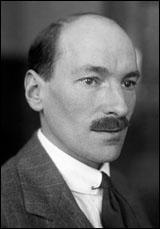

Clement Attlee: 1883-1918

Clement Attlee, the son of Henry Attlee, was born in Putney on 3rd January, 1883. His mother, Ellen Attlee, was the daughter of Thomas Simons Watson, who was educated at Cambridge University and became secretary of the Art Union. Clement was the seventh of eighth children and had three sisters and four brothers. (1)

For more than 200 years the Attlee family had become wealthy, primarily through corn mills and brewing. His grandfather, Richard Attlee had been especially successful. Henry, the ninth of his tenth children, was articled to the solicitors Druces, where he rose to become senior partner in 1897. He became one of His Majesty's Lieutenants of the City of London and eventually, in 1906, President of the Law Society. (2)

The family home was a large villa with two storeys. As well as a large garden they had their own tennis court. As well as three domestic servants, the family employed a full-time gardener. "On first appearance, Henry Attlee appeared rather austere, with a long white beard, top hat, and dress suit. All his children, however, remembered him as warm, convivial and affectionate. On those occasions when he had won a case in court, he was known to chase them through the garden and leap through the flowerbeds." In 1898 Henry Attlee purchased a large country house in Thorpe-le-Soken, which had 200 acres of land. (3)

Henry and Ellen Attlee were committed Anglicans and there was a strong tradition of "good works" in the family. "Every morning Henry Attlee said prayers before breakfast to the whole family and servants; after breakfast, psalms were read with Ellen Attlee presiding… Attlee was instilled with an enduring sense of Christian values." (4) Henry was on the council of St Bartholomew's Hospital in London and Ellen was involved in charitable activity through the church. The eldest son, Bernard, became a clergyman. The eldest daughter, Mary, went to South Africa as a missionary. (5)

Education of Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee was very close to his older brother Tom Attlee. At the age of nine he followed Tom to board at Northaw Place preparatory school in Hertfordshire. Other pupils at the time included William Jowitt and Hilton Young, two future MPs. Clement enjoyed his time at Northaw Place but considered its teaching methods eccentric and blamed the school for not giving him a good enough grounding in Latin and Greek. (6)

In 1896 at the age of thirteen went on, like all the boys in the Attlee family, to Haileybury College. He spent four years in the middle of his class and was never identified as a candidate for a scholarship to one of Britain's prestigious universities. According to John Bew: "Haileybury had hardened what was essentially Conservative - and most decidedly imperialist - political convictions. He was aware that such a thing as socialism existed but did not think it worth much consideration. As for the plight of the poor in England, he showed no sign of empathy; quite the contrary. One of his earliest poems, which appeared in the Haileybury magazine in 1899, was a strongly worded attack on the London cabbies who were striking at the time. Before long, he predicted, these upstarts would be forced to beg for their fares." (7)

Attlee came under the influence of his housemaster Frederick Webb Headley, who had right-wing political opinions, and was the author of Darwinism and Modern Socialism (1909). The principle theme of the book is a defence of capitalism, specifically of the ingenuity of capitalists large and small, concluding that socialism would never take root in Britain. If introduced socialism would have a "crushing, deadening influence" and would "introduce unjust and impossible economics". It would, Headley maintained, "destroy the main motives for enterprise and put an end to the struggle for existence, the action of which maintains the health and vigour of human communities." (8)

Attlee's views on politics can be discovered by his contribution to Haileybury School Debating Society. For example, he opposed the motion "that museums and picture galleries should be open on Sundays". What class, Attlee asked, would benefit from the opening of museums and galleries? Certainly not the poorer class, as they could not appreciate them. He thought that it would be giving the upper class another excuse for not going to church. It was introducing the thin end of the wedge." (9)

Clement's conservative views brought him into conflict with his father who was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party. He had many friends in the party including John Morley, who had served as Chief Secretary for Ireland and Secretary of State for India, who lived close by in Putney. Morley had also published biographies of Oliver Cromwell and William Ewart Gladstone. Both these books were later read by Clement Attlee. (10)

