On this day on 16th June

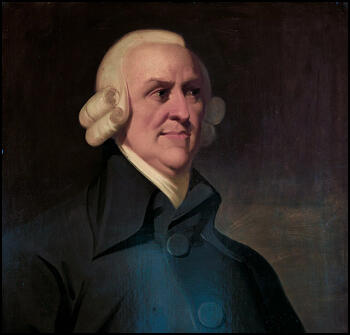

On this day in 1723 Adam Smith is born in Kirkcaldy, Scotland. He was educated at Glasgow University and Oxford University. In 1751 he was appointed as professor of logic at Glasgow and of moral philosophy the following year. His lectures covered the fields of ethics, rhetoric, jurisprudence and political economy.

Smith formed a close friendship with the moral philosopher, David Hume. In 1759 Smith published a Theory of Moral Sentiments, based on the ideas developed by Hume. His book attempted to explain how human communication depends on sympathy between the individual and other members of society.

Smith was appointed as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch in 1763. The two men lived in France but when Buccleuch died in Paris in 1766 Smith returned to London and the following year he was elected to the Royal Society.

Smith wrote a moving account of David Hume's death in 1776. Later that year he published his best-known work, Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. The book was an attempt to trace the historical development of industry and commerce in Europe. Smith examined the consequences of economic freedom and argued that it was the division of labour, rather than land or money, that was the main ingredient of economic growth. As he explained: "Every man is rich or poor according to the degree in which he can afford to enjoy the necessaries, conveniencies, and amusements of human life. But after the division of labour has once thoroughly taken place, it is but a very small part of these with which a man's own labour can supply him. The far greater part of them he must derive from the labour of other people, and he must be rich or poor according to the quantity of that labour which he can command, or which he can afford to purchase."

Adam Smith pointed out the dangers of a system that allowed individuals to pursue individual self-interest at the deteriment of the rest of society. He warned against the establishment of monopolies. "A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly understocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate."

Smith went onto argue: "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary."

Smith argued that capitalism results in inequality. For example, he wrote about the impact poverty had on the lives of the labouring class: "It is not uncommon... in the Highlands of Scotland for a mother who has borne twenty children not to have two alive... In some places one half the children born die before they are four years of age; in many places before they are seven; and in almost all places before they are nine or ten. This great mortality, however, will every where be found chiefly among the children of the common people, who cannot afford to tend them with the same care as those of better station."

To protect the poor Smith argued for government intervention: ""The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life... But in every improved and civilized society this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it."

In the Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations Smith argues that progressive taxation is a vital ingredient in the creation of a fair society: "The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. The expense of government to the individuals of a great nation is like the expense of management to the joint tenants of a great estate, who are all obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective interests in the estate. In the observation or neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality or inequality of taxation.

It has been wrongly argued that Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations was the world's first book on economics. In fact, Anders Chydenius, a Swedish priest and economist published The National Gain in 1765. Although both men covered similar ground, Smith's book changed the way people approached the subject of economics.

In 1777 he was appointed commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother in Edinburgh. In 1787 he was elected lord rector of Glasgow University.

Adam Smith died in Edinburgh on 17th July, 1790.

On this day in 1829 Bessie Rayner Parkes, the daughter of the solicitor, Joseph Parkes, was born on 16th June 1829. Her grandfather was Joseph Priestley, the scientist and political reformer who was forced to leave the country in 1774. Bessie's father was also a Unitarian with radical political views and was a close friend of reformers such as Henry Brougham and John Stuart Mill.

In 1846 Parkes met Barbara Bodichon, who was running a progressive school in London. The two women became close friends and over the next few years wrote several pamphlets on women's rights, including Remarks on the Education of Girls (1856).

Parkes and Bodichon felt that there was a need for a journal for educated women and in 1858 they founded The Englishwoman's Review. Parkes became editor and over the next few years she made the journal available to writers campaigning for women doctors and the extension of opportunities for women in higher education.

