On this day on 7th September

On this day in 1533 Elizabeth, the only child of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn was born. Henry expected a son and selected the names of Edward and Henry. While Henry was furious about having another daughter, the supporters of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon were delighted and claimed that it proved God was punishing Henry for his illegal marriage to Anne.

Retha M. Warnicke, the author of The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn (1989) has pointed out: "As the king's only legitimate child, Elizabeth was, until the birth of a prince, his heir and was to be treated with all the respect that a female of her rank deserved. Regardless of her child's sex, the queen's safe delivery could still be used to argue that God had blessed the marriage. Everything that was proper was done to herald the infant's arrival."

Although Anne Boleyn visited her daughter, for most of the time she was cared for by a large staff. Lady Margaret Bryan was Lady Mistress (the governess with day-to-day control of the nursery). Lady Margaret had also cared for Princess Mary, Elizabeth's elder half-sister. Elizabeth's earliest portraits suggest that she resembled her father in the shape of her face and her auburn hair, but had inherited her mother's coal-black eyes.

The 17-year-old Mary was declared illegitimate, lost her rank and status as a princess and was exiled from Court. She was placed with Sir John Shelton and his wife, Mary Shelton. It has been claimed that "Mary was bullied unmercifully by the Sheltons, humiliated, and was constantly afraid that she would be imprisoned or executed." Alison Plowden has concluded that the treatment Mary received "turned a gentle, affectionate child into a bigoted, neurotic and bitterly unhappy woman."

Catherine of Aragon died on 7th January, 1536. Ambassador Eustace Chapuys reported to King Charles V: "The King dressed entirely in yellow from head to foot, with the single exception of a white feather in his cap. His bastard daughter Elizabeth was triumphantly taken to church to the sounds of trumpets and with great display. Then, after dinner, the King went to the Hall where the Ladies were dancing, and there made great demonstrations of joy, and at last went to his own apartments, took the little bastard in his arms, and began to show her first to one, then to another, and did the same on the following days."

Henry VIII continued to try to produce a male heir. Anne Boleyn had two miscarriages and was pregnant again when she discovered Jane Seymour sitting on her husband's lap. Anne "burst into furious denunciation; the rage brought on a premature labour and was delivered of a dead boy." It has been claimed that the baby was born deformed and that the child was not Henry's. In April 1536, a Flemish musician in Anne's service named Mark Smeaton was arrested. He initially denied being the Queen's lover but later confessed, perhaps tortured or promised freedom. Another courtier, Henry Norris, was arrested on 1st May. Sir Francis Weston was arrested two days later on the same charge, as was William Brereton, a Groom of the King's Privy Chamber. Anne's brother, George Boleyn was also arrested and charged with incest.

Anne was taken to the Tower of London on 2nd May, 1536. Four of the accused men were tried in Westminster ten days later. Smeaton pleaded guilty but Weston, Brereton, and Norris maintained their innocence Three days later, Anne and George Boleyn were tried separately. She was accused of enticing five men to have illicit relations with her. (10) Adultery committed by a queen was considered to be an act of high treason because it had implications for the succession to the throne. All were found guilty and condemned to death. The men were executed on 17th May.

Anne went to the scaffold at Tower Green on 19th May, 1536. The Lieutenant of the Tower reported her as alternately weeping and laughing. The Lieutenant assured her she would feel no pain, and she accepted his assurance. "I have a little neck," she said, and putting her hand round it, she shrieked with laughter. The "hangman of Calais" had been brought from France at a cost of £24 since he was a expert with a sword. This was a favour to the victim since a sword was usually more efficient than "an axe that could sometimes mean a hideously long-drawn-out affair."

Anne Boyleyn's last words were: "Good Christian people... according to the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it... I pray God save the King, and send him long to reign over you... for to me he was always a good, a gentle, and sovereign Lord."

When her mother was executed Elizabeth was only three years old. Patrick Collinson has argued: "Elizabeth can have had few memories of her mother... There is no profit in speculating about the psychological damage which Anne's terrible end might have had on her daughter, although many of Elizabeth's biographers have found significance in the fact that she never in adult life invoked or otherwise referred to her mother."

