Alexander Dubcek

Alexander Dubcek was born in Slovakia in 1921. When he was a child his family moved to the Soviet Union. He returned to Czechoslovakia on the outbreak of the Second World War and as a member of the Communist Party fought in the resistance movement against the German Army.

After the war Dubcek gradually rose in the party hierarchy and eventually became secretary of the Slovak Communist Party.

In the early 1960s the country suffered an economic recession. Antonin Novotny, the president of Czechoslovakia, was forced to make liberal concessions and in 1965 he introduced a programme of decentralization. The main feature of the new system was that individual companies would have more freedom to decide on prices and wages.

These reforms were slow to make an impact on the Czech economy and in September 1967, Dubcek presented a long list of grievances against the government. The following month there were large demonstrations against Novotny.

In January 1968 the Czechoslovak Party Central Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Antonin Novotny and he was replaced by Dubcek as party secretary. Gustav Husak, a Dubcek supporter, became his deputy. Soon afterwards Dubcek made a speech where he stated: "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness."

During what became known as the Prague Spring, Dubcek announced a series of reforms. This included the abolition of censorship and the right of citizens to criticize the government. Newspapers began publishing revelations about corruption in high places. This included stories about Novotny and his son. On 22nd March 1968, Novotny resigned as president of Czechoslovakia. He was now replaced by a Dubcek supporter, Ludvik Svoboda.

In April 1968 the Communist Party Central Committee published a detailed attack on Novotny's government. This included its poor record concerning housing, living standards and transport. It also announced a complete change in the role of the party member. It criticized the traditional view of members being forced to provide unconditional obedience to party policy. Instead it declared that each member "has not only the right, but the duty to act according to his conscience."

The new reform programme included the creation of works councils in industry, increased rights for trade unions to bargain on behalf of its members and the right of farmers to form independent co-operatives.

Aware of what happened during the Hungarian Uprising Dubcek announced that Czechoslovakia had no intention of changing its foreign policy. On several occasions he made speeches where he stated that Czechoslovakia would not leave the Warsaw Pact or end its alliance with the Soviet Union.

In July 1968 the Soviet leadership announced that it had evidence that the Federal Republic of Germany was planning an invasion of the Sudetenland and asked permission to send in the Red Army to protect Czechoslovakia. Dubcek, aware that the Soviet forces could be used to bring an end to Prague Spring, declined the offer.

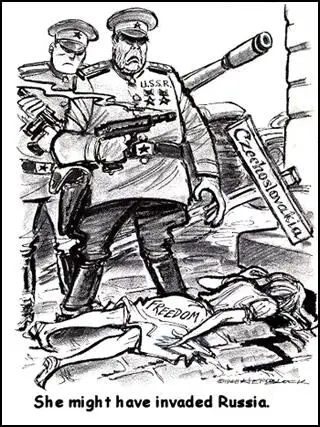

On 21st August, 1968, Czechoslovakia was invaded by members of the Warsaw Pact countries. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Czech government ordered its armed forces not to resist the invasion. Dubcek and Ludvik Svoboda were taken to Moscow and after meetings with Leonid Brezhnev and Alexsei Kosygin announced that after "free comradely discussion" that Czechoslovakia would be abandoning its reform programme.

In April 1969 Dubcek was replaced as party secretary by Gustav Husak. The following year he was expelled from the party and for the next 18 years worked as a clerk in a lumber yard in Slovakia.

After the collapse of communism government in November 1989, Dubcek was elected chairman of the Federal Assembly. He was awarded the Sakharov Peace Prize and his book, The Soviet Invasion, was published in 1990. This was followed by his autobiography, Hope Dies Last (1992).

Alexander Dubcek died as a result of a car accident in 1992.

Primary Sources

(1) Alexander Dubcek, Hope Dies Last (1992)

Spring and summer 1942 was probably the worst period of internal terror in Slovakia. It was also the time of mass deportation of Slovak Jews to the extermination camps in Poland. Between March and October that year, 58,000 were forcibly sent to Auschwitz and other camps; most of them never returned. Slovak prisons, too, were full of political opponents, among them hundreds of Communists.

The Slovak Communist Party was hard hit again in April 1943, when the whole fourth illegal leadership group was arrested, together with eighty leading functionaries. The Moscow leadership of the Czechoslovak Communist Party then sent to Slovakia two instructors, one of whom, Karol Smidke, formed the fifth and last underground Central Committee in the summer of 1943.

After Barbarossa and Pearl Harbor, the war tide slowly turned against the Axis. In August and September 1942, Britain and the French government in exile declared the Munich Pact invalid, and soon afterwards the Czechoslovak government in London was recognized by all three principal Allies - the USSR, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In February 1943, Germany lost the battle of Stalingrad, and the Western Allies soon landed in Italy. In Slovakia, as in other parts of German-dominated Europe, hope was rising again.

