On this day on 27th November

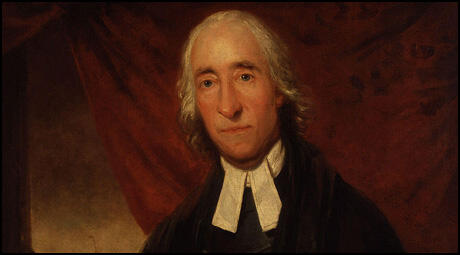

On this day in 1759 James Ramsay's vessel intercepted the British slave ship Swift. According to Ramsay's biographer, James Watt: "On boarding her, Ramsay found over 100 slaves wallowing in blood and excreta, a scene of human degradation which remained for ever in his memory and so distracted his attention that, on returning to his ship, he fell and fractured his thigh bone. It was the more serious of two such accidents and he remained lame for life. With an end to his naval service in prospect, Ramsay sought ordination in the Anglican church to enable him to work among slaves."

In July 1761, Ramsay left the navy and in November he was ordained by the Bishop of London. Soon afterwards he travelled to St Kitts. In 1763 he married Rebecca Akers, the daughter of a plantation owner on the island. Over the next few years they had four children. Ramsay was appointed surgeon to several sugar plantations and was shocked by the way the slaves were treated by the overseers. Ramsay later recalled: "At four o'clock in the morning the plantation bell rings to call the slaves into the field.... About nine o'clock they have half an hour for breakfast, which they take into the field. Again they fall to work... until eleven o'clock or noon; the bell rings and the slaves are dispersed in the neighbourhood to pick up natural grass and weeds for the horses and cattle (and to prepare and eat their own lunch)... At two o'clock, the bell summons them to deliver in their grass and to work in the fields... About half an hour before sunset they are again required to collect grass - about seven o'clock in the evening or later according to season - deliver grass as before. The slaves are then dismissed to return to their huts, picking up brushwood or dry cow dung to prepare supper and tomorrow's breakfast. They go to sleep at about midnight."

Richard Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has pointed out: "Ramsay's evangelical brand of Christianity brought him immediately into conflict with West Indian planters who were appalled that he insisted on racially integrating his religious services. He also carried out missionary activities among enslaved Africans, which brought him into further conflict with the white West Indian authorities." The planters were always suspicious of any social action amongst Africans and they quickly turned against Ramsay, accusing him of everything from seditious preaching to serial philandering."

Ramsay was particularly concerned about slave punishments: "The ordinary punishments of slaves, for the common crimes of neglect, absence from work, eating the sugar cane, theft, are cart whipping, beating with a stick, sometimes to the breaking of bones, the chain, an iron crook about the neck... a ring about the ankle, and confinement in the dungeon. There have been instances of slitting of ears, breaking of limbs, so as to make amputation necessary, beating out of eyes, and castration... In short, in the place of decency, sympathy, morality,and religion; slavery produces cruelty and oppression. It is true, that the unfeeling application of the ordinary punishments ruins the constitution, and shortens the life of many a poor wretch."

On his return to Britain in 1777 he became friends with Admiral Charles Middleton at Barham Court, Teston, Kent. His stories about life on a slave plantation helped Middleton and his wife to be opponents of the slave trade. In April 1778 he rejoined the navy as chaplain to Admiral Samuel Barrington on the West Indies Station. During this period he wrote Sea Sermons for the Royal Navy (1781).

In January 1782, Ramsay was appointed as vicar of Teston and rector of Nettlestead. He also acted as Middleton's confidential secretary. Ramsay's Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies appeared in 1784. This book inspired a generation of anti-slavery campaigners. Thomas Clarkson argued that as a result of Ramsay book the "first controversy ever entered into on the subject, during which, as is the case in most controversies, the cause of truth was spread."

Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005), argued: "Almost everything else written against slavery was... a mixture of biblical citations, philosophical argument, and second-hand accounts. Ramsay, by contrast, offered a searing eyewitness picture. He vividly described beatings he had seen; he told of weary slaves carrying cane to the mill by moonlight, and how new mothers had to bring their babies to the fields, leaving them in furrows exposed to the sun and rain."