Shortly after Anne was executed Archbishop Thomas Cranmer annulled her marriage to Henry VIII. A second Act of Succession, passed in June, excluded Elizabeth, like Mary before her, from the succession. However, Henry did not disown Elizabeth, and she received a good education. Richard Fetherston was hired as her tutor. "Elizabeth, like her sister before her, was to benefit from as good an education as the sixteenth century could provide."

On this day in political activist 1833 Hannah More died, aged eighty-eight. She left over £30,000, most of which she bequeathed to charities and religious societies. Linda Colley has argued that "More had become the first British woman ever to make a fortune with her pen."

Hannah More, the fourth of the five daughters of Jacob More (1700–1783) and Mary Grace, was born on 2nd February 1745 at Fishponds, a couple of miles north of Bristol. Her father was a schoolmaster at the local school.

Her biographer, S. J. Skedd, has pointed out: "Hannah More grew up in a loving, intellectual, and predominately female environment. A precocious child and the acknowledged genius of the family, she displayed a quick-witted cleverness and passion for learning which were nurtured not only by her scholarly father, who taught her Latin and mathematics, but also by her mother and sisters."

Jacob More started his own boarding-school at 6 Trinity Street in Bristol. Hannah and her sisters attended the school. She also attended classes at the Bristol Baptist Academy. Later she taught at her father's school. In her late teens Hannah More composed her first significant work, a pastoral verse drama for schoolgirls entitled The Search after Happiness (1762) where she expressed her views on women's education.

In 1767 More accepted a proposal of marriage from William Turner, of Belmont House, Wraxall. Turner, who was twenty years her senior, postponed their wedding three times; on the first occasion he allegedly jilted her at the altar. More finally broke off their engagement in 1773. It has been claimed that this decision "triggered a nervous breakdown". Soon afterwards she resolved never to marry, and refused several subsequent proposals, including one from the poet John Langhorne. Turner offered her an annuity to enable her to pursue a literary career. She initially declined but finally accepted a smaller annuity of £200. This money gave her financial security and independence.

More was a regular visitor to London where she met David Garrick, Joshua Reynolds, Samuel Johnson, and Edmund Burke. In September 1774 she helped Burke in his successful campaign to be elected MP for Bristol. Garrick put on her first play, The Inflexible Captive, at the Theatre Royal in Bath in April 1775. This was followed by her second play, Percy, that was performed at Covent Garden in December 1777. It was a great success and she made nearly £600 from the rights to the play. Her third and final play, The Fatal Falsehood, was far less popular and played for only a few nights.

In 1777 More published Essays on Various Subjects, Principally Designed for Young Ladies. The eight essays dealt with topics such as education and religion. She suggested that schools should stress "the intellectual, sentimental, and religious education of girls" and argued that women were "one of the principal hinges on which the great machine of human society turns".

More met Charles Middleton and his wife at his home at Barham Court, Teston. She was later introduced to John Newton, William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp and became in their campaign against the slave-trade. More wrote: "I tell him (Middleton) I hope Teston will be the Runnymede of the Negroes, and that the great charter of African liberty will be there completed." In January 1788, she wrote the poem, Slavery, to help publicize Wilberforce's proposed measures against the trade.

In August 1789 Wilberforce stayed with her at her cottage in Blagdon, and on visiting the nearby village of Cheddar and according to William Roberts, the author of Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More (1834): they were appalled to find "incredible multitudes of poor, plunged in an excess of vice, poverty, and ignorance beyond what one would suppose possible in a civilized and Christian country". As a result of this experience, More rented a house at Cheddar and engaged teachers to instruct the children in reading the Bible and the catechism. The school soon had 300 pupils and over the next ten years the More sisters opened another twelve schools in the area where the main objective was "to train up the lower classes to habits of industry and virtue".

Michael Jordan, the author of The Great Abolition Sham (2005) has pointed out: "More set up local schools in order to equip impoverished pupils with an elementary grasp of reading. This, however, was where her concern for their education effectively ended, because she did not offer her charges the additional skill of writing. To be able to read was to open a door to good ideas and sound morality (most of which was provided by Hannah More through a series of religious pamphlets); writing, on the other hand, was to be discouraged, since it would open the way to rising above one's natural station."

