the Great Fire of London breaks out in a baker's shop in London. As the result of a strong east wind, the fire raged for four four days destroying 87 churches and more than 13,000 houses. The fire was eventually stopped by blowing up buildings in its path.

Charles II had to appoint someone to take charge of rebuilding London. After much thought the king gave the job to his childhood friend, Christopher Wren. This included the task of building fifty-two new churches.

Wren was also commissioned to design and rebuild St. Paul's Cathedral. St. Paul's took thirty-five years to build. The most dramatic aspect of St. Paul's was its great dome. It was the second largest dome ever built (the largest was St. Peter's Basilica in Rome). Both domes were based on the one in the Pantheon built by the ancient Romans.

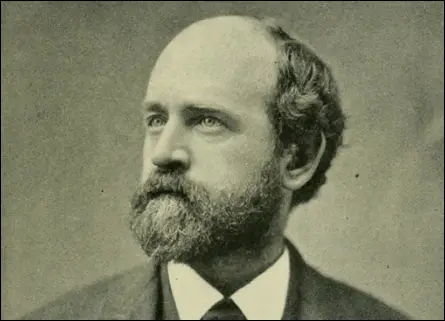

On this day in 1839 economist Henry George, the second of ten children, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 21st September 1839. He left school at 14 and went to sea as a foremast boy in April 1855. On his return he settled in California where he became a typesetter and printer.

By the 1860s he wrote for several newspapers and eventually became the owner of the San Francisco Evening Post. George was a crusading reporter who was later to have a considerable influence on a generation of investigative journalists such as Benjamin Flower, Frank Norris, Ida Tarbell, Charles Edward Russell, Lincoln Steffens, David Graham Phillips, C. P. Connolly, Upton Sinclair and Ray Stannard Baker.

In 1870 George published Our Land and Land Policy. In the book he developed the philosophy and economic ideology known as Georgism. He argued that everyone owns what he or she creates, but that everything found in nature, most importantly land, belongs equally to all humanity.

Henry George followed this with Progress and Poverty (1877). In the book he tried to explain the growing gap between rich and poor. "The reason why, in spite of the increase of productive power wages constantly tend to a minimum which will give but a bare living, is that, with increase in productive power, rent tends to even greater increase, thus producing a constant tendency to the forcing down of wages."

George went on to argue: "It is true that wealth has been greatly increased, and that the average of comfort, leisure and refinement has been raised; but these gains are not general. In them the lowest class do not share. This association of poverty with progress is the great enigma of our times. There is a vague but general feeling of disappointment; an increased bitterness among the working classes; a widespread feeling of unrest and brooding revolution. The civilized world is trembling on the verge of a great movement. Either it must be a leap upward, which will open the way to advances yet undreamed of, or it must be a plunge downward which will carry us back toward barbarism."

In these two books Henry George argued that the gap between the rich and the poor could only be closed by replacing the various taxes levied on labour and capital with a single tax on the value of property. Paul Thompson argues in his book, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967) that the book resulted in the growth in socialism: "The real socialist revival was set off by Henry George, the American land reformer, whose English campaign tour of 1882 seemed to kindle the smouldering unease with narrow radicalism. This radical voice from the Far West of America, a land of boundless promise, where, if anywhere, it might seem that freedom and material progress were secure possessions of honest labour, announced grinding poverty, the squalor of congested city life, unemployment, and utter helplessness."

James Keir Hardie also read Progress and Poverty. His friend Philip Snowden later argued: "Keir Hardie told me that it was Progress and Poverty which gave him his first ideas of socialism... No book ever written on the social problem made so many converts. Economic facts and theories have never been presented in such an attractive way. Although Henry George was not a socialist, his book led many of his readers to socialism."

Tom Mann was a trade union leader who read Progress and Poverty: "In 1886 I read Henry George's book, Progress and Poverty. This was a big event for me; it impressed me as by far the most valuable book I had so far read. It enabled me to see more clearly the vastness of the social problem, to realize that every country was confronted by it... His book was a fine stimulus to me, full of incentive to noble endeavour, imparting much valuable information, throwing light on many questions of real importance, and giving me what I wanted - a glorious hope for the future of humanity, a firm conviction that the social problem could and would be solved. I must again give a reminder that Socialism was known only to a few persons, and that no Socialist organization existed at that time."

Henry Snell agreed: "I was one of the many thousands of young men whose political and social views were greatly stimulated by Henry George's famous book Progress and Poverty, which, if measured by the breadth and the depth of its influence on the thoughtful workmen of the eighties, must be considered as one of the greatest political documents of that generation."

