On this day on 7th December

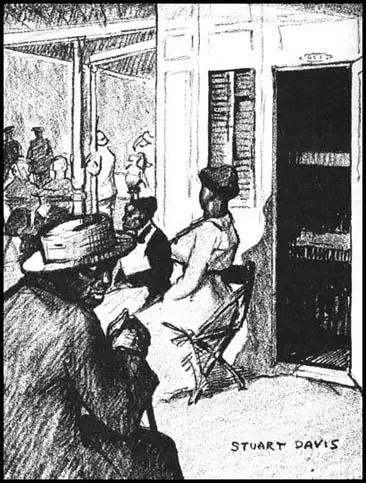

On this day in 1894 artist Stuart Davis was born in Philadelphia. His father was the art editor of the Philadelphia Press. At the age of sixteen Davis began studying at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, leader of what became known as the Ash Can School. Davis developed left-wing views and in 1911 began contributing pictures to the radical journal, The Masses.

Claude McKay has argued: "Some times the magazine (The Masses) repelled me. There was one issue particularly which carried a powerful bloody brutal drawing by Robert Minor. The drawing was of Negroes tortured on crosses deep down in Georgia. I bought the magazine and tore the cover off, but it haunted me for a long time. There were other drawings of Negroes by an artist named Stuart Davis. I thought they were the most superbly sympathetic drawings of Negroes done by an American. And to me they have never been surpassed."

In 1923 Davis moved to New Mexico where he painted still-lifes. He also began experimenting with Cubism but it was only after spending a year in Paris that he developed his own distinctive style. His abstract patterns that included lettering was inspired by advertisement posters.

In 1934 Stuart Davis and Hugo Gellert established the Artists' Congress magazine, Art Front. Davis became its art director. He also painted several public murals including: Men Without Women (1932), Swing Landscape (1938) and History of Communication (1939). Stuart Davis, a strong defender of modern art, died in 1964.

On this day in 1902 cartoonist Thomas Nast died. Nast was born in Landau, Germany, on 27th September, 1840. His father, a musician, had radical political views and found the conservative Bavarian government oppressive. He therefore decided to take his family to the United States.

Nast was raised in New York City and at the age of 15 had his first drawing published by a national magazine. Inspired by the cartoons of John Leech and John Tenniel, in 1855 Nast started working for Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

As soon as Harper's Weekly was launched in 1857, Nast became determined to join the magazine. He had some drawings in the magazine but he did not obtain a full-time post until 1862.

Nast was a staunch opponent of slavery and throughout the Civil War Nast produced patriotic drawings urging people to help crush the rebels. Abraham Lincoln is reported to have said: "Thomas Nast has been our best recruiting sergeant. His emblematic cartoons have never failed to arouse enthusiasm and patriotism."

After the war Nast remained a strong supporter of black civil rights and some of his cartoons attacked Andrew Johnson for undermining Lincoln's policies. During this period Nast began to distort and exaggerate the physical traits of his subjects and therefore played an important role in the development of political caricature.

Thomas Nast also originated the idea in America of using animals to represent political parties. In his cartoons the Democratic Party was a donkey and the Republican Party, an elephant. He also helped to develop the character, Uncle Sam, to represent the United States.

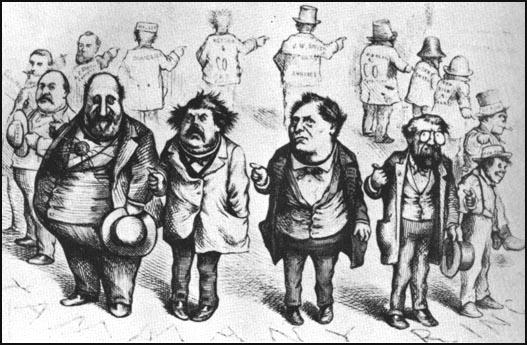

In September 1869, Nast began his campaign in Harper's Weekly against William Tweed, the corrupt political leader of New York City. Pressure was put on Harper Brothers, the company that produced the magazine, and when it refused to sack Nast, the company lost the contract to provide New York schools with books. Nast himself was offered a bribe of $500,000 to end his campaign. This was hundred times the salary of $5,000 that the magazine paid him but Nast still refused and eventually Tweed was arrested and imprisoned for corruption. Nast's campaign against Tweed was later described as "the finest and most effective political cartooning ever done in the United States."