Parkes continued to publish pamphlets and in Essays on Women's Work (1866) she argued that the laws of the country were based on the assumption that women were supported by their husbands or fathers, but with a shortage of men in the country, this was becoming less likely to happen. Parkes therefore suggested that it was necessary to improve the standard of education for girls.

In 1866 Parkes joined with Barbara Bodichon to form the first ever Women's Suffrage Committee. This group organised the women's suffrage petition, which John Stuart Mill presented to the House of Commons on their behalf.

On a visit to France in 1867, Parkes met Louis Belloc. The couple fell in love and decided to marry. Both families objected to the couple getting married. Belloc was younger than Parkes and had been an invalid for thirteen years. Barbara Bodichon also advised against the relationship but the marriage went ahead.

After Louis Belloc died of sunstroke in 1872, Bessie returned to London with her two children. Belloc had abandoned her Unitarian beliefs and was now a member of the Roman Catholic Church. She was also no longer interested in women's rights. Her daughter, the successful novelist, Marie Belloc-Lowndes, showed little interest in the suffrage movement, and her son, Hilaire Belloc, was one of Britain's leading anti-feminists, being opposed to both women having the vote or experiencing higher education.

Bessie Rayner Belloc died on 23rd March 1925.

On this day in 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands. When supporters of parliamentary reform held a convention the following year, Lovett was chosen as the leader of the group that were now known as the Chartists.

R. G. Gammage, the author of History of the Chartist Movement (1855) later recalled: "This gentleman (Lovett) was a native of Cornwall, and sprang from the poorest class. Lovett was secretary to the Association, and, without exaggeration, it may be affirmed that he was the life and soul of that body. Possessed of a clear and masterly intellect and great powers of application, everything that he attempted was certain of accomplishment; and, though not by any means an orator, he was in matters of business more useful to the movement than those who were gifted with finer powers of speech."

On this day in 1908 Vera Atkins (Vera May Rosenberg) in Bucharest, Romania. Her father, Max Rosenberg and his wife, Zefra Hilda, were both Jewish. The family moved to England in 1933 but after a couple of years returned to mainland Europe to study modern languages at the Sorbonne.

Atkins returned to England when France was invaded by the German Army in May 1940. She joined the French section of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in February 1941, and served as assistant to Maurice Buckmaster, the head of the French Section.

Her work at the SOE included interviewing recruits, organizing their training and planning the reception in France. One of her major tasks was to create cover stories for all the special agents who were about to be sent into territory occupied by Nazi Germany. During the Second World War she sent 470 agents into France including 39 women.

After the war Atkins spent a year interrogating German officials and guards who worked at the concentration camps to discover what had happened to the 118 special agents that had not returned to Britain. This included Yolande Beekman, Andrée Borrel, Madeleine Damerment, Vera Leigh, Gilbert Norman, Sonya Olschanezky, Eliane Plewman, Diana Rowden, Francis Suttill and Violette Szabo,

Atkins, who retired to Winchelsea, Sussex, never wrote her memoirs but gave numerous interviews to those writing about the history of the Special Operations Executive.

Vera Atkins died on 24th June, 2000.

On this day in 1909 Patricia Woodlock, the Women's Social & Political Union organiser in Liverpool, is released from prison. Woodlock was greeted by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and several hundred supporters: "As early as half-past seven a large crowd assembled opposite the prison gates, augmented from time to time by the curious or sympathetic among the passers-by, and time went on the numbers swelled, until several hundreds were waiting, the enlivening strains of Bryer's band and the vigorous efforts of bill-distributors making the time pass quickly. As the hour of release drew near a hush fell on the assembled crowd, and when the gate opened and a solitary figure emerged, a mighty cheer went up. Miss Woodlock, who looked pale and thin, but had the light of indomitable courage burning in her eyes, at once entered Mrs Pethick Lawrence's motor-car, which was in waiting, and was driven away, the crowd following, cheering and singing the Marseillaise. It was inspiriting to see the numbers of strangers – principally girls and working men – joining in the song and waving aloft their tool-bags and dinner-bundles."