Progress and Poverty sold over two million copies. George made six lecture tours of Europe where there was more interest in his views than in the USA. Philip Snowden was one of those who saw him in England: "Henry George had a very impressive platform style. In appearance he was of middle height, well built, had a full, brown beard, and would have passed for a Nonconformist minister. His style of speaking was conversational, rather than oratorical."

As well as writing for magazines such as Arena in the United States, George published several more books including Social Problems (1883), Protection or Free Trade (1886), Perplexed Philosopher (1892) and Science of Political Economy (1897).

Henry George died on 29th October, 1897. An estimated 100,000 people attended the funeral.

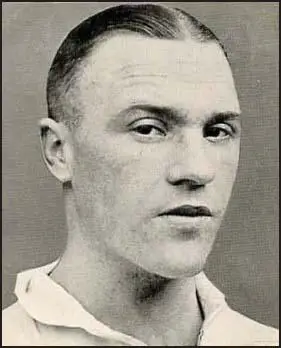

On this day in 1913 Bill Shankly, the son of John and Barbara Shankly, was born at the mining village of Glenbuck in Scotland. Bill had four brothers (John, Bob, Jimmy and Alec) and five sisters (Netta, Elizabeth, Isobel, Barbara and Jean).

Although most of the men living in the village worked as miners, John Shankly was a tailor. People living in Glenbuck were strong trade unionists and during his youth Bill Shankly developed socialist beliefs. "The socialism I believe in is not really politics. It is a way of living. It is humanity. I believe the only way to live and to be truly successful is by collective effort, with everyone working for each other, everyone helping each other, and everyone having a share of the rewards at the end of the day."

Bill Shankly's mother was very interested in football. Her two brothers, Robert Blyth and and William Blyth, both moved to England to play professional football. Both became involved in the administration of football with Robert being appointed chairman of Portsmouth and William was director of Carlisle United for many years.

Bill Shankly attended the local village school: "We played football in the playground, of course, and sometimes we got a game with another school, but we never had an organized school team. It was too small a school. If we played another school we managed to get some kind of strip together, but we played in our shoes."

Bill Shankly left school at 14 and like the other boys in the village went to work at the Glenbuck Colliery. As he later recalled: "My wages would be no more than two shillings and sixpence a day. My job was to empty the trucks when they came up full of coal and send them back down the pit again and to sort out the stones from the coal on a conveyer-belt... After about six months working at the pit top, a job that was active but not heavy, I went down to the pit bottom. The coal mines and pits were the first places to have electricity, before people had it in their houses, and the pit was like Piccadilly Circus. First I would shift full trucks and put them into the cages and then take out the empty trucks and run them along to where they were loaded."

Shankly played junior football for for Cronberry Eglinton. In 1932 a scout working for Carlisle United, saw Shankly play and arranged for him to join the club. Like his four brothers, John Shankly, Bob Shankly, Jimmy Shankly and Alec Shankly, Bill was now a professional footballer. As he later pointed out in his autobiography, Shankly: "All the boys became professional footballers and once, when we were all at our peaks, we could have beaten any five brothers in the world." In fact, despite only having a population of less than a 1,000 people, the village produced near fifty professional footballers in a sixty year period.

Bill Shankly was transferred to Preston North End for £500 in 1933. A teetotaler, non-smoker and fitness fanatic, this very energetic 20 year old, formed a great partnership with former English international, Robert Kelly. In the 1933-34 season Kelly and Shankly helped the club win promotion to the First Division.

Kelly, now aged 41, was considered too old for First Division football and was allowed to become player manager at Carlisle United. Preston signed another veteran, Ted Critchley, to replace Kelly. Other players brought in that year included Jimmy Maxwell (Kilmarnock) and Jimmy Dougal (Falkirk). In the 1934-35 season Preston finished 11th in the league. Maxwell, who played at centre-forward, was the club's leading scorer with 26 league and cup goals.

The following season Preston North End persuaded the Scottish international, Tom Smith, to join the club. Other signings that year included the brothers, Hugh O'Donnell and Francis O'Donnell, from Celtic.

In the 1935-36 season, Preston finished 7th in the league. Jimmy Maxwell was again top scorer with 19 goals in all competitions. Shankly, a powerful wing half, had emerged as the most important player in the team. He rarely missed a game and helped Preston North End reach the 1937 FA Cup Final against Sunderland at Wembley. Francis O'Donnell scored in the first-half but with Raich Carter in top form, Sunderland responded by scoring three in reply.