A strong Republican Party supporter, Nast supported Ulysses Grant in 1868 against his rivals, Horace Greeley and Horatio Seymour. Grant's next opponent, Samuel Tilden, had helped Nast remove William Tweed from office. However, Nast continued to use his skill as an artist to undermine Tilden and helped Grant achieve another victory.

Nast also played an important role in securing victory for Rutherhood Hayes in 1876. Afterwards Hayes commented that Nast was "the most powerful single-handed aid we had."

In 1884 Nast changed sides and supported the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland for president. In doing so, he helped Cleveland become the first Democrat president since 1856. After this, Nast was known as the "presidential maker".

In the 1880s Nast's cartoons began to attack trade unions and the Catholic Church. This was less popular with his readers and after a disagreement with the owners of Harper's Weekly, left the journal in 1886. He started his own journal, Nast's Weekly, but it failed and he was left with heavy debts.

Other investments Nast made were also unsuccessful and he got into severe financial difficulties. Nast's cartoon work began to dry up and in 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt helped his old friend by appointing him U.S. consul in Ecuador. This provided him with a steady source of income until his death from yellow fever on 7th December, 1902.

Sweeney, Richard Connolly and Oakley Hall that appeared in Harper's Weekly (19th August, 1871)

On this day in 1914 the Athletic News condemns the government decision to suspend professional football. Cricket and rugby competitions stopped almost immediately after the outbreak of the First World War. However, the Football League continued with the 1914-15 season. Most football players were professionals and were tied to clubs through one-year renewable contracts. Players could only join the armed forces if the clubs agreed to cancel their contracts.

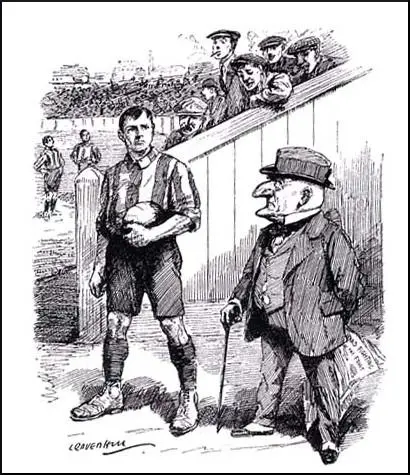

However, in December, 1914 it was announced that the 1915-16 season was cancelled as it was thought that it was hindering Lord Kitchener's recruiting campaign. The Athletic News responded with an attack on the people who ran the Football League: "The whole agitation is nothing less than an attempt by the ruling classes to stop the recreation on one day in the week of the masses ... What do they care for the poor man's sport? The poor are giving their lives for this country in thousands. In many cases they have nothing else ... There are those who could bear arms, but who have to stay at home and work for the army's requirements, and the country's needs. These should, according to a small clique of virulent snobs, be deprived of the one distraction that they have had for over thirty years."

William Joynson Hicks established the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment on 12th December, 1914. This group became known as the Football Battalion. According to Frederick Wall, the secretary of the Football Association, the England international centre-half, Frank Buckley, was the first person to join the Football Battalion. At first, because of the problems with contracts, only amateur players like Vivian Woodward, and Evelyn Lintott were able to sign-up.

but there's only one field today where you can get honour." (21st October, 1914)

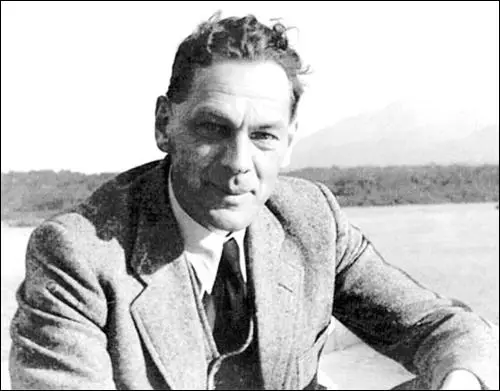

On this day in 1914 Stanley Spencer writes a letter about working for the Royal Army Medical Corps. When he was seventeen he entered the Slade School of Fine Art at University College. Other students at the Slade at that time included Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash, David Bomberg, William Roberts, Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington and Edward Wadsworth.