Woodlock was taken to the Inns of Court where Emmeline Pankhurst gave a speech acknowledging her commitment to the cause: "Mrs Pankhurst... said, no woman had deserved more highly than this brave pioneer in the cause of woman's freedom… During the time she had been a member of the Union, Patricia Woodlock had over and over again taken a front place in the fighting line, and had proved her devotion to the cause by being five times arrested and four times imprisoned… Patricia Woodlock, whose courage in sustaining prison treatment had fired then with enthusiasm."

Mary Gawthorpe also addressed the meeting: "The women of the country honoured Patricia Woodlock because they loved and honoured the case so much, and because to every woman there always came a day when she realised how infinitely more great the cause itself was than any personal sacrifice that might be made for it." Woodlock replied that it "was the object of the Government in sending women to prison in this so-called century of progress. She supposed that the object of men in political power was to stop women for agitating, but they did not know women, and the more they sent them to prison the more determined the women were when they came out.... When women were determination to have their rights, they would get them. They were not asking for favours because they were women; all they wanted was equality as subject."

On this day in 1917 publisher Katharine Graham was born in New York City. She was a daughter of Agnes Ernst Meyer and Eugene Meyer, who purchased the Washington Post at a bankruptcy sale in 1933.

Katharine was educated at Vassar and the University of Chicago. After graduating in 1938 she worked as a reporter for the San Francisco News. In 1940 she married Philip Graham. The couple had four children: Elizabeth, Donald, William and Stephen. Katharine Graham joined the staff of the Washington Post, where she worked in the editorial and circulation departments.

In 1946 Eugene appointed Katharine's husband as associate publisher. He eventually took over business side of the newspaper's operations. He also played an important role in the paper's editorial policy. It is claimed that Philip Graham had close links with the Central Intelligence Agency and it has been argued that he played an important role in Operation Mockingbird, the CIA program to infiltrate domestic American media. According to Katherine, her husband worked overtime at the Washington Post during the Bay of Pigs operation to protect the reputations of his friends who had organized the ill-fated venture.

As president of the Washington Post Company he purchased radio and television stations WTOP (Washington) and WJXT (Jacksonville). In 1961 Graham purchased Newsweek. The following year he took control of America's two leading art magazines, Art News and Portfolio.

Philip Graham committed suicide by killing himself with a shotgun on 3rd August, 1963. Katharine now took over the running of the newspaper. She held several different posts including president (1963-1973), publisher (1969-1979), chairman of the board (1973-1991) and chairman of the executive committee (1993-2001).

Graham also served as co-chairman of the International Herald Tribune, vice chairman of the board of the Urban Institute and was a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Overseas Development Council. She also wrote Personal History, for which she received the 1998 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Katharine Graham died on 17th July, 2001.

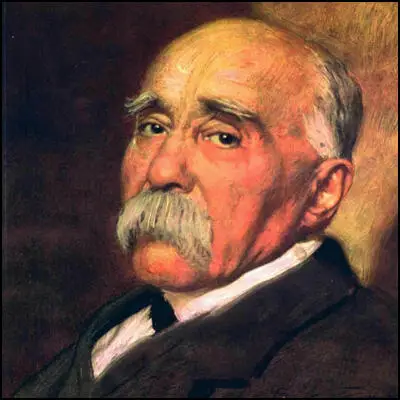

On this day in 1919 Georges Clemenceau makes speech at the Paris Peace Conference.

In the view of the Allied and Associated Powers the war which began on August 1st, 1914, was the greatest crime against humanity and the freedom of peoples that any nation, calling itself civilised, has ever consciously committed. For many years the rulers of Germany, true to the Prussian tradition, strove for a position of dominance in Europe. They were not satisfied with that growing prosperity and influence to which Germany was entitled, and which all other nations were willing to accord her, in the society of free and equal peoples. They required that they should be able to dictate and tyrannise to a subservient Europe, as they dictated and tyrannised over a subservient Germany. Germany's responsibility, however, is not confined to having planned and started the war. She is no less responsible for the savage and inhuman manner in which it was conducted.