Henry Attlee and his sons disagreed about the Boer War. Whereas the boys felt the strong emotions of patriotism during the conflict, their father believed the good name of the country was being besmirched by the actions of a "rather unsavoury cosmopolitan clique of financiers in Johannesburg" who were falsely claiming to act in the interests of the empire. How could the British criticize the actions of other colonial powers in the "scramble for Africa" - such as Belgium, Germany and France - when it acted in ways that were just as ignoble? (11)

Francis Beckett claims that "Attlee was a perfectly able though undistinguished pupil, becoming a prefect but not head of house... He was so shy that he could hardly bring himself to speak in the school's Literary and Debating Society. He was given the job of running the house library because he had read all the books... For a small, shy bookworm without any talent for games, he contrived to stay out of trouble most of the time. If anyone knew what to look for, they might have seen a natural politician in the making." (12)

Clement Attlee entered University College to read Modern History in October 1901. His brother Tom was also at Oxford University and in his final year of Corpus Christi. The brothers relished the freedom of university, which contrasted to their regimented existence at Haileybury. They were given a generous stipend by their father and embraced the university lifestyle - rowing, reading and socializing. Tom later recalled: "Your time at Oxford was your own and you did not waste a bit of it." (13)

Attlee was not an outstanding student. Some tutors suggested he could have achieved a first-class degree, but found himself reading around the history syllabus. One of his tutors described him as a "level-headed, industrious, dependable man with no brilliance of style... but with excellent sound judgement." He received a second-class degree but developed a life-long interest in history. His sister Mary commented that his knowledge of history was "of the greatest help to him, for not only has it provided him with a sound understanding of the causes of tendencies in modern society, but it is a subject which gives every intelligent student of it perspective and a sense of balance." (14)

Attlee did not take an interest in politics or economics while at university. It did not cross his mind to question the order or structure of society. He admitted that at this time he was a "good old fashioned imperialist conservative". (15) He later recalled: "The capitalist system was as unquestioned as the social system. It was just there. It was not known under that name because one does not give a name to something of which one is unconscious." He later recalled: "In my day we were extraordinarily backward. I was a very backward boy myself - we knew nothing about socialism." (16)

Attlee wrote in his autobiography, As It Happened (1954): "Oxford University was at that time predominately Conservative though there was a strong Liberal group, notably at Ballioli, which counted among its undergraduates such men as R. H. Tawney and William Temple, the future Archbishop, whose influence on socialist thought was in later years to be so great. Socialism was hardly spoken of, although Sidney Ball at St. John's and A.J. Carlyle, at University College, kept the light burning. I was at this time a Conservative, but I did not take any active part in politics. I never belonged to any political club." (17)

In the autumn of 1904 he entered the Lincoln's Inn chambers of Sir Philip Gregory, a leading conveyancing lawyer, and was called to the bar by the Inner Temple in March 1906. This was achieved through his father's connections. He also studied under Theobald Matthew, a famous Common Law barrister. Attlee had a spell in his father's firm of solicitors, which he found boring. "Attlee devoted no great energy to the law, and was idling his life away in congenial London company, insulated from most practical cares by living at home." (18) He eventually came to the conclusion that he was "not really much interested in the law and had no ambition to succeed." (19)

Social Work

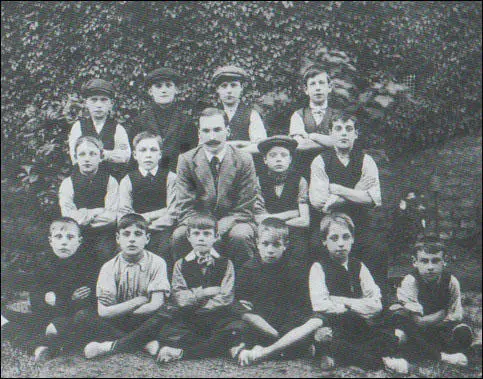

In October 1905, Clement and his younger brother, Laurence, was asked to inspect the work of Haileybury House. The founder of the settlement, Cecil Nussey, an old Haileyburian, while at Oxford University, became a disciple of the generation of social thinkers that had been inspired by the ideas of Thomas Hill Green, Professor of Moral Philosophy at Balliol College. "Green's ethical socialism was based on the premise that human self-perfection could only be achieved through society, and that society therefore had the moral obligation to ensure the best conditions for everyone. This entailed for the individual not random and remote acts of charity, but the obligation on the more fortunate to share their fuller lives with the poor." (20)