Spencer's skill as a artist is evident in early works such as The Fairy on the Waterlily Leaf (1910). One of his tutors, Henry Tonks argued that Spencer had the most original mind of any student he had the pleasure of teaching. At the Slade he won the Composition Prize with his painting The Nativity (1912). However, as his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His four years at the Slade were not altogether happy. He was marked out as a misfit by his physical appearance: his diminutiveness (he was only 5 feet 2 inches), his heavy fringe, and pudding-basin haircut. His aura of other-worldliness was enhanced by the fact that he commuted daily by train from Berkshire. He was known jeeringly as Cookham, and terrified by being put upside-down in a sack."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Spencer joined the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He worked at Beaufort Hospital in Bristol where he helped to nurse soldiers wounded on the Western Front. On 7th December 1915 he wrote to his friend, Henry Lamb: "Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night - this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre."

In August 1916 he was sent as part of the 68th Field Ambulance unit to Salonika, a port being defended by General Maurice Sarrail and 150,000, British and French soldiers. In August 1917 he volunteered for the infantry, joining the 7th battalion, the Royal Berkshires, and spending several months in the front line. He later recalled: "Our activities consisted of outpost duty and patrolling the wire at night and during the daytime doing odd fatigues, just outside our dugouts. In the evening just before sunset, the Bulgars started a barrage. The shells dropped uncomfortably near and I was glad when getting into the outposts, we were able to take cover in a communication trench."

On one occasion he went out on patrol with one of the officers: "I went out with a captain and he was hit and sank to the ground. His hand went up to his neck and I saw a gaping bullet wound in it. I bandaged the wound the best I could and called for stretcher-bearers. I helped to support the captain, who was paralyzed." Spencer was devastated when he heard him whisper to another officer: "Understand, Spencer is not a fool; he is a damned good man." Spencer was shocked by what he heard: "What's all this? Who has been saying otherwise?"

In May, 1918, Spencer was asked to contribute to the government's planned Hall of Remembrance. The letter asked him to to paint a picture about his experiences in Salonika. However, it was not until after the Armistice that Spencer painted Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

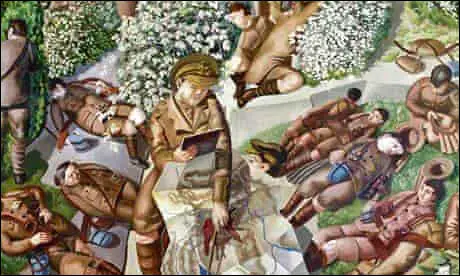

After the war Stanley Spencer was commissioned by Louis and Mary Behrend in memory of Mrs Behrend's brother Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham to paint a decorative mural of army life during the First World War. Sandham had died in 1919 after an illness contracted in in Salonika. The nineteen paintings appeared in the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire. The work was painted as a modern parallel to Giotto's Arena Chapel in Padua. The cycle of scenes from everyday military life culminates in the altarpiece, Resurrection of the Soldiers.

Stanley Spencer painted The Resurrection, between 1924 and 1926 in a studio in Hampstead borrowed from Henry Lamb. When it was showed for the first time in February 1927 The Times critic described it as "the most important picture painted by any English artist in the present century… It is as if a Pre-Raphaelite had shaken hands with a Cubist". The painting was purchased by Joseph Duveen who then gave it to the Tate Gallery.

One critic argued that "Spencer believed that the divine rested in all creation. He saw his home town of Cookham as a paradise in which everything is invested with mystical significance. The local churchyard here becomes the setting for the resurrection of the dead. Christ is enthroned in the church porch, cradling three babies, with God the Father standing behind. Spencer himself appears near the centre, naked, leaning against a grave stone; his fiancée Hilda lies sleeping in a bed of ivy. At the top left, risen souls are transported to Heaven in the pleasure steamers that then ploughed the Thames."

While working on this cycle almost continuously between 1926 and 1932, Spencer lived in a cottage alongside the chapel with his wife, Hilda Carline (1889–1950) and their two daughters: Shirin (b. 1925) and Unity (b. 1930). The cultural historian, Fiona MacCarthy has argued: "The narrative of Stanley Spencer's war - the wounded arriving at Beaufort, the training camp at Tweseldown, the day-to-day routines of service in Macedonia - climaxes in the crowded, joyful central composition The Resurrection of the Soldiers covering the whole east wall. It is a highly personal sequence that transcends the anecdotal, treating the grand themes of glory and redemption in an extraordinary fusion of grandiloquence and homeliness."