S. J. Skedd has argued: "More was adamant that the poor should not be taught writing, as it would encourage them to be dissatisfied with their lowly situation; over twenty years later she strongly criticized the National Society for teaching their school pupils the three Rs." Skedd goes onto argue that "the sisters also started evening classes for adults, weekday classes for girls to learn how to sew, knit, and spin, and a number of women's friendly societies, where the virtues of cleanliness, decency, and Christian behaviour were inculcated." Later these schools were handed over to Selina Mills, the future wife of Zachary Macaulay.

Richard S. Reddie has suggested that More was greatly influenced by the ideas of William Wilberforce: "More formed a friendship with William Wilberforce and became the living embodiment of his task to reform manners. If Wesley and the Methodists appeared to concentrate their work on the poor, Hannah More focused on the wealthy farmers and landowners, many of whom were known for their penchant for carousing. With the help of local clergy, she encouraged them to to curb their excessive drinking and coarse behaviour in favour of a more sedate, spiritual existence."

The historian, Linda Colley, described Hannah More in her book, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (1992) as "push, humourless and complacent and could be unctuously sycophantic where influential men were concerned, whether they were politicians, peers, ecclesiastics or cultural lions such as Samuel Johnson and David Garrick".

More's campaign against the slave-trade associated her with the French Revolution. She complained to Charles Moss, the Bishop of Bath and Wells: "It has been broadly intimated that I have laboured to spread French principles; and one of my schools is specifically charged with having prayed for the success of the French... I am accused of being the abettor, not only of fanaticism and sedition, but of thieving and prostitution." These charges were untrue as she was a strong opponent of democracy.

Hannah More was concerned about the influence of Tom Paine, whose book, Rights of Man, was circulating in cheap editions, throughout Britain. In 1792 she published Village Politics: Addressed to all the Mechanics, Journeymen, and Day Labourers, in Great Britain (1792). The book attempted to ridicule Paine's political ideas. This was followed by a series of pamphlets on political issues for the lower classes. These were published anonymously as Cheap Repository Tracts (1795–8). The successful banker, Henry Thornton, helped pay for these publications. It has been claimed that within a year these pamphlets sold over 2 million copies. They were mainly bought by the wealthy to distribute to the poor. The success of these publications paved the way for the establishment of the Religious Tract Society.

Hannah More's book, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (1799), was a great success with seven editions being printed in the first year alone. In her book she criticised the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Mary Wollstonecraft. She argued that her belief in female rights, encouraged women to adopt an aggressive independence.

More joined the Clapham Set, a group of evangelical members of the Anglican Church, centered around Henry Venn, rector of Clapham Church in London. This inspired the writing of Practical Piety (1811), Christian Morals (1813) and Character and Practical Writings of St Paul (1815). More also became concerned about the growing influence of William Cobbett and his newspaper, The Political Register. Her attack on Cobbett appeared in The Loyal Subject's Political Creed (1817). Cobbett responded by describing More as an "old bishop in petticoats". In 1820 she wrote: "These turbulent times make one sad. I am sick of that liberty which I used so to prize".

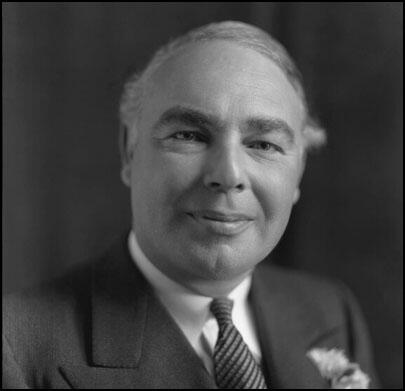

On this day in 1893 Leslie Hore-Belisha was born in Devonport. Educated at Clifton College and Oxford University he served as a major in the British Army during the First World War.

Hore-Belisha, a member of the Liberal Party, worked as a journalist and lawyer before entering the House of Commons for Devonport in 1923.