Nussey's idea was that old Haileyburians would become residents rather than as occasional visitors to the people living in the East End of London. The two brothers were given a tour of the Haileybury Club, an institution where working-class boys between the ages of fourteen and eighteen met under the supervision of Haileyburians. The school was in Stepney and was a different world from that in which they had been raised. "This was the dark heart of the East End - densely populated by dockworkers, casual labourers and notorious for unemployment, poverty, crime and disease." (21)

At first Attlee feared the idea of living with people from such a different background. Clement was so shy that he found it agonizing to talk to the boys. At first he agreed to give one night a week to the club. The club was open for five nights a week, from 8 to 10 pm. All the boys joined the Territorial Army and represented 'D' Company of the 1st Cadet Battalion of the Queen's Regiment. They took part in drilling and they learnt to clean and load rifles. The boys wore a uniform on club nights, "which gave them a pride in their appearance which their everyday rags could not offer." (22)

On 13th March 1906, Clement Attlee took a commission in the Territorial Army and became a second lieutenant. He was now spending several nights a week at the club. He later pointed out how this experience changed his political views. "A boy from a public school knowing little or nothing of social or industrial matters, who decides, perhaps at the invitation of a friend or from loyalty to his old school that runs a mission, or to the instinct of service that exists in everyone, to assist in running a boys' club.... The thoughtless schoolboy will have become interested in social problems in the concrete, and from this it is but a step to studying them in the abstract, and he soon sees how little his efforts can accomplish, and will perceive that the faults he sees are only the effects of greater causes." (23)

Attlee came to the conclusion it was "vital to break up the huge collection of people of one class living as it were among the natives and create a more natural system". He believed that social workers should live with the people who they were serving. In the autumn of 1907, the manager of Haileybury House resigned and Nussey asked Attlee if he would be interested in taking the job, a residential position with an annual salary of £50. He accepted and he moved into Haileybury House. He now had much more contact with the boys, often visiting their homes and talking with their parents. (24) Attlee later recalled that there was "no better way of getting to know what social conditions are like than in a boy's club. One learns much more of how people in poor circumstances live through ordinary conversation with them from studying volumes of statistics." (25)

Gradually, Attlee came to the conclusion that the capitalist system had to be reformed to ensure that all classes of society could have an accepted standard of living. The only way it was possible to understand how "people in poor circumstances" live was living among them and having the experiences yourself. Christian ethics had been a central part of Attlee's childhood, so serving others was nothing new. (26) It was by having conversations with the boys and their parents "was a step to examining the whole basis of our social and economic system." He now understood "why the Poor Law was so hated." (27) Roy Jenkins, described Attlee's experience in the East End as his "road to Damascus". (28)

Independent Labour Party

Clement came under the influence of his older brother, Tom Attlee. While at university he became very interested in the work of John Ruskin, the great Victorian art critic, writer and educationalist. He also began reading the novels of William Morris, including The Dream of John Ball (1888), a story about the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 and News from Nowhere (1889), his depiction of a socialist utopia. Tom joined the Christian Social Union, an organization established by Henry Scott Holland. He also volunteered in a boys' home in Hoxton. It had been founded by Frederick Denison Maurice, a professor of theology and one of the leading figures in the Christian Socialist movement. It taught pacifism whereas Clement's school taught military skills. (29)

Tom became a committed socialist and encouraged Clement to join the Fabian Society. At the first meeting he met one of its leaders, Edward Pease, and later claimed that the viewed him and Tom as if they were "two beetles who had crept under the door." During the next few weeks he also came into contact with H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb. Clement Attlee thought there was something remote and superior about these intellectuals and it was not long before he stopped attending meetings. (30)