At the beginning of the next season, Preston made two important signings. In September, 1937, Preston purchased the high scoring George Mutch, from Manchester United for £5,000. The following month, Robert Beattie a skillful inside forward, arrived from Kilmarnock for a fee of £2,500. They joined fellow Scotsmen, Bill Shankly, Jimmy Dougal, Andrew Beattie, Jimmy Maxwell, Tom Smith, Hugh O'Donnell, Francis O'Donnell and Andrew McLaren.

In the 1937-38 season Preston North End (49 points) finished 3rd in the First Division of the Football League behind Arsenal (52) and Wolverhampton Wanderers (51). Preston also had another successful run in the 1937-38 FA Cup. Preston beat West Ham United in the 3rd round with George Mutch scored a hat trick. Mutch also scored goals in the 4th round against Leicester City and in the semi-final when Preston beat Aston Villa 2-1.

In the FA Cup Final Preston played Huddersfield Town. This was the first time that a whole match was shown live on television. Even so, far more people watched the game in the stadium as only around 10,000 people at the time owned television sets. No goals were scored during the first 90 minutes and so extra-time was played. In the last minute of extra-time, Bill Shankly put George Mutch through on goal. Alf Young, Huddersfield's centre-half, brought him down from behind and the referee had no hesitation in pointing to the penalty spot. Mutch was injured in the tackle but after receiving treatment he got up and scored via the crossbar. It was the only goal in the game and Shankly won a cup winners' medal.

Shankly had a magnificent season and on 9th April, 1938 he won his first international cap when he played for Scotland against England at Wembley. Also in the Scottish team were Preston colleagues, George Mutch, Andrew Beattie, Tom Smith and Francis O'Donnell. Scotland won 1-0 with Mutch scoring the only goal of the game. Later that season, two other Preston players, Jimmy Dougal and Robert Beattie, were called up to play for Scotland.

Shankly also played for Scotland against Northern Ireland (October, 1938), Wales (November, 1938), Hungary (December, 1938) and England (April, 1939). Shankly's international career was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War. Games in the Football League were brought to an end as the government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit. However, the clubs were divided into seven regional areas where games could take place. In the 1940-1941 season Preston North End needed to win their last game against Liverpool to win the North Regional League title. The nineteen year old Andrew McLaren scored all six goals in the 6-1 victory.

Preston North End also took part in the 1941 Football League War Cup. The teenage Andrew McLaren scored five of the goals in Preston's 12-1 victory over Tranmere. He also scored a hat-trick in the fourth-round tie against Manchester City. Preston reached the final by beating Newcastle United 2-0. The Preston team that faced Arsenal at Wembley on 31st May was: Jack Fairbrother, Frank Gallimore, William Scott, Bill Shankly, Tom Smith, Andrew Beattie, Tom Finney, Andrew McLaren, Jimmy Dougal, Robert Beattie and Hugh O'Donnell.

The game took place in front of a 60,000 crowd. Arsenal was awarded a penalty after only three minutes but Leslie Compton hit the foot of the post with the spot kick. Soon afterwards Andrew McLaren scored from a pass from Tom Finney. Preston dominated the rest of the match but Dennis Compton managed to get the equaliser just before the end of full-time.

The replay took place at Ewood Park, the ground of Blackburn Rovers. The first goal was as a result of a move that included Tom Finney and Jimmy Dougal before Robert Beattie put the ball in the net. Frank Gallimore put through his own goal but from the next attack, Beattie scored again. It was the final goal of the game and Preston ended up the winners of the cup.

Bill Shankly retired from playing football in 1948. During his time at Preston North End he scored 14 goals in 337 league and cup games. This included a record 43 successive FA Cup ties.

Shankly became the coach of Preston's reserve team but in March, 1949 he agreed to become manager of Carlisle United. The club finished 3rd in the Third Division (North) league in 1950-51. Carlisle had little money to spend and in 1951 he resigned complaining about a lack of resources. It was a similar story at Grimsby Town (1951-54) and Workington (1954-55).

In 1956 Shankly became assistant manager under Andrew Beattie at Huddersfield Town, a club that had just been relegated from the First Division of the Football League. Soon after joining the club, Shankly signed the 15 year old Dennis Law. Over the next three years Shankly was involved in keeping Law at the club. This included an offer of £45,000 from Everton.

Bill Shankly did not manage to get Huddersfield Town back into the First Division finishing 12th (1956-57), 9th (1957-58) and 14th (1958-59). In December 1959, Shankly became manager of Liverpool, another Second Division club trying to get promotion to the top league. Shankly got them into 3rd place in 1959-60. He repeated this in 1960-61, but the following year won the championship with 62 points.