Though Germany was herself a guarantor of Belgium, the rulers of Germany violated, after a solemn promise to respect it, the neutrality of this unoffending people. Not content with this, they deliberately carried out a series of promiscuous shootings and burnings with the sole object of terrifying the inhabitants into submission by the very frightfulness of their action. They were the first to use poisonous gas, notwithstanding the appalling suffering it entailed. They began the bombing and long distance shelling of towns for no military object, but solely for the purpose of reducing the morale of their opponents by striking at their women and children. They commenced the submarine campaign with its piratical challenge to international law, and its destruction of great numbers of innocent passengers and sailors, in mid ocean, far from succour, at the mercy of the winds and the waves, and the yet more ruthless submarine crews. They drove thousands of men and women and children with brutal savagery into slavery in foreign lands. They allowed barbarities to be practised against their prisoners of war from which the most uncivilised people would have recoiled.

The conduct of Germany is almost unexampled in human history. The terrible responsibility which lies at her doors can be seen in the fact that not less than seven million dead lie buried in Europe, while more than twenty million others carry upon them the evidence of wounds and sufferings, because Germany saw fit to gratify her lust for tyranny by resort to war.

The Allied and Associated Powers believe that they will be false to those who have given their all to save the freedom of the world if they consent to treat this war on any other basis than as a crime against humanity.

Justice, therefore, is the only possible basis for the settlement of the accounts of this terrible war. Justice is what the German Delegation asks for and says that Germany had been promised. Justice is what Germany shall have. But it must be justice for all. There must be justice for the dead and wounded and for those who have been orphaned and bereaved that Europe might be freed from Prussian despotism. There must be justice for the peoples who now stagger under war debts which exceed £30,000,000,000 that liberty might be saved. There must be justice for those millions whose homes and land, ships and property German savagery has spoliated and destroyed.

That is why the Allied and Associated Powers have insisted as a cardinal feature of the Treaty that Germany must undertake to make reparation to the very uttermost of her power; for reparation for wrongs inflicted is of the essence of justice. That is why they insist that those individuals who are most clearly responsible for German aggression and for those acts of barbarism and inhumanity which have disgraced the German conduct of the war, must be handed over to a justice which has not been meted out to them at home. That, too, is why Germany must submit for a few years to certain special disabilities and arrangements. Germany has ruined the industries, the mines and the machinery of neighbouring countries, not during battle, but with the deliberate and calculated purpose of enabling her industries to seize their markets before their industries could recover from the devastation thus wantonly inflicted upon them. Germany has despoiled her neighbours of everything she could make use of or carry away. Germany has destroyed the shipping of all nations on the high sea, where there was no chance of rescue for their passengers and crews. It is only justice that restitution should be made and that these wronged peoples should be safeguarded for a time from the competition of a nation whose industries are intact and have even been fortified by machinery stolen from occupied territories.

On this day in 1941 an agent cabled NKVD headquarters that intelligence from the networks indicated that "all of the military training by Germany in preparation for its attack on the Soviet Union is complete, and the strike may be expected at any time.". Later Soviet historians counted over a hundred intelligence warnings of preparations for the German attack forwarded to Joseph Stalin between 1st January and 21st June. Many of them came from Richard Sorge. Others came from military intelligence. Stalin's response to an NKVD report from Schulze-Boysen was "this is not from a source but a disinformer."

Sam E. Woods, commercial attaché in Berlin, developed excellent contacts in the German army command - contacts which brought him close to high-ranking German staff officers opposed to Hitler who knew of the plans for Operation Barbarossa. Woods was able to follow the German preparations from July 1940 until the plans were finalized that December. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, agreed that Moscow should be told. Roosevelt ordered, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles met on 20th March, 1940 with the Soviet Ambassador to Washington, Konstantin A. Umansky, to pass along a warning.