On the suggestion of Tom Williams, a dockworker, Clement and Tom attended a meeting of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), founded by Keir Hardie in 1893. Both men became activists in the ILP - Clement in Stepney and Tom in Wandsworth. He read Hardie's book From Serfdom to Socialism (1907) and found his practical approach to achieving social reform, more appealing than utopianism or intellectualism. Within a few months this "young Tory had become a fervent socialist and a street-corner propagandist in the Independent Labour Party". (31) Clement later commented: "After looking into many social reform ideas (my elder brother and I) came to the conclusion that the economic and ethical basis of society was wrong." (31a)

Stepney ILP only had twelve members. As a result of its small size and the fact that he was one of the few with any time to spare, Attlee quickly became the branch secretary. (32) One reason that they had problems persuading men to join was the fear of losing their jobs if they admitted membership. During this period, Attlee spent four evenings a week at the club, one night at a ILP branch meeting and refereeing football matches on Saturday. He also addressed open-air meetings on a Sunday. (33) He found it difficult making speeches in public but as he later explained, it "at least cured my shyness." (34)

Attlee also became a member of the Labour Party. He got to know all its leaders and became close to Will Crooks and George Lansbury. In later years, Attlee often paid tribute to the humane and deeply moral creed of the early leaders. "What he admired about Crooks and Lansbury most, however, was their tolerance. Both were teetotalers, for example, but they appreciated the right of the working man to have a drink. They did not impose their own version of the good life on others. Crooks argued for a reduction in the number of pubs but did not want to ban them all." (35)

On 19th November, 1908, Henry Attlee died of a heart-attack. Henry left the two houses and £70,000 to his wife and children. His inheritance allowed Clement Attlee to commit his activities full-time to the socialist cause in Stepney. "I remember, on giving up practice at the bar, being congratulated by my friends in a poor district in much the same terms as would have been employed had I at last given up the drink." (36)

In 1909 he became secretary at Toynbee Hall, the best-known of the East End university settlements, but after a year he left because the atmosphere there did not chime in with his socialism. He later said the trustees of Toynbee regarded him as a "bit of a bolshie". Attlee did some lecturing at Ruskin College, and then in 1912 was appointed a lecturer in the social service department at the London School of Economics (LSE), after defeating Hugh Dalton largely because of his practical experience in the East End. "I was not appointed on the score of academic qualification, but because I was considered to have a good practical knowledge of social conditions." (37)

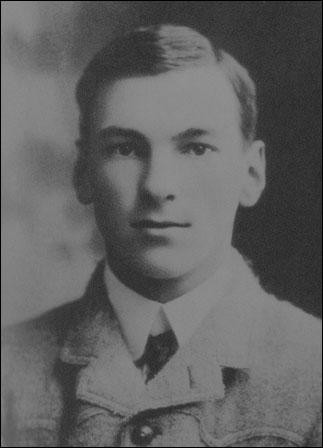

First World War

The Labour Party was completely divided by the First World War. Most of its leaders opposed the war, including Ramsay MacDonald, Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, John Glasier, George Lansbury, Alfred Salter, William Mellor and Fred Jowett. Others in the party such as Clement Attlee, Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, J. R. Clynes, William Adamson, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort. (38)

John Bew has argued that the main reason why Attlee supported the war effort concerned the fact that he had spent almost ten years as a second lieutenant in the 1st Cadet Battalion of the Queen's London Regiment. Many of the young boys he had trained were going to go to war. How would it look if the man who drilled them decided that his conscience could not allow him to join them on the front line? (39) The situation was very different at Tom's Christian Socialist boys club in Hoxton, as they did not have any military training: "The outbreak of the war brought great heart-searchings in the ranks of the Labour and Socialist Movement, especially in the membership of the Independent Labour Party. My brother Tom was a convinced conscientious objector and went to prison. I thought it my duty to fight." (40) Tom Attlee argued that as a Christian and a socialist, he must be a conscientious objector, making it clear from the start by joining the No-Conscription Fellowship. (41)

Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, the author of Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) has suggested that "his deep sense of duty drove him to join the army and to risk his life in service of his country." He was turned down initially on grounds of age (he was 31 and the maximum age was 30). Not to be deterred, he joined the Inns of Court Regiment Officer Training Corps as an instructor, as a potential route to a commission in the regular army. He also asked a former pupil of his at the LSE to ask her brother-in-law (who had command of one of the new Kitchener battalions). The resulted him in being commissioned as a lieutenant of the 6th South Lancashire Regiment and was put in command of seven officers and 250 men. (42)

On 12th June, 1915, Attlee and his regiment was sent to Mesopotamia. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, had persuaded Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, and the British government to open up another front in order to free up a supply route to Russia and threaten Austria from the Balkans. Churchill's plan was to invade the Gallipoli peninsula, place a fleet of ships in the Sea of Marmara, putting Constantinople under threat, and force the Turkish government to sue for peace. (43)

Leaders of the Greek Army informed Kitchener that he would need 150,000 men to take Gallipoli. Kitchener rejected the advice and concluded that only half that number was needed. Kitchener sent the experienced British 29th Division to join the troops from Australia, New Zealand and French colonial troops on Lemnos. Information soon reached the Turkish commander, Liman von Sanders, about the arrival of the 70,000 troops on the island. Sanders knew an attack was imminent and he began positioning his 84,000 troops along the coast where he expected the landings to take place. (44)

The attack that began on the 25th April, 1915 established two beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe. Another major landing took place at Sulva Bay on 6th August. By this time they arrived the Turkish strength in the region had also risen to fifteen divisions. Attempts to sweep across the peninsula by Allied forces ended in failure. By the end of August the Allies had lost over 40,000 men. General Ian Hamilton asked for 95,000 more men, but although supported by Churchill, Lord Kitchener was initially unwilling to send more troops to the area. (45)

After arriving in Hellespont, Attlee and his troops prepared for a massive assault on Turkish positions. He found night watch duty particularly tedious and even attempted, as company commander, by trying to convert his officers to socialism. "It was very boring on night watch. The only way to keep awake was to get a good talk going with the sergeants. I remember a long discussion on industrial and craft unionism with my CSM of the NUR and the platoon sergeant of the NUVW. We agree very well." (46)

At the end of July, Attlee contracted dysentery and was carried unconscious to the beach to be embarked on a hospital ship and taken to Malta. He therefore missed the major assault that took place on 6th August, 1915. His regiment suffered enormous casualties. His company caught the worst of the attack. Five officers were killed and "a dozen or so" wounded. Attlee refused the offer of being sent back to England and insisted on rejoining his regiment. (47)

Attlee was back with his battalion in early October, Attlee found that the failure of the August assaults had drained all momentum from the campaign. As heavy rain and, later, snow made any operations difficult, his principal responsibility was to keep his men in shape. After one terrible blizzard over 5,000 men suffered from frostbite, with some on sentry duty found frozen stiff, their rifles still wedged in their hands. (48)

On 14th October, 1915, General Ian Hamilton was replaced by General Charles Munro. After touring all three fronts Munro recommended withdrawal. Lord Kitchener, initially rejected the suggestion but after arriving on 9th November 1915 he visited the Allied lines in Greek Macedonia, where reinforcements were badly needed. On 17th November, Kitchener agreed that the 105,000 men should be evacuated and put Munro in control as Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean. (49)

Attlee and its regiment were put on duty at the Suez Canal in January 1916, before being sent to Mesopotamia as part of a mission to relieve Major General Charles Townshend at Kut, south east of Baghdad. On 5th April, 1916, he carried a red flag to guide artillery fire, but was hit from behind in "friendly fire" and carried from the field. In subsequent attacks his troops suffered heavy casualties, and once more Attlee was fortuitously absent. Attlee was shipped to a hospital in Bombay. (50)

In a letter to his brother Tom, he explained what happened: "Just a line to let you know that I hope in a few days to be sailing for England... I shall not be sorry to leave the East... bullet through the left thigh and... a considerable hole in my right buttock... but I still can't move my legs at all. Something wrong with the transmitting apparatus, I suppose. It's most absurd. I send along a direct order to my leg to lift itself and it takes not the slightest notice... By the way, it may interest the comrades to know I was hurt while carrying the red flag to victory." (51)