In 1931 Hore-Belisha supported James Ramsay MacDonald and the National Government and became chairman of the National Liberal Party. MacDonald rewarded Hore-Belisha by appointing him Financial Secretary of the Treasury. In 1934 he became Minister of Transport. He successfully reduced the number of road accidents by introducing Belisha beacons at pedestrian crossings, a new highway code and driving tests for motorists.

In 1937 Neville Chamberlain appointed Hore-Belisha as Secretary of State for War. This was a controversial decision as the former holder of the post, Alfred Duff Cooper, was popular with the British armed forces. Hore-Belisha introduced a series of reforms to improve recruitment. Pay and promotion prospects were improved for all ranks, together with more generous pensions. He also introduced modernised barracks with showers and recreation rooms. Married men over the age of twenty-one were now allowed to live with their families.

Hore-Belisha upset the Army Council by replacing three senior members with younger and more flexible men. He also upset Neville Chamberlain by suggesting the introduction of military conscription during his negotiations with Adolf Hitler in 1938. His attempts to persuade Chamberlain to rapidly increase spending on the armed forces was also unsuccessful.

In the House of Commons the Conservative Party MP Archibald Ramsay was the main critic of having Jews in the government. In 1938 he began a campaign to have Hore-Belisha sacked as Secretary of War. In one speech on 27th April he warned that Hore-Belisha "will lead us to war with our blood-brothers of the Nordic race in order to make way for a Bolshevised Europe."

Hore-Belisha had a poor relationship with General John Gort, Chief of the Imperial General Staff. By the outbreak of the Second World War the two men were not on speaking terms.

In May 1939 Archibald Ramsay founded a secret society called the Right-Club. This was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. In his autobiography The Nameless War Ramsay argued: "The main object of the secret society was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry... Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence." Ramsay continued his campaign against Hore-Belisha and even distributed in Parliament free copies of right-wing magazines that included articles attacking the Secretary of War.

Neville Chamberlain eventually decided to remove Hore-Belisha as Secretary of State for War and appoint him as Minister of Information. Lord Halifax objected, claiming that it was "inappropriate to have a Jew in charge of publicity." In January 1940 Hore-Belisha was sacked as Secretary of State for War.

In 1945 Winston Churchill appointed Hore-Belisha as Minister of National Insurance. However, he lost office when the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election. Leslie Hore-Belisha, who lost his seat in the election, died in 1957.

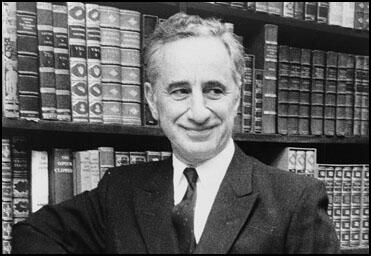

On this day in 1909 Elia Kazan Kazanjoglous) was born in Constantinople, Turkey. Four years later the Kazan family moved to the United States. Kazan attended Williams College in Massachusetts before studying at the Drama School at Yale University.

In 1932 Kazan joined the Group Theatre in New York led by Lee Strasberg. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues. Those involved in the group included John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg and Lee J. Cobb.

Kazan joined the American Communist Party in 1934 and the following year appeared in Waiting for Lefty, a play by a fellow party member, Clifford Odets. Kazen became active in the Actors Equity Association. He worked closely with Philip Loeb, a fellow member of the American Communist Party.

Kazen recalled in his autobiography, Elia Kazan: A Life (1989): "In 1934, when I was in the Party, we helped start a left-wing movement in a very conservative Actors' Equity Association. Our prime goal was to secure rehearsal pay for the working actor and to limit the period when a producer could decide to replace an actor in rehearsal without further financial obligation... I was working on reforming Equity with a fine man named Phil Loeb... Our cause was so just that now, looking back, it's hard to believe there was any opposition to what we were proposing. Still it wasn't an easy to fight to win."

Kazan also appeared as an actor in two movies: City for Conquest (1940) and Blues in the Night (1941). In 1947 Kazan, Lee Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford established the Actors Studio, where they pioneered the idea of Method Acting (a system of training and rehearsal for actors which bases a performance upon inner emotional experience).