After completing the Sandham Memorial Chapel Spencer and his young family moved to Lindworth, a house in Cookham. However, it was not a happy marriage and her passionate Christian Science principles seriously impaired their sex life. During this period Spencer became friendly with Patricia Preece who lived in Cookham with her friend and sexual partner Dorothy Hepworth. Hilda's refusal to accede to demands for a ménage à trois demanded by Spencer forced her eventually to file for a divorce which was granted on 25th May 1937.

Spencer married Preece four days later. They never lived together and according to Tee A. Corinne: "Spencer went into debt giving Preece money, clothing, and jewelry... Spencer then married Preece, but when he attempted to consummate the marriage, Preece immediately fled to Hepworth. Although Spencer and Preece never lived together as man and wife, they never divorced." Although the marriage was unconsummated, it did produce some remarkable nude portraits including Nude: Patricia Preece (1935), Self Portrait with Patricia Preece (1936) and Double Nude Portrait: the Artist and his Second Wife (1937).

Spencer continued to paint pictures of his marriage to Hilda Carline. This included Domestic Scenes: At the Chest of Draws (1936), The Beatitudes of Love (1937) and Romantic Meeting (1938). He also wrote her many letters but following a mental breakdown she was admitted to Banstead Mental Hospital in Epsom. Spencer gave his house in Cookham to Patricia Preece who rented it out in 1938, and he was forced to move to a rented room in Adelaide Road, Hampstead. Over the next few years he produced a series of paintings entitled Christ in the Wilderness (1939–53).

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the War Artists' Advisory Committee commissioned Spencer to record shipbuilding on the River Clyde. As his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, points out: "His work was based at Lithgow's shipyard in Port Glasgow on the Firth of Clyde, concentrated on merchant ships under construction, and Spencer spent extended periods in Scotland during and immediately after the war. Spencer's war work came as a reprieve from his anxious isolation. He was able to immerse himself in the day-to-day activities of ordinary working people, intimately involved in the highly skilled processes of making with which he had always felt an innate sympathy. The Clyde shipbuilding paintings were conceived on an epic scale. Spencer's proposal was for a three-tier frieze 70 feet long. Eight of the projected thirteen canvases had been completed by the time the war artists were disbanded in 1946."

In September 1945 Spencer returned to Cookham, settling in Cliveden View, a small house belonging to his brother Percy Spencer. His former wife, Hilda Carline, died of breast cancer in 1950. He was devastated by the news and "he continued to write her his long, hectic, erotic, often incoherent letters." Over the next few years he completed a new cycle, Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta (1955-1959).

In July 1959 he was knighted by Elizabeth II. His wife, Patricia Preece, now arrived back on the scene and took the title, Lady Spencer. Five months later, on 14 December 1959, Stanley Spencer died of cancer in the Canadian Red Cross Memorial Hospital at Taplow.

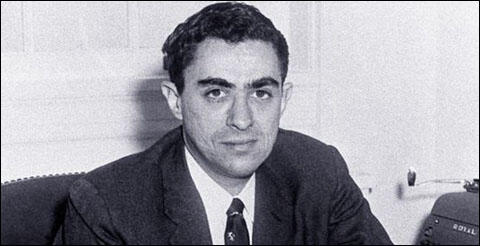

On this day in 1931 historian Richard N. Goodwin was born in Boston. He graduated from Tufts University in 1953. He then went on to study law at Harvard University. Goodwin joined the Massachusetts State bar in 1958. He worked for Felix Frankfurter before being appointed as special counsel to the Legislative Oversight Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1959 John F. Kennedy appointed Goodwin as a member of his speech writing staff. The following year he became Kennedy's assistant special counsel. Goodwin was also a member of Kennedy's Task Force on Latin American Affairs and in 1961, was appointed Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, a position he held until 1963. As one of Kennedy's specialists in Latin-American affairs, Goodwin helped develop the Alliance for Progress, an economic development program for Latin America. Goodwin also served as secretary-general of the International Peace Corps.

After Kennedy's death Goodwin joined the staff of President Lyndon B. Johnson where he worked as a speechwriter and adviser. Goodwin resigned in 1965 over the issue of the Vietnam War and became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut and a visiting professor of public affairs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Goodwin continued to be involved in politics and wrote speeches for presidential candidates Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy. He also wrote for several magazines, including The New Yorker and Rolling Stone. He also published The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys (1986) and Remembering America (1988).