Tom Attlee and Conscription

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. The British had suffered high casualties at the Marne (12,733), Ypres (75,000), Gallipoli (205,000), Artois (50,000) and Loos (50,000). The British Army found it difficult to replace these men. In May 1915 135,000 men volunteered, but for August the figure was 95,000, and for September 71,000. Asquith appointed a Cabinet Committee to consider the recruitment problem. Testifying before the Committee, David Lloyd George commented: "I would say that every man and woman was bound to render the services that the State they could best render. I do not believe you will go through this war without doing it in the end; in fact, I am perfectly certain that you will have to come to it." (52)

Lloyd George threatened to resign if Asquith did not introduce conscription (compulsory enrollment). Eventually he gave in and the Military Service Bill was introduced by Asquith on 21st January 1916. John Simon, the Home Secretary, resigned and so did Arthur Henderson, who had represented the Labour Party in the coalition government. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of the Daily News argued that Lloyd George was engineering the conscription crisis in order to substitute himself for Asquith as leader of the country. (53)

The Military Service Act specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called-up for military service unless they were widowed with children or ministers of religion. Conscription started on 2nd March 1916. The act was extended to married men on 25th May 1916. The following month Tom Attlee made an application for exemption to the Poplar Military Service Tribunal, on the grounds of his conscientious objection. On 18th October, he was offered non-combatant service, but he refused this, also on the grounds of his pacifist principles. An estimated 16,550 registered as conscientious objectors. (54)

Most conscientious objectors accepted non-combatant service, leaving only 1,300 absolutists willing, as Tom was, to "go the whole hog". He wrote to his sister: "War doesn't work: to kill one devil you can call up seven new ones... I think the growth of envy, hatred, malice, pride, vain-glory, hypocrisy and certainly all uncharitableness is enough to drive me crazy." (55) Attlee remained active in the peace movement. He was at a meeting with Sylvia Pankhurst at the gates of the London docks when they were attacked by supporters of the war and attempts were made to throw them in the Thames. (56)

In December, 1916, Tom Attlee learned that his appeal to the Military Service Tribunal had not been successful. He spent Christmas awaiting arrest, with his wife Kathleen pregnant with their second child. He was arrested on 22nd January and sent to Wormwood Scrubs, where he spent the first month in solitary confinement, forced to sleep on a plank and given only bread and water. (57)

Major Clement Attlee

By the end of 1916 Attlee had fully recovered his health and returned to his regiment. On 1st March 1917, he was promoted to major in the 5th Battalion of the South Lancashire Regiment and sent to Dorset. He became responsible for training and instructing new conscripts before they were sent to the Western Front. He spent two brief spells in France and Belgium - from 15th to 29th March 1917, and 10th to 24th September 1917, but did not take part in any military campaigns. At Ypres he witnessed "the hideous scar of no-man's land". It was the "abomination of desolation itself". (58)

In March 1918, Major Attlee was given an infantry regiment to train in Walney Island, Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria. He described the area as a "crude, modern, industrial inferno". He compared the land to that of what he had seen on the Western Front. "It was not much worse to my mind that the district round Wolverhampton and the stretch of country seen from the train between Wigan and Widnes". In the same language he had used to describe "no-man's land" he described Lancashire as "an abomination of desolation and crude ugliness". (59)

Attlee began to lose his Christian faith. He told his brother that during the war he drifted from agnosticism to atheism. He described the Church of England as "the blind leading the blind". (60) Attlee rejected religiously inspired pacifism. "I think your objection to taking life is fallacious, in that it is at times necessary to take life". He did not like the nature of war any more than Tom. But the scruples of conscience, he explained, "cannot weigh with me if the work has to be done." (61)

In May 1918, Major Attlee was sent back to the Western Front. He joined the 55th West Lancashire Division as they made their way into Artois in pursuit of the retreating Germans. While advancing towards the German lines at Lille, he was knocked unconscious and was carried from the battlefield. Evacuated to England, in November he celebrated the news of Germany's defeat in a hospital in Wandsworth. Just a few miles away sat his brother Tom in a prison cell. Ellen Attlee remarked, "I don't know which of these two sons I am more proud of." (62)

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography, As It Happened, Clement Attlee described his time at Oxford University.