Elia Kazan directed All My Sons, a play by a young playwright, Arthur Miller. It opened at the Coronet Theatre on 29th January, 1947, and starred Ed Begley, Karl Malden and Arthur Kennedy. As Michael Ratcliffe pointed out: "A family tale of corrupt profiteering at home that led to the death of US pilots abroad, it exploded in the pause between victory and the attempted press-ganging of show business for Washington's cold war. From this point on, Miller's best scenes display a mastery of conversation, a gift for sketching vivid characters on the margins of a play, and a narrative talent for seizing the spectator's attention from the start." The play won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award and ran for 328 performances.

Miller sent details of his next play, Death Of A Salesman, to Kazan. He thought it was "a great play" and that the character of Willy Loman reminded him of his father. Miller later recalled that Kazan was the "first of a great many men - and women - who would tell me that Willy was their father." The play opened at the Morosco Theatre on 10th February, 1949. It was directed by Kazan and featured Lee J. Cobb (Willy Loman), Mildred Dunnock (Linda), Arthur Kennedy (Biff) and Cameron Mitchell (Happy).

Death Of A Salesman played for 742 performances and won the Tony Award for best play, supporting actor, author, producer and director. It also won the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play. Miller was himself highly critical of the play: "I knew nothing of Brecht then or of any other theory of theatrical distancing: I simply felt that there was too much identification with Willy, too much weeping, and that the play's ironies were being dimmed out by all this empathy."

Kazan also worked with Tennessee Williams on the Pulitzer Prize winning, A Streetcar Named Desire (1947). Kazan also became interested in movies and directed three films that dealt with social issues: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), Gentlemen's Agreement (1947), The Sea of Grass (1947) and Boomerang! (1947).

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

Ten of those named: Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

Kazan was known for his left-wing views and he was eventually called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Controversially, Kazan decided to name eight people who had been fellow members of the American Communist Party in the 1930s. As a result, these people were called before the HUAC. Those that refused to name names, were blacklisted. Kazan later claimed he felt no guilty about what he had done: "There's a normal sadness about hurting friends, but I would rather hurt them a little than hurt myself a lot."

As a reward for his co-operation, Kazan was allowed to continue working in Hollywood. Films included and Pinky (1949), Panic in the Streets (1950), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Viva Zapata! (1952) and Man on a Tightrope (1953).

On the Waterfront (1954), was an attempt to justify the morality of providing information on friends to people in authority. Budd Schulberg, the writer and the actor Lee J. Cobb, who both testified before the HUAC, also worked on the film. Other movies directed by Kazan during this period included East of Eden (1955), Baby Doll (1956) and Splendor in the Grass (1960).

Kazan also wrote several novels including America, America (1962), The Arrangement (1967), The Assassins (1972) and The Understudy (1974). In his autobiography, A Life (1988), Kazan attempted to defend his decision to give names of his former friends to the House of Un-American Activities Committee. One critic has described it as "maybe the best show business autobiography of the century."

Elia Kazan, who was married three times (Molly Thatcher, Barbara Loden and Frances Rudge), died on 28th September, 2003. The film critic, David Thompson, wrote at the time of his death: "There were people who hadn't spoken to him in over 45 years; and who had crossed the street sometimes to avoid him. They had their reasons, good reasons; but everyone has his reasons. And the man is dead now, and his size cannot be denied any longer. Crossing the street will not do. Elia Kazan was a scoundrel, maybe; he was not always reliable company or a nice man. But he was a monumental figure, the greatest magician with actors of his time, a superlative stage director, a film-maker of real glory, a novelist, and finally, a brave, candid, egotistical, self-lacerating and defiant autobiographer - a great, dangerous man, someone his enemies were lucky to have."

On this day in 1910 Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt died. John Everett Millais became friends with William Holman Hunt, a fellow student at the Royal Academy School. They both rejected the ideas of Joshua Reynolds, who argued in his famous Seven Discourses on Art, that young British artists should follow in the Renaissance tradition, to admire the work of Raphael, and to aspire to the classical ideal "that perfect beauty never found in nature but attainable by the artist through careful selection and improvement". Hunt and Millais reacted against this view and in September 1848 they joined up with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Woolner and James Collinson to establish what became known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Other artists such as Charles Allston Collins and Ford Madox Brown were closely associated with the group but were never official members of the PRB.