Wilf Mannion was a great advocate of Shankly's man-management: "What I like about Bill is that he never panics. Even when things weren't going so well, he stuck to the same team and gave them a chance to settle down. 'Panic and all is lost,' is one of the Shankly maxims. Everything Bill does is done to plan. Even training is scheduled to a strict timetable. But that doesn't make him a strict disciplinarian. Far from it. He is one of the easiest-going characters I have met. Ask the players. He's always 'Bill' to them. There's no 'Mr' or 'Boss' when he's around. 'Let the players regard you as an equal,' says Bill, 'and you gain just as much respect.' I couldn't agree more."

Liverpool finished in a respectable 8th place in their first season back in the First Division. The following season (1963-64) they won the league with their arch-rivals, Everton, finishing in 3rd place. Over the next ten years Liverpool won the league on two more occasions: 1965-66 and 1972-73. They also won the FA Cup in 1974.

Shankly remained interested in politics and once said: "The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That's how I see football, that's how I see life."

In July, 1974, Shankly, now 60 years old, decided to retire. He later commented: "It was the most difficult thing in the world, when I went to tell the chairman. It was like walking to the electric chair." He was replaced by Bob Paisley. Soon after he retired Shankly was awarded the OBE.

Bill Shankly died of a heart attack on 28th September, 1981.

On this day in 1916 Lieutenant W. L. Robinson reports how he shot down a Zeppelin airship over England.

I climbed to 10,000 feet in 53 minutes. I saw nothing till 0110 hours when two searchlights picked up a Zeppelin south-east of Woolwich. By the time I had managed to climb to 12,000 feet. I made in the direction of the Zeppelin which was being fired on by a few anti-aircraft guns. I very slowly gained on it. It went behind some clouds, avoiding the searchlights, and I lost sight of it. After 15 minutes fruitless search I returned to my patrol.

At 0105 hours a Zeppelin was picked up by the searchlights over north-east London. Remembering my last failure I sacrificed height for speed and made nose down in the direction of the Zeppelin. I flew about 800 feet below it and distributed one drum from my Lewis gun along it. It seemed to have no effect. I then got behind it. By this time I was very close - 50 feet or less. I concentrated one drum on the underneath rear. I hardly finished the drum before I saw the part on fire. In a few seconds the whole rear part was blazing. I quickly got out of the way of the falling blazing Zeppelin and, being very excited, fired off a few red lights and dropped a parachute flare.

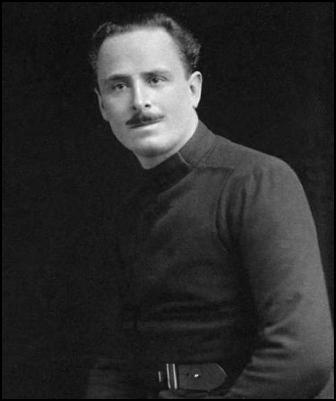

On this day in 1939 Oswald Mosley makes speech on the outbreak of the Second World War.

"We have said a hundred times that if the life of Britain were threatened we would fight again, but I am not offering to fight in the quarrel of Jewish finance in a war from which Britain could withdraw at any moment she likes, with her Empire intact and her people safe. I am now concerned with only two simple facts. This war is no quarrel of the British people, this war is a quarrel of Jewish finance, so to our people I give myself for the winning of peace."

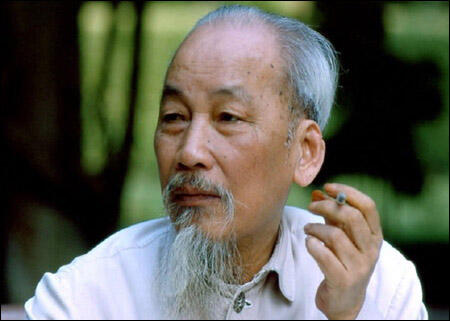

On this day in 1945 Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. When the Japanese surrendered to the Allies after the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945, the Vietminh was in a good position to take over the control of the country.

Unknown to the Vietminh Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin had already decided what would happen to post-war Vietnam at a summit-meeting at Potsdam. It had been agreed that the country would be divided into two, the northern half under the control of the Chinese and the southern half under the British.

After the Second World War France attempted to re-establish control over Vietnam. In January 1946, Britain agreed to remove her troops and later that year, China left Vietnam in exchange for a promise from France that she would give up her rights to territory in China.

France refused to recognise the Democratic Republic of Vietnam that had been declared by Ho Chi Minh and fighting soon broke out between the Vietminh and the French troops. At first, the Vietminh under General Vo Nguyen Giap, had great difficulty in coping with the better trained and equipped French forces. The situation improved in 1949 after Mao Zedong and his communist army defeated Chaing Kai-Shek in China. The Vietminh now had a safe-base where they could take their wounded and train new soldiers. xx