Ramsay was attacked in the press and one plantation owner from St Kitts, Crisp Molyneux, Ramsay's character and professional reputation. As Richard Reddie pointed out: "The planters were always suspicious of any social action amongst Africans and they quickly turned against Ramsay, accusing him of everything from seditious preaching to serial philandering." Although Olaudah Equiano, an emancipated slave, confirmed all that Ramsay had written, he never recovered from this attack.

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as Ramsay, William Allen, John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, John Cartwright, Charles Middleton and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Hoare reported subscriptions of £136.

Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and he required an intellectual walking stick."

On 12th May 1789 William Wilberforce made his first speech on the subject. Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has pointed out: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance".

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying."

James Ramsay was now extremely ill. He wrote to his friend Thomas Clarkson on 10th July 1789: "Whether the bill goes through the House or not, the discussion attending it will have a most beneficial effect. The whole of this business I think now to be in such a train as to enable me to bid farewell to the present scene with the satisfaction of not having lived in vain." Ten days later Ramsay died from a gastric haemorrhage.

James Watt has argued: "His enemies acknowledged his exemplary qualities, while deploring the intemperate language of his books; and the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807 probably owed more to James Ramsay's personal integrity, ethical arguments, and constructive proposals than to any other influence."

On this day in 1809 Fanny Kemble, the daughter of the actors Charles and Marie Kemble, was born in London. She made her first appearance on the stage when she appeared as Juliet in her father's production of Romeo and Juliet on 5th October, 1829. Fanny was a great success and this role was followed by several others in her father's Covent Garden Theatre.

The theatre was £13,000 in debt when Kemble started her career as an actress but she was so popular than within a short period it was back in profit. Fanny had a sparkling personality and she soon had several elderly admirers including Thomas Macaulay and George Stephenson, who invited her to the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Kemble later wrote: "The most intense curiosity and excitement prevailed, and though the weather was uncertain, enormous masses of densely packed people lined the road, shouting and waving hats and handkerchiefs as we flew by them. We travelled at 35 miles an hour (swifter than a bird flies). When I closed my eyes this sensation of flying was quite delightful.... I had been unluckily separated from my mother in the first distribution of places, but by an exchange of seats which she was enabled to make she rejoined me when I was at the height of my ecstasy, which was considerably damped by finding that she was frightened to death, and intent upon nothing but devising means of escaping from a situation which appeared to her to threaten with instant annihilation herself and all her travelling companions."

In 1833 Fanny Kemble toured America with her father. While in New York she met and married Pierce Butler, a southern planter. Fanny gave up acting for a while but after their divorce in 1848 she returned to the stage. As well as appearing in plays, Fanny gave Shakespearean readings.

Kemble retired to Lennox, Massachusetts, where she wrote several autobiographical works including Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation (1863), Record of a Childhood (1878) and Records of Later Life (1882). Fanny Kemble died in London on 15th January, 1893 and five days later was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery.

On this day in 1874 American historian, Charles Beard, was born. As a student he joined the Hull House social settlement in Chicago. After graduating from DePauw University, he studied at Oxford University (1898-1900) and while in England he helped establish Ruskin Hall, a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people.

Beard met Mary Ritter while at DePauw University together. The couple married in the United States in 1900 before moving back to England. The Beards lived in Oxford and Manchester, where they became close friends of Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. At the time the women were members of the socialist reform group, the Independent Labour Party. They were also active in the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) but later formed the more militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Beard returned to the United States in 1904 to teach history at Columbia University. Beard and his wife were involved in several progressive political campaigns including women's suffrage and an end to child labour. During this period he was a regular contributor to the journal, the New Republic.