(2) Alexander Dubcek, Hope Dies Last (1992)

The Action Program did not even touch on the possibility of an independent initiative in foreign policy; for now this was a secondary issue. It focused entirely on domestic problems, political, economic, or cultural. Even in these areas, however, the Soviets had been accustomed to meddle. It was obvious that they were not happy that the program had been composed without their advice and consent.

The program declared an end to dictatorial, sectarian, and bureaucratic ways. It said that such practices had created artificial tension in society, antagonizing different social groups, nations, and nationalities. Our new policy had to be built on democratic cooperation and confidence among social groups. Narrow professional or other interests could no longer take priority. Freedom of assembly and association, guaranteed in the constitution but not respected in the past, had to be put into practice. In this sphere, there were to be no extralegal limitations.

The program proclaimed a return to freedom of the press and proposed the adoption of a press law that would clearly exclude prepublication censorship. Opinions expressed in mass communications were to be free and not be confused with official government pronouncements.

Freedom of movement was to be guaranteed, including not only citizens' right to travel abroad but their right to stay abroad at length, or even permanently, without being labeled emigrants. Special legal norms were to be established for the redress of all past injustices, judicial as well as political.

Looking toward a new relationship between the Czechs and the Slovaks, there was to be a federalization of the Republic, full renewal of Slovak national institutions, and compensatory safeguards for the minority Slovaks in staffing federal bodies.

In the economic sphere, the program demanded thorough decentralization and managerial independence of enterprises, as well as legalization of small-scale private enterprise, especially in the service sector.

This proposal, I should say, was immediately viewed by the Soviets as the beginning of a return to capitalism. Brezhnev made this accusation directly during one of our conversations in the coming months. I responded that we needed a private sector to improve the market situation and make peoples lives easier. Brezhnev immediately snapped at me, "Small craftsmen? We know about that! Your Mr. Bata used to be a little shoemaker, too, until he started up a factory!" Here was the old Leninist canon about small private production creating capitalism "every day and every hour." There was nothing one could do to change the Soviets' dogmatic paranoia.

Neither my allies nor I ever contemplated a dismantling of socialism, even as we parted company with various tenets of Leninism. We still believed in a socialism that could not be divorced from democracy, because its essential rationale was social justice. We also believed that socialism could function better in a market-oriented environment, with significant elements of private enterprise. Many legitimate forms of ownership, mainly cooperative and communal, had not been used to any effective extent mainly because of the imposition of Stalinist restrictions.

(3) Statement issued by Alexander Dubcek's government on 21st August, 1968.

Yesterday, August 20, 1968, around 11:00 p.m., the armies of the Soviet Union, of the Polish People's Republic, of the German Democratic Republic, the Hungarian Peoples Republic, and the Bulgarian Peoples Republic crossed the borders of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It happened without the knowledge of the President of the Republic, of the Chairman of the National Assembly, of the Prime Minister and of the First Secretary of the Central Committee of CPCz, and of all these organs.

The Presidium of the Central Committee of the CPCz was meeting in these hours and was discussing the preparations for the Fourteenth Party Congress. The Presidium appeals to all citizens of our Republic to keep calm and not to resist the armed forces moving in. Therefore neither our army, security forces or the People's Militias have been ordered to defend the country.

The Presidium believes that this act contradicts not only all principles of relations between socialist countries but also the basic norms of international law.

All leading officials of the state, of the CPCz and of the National Front remain in their functions, to which they were elected as representatives of the people and of the members of their organizations, according to the laws and other statutes valid in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic.

Constitutional officials convene for immediate session the National Assembly and the government of the Republic, and the Presidium of the CPCz convenes a plenary meeting of the Central Committee of the CPCz to deal with the situation.

(4) Alexander Dubcek, Hope Dies Last (1992)

The main door flew open again and in walked some higher officers of the KGB, including a highly decorated, very short colonel and a Soviet interpreter I had met before somewhere; I think he had been in Prague a few weeks earlier with Marshal Yakubovsky. The little colonel quickly reeled off a list of all Czechoslovak Communist Party officials present and told us that he was taking us "under his protection." Indeed we were protected, sitting around that table - each of us had a tommy gun pointed at the back of his head.

I was delivered to the Kremlin around 11:00 p.m. Moscow time, on Friday, August 23. My watch had stopped somewhere in the Subcarpathians, so I had only a vague idea of what time it was. Today, however, I can reconstruct a rather accurate chronology of those days based on documents and testimony.