On this day in 1944 Marc Bloch was executed. Marc Bloch was born in Lyons, France in 1886. He studied history in Paris, Leipzig and Berlin. After graduating he taught at Montpellier and Amiens. Bloch served as an infantry soldier in the First World War and won four citations and the Legion d'Honneur.

In 1919 Bloch became Professor of Medieval History at Strasbourg University. In 1929 Bloch and Lucien Febvre founded the influential journal, the Annales d'histoire economique et sociale. In a series of articles he emphasized the importance of economic structures and systems of belief in history.

Most of Bloch's research concerned medieval history and the relationship between freedom and servitude. Books by him included Kings and Serfs (1920), Magic Working Kings (1924) and Original Characteristics of French Rural History (1931).

In 1936 Bloch became Professor of Economic History at the Sorbonne. In his book Feudal Society (1939) Bloch described the legal institutions of feudalism.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Bloch joined the French Army. A book on his experiences, Strange Defeat, was published after the war. When Henri-Philippe Petain signed an armistice with Germany Bloch knew that as a Jew he would be a target for the Gestapo. Bloch tried but failed to get his family to the United States.

Bloch now joined the French Resistance and by 1942 he was one of the leaders of the Francs-Tireur group. Bloch was captured by the Germans on 16th June 1944, and after being interrogated and tortured was executed with 27 other members of the resistance in a field outside Lyons. Books published after his death include The Historian's Craft.

On this day in 1953 Margaret Bondfield died at Verecroft Nursing Home, Sanderstead. Margaret Bondfield, the daughter of William Bondfield and Anne Taylor, was born in Chard, Somerset on 17th March 1873. Margaret was Anne's eleventh child and her husband was at that time was sixty-one years old. William Bondfield had worked in the textile industry since he was a young boy and was well known in the area for his radical political beliefs. Philip Williamson has argued: "Her parents gave her a nonconformist faith and ethic, a strong sense of the dignity of work, and a belief in an active female role, while contact with philanthropists and preachers encouraged her to read widely about social, ethical, and spiritual issues."

At the age of fourteen Margaret left home to serve an apprenticeship in a large draper's shop in Hove. She later recalled: "When I first went to Brighton for a holiday in 1887 I had the chance of a job as apprentice to Mrs. White of Church Road, Hove, a friend of my sister Annie. I eagerly grasped this opportunity of earning my living. I did not see my home again for five years. Mrs. White successfully ran one of those old-fashioned businesses where the relations between the customer and assistant were of the most courteous and friendly, and the assistants, of whom I was the youngest, were treated like members of the family."

Margaret Bondfield became friendly with one of her customers, Louisa Martindale, a strong advocate of women's rights. Margaret was a regular visitor to the Martindale home where she met other radicals living in Brighton. Louisa Martindale lent Margaret books and was an important influence on her political development.

In 1894 Margaret went to live with her brother Frank in London. Margaret found work in a shop and after a short period was elected to the Shop Assistants Union District Council. In 1896 Clementina Black of the Women's Industrial Council asked Bondfield to carry out an investigation into the pay and conditions of shop workers. Bondfield's report was published in 1898, the same year she was appointed assistant secretary of the Shop Assistants' Union.

As a result of her work for the Women's Industrial Council, Bondfield became known as Britain's leading expert on shop workers and gave evidence to the Select Committee on Shops (1902) and the Select Committee on the Truck System (1907). During this period she met Mary Macarthur: "I saw a thin white face and glowing eyes, and then I was enveloped by her ardent, young hero-worshipping personality. She was gloriously young and self-confident It was a dazzling experience for a humdrum official to find herself treated with the reverence due to an oracle by one whose brilliant gifts and vital energy were even then manifest." As a Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) executive member, she recommended Macarthur as organizer and in 1906 they established the first women's general union, the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW).

Margaret Bondfield made the decision to concentrate on her career. In her autobiography, A Life's Work (1948): "I concentrated on my job. This concentration was undisturbed by love affairs. I had seen too much - too early - to have the least desire to join in the pitiful scramble of my workmates. The very surroundings of shop life accentuated the desire of most shop girls to get married. Long hours of work and the living-in system deprived them of the normal companionship of men in their leisure hours, and the wonder is that so many of the women continued to be good and kind, and self-respecting, without the incentive of a great cause, or of any interest outside their job... I had no vocation for wifehood or motherhood, but an urge to serve the Union".