The Pre-Raphaelites focused on serious and significant subjects and were best known for painting subjects from modern life and literature often using historical costumes. They painted directly from nature itself, as truthfully as possible and with incredible attention to detail. They were inspired by the advice of John Ruskin, the English critic and author of Modern Painters (1843). He had encouraged artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing."

John Everett Millais, who had already developed a reputation as a artist, now tried to put Pre-Raphaelite ideas into practice. His first major painting in the new style was Isabella. According to Malcolm J. Warner: "It shows the use of portraiture as an antidote to idealization, the stiffness of pose intended to recall medieval art, the minute, all-over detail, and the high colour key that characterized early Pre-Raphaelitism."

As Ian Chilvers, the author of Art and Artists (1990) has pointed out: "They (Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) chose religious or other morally uplifting themes and had a desire for fidelity to nature that they expressed through detailed observation of flora, etc., and the use of a clear, bright, sharp-focus technique... When their meaning became known in 1850 the group was subjected to violent criticism and abuse."

The most important attack on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood came from Charles Dickens in his journal Household Words on 15th June, 1850: "You will have the goodness to discharge from your minds all Post-Raphael ideas, all religious aspirations, all elevating thoughts, all tender, awful, sorrowful, ennobling, sacred, graceful, or beautiful associations, and to prepare yourselves, as befits such a subject Pre-Raphaelly considered for the lowest depths of what is mean, odious, repulsive, and revolting."

Dickens then went on to criticize Millias's painting, Christ in the House of His Parents, that had appeared for the first time at the 1850 Royal Academy Exhibition: "You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England. Two almost naked carpenters, master and journeyman, worthy companions of this agreeable female, are working at their trade; a boy, with some small flavor of humanity in him, is entering with a vessel of water; and nobody is paying any attention to a snuffy old woman who seems to have mistaken that shop for the tobacconist’s next door, and to be hopelessly waiting at the counter to be served with half an ounce of her favourite mixture. Wherever it is possible to express ugliness of feature, limb, or attitude, you have it expressed. Such men as the carpenters might be undressed in any hospital where dirty drunkards, in a high state of varicose veins, are received. Their very toes have walked out of Saint Giles’s."

On the 7th May, 1851, The Times accused John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Charles Allston Collins of “addicting themselves to a monkish style”, having a “morbid infatuation” and indulging in “monkish follies”. Finally, the works are dismissed as un-English, “with no real claim to figure in any decent collection of English painting.” Six days later John Ruskin had a letter published in the newspaper, where he came to the defence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In another letter published on 30th May, Ruskin claimed that PRB “may, as they gain experience, lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”.

Ruskin now published a pamphlet entitled, Pre-Raphaelitism (1851). He argued hat the advice he had given in the first volume of Modern Painters had “at last been carried out, to the very letter, by a group of young men who... have been assailed with the most scurrilous abuse... from the public press.” Aoife Leahy has argued: "Ruskin’s defences had now taken a new and decidedly evangelical tone. he had formed friendships with the Pre-Raphaelite artists on the basis of his letters to The Times and, just as significantly, he had been personally harassed by members of the public for his views."

However, most art critics agreed with Dickens rather than Ruskin. As Lucinda Hawksley has pointed out: "Millais... was one of seven young artists, all of whom were Royal Academy trained, who formed a group called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (known as the PRB). They disagreed with many of the principles of art as defined by the rigid government of the Royal Academy and wanted to paint in the style that had been popular in Italy before the advent of Raphael. When the authorities and the public discovered - by an unfortunate chance - what the letters PRB stood for, they were furious at the group's perceived arrogance and actively turned against them, their followers and anyone who assumed a Pre-Raphaelite style of painting. It was several years before artists who painted in this style were accepted back into mainstream galleries. Millais was one of the fortunate few who was not ruined by the furore, largely because he was kept financially secure by family money."