In the Kremlin, they gave me no time to wash away the dust and dirt of the previous three days. They led me directly to "a meeting," as one of the KGB men called it. I remember a tall door, an antechamber behind it, another door, and then a large office with a rectangular table. There I saw the four men most responsible for the criminal invasion of my country: Brezhnev, Kosygin, Podgorny, and Voronov.

(5) Discussion that took place in Moscow between Alexander Dubcek and Leonid Brezhnev in August 1992.

Leonid Brezhnev: Lets agree not to bury ourselves in the past, but to discuss calmly, proceeding from the situation that has developed, in order to find a solution that will work to the benefit of the Czechoslovak Communist Party so that it can act, normally and independently along the lines laid down by the Bratislava Declaration Let it be independent. We don't want and we're not thinking of further intervention. And let the leadership work according to the principles of the January and May plenary sessions of the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. We have said this in our reports and we're prepared to affirm it again. Of course, we can't say that you re in a good mood. But your moods aren't the point. We must sensibly and soberly direct our talks toward the search for a solution. It can be stated flatly that the failure to carry out fixed obligations impelled five countries to extreme and inevitable measures. The sequence of events that has materialized confirms entirely that behind your back (by no means do we wish to say that you were at the head of it) right-wing powers (we will simply call them antisocialist) prepared both the congress and its actions. Underground stations and arms caches have now come to light. All of this has now come out. We don't want to raise claims against you personally, that you're guilty. You might not even have been aware of it; the right-wing powers are broad enough to have organized it all 'We would like to find the most acceptable solutions that will serve to stabilize the country, normalizing a workers' party without links to the right and normalizing a workers' government free from those links.

We don't need to conceal from each other that if we find the best solution we will still need time for normalization. No one should have the illusion that everything will all of a sudden become rosy. But if we do find the correct solution, then time will pass and every day will bring us successes, material talks and contacts will begin, the odor will dissipate, and propaganda and ideology will start to work normally. The working class will understand that, behind the backs of the Central Committee and the government leadership, right-wingers were preparing to transform Czechoslovakia from a socialist into a bourgeois republic. All that is clear now. Talks on economic and other matters will begin. The departure of troops, et cetera, will begin according to material principles. We have not occupied Czechoslovakia, we do not intend to keep it under "occupation," but we hope for her to be free and to undertake the socialist cooperation that was agreed upon in Bratislava. It is on that basis that we want to talk with you and find a workable solution. If need be, with Comrade Cernik as well. If we stay silent we will not improve the situation and will not spare the Czech, Slovak, and Russian peoples from tension. And with every passing day the right-wingers will fire up chauvinistic emotions against every socialist country, and first of all against the Soviet Union. Under such circumstances it would be impossible to pull out the troops; it's not to our advantage. It is on these grounds, on this basis, that we would like to conduct the talks, to see what you think, what's the best way to act. We're ready to listen. We have no diktat; let's look for another option together.

And we would be very grateful to you if you freely expressed different options, not just to be contrary, but to calmly find the proper option. We consider you an honorable communist and socialist. In Cierna you were unlucky, and there was a breakdown. Let's cast everything that happened aside. If we start asking which one of us was right, it will lead nowhere. But let's talk on the basis of what is, and under these conditions we must find a way out of the situation, what you're thinking and what we must do.

Alexander Dubcek: It's hard for me, given the trip and my bitter mood, to explain immediately my opinion about why we must reach a solution about the real situation that has arisen. Comrades Brezhnev, Kosygin, Podgorny, and Voronov, I don't know what the situation is at home. In the first day of the Soviet Army's arrival, I and the other comrades were isolated and then found ourselves here, not knowing anything. ... I can only conjecture what could have happened. In the first moments, the members of the Presidium who were with me at the Secretariat were taken to the Party Central Committee under the control of Soviet forces. Through the window I saw several hundred people gathered around the building, and you could hear what they were shouting: "We want to see Svoboda!" "We want to see the president!" "We want Dubcek!" I heard a number of slogans. After that there were shots. It was the last thing I saw. From that point on I know nothing, and can't imagine what's happening in the country and in the Party.

As a Communist who bears a great responsibility for recent events, I am sure that - not only in Czechoslovakia but in Europe, in the whole Communist movement - this action will cause us the bitterest consequences in the breakdown of, and bitter dissension within, the ranks of Communist parties in foreign countries, in capitalist countries.

Thus the matters at hand and the situation are, it seems to me very complex, although today was the first time I read the newspapers. I can only say, think of me what you will, I have worked for thirty years in the Party, and my whole family has devoted everything to the affairs of the Party, the affairs of socialism. Let whatever is going to happen to me happen. I'm expecting the worst for myself and I'm resigned to it.