Oxford was at that time predominately Conservative though there was a strong Liberal group, notably at Ballioli, which counted among its undergraduates such men as R. H. Tawney and William Temple, the future Archbishop, whose influence on socialist thought was in later years to be so great. Socialism was hardly spoken of, although Sidney Ball at St. John's and A.J. Carlyle, at University College, kept the light burning.

I was at this time a Conservative, but I did not take any active part in politics. I never belonged to any political club. Some of my friends were interested in the University Settlements - Oxford House and Toynbee Hall.

(2) In October 1905, Clement Attlee went to visit a boys' club at Stepney that was being supported by his old school, Haileybury College.

I became interested in the work and began making the journey from Putney to the club one evening a week. Soon my visits became more frequent. In 1907 the club manager resigned and Cecil Nussey asked me if I would take over the job. I agreed, went to live at Haileybury House and thus began a fourteen years' residence in East London.

I soon began to learn many things which had hitherto been unrevealed. I found there was a different social code. Thrift, so dear to the middle classes, was not esteemed so highly as generosity. The Christian virtue of charity was practised, not merely preached. I recall a boy in the club living in two rooms with his widowed mother. He earned seven shillings and sixpence a week. A neighbouring family, where there was no income coming in, were thrown on to the street by the landlord. The boy and his mother took them all into their little home.

I remember taking the club's football team by local train to play an away match. Young Ben had come straight from work with his week's money - a half-sovereign - and somehow he had lost the gold coin. There was no hesitation amongst the boys. Jack said, "Look, a tanner each all round will make half of it." They readily agreed, yet probably that tanner was all that most of them would have retained for themselves from their wages.

I found abundant instances of kindness and much quiet heroism in these mean streets. These people were not poor through their lack of fine qualities. The slums were not filled with the dregs of society. Not only did I have countless lessons in practical economics but there was kindled in me a warmth and affection for these people that has remained with me all my life.

From this it was only a step to examining the whole basis of our social and economic system, I soon began to realise the curse of casual labour. I got to know what slum landlordism and sweating meant. I understood why the Poor Law was so hated. I learned also why there were rebels.

(3) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

My elder brother, Tom, was an architect and a great reader of Ruskin and Morris. I too admired these great men and began to understand their social gospel. My brother was helping at the Maurice Hostel in the nearby Hoxton district of London. Our reading became more extensive. After looking into many social reform ideas - such as co-partnership - we both came to the conclusion that the economic and ethical basis of society was wrong. We became socialists.

I recall how in October, 1907, we went to Clements Inn to try and join the Fabian Society. Edward Pease, the Secretary, regarded us as if we were two beetles who had crept under the door, and when we said we wanted to join the Society he asked coldly, "Why?" We said, humbly, that we were socialists and persuaded him we were genuine.

I remember very well the first Fabian Society meeting we attended at Essex Hall. The platform seemed to be full of bearded men: Aylmer Maude, William Sanders, Sidney Webb and Bernard Shaw. I said to my brother, "Have we got to grow a beard to join this show. H. G. Wells was on the platform, speaking with a little piping voice; he was very unimpressive.

(4) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

In 1912, largely through the influence of Sidney Webb, I was appointed a lecturer and tutor in the London School of Economics in the Department of Social Science and Public Administration. I was not appointed on the score of academic qualifications but because I was considered to have a practical knowledge of social conditions. The salary was small but sufficient for my wants, while the hours of my work left me plenty of time for social work and also for socialist propaganda, for it was a fundamental rule of the School that no one could be restricted in venting his political opinions.

(5) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

The outbreak of the war brought great heart-searchings in the ranks of the Labour and Socialist Movement, especially in the membership of the Independent Labour Party, which had always been strongly pacifist. The difference of view in the Party was well illustrated in our family. My brother Tom was a convinced conscientious objector and went to prison. I thought it my duty to fight.