Bondfield was chairperson of the Adult Suffrage Society. In 1906 she made a speech where she said: "I work for Adult Suffrage because I believe it is the quickest way to establish a real sex-equality... I have always said in my speeches and in conversation that these women who believe in the same terms as men Bill have a perfect right to go on working for that Bill, and I say good luck to them and may they get it! But don't let them come and tell me that they are working for my class."

Unlike some members of the NUWSS and the WSPU, Bondfield was totally opposed to the idea that initially only certain categories of women should be given the vote. Bondfield believed that a limited franchise would disadvantage the working class and feared that it might act as a barrier against the granting of adult suffrage. This made Bondfield unpopular with middle class suffragettes who saw limited suffrage as an important step in the struggle to win the vote.

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) described a debate she had with Isabella Ford over the issue of women's suffrage: The young Margaret Bondfield tore to shreds the argument that a limited women's franchise was the way forward. Industrial organisation would improve women's lot much more efficiently than votes, she said. If women were to have the vote at all, they should have it as part of a much more radical move towards universal suffrage for both men and women." Sylvia Pankhurst did not agree with this assessment: "Miss Bondfield appeared in pink, dark and dark-eyed with a deep, throaty voice which many found beautiful. She was very charming and vivacious and eager to score all the points that her youth and prettiness would win for her against the plain middle-aged woman with red face and turban hat... Miss Bondfield deprecated votes for women as the hobby of disappointed old maids whom no-one had wanted to marry."

In 1908 Bondfield resigned from the Shop Assistants' Union and became secretary of the Women's Labour League. Bondfield was also active in the Women's Co-operative Guild which was campaigning for minimum wage legislation, an improvement in child welfare and action to lower the infant mortality rate. Her biographer, Mary Agnes Hamilton, commented that "any deficiences... are offset by her personal charm."

In 1910 the Liberal Government asked Bondfield to serve as a member of its Advisory Committee on the Health Insurance Bill. Bondfield's efforts were rewarded when she persuaded the government to include maternity benefits. Bondfield also influenced their decision to make the benefit the property of the mother.

Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett announced that the NUWSS was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Bondfield disagreed with the position that the NUWSS and WSPU took during the First World War. She joined forces with the Women's Freedom League to establish the Women's Peace Crusade, an organization that called for a negotiated peace. Other members included Charlotte Despard, Selina Cooper, Margaret Bondfield, Ethel Snowden, Katherine Glasier, Helen Crawfurd, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Mary Barbour.

In October 1916 Bondfield joined with George Lansbury and Mary Macarthur to set-up a new National Council for Adult Suffrage. The main plan was to persuade the government to reconsider its plans for a limited extension of the franchise. At the time, the Manchester Guardian commented: " She is a little woman but her pleasantly toned, deep voice has great carrying power. I have often seen her sway an audience and lift it for the moment to the height of some great idea by the force of her own feeling and deep sincerity."

In 1923 Margaret Bondfield became one of the first women to enter the House of Commons when she was elected as Labour MP for Northampton. When Ramsay McDonald became Prime Minister in 1924 he appointed Bondfield as parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Labour. One political commentator described her as: "Small in stature with dark hair, wide brows, and bright dark eyes, she reminded her hearers of a courageous robin as, in her clear, resonant, musical voice she told them that the unions must get together for political action if they were to achieve their larger aims."

Margaret Bondfield welcomed the passing of the 1928 Equal Franchise Act. She commented in the House of Commons: "Since I have been able to vote at all I have never felt the same enthusiasm because the vote was the consequence of possessing property rather than the consequence of being a human being... At last we are established on that equitable footing because we are human beings and part of society as a whole."