In March, 2001, Goodwin was a member of a United States delegation that visited the scene of the Bay of Pigs battle. The party included Arthur Schlesinger (historian), Robert Reynolds, (the CIA station chief in Miami during the invasion), Jean Kennedy Smith (sister of John F. Kennedy), Alfredo Duran (Bay of Pigs veteran) and Wayne S. Smith (Executive Secretary of his Latin American Task Force).

On this day in 1942 Japan launches attack on United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. The island of Oahu, had been used by the US Navy since the early part of the twentieth century. In April, 1940, the US Fleet had been sent to Pearl Harbor to deter aggressive moves by Japan in the Pacific. The Commander in Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto began planning for a surprise attack on the US Navy at Pearl Harbor early in 1941. Yamamoto feared that he did not have the resources to win a long war against the United States. He therefore advocated a surprise attack that would destroy the US Fleet in one crushing blow. Yamamoto's plan was eventually agreed by the Japanese Imperial Staff in the autumn and the strike force under the command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo sailed from the Kurile Islands on 26th November, 1941.

In the autumn of 1941, Richard Sorge, a Soviet spy based in Japan, provided Joseph Stalin with the information that the Japanese were preparing to make war in the Pacific and were concentrating their main forces in that area in the belief that the Germans would defeat the Red Army. According to Pravda, Sorge informed Soviet intelligence two months before Pearl Harbour "that the Japanese were getting ready for a war in the Pacific and would not attack the Soviet Far East, as the Russians feared."

Military intelligence did intercept two cipher messages from Tokyo to Kichisaburo Normura, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, that suggested an imminent attack, but Captain Richmond Turner, in charge of evaluating and dissemination, did not pass on warnings of the proposed attack to Admiral Husband Kimmel. Later Kimmel testified after the war that had he known of these communications, he would have maintained a much higher level of alert and that the fleet would not have been taken by surprise by the Japanese attack. The historian, Gordon Prange has argued: "If Turner thought a Japanese raid on Hawaii... to be a 50-percent chance, it was his clear duty to say so plainly in his directive to Kimmel."

James Rusbridger, the author of Betrayal at Pearl Harbor (1991) claims that Winston Churchill withheld important information in order to bring the United States into the war: "Churchill was aware that a task force had sailed from northern Japan in late November 1941, and that one of its likely targets was Pearl Harbor... Churchill deliberately kept this vital information from Roosevelt, because he realized an attack of this nature, whether on the U.S. Pacific Fleet or the Philippines, was a means of fulfilling his publicly proclaimed desire to get America into the war at any cost."

The American historian, Joseph E. Persico, has questioned this account: "It must be asked whether drawing the United States into a war with Japan was a logical way for Churchill to get FDR into the war in Europe. Churchill was certainly capable of manipulating intelligence to serve his country's ends. He had no qualms about Stephenson's BSC manufacturing stories to feed to Roosevelt that the Nazis were conspiring to invade South America and threaten the Panama Canal. He allowed Roosevelt to continue thinking that Hitler would invade Britain when his own Ultra interceptions made clear that this danger had passed. However, an attack that would have brought America into a war with the Japanese was a risky bet for Churchill. How he viewed his best interests is clear from a five-page report written on November 12, 1941, less than a month before Pearl Harbor, by the American ambassador to Britain, John Winant. Winant had spent three days with Churchill in the country. According to Winant's notes, forwarded to FDR, Churchill set out three positions in which Britain might find itself. The worst-case scenario, which Churchill considered unthinkable, was that Japan would come into the war against Britain and that America would stay out. The next best outcome would be for neither Japan nor America to enter the war. But Churchill's preference, the PM told Winant, was that 'the United States enter the war without Japan.' With this as his first choice, it hardly seems that Churchill would deliberately enable a Japanese attack on America by withholding intelligence from Roosevelt."