Charles Beard became a well-known academic figure with his book An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913). In the book he controversially argued that those men who had drafted the American Constitution acted more on economic motives than for abstract ideals. He followed this with The Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915). During this period Beard developed the idea that for historians "objectivity was a noble dream". Instead, Beard believed that his role as a historian was to "provide the tools for progressive social change".

A Quaker, Beard was involved in the campaign to keep the United States out of the First World War. In 1917 he resigned from Columbia University in protest against the Espionage Act.

During the Red Scare in 1919, Archibald Stevenson of Military Intelligence, leaked a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" to the press. This list included the names of Beard, Jane Addams, Lillian Wald and Oswald Garrison Villard. It was also revealled that these people had been under government surveillance for many years.

Beard was never able to secure an academic appointment again and was forced to live off his writings and a diary farm he owned in Connecticut. Working with his wife, Mary Ritter Beard, he wrote a two volume history of the United States, The Rise of American Civilization (1927). This was followed by America in Midpassage (1939) and The American Spirit (1942). The couple also collaborated on A Basic History of the United States (1944).

Although a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, he was very critical of his foreign policy. This was reflected in his books, American Foreign Policy in the Making: 1932-1940 (1946) and President Roosevelt and the Coming of War (1948). Charles Beard died in New Haven, Connecticut, on 1st September, 1948.

On this day in 1878 the artist William Orpen was born. Orpen showed an early interest in drawing and according to his biographer this "was indulged by his mother, who supported his wish to go to art school against her husband's desire that he should study law and enter the family firm."

Orpen entered the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin at the age of thirteen. During his years at the school Orpen won every major prize available. He then enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1897. His main tutors were Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer. Orpen's fellow students included Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis. Spencer Gore, Michel Salaman, Edna Waugh, and Herbert Barnard Everett.

Initially, Orpen wanted to be a caricaturist but after having several cartoons rejected by Punch Magazine he decided to return to Ireland to teach at the Dublin School of Art. He returned to London in 1903 where he joined forces with Augustus John to run a short-lived art school in Chelsea. In 1906 he also helped to set up the Chenil Gallery with his brother-in-law, Jack Knewstub.

In 1908 William Orpen exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy. This helped to develop his reputation as a portrait painter. In 1916 Orpen's friend, the Quartermaster General, John Cowans, arranged for him to receive a commission in the Army Service Corps. This mainly involved him painting the portraits of senior political and military figures such as Winston Churchill and Lord Derby.

In early 1917, Charles Masterman, head of the government's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB) recruited Orpen to produce paintings of the Western Front. His biographer, Bruce Arnold, points out: "He left for France in April 1917, and for the next four years was totally immersed in the war and its aftermath. His output, and its overall excellence, makes him the outstanding war artist of that period, possibly the greatest war artist produced in Britain. Analysis of his war work, the major part of which is in the Imperial War Museum, London, shows a development in style and understanding, from the idealism which inspired him when he first arrived at the front to the disillusionment with the terrible ending to the war, and then the further dismay he and many felt at the direction taken by the peace deliberations. His paintings of the Somme battlefields are haunting recollections of anguish and chaos, of ruined landscapes baked in the summer sun, the torn ground white and rocky, the debris of the dead scattered and ignored."

While in France he painted portraits of Sir Douglas Haig, Hugh Trenchard, Herbert Plumer, Henry Rawlinson, Henry Wilson, James McCudden, Arthur Rhys-Davids, Reginald Hoidge, John Edward Seely, John Cowans, Adrian Carton de Wiart, and Ferdinand Foch. Orpen was shocked by what he saw at the front and also painted pictures such as Dead Germans in a Trench. Other paintings such as The Mad Woman of Douai, "convey the stress and anguish he certainly felt about the war and its aftermath".

Orpen was commissioned to paint portraits of the politicians at the Versailles Peace Conference. He also produced a series of caricatures that according to the author of the Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Cartoonists and Caricaturists (2000) "were widely admired". Orpen believed that the soldiers that fought in the war were betrayed by the politicians at Versailles. Instead of the portraits he painted To the Unknown British Soldier in France. The original painting showed the draped coffin flanked by two shell-shocked soldiers standing guard. There was such an outcry when it was exhibited in 1919 that Orpen was forced to paint out the soldiers. However, as one critic has pointed out "their shadowy forms remaining as ghostly pentimento."