I was told when I first tried to join the Army that I was too old at thirty-one. A relative of one of my pupils, who was commanding a battalion of Kitchener's Army, had applied for me, and one Sunday morning, on returning from doing a guard at Lincoln's Inn, I found a letter telling me to report as a Lieutenant to the 6th South Lancashire Regiment at Tidworth. There I found plenty to do, as I soon found myself in temporary command of a company of seven officers and 250 men.

(5) Clement Attlee, Social Worker (1920)

In a civilized community, although it may be composed of self-reliant individuals, there will be some persons who will be unable at some period of their lives to look after themselves, and the question of what is to happen to them may be solved in three ways - they may be neglected, they may be cared for by the organized community as of right, or they may be left to the goodwill of individuals in the community...

Charity is only possible without loss of dignity between equals. A right established by law, such as that to an old age pension, is less galling than an allowance made by a rich man to a poor one, dependent on his view of the recipient's character, and terminable at his caprice.

References

(1) Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) page 5

(2) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 6

(3) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 30

(4) Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) page 5

(5) Trevor Burridge, Clement Attlee: A Political Biography (2005) page 11

(6) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 13

(7) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 37

(8) Frederick Webb Headley, Darwinism and Modern Socialism (1909)

(9) The Haileyburian (18th February, 1901)

(10) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 18

(11) Clement Attlee, Empire into Commonwealth (1961) pages 6-12

(12) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 13

(13) Peggy Attlee, A Quiet Conscience: Biography of Thomas Simons Attlee (1995) page 17

(14) Cyril Clemens, The Man from Limehouse: Clement Richard Attlee (1946) page 2

(15) The Guardian (22nd April, 1963)

(16) The Manchester Guardian (13th November, 1948)

(17) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954) pages 21-22

(18) R. C. Whiting, Clement Attlee : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2011)

(19) The Spectator (13th December, 1963)

(20) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 34

(21) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 50

(22) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 21

(23) Clement Attlee, Social Worker (1920) pages 211-212

(24) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 37

(25) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954) page 17

(26) Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) page 15

(27) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954) page 21

(28) Roy Jenkins, Mr. Attlee: An Interim Biography (1948) page 30

(29) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 60

(30) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954) pages 29-30

(31) Cyril Clemens, The Man from Limehouse: Clement Richard Attlee (1946) page 5

(31a) Kingsley Martin, The New Statesman (24 th April, 1954)

(32) R. C. Whiting, Clement Attlee : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2011)

(33) Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) page 16

(34) The Spectator (13th December, 1963)

(35) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 63

(36) Clement Attlee, Social Worker (1920) page 207

(37) R. C. Whiting, Clement Attlee : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2011)

(38) Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein, The Labour Party: A Marxist History (1988) page 43

(39) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 50

(40) Clement Attlee, As It Happened (1954) pages 55-56

(41) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 43

(42) Nicklaus Thomas-Symonds, Attlee: A Life in Politics (2012) pages 21-22

(43) Roy Jenkins, Churchill (2001) page 255

(44) Les Carlyon, Gallipoli (2001) pages 189-190

(45) Basil Liddell Hart, History of the First World War (1930) page 138

(46) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 49

(47) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (27th August, 1915)

(48) Alan Moorehead, Gallipoli (2007) page 328

(49) George Barrow, The Life of General Sir Charles Carmichael Monro (1931) page 65

(50) Michael Jago, Clement Attlee (2017) page 51

(51) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (19th April, 1916)

(52) John Grigg, Lloyd George, From Peace To War 1912-1916 (1985) pages 325-326

(53) Alfred George Gardiner, Daily News (22nd April, 1916)

(54) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 87

(55) Peggy Attlee, A Quiet Conscience: Biography of Thomas Simons Attlee (1995) page 67

(56) East London News and Chronicle (22nd November, 1916)

(57) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 87

(58) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (20th March, 1918)

(59) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 88

(60) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (20th March, 1918)

(61) Clement Attlee, letter to Tom Attlee (2nd April, 1918)

(62) Peggy Attlee, A Quiet Conscience: Biography of Thomas Simons Attlee (1995) page 66

John Simkin