Aoife Leahy has argued that: "The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood itself lost its cohesion as a group in 1853 and no longer held meetings after this date. Ruskin, however, continued for some time to write about these same artists and the movement they had inspired in confident tones, with no note of disharmony. Fortunately, he had generally referred to the Pre-Raphaelites as a school and continued to do so in a seamless fashion. Having begun to defend the P.R.B. at a rather late stage, Ruskin seems to over-compensate by making no mention of the group’s break-up in his critical writings."

On this day in 1916 Ishbel Ross, writes about life in the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit.

What a night we had, we all shivered with cold and had to get up and pace up and down to get warm. We shook hands with a woman soldier in the Serbian Army who came up to the camp to see us. Her name is Milian and she has such a nice face, so sturdy too. She had been fighting for three years and was so pleased to have her photo taken.

in Serbia. Ishbel Ross is the second from the right.

On this day in 1940 300 German bombers and 600 escorting fighters arrived over London. It was the first day of the Blitz. Sector Controllers looked up anxiously, reluctant to commit their planes to battle until the raiders split up to make for their allocated airfield targets. Fighter Command No. 11 under Keith Park did not intercept the bombers in large numbers, thus masking their true strength. An off duty fire officer in Dulwich "saw something that made him jump up and hurriedly struggle into his uniform. The sky was filled with an ever-darkening rash of black dots that he realised were planes in numbers he had never seen before - and they were all making for the East End."

The Luftwaffe was heading for the Royal Victoria Docks and the Surrey Docks that were situated on the U-shaped bend of the Thames round the Isle of Dogs, and was unmistakable from the air. Barbara Nixon, an actress who was a volunteer ARP warden in Finsbury, later recalled that although four miles away she could see that the people in "the East End were getting it... we could see the miniature silver planes circling round and round the target area in such perfect formation that they looked like a children's toy model of flying boats or chair-o-planes at a fair... Presently we saw a white cloud rising; it looked like a huge evening cumulus, but it grew steadily, billowing outwards and always upwards... The cloud grew to such a size that we gasped incredulously; there could not ever in history have been so gigantic a fire."

Cyril Demarne, an officer in the Fire Service, later commented: "Columns of fire pumps, five hundred of them ordered to West Ham alone, sped eastwards to attend fires in ships and warehouses, sugar refineries, soap works, tar distilleries, chemical works, timber stacks, paint and varnish works, the humble little homes of workers and hundreds of other fires that, in peace time, would have made headline news. Two hundred and fifty acres of tall timber sacks blazed out of control in the Surrey Commercial Docks; the rum quay buildings of the West India Docks, alight from end to end, gushed blazing spirit from their doors."

The Fire Service had difficulty in dealing with the large number of fires that had been started by the bombing raid. Calls went out for additional fire engines. Over a thousand were being used in the dock area alone. West Ham Fire Brigade asked for another 500. They came from all over London, and from as far away as Birmingham and Bristol. Over 300 pumps were fighting one blaze. The fire officer at the Surrey Commercial Docks called central officer: "Send all the bloody pumps you've got. The whole bloody world's on fire."

Another major target was the Beckton Gasworks, the largest in Europe, which supplied central London, was badly damaged. Rumours quickly spread that the enveloping sulphurous smell meant that the Germans had dropped mustard-gas canisters. Acrid black smoke came from the bombed warehouse of the Silvertown rubber factory. "Molten tar from another factory flowed across the North Woolwich Road, bogging down fire engines, ambulances and Civil Defence vehicles... An army of rats swarmed from a soap factory in Silvertown. A grain warehouse was on fire too - and when a large quantity of wheat burns, as the fireman found, it leaves a sticky residue that was in danger of pulling off their boots."

An underground shelter in Shoreditch suffered a direct hit and over forty people were killed: "Children sleeping in perambulators and mothers with babies in their arms were killed when a bomb exploded on a crowded shelter in an East London district during Saturday night's raids. By what is described as 'a million-to-one chance' the bomb fell directly on to a ventilator shaft measuring only about three feet by one foot. It was the only vulnerable place in a powerfully protected underground shelter accommodating over 1,000 people. The rest of the roof is well protected by three feet of brickwork, earth, and other defences, but over the ventilator shaft there were only corrugated iron sheets. The bomb fell just as scores of families were settling down in the shelter to sleep there for the night. Three or four roof-support pillars were torn down and about fourteen people were killed and some forty injured. In one family three children were killed, but their parents escaped. Although explosions could be heard in all directions and the scene was illuminated by the glow of the East End fires civil defence workers laboured fearlessly among the wreckage seeking the wounded, carrying them to safer places, and attending to their wounds before the ambulances arrived."