Orpen wrote about his experiences in the First World War in An Onlooker in France (1921). Bruce Arnold has argued: "His outspokenness became controversial. His standing as a painter gave him the ear of many people in power, and he took risks, confronting what he saw as foolishness.... His own personality had developed with the war; his early idealism became a form of sombre realistic recognition of the terrible path of war through the lives of a whole generation. He came to love the fighting man, and to despise the politicians, with their glib words and their self-interested carve-up of Europe which was subsequently to prove so disastrous."

An exhibition of Orpen's war paintings were well received. Arnold Bennett argued: "William Orpen, having discovered a new subject, composes it newly.... Landscape, shell-holes, ruined trees and buildings, dug-outs, tents, and the tragedy and comedy of human existence - he see them as though nobody had ever seen them before; and he arranges them in fresh patterns of contour, colour, plane. His ingenuity in manipulating the material is simply endless, and yet he is never tempted to falsify the material."

William Orpen became known for his portraits of public figures and during his career produced over 600 of these pictures. Mark Bryant has pointed out: "However, though he was financially very successful in his main occupation as a portrait painter (reputedly earning more than £54,000 in 1929 alone) his technique of using photographs as an aid did not meet with universal approval."

Sir William Orpen died from liver and heart failure on 29th September 1931 at his home in South Kensington. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery.

On this day in 1886 Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary about meeting Annie Besant. "I am sorry I have not seen Mrs Besant again. We met and I felt interested in that powerful woman, with her blighted wifehood and motherhood and her thirst for power and defence of the world. I heard her speak, the only woman I have ever known who is a real orator, who has the gift of public persuasion. But to see her speaking made me shudder. it is not womanly to thrust yourself before the world."

On the day in 1921 Alexander Dubcek was born in Slovakia. When he was a child his family moved to the Soviet Union. He returned to Czechoslovakia on the outbreak of the Second World War and as a member of the Communist Party fought in the resistance movement against the German Army.

After the war Dubcek gradually rose in the party hierarchy and eventually became secretary of the Slovak Communist Party. In the early 1960s the country suffered an economic recession. Antonin Novotny, the president of Czechoslovakia, was forced to make liberal concessions and in 1965 he introduced a programme of decentralization. The main feature of the new system was that individual companies would have more freedom to decide on prices and wages.

These reforms were slow to make an impact on the Czech economy and in September 1967, Dubcek presented a long list of grievances against the government. The following month there were large demonstrations against Novotny.

In January 1968 the Czechoslovak Party Central Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Antonin Novotny and he was replaced by Dubcek as party secretary. Gustav Husak, a Dubcek supporter, became his deputy. Soon afterwards Dubcek made a speech where he stated: "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness."

During what became known as the Prague Spring, Dubcek announced a series of reforms. This included the abolition of censorship and the right of citizens to criticize the government. Newspapers began publishing revelations about corruption in high places. This included stories about Novotny and his son. On 22nd March 1968, Novotny resigned as president of Czechoslovakia. He was now replaced by a Dubcek supporter, Ludvik Svoboda.

In April 1968 the Communist Party Central Committee published a detailed attack on Novotny's government. This included its poor record concerning housing, living standards and transport. It also announced a complete change in the role of the party member. It criticized the traditional view of members being forced to provide unconditional obedience to party policy. Instead it declared that each member "has not only the right, but the duty to act according to his conscience."

The new reform programme included the creation of works councils in industry, increased rights for trade unions to bargain on behalf of its members and the right of farmers to form independent co-operatives.

Aware of what happened during the Hungarian Uprising Dubcek announced that Czechoslovakia had no intention of changing its foreign policy. On several occasions he made speeches where he stated that Czechoslovakia would not leave the Warsaw Pact or end its alliance with the Soviet Union.