When Ramsay McDonald became Prime Minister for a second time in 1929 he appointed Bondfield as his new Minister of Labour. Bondfield therefore became the first woman in history to gain a place in the British Cabinet. In the financial crisis of 1931, Bondfield upset many members of the Labour Party when she supported the government policy of depriving some married women of their unemployment benefit. However, she refused to join McDonald's National Government and lost her seat in the 1931 General Election.

As Fran Abrams has pointed out, this brought an end to her career in the House of Commons: "Her seat lost and her parliamentary career at an end, Margaret suffered a complete breakdown. She was ordered to bed with fibrositis - generalised muscle pain - for which she underwent painful treatment, but it was clear she was in poor emotional as well as physical shape. After a long rest she spent several months touring the US before returning to fight Wallsend again in 1935 without success. She was then adopted as Labour candidate for Reading, but she gave up her candidature when it became clear the election would be long delayed by the Second World War."

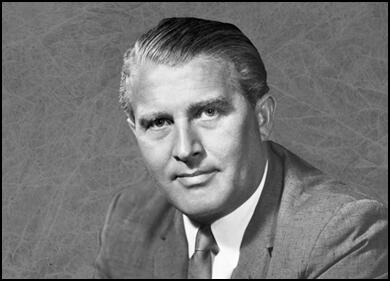

On this day in 1977 Wernher von Braun died. Wernher von Braun, the son of a Prussian baron, was born in Wirsitz, Germany in 1912. He studied engineering at Berlin's Charlottenburg Institute of Technology and after reading The Rocket into Interplanetary Space by Hermann Oberth, he became interested in rocket technology and helped form the German Society for Space Travel.

In 1932 Braun's achievements attracted the attentions of Walter Dornberger, who was in charge of the solid-fuel rocket research and development in the Ordnance Department of the German Army. Dornberger recruited Braun and in 1934 he successfully built two rockets that rose vertically for more the than 2.4 kilometres (1.5 miles).

Dornberger was appointed military commander of rocket research station at Peenemunde in 1937. Braun became technical director of the establishment and he began to develop the long-range ballistic missile, the A4 and the supersonic anti-aircraft missile Wasserfall.

During the Second World War Braun began working on a new secret weapon, the V2 Rocket. This 45 feet long, liquid-fuelled rocket carried a one ton warhead, and was capable of supersonic speed and could fly at an altitude of over 50 miles. As a result it could not be effectively stopped once launched.

Heinrich Himmler saw the military potential of Braun's research and took over control of the research station. Himmler became increasingly concerned about the motivation of Braun, considering him more interested in space travel than developing bombs. In March, 1944, Braun was arrested by the Gestapo and was only released when they became convinced that Braun was willing to use all his energies to develop this bomb that Himmler believed had the potential to win the war.

The V2 Rocket was first used in September, 1944. Over 5,000 V-2s were fired on Britain. However, only 1,100 reached their target. These rockets killed 2,724 people and badly injured 6,000. After the D-Day landings, Allied troops were on mainland Europe and they were able to capture the launch sites and by March, 1945, the attacks came to an end.

With the Red Army advancing on the Peenemunde Research Station, Braun and his staff fled west and surrendered to the US Army. Braun and 40 other rocker scientists were taken to the United States where they worked on the development of nuclear missiles.

In 1952 Braun became technical director of the US Army's Ballistic Missile Agency at Huntsville, Alabama and was chiefly responsible for the manufacture and successful launching of Redstone, Jupiter-C, Juno and Pershing missiles.

After the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik on 4th October, 1957, Braun concentrated on the development of space rockets and in January, 1958 launched Explorer I.

In 1960 Braun became director of the Marshall Space Flight Center where he developed the Saturn rocket that helped the United States to land on the moon in 1969.

When President Richard Nixon dramatically reduced the space budget in 1972 Braun resigned and became vice-president of Fairchild Industries, an aerospace company

Wernher von Braun, who wrote the books Conquest of the Moon (1953) and Space Frontier (1967) died of cancer at Alexandria on 16th June, 1977.