Soon after 6 p.m. the All Clear went, and stunned East Enders emerged from public shelters. They discovered that the Fire Brigade was having terrible difficulty controlling over 40 major fires. Water pipes and gas mains were shattered by explosions and telephone cables were severed. Communication between the fire services and Civil Defence was kept going only by the courage of motor-bike dispatch riders or teenage messenger boys on bikes painted yellow and with a tin hat and an armband to identify them. Driving through tunnels of fire, and dodging unexploded bombs to carry messages from fire crews to control rooms.

Just after 8 p.m., 250 German bombers came back and using the fires below as a marker, dropped 330 tons of high-explosives and 440 incendiary canisters. The docks were the principal target, but many bombs fell on the residential areas around them resulting in 448 Londoners were killed and another 1,600 were seriously injured. The government had miscalculated the effect of the first great air raid on London. The prediction had been there would be many more deaths. However, they under-estimated the number of houses that would be destroyed. It has been claimed that 35 times as many civilians were made homeless as were killed. At precisely 8.07 that evening, as the air bombardment was at its height, the code word "Cromwell" was sent to military units throughout Britain. The code's message was "the German invasion of Britain was about to begin."

On this day in 1953 Nikita Khrushchev is elected first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He immediately arranged for the execution of Lavrenti Beria, head of the Secret Police and gradually he gained control of the party machinery. In 1955 he joined with Nikolai Bulganin to oust Gregory Malenkov from power. He also decided to condemn Joe Stalin's period of rule in the Soviet Union.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He argued: "Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism."

Khrushchev condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. During the speech he suggested that Stalin had ordered the assassination of Sergy Kirov. Later Khrushchev launched an investigation into the assassination of Kirov and other Stalin crimes. However, according to one insider, Feliks Chuev, the Shvernik Commission "found nothing against Stalin" but "Khrushchev refused to publish it - it was of no use to him."

In the summer of 1956 Gregory Malenkov, Nikolai Bulganin, Vyacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich attempted to oust Khrushchev This was unsuccessful and Khrushchev now purged his opponents in the Communist Party. Mikhail Gorbachev was one of those who supported Khrushchev's actions: "Khrushchev's secret speech at the XXth Party Congress caused a political and psychological shock throughout the country. At the Party krai committee I had the opportunity to read the Central Committee information bulletin, which was practically a verbatim report of Khrushchev's words. I fully supported Khrushchev's courageous step. I did not conceal my views and defended them publicly. But I noticed that the reaction of the apparatus to the report was mixed; some people even seemed confused."

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact.

Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. Imre Nagy was imprisoned and executed in 1958.

In 1958 Khrushchev replaced Gregory Malenkov as prime minister and was now the undisputed leader of both state and party. In the Soviet Union he promoted reform of the Soviet system and began to place an emphasis on the production of consumer goods rather than on heavy industry.

Nikita Khrushchev eased censorship in the Soviet Union and allowed One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Alexander Solzhenitsyn to be published. Some pointed out that this was part of his de-Stalinization policy and did not reflect a genuine increase in freedom. His critics pointed out that books such as Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak were still banned.

In 1959 Khrushchev announced a change in foreign policy. In 1959 visited the United States and offered "the capitalist countries peaceful competition". Khrushchev was due to attend the Paris Summit Conference in 1960 when a reconnaissance plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. He cancelled the meeting and later that year at the Union Nations he attacked Western influence in the Congo.

When John F. Kennedy replaced Dwight Eisenhower as president of the United States he was told about the CIA plan to invade Cuba. Kennedy had doubts about the venture but he was afraid he would be seen as soft on communism if he refused permission for it to go ahead. Kennedy's advisers convinced him that Castro was an unpopular leader and that once the invasion started the Cuban people would support the ClA-trained forces.