In July 1968 the Soviet leadership announced that it had evidence that the Federal Republic of Germany was planning an invasion of the Sudetenland and asked permission to send in the Red Army to protect Czechoslovakia. Dubcek, aware that the Soviet forces could be used to bring an end to Prague Spring, declined the offer.

On 21st August, 1968, Czechoslovakia was invaded by members of the Warsaw Pact countries. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Czech government ordered its armed forces not to resist the invasion. Alexander Dubcek and Ludvik Svoboda were taken to Moscow and after meetings with Leonid Brezhnev and Alexsei Kosygin announced that after "free comradely discussion" that Czechoslovakia would be abandoning its reform programme.

In April 1969 Dubcek was replaced as party secretary by Gustav Husak. The following year he was expelled from the party and for the next 18 years worked as a clerk in a lumber yard in Slovakia.

After the collapse of communism government in November 1989, Dubcek was elected chairman of the Federal Assembly. He was awarded the Sakharov Peace Prize and his book, The Soviet Invasion, was published in 1990. This was followed by his autobiography, Hope Dies Last. Alexander Dubcek died as a result of a car accident in 1992.

On this day in 1936 Agnes Hodgson writes about being a nurse in the Spanish Civil War. Hodgson was born in Melbourne on 5th August, 1906. Her father, William Hodgson, a commercial traveller, had been killed at Gallipoli and when her mother died in 1920, she was sent to Scotland to live with relatives.

At the age of 15 Agnes returned to Australia and became a boarder at Presbyterian Ladies College in Melbourne. She was determined to become a nurse and in 1925 she began her training at Alfred Hospital. In 1928 she graduated as a Registered Nurse with a specialty in pediatrics.

Agnes decided to find work as a nurse abroad. After nursing in Budapest she took up an appointment at the Anglo-American Hospital in Rome. In the summer of 1932 she made a long trip through Spain and North Africa. According to her biographer, Judith Keene: "In mid 1933 Agnes returned to Australia an experienced and cultivated woman, speaking fluent Italian, with a passion for travel, and a great yen for worthwhile and interesting work."

For the next couple of years Agnes Hodgson worked on her brother's farm in Tasmania and nursing private patients in Melbourne. However, she still had a great desire for travel and adventure and contemplated volunteering to nurse in Abyssinia during the invasion order by Benito Mussolini.

In August 1936 the Australian Spanish Relief Committee decided to send a medical aid unit caring for Republican wounded during the Spanish Civil War. This included sending four nurses from Australia. Hodgson applied and was accepted and in October 1936 she travelled from Sydney to Barcelona on the Oransay with Mary Lowson, May Macfarlane and Una Wilson. Wilson told reporters shortly before sailing: "If we get captured or shot that's that. It's only a few years off your life and its better than spending all your days in a private hospital. Danger is the spice of life, that and the feeling that we'll be doing something with real meaning."

Agnes Hodgson, unlike the other three nurses, who were all members of the Communist Party of Australia, she was not a left-wing political activist. Mary Lowson was especially critical of Hodgson's liberal views. Judith Keene has argued: "Although Agnes had little time for Mussolini and fascism, she had been seduced by Italian culture, the warmth of Italian people, and the joys of an Italian lifestyle while living in Italy. Mary, on the other hand, was a dedicated communist committed to the long haul to the proletarian revolution."

The Oransay arrived at Toulon at the end of November. They were met by the Toulon Movement Against the War. A public meeting was held by supporters of the Popular Front government in Spain and as the four women were announced and walked towards the stage the crowded hall sang the Internationale.

The women arrived in Barcelona on 1st December 1936. Mary Lowson immediately informed Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit and Hugh O'Donnell, administrators for British Medical Aid Unit, that Agnes Hodgson was a fascist who she considered was spying on behalf of the Nationalists. She was immediately called in for questioning by the Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya (PSUC). May Macfarlane and Una Wilson complained to Lowson about how their colleague was being treated. They claimed they would return to Australia if anything happened to Hodgson. Writing later to the Australian Spanish Relief Committee about Lowson's behaviour, she admitted that she feared "they would be bumped off."