Later, General Hideki Tojo claimed that Japan was acting in self defence: "The main American naval forces were shifted to the Pacific region and an American admiral made a strong declaration to the effect that if war were to break out between Japan and the United States, the Japanese navy could be sunk in a matter of weeks. Further, the British Prime Minister (Churchill) strongly declared his nation's intention to join the fight on the side of the United States within 24 hours should war break out between Japan and the United States. Japan therefore faced considerable military threats as well. Japan attempted to circumvent these dangerous circumstances by diplomatic negotiation, and though Japan heaped concession upon concession, in the hope of finding a solution through mutual compromise, there was no progress because the United States would not retreat from its original position. Finally, in the end, the United States repeated demands that, under the circumstances, Japan could not accept: complete withdrawal of troops from China, repudiation of the Nanking government, withdrawal from the Tripartite Pact (signed by Germany, Italy and Japan on September 27, 1940). At this point, Japan lost all hope of reaching a resolution through diplomatic negotiation."

the information that the Japanese were preparing to make war in the Pacific

On this day in 1942 Agnes Smedley writes a letter about the way black people are treated in the Deep South. Smedley was a left-wing journalist who had reported on human rights violations in foreign countries. Smedley was especially appalled by the Jim Crow laws.

Smedley wrote: "The treatment of Negroes in the south has humiliated and shamed me so deeply that my blood runs cold in my veins. Traveling by bus, with the rain pouring, the driver ordered a dozen Negroes to step back and let two handsome white women aboard first. They came on, then the driver saw they had Negro blood in their veins - perhaps their hair showed it. The driver slapped his leg and bawled with laughter and said to the white passengers: "Now ain't that a joke! I thought they was white and they are N******." The faces of the two women and of all the colored passengers were frozen. Mine froze too. Some of the white passengers broke into a laugh at the joke. I saw a northern white soldier ask a colored soldier to sit down by him and the latter did so; then the bus driver stopped the bus and said: "Stand up. N******!" The colored soldier stood up. The white soldier said: "Aw hell!" and stood up also. But had that white soldier not been in uniform, I don't know what would have happened. Now when I heard this, I should have stood up and killed the driver. But I sat there petrified, sat there like a traitor to the human race. I kept thinking of what Jesus would have done, and knew that he would perhaps have allowed Himself to be killed. I didn't. I didn't do a thing for many reasons: because I was warned a dozen times by white people that if I did anything it would be the colored people who suffered for it. The whole south whispers if the least thing breaks out. In one town in Georgia a fight started in the colored section of the town. So great is the tension that the minute it started, the railway engine on the train began to toot, the air-raid sirens went off as if there was an air raid, police cars and motorcycles roared through the street, and I heard the firing of guns. A street fight starts such a night alarm."

Smedley caused a stir when she gave an interview to the Los Angeles Tribune where she complained "we can't treat men like dogs and expect them to act like men." As a result of this outburst, J. Edgar Hoover instructed FBI agents to investigate her political past. John S. Gibson of Georgia raised the issue of Smedley's comments in the House of Representatives and accused her of being the "author of many books which portray the glory of the Communist Party."

The FBI interviewed Whittaker Chambers in May 1945. Chambers, a former communist spy, claimed wrongly that Smedley was a secret member of the Communist Party of the United States. This was untrue, in fact Smedley had been a strong opponent of the party since the 1920s. As a libertarian socialist she had appalled by the way the party had supported the repressive policies of Joseph Stalin and his communist government in the Soviet Union.

On this day in 1954 Mabel Stobart died.

Mabel Stobart was born on 3rd February 1862. She married and lived in Africa and British Columbia before returning to Britain in 1907.

A supporter of women's suffrage, Stobart believed women would only get the vote when they demonstrated their ability to help defend the country against the feared threat from Germany. Stobart decided to form the Women's Sick and Wounded Convoy Troops, (WSWCT) an organisation that would help soldiers on the field of battle. In 1912 the WSWCT saw service in the Balkan War where they helped the Bulgarian Army.

In 1914 Stobart and Lady Muir McKenzie formed the Women's National Service League. This included women doctors, trained nurses, cooks, interpreters, and all workers essential for the independent working of a hospital of war.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Stobart and a unit of the Women's National Service League to Belgium where she set up a field hospital. Nearly captured by advancing German troops, Stobart returned to England. However, soon afterwards the Belgian Red Cross invited Stobart to establish a hospital in Belgium that was completely staffed by women.

Once the hospital had been established, Stobart went to the Balkan Front, where she served as commissioned major in charge of a hospital column. After the war Stobart wrote about her war experiences in Miracles and Adventures (1935).