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, who was also a non-communist, protected Agnes Hodgson from harm. On 2nd December 1936 she wrote in her diary: "I had lunch with Mr Loutit from BMAU. He took me to a Catalan restaurant where we ate well - but much garlic flavoured food. He drank wine, pouring it into his mouth out of a special Spanish vessel - very skilful proceeding. We talked a bit then went for coffee up on a hill, his chauffeur coming with us. Lovely view of hills and harbour. Sun setting - looked at destroyers and foreign sloops outside port - saw a seaplane arriving on the water. Returned to the British Medical Aid Unit's flat to await other colleagues. Had tea and met other members of BMAU down on leave - one played the piano and tuned his violin. Danced a little with Mr Loutit dancing in gum-boots."

While in Barcelona she met Anna Louise Strong and Hodgson attended the funeral of Hans Beimler. She wrote in her diary: "Marched in the funeral procession of Hans Beimler, an ex-German Communist deputy who was killed fighting at the front here. A man very able and evidently much loved, it was a great loss to the party. An English party was joining the procession so Lowson offered us to join in. We assembled outside the Karl Marx building, and waited there until all were ready. Lowson carried flowers, and we all joined in with the women's brigade - international women, English, German and Swiss."

Eventually, Mary Lowson, May Macfarlane and Una Wilson travelled to the International Brigade hospital near Albacete. Hodgson was left behind in Barcelona. Lowson, after a few weeks working at the hospital returned to the city where she was attached to the English Section of the Republican Information Service which produced propaganda for the Popular Front government in Spain.

Hodgson was given work in a small clinic in Barcelona. After a full investigation into the spying charges she was allowed to work with the British Medical Aid Unit established by Kenneth Sinclair Loutit at Grañén near Huesca on the Aragon front. At first things were quiet but after four months the major Aragon offensive began.

On 20th April 1937 she wrote in her diary: "Another busy day. A German's leg amputated during the night... the German had been seven days without food, and his leg was alive with maggots as he had been lying among the fascist wounded. We have had about a dozen fascist wounded prisoners here, treated exactly as other patients, to their astonishment. Also officials who interviewed them questioned them politely. Later in the day a fair number of wounded were brought in from the Carlos Marx battalion. A lung case and one with 11 perforations in the abdomen were admitted to the ward. A very busy day. The Political Commissar, on the eighth day after his perforated stomach, began vomiting and hemorrhaging. A very bad patient, possibly his own fault, as he drank water from the ice bag. He has been given blood transfusions and all manner of things but he will probably die."

In October 1937 Hodgson returned to Barcelona where she had a meeting with Leah Manning and Peter Spencer. "Met Leah Manning and Peter Spencer Churchill and they suggested my going to a new hospital near Madrid. I was almost decided for it then heard from Esther about various intrigues that go on there, etc. so decided to stick to my plan of going to England. Leah Manning said if I decided later to come back to let her know."

In January 1938 Hodgson arrived back in Australia. She told a reporter: "Never have I seen such dreadful wounds and suffering as those that result from warfare. What I have seen in Spain has made me a militant pacifist for ever."

Over the next few months she travelled into the northern Australian outback. After a short spell as house mistress at Sydney Church of England Girls' Grammar School she found employment working as a journalist for the Australian Daily Telegraph.

During the Second World War Hodgson became the head of the Tasmanian division of the Australian Women's Land Army. In January 1944 she married Ralph Tonkin, an officer in the Australian Army. The couple had two children, Rachel and Ian.

Agnes Hodgson Tonkin died in June 1984. Her Spanish diary, edited by Judith Keene, was published as a book, The Last Mile to Huesca: An Australian Nurse in the Spanish Civil War in 1988.

Aileen Palmer in Barcelona in December 1936.